Enhancing Employee Engagement through Machine Learning: Insights from K-Means Clustering Analysis

Автор: Hemanth Kumar Tummalapalli, G. Kamal, Y.V. Naga Kumari, J.N.V.R. Swarup Kumar, Y. Chitra Rekha

Журнал: International Journal of Education and Management Engineering @ijeme

Статья в выпуске: 6 vol.15, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study provides insight into how machine learning methods, in particular k-means clustering algorithm could contribute to greater degree of employee engagement in the businesses. Using Work-Life Balance, Environment Satisfaction and Job Satisfaction found in employee survey data as an illustrative lens of the engagement phenomenon, patterns are identified that differ from traditional perspectives with implications for organizational actions. The study categorizes workers in clusters and identifies the significant gaps of satisfaction among them, using k-means clustering. Logistic regression analysis is used for the prediction of attrition risk, which also helps in determining factors responsible behind employee retention. The findings reveal the importance of understanding such facilitators to generate targeted interventions and strategies that foster a positive work environment and improve organisational performance. This approach ensures less attrition risks, and better job satisfaction leading to greater overall organisation productivity / wellbeing.

Employee Engagement, Machine Learning, K-Means Clustering, Survey Analysis, Organizational Strategy, Attrition Prediction

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15020049

IDR: 15020049 | DOI: 10.5815/ijeme.2025.06.02

Текст научной статьи Enhancing Employee Engagement through Machine Learning: Insights from K-Means Clustering Analysis

High levels of employee engagement are vital if organizations are going to compete in the knowledge-based economy [1, 2]. Engagement is defined as the emotional bond to an organization [3, 4] and has significant impact on job satisfaction, retention or customer satisfaction. Nevertheless, the complexity of engagement is occasionally disregarded by popular procedural records in quantifying it [4, 5].

The transformation of data analytics and machine learning has been a big change in knowing employee engagement. However, existing research often falls short in operationalizing employee engagement into actionable clusters that HR managers can directly use. Many prior studies either use traditional survey analysis without segmentation or do not explore unsupervised ML methods to discover hidden engagement profiles.

This study aims to fill this gap by applying k-means clustering to uncover latent engagement patterns in workforce survey data and connect these insights to actionable retention strategies. This is particularly seen in the exploration of the k-means clustering technique [6] . K-means clustering is a machine-learning algorithm, an unsupervised one, that can group employees effectively according to their general attributes, leading to useful information about engagement dynamics [7, 8] . This method has been utilized to subdivide labour forces by using variables such as work-life balance and job satisfaction [9] .

K-means clustering is one of the most effective algorithms for real-world applications established by research studies. According to [10] , among the nurse educators garnered all the efforts, almost some of them go to the extent of getting burnt so that in the end, they cannot handle the things properly. In contrast, [11] applied this theory for predicting the employee attrition. While the study conducted by [12] identified the student engagement patterns in online learning, the study carried out by [13] evaluated its performance in big data business process management. Hence, it is resilient to different applications of k-means clustering, such as student engagement in online learning [14, 15] .

K-means clustering is particularly suited for employee survey data as it efficiently groups employees based on similarities in engagement-related features (e.g., job satisfaction, environment satisfaction). Its ability to uncover latent patterns without prior labels makes it ideal for exploratory analysis where predefined classes are unavailable. This helps HR professionals move beyond generic averages and discover nuanced subgroups within the workforce.

The efficiency of k-means is enhanced when combined with other methods. For instance, [16] introduced a hybrid approach for classifying occupational risk data, while [17] linked it with picture fuzzy datasets to examine organizational identification.

The study explores how identifying different engagement patterns within the workforce through k-means clustering can enhance employee engagement initiatives. The study shows how firms can utilize these findings to formulate HR strategies that are specifically geared at developing employees that is more engaged and motivated. In addition to providing insightful information for HR professionals and leaders, the study includes a case study that shows how k-means clustering may be used practically in a real-world setting.

To ground the machine learning approach in theory, this study adopts the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model as its conceptual lens. The JD-R framework posits that employee engagement arises when job resources (e.g., job satisfaction, supportive environment) outweigh job demands (e.g., poor work-life balance). By clustering employees based on these engagement indicators, this study applies machine learning not merely as a statistical tool but as a means of operationalizing key theoretical constructs to identify resource-demand imbalances across workforce segments.

2. Literature Review 2.1 Employee Engagement

Given that engaged workforce is typically more productive, satisfied, and have lower turnover rates, employee engagement is a crucial component of both organizational performance and worker well-being. Engagement was described by [18] as the rational, emotional, and physical effort that workers put into their jobs. Opportunities for career growth, workplace flexibility, and leadership communication are important factors that influence employee engagement [19, 20] . In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has altered the dynamics of employee engagement, the [21] underscores the necessity of including staff members at all levels in order to achieve sustained success [22] .

According to [23] projections, there would be a 34% reduction in overall engagement by 2024, highlighting the need for proactive engagement measures. Various advantages come with engagement, including enhanced productivity, decreased burnout, and increased retention rates [24] . Organizational culture, job qualities, and leadership style are factors that impact employee engagement. While [4] emphasized the importance of leadership in fostering an engaging environment, [25] noted that job resources like autonomy and social support promote engagement. Higher levels of engagement were positively correlated with improved profitability, productivity, and customer loyalty, according to [2] . [26] noted that high levels of engagement might result in a 19% increase in operational income.

It can be difficult to maintain engagement because of things like poor organizational practices, a lack of opportunity for career growth, and stress at workplace [27] . Maintaining high levels of engagement requires dramatic balance between job demands and sufficient resources.

-

[18] foundational theory of engagement emphasized the role of psychological meaningfulness, safety, and availability, which align conceptually with the variables used in this study: job satisfaction, environment satisfaction, and work-life balance. Similarly, the JD-R model [27] identifies these factors as essential job resources that drive engagement. Thus, the variables selected for clustering in this study are theoretically grounded in engagement literature and serve as quantifiable proxies for abstract psychological constructs.

-

2.2 Machine Learning

-

2.3 Enhancing Employee Engagement through Machine Learning

Through data-driven decision-making, machine learning (ML) employs algorithms that enable computers to carry out tasks based on patterns and inference rather than explicit instructions, revolutionizing industries including marketing, banking, and healthcare. ML can analyse large datasets to discover patterns in employee engagement that can be overlooked, improving understanding of employee behaviour and engagement levels [28] . Advances in machine learning have led to better forecasts of worker happiness, productivity, and turnover.

ML can be divided into three categories: supervised learning (training models on labeled data), unsupervised learning (using unlabeled data), and reinforcement learning (learning the best course of action via trial and error) [29 31] . Predictive analytics, customer segmentation, and process automation are three business applications of machine learning [32] . On the other hand, issues with interpretability, algorithmic bias, and data quality continue to exist [33, 34] .

Among various clustering techniques including hierarchical clustering and density-based methods such as DBSCAN k-means clustering was selected for this study due to its simplicity, scalability to large datasets, and successful application in prior HR and employee engagement research [35, 36] . Compared to more complex algorithms, k-means offers clear and interpretable groupings, making it highly suitable for integration into organizational decisionmaking frameworks. Its balance of computational efficiency and practical interpretability enables HR professionals to draw actionable insights for targeted interventions.

An unsupervised machine learning approach called k-means clustering is useful for employee engagement analysis since it divides data into clusters efficiently. [37] identified distinct workforce groups for targeted strategies by applying k-means clustering on engagement data from public university. [38] demonstrated the essential for advanced HR analytics by combining data mining and machine learning clustering to forecast employee turnover in the tech sector. [39] examined how ML has transformed HRM while raising concerns regarding bias and data quality.

In their analysis of employee satisfaction, [35] combined k-means clustering with association rules and decision trees, creating data-driven HR practices. [40] introduced a framework aimed at integrating sustainability into human resource management (HRM), focusing on employee wellbeing and performance enhancement. [36] employed machine learning (ML) to examine the engagement levels of Generation Z, emphasizing the importance of flexible work schedules and digital integration. [41, 42] enhanced the accuracy of turnover predictions by applying k-means clustering combined with PCA and decision trees.

By implementing targeted strategies and leveraging machine learning (ML) alongside k-means clustering, there is significant potential to boost employee engagement. However, to realize these benefits, challenges related to bias, interpretation, and data quality need to be addressed.

While existing research has frequently applied ML to predict employee turnover [38, 11] or analyse satisfaction patterns [35] , relatively few have utilized unsupervised learning to uncover latent engagement profiles without relying on predefined class labels. Most prior studies have favoured supervised learning techniques such as decision trees and logistic regression [42, 9] which depend on labeled outcome variables. This approach tends to reduce engagement to binary classifications (e.g., attrition vs. retention), oversimplifying its inherently multidimensional nature.

In addition, many studies rely on small or demographically homogeneous samples, limiting the generalizability of their findings. Demographic variability such as differences in age, gender, role, or department is often underexplored. Furthermore, methodological limitations such as overfitting, data imbalance, and inadequate discussion of model interpretability from an HR decision-making perspective remain unaddressed in much of the literature.

A critical gap in the existing body of work is the absence of integrative frameworks that bridge machine learning techniques with foundational theories of organizational behaviour. This disconnect often results in technically sound but theoretically shallow analyses. Moreover, the lack of robust cluster validation, replication across diverse organizational contexts, and reflection on the ethical and practical implications of algorithmic workforce segmentation limits the applicability of such models in real-world HR practices.

3. Need for the Study

Employee engagement plays a crucial role in driving productivity, innovation, and overall success in today’s competitive business landscape. Despite its importance, traditional approaches such as statistical analyses or surveybased assessments often yield generalized insights and fail to capture the diversity of experiences within the workforce. These methods typically overlook the potential for segmenting employees into distinct, actionable engagement profiles, thereby limiting the precision and effectiveness of HR interventions.

A notable gap exists in the application of unsupervised machine learning techniques, particularly k-means clustering, to uncover latent patterns in employee engagement. Without such segmentation, organizations risk implementing one-size-fits-all strategies that may not resonate with different workforce segments. The emergence of machine learning (ML) presents new opportunities for more sophisticated, data-driven insights into the complexities of employee engagement.

This study aims to leverage machine learning techniques, such as k-means clustering, to uncover distinct patterns and profiles of employee engagement. By utilizing ML, the study seeks to bridge knowledge gaps and provide actionable insights that improve retention, satisfaction, and performance, all while fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement.

4. Objectives

• To investigate how k-means clustering can be used to identify engagement patterns in employee survey data.

• To explore how effective machine learning is in segmenting the workforce for targeted interventions.

• To examine the effects of data-driven HR practices on employee engagement, satisfaction, and overall industry performance.

• To analyse the role of machine learning in predicting employee behaviour and reducing attrition rates.

• To offer practical recommendations for HR professionals on implementing machine learning to improve

5. Hypotheses

6. Methodology

6.1 Research Design and Approach

engagement strategies.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Distinct clusters of employees will emerge from k-means clustering based on job satisfaction, work-life balance, and environment satisfaction, and these clusters will differ significantly in their demographic and organizational profiles (e.g., age, department, marital status).

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The clusters identified through k-means will exhibit statistically significant differences in employee engagement scores, validating the algorithm's effectiveness in distinguishing meaningful subgroups.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Employee clusters characterized by low job and environment satisfaction will have significantly higher predicted attrition risk, as measured by logistic regression or alternative classification models.

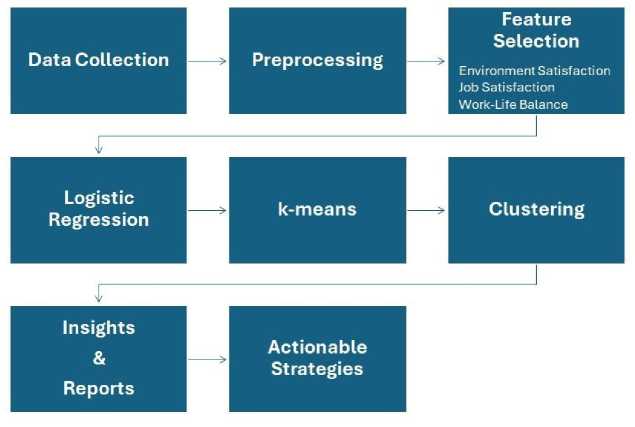

This study adopts a quantitative research design using unsupervised and supervised machine learning techniques to explore latent employee engagement patterns and predict attrition outcomes. The core objective is to utilize k-means clustering for identifying engagement profiles within a workforce and logistic regression for assessing the relationship between these profiles and attrition likelihood. The methodology prioritizes interpretability to ensure practical relevance for HR decision-making.

Fig. 1. Methodology for the Study

-

6.2 Dataset and Participants

-

6.3 Data Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study was derived from an organizational employee engagement survey consisting of 4,410 responses. The data included key variables related to engagement such as work-life balance, job satisfaction, and environment satisfaction, along with demographic information such as gender, department, and tenure. The gender distribution was imbalanced (60% male), which was preserved to reflect the real organizational structure, but carefully considered during interpretation.

A thorough preprocessing phase was conducted to ensure data quality and consistency:

-

• Missing values in numerical fields were treated using mean imputation.

-

• Outliers were identified using Z-score thresholds (|Z| > 3) and removed to prevent distortion in clustering outcomes.

-

• Feature scaling was performed using Min-Max normalization to standardize values between 0 and 1 for equal weighting in clustering.

-

6.4 K-Means Clustering

-

6.5 Cluster Interpretation

-

6.6 Attrition Prediction with Logistic Regression

Three continuous engagement variables Work-Life Balance, Job Satisfaction, and Environment Satisfaction were selected for clustering based on theoretical relevance and availability across all records. Categorical variables were excluded from the clustering input but later used for cluster interpretation.

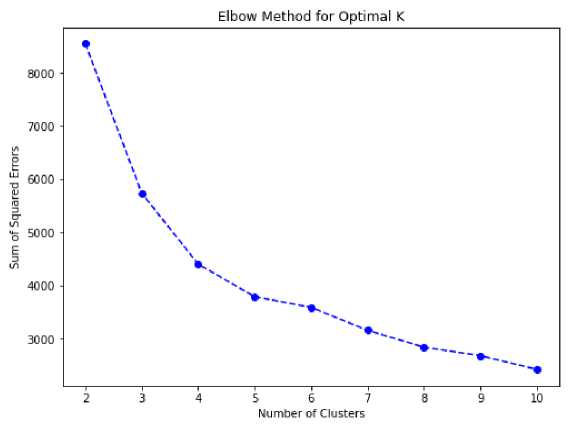

K-means clustering was employed to identify latent engagement patterns among employees. The algorithm was chosen for its balance of computational efficiency, interpretability, and scalability to large datasets. The optimal number of clusters (K = 4) was determined using the Elbow Method, which plots the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS) against different values of K.

To minimize sensitivity to initial centroid placement, k-means was executed with multiple initializations (n_init = 10), and the solution with the lowest WCSS was selected. While k-means assumes spherical, equally sized clusters an idealized assumption it was deemed suitable due to the standardized nature of the input features.

After clustering, excluded demographic and categorical variables (e.g., gender, job role, department) were reintroduced to describe and interpret each engagement cluster. These insights were used to explore meaningful differences across employee segments and inform HR intervention strategies.

To examine the relationship between engagement clusters and attrition, logistic regression was employed. Cluster assignments and engagement-related variables were used as predictors. Logistic regression was chosen for its simplicity, transparency, and ease of interpretation, making it ideal for HR practitioners seeking actionable insights.

Given the class imbalance in the attrition variable (i.e., few employees were labeled as attrition cases), model evaluation focused on:

• Precision: Correctness of predicted attrition cases

• Recall (Sensitivity): Ability to identify actual attrition cases

• F1-Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both metrics

7. Results and Discussion7.1 Demographic Factor Analysis

7.2 Clustering Analysis

These evaluation metrics are particularly suitable in imbalanced classification problems where traditional accuracy can be misleading.

By examining demographic data and clustering results to determine distinct workforce profiles, this study shows how successful k-means clustering is in analysing and improving employee engagement. The study examined 4,410 observations, focusing on key factors such as work-life balance, job satisfaction, and environment satisfaction. It found four distinct clusters. An analysis of variances between clusters using ANOVA was conducted, and employee behaviour and attrition rates were analysed using logistic regression as predictors. The thorough analysis provides practical insights to HR managers and organizational leaders by highlighting the benefits and drawbacks of data-driven HR strategies.

Table 1. Demographic Factors’ Distribution

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

20-30 |

927 |

21.27% |

|

31-40 |

1917 |

43.47% |

|

41-50 |

1047 |

24.02% |

|

51-60 |

504 |

11.56% |

|

61-70 |

15 |

0.34% |

|

Male |

2646 |

60.00% |

|

Female |

1764 |

40.00% |

|

Research & Development |

2883 |

65.37% |

|

Sales |

1338 |

30.34% |

|

Human Resources |

189 |

4.29% |

|

Married |

2019 |

45.78% |

|

Single |

1410 |

31.97% |

|

Divorced |

981 |

22.24% |

|

Sales Executive |

978 |

22.18% |

|

Research Scientist |

876 |

19.86% |

|

Laboratory Technician |

777 |

17.62% |

|

Manufacturing Director |

435 |

9.86% |

|

Healthcare Representative |

393 |

8.91% |

|

Manager |

306 |

6.94% |

|

Sales Representative |

249 |

5.65% |

|

Research Director |

240 |

5.44% |

|

Human Resources |

156 |

3.54% |

Table 1 indicates that Sales Executives (22.18%) and Research Scientists (19.86%) are the most common job roles. To enhance the engagement, strategies should be tailored to these positions. Sales Executives would benefit from performance-based rewards and advanced sales training, while Research Scientists require funding and collaborative research projects. By addressing the specific requirements of these roles, organizations can create a supportive work environment that enhances engagement and productivity.

The demographic analysis of age, gender, department, marital status, and job roles is crucial for interpreting k-means clustering results. It helps explain variations in satisfaction and work-life balance within clusters, as factors like age groups and job roles can influence engagement profiles. Marital status and department distribution also link descriptive statistics to clustering outcomes, making the analysis both data-driven and contextually relevant for developing targeted employee engagement strategies.

Fig. 2. Elbow Method for Optimal K Graph

The Elbow Method graph (Fig.2) helps determine the optimal number of clusters in k-means clustering. The X-axis shows the number of clusters, and the Y-axis represents the sum of squared errors (SSE), indicating how closely points are grouped around their centroids. Initially, SSE decreases as clusters increase, but eventually, the decrease becomes marginal, marking the “elbow” point. In this graph, the elbow occurs at four clusters, suggesting this configuration best represents the dataset. Hypothesis 1, which anticipated that k-means clustering would reveal distinct engagement patterns, was confirmed. The analysis using the Elbow Method showed that four clusters effectively captured the dataset’s structure, with further increases in clusters offering minimal improvement.

Table 2. K-Means Clustering

|

Environment Satisfaction |

Job Satisfaction |

Work Life Balance |

|||||

|

Std |

Std |

Std |

|||||

|

Mean |

Mean |

Mean |

|||||

|

0 |

1.49 |

0.50 |

3.48 |

0.50 |

2.71 |

0.70 |

1077 |

|

1 |

3.50 |

0.50 |

3.52 |

0.50 |

2.78 |

0.71 |

1613 |

|

2 |

1.54 |

0.50 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

2.75 |

0.73 |

649 |

|

3 |

3.49 |

0.50 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

2.78 |

0.70 |

1071 |

The k-means clustering analysis (Table 2) identifies four distinct clusters. Cluster 0, called “The Discontented,” includes 1,077 observations with high Environment Satisfaction (Mean = 1.49) but moderate Job Satisfaction (Mean = 3.48) and Work-Life Balance (Mean = 2.71), indicating overall dissatisfaction despite a favourable work environment.

Cluster 1, “The Unsettled,” is the largest with 1,613 observations, showing high Environment Satisfaction (Mean = 3.50) and Job Satisfaction (Mean = 3.52) but moderate Work-Life Balance (Mean = 2.78), indicating a need for better workplace conditions. Cluster 2, “The Harmonizers,” includes 649 observations with high Environment and Job Satisfaction (Means = 1.54 and 1.50, respectively) and moderate Work-Life Balance (Mean = 2.75), reflecting overall contentment. Cluster 3, “The Strugglers,” with 1,071 observations, has low scores across all categories, highlighting significant challenges. These findings validate Hypotheses 1 and 2, demonstrating the clustering algorithm’s effectiveness in identifying distinct engagement clusters and informing targeted strategies for improving employee wellbeing and organizational performance.

Table 3. ANOVA between the Clusters

Variable F-value P-value

Environment Satisfaction 5528.760

Job Satisfaction 5644.20

Work Life Balance 2.360.069

The ANOVA results (Table 3) show significant differences in Environment Satisfaction and Job Satisfaction among clusters, with F-values of 5528.76 and 5644.2 and p-values of 0 for both, indicating significant variation due to the clustering process. In contrast, the F-value for Work-Life Balance is 2.36 with a p-value of 0.069, suggesting no significant differences across clusters for this variable. These results emphasize the importance of Environment and Job Satisfaction in distinguishing clusters, while noting some potential variability in Work-Life Balance.

These ANOVA results support Hypothesis 3 (H3), which suggests that datadriven HR practices like k-means clustering lead to higher employee engagement, satisfaction, and overall organizational performance. Significant differences in Environment and Job Satisfaction across clusters (F-values of 5528.76 and 5644.2, p-values = 0) indicate that clustering effectively identifies distinct engagement profiles. Although Work-Life Balance scores show slight variability (F-value = 2.36, p-value = 0.069), the results highlight the importance of consid ering multiple engagement dimensions. Overall, k-means clustering proves valuable for enhancing employee satisfaction and engagement through data-driven HR strategies.

Table 4. Logistic Regression regarding Attrition and Clusters - Model Performance Metrics

|

Attrition |

No (Count: 741) |

Yes (Count: 141) |

Overall (Count: 882) |

|

Precision |

0.84 |

0 |

0.71 |

|

Recall |

1 |

0 |

0.84 |

|

F1-Score |

0.91 |

0 |

0.77 |

|

Support |

741 |

141 |

882 |

As presented in Table 4, the logistic regression model was used to predict employee attrition based on the clusters derived from the k-means analysis. The dataset comprised 882 observations, including both attrition and non-attrition cases.

The model demonstrated strong performance in identifying non-attrition cases, with a precision of 0.84, recall of 1.0, and an F1-score of 0.91, indicating high accuracy in predicting employees who are likely to stay. However, for attrition cases, the model yielded zero scores for precision, recall, and F1-score. This outcome indicates that the model failed to identify any attrition cases, likely due to the lack of positive predictions for the minority class.

The overall performance metrics precision = 0.71, recall = 0.84, and F1-score = 0.77 reflect a reasonably satisfactory model in the broader context but emphasize a significant shortcoming in identifying actual attrition. This issue is common in datasets with high class imbalance, where the minority class (in this case, attrition) is underrepresented, resulting in poor recall and low sensitivity for that group.

These results underscore the importance of using recall and F1-score over simple accuracy metrics in imbalanced classification settings. While the model correctly identified most non-attrition instances, it completely failed to detect true attrition events, rendering it ineffective for predictive decision-making regarding employee turnover.

The results provide partial support for Hypothesis 3 (H3), which posited that data-driven HR practices such as k-means clustering would lead to improved engagement and satisfaction outcomes. The clusters were useful for identifying employee groups more likely to remain with the organization, as reflected in the high performance for nonattrition predictions. However, the model’s inability to identify attrition cases limits its utility for proactive turnover management. This indicates that while clustering is valuable for descriptive segmentation, more advanced predictive techniques may be necessary for addressing complex classification problems like attrition forecasting.

This study acknowledges several methodological limitations that may influence the interpretation and generalizability of its findings. One of the primary concerns is the class imbalance within the attrition data. While logistic regression performed well in predicting non-attrition cases, it entirely failed to identify any actual attrition instances. This issue is common in imbalanced datasets, where the minority class employees who left the organization is underrepresented. As a result, the model exhibited zero recall and precision for attrition cases, limiting its usefulness in turnover prediction. Relying on overall accuracy in such scenarios can be misleading. Future research should consider implementing advanced classification techniques such as random forests, support vector machines, or ensemble methods, combined with class-balancing strategies like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) or costsensitive learning, to improve the identification of minority class outcomes.

Another significant limitation is the gender imbalance within the dataset, with 60% of the respondents being male. Such demographic skew may affect the formation and interpretation of engagement clusters. If engagement drivers differ significantly by gender for example, if female employees have distinct expectations regarding work-life balance or face unique challenges related to leadership support the clustering results may not accurately capture their perspectives. This underrepresentation risks oversimplifying or misrepresenting key engagement dynamics and raises concerns about the generalizability of findings to more gender-diverse or balanced workforces. Future studies could address this limitation through stratified sampling or gender-specific cluster analysis to uncover nuanced patterns.

A further limitation involves the lack of external validation of the clustering results. The study was conducted using data from a single organization, which may have specific cultural, structural, or operational characteristics influencing the results. Without applying the clustering framework to external datasets from other organizations or industries, it is difficult to assess the stability, consistency, and generalizability of the identified engagement profiles. Incorporating cross-validation techniques or testing the clustering model on benchmark datasets in future research could strengthen confidence in its applicability across diverse organizational contexts.

Lastly, while k-means clustering offers simplicity, scalability, and interpretability, it comes with technical constraints that impact the analysis. The algorithm assumes spherical and equally sized clusters, which may not reflect the true distribution of engagement subgroups in complex organizational environments. It also requires the prespecification of the number of clusters (K), typically based on heuristics like the Elbow Method, which can be subjective or inconclusive. Furthermore, k-means is sensitive to initial centroid placement, which can yield different clustering outcomes across runs. Although this study mitigated the issue through multiple initializations (n_init = 10), variability remains a concern. Future work could explore alternative clustering methods such as DBSCAN, Gaussian Mixture Models, or hierarchical clustering, which may offer greater flexibility and robustness.

-

7.3 Practical Applications and Implementation Considerations

-

7.4 Organizational Context Considerations

The k-means clustering results provide meaningful and actionable segmentation of the workforce based on key engagement dimensions. From a practical perspective, Human Resource (HR) professionals can leverage these insights to design targeted, evidence-based interventions rather than relying on generalized engagement strategies. For instance, Cluster 3, labeled as “The Strugglers”, may benefit from interventions focused on job enrichment, mental health resources, or stress reduction programs. Similarly, Cluster 1, referred to as “The Unsettled”, could be supported through work-life balance reforms, managerial coaching, or flexible work arrangements. These tailored approaches are more likely to yield higher return on investment (ROI) and measurable improvements in engagement, satisfaction, and retention compared to one-size-fits-all programs.

Despite these benefits, the integration of machine learning tools particularly unsupervised models like k-means clustering into HR decision-making processes presents several challenges. First, many HR departments lack the technical expertise required to develop, interpret, or deploy clustering algorithms. This skills gap can result in poor implementation or misinterpretation of results. Second, unsupervised models are often perceived as “black boxes”, especially when stakeholders cannot easily visualize how clusters are formed or what they signify. This can hinder trust and limit the adoption of insights.

Third, the use of employee data for algorithmic decision-making raises ethical and privacy concerns. Organizations must implement strong data governance policies and maintain transparency in how data is collected, processed, and used. Without clearly communicating the intent and scope of ML applications, organizations risk damaging employee trust. Finally, even the most accurate and insightful machine learning models may be underutilized if their outputs are not translated into HR-relevant language. Actionability requires that insights be embedded into existing HR frameworks, such as performance reviews, training needs assessments, or workforce planning tools.

To overcome these challenges, organizations are encouraged to establish hybrid teams that combine the expertise of data scientists and HR analysts. Investing in model explainability tools, such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) particularly for supervised models can increase stakeholder confidence and transparency. In the case of unsupervised models, clear documentation of clustering logic and variable importance is essential. Additionally, organizations may begin with pilot initiatives using clusterbased insights in low-risk areas (e.g., wellness programs or feedback mechanisms), gradually scaling up successful interventions. Finally, integrating ML outputs into existing HR dashboards or enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems can enhance accessibility and decision-making, driving broader organizational acceptance and impact.

While the current study provides valuable insights into employee engagement through quantitative indicators such as job satisfaction, work-life balance, and environment satisfaction, it does not explicitly account for broader contextual organizational factors that may significantly influence these perceptions. Notably, leadership style such as transformational or supportive leadership has been consistently associated with engagement outcomes [25, 4] . Likewise, organizational culture, whether hierarchical, innovative, or inclusive, can shape how employees experience their work environment and satisfaction levels, often independent of individual-level metrics.

Additionally, work design elements such as autonomy, task variety, and role clarity are known to mediate the relationship between perceived satisfaction and actual engagement. By not incorporating these structural and cultural variables, the current clustering analysis may overlook latent systemic drivers of disengagement. For example, the emergence of a low-engagement group such as “The Strugglers” may reflect not only individual dissatisfaction but also deeper issues tied to departmental leadership styles, inequitable workloads, or organizational norms.

Future research should adopt a more holistic and multi-dimensional framework by integrating qualitative data (e.g., interviews, focus groups, or organizational diagnostics) and expanding survey instruments to capture variables related to leadership behaviors, organizational culture, and job design. This would facilitate a richer understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving engagement patterns and enhance the precision of resulting interventions. A mixed-methods approach would also bridge the gap between algorithmic insights and organizational context, thereby improving the interpretability and applicability of machine learning–based segmentation in HR decision-making.

8. Conclusion

This study employed a comprehensive analytical framework combining k-means clustering, ANOVA, and logistic regression to examine patterns in employee satisfaction, engagement, and attrition. The results revealed distinct engagement profiles, ranging from high to low satisfaction, with significant differences observed in job satisfaction and environment satisfaction across clusters. More subtle but important variations in work-life balance highlight the need for context-specific HR interventions that address its complex relationship with both engagement and retention.

The practical implications of these findings are substantial. For example, employees in clusters such as “The Discontented” and “The Strugglers” could benefit from targeted interventions, including job enrichment, skills training, mental health support, and performance feedback systems. Meanwhile, “The Unsettled” may respond better to workplace culture reform, managerial coaching, and flexible work arrangements. In contrast, “The Harmonizers”, who report high engagement, present an opportunity to reinforce existing best practices while monitoring for early signs of disengagement to prevent future attrition.

While the logistic regression model demonstrated strong predictive power for non-attrition cases, it struggled to identify actual attrition instances due to class imbalance, a common limitation in workforce datasets. This underscores the need for continuous employee monitoring, feedback systems, and early-warning indicators to support proactive retention strategies. Future research should address these limitations by exploring more robust classifiers such as decision trees, random forests, or gradient boosting algorithms, which can better handle imbalanced classes. Techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) or cost-sensitive learning could further enhance the prediction of rare attrition events, offering more actionable insights for HR teams.

Moreover, this study’s clustering outcomes, although insightful, were limited to a single organizational context. Future research should aim to validate these engagement clusters across diverse industries, geographic regions, and organizational sizes. The incorporation of external benchmarking data and the use of clustering performance metrics— such as the Silhouette Coefficient, Davies-Bouldin Index, or Calinski-Harabasz Score—would enhance the credibility and generalizability of findings.

To address the technical limitations of k-means, future studies should also consider applying more flexible clustering techniques such as DBSCAN, Gaussian Mixture Models, or hierarchical clustering, which do not assume spherical clusters or equal sizes. Hybrid or ensemble clustering approaches could also be explored to improve both cluster stability and interpretability, particularly in HR settings where nuanced subgroup identification is essential for targeted interventions.

Importantly, while this study provides a strong quantitative foundation for understanding employee engagement, it lacks integration of organizational contextual factors—such as leadership behaviors, cultural norms, or work process designs—that likely influence employee perceptions and behaviors. These contextual variables may interact with or moderate the relationships identified in the current analysis. Future research should adopt a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative data (e.g., interviews, focus groups, or ethnographic studies) and validated instruments (e.g., Denison’s Organizational Culture Survey, Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire) to offer a more holistic view of engagement dynamics.

Finally, while the study demonstrates that machine learning can uncover meaningful and actionable engagement patterns, translating these insights into organizational change requires thoughtful implementation. HR teams must prioritize interpretability, ethical data use, and staff training to ensure these tools are used responsibly and effectively. Collaborative efforts between HR professionals and data scientists will be critical to operationalize these findings and drive data-informed organizational development.

-

8.1 Theoretical Contributions

The findings illustrate the value of unsupervised machine learning algorithms in revealing hidden structures within employee data structures that traditional survey analyses may overlook. These insights support the idea that employee engagement is multidimensional, and that homogenized survey scores may mask important subgroup differences. The use of k-means clustering provided a framework for identifying distinct engagement profiles, which can inform tailored interventions, thereby demonstrating the real-world utility of quantitative segmentation grounded in theory.

Importantly, this study aligns with and extends the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, which posits that employee engagement is influenced by the balance between job demands and available resources. The clustering analysis identified groups such as “The Strugglers” characterized by low job and environmental satisfaction and “The Harmonizers”, who exhibit high satisfaction across all measured dimensions. These empirical patterns reflect varying levels of resource adequacy and psychological strain, thereby offering a theory-informed interpretation of data-driven findings. In this way, the study demonstrates how advanced analytics can operationalize established theoretical frameworks, providing practical segmentation that aligns with engagement theory.

Furthermore, the research supports engagement theories that advocate for personalized strategies rather than generalized approaches. By revealing meaningful variation in job satisfaction, environment satisfaction, and work-life balance, the study underscores the importance of targeted interventions a core tenet in modern engagement theory. The integration of organizational behavior theory and machine learning thus represents a novel contribution to the literature, bridging traditionally qualitative frameworks with quantitative, scalable methodologies.

In sum, this study provides a conceptual and empirical bridge between organizational psychology and machine learning, illustrating how unsupervised clustering techniques can support theory-informed HR decision-making. It sets a foundation for future research that combines behavioral theory, engagement modeling, and predictive analytics to advance the strategic capabilities of HR functions.