Implementing active aging in the labor sphere (case study of the Republic of Komi)

Автор: Popova Larisa A., Zorina Elena N.

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Labor economics

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.13, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The goal of this paper is to investigate issues related to active aging and resource potential of the older population in the labor sphere: we assess the level and nature of employment of working pensioners and daily engagement of the unemployed in the conditions of reforming the Russian pension system. This topic is relevant due to Russia’s transition to the Western model of aging and the adoption of a law on raising the retirement age. The sources of information include official statistics and the findings of the sociological research “Problems of the third age” that we conducted in 2013 and 2018. After Russia had suspended the indexation of pensions to working pensioners, it witnessed a sharp decline in employment of old-age pensioners, which led to a decrease in their income level, lower employment potential of people of retirement age and a reduction in the duration of active life. Studies prove that age, education, and the type of locality, as well as gender-specific behavioral strategies in the workplace are among the strongest employment determinants for older people. There is a fairly stable employment structure in the older population: more than 70% retain their current job, more than 20% find unskilled jobs that are usually in demand among pensioners. As the age increases, not only does the share of working pensioners decrease, but also the percentage of those employed in the same workplace as before retirement decreases. Age discrimination typical of the Russian external labor market is duplicated by discrimination in the domestic market. The labor potential of older people is not utilized to its fullest extent: the reserve is more than 10%. People under 65 have a predominant desire to continue working, depending on their health status, working conditions, and the severity of the issue of double employment. In the five years that have passed between the surveys, unemployed elderly people became more engaged in activities beyond their home life; nevertheless, they are still mostly focused on their family and household.

Demographic aging, older population, active aging, retirement age, resource potential, labor activity, daily engagement, komi republic

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147225446

IDR: 147225446 | УДК: 316.621:331.5-053.88(470.13) | DOI: 10.15838/esc.2020.2.68.9

Текст научной статьи Implementing active aging in the labor sphere (case study of the Republic of Komi)

In the context of increasing life expectancy in Russia, the process of demographic aging has significantly accelerated, i.e. the proportion of the elderly is increasing. Demographic aging is rightfully recognized as one of the global challenges of our time. At the beginning of the 21st century, Russia adopted the Western model of aging, which is characterized by aging “from above”, i.e. a reduction in mortality in older ages, accompanied by a certain increase in the number of children. Since 2005, Russia has experienced an increase not only in the proportion of the population older than working age, but also in its absolute number1. In this regard, research on aging, a phenomenon that has various aspects and numerous economic, social and political implications, is becoming increasingly relevant; this requires expanding the range of related studies with an emphasis on recognizing that old age and other ages are equally valuable and that this period of human life has its own advantages [1–7].

In preparation for the Second United Nations World Assembly on Aging, which was held in 2002, the World Health Organization formulated a concept and a strategy for active aging [8]. According to the WHO, active aging is defined as “optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age”. In accordance with this, actions were formulated to preserve and improve the health of older people, involve them in various spheres of public life, including economic life, and create a safe physical, psychological, and social environment for them. The European Union selected three areas of action for the 2012 European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations. These areas are employment, participation in society, and independent living [9]. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe has defined active aging as a situation where people, as they age, continue to be formally employed in the labor market or participate in other unpaid productive activities (caring for family members and volunteering), and live healthy, independent and secure lives [10]. In accordance with this, when monitoring active aging, the Commission considers the following areas: employment (employment levels in different older age groups); participation in the community (volunteering, caring for children and grandchildren, caring for other adults, political participation); independence, health and safety of life (physical activity, access to health care, independent living, economic security, physical security); opportunities and favorable conditions for active aging (life expectancy at 55 years, the share of healthy life in life expectancy at 55 years, mental health, use of information and communication technologies, social ties, educational resources) [11].

In Russia, the socio-demographic policy aimed at creating conditions for active aging (maintaining health, physical activity, developing cultural interests, and ensuring conditions for participation in social life) is based on the Strategy for action in the interests of older citizens in the Russian Federation until 20252, approved by Government Resolution 164-R dated February 5, 2016. In 2018, in compliance with the May Presidential Decree3, the national project “Demography” for 2019– 2024 was developed; it includes five federal projects and the “Older generation” project. It focuses mainly on the health of the elderly, but the list of targets also includes the indicator “Number of citizens of pre-retirement age who have completed vocational training and additional vocational education”. Monitoring the results of the project’s regional programs, which include measures to increase the period of active aging and the duration of healthy life, involves assessing not only the health status of citizens older than working age, but also the number of older citizens engaged in physical culture and sports at newly created facilities and the number of those who have undergone retraining and training at specially organized courses, including computer literacy courses4.

Earlier, when we studied the problems of active longevity implementation, we considered the health of the older population in the context of the goals in the field of life expectancy in Russia [12]. Using the example of the Komi Republic, we assessed the dynamics of health status of elderly people in the context of a new wave of medical examination of the adult population in Russia [13]. Along with the development of health care, including specialized medicine, promotion of a healthy lifestyle, formation of a responsible attitude of citizens of all ages toward their health, prevention of the main modifiable risk factors for developing chronic diseases, early detection and adequate treatment of diseases, preservation of health of the older population are inextricably linked with the extension of the duration of a full and active life, which is largely determined by involvement in work [13].

In economically developed countries, quite a large number of scientists are engaged in research on the employment of the third-age population [14–20], since encouraging the employment of older workers, creating conditions for their successful adaptation to the changing requirements of the labor market, and effective use of their professional knowledge and intellectual potential are among the advantages of the Western social model. Russian socioeconomic research traditionally considers population aging mainly in the context of its negative economic implications such as an increase in the demographic burden on the working age population, the impact on the labor market and pension systems, and the need to provide social support to the elderly. At present, there are plenty of scientific works devoted to reforming the Russian pension system [21–28]; such works have become highly relevant in conditions of rapid demographic aging. They have become even more popular after a draft law on gradually raising the retirement age in Russia was submitted for discussion and a federal law on raising the retirement ages to 65 years for men and 60 years for women was adopted5.

The goal of our present article is to investigate the issues of active aging and implementation of the resource potential of the older population in the labor sphere: we assess the level and nature of employment of working pensioners and daily activities of the unemployed.

The information base for the study includes official state statistics data and the findings of the sociological study “Problems of the third age” that we conducted on the territory of the Komi Republic in 2018 (1,521 people over 55 years of age were interviewed, the sample is described in detail in [12]). Some questions were analyzed in comparison with the previous similar research (in 2013, 932 people of the specified age were interviewed, the sample and results are described in the monograph [29]). For different sample sizes, the main characteristics (by gender, age, type of settlement, education level, and family status) are almost identical, which makes it possible to compare the results of the two surveys. In addition to the gender distribution, the characteristics of the samples almost fully correspond to the population aged over 55. The marked excess of the share of women (75% of women in both samples compared to 63% in the general population [13]) is explained by the frequent refusal of men to participate in surveys.

Trends in the employment of retirement age population

Active aging is determined by a number of factors. In many ways, it depends on the ability of an individual to continue working after reaching retirement age – if they have the desire to work and do not lack physical abilities. Older people have important and necessary knowledge, social, professional and spiritual potential. Today representatives of the third age remain socially active longer, or at least strive to do so [30]. Researchers believe that employment in old age is caused not only by economic motives and lack of pension provision, but also by being in-demand and being included in social and professional relationships [4]. Specialists in the field of gerontology emphasize the importance and necessity of being employed at an older age. In their view, on the one hand, any form of age discrimination in relation to work should be excluded: age should not be an obstacle to working or studying, if there are no other restrictions to this goal. On the other hand, it is necessary to encourage the elderly themselves by constantly reminding them that the process of individual aging accelerates if there is a sharp decline in physical, intellectual and work load [3]. For example, working people over 55 years of age who participated in the 2018 survey rated their health status at 6.0 points out of 9 against 5.1 points among non-working people. Differences in the subjective assessment of health are particularly significant in working and non-working respondents over 75 years of age. In addition, aging society is characterized by a significant increase in life expectancy, including healthy life expectancy; this increase forms the basis of the so-called “second demographic dividend” at almost all ages. The dividend consists in the ability to use longevity to ensure sustainable social and economic development. Healthy and active aging will extend the period of employment, increase the number of working age population and reduce the demographic burden produced by the elderly [31–33]. In the context of aggravating economic challenges of demographic aging,

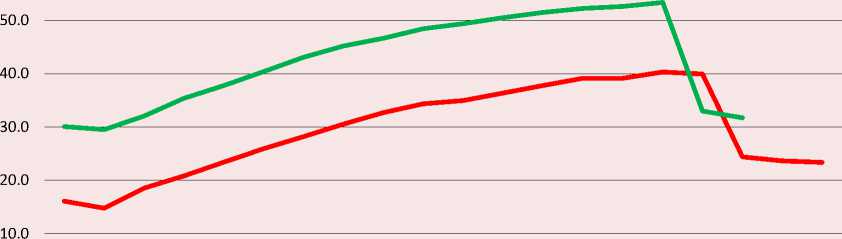

Proportion of employed old-age pensioners in the Russian Federation and the Komi Republic in 2000–2019

60.0

0.0

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

^^^^^^^ Russian Federation ^^^^^м Komi Republic

Sources: Official website of Rosstat. Available at: (accessed 22.11.2019); Statistical Yearbook of the Komi Republic. 2018: Statistics Collection. Komistat. Syktyvkar, 2018.

society should focus on the implementation of the “second demographic dividend”, i.e., on the fullest use of the labor potential of the older population.

During the 2000s, the share of working age pensioners in Russia was increasing continuously, reaching almost 40% in 2015– 2016 (Figure). In the Komi Republic, the employment rate of pensioners traditionally exceeds the nationwide level, since the age of retirement defined for the Northern territories determines the presence of a significant proportion of young pensioners. In 2011–2015, the share of officially employed pensioners in the region was above 50%. However, as of January 1, 2017, only 24.4% of pensioners were employed in the Russian Federation6. Then Komi witnessed a sharp decline in employment: from 53.3% on January 1, 2015 to 33.0% at the beginning of 2016, which was lower than the nationwide level, and to 31.7% at the beginning of 20177 (Komistat does not provide data for recent years so far).

This significant reduction in the employment of old-age pensioners is due to the adoption of Federal Law 385-FZ8 dated December 29, 2015, which suspended the indexation of pensions for working pensioners. Consequently, at least one third of pensioners employed in the economy received certain income from their work, which is in a certain way comparable to the losses in the amount of their pension, including prospective ones, due to the termination of its indexation. In the Northern regions, where pensions are higher than the nationwide level (in the Komi Republic, the average age pension in 2015–2016 was 16.3–16.7 thousand rubles9 in comparison with an average of 11.6–12.8 thousand rubles in Russia as a whole10), and their indexation accumulates from younger ages and, accordingly, is more noticeable at the psychological level, officially working pensioners reacted faster to the suspension of indexation. Some of them “withdrew into the shadows”, i.e. they continue working, but their employment is now informal. Some were forced to stop working, which not only reduced the level of income and generally reduced the use of the labor potential of people of retirement age, but also contributed to a decrease in the duration of active life of the population.

Features of working activity of the older population

The survey “Problems of the third age” investigates the standard of living and quality of life of the population over 55 years of age, identifies the main problems of older people, their health and social well-being, resources and opportunities. The survey contains a set of questions related to employment. In 2018, the retirement age in the Komi Republic was

50 years for women and 55 years for men, i.e. all respondents were of retirement age. One third of respondents (33.7%) gave an affirmative answer to the question “Do you work at present?” This almost corresponds to the level of official employment of pensioners in recent years and proves that the survey sample is sufficiently close to the general population for this feature; this fact increases the reliability of the analysis of employment-related questions.

Among employed respondents, almost two-thirds (65.9%) are employed full-time at the same place where they had worked before retirement (Tab. 1) . Another 7.0% of pensioners work part-time at the same place of employment. Consequently, more than 70% of the economically active participants of the survey (which is almost a quarter of all respondents) remained in their previous jobs; 16.2% are employed full-time at low skilled jobs that are most often taken by pensioners (janitor, caretaker, cleaner, cloakroom attendant, etc.). 6.6% of the employed have unskilled jobs on a part-time basis, 2.5% are owners of their own business. The remaining 1.8% of employed pensioners replied that they work at home, are engaged in network marketing, or work

Table 1. Distribution of answers to the question “If you are employed, then how can you describe your work?”

|

Answer |

Valid % (of the number of the employed – 513 people) |

Total % (of the number of survey participants – 1,521 people) |

|

I work full time at the job I had before retirement |

65.9 |

22.2 |

|

I work part-time (several days a week) at the job I had before retirement |

7.0 |

2.4 |

|

I work full-time at a job that pensioners usually take (janitor, caretaker, cleaner, cloakroom attendant, etc.) |

16.2 |

5.5 |

|

I work part-time (several days a week) at a job that pensioners usually take (janitor, caretaker, cleaner, cloakroom attendant, etc.) |

6.6 |

2.2 |

|

I work for myself (I have my own business) |

2.5 |

0.9 |

|

I am involved in network marketing (distribution of products) |

0.4 |

0.1 |

|

I work from home |

0.8 |

0.3 |

|

Other |

0.6 |

0.2 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

33.7 |

9 Statistical Yearbook of the Komi Republic. 2018: Statistics Collection. Komistat. Syktyvkar, 2018.

10 Official website of Rosstat. Available at: (accessed 22.11.2019).

full-time within their specialty in another organization, including non-governmental. The distribution of types and forms of employment of people over 55 years of age in 2018 is very close to the distribution we obtained in the 2013 survey [29, p. 45]. Apparently, it is a fairly well-established employment structure of the older population in the region.

As the age increases, the percentage of employed pensioners naturally decreases. Among the participants of the survey aged 55– 59, 63.3% are employed; 39.5% are employed among those aged 60–64, 23.4% are employed among those aged 65–69, 8.2% are employed among those aged 70–74, and 5.7% are employed among those aged 75–79. In comparison with 2013, the employment rate of young pensioners has slightly increased and the share of working pensioners over 65 years of age has significantly decreased. Apparently, the sharp decline in the employment of old-age pensioners after the suspension of pension indexation for working pensioners occurred at the expense of older age groups, who already experienced the increase in pension due to annual indexations.

Like in 2013, as people grow older, the proportion of working pensioners decreases; moreover, the percentage of full-time employees among them decreases as well. Over 75% of 55–59-year-old working respondents work full-time at the same place as before retirement, the figure in the 60–64-year-old group is 60%; a little more than half (53.8%) – among those aged 65–69, a little more than a third (35.7%) – among those aged 70–74, and only a third – among people 75–79 years of age. In other words, as their age increases, older people are forced to quit their job. It often happens that when people reach or even approach retirement age, they feel vulnerable in the domestic market of their company despite the fact that they have worked here for quite a long time. At the same time, older people in Russia have low competitiveness in the external labor market. In older working and retirement ages, it is quite difficult to get a new job within one’s specialty. Thus, according to the findings of a 2013 survey of managers of organizations and enterprises of various forms of ownership, only half of employers do not set age requirements for job candidates when recruiting employees [34]. In this regard, pensioners often have to comply with simpler forms of employment, sometimes with temporary or partial employment.

Discrimination against older workers in Russia appeared and became more acute during the period of socio-economic reforms in the 1990s, when the labor market in the country was just emerging. A sharp decline in production and a decrease in the number of traditional jobs at state-owned enterprises caused the displacement of pensioners from employment; “new” employers preferred to hire young people. Since the early 1990s, an open form of age discrimination emerged in the Russian labor market: job advertisements in which the main emphasis was placed on the age of the desired employees became widespread [35]. According to research estimates, age discrimination in employment in 2012 was almost twice as high as gender discrimination, although gender discrimination, in contrast to age discrimination, is often the subject of social research or discussion in the public sphere [36]. Amendments that prohibited discrimination in job advertisements were added to Federal Law 1032-1 “On population employment” only in 2013119. This has improved the situation to a certain extent; however, hidden discriminatory

11 Federal Law 162-FZ “On amending the law of the Russian Federation “On employment in the Russian Federation” and certain legislative acts of the Russian Federation”, dated 2.07.2013. Available at: ru/#/document/70405682/ (accessed 22.11.2019).

practices still remain, especially concerning high-paying jobs, for which employers prefer to hire 35–40-year-old candidates [37]. The refusal to hire an applicant can be based on any artificially created reason why the candidate is unfit for the position. At the same time, in Russia, it is the potential employee who will have to prove in court the fact of age discrimination when they were refused employment, and the employer is subject to the presumption of innocence, while the approach is fundamentally different in the European Union, the United States and Canada: the employer must prove that the principle of equality was not violated [35].

As in 2013, there is a clear direct correlation between the employment of the population over 55 years of age and the level of education. Forty six percent of respondents with higher education noted one or another type of work activity. Moreover, the vast majority of them (83%) remain at the same workplace as before retirement: 75% work full-time, 8% work part-time. Thirty three percent of pensioners with secondary vocational education have an employment, 72% of them are employed at the same workplace as before retirement: 66% work full-time and 6% work part-time. Twenty percent of the elderly with primary vocational education are employed (only 45% of them are at the same workplace as before retirement); 16% of pensioners without vocational education are employed (41% of them at the same workplace as before retirement). Of course, the dependence of employment on education may be partly due to the fact that pensioners from younger age groups have a higher level of education, but there is also a direct link between these characteristics for certain age groups.

The level of employment of pensioners varies significantly depending on the types of localities. Thirty nine percent of respondents over 55 years of age work in urban areas, 26% in urban-type settlements, and 25% in rural areas. Significant inter-settlement differences are caused not so much by the possibilities to preserve employment as by the difficulty to find a job such as watchman, cleaner, janitor, etc. in small settlement, i.e. the job that pensioners have more chances to get in the city (towns, and rural settlements in the Komi Republic have small population: the average population is about 3.5 thousand people). There are few such jobs in villages and towns, and they are usually occupied by working age people.

Despite the fact that the average age of men in the array of respondents is slightly lower than the average age of women (65 and 66 years, respectively) and their weighted average subjective assessment of their health is slightly higher than that of women (5.5 vs. 5.3 points out of 9) [13], the level of female employment is significantly higher: 35% compared to 29 for men. At the same time, as in 2013, women of retirement age are much more likely to continue working at the same place as before retirement: 75% of women vs. 65% of the surveyed working men over 55 years of age. It is clear that women are more likely to stick to their old job even if they are now paid less due to a part-time work schedule, while men who are determined to continue working after reaching retirement age are more active in looking for a new job in the current labor market or are engaged in their own business; 5.6% of working men over 55 years of age said that they work for themselves; the figure among women is 1.7%.

Reasons for termination of employment at older ages

Almost two-thirds (66.3%) of survey participants are no longer working. Almost all of them (with the exception of two people) answered the question why they are unemployed; some chose several answers. The vast majority (almost 64% of non-working respondents over 55 years of age) said they

Table 2. Distribution of answers to the question “If you are no longer employed, then why?”

|

Answer |

Valid % (of the number of respondents – 1,006 people) |

|

I am retired because I deserve to have a rest |

63.7 |

|

My age no longer allows me to work |

17.1 |

|

I can’t work due to health issues |

17.0 |

|

I have a lot of work to do at home, in the garden, at my dacha |

5.2 |

|

I need to help children raise their grandchildren |

4.3 |

|

The company (workplace) where I had been employed was shut down (cut) |

3.6 |

|

I had to leave my job because there is not enough work for young people |

3.0 |

|

I need to take care of my sick, elderly relatives |

1.4 |

|

Other |

1.1 |

|

Total |

116.3 |

“worked enough to deserve a rest” as the reason why they are unemployed (Tab. 2). We should note that in 2013, the question concerning motives for termination of employment was open-ended, the respondents formulated their answers on their own (the answer about the right to receive pension provision was the most common among them at that time as well). In 2018, we offered a question in the form of ready-made suggestions. It turned out that reaching the retirement age is quite a sufficient reason for quitting one’s job, i.e. a low retirement age does not inspire people to implement active aging strategies. Seventeen percent of non-working pensioners chose the answer “My age no longer allows me to work”. Such answers are common among respondents over the age of 75. Seventeen percent of respondents indicated their health status. This answer is most often found in the youngest age group, which indicates that at 55-59 years of age, it is the state of health that plays a significant role in deciding whether to continue working or retire. Young pensioners attach significant importance to the reasons associated with the need to raise grandchildren and care for sick or elderly relatives. Of course, these reasons are more common among women. In rural areas, the need to work at one’s private subsidiary plot is quite important. In general, the specified motive ranks fourth in the group of reasons for unemployment in the array. The answer option “I have a lot of work to do at home, in the garden, at my dacha” was noted by 5.2% of all respondents, in rural areas – 9.3%.

Almost 8% of the answers indicate a lack of jobs in one form or another, since almost all the answers in the group “Other” are included in the group. Moreover, the liquidation of an enterprise (workplace) is more of an urban phenomenon, and the answer “I had to leave my job because there is not enough work for the young” applies more to rural areas.

Some information about the attitude of older people toward employment is provided by answers to the question “Would you like to work now, being retired?” (Tab. 3). The question was addressed to all participants in the survey, so among the answer options there was the answer “I have a job”. This option was chosen by 20.4% of respondents. We remind that 33.7% of respondents answered affirmatively to the direct question “Are you currently employed?” Almost three-quarters of those who answered “I have a job” (74%) are employed at the same workplace as before retirement (67% work full-time, 7% work parttime), 17% work full-time and have an unskilled job. Thus, as in 2013, pensioners consider full-fledged employment as employment at same workplace as before retirement and as a full-

Table 3. Distribution of answers to the question “Now that you are retired, would you like to work more?”

|

Answer |

Total % (of the number of survey participants – 1,521 people) |

|

Yes |

24.9 |

|

No |

54.6 |

|

I work |

20.4 |

|

No answer |

0.1 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

time job that does not require high skills. Other income-generating activity is assessed as temporary and situational, and as the activity that people are forced to do due only to economic motives, need, and insufficient pensions. This activity is not satisfying and is less likely to prolong life expectancy in the older population.

An affirmative answer to the question “Would you like to work more now that you are retired?” was given by 24.9% of respondents. We note that 53.4% of them (13.3% of all respondents) were employed at the time of the survey. Obviously, they are not satisfied with their work and are ready to change it; 46.6% (11.6% of all respondents, a value almost identical to the one obtained in 2013 – 11.2% [29, p. 49]) are non-working pensioners who would like to get a job. That is, the reserve of labor potential of retirement age individuals, as in 2013, is more than 10%. Insufficient implementation of the resource potential of the older generations is due to the fact that in the labor sphere, the normative limits of working capacity/disability are determined by the retirement age. The retirement age, which at the time of the survey in the Komi Republic was 50 years for women and 55 years for men, sets benchmarks for determining a “suitable age” standard in the labor market. Moreover, research shows that not only people over working age are at risk of discrimination in the job search situation, but also a significant part of people of standard working age, i.e. about 10–15 years before reaching the retirement and even pre-retirement age threshold [36].

The lower the retirement age, the younger is age discrimination in the labor market and the greater is the reserve of underutilized labor potential of the older population, and the lower is the implementation of active aging strategies.

The majority of respondents (54.6%) gave a negative answer to the question concerning whether they want to work while being retired, i.e. more than half of people over 55 years old believe that they have already earned the right to have a rest. Of course, the prevalence of this answer is very closely related to age. At the age of 55–59, only slightly more than 25% of respondents prefer not to work anymore, at the age of 60–64 – 43%, at 65–69 – 64%, at 70– 74 – almost 80%, among people over 75 years of age – from 85 to 100%. Thus, as in 2013, the desire to continue working prevails until about 65 years of age, and in older ages, most of the respondents prefer a well-deserved rest.

The lack of desire to continue working after reaching the retirement age has an inverse relationship with the level of education. Forty eight percent of respondents with higher education, 54% of those with secondary vocational education, 64% with primary professional education, and 70% without professional education said they no longer wanted to work. The desire to take a break from work at the retirement age is more common among men, but the difference is statistically insignificant (56% vs. 54 for women), as well as in small localities (59% in rural areas and 62% in urban settlements vs. 52% in cities), which may be due to more difficult working conditions and engagement of residents of villages and settlements in household and noncommodity agricultural production. In other words, the desire to continue working after reaching the retirement age depends not only on age and good health, but also on the working conditions and the availability of sufficient free time to avoid double workload.

Daily engagement of non-working pensioners

Non-working elderly people were asked a question “If you are not working, how can you describe your engagement?” There could be several answers to the question. As in 2013 [29, p. 51], the most common answers were as follows: “I work at my private subsidiary plot, at my dacha” (43.0% of unemployed participants of the survey) and “I do household chores” (40.5%), which switched places; one more common answer was “I help my children care for my grandchildren” (37.1%; Tab. 4 ); 14.6% of non-working elderly people answered: “I do various crafts, sew, knit, do embroidery, etc.”. Given that the question suggested alternative answers, it can be concluded that at least 43% of non-working pensioners are very active in household management.

It is noteworthy that the percentage of unemployed older people engaged in community work has increased significantly, almost twice, as compared to the results of the 2013 survey: 15.6% compared to 8.3% in 2013. In this regard, the corresponding answer rose to the fourth position; 4.7% of the elderly write poems, memoirs, draw, and engage in other creative activities at their leisure (compared to 2.7% in 2013); 2.0% of officially unemployed older people note that they occasionally work within their specialty as before retirement; 4.8% of non-working pensioners wrote answers in the section “Other”. In contrast to the 2013 survey, when they were mainly related to household chores, the answers in 2018 mostly concern active, sport, creative and charitable activities; 9.1% of unemployed did not describe their engagement in any way.

In general, we can note that in the five years between the surveys, non-working people over the age of 55 have become more active outside their homes. However, family and household are still important to them. Before reaching 75, at least 35% of them not only do household chores, but also work at their dachas and private subsidiary plots, and more than one third of respondents help their children take care of their grandchildren. These types of engagement do not correlate with education; however, people with higher and secondary vocational education were more active in community work and in creative activities. In general, women answered this question more actively, so they are ahead of men in almost all types of daily engagement: in household and dacha, in helping their children

Table 4. Distribution of answers to the question “If you are not employed, please describe your engagement?”

|

Answer |

Valid % (of the number of unemployed pensioners: 1,008 people) |

|

I work in the garden, at my dacha |

43.0 |

|

I do household chores |

40.5 |

|

I help my children take care of my grandchildren |

37.1 |

|

I do community work |

15.6 |

|

I do various crafts, sew, knit, do embroidery, etc. |

14.6 |

|

I am engaged in creative work (I write poems, memoirs, draw, etc.) |

4.7 |

|

From time to time I work part-time within my specialty |

2.0 |

|

Other |

4.8 |

|

No answer |

9.1 |

|

Total |

165.8 |

Conclusions

Thus, after the suspension of pension indexation for working pensioners in Russia, there was a sharp reduction in the employment of old-age pensioners; this fact not only reduced their income level and reduced the use of the labor potential of people of retirement age, but also contributed to a reduction in the duration of an active healthy life. In the Northern regions, where the pension size is higher and its indexation occurs at younger ages, officially working pensioners have reacted faster to the suspension of indexation. Sociological surveys of the population over 55 years of age, conducted in 2013 and 2018, showed that age, level of education and type of locality are the most significant determinants for the labor activity of older people; there are also gender-specific behavioral strategies in the labor sphere. The structure of employment in older ages is quite well-established: over 70% work in their previous jobs as before retirement, more than 20% are engaged in unskilled work in the areas a pensioner can usually get a job. At the same time, the share of working pensioners decreases as their age increases, and the percentage of those employed in their previous jobs decreases: age discrimination typical of the Russian external labor market is duplicated by discrimination in the domestic market. This is largely due to the lack of jobs. The labor potential of older persons is underutilized. According to the results of both surveys, the reserve is more than 10%: more than a tenth of the respondents of retirement age are not employed, but want to work. People under the age of 65 have a predominant desire to continue working, which depends on the state of health, working conditions, as well as the severity of the problem of dual engagement: at work and at home. In the context of increasing economic challenges of demographic aging, society should focus on maximizing the employment potential of the older population in order to obtain a “second demographic dividend”. To do this, it is necessary to eliminate all manifestations of age discrimination in the labor sphere. Since the retirement age sets the benchmark in the construction of the “suitable age” standard in the labor market, its increase will help reduce ageism in employment and at least raise the age limit for the beginning of its manifestation, increase the use of the resource potential of the older generation and implement healthy and active aging strategies. The double standards introduced at the end of 2015 in the provision of pensions to working and non-working pensioners should be abolished – on the contrary, it is necessary to support the elderly and encourage and promote their employment. The unemployed elderly have become more active outside their homes in the five years between the surveys, but they are still mostly family-and household-oriented. At present, when population aging is accelerating, the need to improve the conditions for the involvement of all older people in socially useful activities is on the agenda. The primary task is to influence public consciousness purposefully and consistently in order to form a culture of aging and attitude toward the elderly.

Список литературы Implementing active aging in the labor sphere (case study of the Republic of Komi)

- Skinner B.F., Vaughan M.E. Enjoy Old Age: A Practical Guide. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

- Vincent J. Old Age. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Elyutina M.E., Chekanova E.E. Sotsial’naya gerontologiya [Social Gerontology]. Moscow, 2010.

- Rogozin D.M. Liberalization of aging, or work, knowledge and health in older age. Sotsiologicheskii zhurnal=Sociological Journal, 2012, no. 4, pp. 62–93. (in Russian)

- Rogozin D.M. Difficult life situations in the views of the older generation of Russians. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye peremeny=Public Opinion Monitoring: Economic and Social Changes, 2013, no. 5 (117), pp. 32–51. (in Russian)

- Collard F. Age groups and the measure of population aging. Demographic Research, 2013, vol. 29, art. 23, pp. 617–640.

- Isopahkala-Bouret U. Graduation at age 50 +: Contested efforts to construct “third age” identities and negotiate cultural age stereotypes. Journal of Aging Studies, 2015, vol. 35, pp. 1–9.

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing – A Policy Framework. A contribution of the World Health Organization to the Second United Nations World Assembly on Ageing, Madrid, Spain, April 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- European Union (2015). European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations (2012). European Implementation Assessment. Brussels: European Union.

- Active Ageing Index 2014: Analytical Report. UNECE/European Commission, 2015.

- Kutubaeva R.Zh. Analysis of life satisfaction of the elderly population on the example of Sweden, Austria and Germany. Population and Economics, 2019, no. 3(3), pp. 102–116. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.3.e47192 (accessed 22.11.2019).

- Popova L.A., Zorina E.N. Health status of the older population in the region as a factor in increasing life expectancy. In: Rossiya: tendentsii i perspektivy razvitiya. Ezhegodnik [Russia: Development Trends and Prospects.Yearbook]. Moscow: INION RAN, 2019. Issue 14. Part 2. Pp. 700–705. (in Russian)

- Popova L.A., Taranenko N.N. Assessment of elderly people’s health in the new campaign of medical examination of the population (case study of the Komi Republic). Sotsial’noe prostranstvo=Social Area, 2019, no. 5 (22). DOI: 10.15838/sa.2019.5.22.8. (in Russian)

- Walker A. Work and Income in the Third Age – an EU Perspective. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. Issues and Practice, vol. 19. no. 73. Studies on the four pillars (October 1994). Pp. 397–407.

- Appannah A., Biggs S. Age-friendly organisations: The role of organisational culture and the participation of older workers. Journal of Social Work Practice, 2015, vol. 12, no. 29(1).

- McVittie Ch., McKinlay A., Widdicombe S. Passive and active non-employment: Age, employment and the identities of older non-working people. Journal of Aging Studies, 2008, no. 22, pp. 248–255.

- Croix D. de la, Pierrard O., Sneessens H.R. Aging and pensions in general equilibrium: Labor market imperfections matter. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 2013, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 104–124.

- Bell D.N.F., Rutherford A.C. Older workers and working time. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 2013, vol. 1–2, pp. 28–34.

- Haza M. Longevity and lifetime labor supply: evidence and implications. Econometrica, 2009, November, no. 77, pp. 1829–1863.

- Kautonen T., Tornikoski E.T., Kibler E. Entrepreneurial intentions in the third age: the impact of perceived age norms. Small Business Economics, vol. 37, no. 2 (September 2011), pp. 219–234.

- Sinyavskaya O.V. Russian pension reform: where to go next? SPERO, 2010, no. 13, pp. 187–210. (In Russian).

- Shmelev Yu.D., Ishaeva A.D. Problems of reforming the pension system in the Russian Federation. Finansy=Finance, 2012, no. 2, pp. 50–53. (in Russian)

- Roik V.D. Pension reform: the concept of a social contract of generations of Russians for the 21st century is needed. EKO=All-Russian ECO Journal, 2012, no. 2, pp. 58–71. (in Russian)

- Kudrin A., Gurvich E. Population aging and risks of budget crisis. Voprosy ekonomiki=Economic Issues, 2012, no. 3, pp. 52–79. (in Russian)

- Solov’ev A.K. Actuarial forecast of long-term development of the pension system of Russia. Finansy=Finance, 2012, no. 5, pp. 57–63. (in Russian)

- Solov’ev A.K. Modernization of the pension system of Russia as a basic factor in sustainable socio-economic development of regions. In: Regiony Evrazii: strategii i mekhanizmy modernizatsii, innovatsionno-tekhnologicheskogo razvitiya i sotrudnichestva. Trudy Pervoi nauch.-prakt. konf. [Regions of Eurasia: strategies and mechanisms for modernization, innovation and technological development and cooperation. Proceedings of the First scientificpractical conference] RAN. INION. Moscow, 2013. Part 1. Pp. 324–327. (in Russian)

- Aganbegyan A.G., Gorlin Yu.M., Dormidontova Yu.A., Maleva T.M., Nazarov V.S. Analiz faktorov, vliyayushchikh na prinyatie resheniya otnositel’no vozrasta vykhoda na pensiyu [Analysis of factors that influence decision-making regarding the retirement age]. Moscow, 2014. Available at: http://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=23507815 (accessed 22.11.2019). (in Russian)

- Man’shin R.V., Luk’yanets A.S. Main directions for reforming the pension system of Russia in the conditions of population aging. In: Problemy demograficheskogo razvitiya gosudarstv Tamozhennogo soyuza i strategicheskie podkhody k dal’neishemu narashchivaniyu demograficheskogo potentsiala: mater. Mezhdun. nauch.-prakt. konfer. (Moskva, 13-14 oktyabrya 2015 g.) [Problems of demographic development of member states of the Customs Union and strategic approaches to further development of demographic potential: Proceedings of the international scientific-practical conference (Moscow, October 13-14, 2015)]. Moscow, 2015. Pp. 90–93. (in Russian)

- Popova L.A., Zorina E.N. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial’nye aspekty stareniya naseleniya v severnykh regionakh Rossii [Economic and Social Aspects of Population Aging in the Northern Regions of Russia]. Syktyvkar, 2014.

- Sheresheva M.Yu. Marketing of services for people of mature age: myths and real values. Vse plyusy zrelogo vozrasta=All the Advantages of Mature Age, 2014, no. 3, pp. 91–94. (In Russian)

- Lee R., Mason A. Some macroeconomic aspects of global population aging. Demography, 2010, no. 47 (1), pp. 151–172.

- Lee R., Mason A. et al. Is low fertility really a problem? Population aging, dependency, and consumption. Science, 2014, no. 346 (6206), pp. 229–234. DOI: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/346/6206/229.

- Sidorenko A. Demographic transition and “demographic security” in post-Soviet countries. Population and Economics, 2019, no. 3(3), pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.3.e47236 (accessed 22.11.2019).

- Galin R.A., Yapparova R.R. Use of the labor potential of persons of retirement age in the conditions of transformation of the demographic structure of the population. Region: ekonomika i sotsiologiya=Region:Economics and Sociology, 2015, no. 3 (87), pp. 171–189. (in Russian)

- Khotkina Z.A. “Normal labor potential” and age discrimination. Narodonaselenie=Population, 2013, no. 3, pp. 27–37. (in Russian)

- Kozina I.M., Zangieva I.K. Age discrimination in recruiting. In: Diskriminatsiya na rynke truda: sovremennye proyavleniya, faktory i praktiki preodoleniya. Mater. kruglogo stola IE RAN [Discrimination in the labor market: modern manifestations, factors and practices of overcoming. Proceedings of the round table of IE RAS]. Moscow, 2014. Pp. 50–63. (in Russian)

- Levinson A.G. Institutional framework of old age. Vestnik obshchestvennogo mneniya: dannye, analiz, diskussii=Bulletin of Public Opinion: Data, Analysis, Discussions, 2011, vol. 109, no. 3, pp. 52–81. (in Russian)