Ethno-Cultural Space of the Russian North as the Basis for the Development of Recreational Nature Management and Tourism

Автор: Sevastyanov D.V., Grigoryev A.A., Podshuveyt O.V.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 60, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The purpose of the study is to draw attention to the issue of developing domestic tourism in the North-West region of the Russian Federation and preserving unique historical and cultural heritage sites in the Russian North. Generalization of global experience shows that recreational nature management, domestic tourism, and international Arctic cruise tourism in the northern countries are currently becoming increasingly widespread and can have a significant economic impact. As a result of the field historical and geographical studies conducted by the authors on the territory of the North-Western Federal District of the Russian Federation and analysis of literature and exhibitions of cultural heritage sites presented in regional Arctic museums, the rich historical and cultural tourism potential of the region has been revealed. Special attention is paid to the reconstruction of routes along ancient waterways. These routes contain the most valuable natural and cultural heritage sites that are of interest to tourism and require protection and promotion. The possibilities of using the exhibits of local history museums in the Arctic region for the preservation of heritage sites and the development of local history, recreation, and tourism are considered. It is shown that the modern development of tourism and recreational nature management should contribute to the sustainable development of the northern regions of the country.

North-Western Federal District, recreational nature management, tourism, ethno-cultural space, heritage sites

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148331898

IDR: 148331898 | УДК: [338.48:39](470.1)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2025.60.222

Текст научной статьи Ethno-Cultural Space of the Russian North as the Basis for the Development of Recreational Nature Management and Tourism

DOI:

The development of rational nature management and the promotion of the protection of natural, historical and cultural resources are key areas of research in modern recreational geography. They are particularly relevant at present in the context of the intensification of domestic tourism in the Russian Federation. In this regard, the geographical location and border proximity to some European countries, the natural conditions of the North-Western Federal District of the Russian Federation (NWFD), and the presence of a number of unique natural and cultural heritage sites in the region determine the significant cognitive potential for participants in both domestic

-

∗ © Sevastyanov D.V., Grigoryev A.A., Podshuveyt O.V., 2025

This work is licensed under a CC BY-SA License and inbound tourism. There are many sites of historical interest to tourists, ranging from the Paleolithic to the Middle Ages and modern times. The presence of some ancient megalithic monuments in this territory, taking into account their location in the relief, orientation to the cardinal points and the identification of their connection with existing toponyms, show traces of early (possibly pre-glacial) human development of this region. There are ancient traces of active use of waterways in the dense network of lakes and rivers in the taiga landscapes, and the location of ancient settlements of representatives of different ethnic groups on the watersheds. In this region, there are numerous small and large settlements, preserved medieval wooden and stone residential and temple buildings, monastery architectural complexes, historical cities. All of this represents ancient centers of settlement and forms the basis of the high tourist attractiveness of the North-West region of the Russian Federation. Favorable factors for the development of tourism in this region are proximity to the center of the Russian Federation, a relatively developed transport network, the presence of natural and cultural heritage sites, museums, national parks, hotels, tourist centers and other tourist accommodation facilities.

The cultural and natural heritage of the Arctic forms the basis for the territorial-spatial development of the geopolitical and geostrategic framework of Russia as a state with a centuries-old history and culture of world significance.

Ethno-cultural features of the North-West region of the Russian Federation

The North-Western Federal District of the Russian Federation has become an increasingly popular tourist region over the past ten years. Each of the administrative entities of this federal district has attractive tourist sites and holds events to advertise and promote new locally created tourism products (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Administrative structure of the North-Western Federal District of the Russian Federation (NWFD RF) 1.

This federal district occupies about 10% of the total territory of the Russian Federation.

Within this region, an ethno-cultural space was historically formed, generalized by the concept of

-

1 Official website of the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in the NorthWestern Federal District. URL: http://szfo.gov.ru (accessed 14 June 2024).

the “Russian North”. This space includes, in whole or in part, the territories of modern Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Murmansk and Leningrad Oblasts, the Republics of Karelia and Komi, and the Nenets Autonomous Okrug. In recent years, an interregional tourism project launched in 2012 has been implemented in this territory — “Silver Ring of Russia”, but later a new tourism project was introduced — “Silver Necklace of Russia”, which unites tourism clusters formed in the North-West region and should contribute to the popularization of tourism in the Russian North. This brand now exists alongside the earlier one and continues to be enriched with new tourist attractions [1, Chistyakova T.N.].

It should be noted that a significant part of the sites of the “Silver Necklace of Russia” are located in the European part of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation. Undoubtedly, this part of the NWFD RF, which has a competitive advantage in tourism, can and should serve as a driver for the development of tourism infrastructure and the organization of tourism in all other northern territories of the Russian Federation and in the Arctic. The port of Murmansk and the ice-free Barents Sea are the outposts of the developing Russian Arctic cruise tourism, using the unique capabilities of nuclear icebreakers for travel to the North Pole and the islands of the Arctic Ocean. Cruise voyages on the icebreakers 50 Let Pobedy and Yamal start from here every year and are gaining increasing international popularity [2, Gadzhieva et al., pp. 66-67; 3, Fomin A.A., p. 327].

The popularity of tourism in the Arctic and northern regions of the Russian Federation is facilitated by the presence of the northernmost National Park in Russia — “Russian Arctic”, created in 2009 on the northern island of Novaya Zemlya and the Franz Josef Land archipelago. At the same time, for the first time in the world, special standards for Arctic tourism have been developed in accordance with the “Strategy for Developing the Russian Arctic Zone and Ensuring National Security until 2035” adopted by the Government of the Russian Federation. It provides not only for the improvement of the extractive industries of the country’s economy, but also for the development of tourism infrastructure, protection of the Arctic nature and other measures to popularize and increase tourist visits to the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation 2.

A distinctive feature of the North-West region of the Russian Federation is its partial territorial location in the Arctic zone, stretching along the shores of the Barents and White Seas, and the localization of a special ethno-cultural space here.

This area is characterized by a relatively high concentration of cultural heritage sites from different eras — sacred pagan temples and groves, traces of ancient medieval Slavic settlements founded by pioneers on the waterways along which the northern taiga was explored.

Here, in the Russian North, there is an abundance of ancient Christian shrines of various forms — ancient worship crosses, wooden chapels and tent-shaped temples, stone monastery complexes, etc. Therefore, the Russian North is a special region of Russian cultural heritage, which, in terms of its significance, can be compared to unique phenomena of world culture. In particular, this territory contains monuments that represent Russia on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

In the era of comprehensive globalization and unification, national and cultural ethnic identity is becoming increasingly valuable. Among the regions of the country, the Russian North has largely preserved the uniqueness of the culture and traditions of the Russian people. The cultural landscape of the Russian North is acquiring outstanding significance these days because it is a region of living traditional culture, a territory that preserves the cultural and natural heritage of the Russian North: the foundations of the ancient northern Russian Orthodox life, which make up the unique ethno-cultural landscape of the Russian North, carefully preserved in museum exhibitions and studied by many researchers [4, Permilovskaya A.B. et al.; 5, Semushin D.; 6, Grigoryev A.A. et al.].

Currently, the Russian North is a historical region of Russia that is gaining popularity in the Russian tourism industry as a promising destination for nature-oriented travel, historical, cultural, and religious tourism. Here, in the north of the East European Plain, in the land of taiga lakes and “white nights”, pre-Christian megalithic complexes are most widely represented, as well as other material and spiritual historical and cultural objects of both the Finno-Ugric and Slavic ethnic groups.

In addition, this region, especially the Barents region, can be considered a “refugium” of examples of ancient Russian wooden Christian temple architecture, relatively well preserved here since the 16th–18th centuries [7, Terebikhin N.M.; 8, Opolovnikov A.V.].

Historical materials and museum exhibits from the Arkhangelsk and Vologda Oblasts show that during the period of Slavic expansion into the European North, the territory from the Kola Peninsula and Lake Onega to the Pechora River and the Ural Mountains (Kamen) was inhabited by separate Finno-Ugric tribes: Lapps, Karelians and Vepsians, Chud, Nenets-Samoyeds, Permyaks, Komi-Zyryans and other small ethnic groups [5, Semushin D.L.].

Starting in the early Middle Ages, representatives of the Norman (mainly in Murmansk) and Slavic ethnic groups began to increasingly penetrate these sparsely populated areas, which were rich in forests, river pearls, fish, fur animals, and sea animals. From the relatively warm climate of the middle forest-steppe zone, the Slavs spread to the harsh north and north-east, to the Cold (White and Barents) Sea, along the banks of northern rivers and lakes, and then further to Yugra to Kamen (Ural), seeking to develop the natural resources of the northern outskirts of ancient Rus. It was only possible to travel across this taiga space by rivers and portages across watersheds. Thus, a “great water-portage route” emerged — from Onega to Yugra and further beyond the Urals, which is marked by traces of human activity: pagan megaliths and labyrinths, separate groves sacred to the aborigines, ancient camps and settlements of pioneers. The settlement of the Kola Peninsula and the colonization of Murman (Zemlya Tre) were carried out jointly by the Normans from Scandinavia and partly by the Slavs. The coast of the Studenoe Sea and the basins of the riv- ers flowing into it were populated mainly by people from the Novgorod, Pskov, Rostov and Suzdal lands. The settlers who inhabited the shores of the Studenoe Sea were called “Pomors”, and those who lived along the banks of rivers and lakes — “Porechens”. Important historical sites created by the “Pomors” and “Porechens” that are of interest to local historians and tourists include Christian chapels, churches, cemeteries and other monuments of historical and cultural heritage that have been preserved in the villages of the Arkhangelsk and Vologda Oblasts [8, Opolovnikov A.V.; 9, Grigoryev A.A. et al.; 10, Korostelev E.M. et al.].

The Slavs advanced northeastward along rivers and lakes, using the only possible waterportage routes in the taiga zone to reach the sea coast. The settlement was accompanied by the conversion of the local population to Christianity and the formation of a special Pomor sub-ethnic group, who settled on the coasts and islands of the Studenoe Sea and along the picturesque banks of the rivers and lakes of the northern region. It was the Pomors who began to introduce agriculture and the Christian faith in this region. Large rich villages and settlements arose on the watersheds through which portages were carried out, chapels and churchyards were built, Orthodox churches were constructed. Unfortunately, most of the ancient wooden church architecture has been lost to this day. This is especially true for the ancient portages across river rapids and interriver watersheds, as well as the settlements associated with them, which have been forgotten. However, these historical sites remain in the sphere of interests of local historians and tourists, as they are very attractive and can be the basis for organizing active water tours. Therefore, as the historian, professor Yu.A. Vedenin rightly states, “ancient portages, as unique monuments of the development of the North of Eurasia, need in-depth study, protection and popularization” [11, p. 16; 12, Sevastyanov D.V.].

It should be noted that in the Arkhangelsk Oblast, in addition to the UNESCO site that has existed since 1992 — “Historical and Cultural Complex of Monuments of the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea”, a second site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2024 — “Unique Cultural Landscape “Zapovednoye Kenozero””. It is part of the Kenozersky National Park, within which the once famous “Kenskiy Volok” is located. Ancient villages and cemeteries, old wooden churches and chapels, traditional northern landscapes have been preserved here. For its contributions to the preservation of natural and cultural heritage and the popularization of the history of the Russian North, the Kenozersky National Park was awarded the State Prize of the Russian Federation in 2022.

Some valuable materials on the history of the settlement of this northern region from the Middle Ages to the present day are available in the local history museums of Kargopol, Arkhangelsk and Vologda, which have rich collections of exhibits related to the development of the regions of the Russian North and the Arctic. The experience of the museums of the Arkhangelsk Oblast in preserving and promoting the cultural heritage of the Russian North and the Arctic is the object of cultural studies research. An important example of preserving the cultural heritage in the Russian North is the Museum of Wooden Architecture “Malye Korely” located near Arkhangelsk, founded in 1964. The open-air museum has many wooden buildings representing the traditional wooden architecture of different regions of the Arkhangelsk Oblast: “Kargopolsko-Onezhskiy”, “Dvinskoy”, “Mezenskiy” and “Pinezhskiy” — from small storage warehouses on stilts to windmills and bathhouses, peasant houses and tall wooden Christian cathedrals. The oldest of them date back to the 16th century.

Thus, the very existence of these museums and the presence of unique exhibits related to the development of the northern territories of Russia are of interest to researchers of the development of the northern regions and serve the cause of further development of tourism in this northern region [13, Andreeva T.A. et al.].

As historians note, the active expansion of the Slavs from the forest-steppe zone to the northeast, into the taiga and tundra landscapes, and the colonization of free territories began in ancient Rus in the 10th–12th centuries. One flow of settlers went from Novgorod and Staraya Ladoga on the Volkhov River to Zavolochye (beyond the portages), to the shores of the Studenoe Sea and further along the rivers through the watersheds to the east into the Pechora River basin to the Ural Stone. The second flow went from Rostov and Suzdal to Vologda and Beloe Lake, and along the Sukhona River to the Northern Dvina and to the Studenoe Sea. Thus, on the territory of the Russian North, the “Great Water-Portage Route” was formed along rivers and lakes through portages to Yugra and further — beyond the Ural Stone and into Western Siberia [5, Semushin D.L.; 9, Grigoryev A.A., et al.].

It should be noted that the expansion of the Slavs to the north was accompanied by the displacement and replacement of local pagan shrines with Christian ones. Aboriginal tribes were introduced to new Slavic cults, Orthodox religious rites, traditions and concepts. The Christianization of the local peoples of the north was a long historical process. Researchers note that in the process of introducing Christianity to the Russian North, there was a “new illumination” of former pagan shrines. Symbols of the new Orthodox faith were often located in their place (or nearby) — worship crosses, chapels, churches and temples were built. Based on his research, ethnographer, professor N.M. Terebikhin revealed a clear tendency to “replace” pagan, “unclean”, cult territories and objects with Christian ones. At the same time, the sacredness of such places acquired another — “positive” — meaning in the perception of the majority of the Slavic population migrating to the north [7, pp. 47, 116].

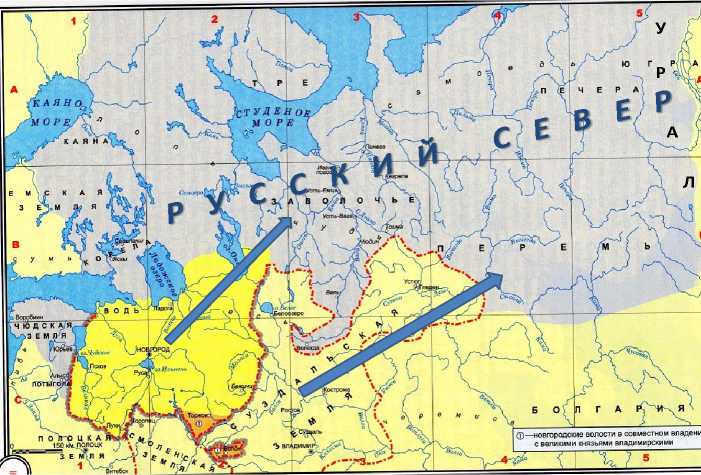

The main directions of the Slavs’ advance into Zavolochye (to the Russian North) are shown on the map (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The routes of the Slavs’ expansion into the territory of Zavolochye 3.

The symbols of replacement of some sacred objects by others include, for example, the first Christian chapel (White Skete), built on the site of a pagan temple dedicated to the god Veles, on one of the islands of the Valaam archipelago (see Fig. 8) and the modern Christian chapel standing on the pagan Kon-Kamen on Konevets Island in Lake Ladoga (published in [15, Grigoryev Al.A.]).

Stone monuments in the geo-cultural landscape of the Russian North

A distinctive feature of the landscapes of the Russian North is the widespread presence of ancient stone monuments, represented by individual megaliths (large boulders and rocks standing out in terms of their shape), petroglyphs (rock carvings) and stone labyrinths. Megaliths, represented mainly by menhirs and seitas, as well as individual large stone boulders of unusual shapes, are widespread in the Russian North. Their origin is of great interest to researchers, local historians and tourists. A menhir is usually a vertically standing megalith made of roughly processed stone or a stone block, whose height significantly exceeds its width or diameter. A seita is a large boulder lying on several smaller stones or located in an unstable position. Such stone monuments, often with zoomorphic features, are found on the islands and shores of the White Sea, in Karelia and on the Kola Peninsula. Seitas and menhirs can also be seen on the Karelian Isthmus, for example, in the Monrepos Park. They are widely represented in Karelia and the Murmansk Oblast, on the banks of Lake Seydozero and the Ponoy River, on Mount Seydapakh and Mount Vottovara. It is assumed that all these special objects were revered by ancient inhabitants — the predecessors of the modern peoples of the Russian North. They designate sacred places of local peoples, ancient objects of worship, which still have “exceptional significance and enduring value” [15, Grigoryev Al.A., p. 139].

-

3 Source: [5] with additions by the authors.

In most cases, researchers recognize menhirs as man-made. Local residents treat seitas as sacred objects. They can be considered iconic elements of the geo-cultural landscape. They are studied from the perspectives of geomorphology and cultural geography.

However, the anthropogenic origin of such megalithic objects as seitas is often questioned and causes heated debates among geologists, archaeologists and paleogeographers [16, Mar-sadolov L.S. at al.].

Petroglyphs (rock carvings, mainly zoomorphic images) are quite common in the Russian North. The sizes of petroglyphs vary from a few centimeters to 3-4 m. The largest concentrations of petroglyphs are found on rocky shores and islands in three locations: on the coast of the White Sea in the lower reaches of the Vyg River and on Kanozero (over 3,400), on the Kola Peninsula on the Umba River (over 1,500), on the eastern coast of Lake Onega (over 1,200). According to archaeologists, petroglyphs on the White Sea and Lake Onega were created 5–6 thousand years ago, and on Kanozero — 4-6 thousand years ago (Fig. 3).

At all the indicated locations, rock carvings depict animals and sea creatures, as well as silhouettes of people, sometimes on skis or in boats, hunting and fishing. The petroglyphs predominantly depict living creatures inhabiting the surrounding forests, lakes and the sea. For example, the petroglyphs on the Vyg River depict a particularly large number of deer and elk, as well as (to a lesser extent) predators such as foxes and bears. Among the aquatic images on the petroglyphs of the North, there are beluga whales, otters, beavers and catfish. There are many birds among the petroglyphs of all three locations, especially swans. It is likely that the main migration route of migratory birds has passed through these places since ancient times.

It should be noted that among the diversity of the Onega petroglyphs, the images of the Sun and the Moon are noteworthy; among the White Sea rock carvings, images of a spiral (a sign of the cycle of life), similar to the Egyptian ankh sign (a symbol of life, eternity), and a snake (a symbol of the cyclical nature of time) stand out. The location of all three clusters of petroglyphs clearly shows that they are associated with their proximity to water bodies (the sea and lakes), which is associated with the peculiarities of life and getting food of ancient people. According to archaeologists, clusters of petroglyphs in certain areas were presumably intended for ritual actions in these places, which were considered sacred [16, Marsadolov L.S. at al.; 17, Paranina A.N., Paranin R.V., p. 208].

Fig. 3. On the left, there is a rock carving of aborigines (the carved figures are outlined with chalk). Coastal cliffs in the Vyg River bed. Republic of Karelia (photo by A.A. Grigoryev). On the right, there is a megalith — a stone sculpture called “akka” (stone woman) — an obvious ancient landmark on Mount Kivakka in the Paanajärvi National Park (photo by V.V. Gorbatovskiy).

At the same time, independent geographical studies of the White Sea and, to some extent, Onega petroglyphs, carried out by A.N. Paranina, showed that some of them are associated with specific cracks in the rock, conveniently chosen for their orientation to the cardinal points, significant for determining time, often on the same line with the sunrise or sunset on the days of the equinoxes. Orientation in time and space was probably important for the life of the aborigines, and this is why places associated with this activity became sacred. Currently, petroglyphs are very expressive elements of the northern ethno-cultural space, attracting tourists [14, Terebikhin N.M.; 17, Paranina A.N., Paranin R.V.].

Stone labyrinths are one of the remarkable ancient monuments of the Russian North. They are mysterious oval or round formations made of stones, with a diameter from several to 25 m, usually in the form of one or two spirals. The Pomors called them “Babylons”. In their center, there was always either a menhir (a vertically standing stone) or a pile of stones. Labyrinths are found all over the planet, but in Europe they are localized mainly in its northern part (there are about 500 of them). In the Russian North, there are about 50 labyrinths. They are distributed unevenly, but always near water bodies, mainly on islands, for example, in the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, on the islands and coast of the White Sea and on the Kola Peninsula. Archaeologists have suggested several versions of the purpose of these objects: the labyrinths represent burial structures; they are models of fish traps; finally, they are formations intended for ritual ceremonies related to hunting and fishing. In addition, they were considered sacred and ritual objects associated with the movement of celestial bodies and the Sun across the sky. Besides, northern labyrinths could be used as sacred objects and for ritual — magical — purposes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Study of the Labyrinth on Bolshoy Zayatskiy Island of the Solovetsky Archipelago in the White Sea (photo by A.A. Grigoryev).

However, only the geographical approach made it possible to prove, using natural measurements on significant days of the Solstice, that the labyrinths are man-made structures oriented towards the Sun. They were probably built to determine the time of day during the polar day, when the Sun does not set below the horizon. At the same time, the labyrinths could perform some calendar functions [17].

We have verified in practice that the shadow of the sun, for example, from a pole standing in the middle of the labyrinth (similar to a gnomon), will move in a circle, showing the time of day during the “polar day”. Consequently, the primary purpose, useful for the life of the northern peoples, could be the most significant determination of the time of day in summer with the help of a “sundial”, while the form of the labyrinths (“Babylons”) was probably intended for ritual magical actions.

Thus, the noted features of stone monuments show the important role of the Sun in the mentality of the ancient inhabitants of the European North, who knew how to use its position to measure time, without which human life would be difficult.

It should be noted that the greatest example of artistic carpentry is rightfully considered to be the wooden Church of the Transfiguration of the Lord, preserved on Kizhi Island in Lake Onega, topped with 22 domes and an abundance of barrels. According to legend, it was cut down with an axe and assembled without nails in 1714 on the site of a burnt-down church. The entire Kizhi Po-gost ensemble is represented by two wooden churches — the Transfiguration of the Lord and the Protection of the Blessed Virgin — and is complemented by a tent-roofed bell tower with 12 bells (Fig. 5).

The national parks — Paanajärvi and Vodlozerskiy in Karelia, Kenozersky in the Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russkiy Sever in the Vologda Oblast, Yugyd-Va in the Komi Republic and other protected areas that have sections of these ancient waterways on their territories or near them can use them to organize active tourist routes, to develop local history, educational tours and popularize historical and geographical knowledge [18, Zelyutkina L.O., Korostelev E.M., Sevastyanov D.V.].

Fig. 5. The Kizhi Pogost ensemble on Kizhi Island in Lake Onega 4.

The unique ensemble of the Kizhi Pogost and its dominant feature, the Transfiguration Cathedral, were restored and put into operation in 2021 as a museum and functioning church with a magnificent iconostasis. This unique site is rightfully recognized as a masterpiece of wooden architecture and is included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

However, some of the most ancient typical wooden old Russian tent-type churches preserved in the Russian North include the Nikolskaya Church, built in 1618 and located in the village of Purnema in the Arkhangelsk Oblast, on the Onega Peninsula of the White Sea (requires restoration), as well as the similar Ascension Church (1651) in the village of Piyala on the Onega River, which restorers have already returned to its original appearance in recent years (Fig. 6). In addition, there is the ancient wooden Annunciation Church (1719) in the village of Pustynka, the Transfiguration Church (1780) in the village of Turchasovo, and a number of other preserved and requiring protection various unique objects of wooden church architecture, located in villages on the banks of the Onega, Northern Dvina, Sukhona, Vychegda and Pechora rivers, which decorate the modern northern landscape.

-

4 The iconostasis has returned to the Transfiguration Church on Kizhi Island. URL: http://rk.karelia.ru/social/culture/v- preobrazhenskuyu-tserkov-na-ostrove-kizhi-vernulsya-ikonostas/ (accessed 14 June 2024).

Fig. 6. Ancient wooden church buildings on the waterways of the Russian North (on the left — Nikolskaya tent-roofed church in the village of Purnema (1618), on the right — Ascension Church in the village of Piyala (1651) 5.

National parks as natural and ethno-cultural reserves

A unique ethno-cultural museum with a collection of Old Russian wooden architecture objects of the Kargopol region in the Arkhangelsk Oblast was formed on the territory of the Ke-nozersky National Park, which was organized in 1991. The vast territory of the National Park, adjacent to Kenozero and Lekshmozero, is located on the watershed between the Varangian (Baltic) and Studenoe (White) seas, through which the famous Kenskiy portage passed. In this special sacred space of Kenozeria, in the villages of the National Park, one can find ancient log huts, two-storey wooden houses and barns of the 17th–19th centuries. More than 70 unique wooden monuments have been restored and preserved here: chapels, churches, graveyards built in the 17th-19th centuries, ancient residential huts, barns and mills, more than 30 worship and votive crosses, 49 sacred groves, 52 archaeological monuments. All this constitutes an invaluable ethnographic wealth. An amazing water mill has been restored and is in operation in the National Park, and wooden churchyards have been restored — Pochozerskiy in the village of Filippovskaya and Porzhenskiy near the Maselga moraine ridge, which is a remarkable narrow watershed between the basins of the White and Baltic Seas [8, Grigoryev A.A. et al.; 14, Terebikhin N.M.].

The Vodlozerskiy National Park, one of the largest in Europe, located next to the Ke-nozersky National Park on the border of the Arkhangelsk Oblast and the Republic of Karelia, is of no less historical and cultural interest. The main waterway of this park is the rapids of the Ileksa River, flowing from the Vetreny Belt ridge and flowing into the large Lake Vodlozero, from which the Vodla River flows, connecting it with Lake Onega. In ancient times, a waterway was used to

-

5 Source: URL: http://temples.ru (accessed 14 June 2024). Photo by V. Shilov (left) and D.V. Sevastyanov (right).

travel up the Vodla River from Lake Onega to Lake Vodlozero and further along the Ileksa River, through the Vetreny Belt ridge to the Studenoe Sea and the Solovetsky Islands. According to historians and local experts, in the Middle Ages, the Ileksa River was used for active trade relations between the inhabitants of Vodlozero and the Pomors of the Studenoe More, they descended into Lake Onega along the Vama and Vodla rivers flowing out of Vodlozero, or communicated with the inhabitants of Kenozeria through the Kenskiy portage. Historical sources claim that on one of the many islands of Vodlozero, on the site of an ancient pagan sanctuaries, a Christian monastery was founded in the 13th–14th centuries, and later the Ilyinskiy churchyard was organized, decorated with a majestic wooden church of Elijah the Prophet (Fig. 7). The first information about this churchyard appears in 1563 in the “Cadastre Book of the Obonezhskaya Pyatina” by the Moscow scribe Andrey Likhachev; in official documents, the “Vodlozerskiy churchyard beyond Onega” is mentioned [6, Terebihin N.M.; 18, Zelyutkina L.O., Korostelev E.M., Sevastyanov D.V.].

Currently, one of the islands of Vodlozero is home to a restored monument of wooden architecture — “Ilyinskiy Pogost” (Fig. 7, left), in which an active Orthodox monastery is located. Every year in August, on the Orthodox holiday of Ilyin’s Day, pilgrims and believers from neighboring villages, as well as numerous tourists, come to the island.

Fig. 7. Ilyinskiy Pogost on the island in Vodlozero in Karelia. (left); Kirillo-Belozerskiy Monastery on the shore of Lake Siverskoe in the Vologda Oblast (right) 6.

Stone monastery architecture in the Russian North became a complement, continuation and development of the wooden architecture widespread in this region. Stone churches and monastery complexes in the Russian North began to be built later than wooden ones, at the turn of the 15th–16th centuries, as fortified outposts on the borders of the Muscovite state. They are well preserved on the Solovetsky Islands, and on Kiy Island in the White Sea, on the shores and islands of Lakes Onega, Ladoga, Kozhozero, Vodlozero, Kenozero and Lekshmozero, Bely, Kubenskoe, Lach and others. This was associated with the strengthening of Orthodoxy and the centralization of the Muscovite state starting from the end of the 15th century. Currently, stone monastery complexes and churchyards located on the shores of lakes in the Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Novgorod and Pskov

-

6 Source: URL: https://dzen.ru/list/travel/izvestnye-severnye-monastyri (accessed 14 June 2024).

Oblasts, as well as in Karelia, are valuable objects of cultural heritage of Russia and attract numerous domestic and foreign pilgrims and tourists.

In the 16th-18th centuries, monasteries became fortresses and strongholds for Orthodoxy in the border regions of the country and in the Russian North. Most often, monasteries were built in picturesque locations on islands, in bends or at the confluence of rivers, often in places of former pagan sanctuaries, transforming them into Christian shrines. Such examples include the Kon-evetskiy Monastery on an island in Lake Ladoga and the Valaam Monastery with the majestic Transfiguration Cathedral, located on the largest island in Lake Ladoga (Fig. 8). The Valaam Monastery has been mentioned in chronicles since 1407. However, historians date the beginning of monastery construction to the 11th–12th centuries. It is known that the first skete (Bely) on one of the islands of the Valaam archipelago was founded in the Middle Ages, in the 10th–11th centuries, on the site of a pagan temple consecrated by Christians in honor of the God Veles (Volos) [15, Grigoryev A.A.].

Fig. 8. The Transfiguration Cathedral of the Valaam Monastery. The ancient Bely Skete is visible in the distance 7.

The Vologda Oblast is widely known as an area of ancient monastery development in the Russian North. More than 70 historical, architectural and engineering monuments are registered here, including masterpieces of ancient stone temple architecture, classified as protected sites of World and Federal significance. These include the monastery complexes of Ferapontov (UNESCO site), Kirillo-Belozerskiy, Goritskiy, Nilo-Sorskaya Pustyn, Ilyinskiy Cathedral at Tsypina Mountain, etc. Christian Orthodox shrines are carefully preserved on the territory of the National Park Russ-kiy Sever and annually attract thousands of pilgrims, domestic and foreign tourists. The Vologda land and the Beloe Lake area were mainly settled by people from Rostov Velikiy and Suzdal starting in the 13th century, but this happened in the conditions of severe rivalry with Velikiy Novgorod [5, p. 48].

-

7 Official website of the Valaam Monastery. URL: http://valaam.ru (accessed 14 June 2024).

The water-portage route from the Suzdal lands to the Kubenskoe and Beloe lakes, to the Sukhona River and further to the Northern Dvina passed through the watershed of the Volga and Northern Dvina basins, through the Slovenskiy and Krasny portages. Archaeological excavations show that the route across this watershed has been known since Neolithic times. The north-east was reached by boats along the Sheksna and Slavyanka rivers to Lake Nikolskoe, then by land to the Prozorovitsa River, then across Lake Kubenskoe and down the Sukhona River to the Northern Dvina and out to the Studenoe Sea. The first mention of the Slovenskiy portage is found in the Spiritual Charter of Dmitriy Donskoy and dates back to 1389. Monastic centers arose along this route on the Sukhona River — Vologda, Totma and Velikiy Ustyug with numerous majestic Orthodox churches [6, Grigoryev et al.; 18, Zelyutkina L.O., Korostelev E.M., Sevastyanov D.V.].

Conclusion

Concluding our historical and geographical overview, it should be noted that the northern territories of Russia, and especially the Russian North, are becoming an increasingly popular tourist destination. The tourism sector is beginning to play an increasingly important role in the socioeconomic development of the northern territories. Over the centuries, a unique ethno-cultural space has been formed in the European part of the Russian Federation, rich in sacred sites and ancient legends, monuments of history and culture of federal and world heritage. Currently, the North-West region of the Russian Federation is characterized by active socio-economic development and offers new directions of Arctic cruise tourism on nuclear icebreakers from Murmansk to the North Pole and to the islands of the Arctic Ocean, opportunities to visit National Parks, which differ in natural conditions and historical and cultural features. Tourists can get acquainted with ancient wooden and stone temple architecture, experience the peculiarities of everyday life in the Pomor Russian hinterland, visit various museums, and see the embodiment of fairy-tale elements, for example, the “residence of Father Frost” in Velikiy Ustyug.

Taking into account the accumulated experience in organizing both international tourism for groups from the DPRK and the PRC and in domestic tourism, it can be confidently stated that the cultural, historical and natural heritage of the Russian North is a relevant object of research with subsequent practical implementation of new tourist routes. It should be emphasized that the development of the northern regions of the Russian Federation in the 21st century should be guided not only by the economic benefits of industrial companies extracting minerals. Undoubtedly, the cultural and natural heritage of the Russian North forms the basis for the territorial-spatial development of the geopolitical and geostrategic framework of Russia as a state with a centuries-old history and culture of world significance. Particular attention should be paid to the diversity of formats of tourist activities from school educational and student scientific research to individual cognitive tourism. An urgent task of our time is to improve the transport and hotel infrastructure of the region in line with modern trends and plans for the socio-economic development of the northern regions of the Russian Federation, which place particular emphasis on tourism in the Arc- tic and northern regions of the country. At the same time, the structure of recreational nature management in the Russian North requires state support for the development of local history and tourism with the participation of schoolchildren and students, as well as assistance in expanding museum exhibitions. Organizing the study of the history of the exploration of Russia’s northern territories and popularizing the first voyages along the Northern Sea Route will help to increase interest in the history of the exploration of the northern territories of the Fatherland. The exploration of the shores and islands of the Arctic seas by pioneers should evoke a sense of pride in the younger generation for the courage of our people and the greatness of our country. Arctic museums located in this territory play an important role in the preservation, study and popularization of the cultural and natural heritage of the Russian North. At the same time, their increased participation in the development of tourism activities will contribute to their modernization and development.

Thus, the prospects for further comprehensive development of the northern and Arctic territories of Russia should be linked not only to the development of the extractive complex of the economy, but also to the cultural and natural heritage of the territories, using the potential of museum exhibitions and promoting them to a wide audience both in Russia and abroad .