From “Pure” Roman to “Pure” Byzantine, Through Spolia: The Architectural Details in Afridar (Ashkelon)

Автор: Svetlana Tarkhanova

Журнал: Schole. Философское антиковедение и классическая традиция @classics-nsu-schole

Рубрика: Статьи

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.20, 2026 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Modern Ashkelon, founded on the extensive remains of ancient Ascalon, is rich in architectural details; most are focused in the National Park near the Severan Basilica. However, many other artifacts are scattered throughout the current city. In the northern suburb known as Afridar, several collections of architectural elements are displayed at three open-air exhibitions—the “Court of Sarcophagi” and two locations on the shore. The origins of most of these items cannot be determined at this time, although some appear in documentation from the British Mandate period (1930s). This article highlights architectural details from Afridar, mainly from the “Court of Sarcophagi” exhibition, as well as from other sites in Ashkelon. Besides three items with Greek inscriptions, the rest have not been published until now. The author groups them into four categories based on style and date: 1. The “Purely” Roman details; 2. The Roman-Period Spolia Group; 3. The Byzantine-Period Spolia Group; 4. The “Purely” Byzantine-Period Group. All likely belonged to colonnaded structures of Roman and Byzantine Ascalon, such as streets, basilicas, and churches. Some elements are unique in style and lack parallels in local Roman-Byzantine art, and therefore deserve special attention and analysis despite their unclear original context.

Ascalon-Afridar, polis, Roman basilica, Byzantine church, architectural details, capitals, columns, bases, pedestals, fluted cornice

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147252940

IDR: 147252940 | DOI: 10.25205/1995-4328-2026-20-1-113-155

Текст научной статьи From “Pure” Roman to “Pure” Byzantine, Through Spolia: The Architectural Details in Afridar (Ashkelon)

This article highlights some architectural details featured at the exhibition “Advance Ascalon, Advance Rome” in the so-called “Courtyard of Sarcophagi” in Af-ridar, modern-day northern Ashkelon, recently renovated by the Israel Antiquities Authority. All the architectural finds on display were uncovered during the late British Mandate period in the 1930s, on the eve of archaeological research in ancient Ashkelon.

Ashkelon (ancient Ascalon1) has been known since ancient times, already mentioned in the Bible2 as one of the five Philistine cities (12th–end of 7th centuries BCE). The Greek historian, Herodotus (circa 484–425 BCE), mentioned the famous temple of Aphrodite in the city.3 Ashkelon’s strategic location along the ancient Via Maris and its role as a key port city contributed to its prosperity throughout the 1st millennium BCE.

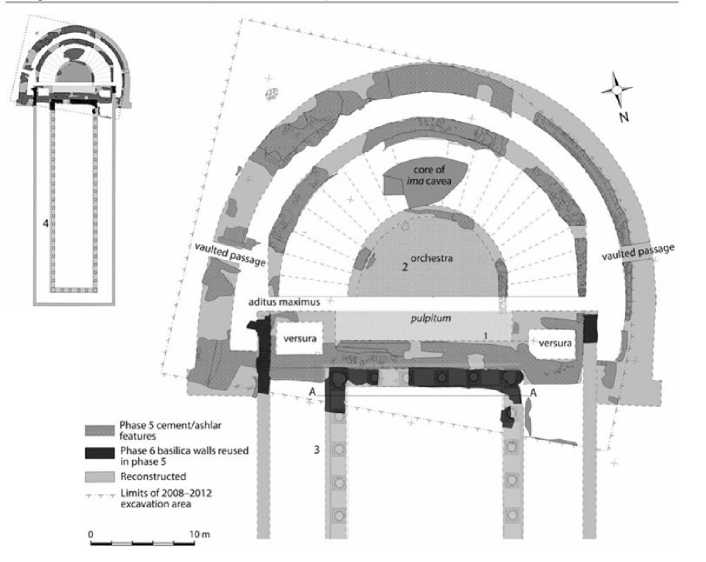

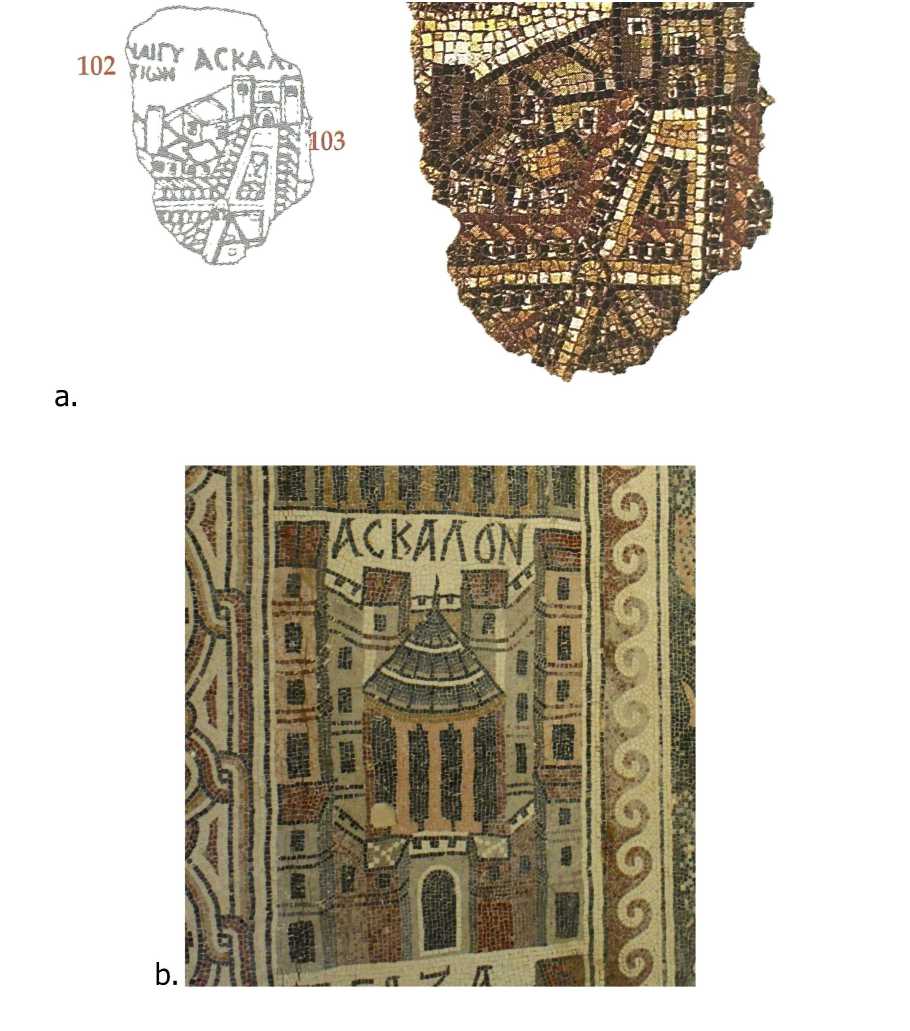

During the Roman period (1st century BCE–4th century CE), Ascalon was renowned as one of the most famous cities (poleis) of Provincia Judaea (Syria Palaes-tina after 135 C.E.), reaching a peak under the Severan dynasty (193–235 CE). Being a lavish Roman city, Ashkelon was dotted with monumental colonnaded or peristyle edifices, temples, a theater, an odeum, public bathhouses, and basilicas4 ( Figs. 1-3 ). One of the city’s basilicas was referred to by Roman travelers as the “Golden Basilica”. In the Talmudic literature, a specific basilica in the town is mentioned, where wheat was sold5. In the 4th century CE, the city gained the status of a Roman colony. During the Early Byzantine period (mid-4th to 7th centuries CE), Ashkelon was a significant Christian center with one or possibly two bishops.6 It was depicted on at least two Early Byzantine ecclesiastical mosaic floors: in Madaba7 and Umm al-Rasas8 ( Fig. 4:a-b ). Eight Early Byzantine churches have been identified in archaeological excavations within the borders of the Roman Ascalon and across the various neighborhoods of the modern city9. Only two of these can still be seen today ( Figs. 5-6 ).

The architectural elements on display date to the Roman and Byzantine peri-ods10. They are grouped in the article into four assemblages (“families”), according to their type, style, and dating, and they will be described accordingly. All presented elements formed part of colonnaded architectural edifices from the Roman and Byzantine periods and originated, according to rare archival photos, in various parts of the Ashkelon district, including Tell Ascalon (now part of the modern National Park of Ashkelon). The ecclesiastical elements were most probably revealed in the churches of Ascalon-Barnea (in the territory of modern Afridar). Most interesting among them are those that were originally Roman constructive elements dating to the 1st–2nd centuries CE and were later reshaped and reused in the churches. The elements were carved from different stone species: most of the architectural elements were carved from light grayish Proconnesian or Phrygian marbles. These marbles were quarried continuously on Marmara Island and in Anatolia during the Roman and Byzantine periods.11 Only the details with Greek inscriptions were published in various articles and monographs (references will be provided accordingly), while the remaining items have never been published be-fore12.

Fig. 1. Ascalon, the Severan basilica. After: Boehm et al. 2016, 293, Fig. 16.

Fig. 2. View of the Severan Basilica in 2017. Photos of the author.

Fig. 4. a. Ascalon on the Madaba mosaic map (5th century CE).

From: Alliata 1998, 86. Courtesy of Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Photographic Archive; b. Ascalon on the mosaic within St. Stephan church, Umm al-Rassas (dated to 756–785 CE). Photo of the author.

Fig. 5. Church of “Green” Mary in Ascalon. Byzantine, rebuilt during the Crusader period. Photo of the author.

Fig. 6. Chapel in Afridar-Ashkelon. Photo of the author.

Four “Families” of the Architectural Artifacts

-

I. The “Purely” Roman details

The first group consists of “purely” Roman details. These are four Corinthian capitals and three segments of granite column shafts (displayed outside of the courtyard), which originated in the basilica, odeum, streets, or forum of the city of Ashkelon.13

– Corinthian capitals.

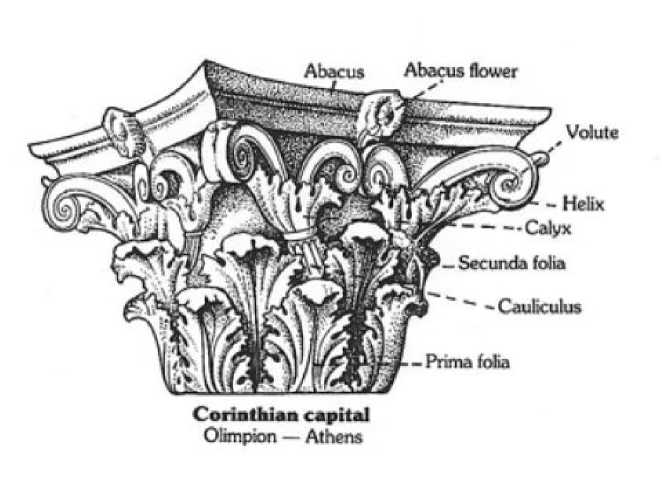

Fig. 7. Classical Corinthian capital and its parts.

From: Jacoby, Talgam 1988, 9, Fig. 3. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The marble Corinthian capitals (nos. 1-4; Figs. 8-11) are comprised of two rows of spiky acanthus leaves of the Asiatic type (named by Ward-Perkins “Asiatic Corin-thian”14). Three of the four capitals (nos. 2, 3, and 4; Figs. 9-11) might be attributed to the type of the Middle/Late Roman capital with double helices15. The capitals of this type were still in use in the early 4th century CE and they were of various scales16. Capitals of this type were revealed at Tel Ascalon within and near the Sev-eran Basilica (excavated at the spot of the modern National Park)17, and in plenty of other Roman sites of the Land Israel and of Asia Minor (Smyrna, Sagalassos, Ephesos, etc., dated to the end of the 2nd century CE). The helices, calyces, and fleurons are of different types or asymmetrical, even on the same capital (especially on capital no. 1, Fig. 8). These features give the impression that the artisan had some freedom in decorating relatively standard capitals. According to the scale, the capitals nos. 1-4 are considerably smaller in scale than the 22 capitals suitable for the inner colonnade of the Severan Basilica (their height was 0.85-0.90 m, and the diameter 0.74 m)18. Also, they are different in scale. They could originate either from the scaenae frons or the second floor of the basilica (the second floor and attic were suggested by M. Fischer19) or from another urban building that is not excavated yet or lost in oblivion (the other basilica, odeum, forum, or colonnaded streets (cardos and decumani)). One capital (no. 4, Fig. 11) is carved from dark gray marble, apparently from Moria quarry in Lesbos. One such capital was found in Roman Ascalon20.

Fig. 8. Corinthian capital, item no. 1. Photos and processing by the author. Proconnesian marble. Meas.: h 0.85 m, w 0.80 m, d 0.50 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7391.

Fig. 9. Corinthian capital, item no. 2. Photos and processing by the author. Proconnesian (?) marble. Meas.: h 0.57 m, w 0.80 m, d 0.35 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7390.

Fig. 10. Corinthian capital, item no. 3. Photos and processing by the author. Proconnesian (?) marble. Meas.: h 0.70 m, w 0.60 m, d 0.38 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7390.

Fig. 11. Corinthian capital, item no. 4. Photos and processing by the author. Paros (?) marble. Meas.: h 0.73 m, w 0.90 m, d 0.43 m IAA inv. no. 1947-7388/1947-7368

–

Monolith shafts.

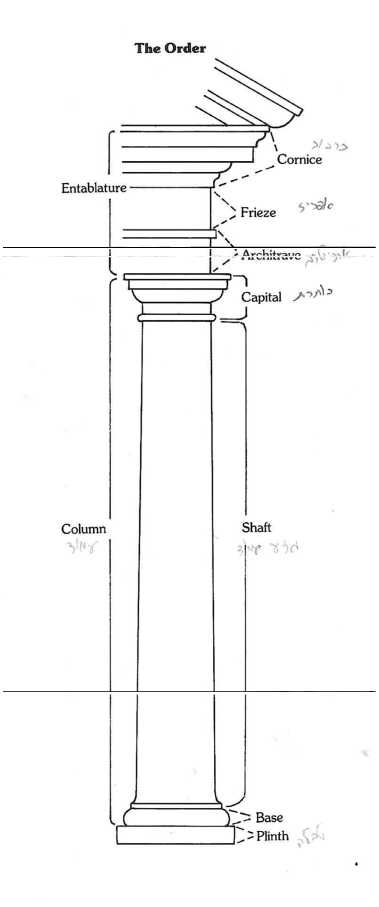

Fig. 12. Classical column set and its parts.

From: Jacoby, Talgam 1988, 7, Fig. 1. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Fig. 13. Column shafts, items nos. 5, 6, and 7.

Photo and processing by the author. Troad gray granite.

Meas.: no. 5 – h 1.91 m, d ca. 0.45 m; no. 6. – h 1.87 m, d upper 0.393 m, d lower 0.44 m; no. 7 – h 1.42 m, d upper 0.47 m, d lower 0.52 m.

The three segments of monumental column shafts on display (nos. 5, 6, and 7, Fig. 13 ) were carved from Troad gray granite. The left segment comprises the middle part of the shaft, while the middle and right segments are the upper and the lower parts of the shaft, as indicated by their proportions and moldings ( entasis, apophyges superior and inferior, Fig. 12 ).

This type of granite was quarried in Northwestern Anatolia, in Asia Minor, and transported throughout the Mediterranean area and as far as the hinterlands of the Near East during the first and second centuries CE21. These quarries, and the workshops that operated within them, were one of the largest monopolies on architectural elements in the Roman world. The shafts were created according to a standard scale, matching the other parts, such as capitals and bases, which were carved in other quarries (Nicomedia, Proconnesus, Phrygia, etc.). It is noteworthy that these shafts may fit several of the Roman marble capitals on exhibit. Dozens of such granite shafts are scattered throughout the ancient site of Ashkelon, probably originating from the colonnaded streets or the forum of the polis. Troad granite shafts were revealed in Jerusalem, Beth Shean, Tiberias, Hippos-Susita, Caesarea, Apollonia, and many other Roman sites in the Holy Land.

-

II. The Roman-Period Spolia Group

This set consists of three Middle and Late Roman elements bearing Greek inscriptions (items nos. 8, 9, 10, Figs. 15-18 ). Unlike the other items presented at the exhibition, these are more well-known and have been published. All these Early and Middle Roman elements bear traces of secondary use in later periods.

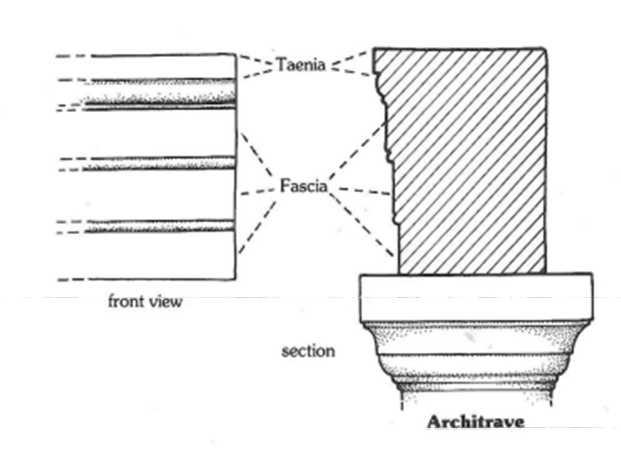

Fig. 14. Architrave and elements of its decoration in Greco-Roman and Byzantine tradition. From: Jacoby, Talgam 1988, 11, Fig. 5; 26. Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

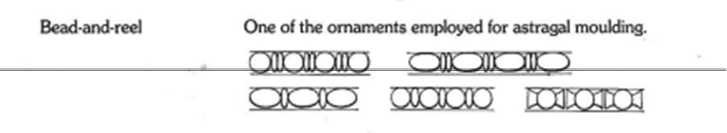

Fig. 15. Architrave reused as a block with the inscription, item no. 8.

Photos of the author. Afyon or Aphrodisias marble. Meas.: h 0.28 m, w 0.70 and 0.50 m, d of the medallion 0.26 m; letters ca. 0.055 m.22 IAA inv. no. 1947-7398.

After Ameling et al. 2014, 270-271, no. 2334.

Fig. 16. Architrave reused as a block with the inscription, item no. 8. Photos from the British Mandate Archive

(folder Ascalon II, SRF_12(158_158)).

This short segment of the marble architrave fragment (no. 8, Figs. 15-16 ), which initially bore three fasciae and two bead-and-reel astragali ( Fig. 14 ), was sawn to be reused. On its long lateral side, the plain, flat wreath, flanked by two broad-pointed acanthus tendrils, was carved. The patterns are relief but blocked out; the background is covered with claw chiseling traces and dots. Within the wreath, the Greek acclamation is engraved (dated by epigraphic features to the 4th century CE). The marble was quarried in present-day Afyon or Aphrodisias. It was unearthed during the British excavations of 1920–1922 within the Roman basilica. The item was often published because of its famous inscription. It is believed that the architrave initially adorned the odeum scaenae frons or some other part of the basilica, together with several similar architrave blocks found in Ascalon.23

ΑΥΞΙ

ΑΣΚΑΛ

ΑΥΞΙΡΩ

ΜΗ

Αὔξι | Ἀσκάλ(ων), | αὔξι Ῥώ|μη

“Advance Ascalon, advance Rome”

The inscription, its reading, and translation are cited after Ameling et al.24

Fig. 17. Column with a Greek Inscription, item no. 9.

Photos of the author and from the British Mandate Archive (folder Ascalon II, SRF_12(158_158)). Proconnesian or Phrygian marble. Meas.: h 0.95 m; d 0.49 m; letters 0.054-0.075 m.25 IAA inv. no. 1951-146.

This lower segment of a Roman column shaft (traces of apophyge inferior in the lower part are noticeable) is inscribed with a Greek inscription (no. 9, Figs. 17 ). It was found near the Byzantine church in Ashkelon-Barne‘a. It was sawn and reused as a lintel.

ΕΙΣΘ[--] ΝΙΚ[--] ΙΟΥΛΙ[--] ΕΞ[.]

-

25 After Ameling et al. 2014, 262-263, no. 2326.

εἷς θ[εός]. | νίκ[α,] | Ἰουλι[ανέ].| (ἔτους) εξ[υ’]

“One God. Iulianus, be victorious! In the year 465” (=361/2 CE)

Only two digits of the date are mentioned in the inscription, but it was convincingly reconstructed from the historical context. It corresponds to November 361/362 CE, when the Roman Emperor, Julian the Apostate (November 3, 361–June 26, 363) was in Antiochia, shortly before his death. This inscription testifies that the population of Ascalon supported Emperor Julian in his brief revival of paganism during the rapid spread of Christianity. The inscription, its reading, and translation are cited after Ameling et al.26

Fig. 18. Column with a Greek Inscription, item. no. 10.

Photos of the author and from the British Mandate Archive (folder Ascalon II, SRF_12(158_158)). Proconnesian or Phrygian marble.

Meas.: h 0.67 m, w 0.29 m, d 0.25 m; letters 0.035 m.27

IAA inv. no. 1958-66.

This lower segment of a Roman column bearing a Greek proclamation was sawn at a later stage, destroying part of the inscription (item no. 10, Fig. 18). According to the mason’s mark “H,” the inscription was engraved on the eighth column of the colonnade. It was inscribed during the reign of the Roman Emperor Commodus (Summer 177–December 31, 192 CE).

[--]ΜΜΟΔΟΥ

[--]ΥΣΕΒΑΣΤΟΥ

[--]+ΕΞΑΜΗΝΟ[.]

[--]ΑΠΟΛΛΟΔΟ[...]

[--]ΜΙΛΤΙΑΔΟΥ

[--]ΥΠΡΟΕΔΡΟ[.]

Η

[ἔτους ιβ’? Κο]μμόδου | [Ἀντωνείνο]υ Σεβαστοῦ | [τοῦ κυρίου] β’(?) ἑξαμήνο[υ | ἐπὶ] Ἀπολλοδό[του | τοῦ] Μιλτιάδου | [ἐγερσίτο]υ προέδρο[υ] | η’

“In the twelfth year of Commodus Antoninus Augustus, our Lord, in the second (?) half of the year, when Apollodotus son of Miltiades was responsible for the work when he was prohedros. Eighth”

The inscription, its reading, and translation are cited after Ameling et al.28

-

III. The Byzantine-Period Spolia Group

This group comprises Roman architectural elements that were reshaped and reused in Byzantine monumental edifices, such as churches (nos. 11 and 12, Figs. 20-21 ).

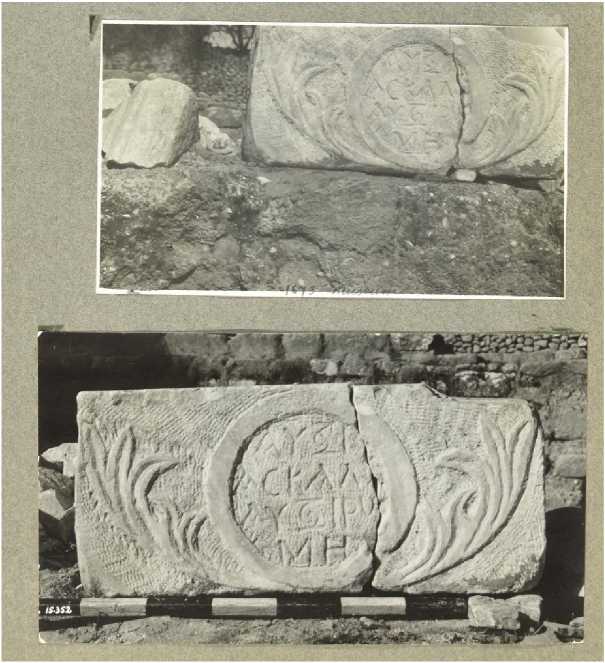

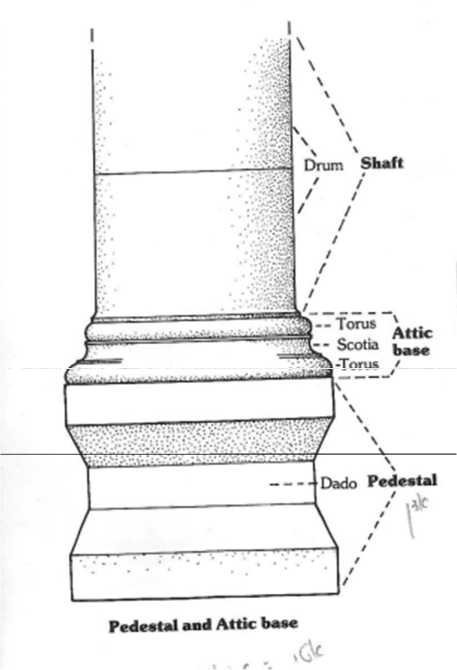

Fig. 19. Classical pedestal with the attached Attic base and the lower drum of the shaft. After: Jacoby, Talgam 1988, 8, Fig. 2.

Courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

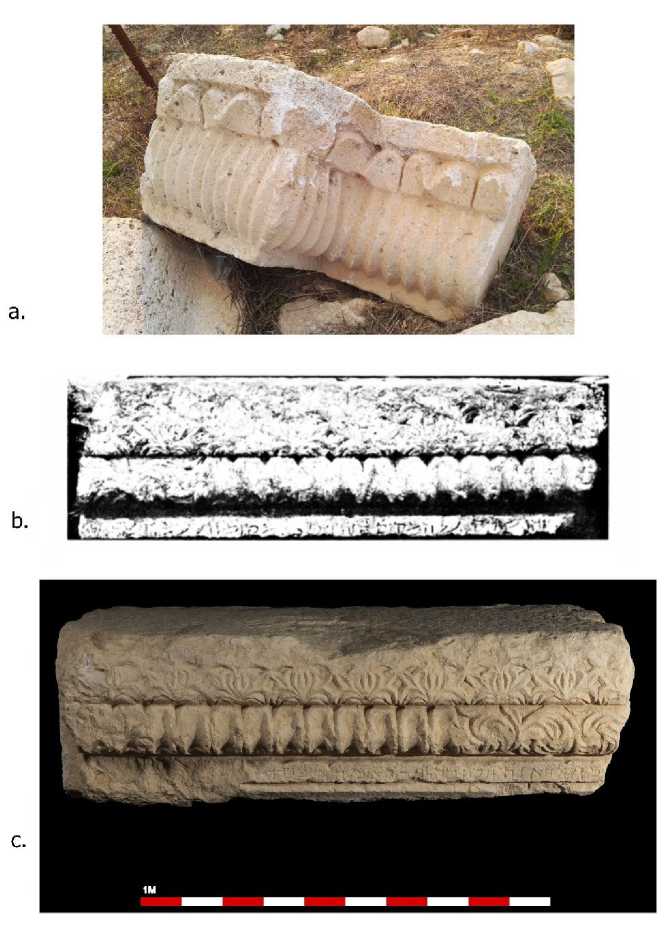

Fig. 20. Roman Attic base reused as a Byzantine cornice, item no. 11. Photos of the author. Phrygian (?) marble.

Meas.: h 0.26 m, w 0.68 m, l 0.90 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7411.

Fig. 21. a. Fluted capital and cornice in Burj Beitin. Photo of A. Zelikman. b. First segment of the fluted frieze from the synagogue in ‘Alma. From: Hachlili 2013, 475, Fig. X-1:b. c. Second segment of the fluted frieze from the synagogue in ‘Alma (IAA no. 1958-730). Photo: E. Ostrovsky. Courtesy of Israel Antiquities Authority.

The architectural element on display was originally a Roman Attic semi-base, which was turned upside down. On its rear side, the fluted cornice (cyma reversa) with a hidden cross among the short flutes was carved (no. 11, Fig. 20). The round (moon-like) moldings (so-called cablings) within the flutes show their bottom part. Between the flutes are stands with gems instead of arisses (ribs). The fluted cornices are known from Hellenistic and Roman times in local and regional archi-tecture29; however, only Late Antique/Byzantine parallels will be mentioned here.

Several fluted architectural fragments are associated with the Late Antique synagogues in the Golan and Galilee. The arch of the basalt niche in the Khorazim synagogue is decorated with a row of short flutes.30 The fluted frieze was revealed in secondary use in the wall of the late house in Yehudiyye. The fragment is currently on site. It was published only on the Israel Antiquities Authority's archaeological survey map website.31 The existence of the Late Antique synagogue in this settlement is attested by a rich collection of architectural remains scattered across the site, which were secondarily reused in later houses.32 Another flattened fluted frieze was revealed in the secondary use in Hoha, where the secondarily used architectural elements suggest the existence of a synagogue.33 The flutes bore cablings from both ends (upper and lower), which is a very unusual, unclassical feature. Two fragments of the same molded, convex, fluted frieze with the Hebrew-Aramaic inscription are known from the village of 'Alma, which is near Kafr Baram (Fig. 21:b). One of the two known fragments (with the beginning of the inscription) was revealed in 1914 and is currently located in the modern synagogue in 'Alma. The second fragment (containing the middle section of the inscription) was discovered in 1957 and is presently in the IAA treasure department (IAA inv. No. 2025537). The frieze with the end of the inscription is still missing.34 The flutes of the frieze are convex, plump, and with cablings. A very similar frieze with identical moldings and sections was found in Roman Byblos.35 In the Capernaum synagogue, the fluted ornament was applied in a very interesting way: the protruding imposts attached to the peopled scroll frieze were adorned with flutes from both lateral sides. They were convex in both transverse and longitudinal sections and bore prominent cablings at the lower ends.36

Only one fluted member might be associated with the local Early Byzantine churches. It was found in secondary use in Burj Beitin, near the hypothetical remains of the Byzantine church.37 The element belonged to the squared pilaster cap, which was incorporated into the continuous frieze. Both the cap and the frieze were adorned with the reeded/fluted ornament, with convex section ( Fig. 21:a ).

Marble fluted cornices and friezes are known in Asia Minor, for example, in the church of St. Michael at Miletus in Caria38 or in the Arslanhani camii in Ankara in secondary use.39 Some fluted capitals are also known in Syria. The capital with the twisted flutes tapering towards the bottom was found in the 5th-century CE dwelling in Kokanaya.40 In the church of St. Simeon in Qalat Siman, the impost, friezes over the column, and arcuated friezes over the entrance (late 5th century CE)41 were decorated with short flutes.

2Й®Й®*

Torus ' .

с .. Attic

Scot,a base

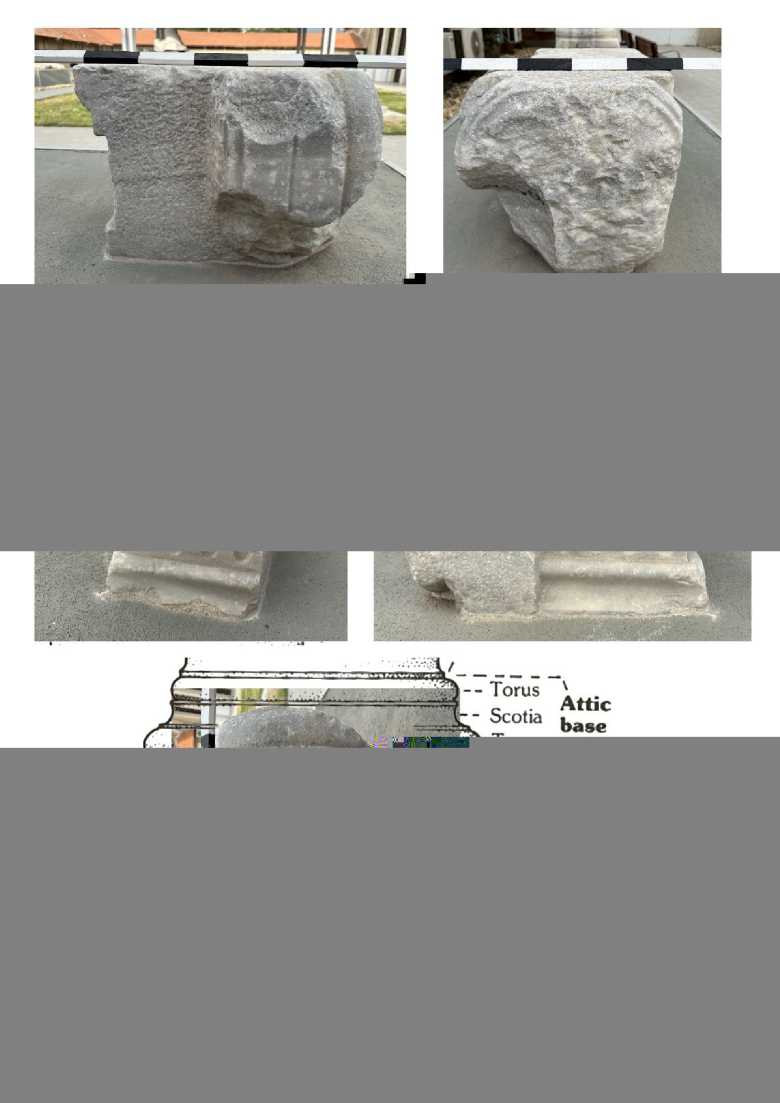

Fig. 22. Roman Attic Base reused as a Byzantine fluted pedestal, item no. 12. Photos and processing by the author. Phrygian marble.

Meas.: h 0.37 m, w 0.38 m, l 0.49 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7412.

Fig. 23. Roman pedestals found near the Severan Basilica and scattered at the site of the modern city of Ashkelon. Photos of the author.

The original Roman Attic base, with a squared pedestal, was sawn and chiseled on three of its sides in the Byzantine period, preserving only the rounded torus and part of the cornice (no. 12, Fig. 22 (see also Fig. 19)). Similar complete pedestals were found near the Severan Basilica of Ashkelon and vicinity42 (Fig. 23). In the Early Byzantine period, the semi-pedestal of a smaller scale was carved on the bottom side of the pedestal under consideration (no. 12). It was decorated with a molded cornice, base, and a fluted dado between them. The cablings are showing the bottom part of the pedestal (it is presented in the upside-down position). Apparently, the pedestal was incorporated in the same edifice as the fluted cornice, presumably a church (item no. 11, Fig. 20). The style of the fluted pedestal is Byzantine, though the typologically close parallels among the local architecture are known only from the Crusader Church of Nativity in Bethlehem (Bagatti 2002, Pls. 2, 4).

The secondary use of architectural features (spolia) is a well-documented phenomenon in the archaeology of Israel, discussed by M. Fischer43, among others.44 From Jerusalem, the trend is well known, as evidenced by the Temple Mount excavations, which have revealed many Herodian and Roman architectural details integrated into Byzantine and Early Islamic buildings, as well as Byzantine elements incorporated into Umayyad structures.45 Mainly, these spolia in Jerusalem architecture were used as building stones for constructive purposes, except for the Byzantine lintel in the wall of the Umayyad palace near the Temple Mount and the chancel screen panel with stephanostaurion in the wall of the Dome of the Rock mosque. This practice contrasts with the use of ancient details in buildings for aesthetic or ideological purposes, such as manifesting the victory of a new religion over an older one, such as the victory of Christianity over Paganism or Islam over Christianity.46 In these cases, the spolia were incorporated into edifices to create stylistic accentuations, for example, Roman items in Late Antique synagogues and Byzantine items in Early-Islamic mosques, “archaized” their decorative style.47 In the territory of the Land of Israel, Roman details were reused in churches at Hip-pos-Susita, Tabgha, Shiloh, and elsewhere; additionally, Roman spolia decorated Late Antique synagogues in Capernaum, Baram, Khorazim (?), Rehov, and else-where.48

-

IV. The “Purely” Byzantine-Period Group

The last group of elements consists of the “purely” Early Byzantine elements, which were manufactured specifically for ecclesiastical decoration. They all comprise column sets of different scales.

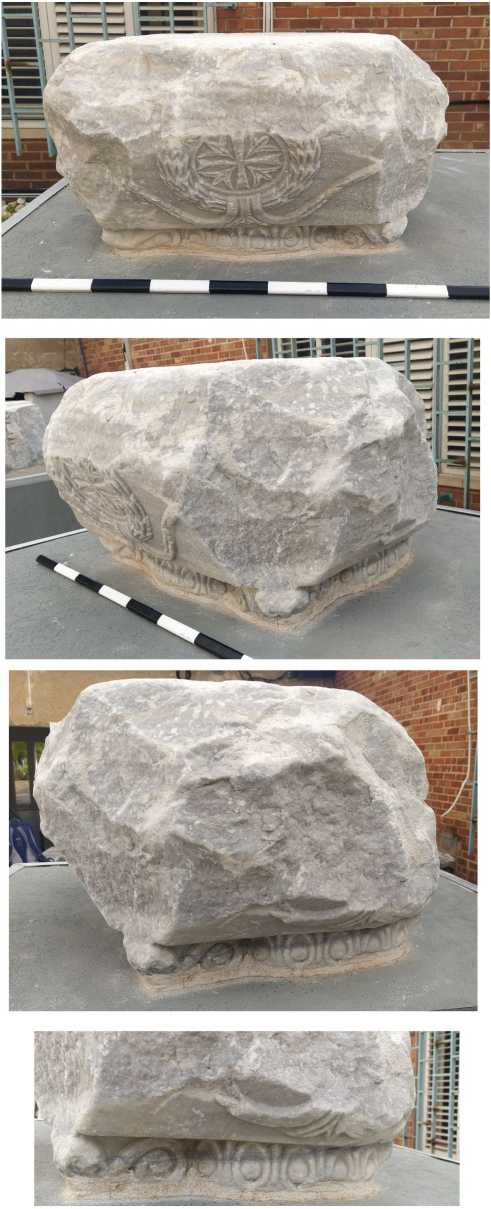

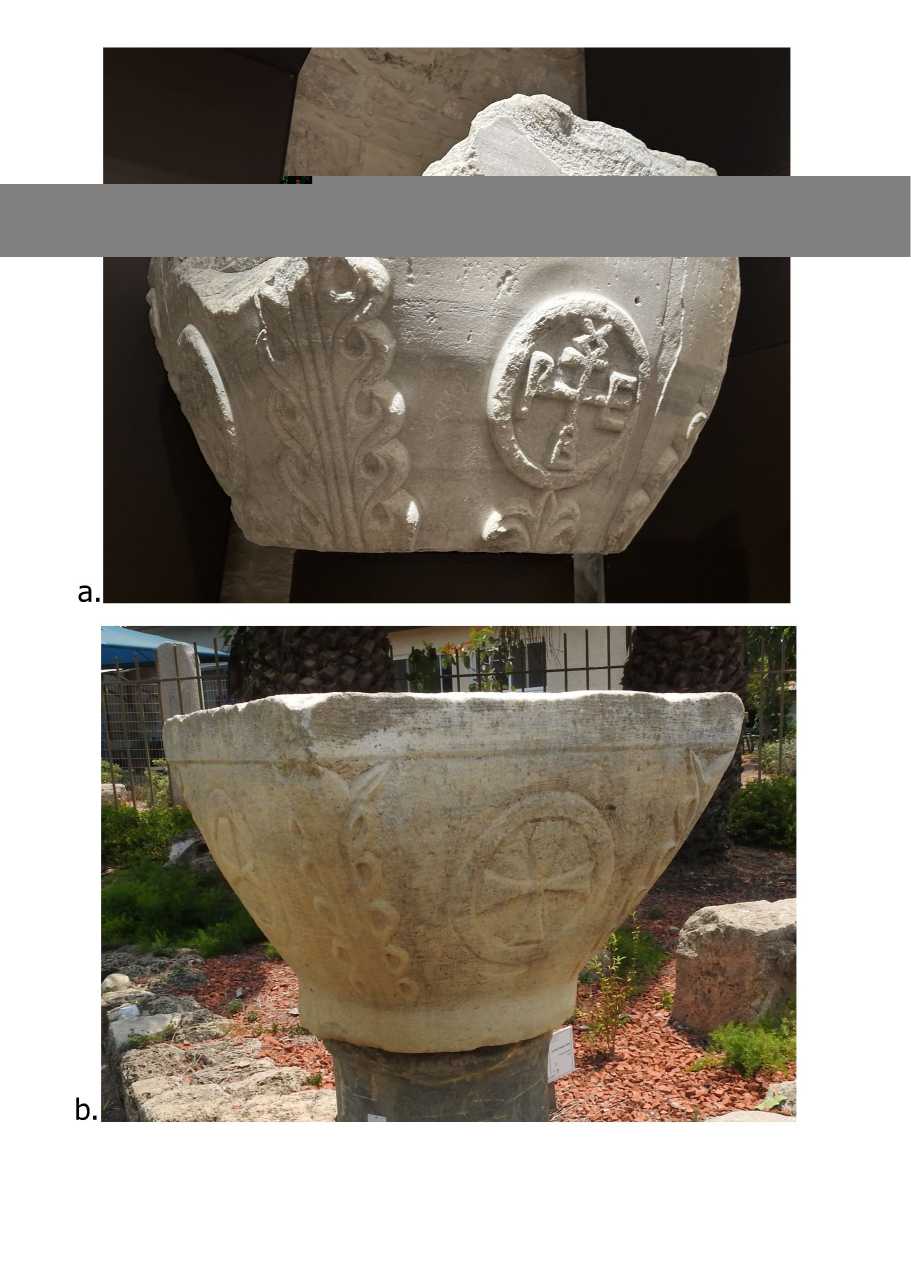

Fig. 24. Marble Byzantine Impost Capital, item no. 13. Photos of the author.

Proconnesian or Phrygian marble. Meas.: h 0.40 m, w 0.75 m.

IAA inv. no. 1947-7430.

Fig. 25. Impost capitals: a. originated from the Holy Sepulchre (currently in the Flagellation Museum in Jerusalem); b. unprovenanced, presented in the Museum in Sdot Yam. Photos of the author.

This large impost capital is an unusual find in the Land of Israel (no. 13, Fig. 24 ), with only a few similar examples, four of which originated in the Holy Sepulchre church in Jerusalem.49 Another one is on display at the museum in Sdot Yam ( Fig. 25 ). Many other parallels are known from churches in Constantinople, Asia Minor, and Greece. The impost capital comprises a heavy pyramid, which is truncated in its upper part, and an egg-and-dart collar in its lower part; small volutes emphasize its corners. A unique feature depicted on this capital is the stephanostaurion composition: a wreath with a cross flanked by two ivy tendrils. It is well-preserved only on one side, yet chiseled out on the other sides. This composition usually adorns chancel-screen panels rather than capitals. Still, some parallels can be observed among the Early Byzantine art of Asia Minor.50

This Early Byzantine Corinthian capital is adorned with two rows of broad acanthus leaves, only four in each row. The leaves are stylized, forming geometrical figures between the lateral lobes. Sometimes, the tips of the leaves touch each other, creating masks. Hence, this type of leaves was called “mask-acanthus” (“broad-pointed”)51. The volutes join in the center of each side of the capital and form a V-shaped figure, corresponding to the so-called V-type Corinthian capital, which was very popular in early Byzantine art.52 The abacus is decorated with a row of semicircular petals on all four sides. The fleurons are adorned with crosses of different shapes. Similar V-type capitals were found in seven churches in the Holy Land, including the church in Ashdod-Yam/Azotos Paralios.53 Some other V-type capitals are scattered in the territory of the modern Ashkelon, in ancient Apollonia and Caesarea. They lack firm context and remain unpublished.

Fig. 26. Marble Byzantine Corinthian capital, item no. 14. Photos of the author. Proconnesian or Phrygian marble. Meas.: h 0.43 m, w 0.61 m, d 0.38 m; IAA inv. no. 1947-7430.

Fig. 27. Marble Byzantine Corinthian Capital, item no. 15. Proconnesian (?) marble. Meas.: h 0.30 m, w 0.50 m, d 0.28 m.

This small Corinthian capital consists of four mask-acanthus leaves and is dated to the Early Byzantine period based on its style. Due to its size, it likely belonged to a small colonnaded structure, such as a second-floor gallery, a portico, or a cibo-rium. Forty-two Corinthian capitals of a similarly small scale were found in 22 local churches in the Holy Land, and there is no chance to mention the best part of them here. A very similar small capital, also with four acanthus leaves, is displayed at the other open-air exhibition in Afridar. Both small capitals might originate from the same church, and apparently from the same small colonnaded structure.

Fig. 28. Marble column with the wreath, item no. 16. Meas.: h 2.34 m, d 0.28/0.33 m, d of the wreath 0.21 m. Proconnesian or Phrygian marble.

Fig. 29. Marble column with the octagonal pedestal and incised wreath with the cross in the open-air exhibition in Afridar (Roman spolium?). Photos by the author.

The complete marble column on display is carved in Classical and fine Roman style. It narrows toward the top ( entasis ) and features moldings at the top and bottom edges ( apophyges superior and inferior ). However, the column is safely dated to the Early Byzantine period, as it bears an indicative wreath with a defaced cross, with its traces still visible. As the decoration is in relief, it was carved together with the column, not during its secondary use. Such wreaths usually adorn chancelscreen panels in churches. The only other similar shaft, decorated with a relief wreath comprised of two laurel branches tied by Heracles's knot in the lower part, and with the relief cross within it, was described (though not illustrated) by

D. Pringle in the church in Er-Ram, which is to the north of Jerusalem.54 A similar medium-sized shaft, though with an incised, not relief, wreath adorned with a chevron pattern and a cross (defaced) within it, is on display in the other open-air exhibition in Afridar (near the seashore, Fig. 29 ). The column's integral pedestal is octagonal. Such a polygonal pedestal was formed during the secondary use of the pier from the rectangular (?) pedestal. Apparently, the incised wreath and the cross were also added during this reshaping. So, the column was quarried during the Roman period and reshaped during the Early-Byzantine one. Such medium-sized columns with octagonal pedestals were usually used for ciboria in the churches. So, these are the only three examples of the shafts with the relief wreaths known in the territory of the Holy Land.

Two pedestals dating to the Early Byzantine period are on display (items nos. 17-18, Figs. 30-31 ). The first one pedestal comprises a molded cornice and base with a low squat dado between them, which is topped by an Attic base (two tori and scotia between them, see Fig. 19 ). Its upper diameter fits marble column no. 16 ( Fig. 28 ), indicating that they may have formed one column set. The column set of such scale could belong to the portico of the church or other urban edifice.

The dado of this pedestal, no. 18 (Fig. 31), is slightly larger and higher than that of pedestal no. 17 (Fig. 30). Defaced crosses are noticeable on all its sides. The pedestal is topped by a plain, roughed-out Tuscan base (torus and drum of the shaft). On the upper facet, there is channeling and a hole for affixing a column by means of a lead dowel. The crosses were defaced by iconoclasts, but it is still not clear whether it was an Islamic or Christian initiative, as iconoclasm in both religions coexisted in the same period and, in the case of the Syro-Palestinian province, in the same territory. A similar pedestal, adorned with relief crosses that were not defaced, was revealed near Tel Ascalon (Fig. 32). It is now displayed near the Sev-eran Basilica in the National Park. Apparently, it derives from one of the local churches. Additionally, in Ascalon, a pedestal adorned with a relief menorah, lulav, and etrog was revealed.55 These exclusively Jewish symbols provide the pedestal with the firm context of a synagogue. Pedestals are known from several churches in Jerusalem, for example, one pedestal was revealed in the church of the Agony in Gethsemane56, five in the Church of St. Mary in Probatica57, and many pedestals of various scales in the Holy Sepulchre (some in secondary use as a capital on the second floor of Anastasis).58 In the Crusader church of St. George in Beth Govrin (Eleutheropolis), 22 Byzantine pedestals (counted by the author) were secondarily reused. They are only briefly mentioned in the publication59. The pedestals were frequently found decorating Late Antique synagogues in the Galilee and Golan, and churches of the Roman province of Phoenicia, which includes part of the Upper Galilee.

Fig. 30. Marble Byzantine Pedestal, item no. 17. Photos of the author.

Meas.: h 0.50 m, w 0.33 m, d (upper) 0.25 m.

Proconnesian or Phrygian marble.

Fig. 31. Marble Byzantine Pedestal with defaced crosses, item no. 18.

Photos of the author. Proconnesian or Phrygian marble. Meas.: h 0.60 m, w 0.50 m, d 0.40 m; IAA inv. no. 1947-7381.

Fig. 32. Early Byzantine pedestal in ancient Tel Ascalon. Photos of the author.

The present collection of architectural details presented in the article is only a part of the rich archaeological heritage of Roman and Byzantine Ascalon, which remains to be subjected to profound systematization and research.