Ethnic and confessional factors of comfort of the urban space in the Russian Arctic

Автор: Ilya F. Vereschagin, Anton M. Maksimov

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 34, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article deals with the influence of the ethnic and religious structure of the population of large cities of the Russian Arctic on the comfort of the urban space. The authors highlight the basic requirements for the urban area by social groups, based on their ethnic and religious affiliation. The main urban objects and spaces naturally and historically created for the needs of ethnic and religious groups are determined. The study used methods of social mapping, observation, analysis of statistical data. On the example of large cities in the regions of the Russian Arctic, the authors show the unsystematic nature of meeting ethnic and religious needs in the creation of comfortable urban space. According to the authors, this is primarily due to the diverse history of urban settlements in the Arctic zone, as well as the functional purpose of settlements, which differ in number and composition of residents. Based on this differentiation, the corresponding types of urban settlements are distinguished. Based on the relatively successful example of the policy of the capital region, the article makes recommendations for improving the proper administration of the urban municipalities of the Russian Arctic. Attention is drawn to the possible features of such a policy, considering the specifics of the Arctic cities and migration processes taking place in the region.

Ethno-cultural diversity, ethno-confessional composition of the population, the comfort of the urban space, the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318492

IDR: 148318492 | УДК: [323.1:316.334.56](985)(045) | DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2019.34.110

Текст научной статьи Ethnic and confessional factors of comfort of the urban space in the Russian Arctic

The formation of comfortable urban space is now a very relevant topic. The town dweller fills himself in the post-industrial era and understands that his space cannot be formed only from residential, commercial and industrial zones. He has a lot of needs, incl. spiritual ones that he would like to meet in the urban space. The administration of the municipality must also understand this, not to make mistakes in the implementation of its management activities. It must communicate with the urban community to know how to develop the urban landscape. But it would be mistaken to be limited to roads and park areas — the comfort of urban space is influenced by many factors, including ethnic-confessional nature.

Religious buildings initially determined the logic of the development of the urban settlement. According to G.L. Golts, “the creation of a network of temple structures in the regions and large spatial-cultural communities of people <...> played an important role in the development of urbanized structures, the appearance of which brought to life the patterns of their functioning” [1, Golts G.L., p. 49]. Domestic cities suffered partly in architectural terms from the Soviet era (alt-

∗ For citation:

hough they were largely acquired): many places of worship were destroyed or redeveloped. In the past decade, they have been restored. It is important because “the heritage carries the cultural and civilizational codes of the nation; it bases on the identity of both individual urban societies and the nation; the loss of heritage inevitably leads to the fact that society loses its support and roots, without which no development is possible ”[2, Gorodkov A.V., p. 10]. Shepelev N.P., Shumilov M.S. noted that “modern town planners do not have experience in building systems of religious buildings, and simply transferring previous experience and traditions will not always be able to give positive results in terms of the functioning of a modern high-rise town and buildings rushing up” [3, Shepelev N.P. ., Shumilov M.S., p. 23]. The authors believed that it was necessary to develop programs for urban religious systems, considering the choice of location and room capacity. In this regard, town planners and municipalities should be guided by the opinion of the leaders of ethnicconfessional groups, who should develop their documents of recommendatory and methodological nature. Kataeva Yu.V. draws attention to the fact that due to unregulated migration and changes in the ethnic-social composition of citizens, there are problems of coexistence of representatives of ethnic groups, the interaction of ethnonational cultures and settling religious differences [4, Kataeva Yu.V., p. 133]. These problems should be solved at the municipality level. Kopy-tova Y.K. believes that “the basis of urban planning should be the idea of multiculturalism, which allows to reduce social tension and ensure the integration of the visiting population into the town” [5, Kopytova Ya.K., p. 45]. Probably, this should be expressed in the creation of ethnocultural objects in the urban environment.

But the government does not seek to clarify the policies of municipalities regarding the ethnic-confessional factors of the comfort of urban space. According to the Code of Rules SP 42.13330.2011 “Urban planning. Planning and development of urban and rural settlements”, adopted by the Ministry of Regional Development of the Russian Federation, the planning structure of urban settlements should be formed, providing, among other things, “a comprehensive accounting of architectural and town-planning traditions, climatic, historical-cultural, ethnographic and other local features.”1 The document states that religious buildings can be in residential and public business areas. In the annex to the rules — “Standards for calculating institutions and service enterprises and the size of their land plots,” the category “Institutes of religious purposes” is indicated, while this refers exclusively to Orthodox institutions: 7.5 churches per 1,000 Orthodox believers; accommodation involves coordination with the local diocese. But in general, the rules do not say anything about ethnic-confessional institutions in the urban environment.

The federal priority project “Formation of a comfortable urban environment” 2017–2020 does not consider ethnic-confessional factors of comfort. It discusses necessary and priority measures, e.g., improvement of yard areas, development of mass recreation places, the arrange- ment of infrastructure facilities for accessibility of the urban environment among people with limited mobility, creation of sports infrastructure, improvement of popular trade zones, etc.2 Ethnoconfessional objects can be approached only under the event "the formation of the cultural value (identity) of the town." But in general, the government does not pay attention to such factors, while leaving a wide field for the possibilities at the regional level. We cannot fail to recognize that officially our state is free from preferences both in ethnonational and confessional terms, and all ethnic groups and denominations are equidistant from it. However, still, in our opinion, to preserve interethnic and inter-religious peace, it is necessary to keep in mind ethnic-confessional factors in the management of municipalities.

Today, a crucial issue of the comfort of urban space is being raised in the Arctic towns in connection with a no less relevant topic of development of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation. Researchers point out the uneven economic development of the Russian Arctic. The Russian Arctic has a mono-profile resource-raw economy, contrast of the western and eastern sectors. But at the same time, the Arctic territories are not deprived of innovative possibilities [6, Zaikov K.S., Kalinina M.R., Kondratov N.A., Tamitskii A.M.]. However, the Arctic territories (especially their cities) are severely affected by migration.

On the one hand, immigration from other territories (from the post-Soviet areas as well) is to those areas that are economically attractive (e.g., the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District). But on the other hand, the youth of the Arctic often does not seek to link their future with their native area. For the western sector of the Russian Arctic, this is more typical than for the eastern sector [7, Zai-kov K.S., Katorin I.V., Tamitskii A.M., p. 236].

Of course, serious attention is paid today to the ethnic-confessional situation in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation. The state pursues a multifaceted policy in the Arctic, affecting the preservation of inter-ethnic peace, a special relationship to indigenous minorities, support for four traditional religions of Russia (Orthodoxy, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism), and migration policy [8, Zaikov K., Tamitskiy A., Zadorin M.]. But at the beginning of the article, we should discuss an important point, namely the difficulty of determining the ethnic-confessional composition of the town in the Russian Arctic. First, we have data on the ethnic composition of the constituent entities of the Russian Federation due to the 2010 All-Russian Population Census and various ethnic-sociological studies. But in both cases, the ethnic identification of the individual occurs from his/her words, and it brings a certain proportion of convention into the statistics. E.g., children and even grandchildren from inter-ethnic marriages, which were enough in the Soviet times in the Arctic, cannot be unambiguously assigned to an ethnic group; they identify themselves with more attractive ethnicity. Secondly, severe emigration flows, and immigration should be considered, incl. those not fixed by statistics and research. Temporary and seasonal migrations also affect ethnonational composition.

However, we must base on official data, e.g., the dynamics of the ethnonational structure of the population of the Russian Arctic traced by F. Kh. Sokolova [9]. The census of 2010 gives us an idea of the size of the largest ethnic groups and the share of the urban population in each territory of the Russian Arctic (Table 1). At the same time, as a rule, representatives of indigenous minorities of the Far North, Siberia, and the Far East do not live in towns.

Table 1

The population size of the most numerous ethnic groups by territories of the Russian Arctic and the share of the urban population according to the 2010 census 3

|

The Murmansk Oblast |

The Republic of Karelia |

The Ar-khan-gelsk Oblast |

Nenets AD |

The Komi Republic |

Yamal-Nenets AD |

Krasnoyarsk Krai |

The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) |

Chu-kotsky AD |

|

|

Azerbaijanis |

3,841 |

1,793 |

2,605 |

157 |

4,858 |

9,291 |

16,341 |

2,040 |

107 |

|

Bashkirs |

914 |

162 |

394 |

49 |

2,333 |

8,297 |

2,955 |

1,819 |

125 |

|

Belarusians |

12,050 |

23,345 |

5,810 |

283 |

8,859 |

6,480 |

9,900 |

2,527 |

364 |

|

Veps |

82 |

3423 |

18 |

- |

23 |

3 |

7 |

4 |

- |

|

Karels |

1,376 |

45,570 |

180 |

2 |

180 |

23 |

68 |

17 |

3 |

|

Komi |

1,649 |

182 |

4,583 |

3623 |

202,348 |

5,141 |

159 |

32 |

7 |

|

Komi-Izhemtsy |

472 |

- |

1 |

1 |

5,725 |

108 |

3 |

- |

- |

|

Germans |

725 |

490 |

848 |

10 |

5,441 |

22,363 |

1,540 |

108 |

|

|

Nenets |

149 |

4 |

8020 |

7504 |

503 |

29772 |

3,633 |

23 |

22 |

|

Russians |

642,310 |

50,7654 |

1,148,82 1 |

26648 |

555,963 |

312,01 9 |

2,490,730 |

353,649 |

25,068 |

|

Tatars |

5,624 |

1888 |

2,335 |

209 |

10,779 |

28509 |

34,828 |

8122 |

451 |

|

Ukrainians |

34,268 |

12,677 |

16,976 |

987 |

36,082 |

48985 |

38,012 |

20341 |

2,869 |

|

Finns |

273 |

8,577 |

69 |

- |

112 |

78 |

303 |

126 |

1 |

|

Khanty |

9 |

6 |

9 |

1 |

48 |

9489 |

14 |

5 |

1 |

|

Chuvansy |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

3 |

897 |

|

|

Chuvashi |

1,782 |

867 |

1,357 |

75 |

5,077 |

3,471 |

11,036 |

123 |

166 |

|

Chukchi |

3 |

3 |

1 |

- |

2 |

2 |

9 |

670 |

12,772 |

|

Evenki |

5 |

2 |

14 |

13 |

6 |

42 |

4,372 |

21,008 |

18 |

|

Eveny |

3 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

27 |

15,071 |

1,392 |

|

Eskimos |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

11 |

1,529 |

|

Yakuts |

16 |

15 |

18 |

3 |

15 |

10 |

1468 |

466,492 |

62 |

|

Urban population (%) |

92.8 |

78 |

75.7 |

67.8 |

76.9 |

84.7 |

76.3 |

64.1 |

64.8 |

With the definition of confessional composition, the situation is even more complicated. The 2010 all-Russian census did not include the issue of confessional affiliation; therefore, it is possible to argue about the confessional composition only based on sociological research. Personal research is periodically conducted in the territories; a nationally representative survey was conducted in 2012 by the request of the “Sreda” service, the Public Opinion Foundation. No more rel-

-

3 Vserossijskaya perepis' naseleniya 2010 goda. Tom 11-1. Sootnoshenie gorodskogo i sel'skogo naseleniya po sub"ektam Rossijskoj Federacii (v procentah k obshchej chislennosti naseleniya). Tom 11-4. CHislennost' nase-leniya naibolee mnogochislennyh nacional'nostej po sub"ektam Rossijskoj Federacii. [National Census of 2010. Volume 11-1. The ratio of the urban and rural population by territories of the Russian Federation (as a percentage of the total population). Volume 11-4. The population size of the most numerous nationalities by territories of the Russian Federa-tion].URL: http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/perepis2010/croc/perepis_itogi1612.htm (Accessed: 11 October 2018). [In Russian]

evant and extensive research in this area has been completed, but the survey did not cover the Nenets and Chukotka Autonomous Districts. The result is presented in table 2.

Table 2

Attitude to the faith of citizens by territories of the Russian Arctic (the most frequent answers, %) 4

|

The Murmansk Oblast |

The Republic of Karelia |

The Arkhange lsk Oblast |

Nenets AD |

The Komi Republi c |

Yamal-Nenets AD |

Krasnoya rsk Krai |

The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) |

|

|

ROC |

42 |

27 |

29 |

62.4 |

30 |

42 |

30 |

38 |

|

believe in God but do not profess a particular religion |

28 |

44 |

32 |

6.2 |

41 |

14 |

35 |

17 |

|

don't believe in god |

12 |

18 |

16 |

25.1 |

14 |

8 |

15 |

26 |

|

profess the traditional religion of their ancestors, worship the gods and the forces of nature |

<1 |

<1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

<1 |

13 |

|

Islam |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

1 |

18 |

<1 |

2 |

|

Protestantism |

<1 |

1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

Nevertheless, based on the figures of statistics, one can imagine the size of ethnic and confessional groups, which will make it possible to determine their needs of a ceremonial and cultural nature in an urban environment.

Ethnic and confessional requirements of a town

First, it is necessary to single out the ethnic-confessional requirements that determine the comfort of the urban space. And, to determine whether their application is possible in principle.

A believer who needs to implement some divine service practice, as a rule regularly, needs accommodation. Basically, in various confessions, worship is a public event in which all members of a religious community should take part. Therefore, this requires a separate architectural structure, which will accommodate all comers. In the case of religious holidays, it may be necessary not only to accommodate but also the territory adjacent to the church of a denomination (e.g., for religious processions). The object that attracts various believers can be not only a temple but also one or another symbol, a pendulum (e.g., a worship cross). Because of this, the question of how comfortable it will be for believing citizens to perform the necessary religious activities arises within the framework of urban space. It consists of at least two components: 1) how convenient is the object relative to the areas of residence (is it comfortable to reach it); 2) how convenient is the object relative to neighboring buildings (can you conduct rituals).

This question (and sub-questions) should be looked at not only from the position of the believer but also from the position of people who are not a part of a religious community (those of different faiths or atheists). The location of a cult structure close to other similar buildings can lead

-

4 Project “Sreda”. URL: http://sreda.org/arena (Accessed: 11 October 2018). [In Russian]; Nenets Autonomous Okrug. URL: http://smi.adm-nao.ru/otnosheniya-v-nao/sociologicheskoe-issledovanie-obshestvennogo-mneniya-po-voprosam-toler/ (Accessed: 11 October 2018). [In Russian]

to all sorts of misunderstandings and conflicts. Although in our country conflicts on religious grounds are extremely rare. But for a secular person who does not identify himself with a confession or faith, the presence of a religious building or religious symbol can be an annoying factor. The Orthodox procession of the cross, blocking the streets nearest to the temple, calls for prayers of Muslims announced to the surrounding neighborhoods, the toll of Christian churches or the public offering of sacrifices in Islam can all determine discomfort in the urban environment. Sometimes such irritation leads to hatred on religious grounds and the desecration of temples, as in Murmansk5, and demolition of monuments, as in Arkhangelsk 6.

Thus, the presence and location of the necessary confessional institutions and religious symbols, of course, is a factor in the comfort of urban space. The same can be said about not only temples or prayer rooms but also the location of the community. However, as a rule, in this case, we have in mind the address to which a religious organization is legally registered, and this is important not so much for believers as for the controlling authorities.

Another factor is the ability to practice their ethnonational traditions and customs. In the 21st century in a state of post-industrial society, a significant part of urbanized ethnic groups (Russians, Ukrainians, Tatars, and others) cease to need this. They are already in many ways part of a unified sociocultural space that began to form in the Soviet era. Ethnonational traditions are strong in rural areas, for example, among indigenous peoples. For town dwellers, due to a different lifestyle, the traditions of their people often remain within the framework of folklore. Sometimes a particular association of ethnos and denomination is held (e.g., Russian “means” Orthodox, Tatar — Muslim, Jew — Jew, etc.). Even a confession sometimes becomes a way of ethnic, rather than religious identification7; in this case, ethnic traditions are replaced by confessional. Because of this, the center of attraction of citizens seeking to realize their ethnonational traditions again becomes the temple of the corresponding denomination (church, mosque, synagogue, etc.). But apart from him, of course, it is necessary to single out various national centers (premises of national-cultural autonomies, diasporas, etc.) in which representatives of certain ethnic groups gather to maintain communication and preserve traditions. But, as a rule, these objects are in offices, in business buildings located in the town center. This situation cannot be called comfortably, but not every ethnonational association can afford a separate building. Therefore, it is logical that often the functions of such an institution are combined with religious services within the same building.

Also, various monuments and memorable places in the town refer to objects of ethnonational significance. It can be not only sculptures depicting famous life bearers but also ethnic ceme- teries. Unfortunately, such objects can also become annoying for foreigners. In the Arctic, xenophobia and conflicts on ethnic grounds are not typical, but still, exceptions, e.g., anti-Semitism, are possible. Thus, the satisfaction of ethnonational needs is also a factor in the comfort of urban space.

The administration of any town in its urban planning policy must consider these factors. In Russia, the openness of spatial movements of representatives of various ethnonational and confessional groups makes one think about the prospects for the development of the town. Renovation of old urban spaces should assume not only the construction of new residential or public business zones but also objects of religious and ritual purposes, based on the needs of citizens. Of course, this is not done at the expense of the municipality, territory or state. The same applies to new built-up areas space should be provided for the placement of ethnic-confessional objects. Competent administration monitors the mood of citizens, their ethnic and confessional composition of the districts of the town, and therefore it is ready for such challenges. In meeting the needs of ethnonational and confessional groups, the administration coordinates the construction policy with their legitimate representatives. E.g., requests of national-cultural autonomies should be satisfied by the administration as far as possible. The choice of the place of construction of religious buildings should also be made considering the opinion of the leaders of the respective denominations. It is through the communication of the municipal administration with ethnic-religious groups that one can succeed in the development of urban space.

One of the examples of Russian towns where ethnic-confessional needs are most successfully meeting within the urban environment is Moscow. The dynamically developing metropolis, where representatives of all the main denominations of Russia live, thought beforehand not only about the preservation and dissemination of park zones, laying of socially relevant communications, building magic centers, but also creating a whole network of religious institutions. In the towns, temples of Orthodox (incl. Old Believers), Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, and others are presented in different proportions. The Russian Orthodox Church is traditionally the largest religious association. It also owns a large-scale, ambitious project “Program-200” implemented by the Foundation “Support for the construction of churches in the city of Moscow” with the participation of the Government of Moscow. Under this program, it is planned to build two hundred new right-renowned churches on the territory of all districts of the city so that they are within the so-called walking distance (about 1 km). The construction fund is financed only by the charity. The Moscow mayor's office only allocates land plots for construction for free and helps with the construction of communications.

A similar project in 2010 was argued. In the early 1990s, in the capital, there were 254 temples and chapels, in 2000 — 519 (mainly due to the restoration of old ones)8. When creating the construction fund, Patriarch Kirill noted that to achieve an average value of temples for Russia

(11.2 thousand people per parish), 591 churches must be constructed in Moscow 9. But the program still proposed the construction of a little more than two hundred. It is supposed to put into operation ten churches a year, although in eight years only 45 were built under the program10.

The program caused fierce discussions about the need for such construction. At a minimum, because there is simply no reliable data on the number of church-related believers in Moscow (and indeed throughout Russia), and sociological polls often sin with discrepancies in figures. But even if we cannot assert that there are today a sufficient number of Orthodox in need of churches, it can be recognized that the ROC is proactive mainly, knowing that the Catechism of the population, carried out every day, should (in the sense of the target) lead to the same number of believers. However fierce discussions in Moscow more than once led to clashes over the construction of a temple in the middle of the park. The brightest example was in the park “Torfyanka” in 2015–201611.

Nevertheless, if we consider “Program-200” from the position of meeting religious needs, then we should recognize its positive effect. In the case of unconditional problems with the choice of places for construction, which causes controversy, the very idea of creating a network of Orthodox churches plays a positive role in creating a comfortable urban environment.

The situation is different with other confessions, which mostly resign to a small number of churches in Moscow. However, a significant problem is still the shortage of mosques in the city. Today there are five mosques in Moscow, but they belong to different Islamic organizations (the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of the Russian Federation, the Central Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Russia and the Shiites). The annual influx of migrants increases the need for these religious institutions. More than once during essential holidays, Muslims were forced to pray on the street, blocking movement. But even more significant irritation of the citizens caused a sacrifice in the streets12. In part, these problems were removed, incl. reconstruction Cathedral-Mosque in Moscow in 2011–2015. But it is quite likely that Moscow will soon need a program to build mosques, like the plan of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Thus, we see that Moscow is not an ideal city from the perspective of satisfying ethnicconfessional needs within the urban environment. However, there are actual processes that allow us to compare such a situation in the towns of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation of interest to us.

Towns of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation

The modern ethnocultural space of the Russian Arctic includes representatives of more than one hundred ethnic groups with different beliefs and traditions. In addition to the size and composition of the indigenous peoples in these territories, one should consider the dynamics of migration of representatives of various ethnic groups to the most attractive, dynamically developing territories (Nenets and Yamal-Nenets ADs, the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) and the Krasnoyarsk Territory). Representatives of indigenous minorities mainly live in rural areas (82.2%), and in the towns, the new settlement population is concentrated [10, Ethnonational, pp. 84–85, 122]. Recently, there has been a tendency of growth in the number of immigrants from Central Asia and the Transcaucasus, which, of course, in the future may change the socio-cultural space of towns. Nearly 2 million people live in towns and urban-type settlements of the Russian Arctic (89.3%), and about 250,000 people (10.7%) live in rural areas [11, Fauzer V.V., Lytkina T.S., Fouser G.N., p.

-

128 ]. Such a geodemographic situation is understandable — in the challenging conditions of the Far North, and with the traditional way of life of a significant part of the representatives of the in-

- digenous people, the population could not but concentrate in the towns. At the same time, of course, the construction and development of towns in the Arctic zone are influenced by various factors: geographical location, climatic conditions, the natural resource potential of the adjacent

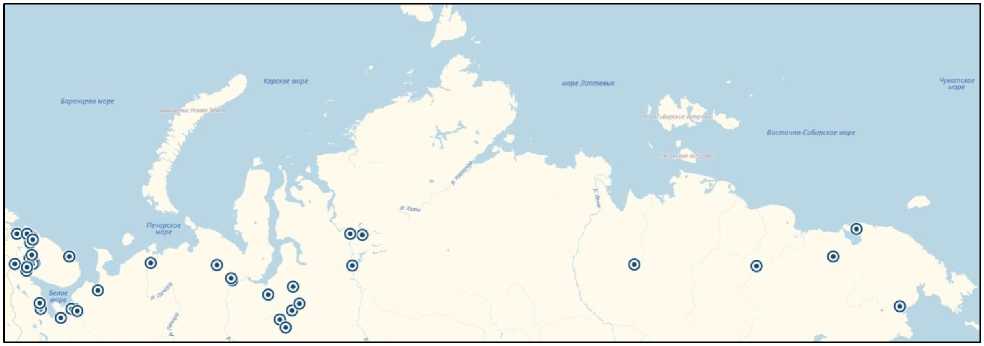

territories, economic specialization and administrative functions [10, Ethnonacionalniy, pp. 84–85, 130]. In total, AZRF has 41 settlements with the official status of the town. They are distributed over the territory of the Russian Arctic, of course, unevenly (Fig. 1): the highest concentration is in the Murmansk region.

Fig. 1. Distribution of towns on the territory of the Russian Arctic.

Various criteria can distinguish urban settlements in the Arctic zone. First, it could be done by population and agreed to the Code of Rules SP 42.13330.2011 “Urban planning. Planning and development of urban and rural settlements ”, in Russia there is a formal division of settlements into the largest (over 1 million people), large (from 250 thousand to 1 million people), large (from 100 to 250 thousand people), medium ( from 50 to 100 thousand people) and small (up to 50

thousand people)13. As it can be seen from table 3, there are no major towns on the territory of the Russian Arctic, which is related to the difficult climatic conditions for living, as well as problems of transport communication in the conditions of the Far North. Major towns are only Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Most towns are small. However, here it is necessary to make a reservation that the status of the city is sometimes very conditional since some urban-type settlements have long overtaken the “town” in terms of population. E.g., the population of the town of Nickel (Murmansk Oblast) is 11,437 people, and the town of Mezen (Arkhangelsk Oblast) is 3,267 people.

Table 3

Information about the types of towns in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation 14

|

Territory |

The largest |

Large |

Large |

Medium |

Small |

|

Murmansk Oblast |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

13 |

|

The Republic of Karelia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Arkhangelsk Oblast |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

|

Nenets Autonomous District |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

The Komi Republic |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

6 |

|

Krasnoyarsk Territory |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Chukotka Autonomous District |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

Total |

0 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

32 |

Towns of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation also differ based on their different purposes, which also determines the composition of the urban population. Allocate the reference city (Arkhangelsk and Murmansk), which are the bases for the development of the Arctic space, and because of the most numerous and multi-tasking. There are also cities that perform a variety of administrative, cultural, transport and other functions [12, Fauser V. V., Lytkina T. S., Fauser G. N., p. 43]. The legacy of the Soviet past is industrial (often mono-profile) towns and closed administrative-territorial formations. These types have experienced and are experiencing various effects of migration processes, incl. migration of representatives of other socio-cultural space. E.g., Arkhangelsk is now taking in the first-place intraregional migration, although for various reasons representatives of different regions of the country with their cultural peculiarities flocked here during the 20th century. And the towns of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous district continue to host the interregional migration flows: this is mainly a seasonal migration of workers, i.e., shift workers, but there is no return migration.

It is hardly possible to distinguish the towns of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation according to the ethnic-confessional criteria, since the absolute majority of the population is related to the Russian ethnic group, which traditionally tends to official Orthodoxy in its confessional preferences (the problems of determining the ethnic-confessional group are mentioned in the in- troduction of the article). In extreme cases, you can differentiate the town by the number of representatives of an ethnic group or denomination.

History also provides a basis for the typology of Arctic cities. Only a small part of them was founded by various colonizers (settlers, monks, Cossacks, and others) in ancient times (e.g., Arkhangelsk, Kem, Kandalaksha, Salekhard, Srednekolymsk and others). Some towns were founded in the late 19th — early 20th centuries, which was associated with the emergence of public interest in the development of extreme North and, accordingly, with organized migration to the newly created settlements (e.g., Murmansk, Polar, Anadyr, and others). More than half of the Arctic towns were created in Soviet times from scratch, often on the site of mining. Moreover, it is even worth dividing them into cities founded in the pre-war period, when prisoners (e.g., Vorkuta) were often involved in the construction of the point and worked in it, and towns founded in the postwar period, when the development of populated locations was subordinated to the enthusiasm of geologists (e.g., Novy Urengoy).

These historical and cultural features of creating a network of towns in the Arctic determine the degree of satisfaction of ethnic and religious needs in the urban environment. In the old towns (even if in pre-revolutionary time they were only small settlements) naturally prevailed Russian population. Even in Siberia and the Far East, towns only occasionally attracted representatives of small indigenous peoples, especially if they were nomadic. Because of this, it is natural that in confessional terms, in the old towns, the official rule prevailed. It was expressed in the presence of one or more churches, which, of course, were perceived as necessary in ethnic and confessional terms for a comfortable life in the city. In younger towns created before the revolution 1917, too, as a rule, managed to build a Church: e.g., in Aleksandrovsk (now Polyarny). But it is obvious that not all pre-revolutionary confessional structures were able to survive the years of the Soviet struggle against religion. At best, the buildings were converted to the needs of the national economy and Soviet power. There are rare examples of churches that have retained the opportunity to conduct worship.

Naturally, in such conditions, it was not possible to create confessional institutions and structures in young towns of the Soviet Arctic. But then there was no need for them. But a new era in 1990 caused a surge of interest in religion. It was due to the appeal to their roots (not only in Russian), and the search for ideological guidelines in a state of social anomie, and the desire to atone for the sins of the past, and, of course, with elementary fashion. In the end, in the old towns gradually begin the restoration of ruined churches marked the restitution of religious property preserved. Both in the old and the new cities, the construction of religious buildings is unfolding, while it is important to note that sometimes even more activity is shown by representatives of Islam and Protestant denominations rather than official Orthodoxy. As a rule, the creation of such objects of the urban environment is a response to the request of the population. But what we have now, looks quite chaotic.

As a rule, in small towns of the Arctic, there must be one or two Orthodox churches, and in most cases, there is a religious institution of one of the Protestant denominations. If the town belongs to the old settlements, there are cases when the Orthodox Church is an original prerevolutionary structure (or restored in the last 20-25 years in the same place). It means that it is in the heart of the city, accessible to the needs of the local population. At the founding of the settlement in Russia, whether in the 17th century or the 19th century, its center has always been considered one or another institution of public purpose, and, of course, the Church was the place of attraction of parishioners, it had to converge convenient ways. Therefore, in such towns and the Church is in a convenient location to meet the needs of religious citizens, which also makes the urban space comfortable. E.g., in Mezen (Arkhangelsk Oblast) the old Cathedral (though slowly rebuilt) is located on the main avenue of the town, which allows holding ceremonies with the participation of everyone.

In young town, churches were built and are being built in places available for construction. And if in the center of the free space, due to the solid construction of the Soviet time, no longer, the temple must be located on the outskirts. E.g., in Tarko-Sal (Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District), churches are located far from most residential buildings. There are, of course, exceptions. E.g., in Pevek (Chukotka Autonomous District), an abandoned building, a former residential building in the center of the town, was converted into a Church.

As for Protestant organizations, in a significant number of cases, they are registered in residential premises of apartment buildings. Registration in residential premises is also typical among Orthodox and Muslim organizations15. But they usually have their own separate, roomy buildings for comfortable participation in the divine services of citizens. The prayer rooms of the Protestant denomination of nations are in the same residential premises (sometimes in private houses). Of course, this is primarily due to the small size and fragmentation of the Protestant communities, as well as the lack of support from the municipalities (often Protestant denominations are perceived by the public alert16). At first, it is possible for believers to gather in the apartment of the presbyter conveniently. But when expanding the community, it is necessary to build its special facility. At the same time, there is also a place for it in the suburbs of the town (e.g., a Baptist church in Apatity, the Murmansk Oblast) or, at best, in a promising area for development (e.g., a Lutheran church in Kemi, the Republic of Karelia). Of course, there might be exceptions. E.g., in Kandalaksha (the Murmansk Oblast), the Evangelicals and Adventists are located much closer to the center of the town than the Orthodox church.

A special situation arises concerning representatives of other faiths. Catholics are registered as a community only in Arkhangelsk, Norilsk, and Murmansk, and there is only one church in the latter. Buddhists are only in Arkhangelsk and Severodvinsk, but they do not even have their temples there. Judaism is represented in the organizations of Murmansk, Norilsk, Severodvinsk, and Arkhangelsk, where its temple has recently appeared. Islam is developing more successfully in terms of creating its objects. Today, the mosques are in ten towns of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation, six of which belong to the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District. At first, this may be surprising, because the Nenets, the Selkups, and the Khanty are considered indigenous to this territory and they are not Muslims.

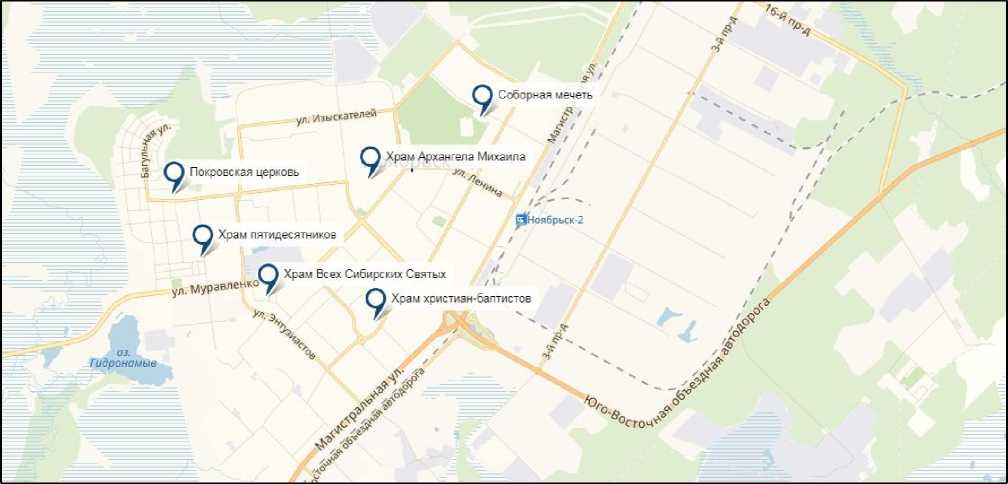

Also, the area has a harsh climate, and therefore it is not attractive for migration. But the determining factor for immigration in this area is, of course, the economic situation and mining industry. Today, among the population of the area: 5.6% — Tatars, 1.7% — Bashkirs, and 7% represent peoples of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Since the beginning of the 2000s, there was an increase in the number of the last 1.4 times. The share of Muslims in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District increased from 1.7% to 12% [10, Ethnonacionalniy, pp. 132, 228]. These people live in towns mostly. At the same time, we should not forget about the shift workers, who may also need spiritual practices in mosques. Since the towns of the area were mainly built in the Soviet era, when it was impossible to even think about creating religious buildings, mosques were built where conditions allowed, and therefore they are mostly located on the outskirts. The Noyabrsk (Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District) has both Orthodox churches, Protestant churches, and a mosque and they are relatively close. It seems to be the most successful variant of the placement of religious institutions (Fig 2).

Fig.2. Location of religious objects in Noyabrsk.

The capacity of the temples is different, but it is also important that the adjacent territory, as a rule, is enough for comfortable accommodation of believers during holidays and on the streets. This is a significant factor in the comfort of urban space.

Cases of reference towns in the Russian Arctic

It is important to consider the cases of the two reference cities of the AZRF: Arkhangelsk and Murmansk separately. In terms of population, both cities are large cities but differ in their origin.

Arkhangelsk is an old city, which began at the end of the 16th century. It was created near the religious buildings of the Archangel Michael Monastery. Later, when the monastery was moved to the outskirts, Orthodox religious buildings still defined the logic of the development of the city. Several central streets began at one or another of the temples (and had the appropriate names), so it is logical that the residents of these "neighborhoods" became parishioners of these temples. Since Arkhangelsk was created for the tasks of international trade, it is not surprising that in the17th-18th centuries, representatives of European nations began to settle here, incl. those that professed Catholicism and Protestantism. They had their church and church, which were for them a center for the preservation of national traditions. By the beginning of the 20th century, Jewish and Tatar communities also formed in Arkhangelsk, which had a synagogue and a mosque, respectively. Of course, they were no longer located on the main avenues (Embankment and Troitsky), but still not in the outskirts.

In Soviet times, much of the religious buildings were either destroyed (such as the Trinity Cathedral, the Assumption and the Annunciation churches, the Catholic church, etc.) or redeveloped for the needs of the Soviet authorities (e.g., the Holy Trinity Church). , church, mosque). In Soviet times, the cemetery Ilyinsky church, which for a long time was the cathedral church of the diocese, was practically not closed.

After the USSR, all the surviving buildings of religious purposes began to be gradually transferred to the jurisdiction of the respective denominations. The Orthodox church not only received back and restored part of its temples, but also launched the planned construction of churches in various districts of the city. Today, each district has its center of attraction for believers, but the capacity of these structures is not always satisfactory. Their location is also not still convenient; some citizens must get to their parishes on city buses. Placement of temples rarely allows worship in the street, including religious processions. The most convenient adjoining territory is the new Church of Alexander Nevsky, it will enable it to become a socially significant object, to hold events, including those not related to religious activities. Restored at the same place, the Assumption Church at the expense of the graceful exit to the river and the promenade attracts newlyweds. Ilyinsky temple is extremely inconvenient in many respects because it was initially a cemetery church. In exchange for it, for several years now, a large cathedral in the name of Archangel Michael is built in the very center of the city, where the traffic interchange is located. The temple is situated on a spacious area, which is supposed to be reconstructed, considering religious needs17.

Even though the state in Russia is officially equidistant from all denominations, it is logical that the Russian Orthodox Church received this territory for the construction of religious buildings. Orthodoxy is considered traditional for these places and therefore may well support the needs of a significant number of citizens.

Similarly, the local diocese is negotiating with the municipality about the prospects for the construction of new churches. So, e.g., the worship cross marked the place for the future construction of the temple on a small site in the very center of Arkhangelsk (not far from the mosque!). Mayor Godzish I.V. frankly declares that “it is necessary to reserve land plots for future temples and Sunday schools, in order not to encounter any further situation when this kind of object is essential for the population, and it has to be wedged into the existing building.”18 It is separately discussed that the territories around the temples will be landscaped, which is of no small importance in the implementation of the program “Formation of a comfortable urban environment.”

Other denominations are also gradually recovering their positions. At the beginning of 2018, a mosque was restored, which is the new historical conditions turned out to be in the geographic center of Arkhangelsk.19 Although this is the restoration of historical justice, it is necessary to recognize that the mosque is sandwiched between the houses. Its area and the surrounding area are minimal for the construction of festive worship services. The streets where the mosque is located are quite narrow, and there are no free spaces around. Given the migration flows from the Muslim areas (although not as significant as in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District), it must be assumed that the need for a mosque will increase. Consequently, now we need to think about building new Muslim objects in promising districts of the town (especially in those where Islamic peoples can concentrate).

Also, at the end of 2018, a synagogue was opened in Arkhangelsk20. It was not a restoration, but construction in a new place. Although geographically, the synagogue is in the center of the town, in a very inconvenient place, away from the road, near construction sites and technical areas. But the building itself is positioned not just like a synagogue; it has a multifunctional character: religious purpose, public space, a teaching audience, a cafe and so on. For a small Jewish population, this building is a place of preservation of national traditions.

Protestant denominations are also widely represented in Arkhangelsk, some of their prayer rooms are in apartments or private houses (e.g., the New Apostolic Church in the very center of the town, next to the mosque). These spaces are quite enough to accommodate a small number of believers of the corresponding Protestant denominations. Among others, Seventh-day Adventists, who acquired the territory in the most promising district of Arkhangelsk and built their brick building with an adjacent territory, stand out among others. Now, this is a very convenient place for parishioners, and the temple fits into the urban landscape.

As a result, it can be said that Arkhangelsk fully satisfies the diverse needs of citizens in the administration of worship. But the location of specific religious constructions is sometimes incon- venient. In the intensive development of the central districts, there is no room for the prospective creation of large ethnic-confessional objects. In marginal areas, especially promising for residential development, it is necessary to provide places for the possible construction of Orthodox churches, mosques and other religious institutions.

Ижма

^^ Церковь Ксении Петербурге к...

о. Повракульский

Талаги riOBf.

riOBf.

тьские остр

Храм Святителя Тихона Мартина Исповедн...

(^ Троицкая церковь ----

Мечеть :тппнская пепковь

ApxahSCD Собор Михаила Архангела

■рхачёво

Пуново

Волохница

Большая Корзиха

Новое Лущима

Храм Александра Невского

' (^ Храм взыскание погибших

Турдеевск гиевская церковь

Уемский'*

Fig. 3. Location of religious objects in Arkhangelsk.

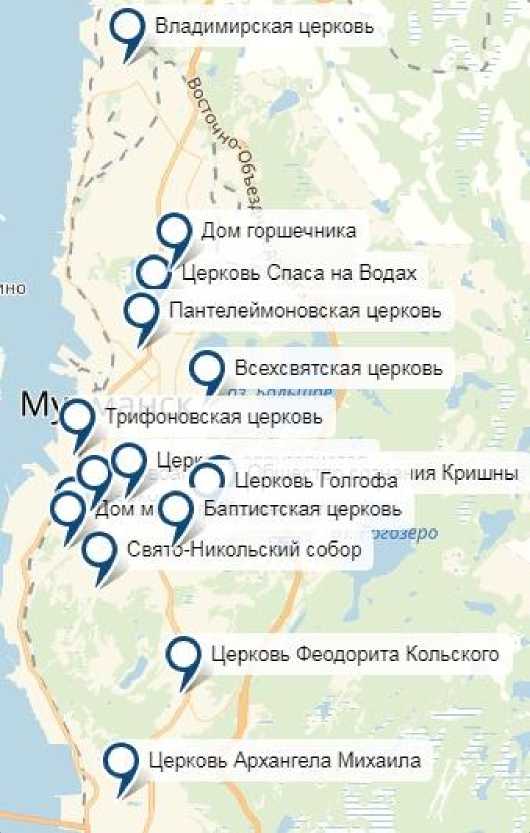

Murmansk is a relatively young town. It was founded last in the Russian Empire. And, as it was customary, the beginning of the town was the construction of an Orthodox church (Nicholas the Wonderworker church). But because of the revolution, this temple was never completed, its place is occupied by the Palace of Culture (very symbolic for the Soviet era). Subsequently, at the end of the Soviet era, the temple was still built, only in a completely different place: on the southern outskirts of the town. At the same time, the church of Trifon of Pechengsky was also built. The main construction was launched at the turn of the 20th-21st centuries. Particularly active in making decisions about the construction of various religious buildings was the year 200421.

Murmansk, like Arkhangelsk, has Orthodox churches in almost every district of the city. However, in the very center of the town (both geographically and publicly, politically and culturally), the Orthodox have only a chapel in the name of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker near the unfinished building site of the first church. It is not surprising: with the dense development in the Soviet period, each space of the city had a specific purpose. And now, although the green areas in the city center have been preserved. It does not mean that they are empty. It is impossible to fit even a small church there not only by technical standards but also by considerations of public resonance. The majestic Church of the Savior of the Hand-to-hand Image (Sea Temple) is located on the semi-periphery of the town. Space is quite convenient: apartment buildings are nearby, while the temple itself stands in open space. The construction of a new Spaso-Preobrazhensky maritime cathedral assembly is planned at this place22. Also, 13 churches have already been completed: three Orthodox churches have based on premises assigned for worship, and the other ten — for donations.

Catholics in Murmansk are since the beginning of the town, and they even received permission to build a church, which, however, did not take place because of the revolution.23 Local Catholics found their temples only in the modern era. The majestic catholic church of St. Michael, though located on the outskirts of the town, at the same time in a park area with wide spaces. The Catholic Church of Saint Helena is also far from traffic interchanges, but not far from it are the buildings of Murmansk State Technical University. The new building, the evangelists, the Baptists have their territory and from scratch built a large building. Their communities are mainly distributed along the outskirts of the city, which is quite logical and promising for the development of the town. Muslims of Murmansk also have their own multifunctional prayer house on the outskirts of the city24. Nearby in the two-story house is the Murmansk Branch of the Society for Krishna Consciousness.

Like Arkhangelsk, Murmansk is a city stretched along with the water space from north to south, which determines the inaccessibility of social and cultural facilities for all residents of the town. But the geographical landscape of Murmansk brings additional features. The location of objects is often inconvenient, which limits the satisfaction of ethnic and religious needs in an urban environment. At the same time, the city is relatively young and promising; therefore, it is already necessary to think that in the north, east and south of the town, it is worth planning the possible sites for the construction of these religious objects.

Fig. 4. Location of religious places in Murmansk.

Conclusion

Thus, it becomes evident that the formation of a comfortable urban environment is impossible without considering ethnic-confessional factors. The location and functional possibilities of ethnic-confessional institutions or objects are of great importance in the life of urban communities. An example of Russia's most significant metropolis in Moscow shows how to create a comfortable urban environment. This experience should be considered in the towns of the Russian Arctic, formed mainly in the Soviet time without attention to ethnic-confessional factors. Since the 1990s, religious and ethnonational structures and objects were chaotically created in these municipalities. As a result, the unsystematic nature of their placement is evident today. The current ethnic-confessional and migration situation in the Russian Arctic establishes the need to revise the attitude of the regions and municipalities to the idea of comfort in the urban environment. Although in the large, reference towns of the area — Arkhangelsk and Murmansk — a significant spectrum of ethnic-confessional groups is represented, not all of them are sufficiently satisfied with the location of their religious and ethnonational institutions. Large, medium and small towns of the Russian Arctic probably still must face ethnic-confessional factors of forming a comfortable urban environment.

Based on the previous, we would like to give a few recommendations to the municipal administrations. Since the construction of new cities in the Russian Arctic shortly is unlikely, these recommendations apply not only to the existing towns but also to urban-type settlements, which may soon officially acquire the status of towns. Sarvut T.O. notes that it is necessary not only to provide urban residents of the Arctic regions with a decent level of comfort but also to create socio-cultural objects. It should consider the historically established principles of organization of both the indigenous and permanent population [13, Sarvut T.O., pp. 170–171]. We believe this to be correct; however, since the state (represented by state and municipal authorities) in Russia is separated from ethnic and religious preferences, the administration cannot independently participate in the creation of such objects. The municipal authorities need to regularly monitor public opinion, as well as the ethnic-confessional composition of the urban population. Public hearings, often held formally, do not reveal the whole range of views and needs of the residents of the municipality. Based on the beliefs and interests of citizens, it is necessary to plan the renovation of the former town zones and prospective development. When designing new urban areas, it is essential to systematically allocate spaces for the creation of objects of ethnic or cultural purposes. It does not mean that the town administration will invest in construction. It would be better to bring to the public discussion of the creation of such sites. If the population needs to create an ethnic-confessional object, the city administration will have to agree on a plan for further actions with the leaders or organizations of the relevant ethnic group or denomination. The future facility should be integrated into the urban landscape and contribute to the formation of comfortable urban space.

Acknowledgments and funding

The article is a part of a study supported by a grant from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research — Project No. 18-411-290010 “Models of communicative management in the development of urban space (case of the Arkhangelsk Oblast)”.

Список литературы Ethnic and confessional factors of comfort of the urban space in the Russian Arctic

- Gol'c G.L. Gorod i ego kul'turno-urovnevye pokazateli v opredelenii i izmerenii urbanizacii [The city and its cultural and level indicators in defining and measuring urbanization]. Gorod kak soci-okul'turnoe javlenie istoricheskogo processa [The city as a socio-cultural phenomenon of the histori-cal process], Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1995, pp. 47–60. (In Russ.)

- Gorodkov A.V. Nekotorye kul'turologicheskie aspekty sohranenija istoricheskoj zastrojki goroda [Some cultural aspects of the preservation of the historical buildings of the city]. Regional'naja kul'tura: innovacionnye aspekty razvitija: materialy mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konfer-encii [Regional culture: innovative aspects of development]. Ed. by T.I. Rjabova. Brjansk, BGITA Publ., 2014, pp. 9–17. (In Russ.)

- Shepelev N.P., Shumilov M.S. Rekonstrukcija gorodskoj zastrojki [Reconstruction of city building]. Moscow, Vysshaja shkola Publ., 2000, 271 p. (In Russ.)

- Kataeva Ju.V. Asimmetrija interesov subjektov preobrazovanija gorodskoj sredy kak faktor ee nesbalansirovannogo razvitija [Asymmetry of interests of subjects of urban environment transfor-mation as a factor of its unbalanced development]. Perm University Herald. ECONOMY, 2013, no. 3 (18), pp. 129–137.

- Kopytova Ja.K. Gradostroitel'nye aspekty obespechenija migracionnyh processov [Town planning aspects of migration processes]. Ustojchivoe razvitie territorij: sbornik dokladov mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konferencii [Sustainable development of territories], Moscow, MISI–MGSU Publ., 2018, pp. 43–46. (In Russ.)

- Zaikov K.S., Kalinina M.R., Kondratov N.A. Tamitskii A.M. Innovation course of economic develop-ment in the Northern and Arctic territories in Russia and in the Nordic countries. Economic and So-cial Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2017, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 59–77. DOI 10.15838/esc/2017.3.51.3

- Zaikov K.S., Katorin I.V., Tamitskii A.M. Migration attitudes of the students enrolled in Arctic-focused higher education programs. Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast, 2018, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 230–247. DOI 10.15838/ esc.2018.3.57.15

- Zaikov K., Tamitskiy A., Zadorin M. Legal and political framework of the federal and regional legisla-tion on national ethnic policy in the Russian Arctic. The Polar Journal, 2017, no. 1 (7), pp. 125–142. DOI 10.1080/2154896X.2017.1327748

- Sokolova F.H. Jetnodemograficheskie processy v Rossijskoj Arktike [Ethno-demographic processes in the Russian Arctic]. Arctic and North, 2015, no. 21, pp. 151–164.

- Jetnonacional'nye processy v Arktike: tendencii, problemy i perspektivy: monografija [Ethnonational processes in the Arctic: trends, problems and prospects: a monograph]. I.F. Vereshhagin, K.S. Zaj-kov, A.M. Tamickij, T.I. Troshina, F.H. Sokolova, N.K. Harlamp'eva i dr.; / Ed by. N.K. Harlamp'eva. Arhangel'sk: NArFU Publ., 2017, 325 p. (In Russ.)

- Fauzer V.V., Lytkina T.S., Fauzer G.N. Rasselenie naselenija v rossijskoj Arktike: teorija i praktika [Settlement in the Russian Arctic: Theory and Practice]. Dinamika i inercionnost' vosproizvodstva naselenija i zameshhenija pokolenij v Rossii i SNG: VII Ural'skij demograficheskij forum s mezhdu-narodnym uchastiem: sbornik statej [Dynamics and inertia of reproduction of the population and replacement of generations in Russia and the CIS: VII Ural demographic forum with international participation]. Vol. 1: Sociologija i istorija vosproizvodstva naselenija Rossii. Ekaterinburg Publ., 2016, pp. 126–132.

- Fauzer V.V., Lytkina T.S., Fauzer G.N. Osobennosti rasselenija naselenija v Arkticheskoj zone Rossii [Features of population settlement in the Arctic zone of Russia]. Arctic: Ecology and Economy, 2016, no. 2 (22), pp. 40–50.

- Sarvut T.O. O principah formirovanija sredy obitanija v rossijskoj Arktike. Ustojchivoe razvitie terri-torij: sbornik dokladov mezhdunarodnoj nauchno-prakticheskoj konferencii [On the principles of habitat formation in the Russian Arctic. Sustainable development of territories]. Moscow, MISI–MGSU Publ., 2018, pp. 170–172.