Geometric creativity of Ajami ibn Abubakr Nakhchivani

Автор: Andrei Shchetnikov

Журнал: Schole. Философское антиковедение и классическая традиция @classics-nsu-schole

Рубрика: Статьи

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.20, 2026 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article examines the geometric patterns that decorate three mausoleums from Nakhchivan, built in the second half of the 12th century. The architect of two mausoleums was Ajami ibn Abubakr, and the third mausoleum was also built either by him or by someone from his school. Among these patterns are simple and well-known ones, as well as complicated and original ones, undoubtedly invented by him. For each pattern, its structure and the possible idea of its invention are discussed.

Ajami ibn Abubakr, Nakhchivan, Islamic geometrical patterns, medieval Islamic architecture

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147252943

IDR: 147252943 | DOI: 10.25205/1995-4328-2026-20-1-200-216

Текст научной статьи Geometric creativity of Ajami ibn Abubakr Nakhchivani

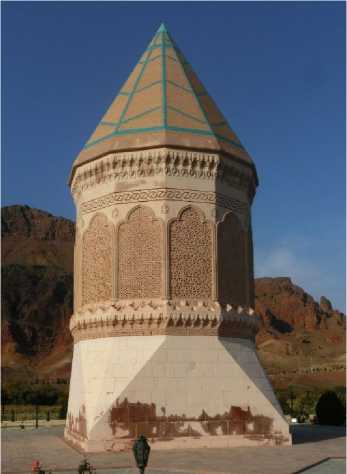

Description of three Nakhchivan mausoleums

In a green park in the center of Nakhchivan there is a tall beautiful brick decagonal tower. Its height is 25 meters, but once it was even higher, crowned with an outer pyramidal dome. Now the tower is covered with an inner semicircular dome and a metal roof above it. The top of this tower is belted by an inscription, which says that Atabeg Jahan Pahlavan ordered to build this tomb tower for his mother Momine Khatun in 1186. The architect of the mausoleum also is named here. He was Ajami ibn Abubakr, and he included in this inscription the proud words that carry two meanings at once: “We will die, but this will remain.”

The high niches of each of the ten sides of this mausoleum are decorated with different geometric patterns. The patterns are laid out with bricks protruding from the wall, and the spaces between bricks are filled with carved stucco. Some patterns are decorated with inserts of blue bricks glazed with turquoise.

ΣΧΟΛΗ Vol. 20. 1 (2026) © Andrei Shchetnikov, 2026

Half a kilometer from here, on a small square among low-rise buildings, there is another octagonal mausoleum with a pyramidal outer dome. Its inscription says that Yusif ibn Kuseyir was buried here in 1161, and the architect of the mausoleum was the same Ajami ibn Abubakr. This mausoleum, smaller in size, is also decorated with geometric patterns, and all patterns on its edges are also different. The bricks of the ornamental lines stand out against the gray background, and the patterns are easy to read from afar.

Another octagonal mausoleum with a restored pyramidal dome stands on a high stone pedestal in the village of Gulistan, thirty kilometers southwest of Na-khchivan. This mausoleum is decorated with three repeated patterns. There is no documented dating for this mausoleum, and neither the person buried there nor the architect is known. But the mausoleum in Gulistan evidently was constructed before the Mongol invasion, and it was either designed by Ajami or by a member of his circle.

General characteristics of Nakhchivan geometric patterns

One should not separate the Nakhchivan collection of geometric patterns from the larger context of this art, which originated in the pre-Mongol era in what are now Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. The three Nakhchivan mausoleums, in terms of the richness of their ornamental decoration, are comparable to the two Kharraqan towers or the lost but documented collection of geometric patterns from the palace of Termez rulers. They demonstrate the high and refined level that the art of geometric ornamentation reached by the second half of the 12th century. With the commonality of geometric ideas and motifs, each individual territory contributed its own part to the development of this art. Some of the patterns of Nakhchivan are known in other places as well, but some others are quite unusual and are not found anywhere else. We should examine them all, paying attention to both the common features and the specific regional characteristics.

The patterns of the Nakhchivan mausoleums have already been discussed by Peter Cromwell (2018). The mausoleum of Yusif ibn Kuseyir is observed in detail by McClary (2015), who also discusses the parallels between this mausoleum and its tympanum decorations with the mausoleum of Mengücek Gazi in Kemah, eastern highland Anatolia, built in 1192. There are also a number of publications in Azerbaijani about the Nakhchevan mausoleums, which unfortunately are not available to me; I am including one of the latest ones in the reference list out of respect for their authors.

As for the method of analyzing geometric patterns that I follow in this paper, I describe not only every pattern itself and its relationship to other patterns but also try to reconstruct how this pattern could have been invented. Of course, in this way we cannot reconstruct the thought of Ajami and other architects in detail, but we can follow the paths of their thought.

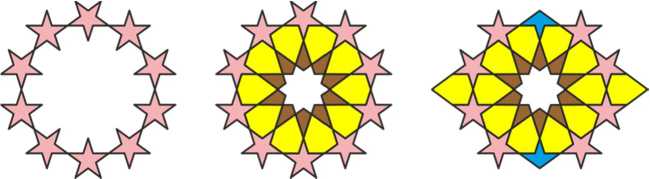

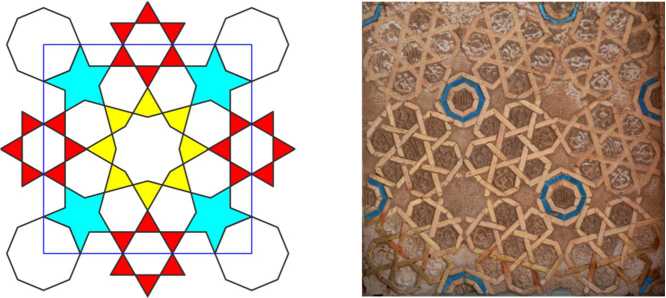

Three patterns of the mausoleum in Gulistan

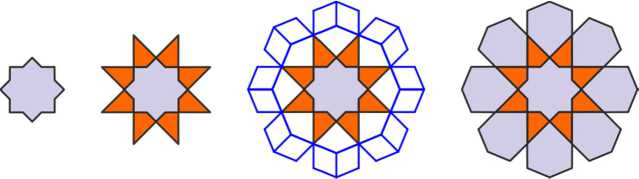

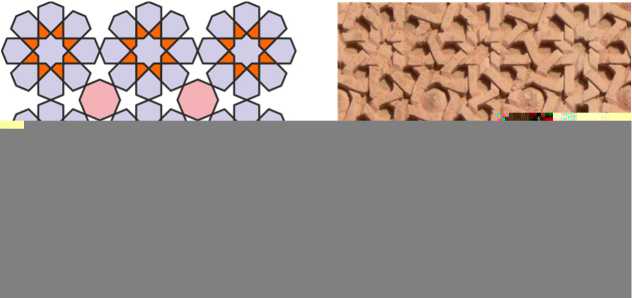

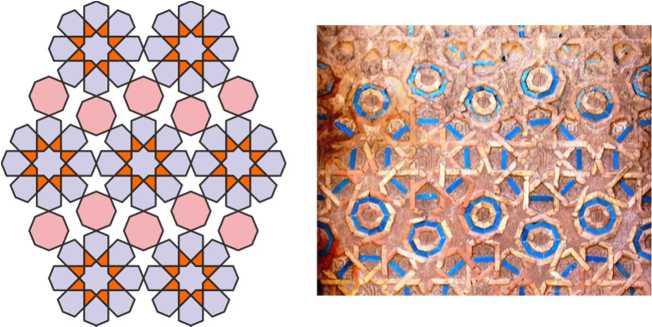

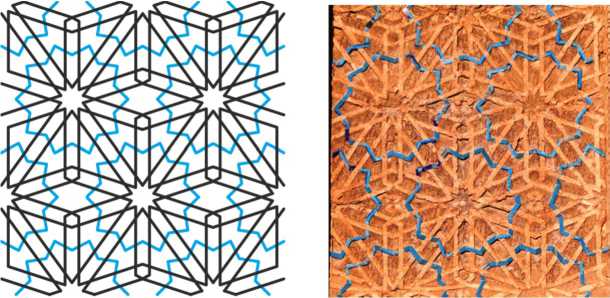

The three geometrical patterns adorning the mausoleum in Gulistan belong to the common fund of this art. To understand how the first pattern is created, we form a necklace of ten five-pointed stars, aligning their rays with each other. Following the borders of the stars into the necklace, we get ten petals at the first intersection and ten rays of the ten-pointed star at the second intersection. Thus, a beautiful ten-petal rosette framed by ten stars is created. We obtain two “paw” figures by cutting off the outer rays of two opposing stars on the vertical axis of this rosette. Along the horizontal axis, we add two inverted petals to the rosette, obtaining a diamond shape with parts of five-pointed stars protruding beyond its boundary.

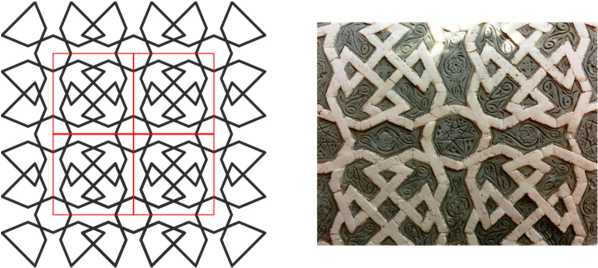

Overlapping such diamonds by their stars, the entire plane can be filled. Finally, each line of this pattern expands to a ribbon, and these ribbons intertwine with each other. This type of pattern is known in Persian as girih , which translates to “knot.”

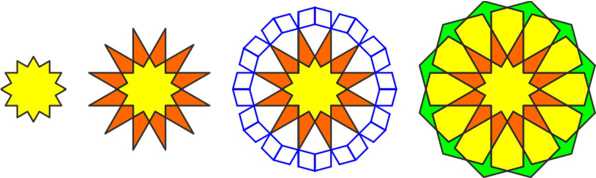

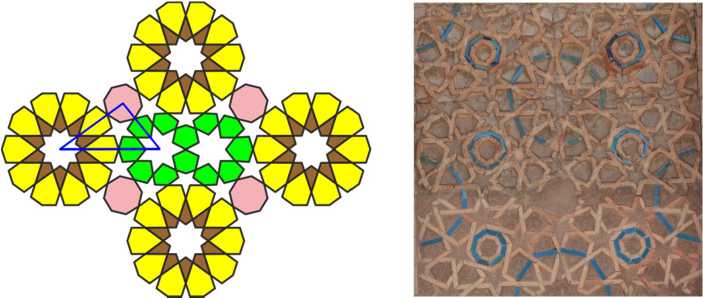

For the second pattern, we begin with 8-pointed star, merging two squares. Continuing the sides of this star, we get another 8-pointed star. Then we describe this star with an octagon, build rhombuses on the halves of its sides, and outline them: this is how the petals of the rosette arise.

Next, four eight-petal rosettes are arranged in a square cell, touching with the tips of the petals, and regular octagon is inscribed between them.

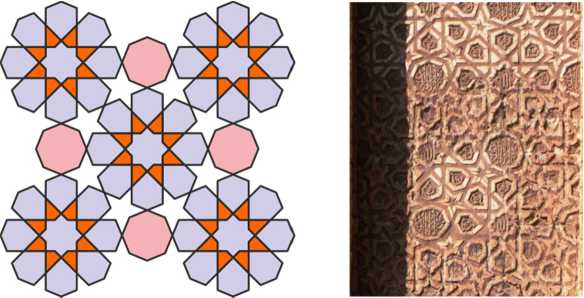

For the third pattern, we begin with 12-pointed star, merging four equilateral triangles. Then we reproduce all steps from the previous construction. This 12-petal rosette is extended from the outside with a necklace of paws, similar in shape to those from the first pattern.

Next, four 12-petal rosettes are arranged in a square cell, touching with the tips of the paws. Four hexagons and central octagon are inserted in the space between them. The lines of the pattern at the contact point between the octagon and the hexagons undergo some bending, but it is not noticeable in the stone.

Other patterns with eight-petal rosettes

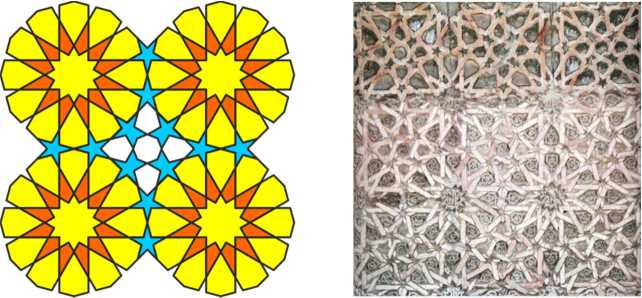

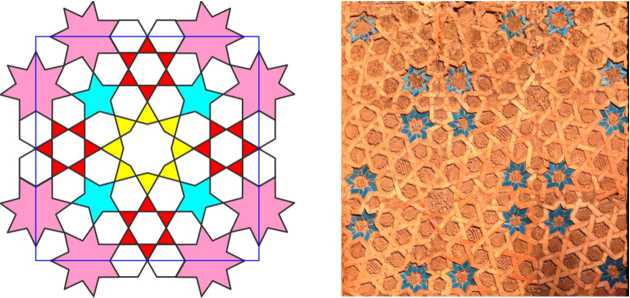

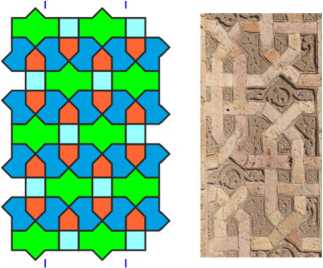

The side of the Momine Khatun mausoleum with the entrance door is decorated with the same pattern made up of eight-petal rosettes and regular octagons as the Gulistan mausoleum. Now this pattern is rotated by 45°, which creates a different visual sensation.

The Momine Khatun mausoleum is decorated with another pattern made up of eight-petal rosettes and regular octagons. The rosettes are arranged in horizontal rows, and the octagonal “snakes” are inserted between them. The octagons and eight-petal rosettes are emphasized on the wall by azure inserts; several other patterns in this mausoleum have this type of decor.

Another rosettes with twelve petals

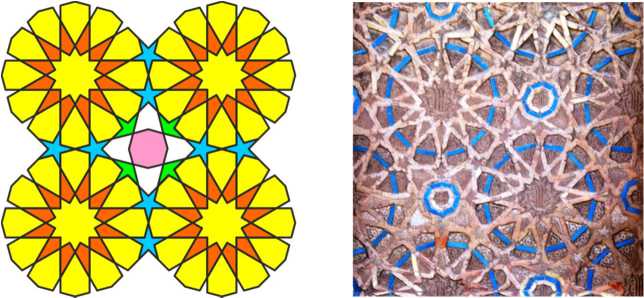

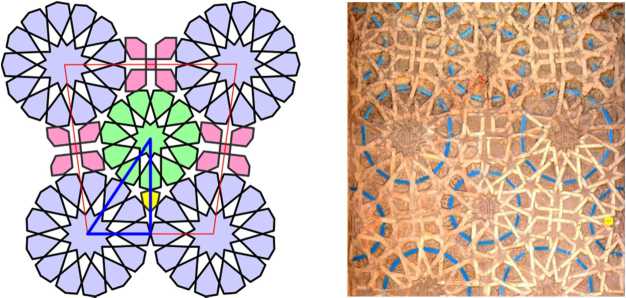

This pattern from the Momine Khatun mausoleum contains the same 12-petal rosettes as the pattern from the Gulistan mausoleum. The difference is that the rosettes are joined now directly by petals. Five-pointed stars of irregular shape adjoin the rosettes, and an octagon is inserted into the space between the stars.

In the second version of this pattern, minor changes are made: instead of irregular stars, the paws are directed into the square window between the rosettes. In addition, this pattern is rotated by 45° on the wall, and blue dodecagons are added to it.

Ten-pointed stars and rosettes with ten petals

There are three patterns with ten-pointed stars in the Momine Khatun mausoleum. All of them are quite unusual: it is clear that their author tried to go beyond the usual and come up with something original.

The first pattern uses ten-petal rosettes with built-on paws. The gaps between rosettes in alternate horizontal rows are filled in two different ways.

The second pattern is a kind of macramé , woven on the basis of small ten-pointed stars, placed in the nodes of a rhombic lattice. From each star, paired lines are released in each of ten directions, and these lines either go to another star along the side of the cell, or go inside the cell and intertwine with each other there through a hexagon. Each small star is outlined by a large blue ten-pointed star, emphasizing the structure of the pattern.

In the third pattern, ten-petal rosettes are connected through octagons, which is quite unusual for the geometric canon. The empty space inside the cell is filled with a pair of seven-pointed stars.

To understand the principle of fitting that underlies this pattern, let us consider a right triangle with its vertices in the centers of the stars, and assume that its sides pass along the axes of symmetry of the corresponding stars and polygons. Now we calculate the sum of the angles of this triangle. If we take the straight angle as unity measure, this sum will be equal to 1/2 + 1/5 + 2/7 = 69/70, but it should be equal to 1. Therefore, there are minor distortions in the structure of this pattern, the angles between the rays of the seven-pointed star are not equal to each other, etc. But these distortions are small, and they are almost imperceptible to the eye.

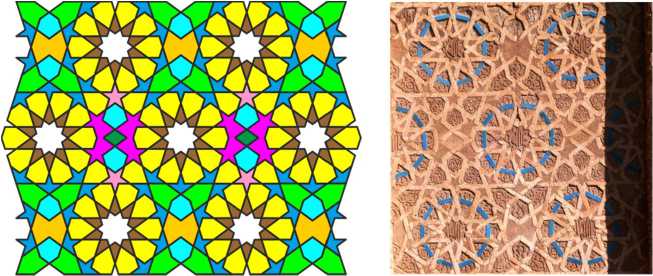

Rosettes with 13 and 11 petals

The next pattern from the Momine Khatun mausoleum is based on the same matching game as the previous one. This is the only pattern in Nakhchivan composed of two different rosettes with 13 and 11 petals. The cell of this pattern has the shape of a trapezoid. In our diagram, the trapezoid with horizontal bases is selected, so the centers of 13-petal rosettes are at its vertices, and the 11-petal rosette lies inside the trapezoid. We can also select a trapezoid with vertical bases, so that the centers of 11-petal rosettes are at its vertices, and the 13-petal rosette lies inside the trapezoid.

Let us estimate the degree of fitting of rosettes in this pattern, calculating the sum of the angles in the selected right triangle, with the same assumptions as for the previous pattern. This sum is equal to 1/2 + 4/13 + 2/11 = 283/286, which is slightly different from 1. Therefore the hypotenuse of the triangle does not coincide with the axes of symmetry of the rosettes, the rosettes themselves do not touch each other with their vertices, etc. But these distortions are almost imperceptible to the eye, especially on the wall.

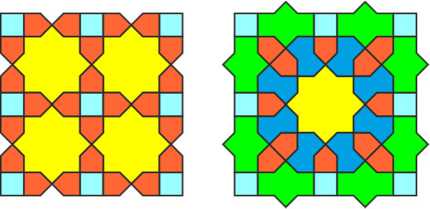

Six-pointed stars in a rotated square cell

The symmetry of individual elements of a pattern is usually adjusted to the symmetry of the pattern itself. If the pattern is built on a grid of equilateral triangles, it is natural to use 6- or 12-pointed stars in it. If the pattern is built on a square grid, it is natural to use 8- or 12-pointed stars (12 is divisible by both 3 and 4, so it is used in both families). But is it possible to use a six-pointed star in a pattern built on a square grid? Probably, it is, but only to the extent that 6 is divisible by 2, placing such stars in the centers of symmetry of the 2nd order.

A simple realization of this idea is found in one of the patterns in the Yusif ibn Kuseyir mausoleum. Small six-pointed stars are placed on the sides of a square cell. The sides of the stars continue inside the cell, creating a pattern with macramé weaving, and the stars are outlined with hexagons. The eight-pointed star that appears in the center of the cell is not regular. In our drawing, the sides of the square cell can be conveniently turned horizontally and vertically; on the wall, this pattern is rotated by 45°, which adds some sharpness to its visual perception.

Among the patterns of the Momine Khatun mausoleum, this idea is found two more times. In the center of the square cell of the first pattern, there is an eight-pointed star with an angle of 60° at its vertices. Four six-pointed stars with their centers in the middle of the sides of the square adjoin this star. In the corners of the cell there are regular octagons. After drawing all the lines, the six-pointed stars are surrounded by hexagonal honeycombs. All of the hexagons, except the central one, are not regular. On the wall, such a cell is rotated by 45° relative to the vertical, as was done in the previous pattern.

The second pattern is more sophisticated. In the center of its square cell there is again an eight-pointed star with an angle of 60° at its vertices. Four six-pointed stars adjoin it, but now the cell border covers these stars entirely. On the sides of the cell there are pairs of regular hexagons. Slightly deformed seven-pointed stars adjoin them. And again, on the wall such a cell is rotated by 45°, and our attention is drawn to the fours of seven-pointed stars, emphasized by the glaze blue outline.

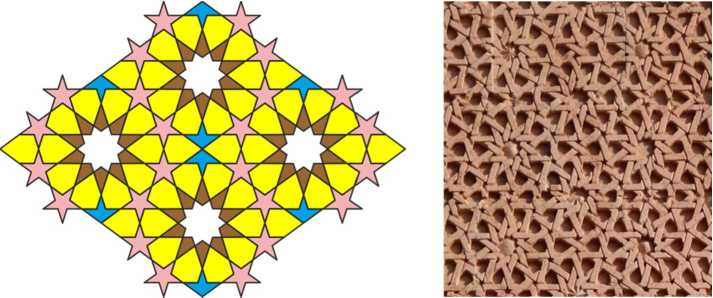

Patterns from a construction set

The next pattern belongs to a large family known since the first half of the 11th century. All patterns of this family are assembled from the set of several mosaic elements, and their base and root is an eight-pointed star obtained by merging two squares. Here are two examples of such patterns.

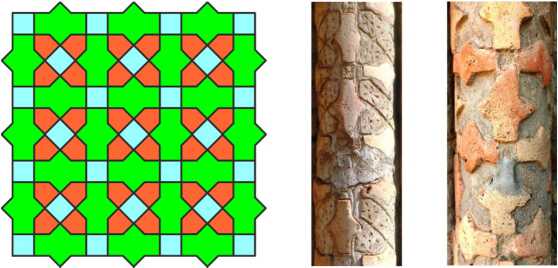

The pattern from the Yusif ibn Kuseyir mausoleum uses three elements from this set: a jug, a house and a bow. Two houses are attached to the ends of the jug, and such composite figures are arranged chequerwise, horizontally and vertically. Еhe spaces between them are filled with fours of bows, twisted also chequerwise, in two directions of rotation.

The next pattern, assembled from the same elements, is on the border in the Momine Khatun mausoleum.

Another pattern from this construction set decorates the columns of both mausoleums. Jugs, houses and squares are used here. Note that the lines of this pattern arise from the superposition of regular octagons.

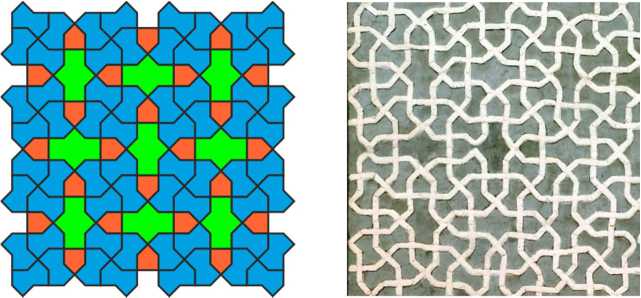

Patterns with superimposed simple figures

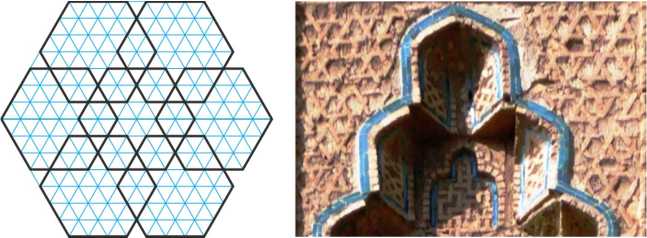

Now we will consider a large group of patterns which are obtained by overlapping simple figures. A simple pattern of this kind decorates the upper part of each face of the Momine Khatun mausoleum. It is composed of identical hexagons drawing on a fine isogonal grid. This constructing technique was already known in the 10th century.

The pattern above the entrance to the Yusif ibn Kuseyir mausoleum is also built on a fine isogonal grid. Its foreground bands close in regular hexagons, and the background bands outline six-pointed stars.

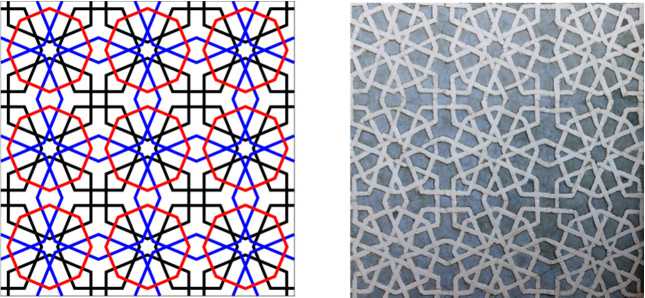

To construct the following pattern, an eight-pointed star with a 45° angle at its vertices is placed in the center of a square cell. The lines of the star's contour are extended outward, forming a macramé structure. The eight-pointed star is surrounded by an octagon, completing the construction of the cell.

All the lines of this pattern are closed, covering three figures: a small octagon (shown in red), a hexagonal barrel (black) and a large octagon (blue).

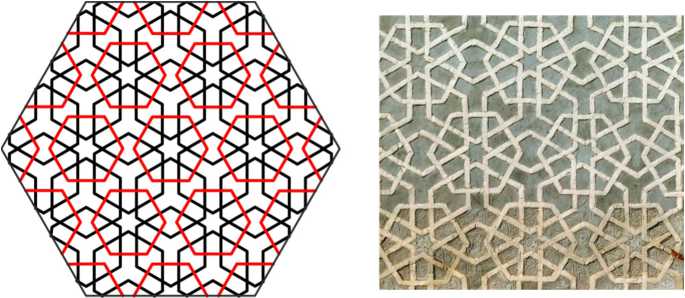

The following pattern from the Yusif ibn Kuseyir mausoleum is obtained by overlapping two types of regular hexagons. Black hexagons form quasi-macramé grid supported by small six-pointed stars; red hexagons encircle these stars, emphasizing the design.

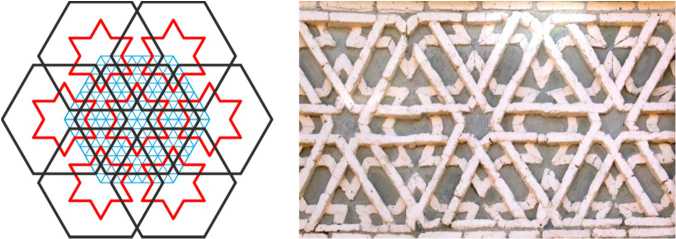

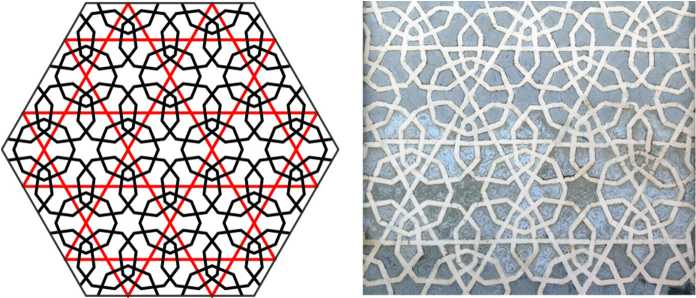

The next pattern is very original. It is based on a grid of lines dividing the plane into regular hexagons and equilateral triangles (shown in red), so that large six-pointed stars appear. Regular octagons are superimposed on this grid so that their diameters are deployed along the axes of symmetry of the grid. Sixes of octagons form six-pointed stars inside each hexagon.

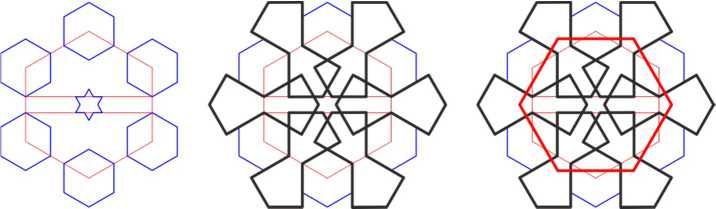

To construct the following pattern, place six hexagons at the vertices of a hexagonal cell and a six-pointed star in the center of this cell. Outline six bows (shown in black) and draw large hexagons (shown in red).

In the Nakhchivan mausoleums, this pattern is reproduced twice, both times on the tympanum of the mausoleum above the entrance. It seems that Ajami, for some reason, singled out this pattern from others, placing it in such a significant place. However, this pattern was not his invention: it is also known from the materials of the excavations of the palace in Ghazni, dating back to the 12th century.

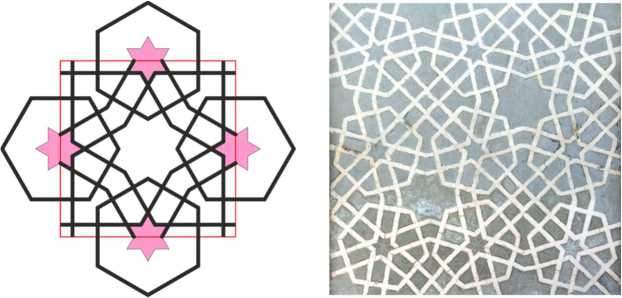

The last pattern in this group stands apart from the other patterns. It is built on a square grid, and its base is formed by regular octagons placed in the nods of this grid.

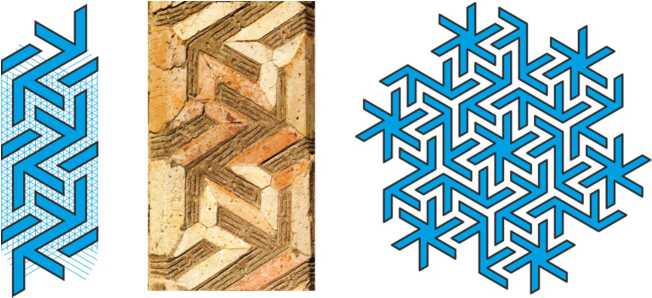

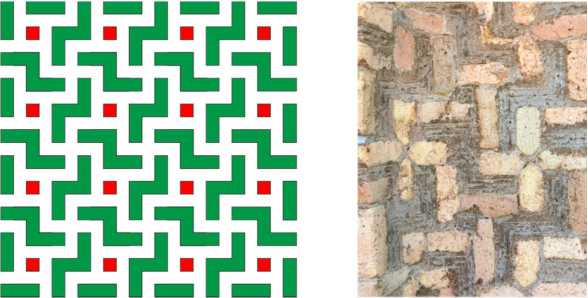

Patterns with vortex structures

The first pattern with vortex structures decorates both mausoleums. It is built on a fine square grid. Such patterns have two families of the 4th order symmetry centers. The centers of the first family are in the centers of small squares, and the centers of the second family are in the centers of swastikas.

The second pattern is also built on a fine square grid. In the Momine Khatun mausoleum it is represented by a meander strip; we can expand it to the entire plane. And again, there are two families of the 4th order symmetry centers, in the centers of small squares and in the centers of swastikas.

The third pattern, built on a fine isogonal grid, is also represented by a meander strip in the Momine Khatun mausoleum. Its figures are elements of a more complex pattern with six-pointed snowflakes.