Floral designs on sacrificial towels from an old believers' Prayer house

Автор: Fursova E.F., Vasekha M.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

We reconstruct the semantics of fl oral compositions on commemorative towels, embroidered by women, members of the Old Believers Bespopovtsy (priestless worship community rejecting marriage) in Novosibirsk. The original vine motif, associated with the funerary cult, was transformed by replacing vines with more familiar motifs, such as fl owers, berries, buds, etc. Certain designs resemble those found in late 19th to early 20th century embroidery manuals and on wrappers of cheap soap manufactured by Rallet, Brocard, etc. In most cases, however, there are no exact parallels. Some fl oral compositions are original: for instance, those showing vases with scrolls reminiscent of Jesus Christ’s monogram, and “vases” turned into letters on Our Savior’s icons. The results of the technological and stylistic analyses suggest that most sacrifi cial towels were made in the late 1800s and early 1900s, some in the 1940s and 1950s, and some may have been manufactured in places of the Old Believers’ former residence in northern and central Russia. Designs arranged in friezes or central fi gures, such as crosses, cruciate motifs, “vases”, or “vaults”, allude to the Old Believers’ fundamental values. Ritual towels evidence motifs on commercial embroideries creatively transformed by Old Believers according to their beliefs and traditions.

Floral design, sacrifi cial towels, Russian Old Believers, Priestless Old Belief, Western Siberia

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146034

IDR: 145146034 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.4.125-134

Текст статьи Floral designs on sacrificial towels from an old believers' Prayer house

Studies of modern material culture, including its manifestations in the form of relics, make it possible to expand our understanding of the inner immaterial life of people. Insofar as culture sustains “deeply intimate, innate connection” with spiritual life, i.e. with the whole complex of religious, moral, and aesthetic experiences, it is alive and it has a “soul”. According to O. Spengler, “the soul of culture” is something immaterial, yet captured in specific features of painting, music, architecture, poetry, and scientific reasoning (1993: 262). The attitude to the past, death, the world, and idea of person’s place in the world is manifested in every culture, including its material aspect (Kazakov, 2014: 137). In our opinion, ornamental decoration of towels and other hand-made objects can be considered as self-expression of the “soul” of people, which use fine arts and handiwork to translate symbols and signs understandable to them. Numerous studies on art history and ethnography showed that ornamental motifs combine traditions from various periods. Revealing their content may provide further insight into foundations of

the worldview of their carriers (see, e.g., (Voronov, 1972: 36; Maslova, 1978: 31)).

We believe that even seemingly simple and common ornamental patterns should be analyzed carefully and with regard to their ethnic and cultural context. The principle of variability in folk culture is widely manifested by the publication of ethnographic and other types of atlases. This principle can be successfully used in studying popular designs (Vasiliev, 2017: 124). It makes it possible to analyze various aspects of general and specific features of the traditional ornamental patterns of Russian peasants living in Siberia in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, without focusing only on general aspects (which is common among the supporters of the mythological school) or exclusively on specific local aspects (which is common in local history studies).

The Old Believers had a great influence on the pictorial tradition of Russians, filling it with religious meaning, by manifesting the worldview in which “single ritual meaning was expressed in a variety of forms—from manuscripts to embroidery and prayer”, corresponding to the principles of complementarity and interchangeability of the “subject-oriented, verbal, and actional cultural codes” (Survo, 2014: 194).

During the years of “militant atheism”, the Old Believer community (the Fedoseevtsy denomination) of Novosibirsk was a kind of “integral microcosm” with a secret religious life for its members, an island of “true faith”. Unfortunately, this community was studied by the authors of this article only in the last three years of its existence. A few words should be told about its history. The Old Pomorian denomination was one of the communities of priestless Old Believers, who did not accept marriage. It emerged in the late 17th century, in the Pskov and Novgorod Governorates, and was named “Fedoseevsky” after its founder Feodosy Vasiliev, who had also preached among those Old Believers who fled to Poland (Kharakteristika ucheniya…, 1902: 552; Kozhurin, 2014: 158–163). In the early 20th century, the Old Believers, who were scattered in the villages of the Tomsk Governorate and other settlements of Western Siberia, began to resettle to Novonikolaevsk (Novosibirsk since 1926). In the 1970s–1990s, the leader of the Fedoseevsky community was spiritual father F.V. Gubarev (born 1908), whose family moved to Novosibirsk in the 1930s from the village of Korovka of the Sapozhkovsky District, Ryazan Region, which was a well-known center of hand-made pattern-weaving and embroidery (Pankova, Sakharova, 2011: 67). According to the recollections of Gubarev, the community included people from various parts of Central Russia, including Ryazan, Tula, and Lipetsk regions (for information about the history of the community, see: (Fursova, Golomyanov, Fursova (Vasekha), 2003: 27)). In 1996– 1998, during the time of our communication with these

Old Believers, no more than five-six women over 80 years old participated in the services on Saturdays and Sundays; two of them lived permanently in the prayer house. On feast days and days of commemoration of the dead, up to 15–20 people attended the service, including middle-aged people; as “living in fornication” (i.e., in marriage), they stood behind the group of worshipers (Field Materials of E.F. Fursova (hereafter, FMA), 1996). The commemoration practices included not only a service, with the reading of prayers and recitation the names of the dead (“commemoration of relatives”), but also a joint dinner with the brought food, distribution of cookies and sweets for “commemoration of the soul”, and donation of towels to the prayer house. Towels were donated not only by the community members, but also by the children of the deceased members: they brought towels that were hand-made by their grandmothers and mothers. As Elena Ivanovna Rybina and Klavdiya Andreevna Boldyreva mentioned*, this was customary from time immemorial; towels were always given as alms pleasing to God (it was believed that “in the other world” this could ease the destiny of the deceased’s soul). Until now, at funerals, it is customary for Old Believers to tie towels to crosses and distribute them among those present “for commemoration” (FMA, 1996, observation at the funeral of F.V. Gubarev in 1998). This study was based on the analysis of home-made sacrificial towels (37 items in total) that were kept in the prayer house of the Novosibirsk Fedoseevsky Old Believers (some items had previously been used for elaborating the typology of the Baraba towels (Fursova, 2006)). The collection was formed in the pre- and post-War years, up to the late 1990s (Ibid.). Materials from museum collections were also used as sources (unfortunately, the documentation on these items of handicraft usually indicates only the place of collection and the name of supplier or artisan). Towels from the field collections of the authors, which are kept in the Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of SB RAS, as well as photos of family collections of needlework of the population of Western Siberia, were used for analysis. Field evidence collected in 1980–2010 by the Eastern Slavic Ethnological Expedition of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of SB RAS was an important source of information. This study aims at reconstructing the semantic content of ornamental compositions of commemorative (sacrificial) towels from the collection of the community of Novosibirsk Old Believers.

Floral designs of “vine”

Most traditional Russian patterns are based on relatively few images and compositions. Russian scholars have usually focused on geometric ornamentation, as well as zoo-, anthropo-, and ornithomorphic motifs (Maslova, 1978; Rusakova, 1985; Fursova, 2005, 2006; Gribanova, 2013; Survo, 2014; and others). “Grass” designs have been analyzed less frequently, although these often occur in the Old Russian applied art and architecture of the 10th–13th centuries and in the initials of the manuscripts of the 12th–14th centuries (Maslova, 1978: 95). Floral patterns appear on over 90 % of sacrificial towels of the Old Believer community of Novosibirsk. A similar situation is observed in the evidence from large museum collections of the Altai (Gribanova, 2013: 167) and the Russian North (Survo, 2014: 71).

The vine motif is reasonably used in decorating the towels intended for commemorating the souls of deceased Christians. The image of grapes and vine in the Bible symbolizes spiritual fruit blessed by God (for example, Lk. 22:18) and the Garden of Eden, and is associated with the funerary cult. The first symbolic meaning of vine was related to Christ and his disciples, and second meaning was associated with the Christian Church (Uvarov, 1908: 173). Many examples of interpretation of this symbol appear in the Bible. For instance, the book of the Prophet Isaiah says: “Now will I sing to my wellbeloved a song of my beloved touching his vineyard. My wellbeloved hath a vineyard in a very fruitful hill. And he fenced it, and gathered out the stones thereof, and planted it with the choicest vine” (Is. 5:1–2) and “As the new wine is found in the cluster, and one saith, destroy it not; for a blessing is in it” (Is. 65:8).

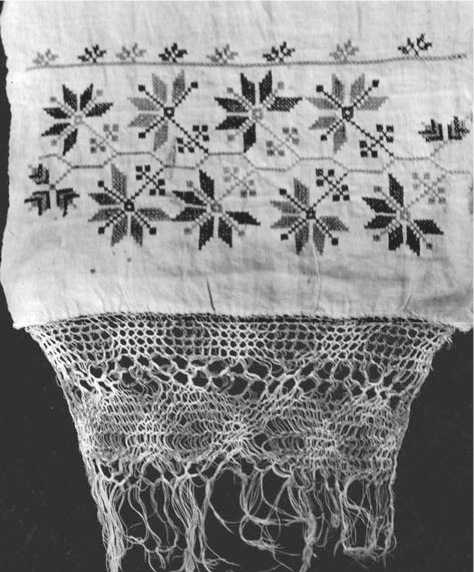

Bunches of grapes, which sometimes resemble berries, in the patterns on the Old Believers’ towels under consideration alternate with leaves or flowers in the form of rosettes, etc. (Fig. 1). In terms of color palette, they correspond to the general Russian tradition based on the combination of white linen, and red and black threads in the pattern. Polychrome variants also occur. Embroidery on sacrificial towels was done mainly with cross-stitching. Notably, among other ethnic and cultural groups of Russian peasants in Siberia, this motif was rendered using customary techniques. For example, the Chaldon old residents performed it with a traditional buttonhole stitch (tambour stitch) (Fig. 2). The Chaldon embroidery looks like a two-colored (red and white) graphic pattern, with intricately twisting lines and without spaces within. Bunches of grapes and leaves in the frieze pattern are shown in a stylized manner; vines are rendered by small loops. In the central part of the embroidery, in the crown of winding lines, one can see a flattened anthropomorphic figure (Fig. 3). Syncretism (a combination of phyto- and anthropomorphic images)

is generally a phenomenon typical of archaic imagery (Maslova, 1978: 94; Rusakova, 1985: 133).

The Russian archaeologist and corresponding member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences A.S. Uvarov noted that Christians used the images of pagan monuments that were “consecrated” through the interpretations of Church Fathers of the first two or three centuries AD (1908: 103). When choosing symbolic images, Christians relied on the works of Clement of Alexandria and other writers of his time. The acceptable symbols included the symbols of “dove”, “fish”, “lyre”, and “anchor”. Over time, symbols borrowed from Holy Scripture and works of other Church Fathers were added to them (Ibid.: 104). The antiquity of the image of a vine is confirmed by its occurrence in ornamentation of clothing of votive statues from the Hellenized East of the 2nd century AD (Parthian art, Ashur and Hatra) (Schlumberger, 1985: 124). Village craftswomen could see this image in the decoration of iconostases, icons, and books. They probably knew about grapes as a real plant from the stories of pilgrims returning from Palestine (Belyaev, Chekhanovets, 2020: 98). In the process of creative assimilation, the craftswomen filled the image of a vine with the relevant content, and embodied it in new forms: for example, replacing grapes with more familiar items from surrounding nature (Fig. 4, 5). Certain designs show similarities with those found in late 19th to early 20th century embroidery manuals and on wrappers for cheap soap manufactured by Rallet and Brocard; these are known in the literature as “Brokarovsky” (Maslova, 1978: 54). However, most of the ornamental patterns embroidered by rural craftswomen do not find direct parallels in printed examples. This indicates that the pictorial ornamental language introduced into the peasant culture from without corresponded to the traditional imagery and to the entire set of basic values of the Old Believers. Thus, the predominance in the collection of sacrificial towels with a design in the form of a curling shoot with flowers as a typical and widespread motif is not accidental (Zhilina, 2018: 33). “Flower vine” often occurs in the ornamentation of old icons, books, and more mundane things, such as men’s traditional kosovorotka shirts for festivities and weddings (Charyshsky District, Altai Territory) (FMA, 1988).

Here is the description of some towels with such a design from the Novosibirsk prayer house (25 spec.). The embroidery often depicts two vines: the upper vine is shown in a decorative and geometric style, in the form of alternating rosette flowers and twigs; the lower vine appears with realistically rendered leaves and flowers (see Fig. 4). In the design of one towel, a wavy line, uniting flowers and leaves, is rhythmically interrupted; nevertheless, it is perceived as a grapevine, although it is not entwined around a tree. “Flower vines” were

Fig. 1. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Fig. 2. Ends of a towel made in the tambour (“loop”) technique, late 19th century, Novosibirsk Region. Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of the IAET SB RAS.

Fig. 3. Ends of a towel made in the tambour (“loop”) technique, late 19th century, Novosibirsk Region. Museum of History and Culture of the Peoples of Siberia and the Far East of the IAET SB RAS.

Fig. 4. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Fig. 5. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique. The Charysh Museum of Local History, the Altai Territory. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

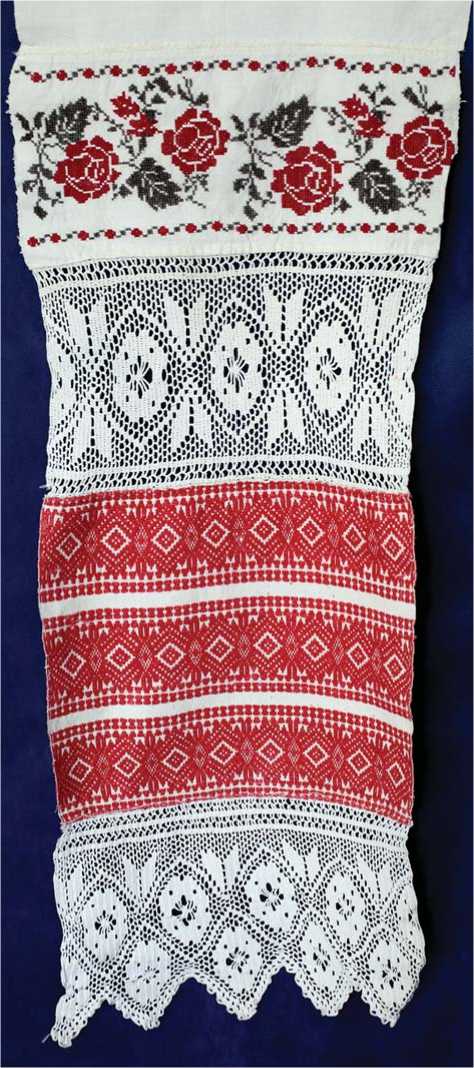

often enriched with buds, flowers, and leaves of various sizes, and the ornament looked rich and “branchy”. The collection under study contains a towel with a clearly legible vine of the “Brokarovsky” type; it has acorns, which alternate with leaves, and entwines around a stem (tree trunk?) (Fig. 6). The design on another towel combines representations of vine and two large squares below, with the inscribed eight-petal rosettes and crosses (Fig. 7). Taking into account Siberian evidence, geometric zigzags with surrounding flowers or bunches of grapes can be attributed to the flower vine design. Wavy vine in this case is replaced by a broken line (Fig. 8). Compositions made with cross-stitching (on three specimens) in the 1940s–1950s include sophisticated asymmetrical realistic images of specific flowers (red lilies, roses, etc.) and can be attributed to the “Brokarovsky” type.

The designs described above have much in common with patterns on towels from the rural population of the Russian North. However, the motif of a flower vine among the northerners was usually combined with geometric ornaments made via loom weaving technique (FMA, 2010; Fig. 9). Such an ornament became widespread in Eastern Europe; it appears on hand-made items of the 19th to early 20th centuries created by Polish, Romanian, and other rural craftswomen.

Floral designs with “vases”/“houses”

According to Uvarov, the image of a chalice was closely related to the image of a grapevine (1908: 104). Floral

Fig. 6. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

patterns combined with a chalice/vase (vases) occur on about 10 % of compositions on the towels from the Old Believers’ prayer house. They were made using counted techniques: cross-stitch, satin-stitch, and white thread embroidery (on sparse fabric).

Vases in embroidery are not always shown realistically. For example, on two towels from the collection under consideration, the vase is represented as curled letter “X” (Greek “chi”) (Fig. 10). In this case, the inflorescence between the scrolls can be associated with letter “I” (“iota”) of the Greek alphabet. Such monograms with the crossed interposition of initial letters of the name of Jesus Christ have been found on gravestones from the first centuries of Christianity

Fig. 7. Ends of a towel embroidered using the counted satinstitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Fig. 8. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique. The Chistoozerka Museum of Local History, Novosibirsk Region. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

Fig. 9. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, the town of Totma, Vologda Region. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

and on the vaults of the Archbishop’s Chapel of the 5th century in Ravenna (Kak vybrat…, 2003: 23). On one towel, vase is depicted with scrolls facing inward like the Greek letter “Ω” (“omega”) (Fig. 11). Icon painters depicted the letters of the Greek alphabet on the icons of Christ. For example, on the icons of the Savior Not Made-by-Hands (the Holy Mandylion), one can see letter “Ѿ” (Russkiye ikony, 2004: 65, 67).

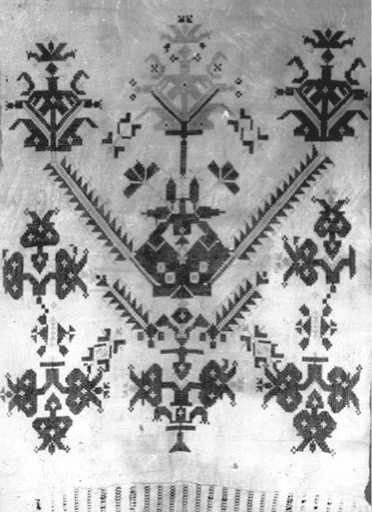

In embroidery, the image of a “vase” was rendered as small house, from which a large plant stretched upward; the branches at the middle level were directed upward and downward (emanating from the corners of the square in the center of the plant), and at the top level they were directed only upward. It is clear that the lower and upper branches are separated horizontally (Fig. 12). The top of the plant is a trefoil framed by small V-shaped figures (birds?). Similar embroidery on towels has been found occasionally in different regions of the Novosibirsk region of the Ob, Vasyugan Plain, and Northern Altai. For example, a composition of floral patterns, vases, and houses with “sprouted” roofs occurs on towels from the collection of the Ordynskoye Museum of Local History, and on embroideries found during the expedition to the village of Yarki in the Cherepanovsky District, Novosibirsk Region (Fig. 13, 14) (FMA, 1993). A towel with an ornamental pattern of a spreading tree with raised branches and numerous inclusions of phyto-anthropomorphic figures, crosses, house-vases from Yarki shows similarities with the Ukrainian embroidered shirts from Podolia (Dintses, 1941: 31). A towel with figures that can be regarded as a typologically early prototype of the image of plant with vase has survived among the Russian Old Believers of the Vasyugan Plain—the descendants of migrants from Glubokovsky Uyezd of the Vilna Governorate of the early 20th century (Fig. 15). The ornament was made using the counted technique; therefore, the vases, from which the trees with upturned branches grow, look stylized. The phytomorphic images end with diamond-shaped figures, which are a continuation of three crosses emanating from the plant’s trunk. Large and spreading trees are embroidered on the sides of a less spreading tree or a bush in the center. Tripartite compositions with plants of various types demonstrate a connection between green, fruit-bearing trees and dry, fruitless trees; similar images occur on Early Christian monuments (Uvarov, 1908: 193). Some scholars suggest that these compositions with floral and anthropomorphic symbols were intended to indicate the purpose of the embroidered items and to emphasize their connection with female space, with periods of girls’ full age, wedding, and youth (Bernshtam, 1992: 237; Survo, 2014: 73). Such an explanation appears to be more suitable for the semantic content of compositions on the needlework produced by the followers of the official

Fig. 10. Ends of a towel embroidered using the counted satinstitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Fig. 11. Ends of a towel embroidered using the counted satinstitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Church or those Old Believers who accepted marriage. There is an opinion that the embroideries of the Great Mother ruling over all the worlds were executed in a typologically similar iconography (Rusakova, 1985: 133–134). It is impossible to decipher such compositions convincingly, and it is unlikely that this

Fig. 13. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique. The Ordynskoye Museum of Local History, Novosibirsk Region. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

Fig. 12. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, from the collection of the prayer house of the Old Believers in Novosibirsk. Photo by S.I. Zelensky.

Fig. 14. Ends of a towel embroidered using the cross-stitch technique, the village of Yarki, Cherepanovsky District, Novosibirsk Region. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

III Hl Hi

Fig. 15. Ends of a towel embroidered using the counted thread technique, the village of Bergul, Severnyi District, Novosibirsk Region. Photo by E.F. Fursova.

will become possible in the future. There will be no carriers of this artistic tradition, which has been long gone from the lives of many generations of Russians, and Slavic peoples in general.

The symbolism of such images must be viewed using extensive material evidence, especially because the parallels can be found not so much in the common Russian, but in the Indo-European repertoire. Christians also borrowed the symbol of the flow of life (house) from the ancients; in particular, from the Greeks and Romans (Uvarov, 1908: 170). Early Christians interpreted it as a vault or a church. It is logical to interpret houses as vaults in the ornamental patterns with houses from which mythical plants grow. It is possible that in the old days the embroiderers tried to convey the meaning of “everlasting life”, eternity of being, and connection between the past and present in their works. In the designs of towels of the Ukrainian settlers in Siberia (the “Krolevets” settlers from the town of Krolevets, Sumy Region), houses with tops in the form of crosses, usually separated by bands from floral and other patterns, symbolize religious buildings (churches). The outlines of houses or vases cannot be discerned in the ornately curved lines of the Chaldon hand-made items.

Conclusions

Floral motifs typical of the Russian tradition of needlework as a whole, and specific to the group of Fedoseevsky Old Believers under study, have been identified in the collection of sacrificial (commemorative) towels of the Old Believers’ prayer house in Novosibirsk. This collection was based on the desire of the community members to do a godly deed—to donate a cherished thing left from the ancestors on the female side (grandmother, mother, mother-in-law) to the prayer house. The Godpleasing nature of ornamented towels as a commemorative sacrifice is reflected in funeral and commemorative customs that have survived among the Orthodox population, including the Old Believer groups of Siberia: towels were used for tying stretcher poles, supporting icons while carrying out the deceased; towels were given to grave-diggers, were tied to the cross, etc. (Fursova, 2014: 287–288).

An important result of working with the materials (the collection of towels from the Old Believers’ prayer house) is the conclusion about the transformation of the Old Christian image of a “vine”: while rendering it in their embroidery, Orthodox craftswomen replaced grapes with flowers, leaves, buds, etc., which were more familiar to them. Replacement of a grapevine with flower, oak, or berry vines has also been observed in the ornamentation of towels of the Orthodox population in the countries where Orthodoxy is the dominant religion (e.g., Romania) or where the Russian Old Believers live (e.g., Poland). Original compositions with a “vase” in the form of monograms combining the initial letters of the name of Jesus Christ have been identified. The collection contains a towel with the image of a “house” from which a large plant is directed upwards. This motif may represent the so-called World Tree traditionally known from the art of the peoples of Eastern Europe (Maslova, 1978: 95), but without figures of animals, birds, or riders on the sides, and without the anthropomorphic features typical of this motif.

Being embedded in the hierarchy of ethnic and cultural identity, and more precisely of its form as denominational identity, floral patterns in “their true essence” contributed to the consolidation of the Old Believers into a single community. Only the members of the community passed towels to each other; selection of ornamental motifs probably occurred at the same level.

Variants of the motifs in the embroidery on the towels from the collection of the Old Believers’ prayer house in Novosibirsk could result from adapting the well-known Christian Byzantine images to expressing the “festive feeling of peace”, which appeared in Russia at the turn of the first and second millennia. According to M.A. Nekrasova, “with the adoption of the Orthodox faith, Christian elements merged into the traditional popular system, finding a basis in the community of more ancient traditions”, which testifies to creative capacity of Russian peasant women and their “spiritual giftedness” (2006: 13).

The pattern with grape clusters and leaves, both realistic and stylized, appears in the material culture of almost all Eastern Slavic groups of Siberia—Russian Old Believers, Chaldons, Ukrainians, etc. Ornamentation in the form of a spreading tree with branches raised up and numerous inclusions of phyto-anthropomorphic figures, crosses, house-vases occurs much less frequently. In our opinion, it shows parallels with Western Russian traditions.

Analysis of the manufacturing technique and the style of patterns suggests that most of the sacrificial towels from the collection of the Novosibirsk prayer house were made in the late 19th to early 20th centuries; a smaller part was made in the 1940s–1950s, and some were probably brought from other places of the initial location of the Old Believers (Russian North, Central Russia).

Acknowledgement