From Chauvet to Lascaux: 15,000 years of cave art

Автор: Geneste J.M.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Art. The stone age and the metal ages

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145323

IDR: 145145323 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.3.029-040

Текст статьи From Chauvet to Lascaux: 15,000 years of cave art

In Western Europe and especially in the Atlantic zone, the western part of the Mediterranean, explosion of rock art is associated with Homo sapiens, carriers of a specific hunter-gatherer culture that developed over this territory during the glacial period*. The first manifestations of visual art are noted in the Aurignacian, the culture of the Upper Paleolithic, which was very long-lasting and widespread. This phenomenon covers a period of 36–13 ka BP.

The most expressive monuments of cave art, such as Altamira (Breuil, 1952), Trois-Frères (Breuil, 1952; Bégouën et al., 2009), Niaux (Breuil, 1952), Lascaux cosmological model, a different perception of the world, a different ontological concept (Cauvin, 2000), and different ways of transferring knowledge. This is a completely different world, where agriculture will later occur (see, e.g., (Bar-Yosef, 1997; Davidson, 2012)).

(Aujoulat, 2004; Geneste, 2012, 2015b), Cosquer (Clottes et al., 1992), Chauvet (Breuil, 1952; La Grotte…, 2001, Recherches…, 2005; Geneste, 2015a) and Cussac (Aujoulat et al., 2002), shed light on the sociocultural behavior of, and the areas of interest to, the anatomically modern humans. When visiting these monuments, it becomes obvious what an exceptional value the images rendered in the caves had in the ideology of their creators. These were manifestations of the first forms of mythology and religion as the concepts of understanding the world, represented in the form of graphics, drawings, and portable art.

In this paper, we provide an analysis of changes in symbolic language, in the ways animals are rendered, and in the layout of artistic space over 15,000 years. These are well traced primarily in two caves, where primitive art has survived in excellent condition. The Chauvet (36 ka BP) and Lascaux (21 ka BP) are amazing archaeological sites, which have no analogs. Like all the great masterpieces engendered by human consciousness, whether monumental statues or the most significant sacral sites, these are (in the perception of the early last century, as proposed by H. Breuil and R. Lantier (Breuil, Lantier, 1951; Breuil, 1952)) simultaneously unique works of art, and sanctuaries, inextricably connected with the environment. They depict deep cultural features or, in other words, fossil traces of human thought that are either arranged sequentially, or scattered in an unimaginably vast space of time. They tell us about commonalities and differences, about the continuation of traditions and novelties.

Art in the depths of caves

From the beginning of its spread over Western Europe at the early stages of the Aurignacian culture (more than 40 ka BP), primitive art looks not only mature, but full of dynamism and amazing creative potential. Its expressiveness is mainly the result of the imagination of people who were the creators of the first art*. In the darkness and silence, in the depths of the caves, this responded in the imagination, thereby giving birth to a myth. In the light of the day, a completely different art surrounded the everyday life of a human—the art of daily

*Here, for simplicity of understanding, the term art embraces a variety of different categories connected with pictorial activities, from the decor of everyday objects to a purposefully rendered shape. This designation cannot be associated with anything besides aesthetic value, mythological and, in a broad sense, spiritual fullness; but at the same time, these categories have nothing to do with the modern understanding of this term (see, e.g., (Davidson, 1997, 2012; Conkey, 1997)).

life, the present. The hidden cave-space, apparently, functioned quite differently: these were sacred places, where the spirits of humans, animals, and nature were somehow co-present (Geneste, 2012, 2015a).

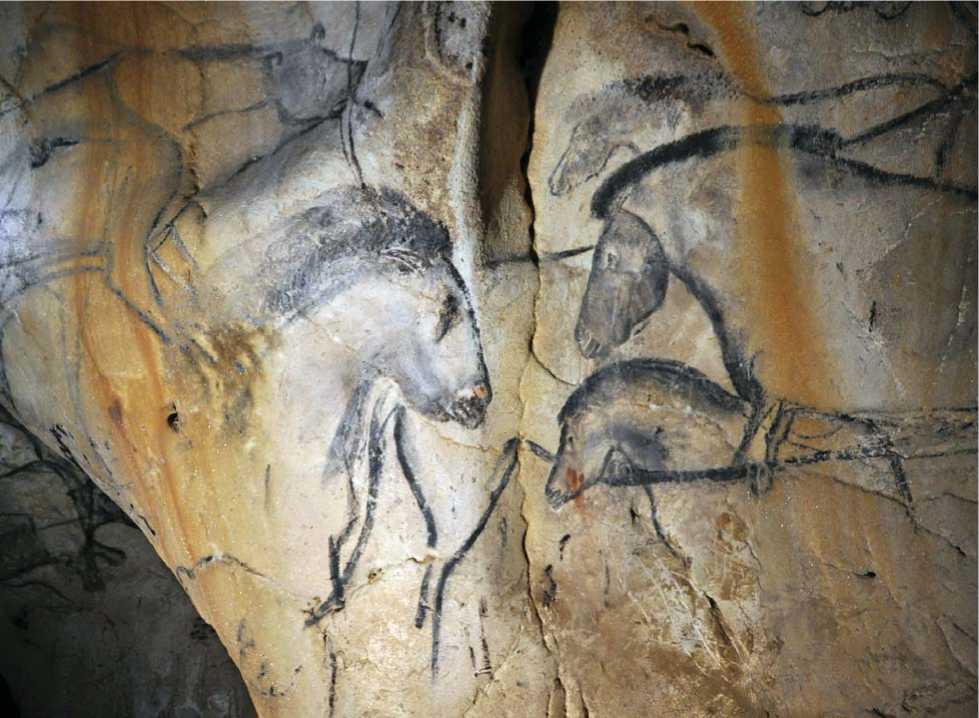

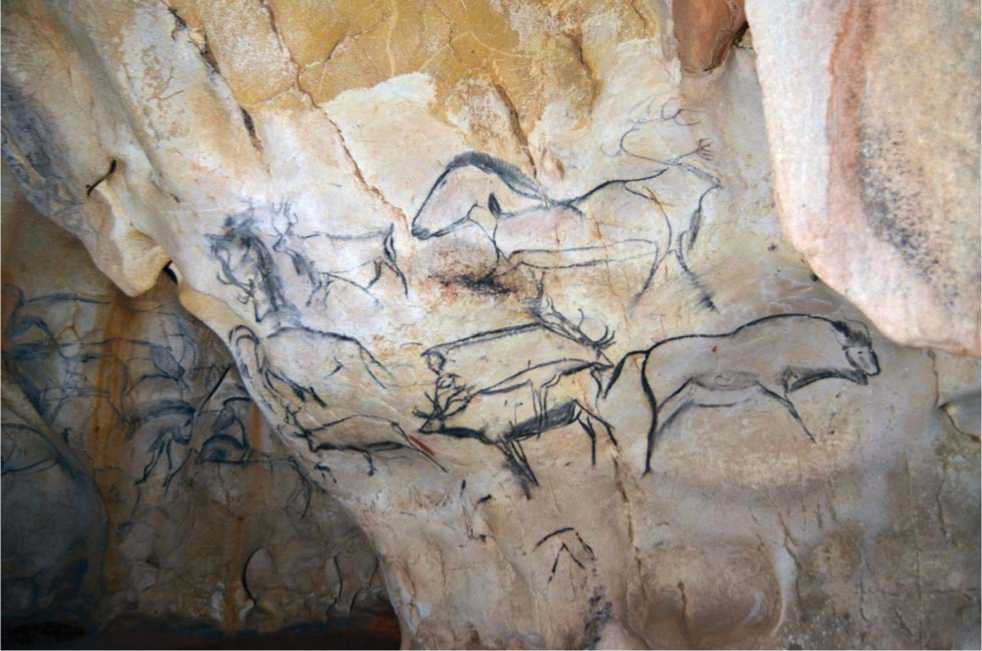

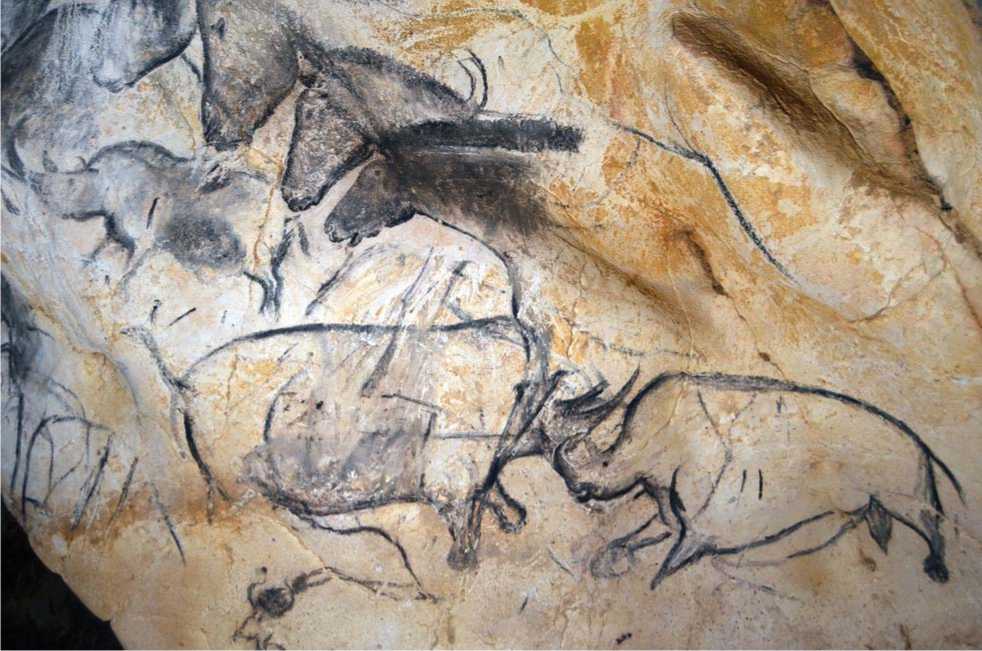

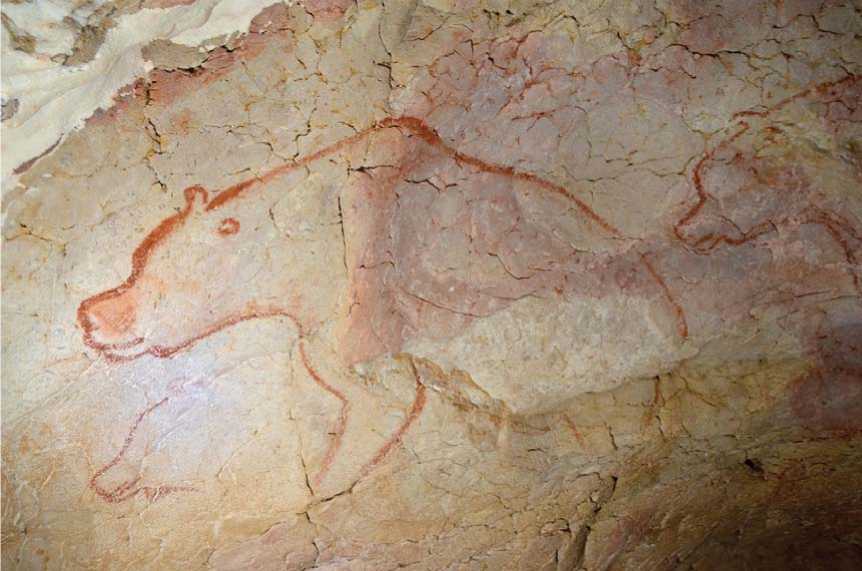

By the example of the Chauvet cave*, with its dynamic and expressive images of animals (Fig. 1), located separately from each other or showed in complex compositions, we can see a permanent presence of imagination. Here, images of aggressive and powerful animals such as mammoth, lion, leopard, rhinoceros, giant deer, and bear prevail. Bison, aurochs, horses, deer, and goats are widely represented, too.

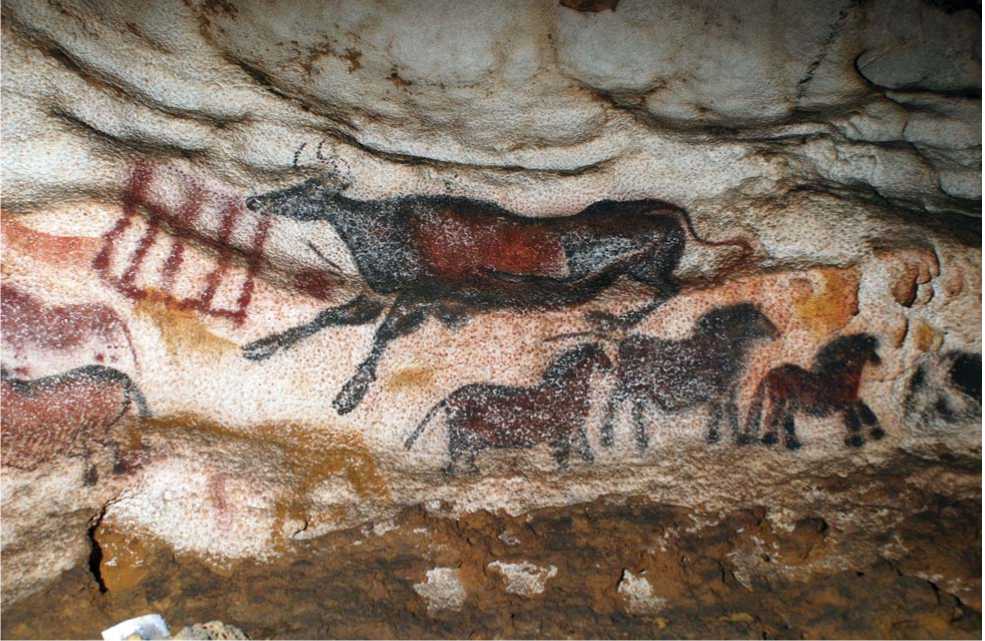

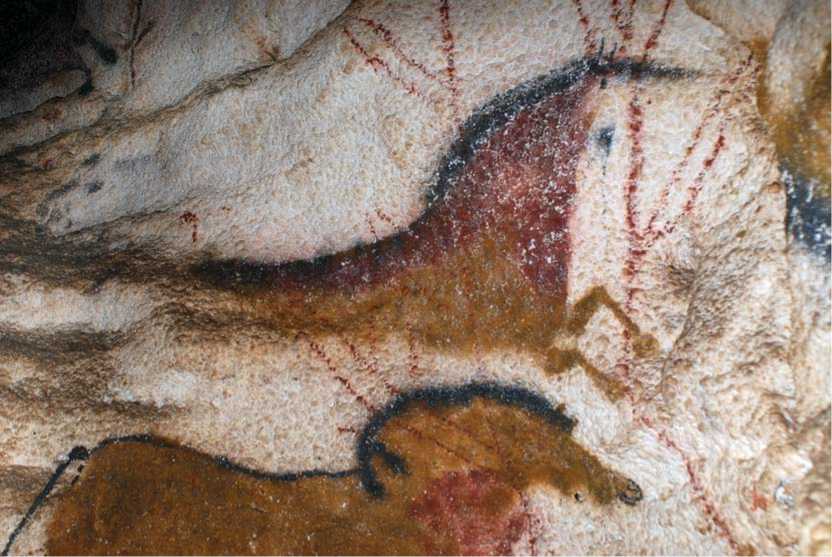

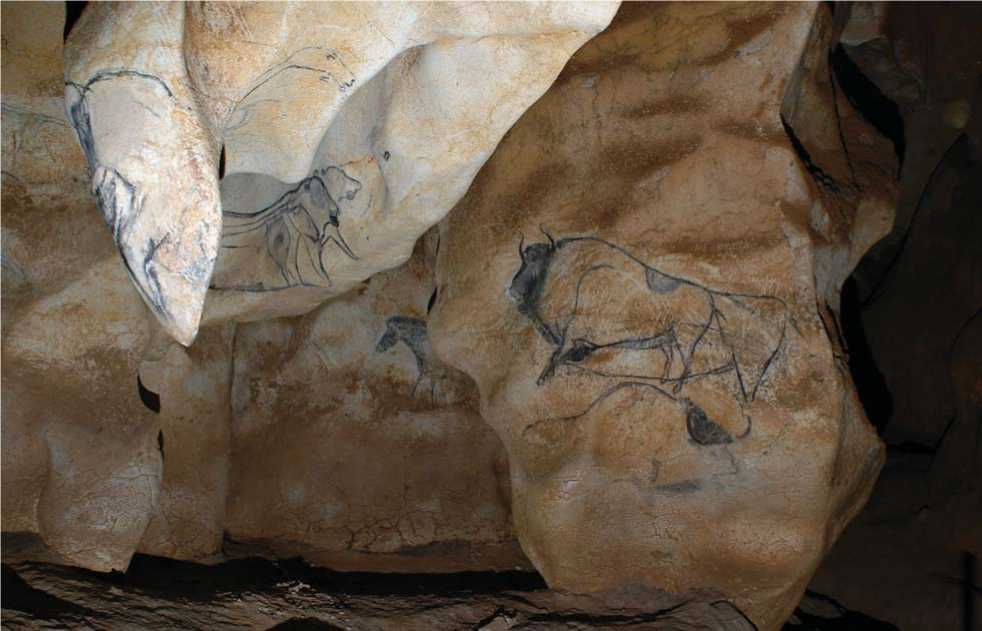

In Chauvet, as in Lascaux, only the representatives of individual species were depicted, except for fantastic zoomorphic images combining features of various animals. This was a sample made by a human from all the surrounding animal kingdom. Animalistic subjects, not very diverse over about 25 thousand years, were used as abstract symbols designating living beings (humans and animals) in the darkness of caves. During the Upper Paleolithic, a set of depicted animals evolved in accordance with cultural and climatic changes. In Lascaux, images of bison, aurochs, and horses already predominate (Fig. 2). At the same time, images of deer, bear, lion, and rhinoceros still occur, but already in a different status.

Other subjects in the cave art

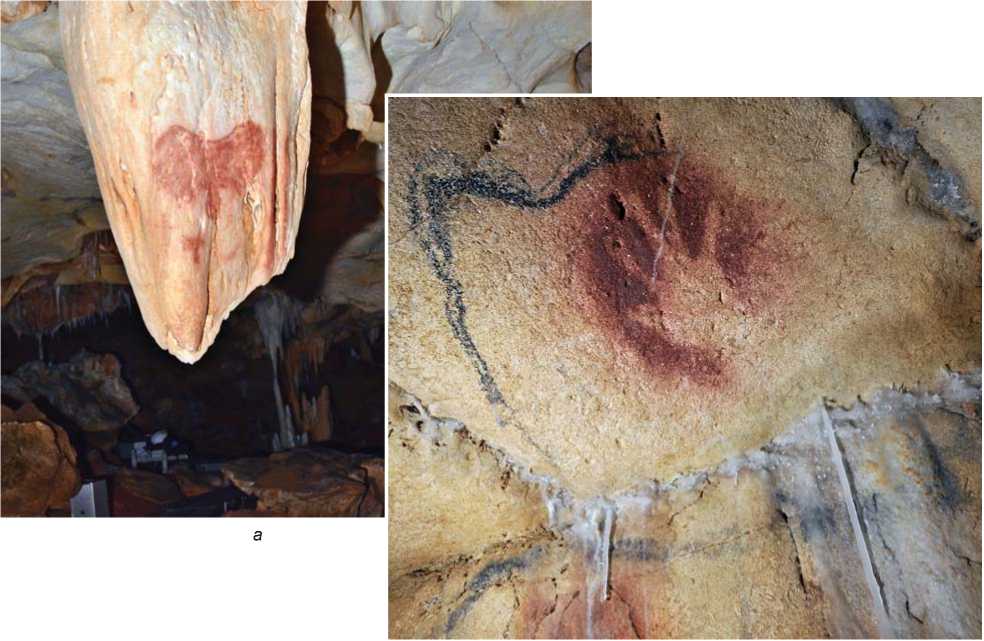

In Lascaux, in addition to the animal images, there are quite a lot of abstract symbols (Fig. 3). These are signs of various geometric forms, sometimes figurative, but their meaning is unclear to us. Some symbols found in Chauvet Cave are typical of the Gorges de l’Ardèche: a sign in the shape of W and the so-called bilobed symbols (resembling a butterfly) made with a red pigment and divided by a line in the middle (Fig. 4). In Lascaux, as in most of the caves, there are no floral motifs. An exception is one image (executed using a red pigment) overlapping the figures of horses in the depth of the Passageway (Fig. 5).

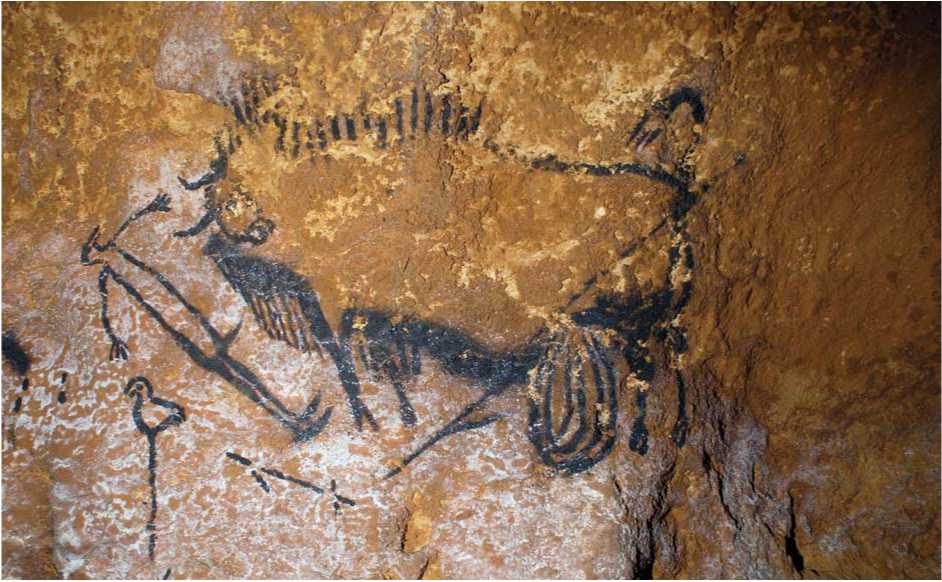

Anthropomorphic images are often partial, and unrealistic, even “caricatured”, and are always extremely rare. They are usually located far from the entrance, in the depths of the most distant gallery, where drawings are densely concentrated. In Lascaux, the only known depiction of a human is hidden at the bottom of a hard-to-reach well deepening. The image is rendered schematically, and its anthropomorphic features are combined with ornithomorphic ones (bird’s head)

Fig. 1. Alcove of Lions in the Hillaire Chamber of Chauvet Cave.

(Fig. 6). In contrast, the first image that opens the Hall of the Bulls is a figure of a mysterious and fantastic animal, a unicorn. Its body looks as if it consists of parts of animals of various species.

In Chauvet, anthropomorphic images are always placed in the structure of compositions. These are partial representations, and also symbolic images in the form of triangular female signs, represented in the Megaloceros Gallery . One anthropomorphic image is imprinted in the distant hall of the cave: a lower part of the female body is depicted on the hanging narrow conical salient. The drawing is compositionally connected with images of a bison, a lion, and a lioness, located in the same space (Fig. 7). It is comparable to others, painted in a similar manner. As far as the zoo-anthropomorphic images are concerned, there is only one example of such a fantastic creature in the Aurignacian period: representation of a human with a lion’s head in Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave, in the Swabian Alps. In addition, there is one example known from the Magdalenian period: a “sorcerer” in Trois-Frères Cave, in the Pyrenees (Breuil, 1952). Thus, this pictorial tradition has existed for many millennia.

Arrangement of animal images in a cave

Locations of drawings in a cave are not accidental. Ancient “artists” intentionally chose special sites, and sometimes they made special preparations at these sites. The space with drawings constituted a harmonious meaningful ensemble. A. Leroi-Gourhan (1965) was the first to pay attention to the special arrangement of space in cave art, in the early 1960s.

In terms of delicacy of performance and compositional complexity, the ensembles of Chauvet Cave have no analogs, because here we see full-fledged compositions, in every sense of the word. Some of them contain several dozens of animal representations (Fig. 8). The soft, pliable surface-texture of many cave-walls allowed artisans to return to these compositions, permanently supplementing them. It is well seen here how the surface changed at various stages of creation of drawing series, and what successive changes were made before the completion of this complex artistic ensemble (Fig. 9).

In Lascaux, the sequence in which the images were drawn at various periods of time can be traced quite clearly,

Fig. 2. Images of ungulates (horses, aurochs, bison) in Lascaux Cave.

Fig. 3. A sign in the form of a lattice. Lascaux.

а

5v

1 .

b

Fig. 4. A bilobed symbol divided by a line in the middle ( a ), and a handprint ( b ). Chauvet.

Fig. 5. Floral motifs. Lascaux.

Fig. 6. Anthropomorphic image with ornithomorphic features. Lascaux.

Fig. 7. Representation of a lower part of the female body, compositionally connected with the figures of bison, lion, and lioness, in the distant hall of Chauvet Cave.

Fig. 8 . Complex compositions consisting of several images of animals, in Chauvet Cave.

Fig. 9. Panel-pictures made using an engraving technique on the soft surface of the wall of Chauvet Cave.

Fig. 10. Palimpsests in Lascaux Cave: overlapping the small figures of bulls and horses with a large painting of a bovid.

because it is associated with changes of subject. There is an imposition of images of large black bulls on the figures of horses and smaller red bulls, observed repeatedly in several places (Fig. 10). These palimpsests recorded in a number of galleries may be interpreted in various ways. The cases where the top drawings completely cover the lower ones may be explained by the fact that the drawing of images was connected with self-identification of various population groups. Newcomers attempted to hide the drawings associated with other communities and, as a consequence, to mark the given territory as their own. In the cases where the fragments of the lower images seem to peep out from under the upper ones (which could have been intentional), this might indicate the evolution of views and thoughts, but at the same time testify to the continuity of the development of a certain intent and respect towards the works of predecessors. This interpretation illustrates the concept of cultural differences. However, it should be borne in mind that the creators of these palimpsests were apparently separated by a fairly long period of time, which could have included alternation of generations, centuries, and even millennia.

Large spaces and secluded places

Recent observations in Chauvet Cave offer new prospects for possible interpretations. Some characters, such as bears, are located in hard-to-reach places (Fig. 11). One can find them only if one is very good at navigating in a pile of large, chaotically arranged stones, and only by oneself is it possible to penetrate this narrow space.

In the Paleolithic, people deliberately created monumental art ensembles intended for the community as a whole (for example, the surface with representations of horses and the distant hall of Chauvet or the Hall of the Bulls and the Passageway of Lascaux). However, at the same time, there were hidden, secret works of art, placed in narrow, remote places, where only the sight of a knowledgeable person could have recognized them. Such are, for example, the depictions located in the Apse , the Shaft , and the Chamber of Felines of Lascaux Cave. Within the same period, the cave could have had various functions and visited with various purposes. Chauvet is an example of amazing cave art and the greatest sanctuary. Here we can see various uses of one monument: on the one hand, large spaces with huge panel pictures; on the other, secluded places with separate images, not intended for the general public. However, this phenomenon could have also been associated with visiting the cave by various groups of people who expressed themselves in different ways.

Creation of life on the virgin walls of a cave

Within Western Europe, caves, being the abodes of dangerous animals, represented a completely different

Fig. 11. Image of a bear in a narrow passage. Chauvet Cave, Brunel Chamber.

world from the one humans created around them in open spaces. Take, for example, the light that humans had to “tame”, in order to control the level of illumination using torches and hearths. The latter are quite numerous in Chauvet: at almost every site of the cave, remains of charcoal and traces of fireplaces were discovered. In Lascaux, the use of oil lamps was very probable.

At the times when hunter-gatherer-fishers came to symbolic thinking and had only begun to express their ideas graphically, they had at their disposal the untouched, virgin cave walls. And they chose the most suitable ones for creating meaningful performances rendered through animal images and abstract symbols. At the same time, even for the most masterfully reproduced paintings they used the simplest means. Creation of a dynamic image of an animal meant the creation of life. This principle made the art even more realistic, since the images of animals became the main characters and some kind of transport in a mythological narrative. The recurrent compositions on the walls of caves and similar subjects in portable art, represented at various sites and sometimes even in various regions, indicate the commonality of ideas connected with them, and consequently, the common oral traditions. This suggests the interaction between the population groups, which apparently used the same myth (Godelier, 2007).

Meanings in the cave art of Chauvet and Lascaux

At present, in social anthropology, the main types of worldview have been formulated, which allows us to attribute, at a conceptual level, the perception of the world by Paleolithic hunter-gatherers to one of these types (Ibid.). The world-perception of these people was not divided into categories of “living” and “lifeless”, “human” and “animal” (Descola, 2006; La fabrique…, 2010). In the cave art both in Lascaux and Chauvet, probably for similar reasons, a deep empathy is observed: an unquestioned idea on the affinity between humans and the large mammals, both herbivores and carnivores, whose images prevailed.

The skill of the first “artists” was primarily due to the fact that they were hunters responsible for survival of their relatives. They hunted at the risk of their lives, meeting face to face the animal world, which they knew very intimately, up to the smallest habits; and they clearly realized that the animal that is to become food instantly turns into a spiritual ally, a mediator in the spiritual practice, embodied in the image. In the Paleolithic, animals became food for a human himself and for his imagination. Thus, the predominance of animalistic subjects in the cave art reflects the spiritual affinity existing between animals and humans.

Conclusions

Cave art had existed in Europe in Paleolithic over several dozens of millennia. Animals were the first thing that humans began to depict, to think about, and to recall in their imagination. This close relationship or spiritual symbiosis between animal and human is basic and lifegiving. The masterpieces of Chauvet and Lascaux are separated from each other by 15,000 years, and reflect the difference in the content of the thought-processes of anatomically modern humans. These amazing paintings tell us about two peculiar cultures of the world that we can only slightly touch, the world of traditions, which knew both long succession and stability, and also turning points, novelties, and oblivion.

Acknowledgements

This study was performed as part of the project of multidisciplinary study of prehistoric art of Eurasia (Novosibirsk State University – University of Bordeaux), under the Program of Competitive Growth of the Novosibirsk State University in the global market of scientific and educational services.