Fan culture and its influence on footbol: insights from Croatian supporters

Автор: Ferenčić M., Čehulić L.

Журнал: Sport Mediji i Biznis @journal-smb

Статья в выпуске: 2 vol.11, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This paper examines the culture of sports fans, focussing on fans' habits, their influence on sport, the psychology and methods of cheering, fan types and their motivations. The main objectives of the paper are to show what drives fans, their loyalty and other factors that influence their engagement, especially with football clubs. The study compares fan groups across Europe and highlights the main differences. It also analyses the motivations of Croatian fans, including regular attendance and club loyalty. In order to collect data on fans' habits and attitudes, a quantitative survey was conducted, looking at sports preferences, frequency of attendance, spending, involvement in deviant behaviour and the importance of club success. The results show that most Croatian fans follow football, have supported their club for over 15 years and usually go to matches several times a year. The strongest motivations are love, a sense of belonging and the integration of the club as part of the fan's identity. Creative songs and banners as well as charity work are important features of this identity. Strengthening relationships between fans and clubs and expanding the regional focus form a strategic basis for sports clubs to increase the number of fans.

Fan culture, sports fans, emotional attachment, fan psychology, fan motivation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170211101

IDR: 170211101 | УДК: 796.073; 316.647:796.332; 316.723 | DOI: 10.58984/smb2502047f

Текст научной статьи Fan culture and its influence on footbol: insights from Croatian supporters

DOI:

Sport is now a globally popular activity for all groups, influencing public opinion, consumer behaviour, lifestyle and health through modern technologies and media, leading to an increase in family spending on sport-related activities (Ratković, Kavran and Zolak, 2022). Sports are enjoyed both individually and in groups, while professional sports and competitions are often consumed in large groups, commonly referred to as fan groups (Funk, Alexandris & McDonald, 2022). The behaviour of fan groups varies greatly and differs significantly from country to country. The experiences and meaning of football and football matches differ not only between fan groups and ordinary fans, but also between Eastern and Western Europe. According to Dr Andrew Hodges, a social anthropologist from Manchester, fan groups can be divided into subcultures (where the focus is on uniqueness) and political movements (where the focus is on politics).

In order to understand these differences, this article analyses the attendance figures for handball, basketball and football matches and examines the question of how sports fans are described and what drives them to become fans. To better understand Croatian sports fans behaviours research has been conducted, focusing on football fans.

Sport fans – who are they and what motivates them?

Turković (2016: 13) defines fans as "people who gather in groups and cheer on their team at matches, with or without aids, to support the team in achieving positive results. It is a heterogeneous group that is part of the sports audience and forms an unstructured and unorganised social group.”

Regarding motivation, Funk, Alexandris, and McDonald (2022) describe two types: intrinsic (participating for learning, achievement, fun, or new experiences) and extrinsic (participating for results, rewards, or from guilt/anxiety). Shilbury et al. (2009), on the other hand, identify five fan motives that motivate fans to attend sporting events: socialisation, performance, excitement, respect and entertainment. The authors emphasise that fans differ from normal spectators due to their deep psychological need for connection and a sense of belonging.

Fans can also be categorised according to their level of involvement: occasional, moderate or fanatical (Bang and O'Connor, 2022). Fanatics are the most emotionally involved as they empathise strongly with their team's victories and defeats, as Bang and O’Connor (2022) explained, and are seen as important supporters by the teams.

Whitbourne (2011) describes two patterns of sports fans’ reactions to their team’s performance. The first is “BIRGing” from Basking in Reflected Glory. When the team wins, fans feel great. Author further explains that different research shows that fans feel even better the next day. They say “we” won, identifying strongly with the club, and are more likely to wear team merchandise after a victory. The second pattern is “CORFing” from Cut Off Reflected Failure. When the team loses, fans distance themselves from the loss, saying “they” lost, not “we.” CORFers avoid wearing team items after a defeat. This difference reveals true fans versus fair-weather fans, whose team identification rises and falls with results. True fans continue to show support, wearing team gear regardless of performance (Whiteborn, 2011). Additionally, sports fans are often superstitious, believing their actions—like wearing certain clothing or following rituals—can influence the outcome of games (White-born, 2011).

According to a recent study by the European Club Association (2020) on football fan behavior, there are six fan types: Football Fanatics, Club Loyalists, Icon Imitators, FOMO (Fear of missing out) Followers, Main Eventers, and Tag Alongs. Study explains Football fanatics (11%) are primarily motivated by love for the game—they follow all of football with strong emotions, frequently attend matches for a sense of community, and believe clubs should help make the world better. Club loyalists (14%) are long-time fans deeply connected to their club, following high-level football for quality and community. Icon imitators (11%) are young fans who mainly support specific star players and enjoy big matches. FOMO followers (27%) watch football to stay part of conversations, preferring major teams but with less emotional involvement. Main eventers (19%) care more about the occasion than results, often older people or women who get involved around major tournaments. The last group, Tag alongs (19%), have low emotional ties and are mainly influenced by friends, family, or the national team.

In short, sports fans represent a diverse group whose motivations, commitment and emotional attachments vary widely — from deeply loyal fanatics to casual fans characterised by their personal identity, social relationships and reactions to their team’s successes and failures.

The role of fan loyality and attendance in sports club success

As already explained, the difference between fanatical fans and casual spectators is that fanatical fans almost always follow their team and attend matches much more frequently due to their strong loyalty. They support their team even when they per- form poorly, and frequent defeats do not affect them. For this reason, sports clubs value their fans and strive to 'reward' them by winning, while strengthening relationships with fan groups through marketing activities (Rotko, 2023). Rotko (2023) also explains that fans who are committed to a club’s brand support it in the long term and are more likely to buy products and attend events, significantly extending the longevity of a sports organisation. This also means that engaged fans attract more followers by sharing their experiences in their social community, which is very effective in increasing attendance at games (Rotko, 2023).

The LA Times (MacGregor, 2004) discusses the impact of fans on athletes, emphasising that the presence of a crowd can trigger a release of adrenaline in players, which can either enhance performance by returning to dominant responses, or hinder it due to increased anxiety and nervousness (ScoreVision, 2022).

Considering the influence that fans have on sport, it can be concluded that fans are a priority in the marketing strategies of sports clubs. Increasing revenue is the most common overall objective of fan engagement (Rotko, 2023), with a focus on ticket sales, sponsorship and merchandise.

Successful clubs with a strong winning tradition attract large attendances. According to Statista data, in the 2023 Premier League season, the highest average attendance was 73,504 spectators per match, with Manchester United ranking first. At the bottom, Luton Town had an average attendance of 10,830, largely influenced by infrastructure limitations, specifically the number of seats at their stadium. Considering all 20 Premier League clubs, the overall average attendance was 38,334 spectators per match .

La Liga recorded lower attendances, led by Barcelona (with 56,304 spectators). At the bottom of the table was Mallorca with an average of 20,295 spectators, giving a league average of 29,429 . In Italy, Inter recorded the highest average attendance in the 2021/22 season with 33,183 fans, while in the Bundesliga, Borussia Dortmund led the way with an average of 81,228 spectators per match, making it the most-attended football club in Europe .

Enthusiastic and loyal fans not only drive strong attendance and sustained support through emotional and social bonds but also significantly influence sports teams’ performance and club marketing strategies, making them indispensable to the longterm success and growth of sports organizations.

Fan culture across Europe

Fan cultures in Europe vary widely, reflecting diverse histories and social contexts. English football fans boast a rich heritage with deeply ingrained traditions and high match attendances, despite rising violence and hooliganism challenges (Michie & Oughton, 2005;

Spanish fans have unique customs, such as pre-match gatherings in cafes and distinctive merchandise practices, with political affiliations often intertwined with club support . With FC Barcelona and Real Madrid becoming iconic rivals, and their “El Clásico” rivalry turning into a major cultural event (https://www.hashtagspain. com/soccer-in-spains-culture-2972/).

When people talk about Italian fans, they usually refer to Ultras. Known for choreographed performances, loud chants, banners and club colours, the Ultras also created "tifos", visual representations that expressed team spirit. While Ultras enrich fan culture with their loyalty and great choreography, there are still problems such as racism and violence .

Central and Eastern European fan culture shifted after the fall of communism, moving from a politicised, state-influenced fandom to more autonomous forms of expression football-fans-identities-what-happened-over-30-years-webinar-may-14-2021-call-ends-march-15-2021/), although political and violent themes still persist, particularly in Poland and Hungary (Benedikter and Wojtaszyn, 2017; Mortimer, 2021). Izzo et al. (2014) note that football clubs in Hungary, Poland, Romania and Moldova began to seek sponsorship to generate revenue, but spectator numbers remained low and infrastructure was underdeveloped compared to Western Europe. Despite these challenges, the popularity and progress of football in Eastern Europe is evident.

Balkan supporters, especially in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, are known for their passionate yet sometimes violent fandom brothers-in-arms-the-balkan-hooligan-bonds-fuelling-violence/#), with organized groups engaging

in intense rivalries that occasionally disrupt leagues (https://www.theguardian. com/football/2015/feb/25/greece-football-suspended-crowd-violence-syriza).

Serbia’s major fan groups include Grobari (Partizan) and Delije (Crvena Zvezda, Belgrade). Delije, officially founded in 1989 from a merger of fan groups, are considered among Europe’s most powerful fan association (https://www.telegraf. rs/sport/navijaci/3022014-slala-su-se-pisma-o-ujedinjenju-svim-bitnijim-navijacima-zvezde-ili-je-to-uradio-arkan-dve-verzije-o-ujedinjenju-delija-pre-30-godina-video).

Due to geographical and historical ties, Croatian and Serbian fan groups are often compared with each other. Political and social influences were often the trigger for their confrontations. However, violent clashes between these groups have decreased in recent times .

Fan groups in Croatia

Talking about football in Croatia, Pesarović and Mustapić (2013) explain that Croatia has successfully gained a foothold in the football world mainly due to the results of its national team, but that the reality of the Croatian national league is far from the standards of the rich European leagues.

Table 1 shows the average number of spectators in the Croatian Football League over the last 10 seasons. With the exception of the 2020/21 season, when attendances were very low due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Croatian Football League has seen a gradual increase in interest and attendance.

Table 1. Average attendance in the Croatian football league

|

Season |

Average attendance |

Club with highest average attendance |

|

2014./15. |

5,371 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 21,232 |

|

2015./16. |

2,451 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 9,246 |

|

2016./17. |

2,780 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 9,377 |

|

2017./18. |

2,948 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 11,999 |

|

2018./19. |

2,732 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 11,978 |

|

2019./20. |

3,152 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 11,837 |

|

2020./21. |

1,472 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 3,929 |

|

2021./22. |

2,841 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 12,668 |

|

2022./23. |

4,084 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 15,345 |

|

2023./24. |

5,371 |

HNK Hajduk Split- 21,232 |

While Hajduk from Split is consistently at the top in terms of spectator numbers, other clubs have lower attendances. Dinamo Zagreb, for example, had an average attendance of 3,926 in the 2021/22 season, which rose to 9,013 in the 2023/24 season due to close results and a very effective marketing campaign, especially in the spring. The Croatian club Rijeka also attracted an average of 3,799 spectators at home and away matches in the 2021-22 season, which increased to 6,406 by the 2023-24 season. The last of the four major Croatian clubs, Osijek, built a new stadium and recorded an average attendance of 7,418 in the 2023/24 season, compared to just 2,764 in the 2021/22 season besucherzahlen/wettbewerb/KR1).

This data shows a positive growth trend for the Croatian football league, with most of the growth concentrated on these four clubs, while the rest of the league is increasingly lagging behind.

Junaci (2024) discusses the return of fans to stadiums, highlighting that Dinamo has once again filled the seats, with increasing demand for tickets, especially for the home games. However, to fully understand Dinamo and its supporters, it is important to recognize the Bad Blue Boys (BBB)—the club’s iconic fan group.

The BBB are known for their passionate support, loud chants, and strong presence both at home and away matches. The group is synonymous with Dinamo’s identity in Zagreb, contributing to the club’s vibrant supporter culture and making a direct impact on the matchday atmosphere .

Dinamo has always had a large fan base, but the first organised group emerged in 1986 when some of the club’s most loyal supporters founded the Bad Blue Boys (BBB), which was modelled on foreign fan groups. The fans organised trips around what was then Yugoslavia, visiting cities such as Ljubljana, Niš and Belgrade with symbols of Dinamo, Zagreb and Croatia. There were often fights at these meetings, but the fan base grew .

In 1991, the club was renamed HAŠK Građanski, later Croatia Zagreb. Many fans rejected this and demanded the return of the Dinamo name. In the 1990s, there were riots, incidents and conflicts with the police, but when the Dinamo name returned on Valentine’s Day 2000, fan support grew back. The BBB attracted attention across Europe for their passionate support at both home and away games, but were also involved in hooliganism, earning a reputation as one of the most dangerous fan groups in Europe 25597-17-03-1986-godibbne-osnovana-navijacka-skupina-zagrebackog- .

Although the BBB is one of the most influential fan groups in Europe with many positive stories — especially in terms of charity and community support, its main shortcoming is frequent violence. . The most recent incident occurred in 2023, when BBB fans and fans of Panathinaikos Athens clashed with fans of AEK Athens, resulting in the death of Greek fan. Over 100 Dinamo fans were arrested. UEFA penalised Dinamo for the incident and the club has not had any fan support at European away matches since then hnl/klubovi/dinamo/novi-sok-nakon-poraza-u-ateni-uefa-kaznila-dinamo-15366526).

Torcida was founded in 1950 and is the oldest Croatian fan group known for its fervent support of Hajduk Split during the political oppression of the Yugoslav period, which led to the banning of the Torcida name. povijesna-cinjenica/nakon-utakmice-protiv-partizana/). Despite the ban, the fans continued to support their club. In the 1960s, incidents became more frequent. In the 1970s, Torcida adopted southern-style cheering with many flags and banners and northern-style scarf-wearing and violence .

Torcida name was re-instaled in 1981, gathering fan at the new Poljud stadium in Split. The 1980s saw political graffiti reflecting ethnic tensions and growing national consciousness, alongside rising hooliganism and drug problems (https://www. . In the 1990s the group faced crises of drugs and leadership issues . In the early 2000s, a younger generation took over, but violence continued. However, in 2004. Torcida took over managing the club Hajduk .

Croatian football is deeply characterised by its passionate fan culture, exemplified by iconic fan groups the Bad Blue Boys of Dinamo Zagreb and the Torcida of Hajduk Split. Their history reflects both deep loyalty and challenges such as violence, but despite the ongoing complexity, they continue to play a central role in maintaining and revitalising the sport.

Research into the habits and characteristics of fans in the Croatia

In order to gain a better understanding of football fans in Croatia, a research study was conducted to define their key characteristics and uncover the motivations behind their support for clubs and attendance at sporting events. The research focussed on two main relationships: the relationship between fans’ financial reso- urces and their ability to attend sporting events, and the relationship between a club's success and fans' motivation to attend stadiums, arenas and other sporting venues. The aim of the study was to investigate the reasons why fans follow certain clubs, to investigate the prevalence of deviant behaviour among fans at sporting events and to identify the club characteristics that are most attractive to Croatian fans and which they follow.

A survey-based research was conducted to achieve the above objectives. To collect the data, a questionnaire with 13 closed questions was distributed online, with the invitation to participate in the survey placed in the Dinamo fans Facebook group and other fan-based social networking groups on Instagram. This sampling strategy helped to target a specific part of the population, resulting in convenient with convenient sample but relevant sample for the topic and scope of the research. The data was collected in late 2023 and early 2024, with a total of 364 participants.

The characteristics of the sample show that significantly more male respondents took part, with men outnumbering women by 46.8 %. The largest age group was participants aged 21–30, who made up 30.2 % of the total sample. Respondents aged 31–40 made up 20.9%, followed by 41–50 year olds at 19.2%. Participants under the age of 20 made up 14.6 %, while 15.1 % were over the age of 50. In terms of educational level, the majority of respondents (55.8 %) had completed secondary school. This was followed by respondents who had completed a Master’s degree (14.6 %) and students (12.9 %). In addition, 9.1 % of the participants had a bachelor’s degree, 3.3 % had completed a postgraduate degree and 4.4 % (16 people) had only completed primary school.

The research participants are primarily interested in football. 93.4% or 340 of them stated that football is their favourite sport. This is no surprise, as the sample was selected from football fans. However, other sports are mentioned in smaller proportions: handball with 1.6% and other sports mentioned are basketball, futsal, swimming, tennis and ice hockey.

The survey results show that majority of respondents (76%) have supported their club for more than 15 years. The next largest group are those who have been fans for 10–15 years (12.1%), followed by fans who have been loyal to the club for 5-10 years (8.8%). The smallest group are the new fans, of whom only 3% have supported their club for less than five years. This question was designed to determine the degree of attachment and loyalty to a particular club. The results clearly show that most respondents have remained loyal to their club over the long term and have a deep connection with it.

Building on these findings about long-term loyalty, the study analysed the most important reasons why Croatian fans support their clubs. The majority of respondents — 50.3%— - stated that they follow their club primarily because of a strong geographical connection between the club and the region in which they live. Family influence is the second most common reason, with 11.6% stating that they cheer for a club because other family members do the same. Watching games on TV motivates 10.5% of participants to support their club, while 8.7% cited various other reasons for their loyalty. Of those who stated their personal motivations, love of the club was the most commonly cited (8.5%), followed by factors such as defiance, belonging to a fan subculture, lifestyle choice, the opportunity to participate in fan-related incidents and other individual motivations. These findings highlight the deeply rooted social, emotional and cultural drivers that characterise football enthusiasm in Croatia and reinforce the strong bonds between fans and their clubs.

The study also analysed how often fans attend their club’s matches to find out how often fans spend their time (and financial resources) inside and outside football stadiums. The survey data shows that the majority of respondents (29.8% or 108 individuals) attend their club’s matches more than five times a year. A further 23.1% attend matches once or twice a year, while 12.4% go to matches once or twice a month. Some of the respondents (9.9%) stated that they regularly attend all home and away matches, and 8.3% attend several matches per month. The remaining respondents only rarely attend matches. These results show that a significant proportion of Croatian football fans regularly attend matches.

The study analysed how much money Croatian football fans spend on attending their club’s away matches. The results show that the largest group (24%) spends between €20 and €50 on away games, 20.1% spend more than €100 per away game, 19.8% spend between €50 and €100 and 18.6% spend up to €20 on these trips. For the remaining participants, the most common reasons for not attending away games are work abroad, other personal commitments or— - for a minority — spending more than €300 per game due to long-distance travelling. These results highlight the diverse financial commitment of Croatian football fans when it comes to supporting their clubs away from home.

The study also examined the level of interest and involvement of Croatian football fans in club management and fan organisations. The results show that the majority of respondents (56.9%) are not involved in the governance or management of their club. At the same time, 39.2% of respondents said they were members of a supporters’ organisation, reflecting a strong involvement at fan community level. Only a small minority 3.9% (14 people) are directly involved as a member of their club’s board. The results suggest that while active participation in club governance is rare, a significant proportion of fans are involved in organised fan groups, underlining the importance of fan associations in Croatian football culture.

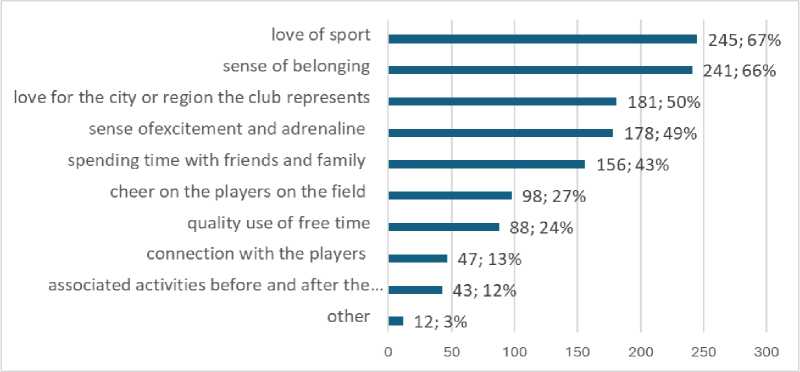

The next survey question aimed to explore the connection between fans and their clubs by identifying the reasons why respondents began supporting their particular team. Participants could select from multiple motivating factors.

The most common motivator was a love of sport, cited by 67.3% of respondents. This was closely followed by a sense of belonging, where the club is seen as an integral part of one's identity (66.2%). 49.7% of respondents stated that they support their club out of love for the city or region that the club represents. Other notable reasons include the sense of excitement and adrenaline during matches (48.9%) and the social aspect of spending time with friends and family (42.9%). The motivation to cheer on the players on the field was mentioned by 26.9%, while 24.2% felt that they could make good use of their free time. In addition, the connection with the players was an important motivation for 47 respondents, and 43 supported their club because of the associated activities and events that take place before and after the sports matches. Details are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Motivations behind Croatian football fans supporting their clubs

Source: Research results

The next question related to participation in the lighting of torches and similar activities in stadiums or arenas. The aim was to determine the frequency of deviant behaviour before, during or after matches — a widespread problem, especially in Croatian football leagues.

According to the results, the majority of respondents (66.9%) stated that they had never participated in deviant behaviour in stadiums or arenas. 24.2% of respondents admitted to having participated in such behaviour and 8.8% did not want to answer the question. This data suggests that while deviant behaviour does occur among some fans, most Croatian football fans refrain from such behaviour at sporting events.

The next question focussed on how important the success of their club is to the respondents. Only 3 respondents stated that the success of their club was not or only slightly important to them. A neutral attitude was expressed by 17 respondents (4.7%). For 59 respondents (16.3%), success was important, while the vast majority or 277 respondents (76.3%) stated that the success of their club was extremely important.

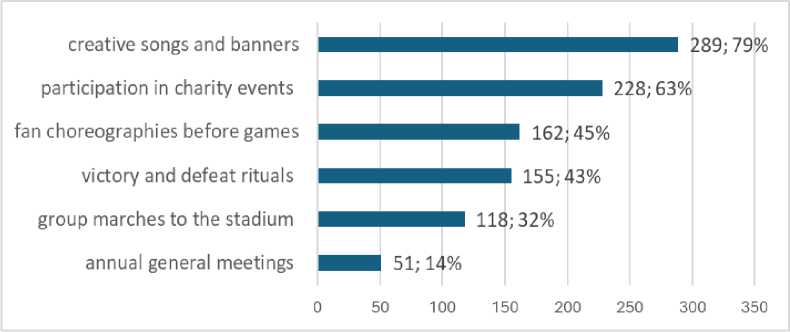

Finally, respondents were able to select multiple traditions and customs that define their fan groups. The most frequently mentioned characteristics are creative songs and banners, chosen by 80.1% of respondents, followed by participation in charity events with 63.2%. Choreographed fan shows (tifos) received 44.9% of the votes, while victory and defeat rituals were mentioned by 42.9%. In addition, group marches to the stadium were mentioned by 118 respondents and annual general meetings by 51 respondents, as shown in Figure 2.

These results emphasise the diverse cultural practises of Croatian football fans, which reinforce a strong sense of community and shared identity within their fan groups.

Figure 2. Traditions and customs characterizing Croatian football fans

Source : Research results

The study examined Croatian football supporters’ demographics, behaviors, motivations, and traditions. The sample consisted predominantly of males, mostly aged 21–30.

It is evident that a large majority of fans support their clubs for over 15 years, demonstrating strong long-term loyalty. The primary motivation for following a club is geographic connection (50.3%), followed by family influence and love for the sport. Fans frequently attend matches, with nearly 30% going to more than five games per year and typically spending between €20 and €50 on away matches. While most fans (66.9%) do not engage in deviant behaviors like pyrotechnics, a notable minority (24.2%) do. Success of the club is extremely important to 76.3% of fans, reflecting the high value placed on sporting achievement. Fan groups strongly identify with cultural traditions, notably creative songs and banners (80.1%), but also in charity involvement (63.2%) and choreographed displays (44.9%), reinforcing community bonds.

Overall, Croatian football fans show deep emotional attachment, active engagement, and rich cultural practices that sustain vibrant fan communities despite challenges.

Conclusion

It is extremely important to distinguish between general sports spectators and enthusiasts and the more dedicated fans and supporters. Due to their strong loyalty, immense motivation and deep sense of connection and belonging to their chosen club, fans are the consumers who regularly attend sporting events regardless of the cost of tickets or related stadium services. A better understanding of fans can be instrumental in driving sports marketing and popularising a wide range of sports in the European market, where football currently dominates as the most popular sport. In particular, clubs such as Manchester United and Borussia Dortmund have high attendances and generate significant revenues from ticket sales, memberships, food, drink and other in-stadium services, as well as substantial revenues from TV rights outside the stadium.

Croatian football has not yet reached this level, but is making steady progress, as evidenced by rising spectator numbers and growing interest in the league.

Fan culture, especially football fan culture, is rich and diverse throughout Europe and can look back on a long history. Cultural practises are different — for example, the traditions of English fans before, during and after matches are very different

from those of Italian Ultras— - which emphasises an important positive aspect of European sporting culture. Across Europe, fans live football and organise their daily lives around match schedules, investing money to attend away games, travelling around Europe and the world, learning about new cultures and customs — all mainly to support their club or national team. In addition, fans often take part in charitable activities.

Fans have a significant influence on sports policy and legislation, as well as other areas related to sport. Alongside the positive aspects, however, there are also negative consequences. High adrenaline levels, disappointment and anger can lead to some fans in and around stadiums being prone to riots, fights, harassment of innocent people and serious damage to property. Unfortunately, some countries have seen an increase in violence in and around stadiums, England and Wales, for example. While Turkey and Greece have longstanding problems. In Croatia, annual incidents tend to involve pyrotechnics and verbal abuse of opponents or referees, which is still an improvement on the 1990s and 2000s when brawls between fans and injuries to police and bystanders were more frequent.

Building on previous research, this paper presents a study aimed at better understanding the habits and characteristics of Croatian fans. The aim was to uncover their motivations for supporting certain clubs, investigate the prevalence of deviant behaviour at sporting events and identify the club characteristics most attractive to Croatian fans.

The results of the study show that a large majority of fans (76%) have supported their club for more than 15 years, indicating strong long-term loyalty. The most important motivation for support is geographical connection (50.3%), followed by family influence and love of the sport. Fans attend matches frequently, with almost 30% attending more than five matches per year and typically spending between €20 and €50 on away matches. While most fans (66.9%) avoid deviant acts such as the use of pyrotechnics, a minority (24.2%) admit to carrying out such acts. The success of the club is very important to 76.3% of fans, which shows how highly sporting success is rated. Fan groups are strongly associated with cultural traditions, particularly creative songs and banners (80.1%), charity events (63.2%) and choreographed performances (44.9%) that strengthen the community. These findings are consistent with previous research by Funk, Alexandris and McDonald (2022) and Shilbury et al. (2009).

In conclusion, fans and fan groups are an important factor in the operation of clubs, leagues and sport in general, exerting an influence that can have both extremely positive and extremely negative consequences. The aim of sports marketing profe- ssionals, security personnel and all stakeholders in sport should be to nurture and promote the positive aspects of the fan base whilst firmly discouraging, punishing and minimising the negative behaviours. This will help to build and develop a positive reputation for Croatian clubs, capitalise on the benefits of passionate support and turn fan engagement into successful business outcomes.

Conflict of interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions:

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.