Intergenerational Differences of the Religiosity Level of Russian Arctic Residents in the Context of the Values Transformation in the Russian Society

Автор: Maksimov A.M.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 48, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article examines the problem of intergenerational dynamics of the religiosity level in post-Soviet Russia in the context of cultural transformations, combining the movement towards postsecularity and the domination of secular values of late modern societies. The paper analyzes the all-Russian data, obtained within the framework of the project “World Values Survey”, as well as data on religiosity and value orientations of the population of some Russian Arctic regions, obtained with the direct participation of the author. As a result of the analysis, the author verifies several hypotheses and comes to certain qualitative results. Firstly, there is a generational shift from traditional values to secular-rational values in modern Russia (according to R. Inglehart). The beginning of this process falls on the period of the socialization of the Millennial generation, the context of which is the economic and political reforms of the 1990-2000s. Secondly, the process of the intergenerational transformation of values is organically associated with a decline in the level of religiosity, but it is “delayed” by one generation. The author offers an explanation for this desynchronisation. Thirdly, it is shown that the religiosity level of the population of the Arctic territories is lower (in general and by generations) in comparison with the all-Russian religiosity level. The factors contributing to these differences, according to the author, are the relatively low share of Muslim population in the Russian Arctic and its high level of urbanization.

Religiosity, generation, value orientation, Russian Arctic, secularization, cultural transformation, World Values Survey

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148329251

IDR: 148329251 | УДК: [316.733+316.752+316.74](985)(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2022.48.144

Текст научной статьи Intergenerational Differences of the Religiosity Level of Russian Arctic Residents in the Context of the Values Transformation in the Russian Society

Over the past century and a half, one of the fundamental trends in the cultures of modernizing societies has been a gradual but steady (and in some cases very rapid and causing massive cultural shock) increase of secularism in public consciousness, accompanied by a loss of interest in religious practices, doctrines, and moral imperatives. This trend has become part of a broader value transformation that has swept industrial societies around the world. Despite the fact that a

∗ © Maksimov A.M., 2022

number of researchers note an increase in religiosity in certain regions, primarily those that are in the orbit of Islamic cultural influence [1, Gottlieb A., pp. 80–81], the general trend remains unchanged [2, Inglehart R., p. 139]. The religious revival observed in Russia in the first post-Soviet decade affected a significant part of the population [3, Markin K.V., p. 277], but, as we will try to show below, it has become more of a generational phenomenon than a sustainable progressive process.

In Russia, due to the multi-ethnicity of its population and deep regional differences, the levels of religiosity/secularity differ significantly among the subjects of the Russian Federation and even among territories of the same subject. However, Russia’s nationwide sample surveys do not adequately reflect these differences, especially in comparatively sparsely populated regions that are often overlooked by leading Russian researchers. This circumstance predetermines the importance of regional and local sociological studies for filling the existing empirical gaps: without claiming to make any broad generalizations, these works allow accumulating significant amounts of data that form the contours of the sociocultural portrait of the region, and, thus, create prerequisites for comparative interregional studies.

The present work belongs to this type of research. We verify three hypotheses in it:

-

• as the post-war generations change, there is a gradual decrease in the level of religiosity and an increase in secularism among the residents of the Russian Arctic;

-

• this process is part of a broader process of intergenerational transformation of value orientations;

-

• the European part of the Russian Arctic, excluding territories traditionally inhabited by indigenous peoples, due to the high level of urbanization, the industrial nature of the economy, the presence of scientific and educational centers and the composition of the population of mixed origin, is characterized by a lower level of religiosity than the Russian average, which includes regions with preserved elements of traditional society culture.

The theory of generations in Russian sociology

If we turn to the problem of conceptualization of the phenomenon denoted by the concept of “generation”, it becomes obvious that it is not essentially identical to the phenomenon that is defined through the term “age cohort”, which is widely used in statistics, demography, and often in sociology. According to the tradition laid down in the works of K. Mannheim, the boundaries of a generation are determined not so much chronologically, but through the general experience of socialization in specific historical and cultural conditions that differ from those of the previous and subsequent generations. According to Mannheim, people’s realization that their personal formation has taken place in specific historical conditions does not necessarily lead to a monolithic unity of values, worldview and political views, but sets the unity of the socio-historical “location” and a common range of meaningful life issues for these people. At the same time, within one gen- eration, separate “fractions” can be observed, the origin of which can already be associated with class, estate, professional differentiation within a generation [4, Mannheim K.].

In line with Mannheim’s ideas about generations as special socio-cultural communities that replace each other in time, the theory of generations was formed and developed in the second half of the 20th century. The modern version of this theory is usually traced back to the works of N. Howe and W. Strauss in the 1990s [5, Strauss W., Howe N.]. They proposed their own periodization of generations for the 20th century, which up to the present time remains very popular in various kinds of scientific and journalistic works. It is important to note that the empirical basis of the Howe-Strauss model was data on various aspects of life of the US population over the past century. This circumstance automatically implies the need for its adaptation, taking into account the historical, cultural and socio-political realities of the society to which it is planned to be applied. Examples of this kind of adaptation to the realities of the Soviet/post-Soviet society can be found in the works of a number of domestic researchers published over the past quarter of a century (for more details, see: [6, Maksimov A.M., pp. 5–6]).

Table 1 presents both the original periodization (generational change model) by W. Strauss and N. Howe, and its modifications, taking into account the specifics of the historical development of the USSR/Russia in the 20th - the beginning of the 21st centuries, authored by such prominent sociologists as Yu.A. Levada and V.V. Radaev.

Table 1

Models of generational change in the second half of the 20th - the beginning of the 21st centuries

It is easy to notice that V.V. Radaev’s and Yu.A. Levada’s intervals of birth and growth years are not identical for different generations; it reflects the idea of the uneven pace of the historical process and once again emphasizes the idea that generational boundaries do not coincide with the boundaries of age cohorts.

In the models presented, there is some variation in chronological boundaries for the same generations. As a result, the extreme age groups of each generation intersect with representatives of the “neighboring” generations that are close in age, which gives rise to the phenomenon of the so-called “echo generations”. In turn, this requires the allocation for each generation of its age “core”. Comparison of the age limits of generations in different models made it possible to solve this problem. The chronological framework of the “core” of the generation ranges from 9–15 years. The “thaw generation” included people born in 1930-1945, the Soviet “baby boomers” (“generation of stagnation”) — 1950-1965, “generation X” — 1971-1980, “millennials” — 1984-1993 and “generation Z” — 1997–2010.

Regarding the last generation, it should be clarified that referring its lower limit (by year of birth) to the beginning of the 2000s seems to be excessively conditional, if not formal. It is commonplace to say that the specific cultural context of Generation Z in which the socialization of its representatives takes place is the completion of the digital information and communication environment, the widespread use of mobile digital devices, the general availability of the Internet and the routine use of various digital gadgets. In Russia, all of the above occurred in the second half of the 2000s - early 2010s. During this period, those born after 2000 began to go to school, and people born in the second half of the 1990s were in their teenage years and adolescents. From this point of view, it is advisable to designate the approximate boundaries of generation Z in the range of 1995–2015, which does not contradict the placement of the “core” of generation Z in the time boundaries indicated above [6, Maksimov A.M., p. 7].

The phenomenon of religiosity in post-Soviet Russia

The return of the rhetoric of religious teachings to the public discourse, the political activation of religious organizations and movements, some external signs of clericalization — all these phenomena, observed today in many secular societies that have successfully passed the stage of modernization, prompted Western researchers to examine secularization theory more seriously and have triggered a broader discussion to revise their ideas about the very nature of the secularization process, how it occurred historically in Europe and beyond its borders, its universality and irreversibility, as well as the nature of the religious renaissance in developed countries [7, Gorski P.S., Altmordu A., pp. 68–75; 8, Inglehart R., pp. 3–32; 9, Possamai A., pp. 823–826].

One of the leading sociologists of religion, Adam Possamai, points out that the functioning of modern religiosity should be interpreted differently than religious institutions in traditional societies: in the context of global capitalism, the state of post-secularity [for more details see: 10, Habermas J.] reflects the way the elites of modernized societies make systematic efforts to integrate various kinds of religious groups. If successful, this reduces the potential for conflict between these groups (as well as between believers and non-believers), institutionalizes and controls their relationships, and allows the elites to appropriate the symbolic capital of religious leaders and organizations. Thus, the penetration of religious doctrines and practices into the public space is of a controlled nature, accompanied by their inclusion in a modern, secular in essence, culture and subordinates them to the norms of a secular state. As a result, there is not a desecularization of

Modern societies, but only a greater stabilization of their political and cultural subsystems [9, Pos-samai A., pp. 828–829].

Without delving into the question of the strengths and weaknesses of Possamai’s logic and the validity of his arguments, two conclusions follow from his interpretation, which make it possible to clarify the phenomenon of the post-Soviet flourishing of religious identities in Russia:

-

• the active presence of religious associations and their leaders in the public sphere of modern societies 1 is in most cases not accompanied by either a return to religious norms as regulators of routine social practices, or a massive rejection of secularized culture and rational perception of the world in favor of religious and mystical ideas;

-

• if the movement towards modernization at the initial stage was associated with the suppression of those religious groups that acted as agents of preserving the institutions and values of the traditional society, then in the future, the weakening of political pressure on these groups (which is one of the results of successful modernization) will lead to their hyperactivity and make the task of their reintegration into modern society urgent.

Political liberalization, which began in our country back in Perestroika and unfolded throughout the 1990s, caused a rapid increase in the number of those who defined themselves as believers, the majority of whom were Orthodox Christians, whose share increased almost threefold during the first post-Soviet decade [3, Markin K.V., p. 277]. At the same time, all surveys show an extremely low percentage of those who can be called church-bound, that is, they regularly practice religious rites and interact with representatives of the clergy, who know the basics of dogma and share the principles of religious morality [11, Emelyanov N.N., p. 35; 12, Zadorin I.V., Khomyakova A.P., p. 166, 180]. This confirms the above thesis about the preservation of the secular nature of thinking, values and corresponding habits in the modernized society among the majority of those who declare their religiosity.

There are several explanations for this phenomenon. The first one was proposed by the American sociologist Ronald Inglehart as part of his evolutionary theory of modernization. According to his approach, a systemic crisis within society and, as a result, a massive spread of a sense of insecurity of existence and uncertainty about the future, create conditions for a “conservative turn”, which can be expressed, among other things, in an increase in interest in religious doctrines and practices, religiously-communal foundations of social solidarity. The avalanche-like growth in the number of those who identify themselves with any religious group, which was observed in the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and in post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s, when the old system broke down and the country entered a phase of deep national crisis, represents is a vivid illustration of this mechanism [2, Inglehart R., pp. 144–145]. Indirectly, this effect is evidenced by individual studies of Russian scientists [13, Prutskova E.V., p. 129]. A consequence of this interpretation of the “explosive” growth in the number of Orthodox Christians in the first post-Soviet decade is the assumption that this growth was provided mainly by people born in the 1960s and 1970s, who were the core of the economically active population during the period of market reforms and should have been subjected to stress and frustration to the greatest extent in connection with the events taking place in the country. We verify this assumption on empirical data below.

Another possible explanation is related to the concept of “ethnodoxy”, which describes the phenomenon when ethnocultural identity is important for an individual, but his daily existence is no longer connected with traditional folk culture, and to reinforce his identity, the individual turns to bright external markers of ethnicity, such as the dominant religion in his ethnic environment (Russian is equal to Orthodox, Chechen is equal to Muslim, etc.). As a result, according to the principle of association, ethnic and religious identities are mixed [14, Karpov V., Lisovskaya E., Barry D., p. 644].

Finally, the mass declaration of belonging to the religious mainstream can be partially explained by the fact that if such religious teachings are supported by national or regional political elites, ordinary citizens perceive these teachings as elements of state ideology. Public adherence to Orthodoxy, if we are talking about Russia as a whole, or, for example, to Islam (in some subjects of the Russian Federation), performs the function of demonstrating loyalty to the state and its agents, including public opinion polls, which are often perceived as such [3, Markin K.V., p. 279]. This approach allows and explains the continued growth in the number of believers during the period of stabilization of the Russian economic system in 2000 - early 2010s: during this period, Russian millennials (generation Y) entered adulthood, the most politically conformist part of them in the conditions of political regime consolidation and its gradual rhetorical turn towards conservatism could be inclined to demonstrate their commitment to the dominant religious trends in the country. This assumption will also be tested empirically later in the text.

Religiosity of Russians in the context of intergenerational transformation of values

In order to characterize the level of religiosity of Russian citizens in general, as well as to describe the context associated with the dynamics of the value orientations of Russians, we turned to the data of the World Values Survey (WVS), cross-country comparative study, in particular, to the results of large-scale surveys of the 6th and 7th “waves” (2010–2014 and 2017–2020, the sample for Russia for the 6th wave was 2500 people; for the 7th — 1810 people).

In the WVS methodology, the axes “traditional values – secular-rational values” and “survival values – self-expression values” are singled out as key “value axes” [15, Welzel C., Inglehart R., pp. 48–56]. In specific societies, the value orientations of their members are distributed between the poles of these axes, reflecting the degree of adherence to one or another (traditionalist or modern/postmodern) value systems. Within the framework of this article, we are interested in the position of modern Russia along the first of two axes.

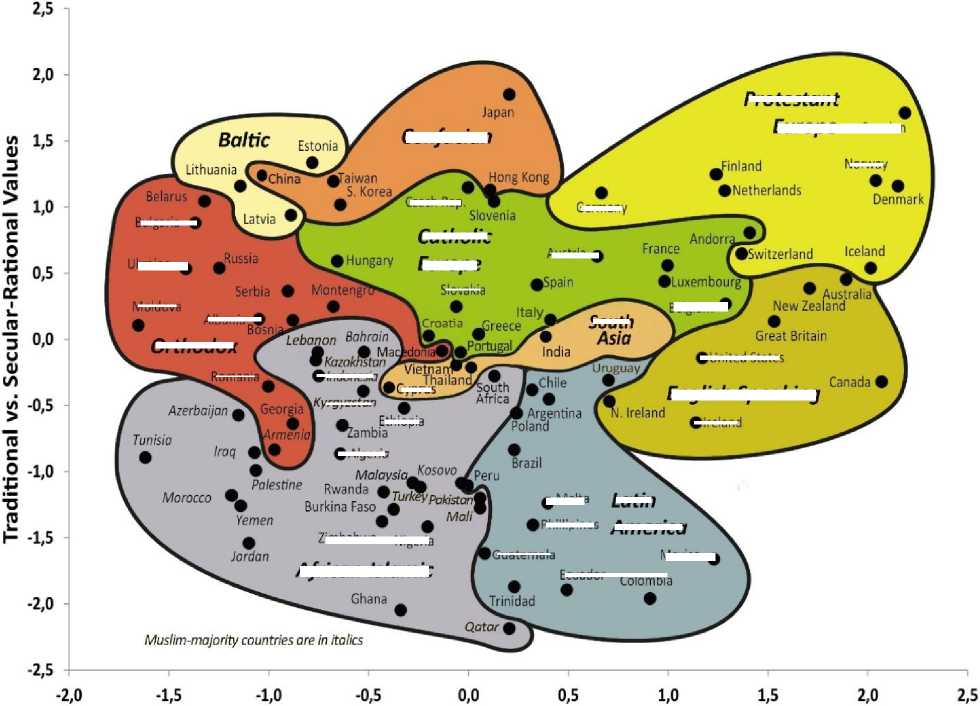

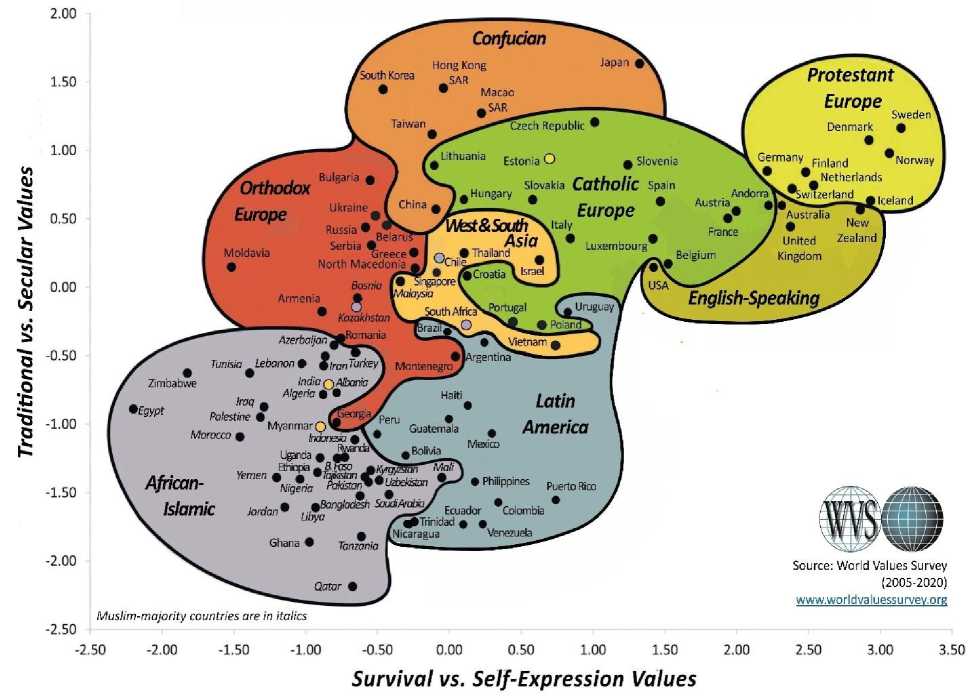

The position of Russia on the map of cultures (in terms of dominant value orientations in society) by R. Inglehart and K. Welzel is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Confucian

Norway

Czech Rep.

Germany

Bulgaria •

Austria a

Belgium •

South

Croatia

•United States

Romania

Cyprus

Л Algeria

Mexico a

'Indonesia

Latin

America

Catholic

Europe

Slovakia

English Speaking

•Ireland ж Malta

Phillipines

African-lslamic

Protestant

Europe Sweden

Guatemala

Ecuador yrgyzstan

Ethiopia

Moldova

Albania _9

Orthodox

Survival vs. Self-Expression Values

Fig. 1. World map of cultures by R. Inglehart - K. Welzel. Based on data from the surveys of the 6th wave of the WVS, 2014 2

Nigeria

In general, over the period between the last two “waves” of research, Russia’s position on the axis “traditional values - secular-rational values” has not changed — the country is located approximately in the middle of it. For comparison: the same position is taken, for example, by Austria and Iceland. The attitudes of the country’s population can be characterized as moderately secular and moderately conservative. However, the integral indicator of the degree of adherence to traditional (secular-rational) values aggregates a set of particular indicators — significant differences can be observed between countries that occupy a similar position in the system of cultural (in the sense of value systems) coordinates in certain parameters. One of these parameters is the religiosity of the inhabitants of a particular country (region).

2 The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map

—

World Values Survey 6 (2014). URL:

(accessed 08 January 2022).

Fig. 2. World map of cultures by R. Inglehart - K. Welzel. Based on data from the surveys of the 7th wave of the WVS, 2020 3

In the studies of R. Inglehart and his colleagues, a number of indicators are used to determine the level of religiosity, some of which allow for a comprehensive assessment of religiosity of followers of certain religious teachings (for example, some Christian denominations), while others are more universal in nature. Among the latter, the key ones are: 1) respondents’ assessment of the importance of religion in their daily lives, 2) respondents’ assessment of the degree of their adherence to any religious doctrine - identifying themselves as a religious, non-religious (indifferent to religious issues) person or an atheist.

According to the indicator of the religion importance in life (important in life: religion), there are no significant intergenerational differences in the 6th wave of the WVS, however, significant (p < 0.05) differences were recorded in the 7th wave, although the values for the indicator under consideration and for the age indicator are weakly correlated (Table 2). These differences arise due to the contribution of the youngest post-war generation: the value of its index of the importance of religion is not only higher in comparison with other generations, but also significantly exceeds the average value of the index for the sample.

A more detailed analysis of the data leads to the conclusion that for Russia as a whole, such a high value for this index among citizens born in the late 1990s and early 2000s is achieved at the

-

3 The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map - World Values Survey 7 (2020).

URL:

https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp (accessed 08 January 2022).

expense of regions with a high proportion of Muslims in their population. Thus, according to the results of a survey conducted in 2017, the share of Orthodox who, when asked about the importance of religion in their lives, answered “very important” was 17.6% (17.9% in 2011), and Muslims — 50.9% (36% in 2011) 4.

Table 2

Indicators of the importance of religion in the lives of respondents 5 by generation. Based on data from surveys of the 6th and 7th waves of WVS, 2011 and 2017, respectively 6

|

Wave 6 (2010–2014) 7 |

Wave 7 (2017–2020) |

|

|

Baby boom generation (1950–1965) |

0.65 |

0.60 |

|

Generation X (1971–1980) |

0.68 |

0.61 |

|

Generation Y (1984–1993) |

0.68 |

0.63 |

|

Generation Z (1997–2002) |

- |

0.73 |

|

For the sample as a whole |

0.67 |

0.64 |

Table 3

Distribution of respondents with different values of the indicator of the importance of religion in life by individual religious groups (data for Generation Z (born 1997–2002), in % (by line) 8

|

The importance of religion in life of respondents |

Confessional affiliation |

||

|

Does not belong to any religion |

Orthodox |

Muslim |

|

|

Very important |

14.3 |

0 |

85.7 |

|

Rather important |

11.5 |

76.9 |

11.5 |

|

Not very important |

56.8 |

40.5 |

2.7 |

|

Not important at all |

67.9 |

32.1 |

0 |

If we turn to the answers of respondents, whom we classify as generation Z, then 85.7% of those who indicated the high importance of religion in their lives are Muslims (Table 3). The share of such respondents in the group of Muslims of generation Z is 60%, more than among Muslims of any other generation (Orthodox zoomers, on the contrary, showed the lowest value of the indicator under consideration).

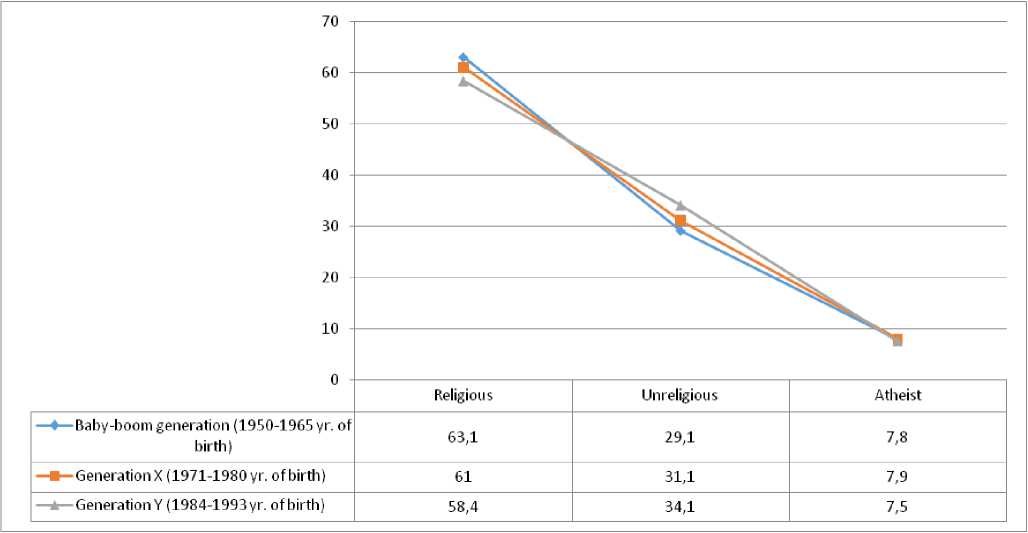

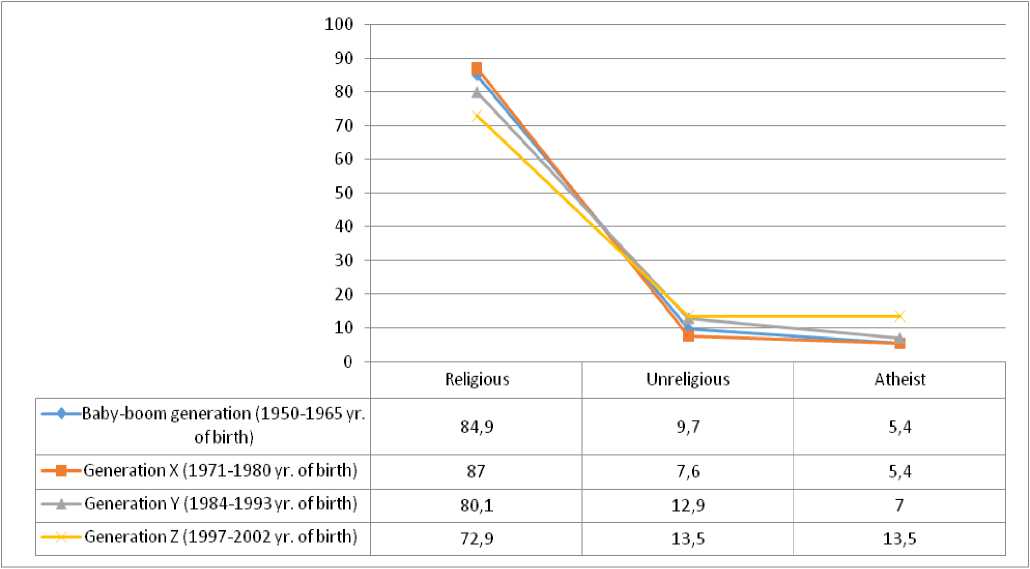

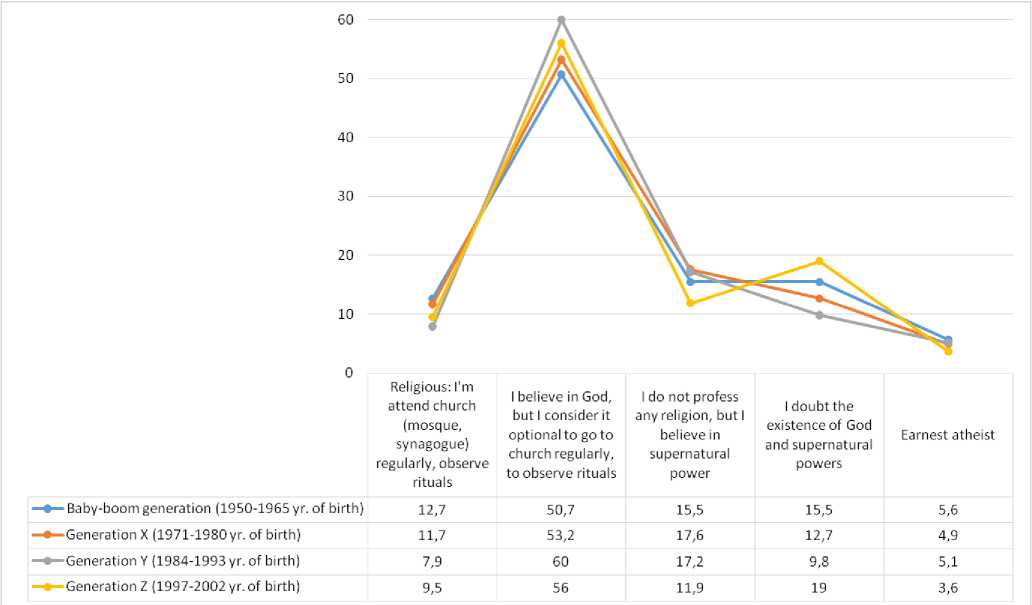

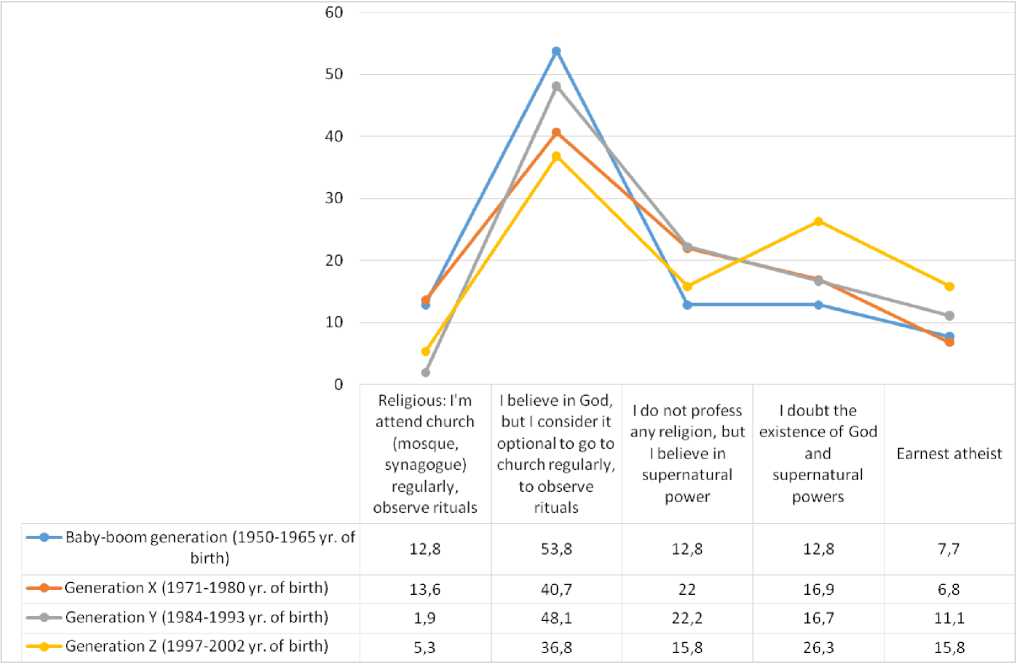

Figures 3 and 4 clearly show intergenerational differences in terms of religious selfidentification (identification with groups with varying degrees of declared religiosity).

Fig. 3. Distribution of respondents from different generations by level of religiosity based on declared religious selfidentification, in %. WVS. 2011, n=2500.

Fig. 4. Distribution of respondents from different generations by level of religiosity based on declared religious selfidentification, in %. WVS. 2017, n=1810.

The general conclusion from the data obtained can be reduced to two theses:

• all post-war generations, except generation Z (late 1990s-2000s), have a similar distribution between religious, non-religious and atheists; at the same time, as expected theoretically, there is a very high proportion of people among generations X and Y who identify themselves as believers; in 2017 survey, the percentage of such persons is noticeably higher compared to the shares of those who indicated the importance of reli-

NORTHERN AND ARCTIC SOCIETIES

Anton M. Maksimov. Intergenerational Differences of the Religiosity Level … gion in their lives; in other words, declared religiosity is growing, while the subjective significance of religiosity is declining — of all the theoretical explanations, the most relevant is the interpretation of the growth of declared religiosity as a demonstration of loyalty to the state and solidarity with the publicly broadcast ideology of the Russian elite, in which the conservative and statist components were strengthened throughout 2010s;

-

• representatives of generation Z, despite the increase in the number of those for whom religion is an important part of their lives, declare their religiosity to the least extent (in comparison with other generations) and to the greatest extent — religious skepticism and atheism; “digital natives”, thus, act as conductors of the global trend of post-secularity, when religious teachings, on the one hand, are not driven into marginal cultural niches, but on the other hand, adapting, they are built into a pluralistic (cultural diversity) culture, initially based on secular values.

Intergenerational differences in the level of religiosity of residents of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation

As an empirical basis for the analysis of intergenerational differences in the level of religiosity, determined through self-identification, data obtained during the implementation of the research project supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research “The influence of inter-generational differences in the value orientations of the population of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation on the economic development of its territories” (field stage completed in 2020), as well as (as a source of additional data) the materials of another project supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research “Value and cognitive factors of entrepreneurial behavior of the population of the Arctic territories of Russia” (field stage completed in 2018) was used. The author of this article was directly involved in both projects.

The 2018 survey included residents of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the Arctic territories of the Arkhangelsk Oblast. The sample (within the age limits set for the studied postwar generations) was 646 people. Since the research topic did not directly concern the religiosity of the inhabitants of the Arctic regions, only one indicator was used to measure the level of religiosity, based on the respondent’s self-identification with groups with varying degrees of adherence to religious beliefs, placed on a 5-rank scale (from those who not only declare their religiosity, but also indicates the regularity of visiting temples and observance of rituals up to persons who define themselves as atheists). We present these data (figure 5) in order to compare the level of religiosity of different generations over time (including identifying the possible effect of the COVID-19 pandemic) .

Fig. 5. Distribution of respondents from different generations by level of religiosity based on declared religious self- identification, in %. 2018, n=646.

In general, the 2018 data for the Arctic territories of the two constituent entities of the Russian Federation are consistent with the all-Russian pattern: equally high rates of declared religiosity in all generations and a relatively high proportion of religious skeptics among representatives of generation Z (as well as in the generation of the Soviet post-war Baby boom, which can probably be explained by the inertia of Soviet secular education in case of the most “indoctrinated” representatives of this generation).

In 2020, the author of the article, together with his colleagues from the FECIAR Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, conducted more than two hundred in-depth interviews with residents of four constituent entities of the Russian Federation, the territories of which are part of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation (“Arctic” municipalities of the Murmansk and Arkhangelsk oblasts, Nenets and Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous okrugs). The sample of interviewees was quota by gender, age and region of residence. Quotas were set in such a way as to have approximately equal representation of each of the studied generations in the sample. During the study, the emphasis was on obtaining qualitative data, but along with the interviews, a formalized survey of an exploratory nature was also implemented. The key goal of this survey was to identify common socio-cultural characteristics of the population of the regions of the Russian Arctic, represented by different generations, understood as socio-historical communities with similar cultural experience, values, attitudes and patterns of behavior. It was in the course of a formalized survey that both the level of religiosity of the inhabitants of the Russian Arctic and their value orientations were measured. Despite the fact that the total number of respondents (n = 212) is not enough to ensure high accuracy of the data, the random nature of the selection of respondents allows us to consider the sample representative and the data reliable enough to determine the most obvious intergenerational differences in the value systems of the respondents.

As part of our study, traditionalism/secularity (rationality) indices were calculated on the basis of ten variables borrowed from the questionnaire used during the 7th wave of the World Values Survey 9. These variables were used to measure the attitude of respondents to the values of work, family, religion, loyalty to the subjects of political power, tolerance for abortion, divorce, euthanasia, as well as the degree of expression of national pride. The variables were selected according to the principle of the highest correlation coefficients with the values along the axis “traditional values - secular-rational values” determined in earlier studies by R. Inglehart and K. Welzel [15, Welzel C., Inglehart R., pp. 49–53].

As indicators of the level of religiosity, the question of the importance of religion in the life of the respondent was used (a 5-rank ordinal scale), as well as the question of the respondent’s self-identification as a believer/non-believer (also a 5-rank ordinal scale with a qualitative description of its values). The index values for the first indicator demonstrate a linear relationship between the importance of religion and age: the older the respondents, the higher the corresponding values (table 4) 10. At the same time, checking the statistical significance of the relationship between two variables (belonging to a generation and the importance of religion), the Chi-square test gives a negative result (p> 0.1) — the difference in values is not so great as to talk about a significant cultural “gap” between generations, although the general trend towards growing secularism in consciousness from generation to generation is quite observable.

Table 4

Indices of the importance of religion in the lives of respondents 11 by generation. 2020, n=212

|

Index of the importance of religion |

|

|

Baby boom generation (1950–1965) |

0.62 |

|

Generation X (1971–1980) |

0.55 |

|

Generation Y (1984–1993) |

0.48 |

|

Generation Z (1997–2002) |

0.44 |

|

For the sample as a whole |

0.52 |

The connection between the belonging to a generation and the religious self-identification of respondents is even less evident. Chi-square testing also shows no statistical significance between the two variables. At the same time, some peculiarities can be noted in the answers of respondents belonging to different generations (Fig. 6). Thus, the representatives of the youngest generation who were born and/or socialized in the era of the total spread of digital technologies and the triumph of cultural globalization are the most prone to religious skepticism. They are also the least likely to identify themselves as believers.

It is worth noting that we found no significant correlations between the level of religiosity on the one hand and self-esteem of income or level of education on the other. Thus, neither fi- nancial status nor education, in contrast to generational affiliation, has any influence on religiosity among the residents of Russia's Arctic territories.

Fig. 6. Distribution of respondents from different generations by level of religiosity based on declared religious selfidentification, in%. 2020, n=212.

The data we obtained in 2020 are generally consistent with our own data for 2018 12, as well as with the nationwide data (World Values Survey) for 2017. The difference with the national trend is a lower level of religiosity among the population of the European part of the Russian Arctic in general and generation Z in particular. In our opinion, this is explained by the relatively insignificant proportion of Muslims in general and young Muslims in particular in the population of the surveyed territories 13, which somewhat correct the values of key indicators of the level of religiosity in the direction of their increase on the scale of Russia. The differences observed can also be explained by the higher level of urbanization in the Arctic regions: in comparison, the rural population is a better bearer of traditional norms and values, including religiosity, than the urban popula- tion.

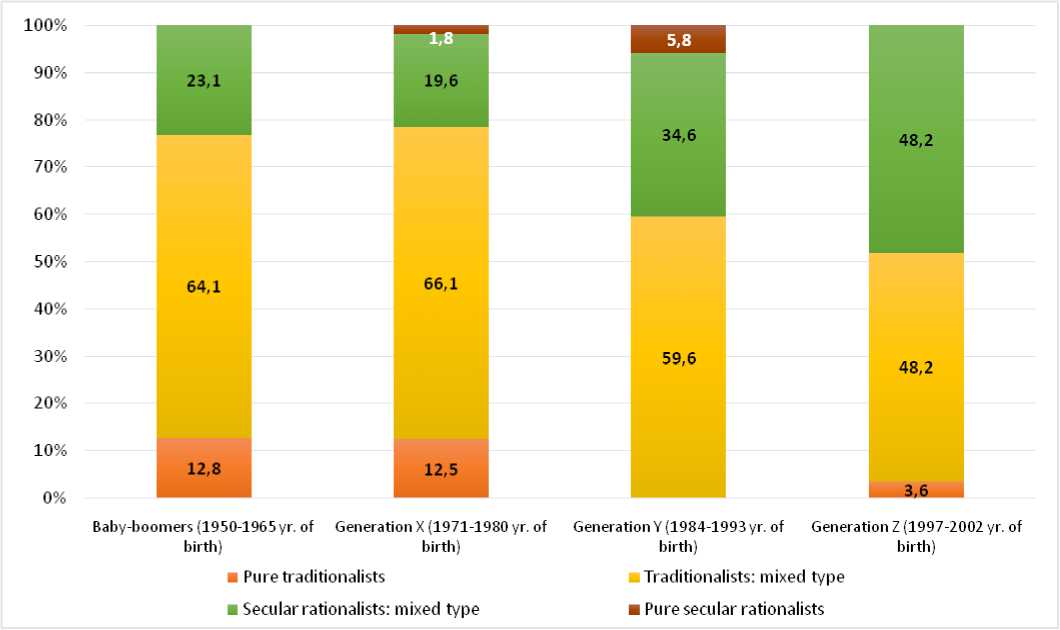

Finally, if we turn to the differences between the representatives of different generations on the axis “traditional values - secular-rational values”, we can find a clear trend towards the growth of secular consciousness and the rejection of traditional values (in the interpretation of R. Inglehart and K. Welzel) as the generations change.

Based on the calculated values of the traditionality/secularity (rationality) indices, we divided all respondents into four groups: pure traditionalists (absolute predominance of traditional values), traditionalists of a mixed type (an intermediate position on the axis “traditional - secular-rational values” with a pronounced inclination towards “traditionalism”), mixed-type rationalists (secular) (the same as in the previous group, but with a more pronounced shift towards secular-rational values), pure rationalists (the absolute predominance of secular-rational values). The resulting distribution by groups for each of the generations is shown in Figure 7.

It is easy to see that, starting from generation Y, which was included in the economic and political life of the country in the period of the 2000s, a trend towards intergenerational transformation of the value system towards an increase in the proportion of adherents of secular-rational values begins to appear. By now, in the surveyed Arctic territories, the largest share of the bearers of these values is in the Z generation, where their number is approximately equal to the number of “traditionalists”.

Fig. 7. Distribution of respondents from different generations by groups on the basis of differentiation of the index of traditional - secular-rational values, in%. 2020, n=212.

Conclusion

The analysis of empirical data reflecting the value orientations and religiousness levels of the population in Russia as a whole and in part of the territory of the Russian Arctic partially proved some of the hypotheses stated at the beginning of the article.

Firstly, using data from polls of the population of the Arctic territories of 4 subjects of the Russian Federation, it was found that there is a trend towards an intergenerational shift in the direction of secular-rational values; it started with the transition from the generation born in 1971– 1980 to the generation born in 1984 and early 1990s, which socialized mainly in the period after market reforms and democratic transition and till the post-Soviet political and economic system stabilized at the turn of the 2000s–2010s.

Secondly, the intergenerational decrease in the level of religiosity and, consequently, the increase in religious skepticism, although part of a broader process of the above-mentioned value transformations, is not synchronized with them, which is confirmed by both all-Russian data and data on the Arctic regions. The only generation that differs in any significant way in terms of the level of religiosity is the youngest post-war generation Z, whose representatives are just entering the status of full-fledged and economically active citizens. This lack of synchronism can be explained by rising declarative religiosity, associated with a demonstration of loyalty to the state and its agents: since conservative rhetoric has been growing in the public discourse of the political elite for the past 10-15 years, adherence to the dominant religious teachings in Russia is perceived by a significant part of the population as a component of state ideology.

Thirdly, the hypothesis of a lower level of religiosity in the Arctic compared to Russia as a whole was confirmed, which we attribute to a comparatively lower share of Muslims among their population, characterized by a higher degree of religiosity. An additional factor contributing to the lower level of religiosity of the residents of the Russian Arctic is its high degree of urbanization.

At the same time, for the purposes of a more subtle and in-depth analysis of the religiosity of the inhabitants of the Russian Arctic and its connection with the intergenerational transformation of values, large amounts of data are needed, which implies an expansion of the scope of sociological research in the territories of the Russian Arctic, primarily regionally oriented mass surveys of the population.

Список литературы Intergenerational Differences of the Religiosity Level of Russian Arctic Residents in the Context of the Values Transformation in the Russian Society

- Gottlieb A. Believe It or Not? In: Megachange. The world in 2050. London, The Economist and Pro-file Books, 2012, pp. 79–91.

- Inglehart R. Evolutionary Modernization Theory: Why People’s Motivations are Changing. Changing Societies & Personalities, 2017, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 136–151. DOI: 10.15826/csp.2017.1.2.010

- Markin K.V. Mezhdu veroy i neveriem: nepraktikuyushchie pravoslavnye v kontekste rossiyskoy sotsiologii religii [Between Belief and Unbelief: Non-Practicing Orthodox Christians in the Context of the Russian Sociology of Religion]. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: Ekonomicheskie i sotsi-al'nye peremeny [Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes], 2018, no. 2, pp. 274–290. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2018.2.16

- Mannheim K. Problema pokoleniy [The Problem of Generations]. Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie [New Literary Review], 1998, no. 2 (30), pp. 7–47.

- Strauss W., Howe N. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York, William Morrow and Company, 1991, 538 p.

- Maksimov A.M. Mezhpokolennye izmeneniya tsennostey naseleniya Rossii: metodologicheskie problemy issledovaniya [Intergenerational Values Change of the Russia' Population: Methodological Problems of Research]. Zhurnal sotsiologicheskikh issledovaniy [Journal of Sociological Research], 2021, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 2–12.

- Gorski P.S., Altmordu A. After Secularization? Annual Review of Sociology, 2008, vol. 34, pp. 55–85. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134740

- Inglehart R. Sacred and Secular Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2004, 329 p.

- Possamai A. Post-Secularism in Multiple Modernities. Journal of Sociology, 2017, vol. 53, no. 4, pp. 822–835. DOI: 10.1177/1440783317743830

- Habermas J. Religion in the Public Sphere. European Journal of Philosophy, 2006, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–25. DOI: 10.1177/0191453708098758

- Emelyanov N.N. Paradoks religioznosti: otkuda berutsya veruyushchie? [Religiosity Paradox: Where Do Believers Come From?]. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny [Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes], 2018, no. 2, pp. 32–48. DOI: 10.14515/monitoring.2018.2.02

- Zadorin I.V., Khomyakova A.P. Religioznaya samoidentifikatsiya respondentov v massovykh oprosakh: chto stoit za deklaratsiyami [Religious Self-Identification of Respondents in Mass Surveys: What Is behind Declared Religiosity?]. Politiya: Analiz. Khronika. Prognoz (Zhurnal politicheskoy filosofii i sotsiologii politiki) [The Journal of Political Theory, Political Philosophy and Sociology of Politics Politeia], 2019, no. 3 (94), pp. 161–184. DOI: 10.30570/2078-5089-2019-94-3-161-184

- Prutskova E.V. Religioznost' i bazovye tsennosti rossiyan (po dannym «Evropeyskogo sotsial'nogo is-sledovaniya i vserossiyskogo issledovaniya «Ortodoks monitor») [Religiosity and Basic Values of Russian Citizens (Based on the European Social Survey and the All-Russian Orthodox Monitor)]. Vestnik Pravoslavnogo Svyato-Tikhonovskogo gumanitarnogo universiteta. Seriya 1: Bogoslovie. Filosofiya. Religiovedenie [St. Tikhon's University Review. Series Theology. Philosophy. Religious Studies], 2017, no. 72, pp. 126–143. DOI: 10.15382/sturI201772.126-143

- Karpov V., Lisovskaya E., Barry D. Ethnodoxy: How Popular Ideologies Fuse Religious and Ethnic Identities. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 2012, vol. 51, no. 4, pр. 638–655. DOI: 10.2307/23353824

- Welzel C., Inglehart R. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2005, 333 p.