“Gold-Boiling” Mangazeya — A Legendary City of the Russian Arctic

Автор: Lobanov K.V., Chicherov M.V.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Reviews and reports

Статья в выпуске: 59, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

For centuries, the Russians have been persistently developing the northern territories, moving further and further eastwards both by land and by sailing across the northern seas. The main goal of these journeys was furs, the trade of which brought huge profits to both industrialists and the state, being the main export item. Gradually, as reserves were depleted, the center of production shifted to the north and east, where enterprising industrialists actively penetrated, followed by the sovereign’s people, who taxed local tribes. At the end of the 16th century, the state, represented by Tsar Boris Godunov, realized the need to establish control over the territories beyond the Ob River, which were called Mangazeya, where Pomor merchants and industrialists were uncontrollably extracting furs. For this purpose, by Godunov’s decree of 1600, the city of Mangazeya was founded on the Taz River, which for several decades became the main stronghold and capital of the vast Mangazeya district. A huge flow of “soft gold” passed through the city, bringing income to the treasury and enriching enterprising people. From Mangazeya, detachments of industrialists and Cossacks went further east, to the Yenisei and Lena rivers, founding new strongholds, securing Siberian lands for the Russian state. The wealth of the northern territories attracted the interest of foreign invaders, who planned to seize these lands under various pretexts, taking advantage of the weakening of the Russian state during the Time of Troubles.

Mangazeya, fur trade, Siberia, polar navigation, Russian pioneers, Time of Troubles

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148331097

IDR: 148331097 | УДК: 902.6(571.1)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2025.59.249

Текст научной статьи “Gold-Boiling” Mangazeya — A Legendary City of the Russian Arctic

DOI:

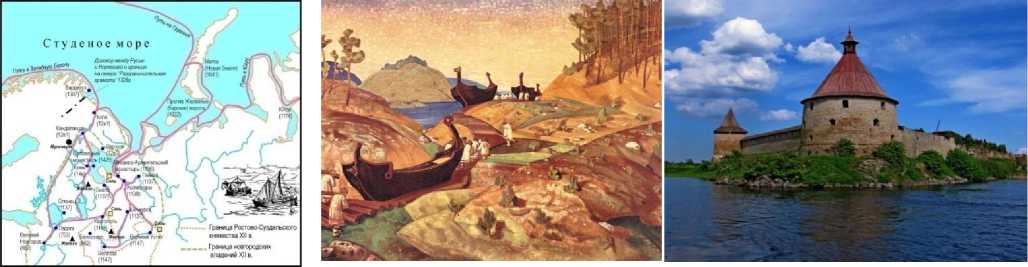

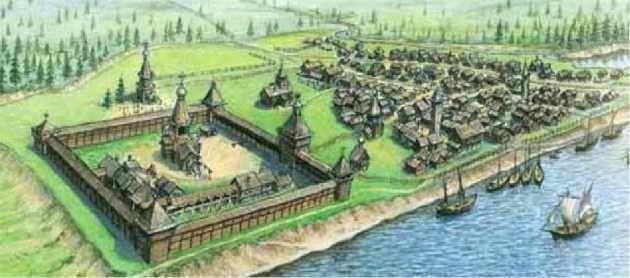

The Arctic zone became an integral part of the Old Russian state in the 9th century. The first Russian seafarers arrived on the coast of the Cold Sea in the 9th–12th centuries. The movement of Novgorodians into this zone began from the area of Ladoga (753), the first capital of the Russian state, and Novgorod (859). The first settlements appeared in the middle of the 11th century in the area of the Northern Dvina River, on the shores of the Onega Bay and the Kandalaksha Gulf. Merchants and industrialists went there to hunt furs, sea animals, and fish, spending there several months, and sometimes even years [1, Belov M.I.]. They moved along rivers and lakes on ships, and dragged them overland if they could not pass. Having collected the goods, the merchants returned to Novgorod, where they sold them (Fig. 1 a, b, c).

All these Novgorod volosts were called “Zavolochye”. From here, Novgorodians, and in later centuries — merchants of the Muscovite state, exported furs (sable, marten, beaver, ermine,

∗ © Lobanov K.V., Chicherov M.V., 2025

(a) (b) (c)

Fig. 1. The routes of Novgorodians to the North (a), “Volok”, artist N. Roerich (b), the first capital of Rus' — Ladoga (c).

As a result of the development of sea coastal voyages of Novgorodians from the mouth of the Northern Dvina westwards to the borders with Norway and eastwards to the Novaya Zemlya straits, previously isolated areas of the seas were connected. Druzhiny were regularly sent to the north to collect furs and to develop sea trades. These semi-industrial, semi-military groups settled temporarily and then permanently on the banks of rivers flowing into the seas. The local Karelian-Lopar and Nenets population submitted to the Novgorod power. In the 12th century, Novgorod forts and winter huts turned into cities on all trade routes in Pomorie and on the Kola Peninsula, as was indicated in Russian and Scandinavian chronicles [1, Belov M.I.].

Due to the harsh climate and low soil fertility, the main occupation of the newcomers was fishing, salt and fur hunting. They also mined bog iron ore, and river pearls were extracted on the northern rivers. The northern monasteries became important centers for the development of these territories: Mikhailo-Arkhangelskiy, Solovetskiy, Pechengskiy and others, which appeared here in the 12th–15th centuries.

The earliest written mention of the Novgorodians’ voyages to the northern seas can be found in the Novgorodskaya Sofiyskaya First Chronicle, which tells that the Novgorod posadnik Uleb went to the “Iron Gate” as early as 1032 [2]. Novgorodians penetrated into the Kara Sea in the first half of the 11th century. In 1147, Vologda was founded in the area where the waterways from Novgorod and the Volga crossed the Northern Dvina. In 1218, Velikiy Ustyug was founded on the Sukhona. In the treaty of 1264 between Novgorod and the Tver Prince Yaroslav Yaroslavovich, Vologda and Tre were also named as Novgorod’s subordinate regions in addition to Pechora, Yugra, Zavolochye. The territories to the west and east of the Northern Dvina were developed; in the 12th century, settlements were built on the banks of the rivers flowing into the Studenoe (White and Barents) Sea. The development of the Trans-Urals and Yugra began. In the 16th century, a sea route was laid to Western Europe and Siberia. The Pomors played a decisive role in the development of natural resources in the new territories of Siberia [3, Tsiporukha M.I.].

Sailing to the northwest, Novgorodians met the Norwegians, who disputed the Russians’ right to collect tribute from the local Karelian-Lopar population. Confrontations between them

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Konstantin V. Lobanov, Mikhail V. Chicherov. “Gold-Boiling” Mangazeya … continued for several centuries. In a persistent struggle, Novgorodians defended the Russian lands beyond the Arctic Circle and in 1326 concluded a treaty “Delimitation Charter” on the western border of the possessions [1, Belov M.I.]. The exact date of the foundation of Kola on the Murmansk coast is unknown, but it is first mentioned in the Norwegian chronicle in 1210, and in the Russian — in 1264. Since 1200, the Norwegians had to maintain a permanent naval guard to protect against the raids of Novgorod freebooters, and in 1307, they even built the fortress of Var-dehuz in the extreme north-east of Norway.

Seafaring to the west of the mouth of the Northern Dvina received new development after 1478, when the possessions of Novgorod, together with Pomorie, became part of the Muscovite state. In the same years, the sea route to Western Europe from the Northern Dvina was opened. Following the Russians, the Danes began to use it. The beginning of sea voyages from the Northern Dvina to the east was laid by the voyage of Novgorodians to the Iron (Kara) Gate [4, Okladnikov N.A.]. The first connections of Rus' with the Urals and Trans-Urals date back to the 7th–8th centuries, and these lands were called Yugra. In the 12th century, Novgorod imposed tribute on Yugra. The struggle for possession of this territory, rich in sable and other fur animals, continued for a long time. By the beginning of the 16th century, a sea route had been laid along the sea coasts, connecting the mouths of the Kola, Onega, Northern Dvina, Pechora, and Ob Rivers [5, Lobanov K.V.].

Novgorod colonization of the northern lands played an exceptionally important role in the economic development of the White and Barents Sea coasts, in the development of shipbuilding and navigation in the region. At first, this region was called Zavolochye, and from the 16th century, the name Pomorie was established for it. From the 12th century, Kholmogory became its center (1138).

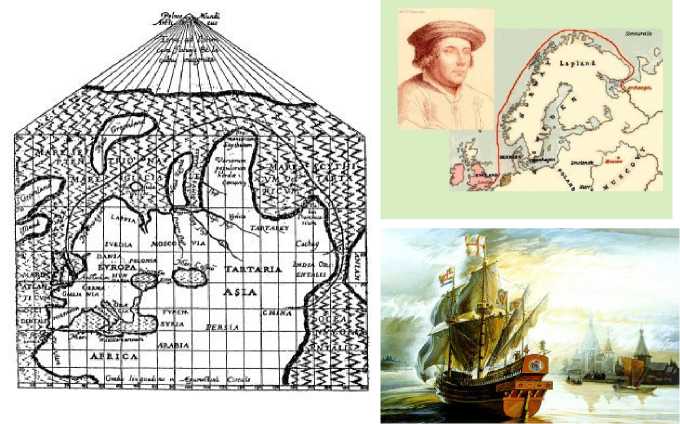

Search for the North-Eastern passage in the Studenoe Sea

As northern navigation developed, the route from the White Sea to Western Europe began to be explored. In 1492, a caravan of ships with grain departed from Kholmogory by sea for sale in European markets. In 1525, Dmitriy Gerasimov, the clerk of Grand Duke Vasiliy III, made a sea voyage from the Northern Dvina to Western Europe. In Rome, in a conversation with cartographer Paolo Giovio, he suggested the possibility of a sea route from Europe to China (Fig. 2a). “The Dvina, carrying away countless rivers, rushes in a swift current to the North... the sea there has such a huge extent that, according to a very probable assumption, keeping to the right bank, from there one can reach the country of China by ship, if no land is encountered in the interval” [6, Herberstein S.].

-

D. Gerasimov’s project was published in Rome in 1525 and was accepted with great interest by European countries, especially England, Holland and Denmark, since the southern routes were controlled by Spain and Portugal at that time [1, Belov M.I.]. In the 16th–17th centuries, European navigators made several voyages to the north, trying to find a sea route to the east.

Fig. 2. The North-Eastern route to The route of the English expe-

China (1611) (a) [7, Alekseev M.P.]. dition, R. Chancellor’s ship (b).

Reception of R. Chancellor by Ivan the Terrible in Moscow (c) (Illustrated Chronicle).

In 1553, the first English expedition was organized to search for the North-Eastern sea passage to China, led by H. Willoughby and R. Chancellor (Fig. 2 b, c). The English first set foot on Russian land on August 24, 1553. The ship “Edward Bonaventure”, captained by Richard Chancellor, entered the mouth of the Northern Dvina and moored near the Nikolo-Korelskiy Monastery, 35 km from Arkhangelsk. From there, Chancellor went to Kholmogory, and then to Moscow, where he gave Ivan the Terrible a letter from King Edward IV. From that moment, the Tsar allowed the English to trade in Russia. In 1555, they opened their office in the capital — the English Court. At the same time, it turned into the Moscow Company.

English factories appeared in Kholmogory, Vologda and Moscow. In 1569, the company received maximum rights: duty-free trade throughout the Muscovite state; trade with the Middle East through Russia; opening of iron and rope factories in the country; circulation of English coins in Moscow, Novgorod and Pskov. The English actively exported flax, hemp, ropes, resin, tar, lard, mast wood, furs, wax, honey, skins, leather, potash, oil and caviar from the Russian North. Ivan the Terrible wanted to turn England into his strategic partner, which is why he was so hospitable. With the beginning of the Livonian War, the ships of the Moscow Company supplied saltpeter, sulfur, lead, and tin to Russia. English engineers and doctors arrived in the country on them.

After the Livonian War, other foreigners also received permission to trade in the north of Russia. But the English could no longer freely cross Russian territory on their way to Persia and China. Nevertheless, the Moscow Company had the right to broad duty-free trade until the middle of the 17th century.

In 1556, the voyage of Stephen Barrow took place; he was the first foreigner to see Novaya Zemlya. In 1564, the Dane Dietmar Blefken sailed to Novaya Zemlya to find a passage to China, and in 1580, the English expedition of Pet and Jackman took place. In 1594, three Dutch expeditions led by J. Rijp, J. Gemskerk, Nye, Totgales and Willem Barents set out to find this route. In

1608, the English expedition of Hudson reached Novaya Zemlya, and in 1620, the Danish merchants Clement Bloom and Marleduk tried to reach the Novaya Zemlya straits, but were detained by the Kola authorities. In 1668, the expeditions of the Dutchman Willem Fleming and in 1676, the English captain John Wood reached Novaya Zemlya.

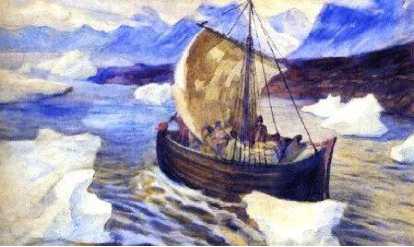

All European expeditions encountered insurmountable difficulties when sailing in the Stu-denoe Sea and could not go further than Novaya Zemlya due to the lack of experience and suitable vessels for such expeditions (Fig. 3 a). At the same time, the Pomors made regular voyages along the northern coast and went fishing on the Arctic islands. Over the long period of sailing in the Arctic zone, the Pomors created vessels that were best suited for travel in the northern seas and were known under the general name of “Koch”. These were single-deck sail-and-oar vessels with one mast, on which there was one sail (Fig. 3 b).

Artist I. Meshalkin “Koch in the ice” (b).

Fig. 3. English ships in the ice (a), engraving of 1876.

A characteristic design feature of the kochs was the spoon-shaped hull and reinforced double plating of the sides, which allowed them to move confidently among floating ice and gave the ability to be squeezed to the surface in case of strong ice compression. Relatively small kochs with a lifting capacity of 500-700 poods were used for navigation in the Arctic zone. Kochs with a displacement of 20 to 50 tons were built for sea voyages. The small draught of these vessels made it possible to move along the shallow waters along the coast, where there was no heavy ice, and their small dimensions and weight made it possible to pass along rivers and portages, thereby shortening the route and bypassing places with heavy ice conditions. The use of kochs allowed the Pomors to penetrate into areas inaccessible to European sailors on larger vessels.

Kochs were built in different sizes. Small vessels were used for coastal voyages. Larger ships were used to sail to Novaya Zemlya, Grumant (Spitsbergen), and to develop the coast of Siberia. For several centuries, kochs became a universal tool, with the help of which Russian people managed to conquer vast areas of Siberia and the Far East and the Arctic seas washing them [8, Lobanov K.V.].

Furs — oil and gas of medieval Rus'

The fur trade in Rus' has a long history. Due to the geographical features and climate, the central and northern regions of the Russian Plain were the habitat of fur animals. Since ancient times, the peoples living on the lands of the central and northern parts of the Russian Plain were engaged in the extraction of fur animals and supplied furs to the countries of southern Europe. Furs were an integral part of the trade of the Slavic peoples with Byzantium, which was carried out along the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks. Furs also played a major role in the trade of the ancient Russian principalities (Kyiv, Novgorod, etc.), being the basis of their prosperity. For a long time, Novgorod’s trade competitor was the Volga city of Bulgar, from where furs were also exported: marten, sable, squirrel, ermine, fox, beaver, hare. It should be noted that at that time, furs were practically the only material for making warm clothes for all strata of the population.

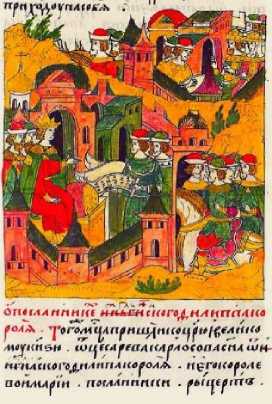

Furs were considered a valuable gift on par with precious metals and stones. The Radziwiłł Chronicle describes the meeting of Prince Igor with the Byzantine ambassadors in 945 as follows: “Igor, having confirmed peace with the Greeks, sent the ambassadors away, having gifted them with furs, servants, and wax, and let them go...” (Fig. 4) 1. When Yaroslav the Wise’s daughter Anna was married to the French King Henry I in the mid-11th century, her father-in-law not only dressed the entire foreign delegation in furs, but also sent his son-in-law several cartloads of “soft junk” as a dowry. Princess Olga promised the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrog-enitus gifts — “servants, wax and fur”, which she herself delivered to Constantinople in 957. Furs were also used to pay tribute by the subject peoples.

Fig. 4. Tribute in furs [9].

Fig. 5. Processing of furs (according to Olaus Magnus). Ring “bunts”, skin “kozki” and stitching of separate skins into large cloths can be seen.

After the Mongol conquest, when both Bulgar and Kiev fell into decline, the hunting grounds in the territories of western Rus' came under the control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Moscow was just beginning to gather Russian lands around itself, and Novgorod at that time effectively monopolized the export of furs. Taking advantage of its extensive trade relations with the cities of the Hanseatic League, Novgorod supplied large quantities of furs to the markets of Western Europe (Fig. 6). Thus, in 1405, three ships belonging to 107 Riga and Dorpat merchants arrived from Riga to Bruges. They brought 450 thousand skins, valued at 3,300 pounds groats. There are no documentary data on the total volume of fur exports from Novgorod, but based on the turnover of the largest merchants, the total amount of furs can be estimated at 500,000 pieces. At the same time, the number of processed skins and products made from them was small, since European merchants insisted on selling raw furs. Such trade policy restrained the development of fur- rier craft in Novgorod.

Furs were brought to procurement points scattered throughout the territory of the Novgorod Republic by means of willow rods tied into special ring-shaped “bunts”. These furs arrived in

Novgorod already packed in special “kozki” bags made from a whole skin removed like a stocking and opening at the top and bottom (Fig. 5, 6 b). In such bags, the skins, packed very tightly, almost did not rub against each other and did not lose their marketable condition. Already in Novgorod, the Hanseatic merchants packed furs into large wooden barrels for sea transportation and sent them to Germany and Flanders. A barrel contained from 5 to 7 thousand skins (small squirrel skins — up to 12 thousand).

Depending on the type, furs were sold in different lots: sable, ermine, marten, polecat — in forties, squirrel — in forties and thousands of skins. Counting furs in forties was also convenient because forty full sable or marten skins were used for a caftan (fur coat). Sables and martens were sometimes brought in pairs, especially as gifts, on the basis that two skins would be needed for a hat. Small squirrel pelts were often sewn into large cloths, which were then cut as ordinary fabric.

(a)

Fig. 6. Novgorod Republic of the 14th century (a); Yaroslav’s fur market (b).

Furs occupied the main place in the foreign trade of the Russian state in the 14th–17th cen-

(b)

turies. Only furs and wax were significant export items from Rus'. Other goods were significantly inferior to them both in physical volume and in value. Imported goods were practically not produced in the Russian lands. First of all, these were various metals, especially non-ferrous and precious [9, Khoroshkevich A.L.]. These metals were expensive: if Russian iron cost 60 kopecks per pood, then Swedish iron cost 1 ruble 30 kopecks per pood, and iron wire cost 1–3 rubles per pood. Non-ferrous metals were more expensive: copper — 1.5–3 rubles per pood, roofing copper — up to 6 rubles per pood, tin — 5 rubles per pood, silver — 450 rubles per pood, gold — 3,300 rubles per pood.

In fact, in the Middle Ages, furs played the same role for Russian principalities as oil and gas play in the modern Russian economy, providing the necessary funds for purchasing essential goods in Europe. The majority of furs exported were inexpensive squirrel fur (90%), which was in great demand in Europe, another 5% was marten fur, and other furs made up the remaining 5% [9, Khoroshkevich A.L.]. The bulk of squirrel furs were supplied to the market by feudal lords, who received them from their peasants as a tribute. For hunters, its extraction was even unprofitable. At the same time, the price of this fur increased significantly when it was resold to the West. Thus, in the north of Rus', a squirrel pelt cost half a kopeck, but in trade with Europe, a thousand squirrel skins cost 40 thalers (or “efimki”, as the Russians called the main silver coin of Europe at that time), that is, a kilogram of silver [10, Vilkov O.N.].

Expensive furs, primarily sable, were obtained in the vast northern lands of Velikiy Novgorod, extending beyond the northern Urals (Fig. 6 a). The Yugra tribes subordinate to Novgorod paid yasak in furs. However, it should be noted that Novgorod’s control over these lands was rather conditional. The tribes periodically refused to pay tribute, and then it was necessary to organize new military campaigns to conquer them [11, Nikitin D.N.].

Starting from the 14th century, the Moscow principality began to extend its influence to the lands of Pechora, Mezen, and others, gradually displacing Novgorod and collecting tribute from the local population [12]. In addition to the Moscow princes, other Russian princes actively sought to penetrate these territories: Rostov, Yaroslavl, Beloozersk. The situation began to change after Ivan III annexed Novgorod along with all its possessions to the Moscow principality in 1478. As a result of two military campaigns, the united Russian state managed to conquer these lands.

During the second campaign in 1499, the first Russian city beyond the Arctic Circle, Pustozersk, was built at the mouth of the Pechora. Subsequently, this city served as an important stronghold for the development and control of the northern territories. After this, intensive development of these lands began. Merchants, industrialists and Cossacks actively penetrated this region, establishing exchange trade and collecting yasak.

The origins of Mangazeya

Boris Godunov (Fig. 7a) sent the first expedition led by Prince Shakhovskiy to the north of Western Siberia in 1600 to search for places rich in furs. There was a very high demand for furs in many European countries, and he wanted to put this trade under state control. The Samoyeds here were hired by Russian hunters and did not want to pay taxes to the treasury, as they realised that the appearance of sovereign’s people in these places would put an end to the freedom.

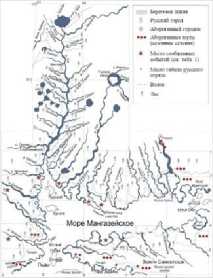

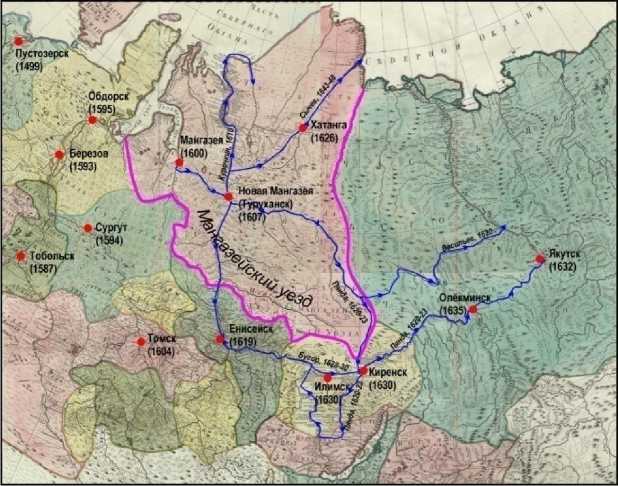

Due to the danger of penetration of European expeditions from England, Holland, Denmark and other countries beyond the Urals into the lower reaches of the Ob and Yenisei rivers, the following ostrogi (forts) were founded on the orders of Boris Godunov: Berezov (1593), Surgut (1594), Obdorsk (1595), Nadym (1598), Mangazeya (1600), which were supposed to protect these lands from colonial seizure by foreigners (Fig. 7 b).

The advancement of Russian people into this region was carried out along several routes. Two routes followed the northern rivers, through the Ural Mountains into the Ob basin and out to Berezov. The southern route ran through Verkhoturye to Tobolsk, from which they went on kochs to Mangazeya. This route was difficult and long. The voyage from Tobolsk to Mangazeya alone could take up to thirteen weeks. It took even longer to get from Pomorie to Tobolsk (Fig. 7 c) [13,

Belov M.I.].

The fastest was the sea route, the so-called Mangazeya route. The first expeditions from Kholmogory and Pinega to the Ob are mentioned in the chronicles at the beginning of the 16th century (1517). In the second half of the 16th century, they became regular. The route began at the mouth of the Northern Dvina and Mezen. Then there was a portage across the Kanin Peninsula and then along the coast, through the strait between Vaygach Island and the mainland, to Baydaratskaya Bay to the Sharapovy Koshki Islands. Then the movement went up the Mutnaya River to a portage to the Zelenaya River, along which they descended directly into the Ob Bay, then they entered the Tazovskaya Bay and moved up the Taz River to Mangazeya (Fig. 7 c). Under favorable conditions, the entire journey took five to six weeks.

-

(a) (b) (c)

Fig. 7. Tsar Boris Godunov (1598-1605) (a), fortified towns in the lower reaches of the Ob (b), river and sea routes to Mangazeya and a portage across the Yamal Peninsula (c) [13, Belov M.I.].

In 1601, a larger detachment of two hundred service people led by voivodes Vasiliy Mosal-skiy and Savluk Pushkin was sent to help Shakhovskiy. They helped to complete the construction of a wooden fort and to establish a trading post. It should be noted that from the very beginning, two voivodes were appointed to Mangazeya, as to other Siberian cities, and this circumstance subsequently played a negative role in the history of the city.

The foundation and construction of Mangazeya fell on a very difficult time in the history of Russia. From 1601 to 1603, the country suffered from severe crop failure and the resulting mass famine. It is believed that these hardships were caused by a major geological catastrophe — a powerful eruption of the Huaynaputina volcano in Peru in South America in February 1600, which ejected about 30 km3 of ash into the Earth’s atmosphere to a height of 35 km. The ash, dispersed by air currents in the atmosphere, sharply reduced the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth’s surface. As a result, summer temperatures dropped sharply, causing massive crop failures. The most catastrophic consequences were in Russia, where up to 2 million people died of hunger (out of a total population of 6 million). The discontent of the people led to the weakening of state power and launched a series of events that led to the Time of Troubles and brought the Russian state itself to the brink of destruction [14, Lobanov K.V.].

Mangazeya voivode Davyd Zherebtsov — a hero of the Time of Troubles

Everyone knows well the heroes of the Time of Troubles — Dmitry Pozharskiy, Kuzma Minin, Avraamiy (Palitsyn), but another hero of this time is little known — Mangazeya voivode Davyd Zherebtsov. Under Boris Godunov, he served as an elected nobleman in Rzhev and was appointed bailiff to the disgraced Romanovs, exiled to their patrimonial village of Kliny in the Yuryev-skiy district. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why his name, like many other prominent figures of the Russian resistance during the Great Troubles, was carefully erased from the history of the country during the reign of the Romanov dynasty. The royalty did not want anyone else to stand next to them in the history of the formation of the Russian state.

In 1606, the new Tsar Vasiliy IV Shuiskiy sent Zherebtsov as a voivode to distant Man-gazeya. He was confident in his good organizational skills and that he would be able to build a strategically important ostrog on the north-eastern borders. Zherebtsov was sent from Moscow as a close associate of Boris Godunov. By the way, some historians are sure that Godunov was actually poisoned by the boyars, and precisely with the active participation of Vasiliy IV Shuiskiy.

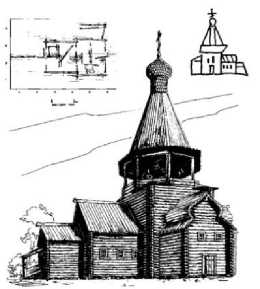

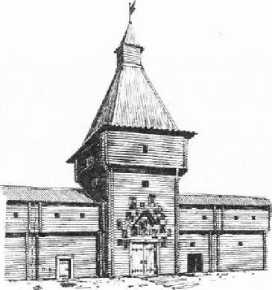

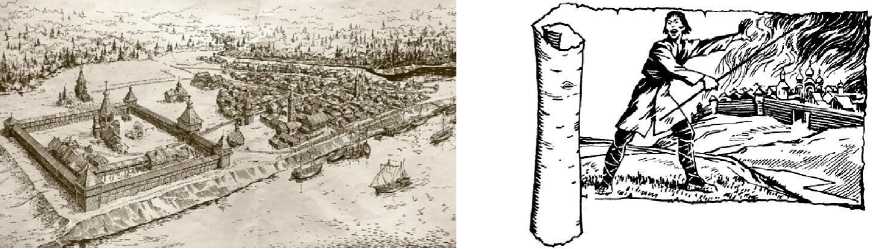

In 1607, Zherebtsov and Davydov began to build log walls from log cages on the site of the ostrog. As a result, a powerful fortress by northern standards, equipped with artillery, appeared in Mangazeya. It had a classic appearance for that time. It had five towers (four at the corners and one over the gate), and the height of the walls ranged from 1.5 to 4.5 sazhens. The fortress itself housed the residences of both voivodes, a temple, an assembly house, a customs house, and other administrative and utility buildings. There was also a so-called amanat house, a purely Siberian phenomenon. In such houses, hostages from among the local nobility were kept, so that the local population would regularly pay yasak. A garrison of up to 100 riflemen was permanently stationed in Mangazeya, who were engaged in collecting yasak. Outside the fortress there was a settlement. In total, there were up to 500 different buildings (Fig. 8). Churches, barns, shops, craft workshops, and residential buildings were built. The total population of Mangazeya reached 2,000 people. It was the largest city beyond the Arctic Circle.

(a) (b)

Fig. 8. Mangazeya (reconstruction by M.I. Belov) (a); The Mangazeya Sea. A drawing from the Chorographic Drawing Book by S. Remezov (b).

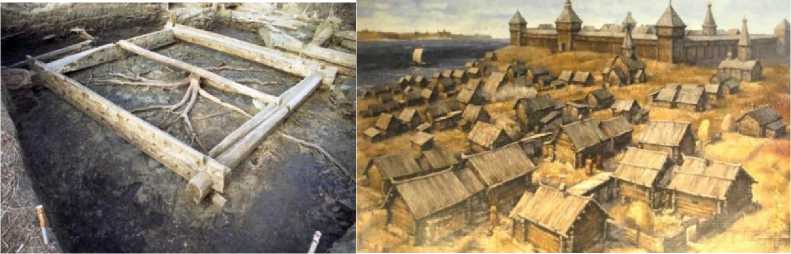

For the first time, special technologies were developed and used for building houses in

Mangazeya, as this region is located in the permafrost zone. Houses were built on a layer of frozen wood chips, covered with a layer of birch bark for waterproofing, so that groundwater would not wash away the foundation. Often, to prevent the house from “twisting”, the log frame was installed on the root system of a cut tree — so that the stump was in the middle of the house, and the walls of the log frame were on the roots (Fig. 9) [15, Vizgalov G.P.].

Fig. 9. Construction of a house on the tree root system (photo by SPA “Northern Archeology-1”). It can be seen that pieces of ship keel were used in construction; Mangazeya (reconstruction).

In 1627, in the period of the city’s prosperity, up to 700 industrialists spent the winter here. At the same time, the Tobolsk voivodes demanded from the officials in Mangazeya to treat the local population more kindly, not to commit arbitrary rule and excessive taxation, and to restrain the Cossacks from robberies and violence against the local Mangazeya Samoyeds.

The new fortress became the economic center of Siberia. In 1608, yasak was regularly delivered to Mangazeya not only by local tribes — Samoyeds (Nenets) and Ostyak-Samoyeds (Selkups), but also by the Yenisei Ostyaks (Kets) and Tungus (Evenks) living much further south. In 1607, during a campaign to the east, the detachment of Davyd Zherebtsov and Kurdyuk Davydov founded a winter hut on the Yenisei in the delta of the Turukhan River, on the site of which New Mangazeya (Turukhansk) would later grow. But Zherebtsov would never see this, since the “Siberian epic” of the voivode would be interrupted by a call for help from Tsar Vasiliy IV Shuiskiy, which came from Moscow, besieged by the troops of False Dmitriy II.

In distant Mangazeya, the voivode Davyd Zherebtsov received news of the siege of Moscow. In the winter of 1608-1609, a large detachment of 1,200 Siberian riflemen under his command made an incredible “ice march” from Mangazeya to Central Russia. There they were joined by 600 Arkhangelsk riflemen, and then — by detachments from Nizhniy Novgorod and Kostroma. Unexpectedly for the Tushino people of “False Dmitriy II”, who had already taken control of most of the country, these powerful forces appeared at the walls of the Ipatyevo-Troitskiy Monastery in Kostroma. The capture of Kostroma by Zherebtsov’s army on May 1, 1609 coincided with the departure of the troops of the young prince Mikhail Skopin-Shuiskiy and the allied Swedes from Velikiy Novgorod (Fig. 10). In June, near Kostroma, Zherebtsov defeated the troops of the Zapo-rozhian and Don Cossacks led by the Lithuanian nobleman Lisovskiy.

After that, Zherebtsov led his army to Kalyazin, where Mikhail Skopin-Shuiskiy was forming an army for a campaign to Moscow. By that time, the people had accumulated hatred for the “Tushino thief”, who was giving away Russian lands to Polish-Lithuanian invaders. People flocked to Kalyazin from all parts of the country, ready to fight the invaders. The detachments of the Sibe- rian voivode significantly strengthened the army of Skopin-Shuiskiy. They liberated the Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda, Pereyaslavl-Zalesskiy, and Dmitrov. When False Dmitry II’s associate Hetman Jan Sapieha learnt about it, he withdrew most of his army from the siege of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery (Fig. 11), the defenders of which by that time were on the verge of exhaustion of military and physical forces, and moved his army to Kalyazin.

From the moment he joined forces with Skopin-Shuiskiy, Davyd Zherebtsov carried out the most important assignments. At first, he was sent to Rostov the Great for reconnaissance purposes. As noted by an eyewitness, “and now Prince Mikhail Vasilyevich is stationed in the Kalyazin Monastery, and he sent the voivode Davyd Zherebtsov to the Borisoglebskiy Monastery and to Rostov”. Upon returning to Kalyazin, Zherebtsov took part in the decisive battle with the Sapezhi- ans.

Fig. 10. Prince M.V. Skopin-Shuiskiy, leader of the militia in 1609-1610.

Fig. 11. Defense of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, artist S.D. Magidovich.

During the night of October 19–20, 1609, the vanguard units of Skopin-Shuiskiy’s army approached the Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda near the Trinity-Sergius Monastery and attacked the “Sa-pezhin” garrison. As soon as Hetman Sapieha came out from under the walls of the monastery to help his garrison in the direction of the Aleksandrovskaya Sloboda, pre-selected units led by the voivode Zherebtsov easily crushed the guards and broke into the besieged monastery. This “special forces” detachment numbered about 1,000 experienced Siberian riflemen. Having made a brilliant breakthrough into the monastery, Davyd Zherebtsov, despite the dissatisfaction of the local voivodes, assumed further command of the defense of the monastery of St. Sergius of Radonezh. In 1610, Davyd Zherebtsov died heroically during the defense of the Trinity Makaryev Monastery in Kalyazin from the Poles 2.

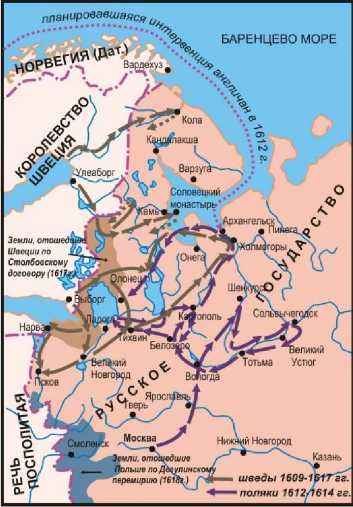

Plans to seize the Russian north during the Time of Troubles

During the siege of Moscow and after its liberation, Polish detachments rushed north to Pomorie, since there were no Russian troops there. They captured and plundered the cities of Belozersk, Vologda, Soligalich, and attacked Kargopol (Fig. 12 a). The Poles besieged Kholmogory, but without taking the city, some of the troops went to plunder Vaga, while others ravaged the

Byakontov.

URL:

Nikolo-Korelskiy Monastery, the suburbs of Arkhangelsk, Nenoksa, and Luda (Fig. 12 b) [16, Melnikova A.S.].

The Swedes considered Velikiy Novgorod their military prey and a springboard for the development and capture of the entire North-West of Russia, as False Dmitry had promised them. They demanded to get the original Russian lands — Pskov, Gdov, Izhora, southern Priladozhye, Kola and the entire Kola Peninsula, Sumy and the Solovetskiy Monastery, Northern Karelia, Arkhan- gelsk, Kholmogory (Fig. 12 c).

During these years, the English wanted to seize the Russian North and take control over the

Volga route to the Caspian. In 1609, Thomas Chamberlain presented to the king a project for Eng- lish intervention in Russia. The English offered the Russian government assistance with armed forces. In June 1612, ships with English troops arrived in Arkhangelsk. Their representative, J. Shav, went to the camp of Prince D. M. Pozharskiy in Yaroslavl to negotiate the terms of military assis- tance, but the militia leaders resolutely refused it.

(a)

Fig. 12. Invasion of Polish and Swedish troops into the territory of the Russian state; (b) Polish troops, (c) Swedish

(b)

(c)

troops.

The secret project of Polish-Spanish colonization of Arkhangelsk and adjacent lands became public in the winter of 1610–1611. The Swedish king was ready to take part in it if the Moscow boyars refused to pay him the debt of Tsar Vasiliy Shuiskiy. In January 1611, Charles IX addressed a message to the abbot of the Solovetskiy Monastery warning about Polish intrigues. False Dmitry II was informed about this. The king offered him an alliance against the Poles if the debts were paid [17, Forsten G.V.]. He frightened the “Muscovites” with the invasion of the Spanish king into the Russian North in the interests of the Poles and offered the boyars help against the Poles if they “properly” paid all debts to him (Fig. 12 a) [18, Widekind J.].

The intention of Sigismund III to attract the Spanish fleet to colonize the northern territories of Muscovy took this plan to a new level of danger. The project of a Polish-Spanish invasion of the Russian North was known not only in Sweden, but also in England. In 1611, Sigismund III turned to King James I, asking him to confirm that English merchants would not interfere in the political events taking place in Muscovy, and in the event of their escalation would not help the Russians with mercenaries and military goods [19, Taimasova L.Yu.]. Fears that London would choose the side of the Polish king forced the Moscow authorities to pay generously to the English “guests”.

Under Ivan the Terrible, agents of the Moscow Company in Russia provided the English court with military and economic intelligence services: they recruited Russian merchants and officials, bribed and blackmailed them (Fig. 13 a).

In 1914, St. Petersburg archivist Inna Lyubimenko, an expert on Russian-British trade relations at the turn of the 16th–17th centuries, while working in the English special repository, discovered strange materials and almost immediately realized that she was holding a real historical “bomb” in her hands. She wrote the article “The English Project of 1612 on the Subordination of the Russian North to the Protectorate of King James I” and published it [20, Lyubimenko I.; 21, Lyubimenko I.I.].

The first document was a copy of a letter addressed to the Privy Council at the court of King Charles I. The English captain Chamberlain, who in 1610–1613 took part in some extremely secret mission, reported: “On my return from Russia, I presented to King James I of late memory the entire Russian state, the annual crown income of which amounts to 8 million pounds sterling. Sir John Merrick and Sir William Russell were sent to the nobility of this nation... and proposed in the name of the King of Great Britain that His Majesty become their emperor and patron, to which, in general, they agreed with gratitude and sent their ambassador with a great gift to the king to enter into negotiations with him regarding this matter.”

The second document dealt with the negotiations themselves and was preceded by an assessment of Russian realities in the Time of Troubles. It spoke of territories that had not yet been affected by the war and had still “preserved their integrity”, and of those that were already “anticipating” the coming “horrors” and, “having heard of the glory of His Majesty, his great wisdom and kindness, prefer to surrender themselves into his hands than into any other”.

The head of the Moscow Company (Fig. 13 b), John Smith, played a leading role in these negotiations and managed to attract “authoritative British merchants”. The following quote helps to realize both the extent of English territorial claims and the hopes of English merchant diplomacy: “If His Majesty were to receive an offer of sovereignty of that part of Muscovy which lies between Arkhangelsk and the Volga, and of the waterway along that river to the Caspian or Persian Sea, or at least a protectorate over it and complete freedom for English trade, it would be the happiest offer ever made to our state since Columbus offered Henry VII the West Indies for him…”

Knowing the paucity of the British treasury, the author makes an ingenious proposal — to place the financial burden of bringing the Russian North under the hand of the monarch of England on... the Russians. He even outlines a scheme of how it could be done. In May, the British fleet will leave England to conclude a treaty with the Russian population, and in the autumn, when it moves back, the Russians “are allowed to send their ambassadors with them to confirm the treaty”, “and in the meantime, let them prepare to put into the hands of the English company enough treasury and goods to pay for arming and transporting the number of troops they need”.

(a) (b) (c)

Fig. 13. The capture of the Russian North (a); the Moscow Company (b); John Merrick in Arkhangelsk (c).

From the middle of the 16th century, the main trade route of the British to Russia was the city of Arkhangelsk. From that period, British merchants took over a privileged position in the foreign trade of Muscovy. The courts of the London-Moscow Company operated in the largest and most successful cities — Moscow, Yaroslavl, Arkhangelsk, Vologda, Astrakhan, Kazan. British merchants were ready to support any new government that promised them the former stability. The goal was the same — control over the main trade transit through Russia. Following the proposal presented by John Merrick, an armed British unit of 150 soldiers landed in Arkhangelsk in the summer of 1612 (Fig. 13 c). There are records that the detachment arrived in Yaroslavl, where the militia commander Prince Pozharskiy was offered to jointly seize Moscow.

English archives have a draft dated 14 April 1613 by Julius Caesar, an influential Chancellor of the Exchequer in the time of James I. The draft stated that in the unaffected North, “the people are willing, and even forced by necessity, to surrender themselves into the hands of some sovereign who can protect them, and are willing to submit to the rule of a foreigner, seeing that none of their own sovereigns are left”. There is also a remark about “fortifying” the port of Arkhangelsk and whether “1,000 English soldiers” would be enough for this. In the summer of 1611, representatives of the northern Russian regions were already conducting negotiations with the English company agent Merrick [22, Labutina T.L.]

The authors of the project assured King James I that he had “sufficient grounds to take into his own hands the protection of this people and a protectorate over them on terms that can ensure and protect the freedom of trade that we are already conducting and will undertake in the future”. They requested that an authorized person be sent to the north to negotiate a treaty with the local population on terms of sovereignty or protectorate. Even before the Time of Troubles, the English had dreamed of laying transit through Russia “to Shemakha, Bukhara, Samarkand and China”. During the Time of Troubles, they wanted all of Russia. On behalf of their plenipotentiaries — John Smith and John Merrick — agents of the Moscow Trading Company, they were preparing for a veiled seizure of the Arkhangelsk and Vologda regions and practically the entire Volga region with access to the Caspian Sea.

Britain’s attempt to carry out a “soft occupation” of Russian territories failed. Russia coped with the Polish intervention. In February 1613, the first of the Romanov dynasty, Tsar Mikhail, took the throne of Muscovy. He ruled firmly, stopped disorder in the country and, thus, completely destroyed all the plans of the English. But even to this day, few people know that the history of the Russian State in the first decade of the 17th century could have been completely different, and that today we could well be not citizens of the Russian Federation, but subjects of the English crown.

By the beginning of the 17th century, the Kremlin authorities were well aware of the rich deposits of precious metals in the “land of Pisid” [19, Taimasova L.Yu.]. However, the remoteness and inaccessibility of those places made such knowledge useless for a long time. Tsar Vasiliy Shuiskiy was concerned about the issue of improving the monetary situation in Moscow and turned to the English for help. He returned all the privileges and liberties to the merchants of the Moscow Company [23, Bantysh-Kamenskiy N.N.]. Privately, through English “guests”, the tsar asked King James I to send a specialist in the purification of natural gold. It was assumed that the Moscow money court would produce Russian gold coins that would be as pure as European standards. To implement this project, the master Walter Busby arrived to the court of Tsar Vasiliy around 1608 with recommendations from James I [24, Kurlaev E.A.].

Moscow intended to transfer the mines of the “land of Pisid” to the merchants of the Moscow Company on the terms of a “concession”. Part of the mined gold was to go to the royal treasury as “concession” payments. However, for some reasons, the deal with the Moscow Company did not take place, and the English assayer was out of work. According to this additional plan, the territory of the Russian North, coming under the control of the English, stretched from the Kola Peninsula to the Urals and further to the Yenisei River and included all the richest lands of Siberia with furs, including the “gold-boiling Mangazeya”.

While the document was under consideration by King James, detachments of “volunteers” began to gather in England, ready to act on the side of the Muscovite Kingdom against the Polish invaders. In reality, they were trying to penetrate Arkhangelsk. On the advice of Prince Dmitriy Pozharskiy, the head of the people’s militia fighting the Poles on Russian territory, the English volunteers were not allowed into the North [23]. Meanwhile, in October 1612, the Polish invaders were expelled from Moscow, and in January 1613, Mikhail Romanov came to the throne.

The Russian state was quickly revived by the trade of Siberian furs, which were so persistently claimed by the British. The subsequent war with Poland, as a result of which Moscow returned Smolensk with Left-bank Ukraine, was conducted using the same money. At the height of military battles, hundreds of thousands of rubles were received from the export of Siberian furs to the West. Therefore, London’s dreams are understandable and had far-reaching plans. Since then, the English had repeatedly tried to take revenge, taking the Russian North into their hands. The next unsuccessful attempt was made in the Crimean War of 1854, but then the British fleet left “empty-handed”. The last clear case dates back to 1918, when, in the midst of the Civil War, the English had already seized upon the treasured northern riches, but, alas, again went home in disgrace.

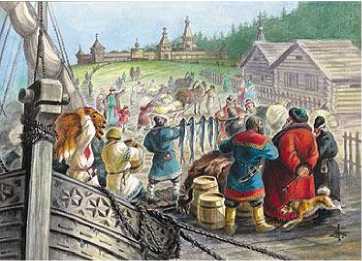

“Gold-boiling” Mangazeya

With the construction of Mangazeya, the sable trade began to develop rapidly, reaching its peak in the 1640s, when 145 thousand animals were hunted annually. At the end of the century, this figure fell to 42 thousand. In total, 7,248,000 sables were hunted in Siberia from 1621 to 1690. At the peak of fur production in the 1630s, 1 ruble invested in goods for exchange sometimes brought furs worth 32 rubles in one year [25, Belov M.I.]! It is not surprising that Mangazeya received the nickname “gold-boiling”. Thousands of people flocked here, disregarding the dangers, hoping to get rich quickly. Industrialists were followed by merchants who supplied the city with everything it needed (Fig. 14).

-

(a) (b) ©

Fig. 14. Trade in Mangazeya (a); Mangazeya. Trinity Cathedral Church (b) [25, Belov M.I.]; Spasskaya gatehouse of the Mangazeya ostrog (c) [26, Serikov I.A.].

The value of the sables was enormous. Thus, the customs book of 1636 shows 87,210 sables obtained, which, converted into money, amounted to a sum close to half a million rubles, which was equal to the entire annual income of the royal court in the 1670s. In total, according to the customs books for 1630-1637 (7 years), 477,469 sables worth 2,387,345 rubles passed through the Mangazeya customs. At the same time, the tithe tax from private industrialists gave the state treasury more furs than the yasak tax from the natives of the Mangazeya district (Fig. 14) [8, Lobanov K.V.].

Table 1

Cost of furs in the 17th century 3

|

Fur |

Cost |

|

Sable |

50 rubles/forty (from 14 to 600–800 rubles) |

|

Sable fur coat |

50 rubles |

|

Squirrel |

7–20 rubles per thousand |

|

Black fox silver-brown red and brown |

10–50 rubles per piece from 6 rubles per piece 50 kopecks per piece |

|

Marten |

10–20 rubles/forty |

|

Beaver |

Avg. 2 rubles/piece |

|

Ermin |

2–3 rubles/forty, separate skin 2–3 altyns |

|

Arctic fox |

4–5 altyns per piece |

|

Wolverine |

1–2 rubles per piece |

|

Wolf |

1 ruble per piece |

|

Hare |

25–30 kopecks per dozen |

(а) (b)

Fig. 14. Siberian sable (a), Yasak collection (b). Artist O.V. Fedorov.

In Moscow, sables were valued higher in duty than in Mangazeya. For example, in 1628 in Mangazeya the tithe tax of soft junk was valued at 15,354 rubles, and in Moscow — 17,285 rubles; in 1635, the tithe soft junk in Mangazeya was valued at 10,749 rubles, in Moscow — 12,952 rubles. Thus, if we add yasak and other taxes to the tithe tax, it turns out that the sovereign’s treasury annually received soft goods from Mangazeya ranging from 17,000 to 30,000 rubles at Moscow prices [28, Butsinsky P.N.].

Along with sables, which made up the bulk of furs in value terms, other fur animals were also hunted (Table 1) [27, Yanitskiy N.F.]. But the people of Mangazeya were engaged not only in fur hunting. Various crafts were actively developing in the city. Bone carving was widely developed, as evidenced by numerous finds of items made of mammoth bone and parts for future products [15, Vizgalov G.P.].

The sensation of Mangazeya was the foundry, where crucibles were discovered — ceramic pots for smelting copper ore. The analysis of copper residues found by N.N. Urvantsev showed

-

3 [27, Yanitskiy N.F.]

that they contained platinum and palladium, typical for secondary carbonate copper ores of Norilsk deposit. The Mangazeya people smelted the carbonate ore of the Norilsk deposit, where oxide ores came to the surface and were clearly visible due to their bright color and fusibility. The ore was transported 500 km from the Norilsk winter camp to Mangazeya in winter on reindeer sleds (Fig. 16 a).

Analysis of copper samples, conducted in the spectral laboratory of the Scientific Research Institute of Arctic Geology, showed the following:

-

• a fragment of copper product: Pt0.013 g/t; Pd0.08 g/t;

-

• a piece of copper sheet; Pt0.023 g/t; Pd0.13 g/t;

-

• slag: not detected.

Consequently, the Mangazeya people smelted the carbonate Norilsk ore. Carbonate ores are easily smelted and easily noticeable due to their bright green or blue color [25, Belov M.I.].

(a)

(b)

(c)

Fig. 16. Possible route for the delivery of copper ore to Mangazeya (a); azurite (b); metal products (c) found during excavations in Mangazeya; metal smelting crucible (d).

(d)

In Norilsk, at the foot of the mountain later called Rudnaya, a pack of clay shales impregnated with carbonate copper salts — minerals, malachite and azurite (Fig. 16 b) — came to the surface. These shales were seen in 1866 by F.B. Schmidt during his visit to Norilsk. Their bright green and blue colors immediately caught the eye, attracting the attention of anyone, even those not familiar with mining. Such carbonate ores easily melt in furnaces of the most primitive design, which is why people of that time could mine them. Obviously, these copper-carbonate ores were used by the artisans of Mangazeya (Fig. 16 c, d). The presence of platinoids in copper smelts and the remains of copper products found during excavations of the Mangazeya foundry confirm this

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Konstantin V. Lobanov, Mikhail V. Chicherov. “Gold-Boiling” Mangazeya … conclusion. These metals are typical for all Norilsk ores: both primary sulfurous and secondary copper-carbonate oxides [8, Lobanov K.V.].

The history of the development of copper ores in Taimyr has a very long history. In the area of the unique giant Cu-Ni-Pt Norilsk deposit, the so-called Pyasinskiy metallurgical center was located in ancient times. Products of the world’s northernmost Bronze Age masters were found here: anthropomorphic figures, remains of cult items, arrowheads, knife handles, etc. [29, Denisov V.V.]. According to the remains of birch bark, the time of activity of ancient metallurgists is estimated at 2800–3200 years ago. This indicates a climate at that time that was close to the modern climate of central Russia. The development of metallurgy in Taymyr in the Bronze Age was due to the region’s richness in copper ores and the presence of the Arylakh deposit, easily accessible for surface mining with abundance of large copper nuggets. On the northern cape of the Rudnaya Mount (Norilsk 1), chalcopyrite veins containing up to 20% copper and 5% nickel came to the surface [30, Starostin V.I.].

Campaigns of the Mangazeya people to the Yenisei and Lena

From Mangazeya, detachments of industrialists and Cossacks travelled further east, and due to the depletion of the resource base, they went in search of furs to the Yenisei and Lena. The

Turukhansk winter camp, founded by the Mangazeya people in 1607, played a key role (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Campaigns of the Mangazeya people to the east [31, Magidovich I.P.]. The map of Siberia and the borders of the Mangazeya district are shown according to the atlas of 1745 [32].

In 1610, Kondratiy Kurochkin made the first voyage to the mouth of the Yenisei, and then reached the Pyasina River across the open sea. He pointed out that it was possible to pass to the Yenisei by sea on large ships, which alarmed the authorities in Moscow. In 1620, a detachment of Demid Pyanda set out on a campaign to Lena. He came to Turukhansk from Mangazeya with a group of hunters. In 3.5 years, he traveled about 8,000 km along new river routes and began the discovery of Eastern Siberia by the Russians. He explored the Lower Tunguska for 2,300 km and proved that its upper reaches and the Lena converge, and through the portage he discovered, hunters began to penetrate the Lena. During one summer, Pyanda traveled about 4,000 km up and down the Lena and traced its course for 2,400 km. He showed the Russians a convenient route from the upper Lena to the Angara. Pyanda was the first Russian to trace the course of the Angara for almost 1,400 km from its source and proved that it and the Upper Tunguska were one and the same river. Stories about him were collected in the Yenisei region and Yakutia by the historian G. Miller, a member of the academic detachment of the Great Northern Expedition.

In 1630, Martyn Vasilyev and his detachment made a campaign along the northern route. He went along the Nizhnyaya Tunguska, Chona and Vilyuy rivers to the Lena. During the campaign of 1628–1630, Vasiliy Bugor discovered the southernmost route leading from the Yenisei basin to the Lena. He went with detachments up the right tributary of the Angara, the Ilim, and its tributary, the Igirma, where it converges with the Kuta, crossed the watershed to the Kuta, and went down it to the upper Lena. To collect yasak, Bugor left two posts on the upper Lena, on the sites of which the Kirensk and Ust-Kut forts were later built [8, Lobanov K.V.].

The Mangazeya people penetrated the sea coast to the east of Taimyr. In 1643, Vasiliy Sychov with a detachment from Turukhansk went to the upper Pyasina, and then to Kheta, he went down along it and the Khatanga to the bay and reached the middle reaches of the Anabar River. Thus, industrialists and service people from Mangazeya and Turukhansk developed the lands in the Yenisei basin, discovered Lake Baikal, a large part of the Lena basin, and traced almost its entire course from the upper reaches to the mouth [31, Magidovich I.P.].

The decline of Mangazeya

Despite the importance of Mangazeya, which allowed controlling vast, sparsely populated northern territories rich in furs, the city’s life was short. Both objective and subjective factors played a role in this.

The enormous wealth passing through Mangazeya could not fail to attract the interest of the Tobolsk voivodes. The Tobolsk voivode, Prince Ivan Kurakin (1616–1620), urged Tsar Mikhail Romanov to forbid the Mangazeya sea passage through the Yamal portages, referring to the danger of Western European companies’ merchant ships appearing on the Ob and Yenisei [33, Belov M.I.]. Evidence was even presented that two European ships had been seen in Baydaratskiy Bay, near the western coast of the Yamal Peninsula. This petition was successful, since the attempts of English and German merchants to gain a foothold in the Russian northern lands during the recent Time of Troubles were still fresh in the memory.

In 1619, the Tsar’s decree banning it was signed. This ban had a negative impact on Pomor shipping and led to a decline in the Pomor territories. It hit, first of all, the poor Pomor peasants who sailed to Mangazeya. After the Mangazeya sea route was banned, anyone heading to Man-gazeya or Rus' could only use the overland “cross-stone route” (through the Ural Mountains) that led to Berezov or the “Kama road” through Verkhoturye to Tobolsk. Large sea kochs were built at these points and caravans were formed for trips to Mangazeya. Ships often had accidents in the Ob Bay due to strong storms [28, Butsinskiy P.N.]. Organizing trips along these routes was expensive and available only to wealthy merchants, and ordinary Pomors were engaged mainly as hired workers. This decision of the authorities heavily affected the peoples of Dvina, Mezen, Pinega, and Ustyug, who traded with Mangazeya. During the subsequent development of the eastern territories on the Yenisei and Lena, the main flow of industrialists went along the southern routes, bypassing Mangazeya, which completely lost its significance under these conditions.

The most important events in the history of Mangazeya

Table 2

The most important events in the history of Mangazeya

1600 — a detachment under the command of Prince Miron Shakhovskiy and the Head of the Streltsy Danila Khripunov was sent to the mouth of the Taz River with orders to establish a fort in order to bring the Yenisei and Mangazeya Samoyeds under the Tsar’s sovereign power and collect yasak from them annually. The subsequent fate of this detachment is unknown.

1601 — a second military expedition was sent to the Taz River region under the command of Prince Vasiliy Massalskiy and boyar Savluk Pushkin. The ostrog of Mangazeya was founded, in which they became the first voivodes. Construction of the voivode’s court in Mangazeya — the earliest building.

1604 — the initial fortress was built in Mangazeya.

1606 — voivodes Davyd Zherebtsov and Kurdyuk Davydov arrived in Mangazeya. The voivodeship authority in the North Siberian land was finally established.

1607 — construction of the Davydovskaya, Ratilovskaya, Uspenskaya, Spasskaya and Zubtsovskaya towers began. City fortifications were built.

1609 — in Amsterdam, the Dutch trade agent Isaac Massa published a geographical map of Mangazeya, which showed churches, the voivodes’ court and buildings.

1616 — Tobolsk voivode Kurakin reported to Moscow that the Germans hired Russians to lead them from Arkhangelsk to Mangazeya.

1619 — the Mangazeya sea route was banned (Pomor peasants were forbidden to sail from the Kara Sea to the Ob Bay and, under pain of death, to show the way to foreign ships). Large fire in Mangazeya, the city was burnt to the ground.

1626 — the “List" of the Mangazeya City was compiled, which was sent to the Siberian Prikaz. Restoration of the Assumption Church, the main church of the city.

1627 — the heyday of Mangazeya, about 700 industrialists “apart from new arrivals” spent winter in Mangazeya.

late 1620s — the Church of Macarius Zheltovodskiy (or the Church of the Holy Fathers and Wonder Workers Mikhail Malein and Macarius Zheltovodskiy) was founded in Mangazeya.

1629-1632 — boyar Grigoriy Kokorev with his retinue and nobleman Andrey Palitsyn arrived from Moscow to take over the voivodeship in Mangazeya. Internal strife between the voivodes. Defeat of Andrey Palitsyn (he retreated to the Yenisei portage).

since 1633 — the Siberian Prikaz began to appoint only one voivode to Mangazeya, who now owned the voivode’s court and all power in the city.

in the 1630s — the decline of Mangazeya began. The reason for this was the extermination of sable in this area, as well as the development of more convenient routes to the north of Siberia.

1641-1644 — caravans with bread did not come to Mangazeya. There was famine in the city.

1642 — a huge fire in Mangazeya, almost the entire city burned down.

1645 — the last big fire in Mangazeya.

1654 — the acolyte of the Trinity Church Alexey Antonov robbed the storeroom of the Man-gazeya Church of Macarius Zheltovodskiy.

1655 — according to the report of the voivode I. Sablin, from 700 to 1,000 fur trappers stayed in the city for wintering.

1660s — the cult of the holy martyr Vasiliy Mangazeyskiy appeared, who became the local church patron. Crowds of believers began to flock to the saint’s tomb, located in Mangazeya.

This did not help to restore the former power of Mangazeya, and the development of crafts and production practically ceased.

1672 — the Strelets garrison left the city of Mangazeya by order of the Tsar and moved from the Taz River to the Turukhansk winter camp. A new city was built here — New Mangazeya (Turukhansk). The old city, far from new trade routes, abandoned by people, fell into decay. Mangazeya did not exist for long, but it was a significant milestone in the advancement of the Russians to the east.

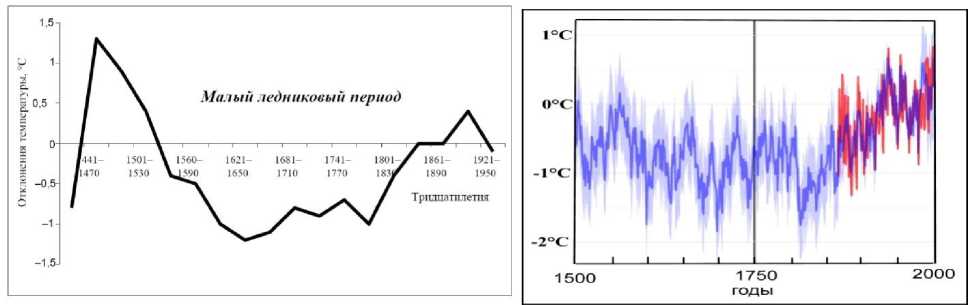

However, it was not only administrative decisions that affected northern navigation. When considering the history of navigation along the coast of the Arctic Ocean, it is necessary to take into account both long-term climate changes and annual temperature fluctuations in these areas. The period from the 14th to the 19th centuries was called the Little Ice Age. During this time, the lowest average annual temperatures in the last two thousand years were recorded (Fig. 18). People of the Middle Ages could not assess the impact of these changes, but now we can see the connection between the activity of Arctic voyages and climatic fluctuations, in particular changes in average annual temperatures. In the North, such temperature changes led to changes in ice conditions along the voyage routes, which in turn affected the accessibility of certain regions.

Fig. 18. Deviation of the average air temperature over 30 years in northern Eurasia from the average for the period 1881–1975, reconstructed from dendrological data [34, Krenke A.N.]; variations in average summer temperatures in the Arctic [35, Werner J.P.].

In this regard, it is clear that the beginning of fairly regular voyages of the Pomors to the mouth of the Ob from the Northern Dvina and Mezen region occurred in the middle of the 16th century, when the cooling in the Arctic had slowed down and had not yet reached its minimum during the Little Ice Age. At that time, the conditions for navigation in terms of ice conditions were more favorable. The throat of the White Sea, the straits in the area of Vaigach Island, and the waters around the Yamal Peninsula were free of ice. This undoubtedly contributed to active navigation along the northern coast and the penetration of industrialists into the territories at the mouth of the Ob. In the 1620–1630s, the period of relative warming in the North ended and the general cooling began, which sharply complicated the conditions for navigation. Besides, there were strong annual temperature fluctuations (Fig. 18 b), which affected the stability and regularity of voyages from year to year. Therefore, even without the Tsar's ban, the movement along the Man-gazeya Sea Route would most likely have gradually faded away. Later, in the middle of the 18th century, the participants of the northern detachments of the Great Northern Expedition encountered such sharply complicated weather and climate conditions; they had to describe long sections

REVIEWS AND REPORTS

Konstantin V. Lobanov, Mikhail V. Chicherov. “Gold-Boiling” Mangazeya … of the coast by foot routes, rather than by sea voyages, which were greatly hampered by the difficult ice conditions.

In 1629–1630, an unprecedented in the history of Siberian cities case of open hostility between two voivodes occurred in Mangazeya. Although conflicts with clarification of relations between voivodes appointed to one city occurred in other Siberian cities, only in Mangazeya it resulted in an armed confrontation between their supporters. After these events, the procedure for appointing voivodes to Mangazeya was changed. Since 1633, the Siberian Prikaz began to appoint only one voivode to Mangazeya, who now owned the voivode’s court and all power in the city. Gradually, the practice of appointing two voivodes to one city was abandoned in other Siberian cities.

The tragic events of 1629–1631 coincided with the beginning of the gradual economic decline of Mangazeya. The main reason for this was the reduction in the sable population as a result of uncontrolled hunting, which exceeded its natural growth. This led to the fact that more and more hunters began to leave for hunting in other areas on the Yenisei and further to the east. Business activity in the city began to decline, and fewer goods were delivered. The voivodes had to spend more time in the Turukhansk winter camp, solving various issues.

Fires, which devastated the city several times, posed a great danger to Mangazeya, as they did to all wooden cities. In the hot summer of 1642, a huge fire broke out in Mangazeya. Almost the entire city burned down. The voivode’s court, the sovereign’s granary, the assembly house, and part of the fortress wall burned down. Many half-burnt but not completely extinguished buildings had to be torn down for fear of a new outbreak of fire (Fig. 19).

(a) (b)

Fig. 19. The city of Mangazeya (a); fire in Mangazeya (b).

After the fire of 1642, Mangazeya was never rebuilt in its original form [13, Belov M.I.]. The entire archive of Mangazeya, located in the fortress, burned down in this fire. Therefore, only the documents that were once sent from Mangazeya to Moscow have been preserved for history. As to the cause of the fire, it was supposed that the town was set on fire by natives who had arrived in the city under the pretext of trade. By this time, relations with local residents had become strained, who, taking advantage of the impunity of the authorities, began to attack and kill industrialists, take away their furs and various supplies.

The situation was aggravated by the fact that in 1641–1644, due to unfavorable weather conditions in the Ob Bay, caravans of kochs with grain could not get through to Mangazeya from

Tobolsk. Famine began in the city. It became increasingly obvious that the city was losing its former significance, hindering the development of new territories and not bringing the same income to both industrialists and the treasury.

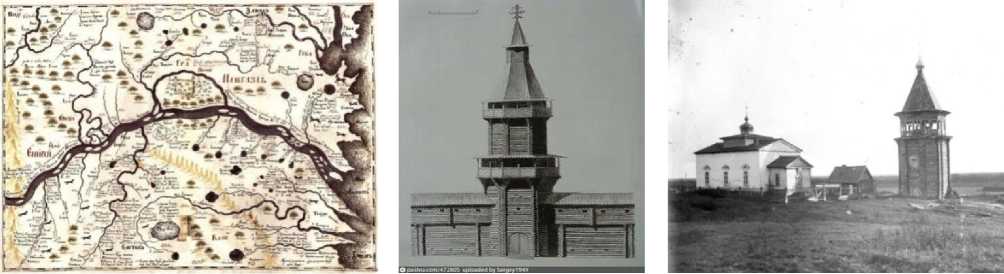

Taking into account these unfavorable circumstances, since 1650s, the Mangazeya voivodes started a long correspondence with Moscow about the need to move the city further east, where the center of the fur trade had already shifted. The residents began to leave the city, and business activity began to fade. In 1670, the relics of the Siberian saint Vasiliy Mangazeya were transferred from the deserted Mangazeya to the Trinity Monastery (Fig. 20), which had existed next to the Turukhan winter camp since 1660. Later, in 1720, by the order of the Metropolitan of Tobolsk Philotheus, they were placed in the ground in the southern half of the Church of the LifeGiving Trinity. Finally, in 1672, Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich issued a decree abolishing the city. Man-gazeya was finally abandoned in 1677, and its garrison and district leadership were transferred to the Yenisei to the Turukhan winter camp, which had existed there since 1607, and since 1660 — the Trinity Monastery. Having originally received the name of New Mangazeya, the fortress was later called Turukhansk (Fig. 20). The construction of the fortress was supervised by the last Man-gazeya voivode Danila Naumov, who built it in the image of the Mangazeya fortress. By 1677, the last residents left Mangazeya, and the city began to disappear gradually [8, Lobanov K.V.].

(a) (b) (c)

Fig. 20. Map of the city of New Mangazeya (modern Staroturukhansk) with its surroundings at the end of the 17th century (a)4; Gatehouse tower of the Turukhansk ostrog (b); Holy Trinity Turukhansk Monastery, bell tower with bells from Mangazeya (c).

The Tazovskoye yasak winter camp continued to exist on the site of Mangazeya until the end of the 18th century. In 1735, the winter camp was visited by a land detachment led by the geodesist student Fedor Pryanishnikov, and in the winter of 1737-1739 — by a detachment of the geodesist Mikhail Vykhodtsev. Both of these detachments belonged to the Ob-Yenisei detachment of the Great Northern Expedition under the command of Dmitriy Ovtsyn [36, Magidovich I.P.].

Conclusion

For centuries, despite all the difficulties, the Russian people steadily and consistently moved eastwards, mastering the vast expanses of northern Eurasia.

Book of maps of Siberia, compiled by Semyon Remezov, a boyar son of Tobolsk in 1701. URL: (accessed 20 July 2024).

The campaigns of the Novgorodians and then the Pomors made it possible to master Pomorie, the White Sea basin, the Kola Peninsula, protect them from foreign encroachment and gain free access to the Arctic Ocean. The sea voyages of the Pomors to the Arctic islands and along the northern coast of the Studenoe Sea marked the beginning of the development of the Northern Sea Route — the shortest route from Europe to China.

The northern lands became a source of inexhaustible resources, primarily furs, which were the basis for the economic development of the Russian state. Furs obtained in the North were practically the only export goods that made it possible to purchase goods that were not produced in Rus' abroad. These were, first of all, ferrous, non-ferrous and precious metals, materials necessary for the development of industry and defense capacity of the country. In fact, “soft junk” played the same role in foreign trade as oil and gas do today.

The construction and existence of Mangazeya, a large city in the center of the fur trade, played a huge role in the development and consolidation of this region for the Russian state. The city became the starting point for further advancement to the east. The sale of northern furs made it possible to overcome the economic decline of the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century and lay the foundations of a powerful state. At the same time, even in the most difficult times, it was possible to protect this region from capture by foreigners, preserving it for the Russian state.

Now the importance of these vast territories is only growing. The Northern Sea Route is the most important transport artery connecting the east and west of our country. This entire region is an inexhaustible source of resources that ensures the independent development of our country for many years to come.