Extra-role performance behavior of teachers: the role of identification with the team, of experience and of the school as an educational organization

Автор: Klimov Aleksei Aleksandrovich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Young researchers

Статья в выпуске: 6 (36) т.7, 2014 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article discusses extra-role performance behavior of teachers and their identification with the teaching staff under the conditions of modernization of the education system and optimization of the network of educational institutions in Russia. The author provides a review of the literature on the subject and specifies the concept of extra-role performance behavior of teachers, what factors cause or promote such behavior, and what it means to be a “good teacher”. Understanding the importance of extra-role performance behavior as an essential component of labor efficiency will help educational organizations’ heads to use it in the recruitment, selection and certification of teachers, and in the development of personnel reserve. The author selects three factors predicting extra-role performance behavior: work experience, the school as an organization, and identification with the school staff. Regression models based on data on school teachers of Vologda (N = 78.6 schools), explained extra-role performance behavior associated with a change in the functioning of the organization (Model 2...

Extra-role performance behavior, identification with the organization, work experience, "good teacher", labor efficiency, educational organization, modernization of education

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223675

IDR: 147223675 | УДК: 371.12 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2014.6.36.19

Текст научной статьи Extra-role performance behavior of teachers: the role of identification with the team, of experience and of the school as an educational organization

For more than two decades organizational identity, along with the construct of organizational identification have become two of the most significant concepts of the research in organizations and their management [15], but they are rarely used in the study of school education. The purpose of the study is to understand how much teachers feel identified with their work and the team, to predict, if possible, the effectiveness of their activities (extrarole behavior) in terms of the challenges faced by the modern school.

The first task is to describe the current situation at higher education institutions and possible consequences of education modernization for teachers’ identification with their school staff. The studies show that organizational identification generates a wide range of positive consequences for an individual employee and for the organization as a whole: low level of dismissals, civic behavior in the organization, job satisfaction and subjective well-being, productivity growth [8; 32].

Therefore, maintaining a high level of identification with the profession, the working group and the organization as a whole becomes an important task of modern management.

We would study whether this is true in the case of teachers’ identification with school staff.

The second task is to reveal the importance of studying extra-role behavior as a measure of teachers’ labor efficiency and one of the consequences of identification. The number of researches in extra-role behavior at school is not great not only in Russia. It is also typical for the United States, where on the background of sharply increasing popularity of research in extra-role and civic behavior in the organization “before 2006 only one study in the sphere of education was conducted” (cit. [25]).

Researchers consider extra-role behavior as critical for the survival of organizations in the crisis periods, caused by the changes [38], that is why its study becomes more relevant in times of changes.

Extra-role behavior in the organization

Organizational psychologists, drawing attention to the fact that labor productivity is a multicomponent phenomenon, have focused on individual aspects of organizational behavior that goes beyond the traditional patterns of quantity or quality of task performance [29]. The extended definition of the employee’s effectiveness includes consideration of the fact that in addition to his/her duties he/she is free to act for the good of the organization. The research is conducted in three directions [3]: 1) to study what behavior can be considered as extra-role in certain circumstances; 2) to study factors, which cause or aggravate it; and (3) to study its consequences for an employee and the organization.

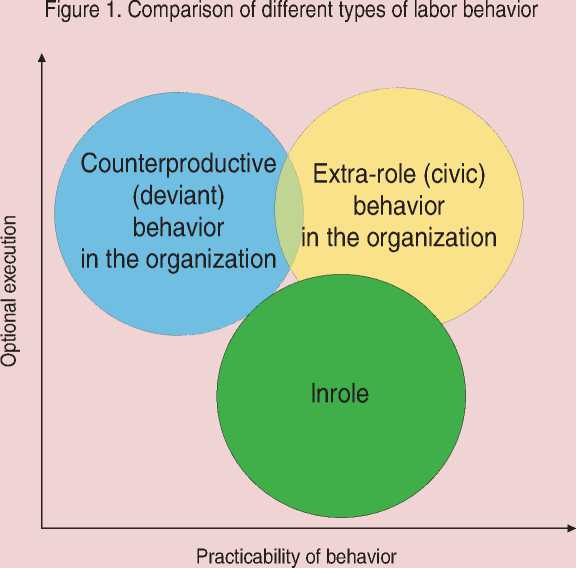

Extra-role behavior or civic behavior in the organization is one of the types of prosocial behavior, corresponding to three criteria: 1) it is arbitrarily regulated by employees and depends on their desires; 2) it is not taken into account by the formal reward system in the organization; 3) it makes benefit to the organization [28]. Since the control and regulation have natural limitations, people largely choose how to behave in accordance with their personal characteristics, expectations of colleagues and the wider environment. Helping and supporting colleagues, participating in public events as extra-role actions are desirable and beneficial for organizations, unlike counterproductive behavior (fig. 1): spreading rumors, damaging the property deliberately, simulating sickness, etc.

“Role expectations” serve as an indicator that differentiates between extra-role and in-role behavior [6]. They can be defined by group norms [6; 36], and individual motivation [37]. According to the latter, people behave in some way, if [37]: they feel that they will achieve the goal due to their efforts; the goal will be rewarded; the reward is important for an individual.

Despite the fact that compensation is not provided for extra-role behavior, many employees show it, as apart from the benefit to the organization this behavior is advantageous for an employee.

The researchers note that extra-role behavior:

-

• Affects an employee’s assessment by managers (when they try to assess a person, they rely on objective performance indicator by 9.5% and on extra-role behavior by 42.9% [29, pp. 536, 537]); and by colleagues who treat better those who show extra-role behavior.

-

• Associated with the probability of employment, with the decision-making on the distribution of material resources of the enterprise and the salary increase. Those who show extra-role behavior, often receive bonuses (rc=0.77), get a higher salary than their colleagues (rc=0.26) [28].

The role of extra-role behavior increases when [25]:

-

> The objective evaluation of the activity is difficult. Teaching is a very complex and multi aspect activity where connection “input-process-outcome” is not precisely defined. None of the methods to evaluate teachers’ work (observation of teaching a class, teachers’ self-esteem, interviews, students’ assessment of teachers, students’ academic achievement) is accurate taken apart [4] or together [17; 23], as it interferes with a lot of side variables, which are difficult to consider.

The role expectations prevail in such conditions. They largely depend on the teachers’ image at school and their experience. As there is no penalty for failure to carry out extra action, teachers act “on their own” or when they “are required”.

-

> The learning and teaching activities are associated with moral values. Inclination and persistent commitment to teaching are mainly of emotional nature. Therefore, such employees have always been very altruistic, and therefore, they will worry about their colleagues more than others, help them and try to ensure the survival of their school as an organization.

The survey that has included 50 interviews of Israeli teachers and 20 school administrators (headmasters and head teachers) discloses a portrait of a “good teacher” showing extrarole behavior ( tab. 1 ).

Even in cases where the scale is developed specifically for the study of school teachers [34], the factor structure remains the same as a whole: behavior aimed at colleagues and the organization as a whole. The specific component is added – behavior aimed at students at school and at customers at enterprises.

Context of the education reform

The early attempts (until 1997) to intervene in school education were ineffective around the world. After analyzing 15 examples of education reforms [13], American researcher of educational innovations M. Fullan concludes that in the USA most major reforms of school education have failed and school performance has not improved [12]. “In 1980–2005 public expenditure per student in the United States increased by 73%, with inflation being taken into account”, but the target indicators did not enhance [21, p. 8].

Table 1. Examples of teachers’ extra-role activities

|

Objects |

Examples of activities |

|

Single pupil |

Work with pupils in additional time Help a pupil deal with stress Provide care, making it proactive |

|

Work with class |

Initiate and implement changes in the program Carefully check homework Participate in extracurricular activities of the class |

|

Colleagues |

Share teaching materials with colleagues Exchange professional experience Help colleagues solve administrative tasks Be responsive and sympathetic |

|

School organization |

Participate in school activities and events Participate in the work of school committees Take unpaid school responsibilities |

|

Provided by: Oplatka I. Going Beyond Role Expectations: Toward an Understanding of the Determinants and Components of Teacher Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Educational Administration Quarterly , 2006, no. 3, vol. 42, pp. 385-423 |

|

Speaking about the presence of significant progress in 2003–2009, M. Fullan suggests that the following changes occurred in the global educational space (cit. [12]):

-

1. Wages (especially for beginners, during the first 10 years) will grow, along with demands on teachers.

-

2. Unification of achievement tests will be developed; general strategies for different regions will be elaborated.

-

3. Demand for teachers’ leadership skills will grow, because to a greater extent the funding will be allocated to those who can meet the highest standards and can “promote” them, seeking more.

The education reform in Russia corresponds to all these modern trends; due to it our education system has come a long way and nowadays it ranks 5th among the OECD member states by the pace of development [24]. Financial incentives for teachers are a fundamental factor to attract skilled young people to school [21; 24].

In accordance with the purposes of the developed “roadmap” the load of high school teachers1 is expected to increase by 18% [1, p. 49] and school teachers – by 9.4% [1, p. 18]. The main cause of a number of negative consequences that teachers experience – psychological burnout, stress and reduced commitment to work – is great work load, which amounts to about 50 hours a week. Even if we consider time required to teach a class, check homework and tests and plan lessons, teachers spend 44% of their time for the rest of the tasks [27].

The increased load can lead to a variety of compensation strategies [27]: teachers begin to spend less time on self-development, their career ambitions reduce.

However, those teachers who have time for additional education, reading professional literature, school projects are emotionally healthy.

Organizational identification

According to John Turner’s theory of social identity, the mechanism of social identification with the group is selfcategorization as a member, which emphasizes the perceived or possible similarities between members within the group and makes a clear distinction between their own and other groups [20, p. 317], promotes a positive “self-concept”. This is a basic definition, accepted by all researchers of social identification. For the first time B. Ashforth and F. Mael suggested using the explanatory potential of “identification with the group” with regard to the study of social identity in the enterprise.

Considering organizational identification as a specific form of social identification [in translation 7; 9], these scientists define it as “perception of similarity or belonging to an organization when an individual defines himself/herself in terms of the organization he/she is a member” (cit. [5, p. 137]).

There are several points of view on the structure and types of organizational identification.

According to the first one, as organizational culture of each organization is specific, organizational identification is fundamentally unique. Not only between organizations but also within the organization there can be several subcultures (working groups, etc.). The study of Pratt and Foreman, supporting this approach, indicates that “the organization always has multiple organizational identities, depending on what is central, peripheral and specific in the organization” [15; 30, p. 20].

The second one indicates that the structure of organizational identification is practically the same in organizations of different types (from a school to a call center) [35].

We agree with the second point of view: structure identification does not change fundamentally in different activities. If so, organizational identification, being a reliable predictor of various forms of extrarole behavior in business organizations [29; 31], will predict it among school teachers. This means that the higher the level of teacher’s identification with school staff is, the more likely he/she will show extrarole behavior. The role of experience still remains unclear [26; 29; 38], it is possible that this relation is valid only for beginners or only for teachers working long at school.

Experience

Experience is considered as a cause or as a consequence of organizational identification in different studies. It is seldom considered as a mediator between a response variable and organizational identification [32].

The working period in the organization and organizational identification correlate moderately (rc=0.13-0.16) [32], but in some studies they correlate negatively [10, p. 450].

In particular, according to J. Meyer, employees who have already gained professional skills can be in a better position (in terms of remuneration, quality of work) than their younger, less experienced colleagues who can stay in the organization because they are afraid of dismissal. This connection becomes even more complicated if we consider the age [22].

In this case, the reason for young employees to work in the enterprise is not organizational identification but the fear not to find work elsewhere. Newcomers with low emotional attachment do not tend to visit the loyalty enhancement programs [16].

The study of Israeli teachers has revealed that at their level of civic behavior there is no difference between those who have worked at the same school less than 9 years or more; those who were younger or older than 44; those who have worked in education up to 15 years and more; and even among those who were on temporary and permanent contract [38].

There is another point ofview: teachers spend their time, according to their experience and image at school [27].

It seems to us that newcomers have less time and opportunity to influence school organization and help colleagues.

Therefore, the level of extra-role behavior should correlate with experience, but this relation can be nonlinear.

Research methodology

The sample2 of our study was 78 people (4 men, 74 women) from 6 schools in the city of Vologda, aged 20–64, the average age was 37 (SD=12.2). Sixty-two respondents get higher education. The average professional work experience amounts to 10 years.

After the respondents were informed that their data would be taken as a whole (anonymously), they completed a number of questionnaires in the presence of the experimenter:

-

1. Extra-role behavior was measured by the method of B.G. Rebzuev [6]. It contains 12 statements, grouped into three scales by four points: a) performance enhancement (for example, “Improve the work process, so that it could be done better or faster”); b) overtime work (for example, “Come to work on weekends or work at home”); c) helping the colleagues (for example, “Help a colleague who has a lot of work”). In accordance with the instructions, the respondents assessed how often they performed the above activities from 1 (“never”) to 7 (“always”). For each scale and the total indicator the scores for the answer to each question were added and divided by the number of questions.

-

2. Organizational identification with school staff was measured using the method of “a five-factor model of identity” [2]. It consists of 14 statements, forming 5 scales: (a) self-stereotypization (for example, “I look like an average school employee”); (b) ingroup homogeneity (for example, “All employees of the school are very similar to each other”); solidarity (for example, “I feel involved with school staff”); d) satisfaction (for example, “I think that school employees have reasons to feel proud”); d) centrality (for example, “Belonging to the school staff is an important part of my self-image”). The respondent was to agree with each statement according to a 7-point scale from 1 (“absolutely disagree”) to 7 (“absolutely agree”).

-

3. The perceived school integrity was measured by the GEM graphical method (the Group Entitativity Measure) [14].

For each scale and the total indicator the scores for the answer to each question were added and divided by the number of questions.

Results

Extra-role behavior of teachers . In the group of school teachers extra-role behavior ( x =4.25, sd =0.85, N =78) is more vivid than that of employees at Saint Petersburg enterprises ( x =3.88, sd =1, N =201 ) [6, p. 35]. The average effect rate ( t =3.11, df =164.05, p =0.002, d Cohen=0.39) is found out; this means that 65% of the teachers in our sample have an indicator higher than the average of the standardization sample.

Only the scale “Overtime work” has significant differences, therefore, it can be assumed that teachers cover for their colleagues and stay at work more often than representatives of business organizations.

Teachers’ identification with school staff . The method of the “five-factor model of identity” has not been specifically validated by the sample of teachers, so we tested its psychometric indicators. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) method measuring identification showed that the sample of teachers has satisfactory results.

The model, which best described the data obtained, had satisfactory quality indicators (df=71, RMSEA=0.13, CFI=0.87, x2=168.02, AIC=2919.94, BIC=3033.06). It corresponds to other studies, indicating that “Model 5” [2] or “Model A” [18] is the best model on the basis of religious, ethnic and other social identities. It unites, as in our case, the scales “satisfaction”, “solidarity” and “centrality” in the latent factor “personal contribution” and the scales “self-stereotypization” and “ingroup homogeneity” in the factor “personal identity”. This suggests that the factor structure of teachers’ identification with the staff is, in general, the same as in other social groups, and this method can be used to diagnose identification in the group of teachers.

The method adapted for the Russian language was published in 2013, so there are not many researches using it nowadays. Though there are many foreign studies of organizational identification, including in the sphere of higher education (identification of students with their universities, professors with departments, etc.), we have not found out special domestic or foreign studies of school teachers that use the same method to diagnose identification. Therefore, for comparison, it is possible to use data from other spheres, such as employees’ identification with their organization. L. Smith used the factor “personal contribution” from the “five-factor model” within 6 months in the study of large companies [33]. In comparison with her data ( N =471), teachers (hereinafter, N =78) are significantly less satisfied with their membership in the school group ( t =-5.7, df =104.6, p <0.001, d Cohen=-0.69); at the same time, solidarity ( t =-0.45, df =112.61, p =0.651, d Cohen=-0.05) and centrality do not differ ( t =-0.11, df =108.47, p =0.91, d Cohen=-0.01). So, though they are dissatisfied with their membership in this group, they communicate with their colleagues and consider school staff as

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and a correlation matrix, teachers of Vologda schools (N=78)

|

Mean |

SD |

Cronbach’s |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

1. Sex |

0.05 |

0.22 |

— |

— |

||||||||

|

2. Age |

37.37 |

12.20 |

— |

-0.17 |

— |

|||||||

|

3. Experience at a concrete school |

9.80 |

9.81 |

— |

-0.06 |

0.69*** |

— |

— |

|||||

|

4. Perceived integrity |

4.38 |

1.13 |

— |

0.04 |

-0.23* |

-0.37*** |

— |

|||||

|

5. Organizational identification |

5.09 |

0.83 |

0.91 |

-0.15 |

0.04 |

-0.08 |

0.25* |

— |

||||

|

6. Extra-role behavior: |

3.64 |

0.73 |

0.82 |

0.13 |

0.16 |

0.33** |

-0.18 |

0.09 |

— |

|||

|

7. Performance improvement |

3.65 |

1.20 |

0.82 |

0.15 |

0.14 |

0.33** |

-0.28* |

-0.12 |

0.77*** |

— |

||

|

8. Overtime work |

4.50 |

1.06 |

0.53 |

0.05 |

0.20 |

0.21 |

-0.01 |

0.22* |

0.74*** |

0.30** |

— |

|

|

9. Helping colleagues |

4.60 |

0.96 |

0.67 |

0.13 |

0.02 |

0.22 |

-0.13 |

0.09 |

0.83*** |

0.49*** |

0.53*** |

— |

|

Note. Mean is an average score, SD is standard deviation. Age was pointed out in years; gender was coded as follows: 0 for women and 1 for men. To calculate the correlation coefficients we used Spearman’ p : *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. |

||||||||||||

an important social group (it plays the same important role in the social identity structure). In other words, the structure of teachers’ identification does not have other features, except for low satisfaction with group membership.

Connection between extra-role behavior and identification with school staff . Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations between the study variables. The only variable indicating extra-role behavior is experience in this school p -Spearman=0.33; p =0.003). Identification with school staff and perceived integrity predict extra-role behavior much worse.

Linear modeling. To test hypotheses about connection between extra-role behavior and identification we have developed linear models that take into account the multilevel nature of our collected data. It should be noted that some variations of extra-role behavior (and other variables) can be determined not by the predictors, but by the school where a teacher works.

The features of the school community, organizational culture and other parameters are given below.

Multilevel linear modeling requires fulfilling a number of conditions, which in our case are met partially. Due to these limitations the school level is included in the model in the categorical form (the schools characteristics were not considered).

The groups of built models presented in table 3 were obtained using the least-squares estimate. In the heading of table 2 the output variable (the independent variable) is specified for each model. It ranges from 1 – “absolutely never to 7 – “always”. The lines reflect the values of non-standardized beta coefficients of the predictors: the positive value is growth of extra-role behavior components, the negative value – their decrease. Experience and age were coded in years.

Table 3. Communication components of extra-role behavior and identification, teachers of Vologda schools (N=78)

|

Predictor |

Model 1. Extra-role behavior |

Model 2. Enhancement of performance |

Model 3. Overtime work |

Model 4. Helping the colleagues |

|

Free member |

3.40 (0.79)*** |

3.26 (1.09)*** |

2.88 (1.01)*** |

4.07 (0.88)*** |

|

Experience at a concrete school |

0.03 (0.02)* |

0.05 (0.02)* |

0.02 (0.02) |

0.03 (0.02)* |

|

Age |

0.00 (0.01) |

-0.01 (0.02) |

0.01 (0.02) |

-0.01 (0.01) |

|

Solidarity |

0.11 (0.15) |

0.26 (0.21) |

0.03 (0.20) |

0.04 (0.17) |

|

Satisfaction |

0.04 (0.15) |

0.18 (0.21) |

-0.07 (0.19) |

0.01 (0.17) |

|

Centrality |

-0.13 (0.13) |

-0.42 (0.18)** |

0.10 (0.17) |

-0.06 (0.15) |

|

Self-stereotypization |

-0.03 (0.13) |

-0.22 (0.19) |

0.13 (0.17) |

-0.01 (0.15) |

|

Ingroup homogeneity |

0.10 (0.12) |

0.22 (0.17) |

-0.01 (0.16) |

0.08 (0.14) |

|

R2 |

0.17 |

0.21 |

0.12 |

0.19 |

|

Adj. R2 |

0.03 |

0.07 |

-0.03 |

0.06 |

|

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01. |

||||

Table 4. Connection between extra-role behavior, identification and experience for teachers of Vologda schools (N=78)

|

Predictor |

Model 5. Extra-role behavior |

|

Experience at a concrete school |

0.55 (0.21)** |

|

Age |

-0.21 (0.18) |

|

Identification |

0.08 (0.11) |

|

Age: Experience |

-0.18 (0.10)* |

|

Identification: Experience |

0.26 (0.13)** |

|

R2 |

0.16 |

|

Adj. R2 |

0.10 |

The percentage of variation explained of extra-role behavior components varies from 0.12 to 0.21. In Model 4 experience accounts for 9.6%, identification compo-nents – 1.6%, group level or variation by schools – 5.8%.

However, the greater the experience is, the greater the frequency of extra-role behavior, the age impact is almost not noticeable.

The connection of various components of identification with the school staff with various kinds of extra-role behavior is ambiguous; sometimes it intensifies them and sometimes weakens.

The sample size does not allow us to draw conclusions, leaving the possibility for further research.

The final model development requires the assessment of not only the role of identification components, experience and age as predictors, but their interaction with each other. For it we included the overall indicator of extra-role behavior as a dependent variable, three variables (overall identity, experience, age) as predictors and interaction between them.

Then, excluding variables and/or interactions between them from the model one by one, we selected the best model based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

Table 4 discloses Model 5; it has an improved adjusted R2, compared to Model 1. The standardized beta coefficients allow us to compare the contribution of variables in different dimensions on the basis of their standard deviation (see column SD in tab. 2).

Let us consider a few examples of interaction in contrasting groups:

-

• If you compare two teachers (aged 25 and 46), who has worked at the school for 3 years, the young teacher will more often show extra-role behavior (this effect is negligible (9.3%) and is compensated by experience).

-

• Out of two teachers of the same age (aged 37) with a middle level of identification the teacher who has worked at school for 3 years will show extra-role behavior less frequently (about 20%) than the teacher who has worked for 16 years.

-

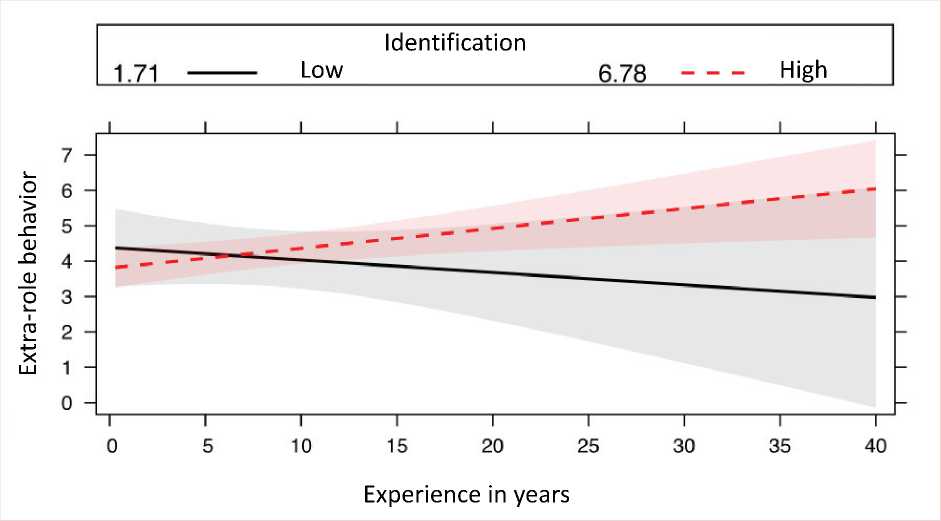

• The probability of extra-role behavior increases by 2.6% if the teacher aged 37 having worked for 10 years at school has a high level of identification; in the future this effect becomes even more vivid (see fig. 2).

Figure 2. Extra-role behavior of school teachers, connection between experience and identification with school staff

Conclusions

The teachers’ identification with school staff is characterized by low satisfaction with group membership. The elimination of boundaries between working and nonworking time leads to low job satisfaction and psychological burnout. The structure of identification with school staff is similar to identification with other social groups.

The teachers’ working day is not regular. He/she spends much time not only on teaching a class, preparing for lessons and checking homework, but on extra-role activities. The Vologda teachers show this behavior more actively than employees at enterprises. Increased loads presuppose decrease in these indicators. Extra-role behavior is an important component of labor productivity; therefore, the administration of educational organizations should pay attention to it during recruitment and assessment, for example, during employee rating, personnel reserves formation.

Best of all extra-role behavior is predicted by experience; the second most important factor is the school where the teacher works; the identification components have the weakest predictive ability. Many programs (formation of a personnel reserve, promotion of loyalty) are aimed at keeping the highest quality employees by means of financial incentives and adherence to the team. This leads to the increased demands for beginners. But it should be noted that young employees find it difficult to show their extra-role activity; therefore, work productivity of newcomers (expressed in growth of extra- role activity) can not increase immediately. Such programs often have a delayed effect.

In accordance with the obtained data about extra-role behavior of Vologda school teachers, we can give the following recommendations to consider in the human resource policy:

-

1. Experience largely determines whether teachers will act for the good of the school community on their own. Preference is given to those who have worked in the school system for a long time.

-

2. The role of identification develops in about 10 years: if by this time stable positive commitment to the school team has not been formed, one can expect a significant reduction in extra-role activities.

-

3. Recommendation of younger employees to the personnel reserve only according to their age makes no sense. The long-term prospects should be taken into account: if a teacher plans to work at school long (the effect of experience will be pronounced) and the personnel reserve program can strengthen his/her identification, the visible differences in extra-role behavior will appear not earlier than in a few years.

The education reform, leading to the increase in teachers’ load, can lower their extra-role behavior (see tab. 1), influence the willingness to be a “good teacher” and result in the launch of unproductive compensation strategies. The effects can be delayed (during 10 years) that requires careful planning changes. The beginners’ low level of identification with school staff

(especially in terms of satisfaction) can cause a decrease in their extra-role behavior in the future. So, today it is necessary to take appropriate measures to maintain a high index of extra-role behavior of those who have worked at school for a long time.

Список литературы Extra-role performance behavior of teachers: the role of identification with the team, of experience and of the school as an educational organization

- Ob utverzhdenii plana meropriyatii (“dorozhnaya karta”) “Izmeneniya v otraslyakh sotsial’noi sfery, napravlennye na povyshenie effektivnosti obrazovaniya i nauki”: rasporyazhenie Pravitel’stva Rossiĭskoĭ Federatsii ot 30 aprelya 2014 g. № 722-r . Rossiĭskaya gazeta , 2014, May 8. Available at: http://www.rg.ru/2014/05/08/nauka-site-dok.html (accessed: August 15, 2014).

- Agadullina E.R., Lovakov A.V. Model’ izmereniya ingruppovoi identifikatsii: proverka na rossiiskoi vyborke . Psikhologiya: zhurnal Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki , 2013, vol. 4, no. 10, pp. 143-157.

- Gulevich O.A. Grazhdanskoe povedenie v organizatsii: usloviya i posledstviya . Organizatsionnaya psikhologiya , 2013, vol. no. 3, pp. 2-17. Available at: http://orgpsyjournal.hse.ru/2013-3/117908674.html (accessed: August 15, 2014).

- Zagvozdkin V. Ekspertiza uchitel’skogo truda za rubezhom . Obrazovatel’naya politika , 2011, no. 1, vol. 51, pp. 111-117.

- Lovakov A.V. Sovremennye tendentsii v issledovaniyakh organizatsionnoi identifikatsii . Psikhologicheskie problemy sovremennogo biznesa Ed. by N.V. Antonov, N.L. Ivanov, V.A. Shtroo. Moscow: Izdatel’skii dom NIU VShE, 2011. Pp. 135-159.

- Rebzuev B.G. Razrabotka konstrukta trudovogo povedeniya i shkaly ekstrarolevogo trudovogo povedeniya . Psikhologiya: zhurnal Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki , 2009, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 3-57.

- Ashforth B.E., Mael F. Teoriya sotsial’noĭ identichnosti v kontekste organizatsii . Organizatsionnaya psikhologiya , 2012, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 4-27. Available at: http://orgpsyjournal.hse.ru/2012-1/50605114.html (accessed: August 15, 2014).

- Ashforth B.E., Harrison S.H., Corley K.G. Identification in Organizations: An Examination of Four Fundamental Questions. Journal of Management, 2008, no. 3, vol. 34, pp. 325-374.

- Ashforth B.E., Mael F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. The Academy of Management Review, 1989, no. 1, vol. 14, pp. 20-39.

- Blader S.L., Tyler T.R. Testing and Extending the Group Engagement Model: Linkages between Social Identity, Procedural Justice, Economic Outcomes, and Extrarole Behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2009, no. 2, vol. 94, pp. 445-464.

- Cohen J. A Power Primer. Psychological Bulletin, 1992, no. 1, vol. 112, pp. 155-159.

- Fullan M. Large-Scale Reform Comes of Age. Journal of Educational Change, 2009, no. 2-3, vol. 10, pp. 101-113.

- Fullan M., Pomfret A. Research on Curriculum and Instruction Implementation. 1977.

- Gaertner L., Schopler J. Perceived Ingroup Entitativity and Intergroup Bias: An Interconnection of Self and Others. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1998, no. 6, vol. 28, pp. 963-980.

- He H., Brown A.D. Organizational Identity and Organizational Identification: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. Group & Organization Management, 2013, no. 1, vol. 38, pp. 3-35.

- Klein H.J., Weaver N.A. The Effectiveness of an Organizational-Level Orientation Training Program in the Socialization of New Hires. Personnel Psychology, 2000, no. 1, vol. 53, pp. 47-66.

- Lavy V. Performance Pay and Teachers’ Effort, Productivity, and Grading Ethics. American Economic Review, 2009, no. 5, vol. 99, pp. 1979-2011.

- Leach C.W. et al. Group-Level Self-Definition and Self-Investment: A Hierarchical (Multicomponent) Model of In-Group Identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2008, no. 1, vol. 95, pp. 144-165.

- Lenth R.V. Some Practical Guidelines for Effective Sample Size Determination. American Statistician, 2001, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 187-193.

- Levine J.M., Hogg M.A. Encyclopedia of Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. Sage Publications, Inc, 2010.

- McKinsey. How the World’s Best-Performing School Systems Come Out on Top. Available at: http://mckinseyon-society.com/how-the-worlds-best-performing-schools-come-out-on-top/.

- Meyer J.P., Allen N.J. A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1991, no. 1, vol. 1, pp. 61-89.

- Nusche D. et al. Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment. OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, 2013.

- OECD. Measuring Innovation in Education: A New Perspective, Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing, 2014.

- Oplatka I. Going Beyond Role Expectations: Toward an Understanding of the Determinants and Components of Teacher Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Educational Administration Quarterly, 2006, no. 3, vol. 42, pp. 385-423.

- Organ D.W., Ryan K. A Meta-Analytic Review of Attitudinal and Dispositional Predictors of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Personnel Psychology, 1995, no. 4, vol. 48, pp. 775-802.

- Philipp A., Kunter M. How do Teachers Spend Their Time? A Study on Teachers’ Strategies of Selection, Optimisation, and Compensation over Their Career Cycle. Teaching and Teacher Education, 2013, vol. 35, pp. 1-12.

- Podsakoff N.P. et al. Individual-and Organizational-Level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2009, no. 1, vol. 94, pp. 122-141.

- Podsakoff P.M. et al. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: A Critical Review of the Theoretical and Empirical Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. Journal of Management, 2000, no. 3, vol. 26, pp. 513-563.

- Pratt M.G., Foreman P.O. Classifying Managerial Responses to Multiple Organizational Identities. Academy of Management Review, 2000, no. 1, vol. 25, pp. 18-42.

- Riketta M., Dick R.V. Foci of Attachment in Organizations: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of the Strength and Correlates of Workgroup versus Organizational Identification and Commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 2005, no. 3, vol. 67, pp. 490-510.

- Riketta M. Organizational Identification: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 2005, no. 2, vol. 66, pp. 358-384.

- Smith L.G. et al. Getting New Staff to Stay: the Mediating Role of Organizational Identification. British Journal of Management, 2012, no. 1, vol. 23, pp. 45-64.

- Somech A., Drach-Zahavy A. Understanding Extra-Role Behavior in Schools: The Relationships between Job Satisfaction, Sense of Efficacy, and Teachers’ Extra-Role Behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education, 2000, no. 5, vol. 16, pp. 649-659.

- Van Dick R. et al. Identity and the Extra Mile: Relationships between Organizational Identification and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. British Journal of Management, 2006, no. 4, vol. 17, pp. 283-301.

- Van Dyne L., LePine J.A. Helping and Voice Extra-Role Behaviors: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity. Academy of Management Journal, 1998, no. 1, vol. 41, pp. 108-119.

- Van Eerde W., Thierry H. Vroom’s Expectancy Models and Work-Related Criteria: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1996, vol. 81, no. 5, pp 575-586.

- Vigoda-Gadot E. et al. Group-Level Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Education System: A Scale Reconstruction and Validation. Educational Administration Quarterly, 2007, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 462-493.