Eastern Murman: social aspects of colonization in the materials of expeditions and travel notes of the 2nd half of the 19th - early 20th centuries

Автор: Tereshchenko Elena Yu.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 41, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article discusses several social aspects of the colonization of Eastern Murman (everyday life, daily work, religious beliefs, schooling, leisure). The historiographic analysis made it possible to identify the specifics of the local (everyday) history of the Kola Peninsula colonization. In the works of A.P. Engelhardt, A.G. Slezskinsky, S.Yu. Witte, S.O. Makarov, V.I. Nemirovich-Danchenko, K.K. Sluchevsky, D.N. Ostrovsky, A.K. Engelmeyer, V.I. Manotskov, A.K. Sidensner, N.V. Romanov, “Materials on the statistical study of Murman” and other sources provide facts from personal and family biography, the circumstances of resettlement to the Murmansk coast, living conditions, home furnishings, especially the education and upbringing of children. The descriptions of the migrants’ lifestyle recorded in the materials of expeditions and travel notes allow us to conclude that the colonists’ socio-cultural adaptation in Eastern Murman, the creation of a human habitat, was primarily associated with the development of the institution of the family. In general, the history of colonization is a unique experience in the development of the Arctic - one of the most productive in world history, which is vital for understanding the Russian North’s geography.

Arctic, kola north, eastern murman, colonization

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318372

IDR: 148318372 | УДК: 94(470)”18/19’’(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2020.41.261

Текст научной статьи Eastern Murman: social aspects of colonization in the materials of expeditions and travel notes of the 2nd half of the 19th - early 20th centuries

Great importance has always been attached to studying the experience of the Arctic territories development. Particular attention is drawn to the Murmansk coast, where a colonization project was implemented; as a result of it new settlements were founded on this territory, where more than 300 thousand people live now.

There were no permanent settlements on Murman until the middle of the XIX century. In 1868, Alexander II approved the “Regulations on the granting of privileges to the settlers of the Murmansk coast” [1, Engel'gardt A.P., p. 90]. As early as the following year, 46 families arrived to this territory, and according to data from 1899, 40 colonies were formed on the Murmansk coast with 2.185 residents [2, Statistical Studies of Murman. Colonization, p. 13]. Orthodox churches and chapels were built, schools, trading posts, commercial enterprises were opened, and sea trade was developing in the colonies.

The global problems of the development of the Arctic territories are widely presented in the theoretical literature and the media [3–8]. The colonization of the Murmansk coast of the Barents Sea, the implementation of state policy are devoted to the works of Ushakov I.F., Orekhova E.A., Davydov R.A., Korotaev V.I. The local specificity of the Arctic territories development in the field of family history, biographical research is considered in the works of Fedorova P.V., Razumova I.A. Nevertheless, the analysis of migrants’ way of life from the standpoint of the histo-

ry of everyday life requires more careful attention: during this period, permanent settlements appeared for the first time on the Murmansk coast and new ways of life arose in the extreme conditions of the north.

Methodology

“The history of everyday life is a branch of historical knowledge, the subject of which is the sphere of human everyday life in multiple historical, cultural, political, ethnic and confessional contexts” [9, Pushkareva N.L., p. 6].

The so-called “historical-anthropological turn” in the awareness of the events of the past begins in the second half of the twentieth century, changing the view on social history. A single universal picture of the world breaks up into many private, no less significant, phenomena. Theories of everyday life are formed in sociology and history. M. Maffesoli introduces everyday phenomena into the sphere of scientific analysis from a postmodern position [10, Maffesoli M.], N. Elias shows that everyday life is an integral part of any social group, and the historical process is the interaction of various social practices (labor, education, politics and so on)1, H. Lefèbvre considers subjective experiences as part of general models of reality [11, Lefèbvre H.]. French historians M. Blok, L. Fevr, F. Brodel' include various everyday phenomena (everyday life, housing, clothes, fashion, money, etc.) in the range of research problems and move from political history to the study of history in the context of psychological, demographic and cultural factors [12, Brodel' F.].

Scientists have proved that a special meaning, a system of values, and a cultural code are hidden in the history of everyday life. This is clearly shown with examples from Russian culture by Lotman Yu.M. [13, Lotman Yu.M.]. Scientific publications under the general title “Microstorie” began to appear at the end of the twentieth century. Scientists (K. Ginzburg, D. Levy and others) believed that the history of the private, individual is associated with a common identity and deserves close attention of researchers. In contrast to local history and ethnography, the history of everyday life focuses on the analytical part of the study, changes in the value system and the role of specific individuals in shaping a general picture of the world.

The main research method in this article is historiographic analysis. The object of analysis is the local (everyday) history of East Murman during the transition from temporary seasonal camps to permanent settlements. The collected complex of narrative information can be used in the future to clarify the features of the development of the Arctic territories.

The sources of historiographic analysis are essays, travel notes, memoirs compiled by travelers, writers Nemirovich-Danchenko V., Sluchevskiy K., Ostrovskiy D., Engel'meyer A., L'vov E. Colorful descriptions of everyday life, work, leisure, education, as well as short dialogues with local residents can be seen here. These sources present the author's assessment of the life of the migrants, figurative digressions, attention to the private. Brief mentions of the colonies of the Mur- mansk coast are given in the materials of Makarova S.O., Knipovich N.M. A special group of sources is the publications of officials who visited the Kola North (Minister of Finance Vitte S.Yu. Arkhangelsk Governor Engel'gardt A.P.), as well as geographical and socio-economic descriptions of the Murmansk coast, compiled by order of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, the Imperial Free Economic Society of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, the Arkhangelsk Society for the Study of the Russian North, the St. Petersburg Imperial Society to promote Russian merchant shipping, the Main Hydrographic Department of the Marine Ministry, the Committee for Assistance to the Pomors of the Russian North, provincial administrations. The descriptions of the provinces were compiled according to a specific plan, which, as a rule, indicated the population size, types of economic activities, religion, education (“Murman”, A.G. Slezskinskiy, “Materials on statistical research of Murman” edited by Romanov N.V.). All the listed sources are unique testimonies of the life of settlers, written by the participants of the expeditions on the basis of reliable data and from the words of the colonists, confirming that permanent settlements were formed on the site of seasonal settlements, with a certain number of houses, specific residents and families.

Colonies of East Murman

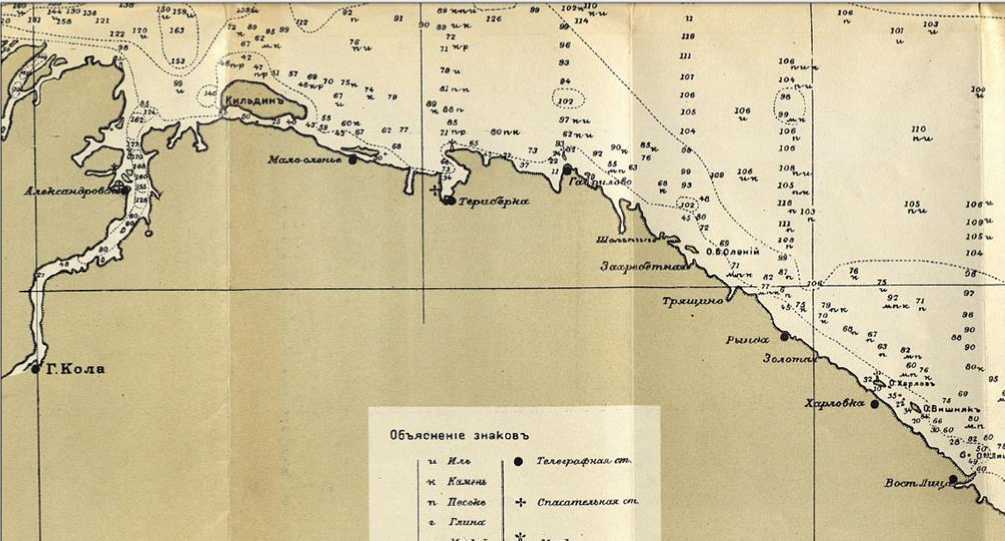

East Murman is the territory of the Barents Sea coast to the east of the Kola Bay up to Cape Svyatoy Nos. According to the census of 1608, there were 29 settlements. The most significant settlements at the beginning of the 17th century were in Gavrilovo and Teriberka. Permanent settlements appeared only in the second half of the 19th century.

According to the materials of the statistical study of East Murman and the Kola Bay in 1902, there were 25 settlements (encampments and colonies) on this territory: Vostochnaya Litsa, Khar-lovka, Zolotaya, Rynda, Shel'piny, Gavrilovo, Golitsyno, Teriberka, Malo-Olen'e, Zarubikha, Tyuva-guba, Tryashchina, Shcherbinikha, Zakhrebetnaya, Zelentsy, Srednyaya Guba, Vaenga, Gryaznaya Guba, Roslyakova Guba, Belokamennaya, Krasnaya Shchel', Sayda-Guba, Vodvora or Olen'ya Guba, a colony at the Toros Islands, Kildin Island [14, Materials on Statistical Research ..., p. 1]. Unlike villages and settlements widespread throughout Russia, the main types of settlements on the Murmansk coast were camps and colonies — seasonal and permanent fishing settlements on the sea coast.

This article will focus on ten colonies of the East Coast (Vostochnaya Litsa, Kharlovka, Ryn-da, Shel'piny, Gavrilovo, Golitsyno, Teriberka, Zolotaya, Zarubikha, Malo-Olen'e) and the Kildin colony (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. East Murman. Fragment of a map from the book by Sidensner A.K. “Description of the Murmansk Coast” (St. Petersburg: Main Hydrographic Department of the Marine Ministry, 1909).

Before making an overview of the colonies of East Murman, we outline a number of social aspects that we will consider. They are home life, daily work, religious beliefs, schooling, and leisure. We will pay special attention to the indication of specific surnames and names, family ties. In general, the history of everyday life includes a wide range of phenomena; however, the specificity of a given area in the period under study makes it possible to analyze only those phenomena that are recorded in the sources. In particular, ethnographic expeditions to study the Russian population were not carried out here, since the colonization was of a temporary nature. For the same reason, the internal (stationary) artistic culture (fairy tales, legends, applied art) was practically not recorded.

From the descriptions, we learn the time of the creation of the first colonies. It is important that the specific names of the first settlers are indicated: Vasiliy Naumov, Dmitriy Dmitriev, Ivan Petrov, Il'ya Tarnakh, Eftyukov, Ivan Red'kin, Dmitriy Semenov, Eremey Borodkin, Ivan Erikson. The choice of a place for settlement, as a rule, depended on the fishing grounds. Colonies were often formed not far from the encampments, where industrialists gathered every spring to catch cod, halibut, and hunt sea animals. According to Fedorov P.V., the colonization of Murman was a deeply Russian phenomenon, a consequence of the tradition of the development process, which from time to time passed to new stages — from a seasonal form to a permanent population and from a rural to an urban way of life, “the result of an internal, distinctive process, during which various forms of life of the Russian population arose in Murman” [15, Fedorov P.V., p. 42].

Let us cite the data indicated from the words of the colonists from “Materials on the statistical study of Murman” and the book by A. Slezskinskiy “Murman”. In some cases, they do not coincide (Persons, Shelpins) or clarify each other (Rynda). “According to the colonists, the colony of

Litsa was founded in 1880. The first who settled there was a peasant from the Kemskiy district, Kandalakshi village, Foma Redkin” [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 8]. “The first colonist who lived here for the winter was a peasant from the village Kandalaksha, Kemskiy district, Vasiliy Naumov” [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 4]; the first man who came to Shelpino in 1890 and “settled there without permission was the Finnish Il'ya Tarnakh; and the previous year the peasant of the Onega district Eftyukov settled down” [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 8], “the first settlers of the colony were the Daarnak family: Wilhelm with his wife, Marya Ivanovna” [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 87]; colony Kharlovka was formed in 1894, the first who came there was a peasant of the Kemskiy district from the village of Pot’bozero Dmitriy Dmitriev [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 13]. “The first who settled in Rynda, in 1875, was the peasant of the Kemskiy district of the village of Chernoretskaya Ivan Petrov" [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 17]; “The first colonists were Ivan Petrov and Fedor Lipaev – now dead. Later — Pavel Lopinov and Kornil'ev” [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 48]. “Gavrilovo is one of the oldest Murmansk colonies formed in the 1940s; its founder was a peasant of the Kemskiy district, a Karelian, Ivan Red’kin” [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 31]. Colony Kil’din was founded in 1880 by the Norwegian Ivan Erikson. “Since this Norwegian settled on Kil’din, no one wanted to move there; so, he has been on Kil’din for 15 years alone, as if he were the sovereign face of the island” [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 45].

Further Zolotaya colony arose in 1898, when the first colonist, Aleksey Vasil'evich Ivanov-Anikeev, a peasant of Tungudskaya volost, Kemskiy district of the Mashozero village settled there; the second colonist Matveev settled in August of the same year; Malo-Olen'e, as a colony, has existed since 1898, the first settler there was Karelian Lukkoev from the Ukhta volost; Zarubikha's first permanent resident was the peasant of the Notozero churchyard, Yakov Fedorov Abalyaev, who lived there until his death in 1893; the first to express a desire to resettle in Teriberka were the peasants of the Ion’gam volost of the Kemskiy district — Savin and Semenov [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 30, 180, 192, 137].

Further in the history of the settlement of East Murman, the names of the settlers (wives, children, brothers) were preserved. So, in the spring of 1881, Foma Red’kin arrived in Vostochnaya Litsa with a family of seven. Vasiliy and Ivan then settled in Gavrilovo, then in Golitsyno. Then Fedor Nemchinov from Kandalaksha with his family, Fedor Semyonov from Pongama, Sergey Zhidkikh from Kandalaksha settled in Litsa. The sources also describe individual events from family history. So the fate of the Lukkoev family from Malo-Olen’e was very dramatic: the head of the family died, leaving his wife with two children. She went to winter in Kola, then in Vardø. The widow of Lukkoev returned to Malo-Olen’e with her new husband Eremey Borodkin and his two children. Arseniy Simakov's wife could not survive the first winter and died of scurvy, leaving four children, and he moved to Teriberka. Stepan Lopintsev from Zarubikha waited ten years for the promised allowance, then he went to the Kola groundlings [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 5, 6, 180, 181, 193]. Restoring family-related structures is an important scientific task, the solution of which will make it possible to personify history and requires further study.

In the studies of East Murman it is possible to find names, place of birth, number of children and individual episodes from the life of the colonists Anan'in, Strelkov from Kharlovka, P.M. Ivanov and An.St. Evstigneev from Shel'pina, Stepan Lopintsev, Andrey Polezhaev, Ponomarev, Mednikov from Zarubikha, Dem'yan Kharchev. These data supplement and clarify statistics. In particular, the petty bourgeois Kononov, who was assigned to the Teriberian colonists in 1870, “is known throughout the seaside for his knowledge and experience in skipper business, which he acquired partly in one of the local skipper schools, and partly during repeated skipper's trips to England, Spain, to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea” [17, Polenov A.D., p. 24]. The surnames of the colonists are also recorded in the “Questionnaire Survey of Murmansk Fisheries “ conducted by the Pomor department of the Arkhangelsk Society for the Study of the Russian North and published in 1913. Here you can get acquainted with the answers of the colonists Kolyshnev M.G. from Rynda, Korol’kov I.S. from Gavrilovo, Pakulin A.I. from Teriberka and others [18, Questionnaire Survey, p. 12].

There are many references to the appearance and character of the colonists In the works of writers who visited Murman. Sluchevskiy K. in the book “Around the North of Russia”, characterizing the appearance of the inhabitants of Murman, describes “their coarse clothes, their dark hats, boots, bast shoes, bare feet" [19, Sluchevskiy K.K., p. 294]; Nemirovich-Danchenko V. I. in the book “The Country of Cold” characterizes the hunters as “a hardy and beautiful tribe, brave, smart and enterprising” [20, Nemirovich-Danchenko V. I., p. 95]. Some episodes about the inhabitants of the Far North can be found in the books of Prishvin M. and the memoirs of Korovin K. A brief description is given in the well-known book by Lvov E. “On the Cold Sea: A Trip to the North”, which describes the expedition of the Minister of Finance Witte S.Yu. in summer of 1894 for the construction of an ice-free port. “In Teriberka, a purely Russian colony begins to settle, and several dozen families have already settled here firmly...” The Minister of Finance was greeted by about 800 people, the inhabitants of the camp and the colony “all stocky men with thick beards, with gray, intelligent and energetic eyes ... They behaved with a kind of calm natural dignity that inspires respect” [21, L’vov-Kochetov E.L., p. 113].

Colonist lifestyle, daily activities, domestic life

The settlers experienced a lot of difficulties: the lack of warmth, firewood, timber, lack of communication, schools, and churches. Besides, it was a big problem to get the loans and permission to settle.

At the same time, there are sharply negative characteristics: “Colonization of this coast is even more vital incongruity”; “In reality, these benefits turned out to be very small, at least for the Russian colonists” [25, Manotskov V.I., p. 144, 150]. “In general, it should be said that all the privileges granted to the Russian colonists by the Regulations of 1868 turned out to be insufficient in comparison with the obstacles and troublesome formalities that had to be overcome when obtaining the right to resettlement” [26, Sidensner A.K., p. 18]. Many researchers point out that government colonization measures must take into account local conditions. “Concerns about settling in are not just limited to giving the colonist an allowance or building a good hut for him,” it is necessary “that these huts are located in an area convenient for life, for organizing an economy,” reported Shavrov N.A. at a meeting of the St. Petersburg Imperial Society for the promotion of Russian merchant shipping [27, Shavrov N.A., p. 70].

The harsh living conditions of the colonists are confirmed in the sources by specific examples. In particular, in the Zolotaya colony, the house of the widow Matveeva was a small shed made of planks, adapted for living in the summer. In winter, the Matveevs lived in the camp of a single industrialist. According to the colonist Anikeev-Ivanov, the cost of building a house, despite its insignificance, is very high: “There are no workers, you work all by yourself and instead of fishing you sit by the hut.” The first years In Teriberka were very difficult for the settlers; “They sold everything at home and became impoverished because of hunger; in the new place they received only 150 rubles, and then three times. There was no home or livestock. The husband (Savin) traded at sea, the children were small. The desertion in winter was also hard: no church, no people.” The first winter In Malo-Olen’e was snowy: “From the house door we had to climb a snowy staircase 1 sazhen high; the windows also had to be torn off after each snowstorm. Once, traveling with the whole family to Teriberka for reindeer, we got lost in a blizzard, escaped in a snow pit under the shroud (under their clothes) for 3 days and 3 nights and almost died from the cold. When we returned home, we barely found our hut: it was completely covered with snow” [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 81, 82, 137, 180]. But their unsettled life was compensated by their firm spirit and desire to live and work there.

The main economic activity in all colonies is fishing. Almost all sources consider this issue. Families in Murman gradually settled down and found profitable occupations. They caught cod, haddock, halibut, catfish, and flounder. The main fishery (cod) started in March and ended in early October. In autumn, the colonists knitted nets, renovated houses, and cut firewood. Women in the summer were busy with housekeeping, collecting lichen. “Women are mainly engaged in baking bread, and partly (for the most part along with bread-baking) unwinding bales and washing clothes [28, Romanov N.V., p. 14]. In Vostochnaya Litsa, two years later, the Red’kin family moved to a new house. “He gets his livelihood sustenance from the animal trade, ... salmon catch”, Wilhelm Daarnak from Shelpino: “The means of subsistence were: fishing in summer, the guard of Savin's trading post — in winter. In the spring we hunted with Savin on his nets. His wife ... supports existence by fishing and selling milk in summer, leasing barns to industrialists, selling wool from sheep and deer for meat” [14, p. 6, 87].

Each family has its own circumstances of settling on the Murmansk coast. Basically it is the need and desire for free fishing activities. The first colonists said: “You will never come here from a good life”, “They ate the bark, people got swollen and died”, “We went unwillingly, like into exile,” but then they come here “from bondage”, hoping for a better life [29, Preliminary Report, p. 1]. Dmitriev D. “had to drive out of the house of the Kemskiy district: his house burned down, then the cattle fell. I chose Kharlovka because I had lived here for years and previously, had acquaintances with industrialists, and could count on their help.” In Colony Zolotaya, according to Anikeev, “he was forced to move by necessity: a large family, but there is not enough land for cultivation, and even that land is bad; mowing is bad. Every year I went to Murman, spent 20 rubles on the road. I thought: if I move, there will be no transportation”. In Malo-Olen’e, the son of a psalmist from Vorzogor “used to live in “someone else's work”, visited, by the way, St. Petersburg!” In Za-rubikha, “the peasant Ponomarev from Kolezhma, Kemskiy district went to fishing or hunting from the artel, the family is large, there was no support, and therefore he decided to “pisat'sya” [14, p. 20, 31, 181, 193].

The descriptions of the colonists' houses and the general impression of scientists and travelers from the colonies are of special interest. On the one hand, the participants of the expeditions talk about the harsh climate, on the other hand, about the solidity of the buildings and the security of the inhabitants. Here is how Slezkinskiy A. describes one of the colonies: “Opposite the mouth of the river Kharlovka colony and camp Kharlovka are located. The high rocky shores around, without any flora, they look somehow mysterious, scary. At the foot of these gloomy giants some huts are seen — people live there and it becomes extremely creepy for them; one cannot help thinking, how do they live here, side-by-side with the constantly raging Arctic Ocean? “ [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 12]

Many colonists began to live in barns and dugouts. A dugout was built in the following way: the frame was made of a row of thin timber-racks driven into the ground; all the construction was lined with wide pieces of turf, laid horizontally one on top of the other, so that the soil layer reaches a thickness of 0.7 meters. The gaps between the racks were sheathed with boards, but more often there was soil between the racks. There was no ceiling in most cases. There was only a binding of horizontal logs instead, between them the roof was visible, they were supported by a binding of poles. The roof had four sloping surfaces, covered with turf on the outside. “A dugout always smells of soil. But the main disadvantage of a dugout is dampness; there is less dampness in old dugouts, but in new ones, where the sod has not dried out yet, it is very damp, and since the dugout often has to be corrected, replacing old pieces of sod with new ones, the dampness in dugouts does not disappear” [2, p. 116].

However, after a few years, researchers noted that the colonists' huts were new, they generally live prosperously. In Vostochnaya Litsa “the huts are exceptionally wooden, durable, and comfortable"; the settlement of Rynda “looks decent, and some huts even show to the prosperity of the owners"; in Gavrilovo “the colonists are financially secure. Their houses are solid, good, they have no shortage of life supplies”, in Galitsyno “the houses in the colony are decent; the colonists live without poverty — there is enough bread, fish, and forests”; in Teriberka “in general, the colonists' huts are good. Their comfortable life attracts many immigrants” [16, Slezskinskiy A.G., p. 11, 17, 32, 37, 42]. In the Kil’din colony “the house of the Norwegian colonist Ivan Erikson is an example of Murmansk buildings. The house is wooden, two-storey, with a porch, a balcony and a flagpole, without foundation, covered with sod. The house is warm, the family is large, growthy, healthy, friendly. They live prosperously and neatly” [30, Ostrovskiy D.N., p. 99].

“A typical house of a colonist is 3–4 sazhens in one and the other direction and 3–4 arshins heights. As a rule, at first there was a small hut without a canopy and outbuildings, then a canopy was attached to it; behind them a new, equally small or larger hut, barn and other outbuildings were made. In Rynda, all the colonists had small wooden, one-story houses. Only one house had four windows on the facade, the rest had three and two windows. One colonist has a house covered with turf for warmth. Some houses are sheathed on the outside. Houses are built at a considerable distance from each another. It's clean and dry outside in summer. There are few commercial camps near the colonies. In Shelpino, the house of the colonist Daarnak differs sharply from others. This is the typical house of a middle-class Finnish colonist. Outside, it is a long quadrangular building in which living space and some others are located under one roof. In Teriberka, the houses are small, one-story, with three windows along the facade, rarely more. Sometimes they are sheathed with boards. Colonists with livestock built premises for livestock under the same roof with a house. Barns are often attached to houses, often separately. All houses have separate kitchens” [14, p. 111, 50, 89].

The researchers left us a description of the interior of the colonists' house. A typical large house has two, sometimes three rooms in addition to the kitchen. The entrance to the rooms is often through the kitchen. In Rynda, the walls inside the houses are either painted or covered with wallpaper. “In general, the interior of some people resembles a peasant hut with long benches on the walls, an unpainted table in the front corner; the interior of others looked like the furnishings of a poor room in a provincial town: wooden, bungle-made chairs are painted like tables and walls. There are no painted floors.” In Shelpino, colonist Daarnak has a hallway in the middle of the building, on one side there are two rooms for living, on the other — outbuildings. The first room from the entrance is the kitchen, which is also the dining room. It is illuminated by two windows. “There is a large Russian stove, which is heated daily in winter and for baking bread, etc. In addition to it, there is a fireplace, which is heated daily for warmth, cooking food, coffee. The room next to it is a bedroom and living room — this is the “clean half”. It is illuminated by one window.” In Teriberka, the houses of the colonists are usually divided into two halves by partitions. “The furnishings of wealthy colonists are somewhat reminiscent of the city: chairs, tablecloths. But, as a general rule, in old houses benches along the walls can be found. Not all of them have beds. All family members sleep side by side in one room” [14, p. 50, 89, 140].

Religious traditions, schooling, leisure time

The inhabitants of East Murman are practically all Russian, Orthodox, with the exception of Kil’din. That is why the shore was called “Russian”. The Orthodox colonist population of East Murman was concentrated in the parishes of Lovozerskiy, Gavrilovskiy, Teriberskiy. An important source for studying the social history of Eastern Murman is the registers of birth, containing official records of acts of birth, marriage and death.

The Lovozerskiy parish included the colonies of Rynda, Zolotaya, Kharlovka and Vostochna-ya Litsa. The entire parish stretched for at least 300 miles. There is one priest and one psalmist for this huge space. There were churches in Rynda and Kharlovka, in Vostochnaya Litsa — a chapel. The Gavrilovo parish included the colonies of Gavrilovo, Golitsyno, Shel’piny, Zakhrebetnaya and the Tryashchina camp. There is a church and a chapel in Gavrilovo; there is a chapel in Shelpino. The church in Gavrilovo was built in 1895, and the parish was opened at the same time. Both chapels are very old (in Gavrilovo it was founded in 1797, in Shelpino it has existed for over 200 years). The Teriberskiy parish was founded in 1886, it includes Teriberka, Malo-Olen’e and Za-rubikha. In winter, communication is hampered by “bad weather, lack of roads, lack of stations and supplies” [2, Statistical Studies of Murman. Colonization, p. 76].

In Rynda the colonists are all Russian, Orthodox, moved from the Kemskiy district. A small church was built in the colony, and a church service is performed by a local priest. “The temple is visited by the worshipers fervently, especially in winter, when the colonists are less busy”, in Khar-lovka “the colonists from Karelians, Orthodox, have a church, which was built not for them, but for the newcomers Pomors.” Both the colonists and especially the industrialists are mostly Old Believers, but there is no strict adherence to their rituals. More colonists and few industrialists go to church. Not everyone goes to confession; partly due to the fact that the priest cannot come to the colony in winter, and in the summer everyone is busy with fishing. In the Kil’din colony “all the colonists are Russian, from the Norwegians, they speak exclusively Norwegian, they have no relations with the Russian colonists, and they do business in Norway” [16, Slezkinskiy A., p. 13, 19, 45].

Primary education in the settlements of East Murman was provided to children in Teriber-ka, Gavrilovo. In Vostochnaya Litsa, Kharlovka, Golitsyno, residents generally did not know how to write, there were no schools for children, in Rynda there were literate residents, but no education was provided for children. In East Murman, 78 men and 24 women, 18 boys and 3 girls were literate. The most literate among the colonists are those who have recently migrated, who have managed to learn at the place of their former residence. Their children, who were born on Mur-man, in most cases, remain completely illiterate, despite their relative prosperity [2, p. 19].

In Vostochnaya Litsa, “the colonists are all almost illiterate; besides, there is no one who brings a letter here; even the lower ranks do not enter it, because the colonists are exempted from military service”; in Kharlovka “no adults knows literacy, but it is very difficult to imagine that it would penetrate to their children”, in Rynda “there are some literate colonists, but they learned it not in the colony, but at home and they cannot pass the literacy to the new generation, so children grow illiterate”; in Gavrilovo “the church has a literacy school, where 6 boys study. This good deal is conducted by a priest and a sexton for free, and teaching aids are bought by the parents”; in Golitsyno “some of the colonists are literate and it is those who moved there from Gavrilovo, but the younger generation grows illiterate” [16, Slezkinskiy A., p. 10, 14, 19, 32, 37].

In Teriberka, the literacy school “exclusively educates the children of local colonists. The Law of God is taught by a local priest, other subjects — by a psalmist. The priest was educated at home, and the psalm-reader was dismissed from the first class of the theological seminary. There were students in the school: 10 boys in 1898/99. The course is two years. School time is from early October to early April. The school, according to the priest, does not need anything. But the local colonists complained that the school teaching is very sloppy: “scampish learning”: they teach for one day, but do not teach for two days. And they teach little: the boys will gather and run for about an hour in front of the school; then they study for an hour, and then they go home to have dinner. After lunch they have a new rush and classes again for no more than an hour, and then back home. The test of two students, Neronin, who studied for two years, and Sinyakov, who studied for 3 years, gave the following results: the first was reading in syllables; Sinyakov did not read very quickly either. Both count poorly. They know little of prayers [14, Materials on Statistical Research, p. 144].

In their free time (late autumn and winter), young people gather in the evenings for sittinground and for fun. For this purpose, they usually rent a hut from one of the colonists who do not live there during the winters. “The Appendix to the Description of the Gavrilovo colony” describes how the colonists spent the winter of 1899–1900: “A family (7 people) occupies 2 small rooms in winter. Apart from the most basic necessities like cooking, mending clothes, preparing firewood, etc., the widow and the children have no other activities” [14, Materials on Statistical Research of Murman, p. 127].

Festive culture is the opposite of everyday culture; however, all elements of the holiday (festive clothing, food, rituals, songs) in the colonies practically do not differ from everyday life. They don't go fishing on holiday. In the summer, on holidays, they are going to play pitching pennies. In Rynda, on holidays, they rarely go to the sea, although in the evening they catch bait. “They even caught it during the Transfiguration day, on their patronal feast day. This is explained partly by the fact that there are many Old Believers among industrialists, and partly by the fact that there is little bait here. There is not much drunkenness. It also does not strike the eyes be- cause there are few people and they are dispersed over a significant area.” “In winter there is black bread for eating; white bread is on holidays.” In Teriberka, holidays are considered as days of rest. “They don't go fishing, unless they are at sea on holidays. There are no entertainments in summer. By the evening of a holiday they are already starting to work — they catch the bait, bait the longlines. Generally speaking, the population is modest and reserved — even industrialists. Nine statisticians worked on a holiday (conducted interviews) and none of them can complain of rudeness even from the drunk people” [14, p. 51, 112, 140, 141].

Thus, the descriptions of the life of the settlers (everyday activities, the atmosphere at home, the circumstances of entering the area, religious traditions, schooling, leisure time) preserved in the materials of expeditions and travel notes allow us to see the important role of an individual and family in the processes of adaptation to extreme conditions of the north. The stories from the life of the colonists give an emotional coloring to the events taking place and form a sense of belonging and mental appropriation of territory. The process of the formation of colonies (building houses with adjacent outbuildings, everyday activities) is a unique experience in the development of the Arctic territories. In general, the reconstruction of the typical helps to determine the motivation of a particular person and his family to live in the north, the evolution of the value system and possible scenarios for the future.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of the origin of cultural localization in a new place described in the article could not be formed: the colonization project in the Soviet period was implemented in a different format. It is all the more important to study the problems and results of this project, as well as new scientific research and discussions based on the reading of primary sources. The formation of the regional integrity of East Murman took place gradually, following the settlement by people from different regions. The new territory was appropriated not only officially (through the accrual of benefits) or symbolically (by building churches), but also in the minds of the settlers themselves. The analysis of the corpus of scientific texts and materials of expeditions makes it possible to analyze the memories of eyewitnesses about the specifics of adaptation, family history, events and the surrounding space during the study period, and the collection of data about specific people mentioned in the sources is a preparatory stage for a large-scale study of demography and family-related structures of the Murmansk coast.

Acknowledgments and funding

The article was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research: project 20-0900008 “Russian Arctic: from camps to “colonies” (adaptation, family, culture)”.

Список литературы Eastern Murman: social aspects of colonization in the materials of expeditions and travel notes of the 2nd half of the 19th - early 20th centuries

- Engel'gardt A.P. Russkiy Sever: putevye zapiski [Russian North: Travel Notes]. Saint Petersburg, Iz-datel'stvo A.S. Suvorina, 1897, 258 p. (In Russ.)

- Statisticheskie issledovaniya Murmana. Kolonizatsiya (po materialam 1899, 1900 i 1902 gg.) [Statis-tical Studies of Murman. Colonization (Based on Materials from 1899, 1900 and 1902)]. Saint Pe-tersburg, Tipografiya I. Gol'dberga, 1904, 291 p.

- Avdonina N.S., Dolgoborodova S.O. Osveshchenie geopoliticheskoy problematiki v kontekste temy osvoeniya Arktiki v amerikanskom mediadiskurse (na primere materialov gazety «The New York Times») [Covering Geopolitical Problems in the Context of the Arctic Exploration in the American Media Discourse (Based on The New York Times Content Analysis)]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2018, no. 33, pp. 178–191. DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.178.

- Avdonina N.S., Vodyannikova O.I., Zhukova A.A. Osveshchenie problem Arkticheskogo regiona v sovremennoy mezhdunarodnoy zhurnalistike: primery i osobennosti [The Problems of the Arctic Region in Modern International Journalism: Examples and Features]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2019, no. 34, pp. 134–138. DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2019.34.159

- Bhagwat J. Rossiya i Indiya v Arktike: neobkhodimost' bol'shey sinergii [Russia and India in the Arc-tic: A case for greater synergy]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2020, no. 38, pp. 73–90. DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2020.38.73

- Korchak E.A. Dolgosrochnaya dinamika sotsial'nogo prostranstva arkticheskikh territoriy Rossii [The Arctic Territories of Russia: Long-Term Dynamics of the Social Space]. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2020, no. 38, pp. 123–142. DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2020.38.121

- Heininen L. Obzor arkticheskoy politiki i strategiy [Overview of Arctic Policies and Strategies]. Arkti-ka i Sever [Arctic and North], 2020, no. 39, pp. 195–202. DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2020.39.195

- Heininen L. The Arctic Region as a Space for Trans-disciplinary, Resilience and Peace. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2015, no. 21, pp. 69–73. DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2015.21.81.

- Pushkareva N.L., Lyubichankovskiy S.V. Ponimanie istorii povsednevnosti v sovremennom is-toricheskom issledovanii: ot Shkoly Annalov k rossiyskoy filosofskoy shkole [“Everyday Life History" in Modern Historical Research: from School of the Annals to the Russian Philosophical School]. Vest-nik Leningradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta im. A.S. Pushkina, 2014, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 7–21.

- Maffesoli M. The Sociology of Everyday Life (Epistemological Elements). Current Sociology, 1989, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 1–16.

- Lefèbvre H. Everyday Life in the Modern World. L. Harper & Row, 1971, 210 p.

- Brodel' F. Struktury povsednevnosti: Vozmozhnoe i nevozmozhnoe [Structures of Everyday Life: Possible and Impossible]. Material'naya tsivilizatsiya, ekonomika i kapitalizm, XV — XVIII vv. V 3-kh t. [Material Civilization, Economy and Capitalism, 15th – 18th Centuries]. Moscow, 1986, vol. 1, 621 p. (In Russ.)

- Lotman Yu.M. Besedy o russkoy kul'ture: Byt i traditsii russkogo dvoryanstva (XVIII — nachalo XIX veka) [Conversations about Russian Culture: Life and Traditions of the Russian Nobility (18th - Early 19th Century)]. Saint Petersburg, Iskusstvo Publ., 1994, 481 p. (In Russ.)

- Romanov N.V., ed. Materialy po statisticheskomu issledovaniyu Murmana. V 4 tomakh. T. 2. Vyp. 1. Opisanie koloniy Vostochnogo berega i Kol'skoy guby [Materials on Statistical Research of Murman. In 4 Vol. Vol. 2. Iss. 1. Description of the Colonies of the East Coast and the Kola Bay]. 1902, XIX, 273 p. (In Russ.)

- Fedorov P.V. Kul'turnye landshafty Kol'skogo Severa: struktura i istoricheskaya dinamika [Cultural Landscapes of the Kola North: Structure and Historical Dynamics]. Murmansk, MSHU Publ., 2014, 175 p.

- Slezskinskiy A.G. Murman [Murman]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya I. Gol'dberga, 1897, 219 p. (In Russ.)

- Polenov A.D. Otchet po komandirovke na Murmanskiy bereg [Report on a Business Trip to the Murmansk Coast]. Saint Petersburg, 1876, 56 p.

- Anketnoe obsledovanie murmanskikh rybnykh promyslov [Questionnaire Survey of Murmansk Fish-eries]. Arkhangelsk, Gubernskaya tipografiya, 1913, 18 p.

- Sluchevskiy K.K. Po Severo-Zapadu Rossii. T. 1: Po Severu Rossii [In the North-West of Russia. Vol. 1: In the North of Russia]. Saint Petersburg, Izdanie A. F. Marksa, 1897, 456 p. (In Russ.)

- Nemirovich-Danchenko V.I. Strana kholoda: vidennoe i slyshennoe [The Land of Cold: Seen and Heard]. Saint Petersburg, Izdanie knigoprodavtsa-tipografa M.O. Vol'fa, 1877, 260 p. (In Russ.)

- L'vov-Kochetov E.L. Po Studenomu moryu: poezdka na Sever: Yaroslavl', Vologda, Arkhangel'sk, Murman, Nordkap, Tronkheym, Stokgol'm, Peterburg; s risunkami s natury, ispolnennymi khudozh-nikami K.A. Korovinym i V.A. Serovym; dopolneno v 2019 godu rabotami khudozhnika A.A. Borisova i fotografa Ya.I. Leytsingera [On the Cold Sea: a Trip to the North: Yaroslavl, Vologda, Arkhangelsk, Murman, North Cape, Trondheim, Stockholm, Petersburg; with Drawings from Nature, Performed by Artists K.A. Korovin and V.A. Serov; Supplemented in 2019 by the Works of the Artist A.A. Borisov and Photographer Ya.I. Leuzinger]. Murmansk, Danilova T.N. Publ., 2019, 251 p.

- Makarov S.O. «Ermak» vo l'dakh [“Ermak» in the Ice]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya E. Evdokimova, 1901, 508 p. (In Russ.)

- Lashkarev O.S. Besedy o Severe Rossii v 3 otdelenii Imperatorskogo Vol'nogo Ekonomicheskogo Ob-shchestva [Conversations about the North of Russia in the 3rd Branch of the Imperial Free Economic Society]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya Tovarishchestva «Obshchestvennaya Pol'za», 1867, 461 p. (In Russ.)

- Engelmeyer A.K. Po russkomu i skandinavskomu severu. Putevye vospominaniya [Through the Rus-sian and Scandinavian North. Travel Memories]. Moscow, Tipografiya G. Lissnera i A. Geshelya, 1902, 210 p. (In Russ.)

- Manotskov V.I. Ocherki zhizni na Kraynem Severe. Murman [Sketches of Life in the Far North. Murman]. Arkhangelsk, Tipolitografiya S.M. Pavlova, 1897, 193 p. (In Russ.)

- Sidensner A.K. Opisanie Murmanskogo poberezh'ya [Description of the Murmansk Coast]. Saint Petersburg, Glavnoe Gidrograficheskoe Upravlenie Morskogo Ministerstva, 1909, 272p. (In Russ.)

- Shavrov N.A. Kolonizatsiya, ee sovremennoe polozhenie i mery dlya russkogo zaseleniya Murmana [Colonization, its Current Situation and Measures for the Russian Settlement of Murman]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya I. Gol'dberga, 1898, 98 p. (In Russ.)

- Romanov N.V. Organizatsiya i programma statisticheskikh rabot na Murmane v 1902 godu [Organi-zation and Program of Statistical Work on Murman in 1902]. Arkhangelsk, 1902, 22p. (In Russ.)

- Predvaritel'nyy otchet po issledovaniyu kolonizatsii i promyslov Murmanskogo berega otryadom statistikov, komandirovannykh na sredstva Komiteta dlya pomoshchi Russkogo Severa [Preliminary Report on the Study of Colonization and Fisheries of the Murmansk Coast by a Detachment of Stat-isticians Sent on a Mission to the Committee to Help the Russian North]. Saint Petersburg, Tipografiya I. Gol'dberga, 1900, 57 p.

- Ostrovskiy D.N. Putevoditel' po Severu Rossii: (Arkhangel'sk. Beloe more. Solovetskiy monastyr'. Murmanskiy bereg. Novaya zemlya. Pechora) [Guide to the North of Russia: (Arkhangelsk. White Sea. Solovetsky Monastery. Murmansk Coast. New Land. Pechora)]. Saint Petersburg, Izdanie Tova-rishchestva Arkhangel'sko-Murmanskogo parokhodstva, 1898, 146 p. (In Russ.)