Interpretation of the Images of Qing Judges in the Illustrated Woodblock Editions and Popular Prints Nianhua

Автор: Ekaterina A. Zavidovskaia, Tatiana I. Vinogradova, Dmitri I. Maiatskii

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: История Восточной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.20, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The paper aims to analyze different types of illustrations of court case gong`an公案stories featuring Qing dynasty judges Shi-gong 施公 and Peng-gong 鵬公 found in the late Qing woodblock editions and popular woodblock prints nianhua年畫 in order to figure out how tales about imperial ‘fair officials’ have been reflected in book illustrations and in popular prints nianhua年畫. Popular prints from various Russian and foreign collections mostly depict episodes featuring Qing dynasty judges Shi Shilun (施世綸, dec. 1722), originally a protagonist of the novel “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” (施公案Shigong an, preface dated 1798), and Peng Peng (彭鹏, 1637–1704) from the novel “Criminal Cases of Judge Peng” (彭公案Penggongan, 1871) by Tanmeng Daoren貪夢道人. “Shi-gong plays” about Judge Shi and his friends gained popularity during the Daoguang period (1821–1850), however Judge Shi was no longer their central protagonist. The popular prints mostly depict martial scenes from these plays based on the court case stories. This research claims to define sources of various types of illustrations and clarify connections between book illustrations, popular prints and drama.

Court case stories, book illustration, play, popular print nianhua, Russian collection, martial scene

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147220276

IDR: 147220276 | УДК: 821.581 | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2021-20-4-53-67

Текст научной статьи Interpretation of the Images of Qing Judges in the Illustrated Woodblock Editions and Popular Prints Nianhua

Court case stories (公案小說 gong`an xiaoshuo) have been occupying a visible position in Chinese literary history since the Song dynasty. Our research pursuit is to revisit the perception of these stories by carefully interpreting its illustrative material and popular prints 年畫 nianhua. Since our scholarly lenses are focused on visual aspects of late imperial literature and drama, having checked both illustrated books and popular prints we were struck by the abundance of prints depicting mostly martial scenes from the stories about brave men helping the Qing dynasty judges 施公 Shi-gong and 鵬公 Peng-gong. Moreover, these images bear close ties with the plays, which were rather pop- ular among the urban population of the mid–late XIX century. The scenes depicted on the sheets ЛТ-4789, ЛТ-4790, ЛТ-4791, ЛТ-4793, ЛТ-5997, ЛТ-5999 1 from the State Hermitage and sheet № МАЭ 3676-19_1 from MAE RAS all represent scenes referred to as “eight big arrests” (八大拿 badana) 2, a term for eight plays about brave men helping Judge Shi. Some of them were rather popular among nianhua artisans, therefore prints have titles similar to those of the plays, e.g. “Arresting Luo the Fourth Tiger” (拿羅四虎 Na Luosihu, sheets ЛТ-4791, ЛТ-4793 from Yangliuqing). Sheets ЛТ-5998, ЛТ-5999 titled “Lake Luomahu” (落馬湖 Luomahu) feature protagonists sailing on a boat, while sheet ЛТ-5997 with the same title also from Yangliuqing represents a performance of this play on the stage. Yangliuqing sheet ЛТ-4788 titled “Village Xihuangzhuang” (溪皇莊 Xihuangzhuang) depicts a scene with Judge Peng kept hostage in a hall. Sheet ЛТ-5043 produced in Shanghai illustrates a battle scene from the “Criminal Cases of Judge Peng”, proving that battle scenes were a prevailing type of composition in illustrating court case tales in nianhua.

Originally court case stories existed as oral narratives, which later turned into plays during the Ming period, and a new wave of chivalric court case stories emerged during the mid-late Qing period; these stories served as a plotline for court case plays popular with urban audiences of the XIX – early XX centuries. What made “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” different from the criminal novels of the preceding periods is the prevalent role of chivalry ( 俠義 xiayi ) in the cause of establishing justice and protecting the judge. Among them Huang Tianba 黄天霸 , who had abandoned the path of banditry and rebellion becoming the official’s protector, serves as the most representative type of knight-errant in both “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” and “Criminal Cases of Judge Peng”. What interests us is the source of the battle scenes depicted on popular prints: did nianhua artisans watch the opera and produce the sketches based on their own observations, or did they follow some established canon of depicting the battles from these operas? This research intends to clarify this issue.

In his paper introducing literary features of the early “court case novel” ( 公案小說 gong`an xiaoshuo ) Dmitry Voskresenskiy quotes Lu Xun`s opinion about the novels telling stories of Judges Shi and Peng, saying that their “language is so coarse and poor that they can hardly be called ‘literature’” [Voskresenskiy, 1966. P. 108]. Lu Xun also criticized the political standing of these novels saying that their protagonists are just a bunch of messengers whose only joy is to serve the mighty ones [Tao Junqi, 1963. P. 27]. Robert van Gulik (1910–1967) misinterpreted Chinese court case stories as detective stories, while they are basically the opposite: they lack descriptions of the intellectual effort, focus on the military service rather than the investigation process per se. Renown judges should be seen as examples of the civil servant’s behavior rather than detectives. David Der-wei Wang saw the potential of Chinese court case stories to turn into the Western detective novel. He suggested a term “chivalry and judge cases novel” ( 俠義公案小說 xiayigong`an xiaoshuo ) for this hybrid type of novel [Wang, 1997. P. 117–118]. Novels “Three knight-errands and five righteous ones” ( 三俠五義 Sanxia wuyi , 1879) by Shi Yukun and “Criminal Cases of Judge Peng” ( 彭公 案 Penggong’an , 1871) basically adopted a structure similar to that of the “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi”. Tao Junqi places stories about Huang Tianba and Judge Shi in a row with other popular literary pieces reflecting common hatred for corrupted officials and local bullies of that period, such as “Cases of Judge Peng”, “Cases of Judge Yu” ( 于公案 Yugong’an ), “The Three Knights” ( 三俠劍

Sanxiajian ), “Tales of Brave Knights” ( 永慶升平 Yongqing shengping ) and the above-mentioned “Three knight – errands and five righteous ones” 3.

Overview of Qing Judge Shi and Peng novel editions

One of the earliest editions of “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” ( 施公案 Shigong’an , another title “Fantastic stories about Judge Shi cases” 施案奇聞 S hi’anqiwen, “Unusual Perspectives on One Hundred Judgments” 百斷奇觀 Baiduan qiguan , 1830) with the 1798 preface in nine juan and 97 chapters produced by Wendetang 文德堂 (Xiamen) is held at the British Museum. Some researchers consider 1798 to be the year of the book’s formation, which was preceded by a long period of Judge Shi stories circulating in the form of short plays and oral vernacular literature [Miao Huaiming, 2007. P. 64]. Scholars who have studied the history and reception of this novel generally agree that it was written in the late Qianlong (1735–1796) or early Jiaqing era (1796–1820) [Olivia Milburn, 2014. P. 118–119]. There were also the 1824 Benya 本衙 edition housed at Beijing Normal University (Reprint: Shi’anqiwen 施案奇闻 [Fantastic stories about Judge Shi cases] 。李德芳 点校 Collated by Li Defang 。 Beijing : Beijing shifandaxue chubanshe 北京师范大学出版社, 1993), 1829 Jinchangbenya 金閶本衙 edition and 1830 edition [Du Yajuan, 2007. P. 5]. Fu Sinian Library of Academia Sinica (Taiwan) holds a woodblock edition “Fantastic stories of Judge Shi” ( 施案奇聞 Shi’anqiwen , another title “Tales about Judge Shi`s Cases with Portraits” 繡像施公案傳 Xiuxiang shigong’an zhuan ) in eight juan and 97 chapters by Penglai 棚來 publisher dated 1839. A full account of early woodblock editions can be seen in the study by Miao Huaiming [Miao Huaiming, 2007]. In 1902 Shanghai publisher Wenxuan shujuguang 文宣書局光 published all ten sequels of the Judge Shi novel. A lithographic edition by Shanghai`s Guangyishuju 廣益書局 (1903) is kept in the library of Beijing Normal University. We would hardly be able to list all the late lithographic editions here due to their abundance.

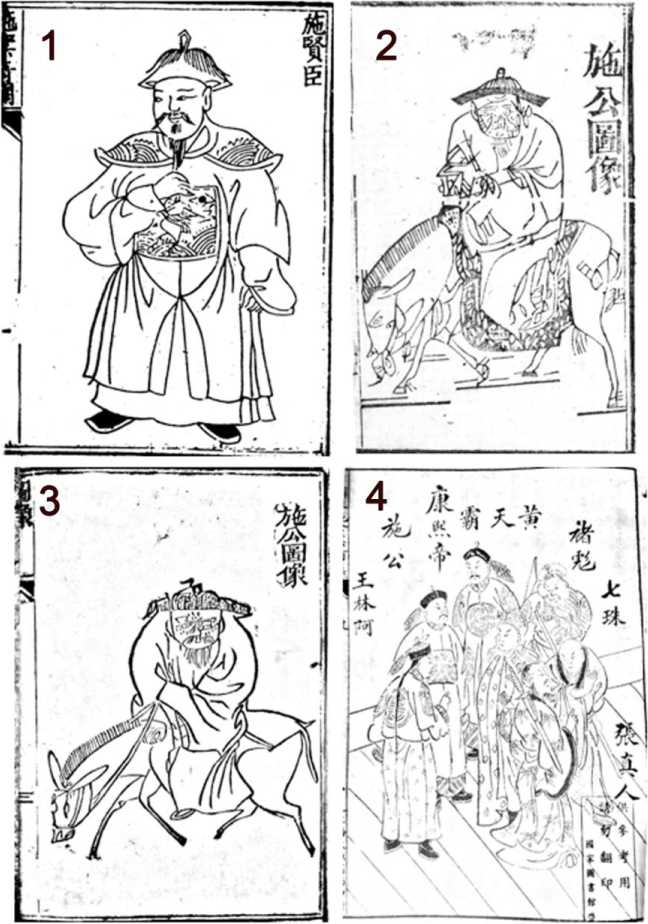

Illustrations of the earliest extant 1830 edition prove that warrior protagonists like Huang Tianba have not entered the gallery of portraits, which includes: Virtuous Official Shi 施賢臣 (Fig. 1, 1 ), Liu Yuan 劉元 , nee Wu 吳氏 , Hu Dengju 胡登舉 , Shi Zhong 施忠 , He Tianbao 赫天保 , Ni Qizhu 尼七銖 (appears in the plays), Seng Jiuhuang 僧九黄 , nee Dao 刀氏 , Li Kun 李裩 , Wu Tianqiu 武 天虬 (also present in the plays), Black-faced monk ( 黑面僧人 Heimian sengren ). They all are in standing posture without traces of theatrical attire. Judge Shi is depicted without theatrical make-up, with a beard and mustache, wearing a robe of a Qing official.

The St. Petersburg University library woodblock edition of “The Tale about Criminal Cases of Judge Shi with a Portrait” ( 繡像施公案傳 Xiuxiang shigong’an zhuan , ВУ147) was produced in 1874 by Jingdu Wenchengtang 京都文成堂 . It contains a portrait of Judge Shi riding on a donkey`s back (Fig. 1, 3 ), immediately bringing up associations with Laozi. This resemblance is enhanced by the fact that his outfit is similar to a Taoist`s robe. We suggest that the portrait of Judge Shi from ВУ147 copies the one from the earlier Penglai 棚來 edition “Fantastic stories of Judge Shi” ( 施案 奇聞 Shi’anqiwen ) in eight juan and 97 chapters dated 1839 (Fig. 1, 2 ).

In Chinese popular culture, donkeys are mentioned in old sayings “A donkey is not aware of his own ugliness” ( 驢不知臉醜 lübuzhilianchou ), “To ride a donkey with a book in hand – let’s see what happens next” ( 抱著書本騎驢子 — 走著瞧 baozhe shuben qi lüzi – zouzheqiao ). These meanings could be implied by the artist and may hint at the appearance of the judge. Only a beard and mustache are clearly seen on his face, while facial features are not distinct, because of many dots covering his face; does it imply that he used to suffer from smallpox? It is likely that this depiction

Fig. 1. Judge Shi portraits:

1 – from Wendetang (1830) edition, from: Shi’anqiwen [ 施案奇聞。上海:上海古籍出版社 ] Fantastic stories about Judge Shi cases. Shanghai: Gujichubanshe, 2002, juan 1. P. 5 (photo by author); 2 - from: Shi’anqiwen [ ЙЖ^Но®^ ] Fantastic stories of Judge Shi, Penglai, 1839, juan 1. P. 3, Fu Sinian Library, Taiwan (photo by author); 3 – from: Xiuxiang shigong’an zhuan [ 繡像施公案傳。京都文成堂 ]. The Tale about Criminal Cases of Judge Peng Shi with Portraits. Jingduwenchengtang, 1874. P. 3, Oriental Department of St. Petersburg University Library, ВУ147. (photo by author); 4 – portraits of Judge Shi and others, from: Dazi zuben xiuxiang shigong’an quanji [ 大字足本繡像施公案全集。 上海大成書局 ] Full Collection of Big Character Judge Shi Court Cases with Portraits. Shanghai dachengshuju, p. 3 (photo by author)

Рис. 1. Портреты судьи Ши:

1 – из издания печатни Вэньдэтан (1830), из: [Шианьцивэнь. Удивительные истории о делах, разобранных судьей Ши. Шанхай: Шанхай гуцзичубаньшэ, 2002, цз. 1. C. 5] (фото автора); 2 – из: [Шианьцивэнь. Удивительные истории о делах, разобранных судьей Ши. Пэнлай, 1839, цз. 1. С. 3, Библиотека Фу Сынянь, Тайвань] (фото автора); 3 – из: Сюсян шигунъань чжуань. О делах, разобранных судьей Ши, с портретами. Цзиндувэньчэнтан, 1874. C. 3]. Восточный отдел научной библиотеки СПбГУ, ВУ147 (фото автора); 4 – портреты судьи Ши и других, из: [Дацзы цзубэнь сюсян шигунъань цюаньцзи. Полное собрание дел, разобранных судьей Ши с портретами в больших иероглифах. Шанхай дачэн шуцзюй, C. 3] (фото автора)

symbolizes his ugliness. Importantly, this portrait is supplied by an inscription of “Praise for the portrait of Judge Shi” ( 施公像讚 Shigongxiang zan ) shown below:

汝身不長,

汝貌不扬。

胡爲邦家之柱石,

而爲生民負碩望。

汝外惡,

汝内臧。

寕獨德政之昭昭,

而實文章之宗匠。

嘻。微斯人也,

幾失子羽然明之相。 [Xiuxiang, 1874. P. 2]

You are not tall, nor boast conspicuous appearance.

You have become a pillar for the State, and an abode of hope for the people.

You look ugly, but have treasures inside you.

Have you gained glory only through virtuous governance?

Truly an outstanding master of literary writing!

Hey! The man though small, would he give in to the unattractive Ziyu and Ranming?

Praise for the portrait of Judge Shi consists of a title in 4 Chinese characters and of 55 words of the main text. The text is not marked with punctuation marks. It is written partly in the calligraphic style of lishu (“clerical script”), partly – in caoshu (“draft script”), which made it difficult to understand. Apparently, the board with this text was cut out by a hardly literate master, whose caoshu was rather poor, and he most likely did not fully understand the meaning of what he had carved. As a result some characters and their combinations were strongly transformed by him (for example, the verb 爲 “to be” was presented twice in different ways). The presence of a single type rhyme throughout the entire text with “-ang” at the end of each even line and grammatical parallelisms allows to divide the text into ten paired lines with the pattern 4-4-7-7-3-3-7-7-5-8, so that the first and second strokes have 4 characters each, the third and fourth – 7 characters each and so on. Each line represents an opposition, a technique that is very common in Chinese old literature. In the final line the judge is compared with Ziyu and Ranming – two famous politicians of the Zhou Dynasty, who were both wise and ugly.

Qing literati Gu Gongxie`s 顧公燮 “Leisurely notes from the country in summer” ( 銷夏閑記 Xiaoxia xianji ) has a description of Judge Shi’s appearance saying that “his appearance was bizarre, eyes look askew, weak hands, stumbling feet, slanting mouth”, needless to say that the portrait in the ВУ147 edition also portrays Judge Shi as a rather ugly person. But in the plays he was always presented as an elderly respected man character laosheng 老生 , whose inner moral beauty was combined with noble appearance, so these peculiar facial features of Judge Shi did not show on stage [Shao Zengqi, 1962. P. 15]. Olivia Milburn concludes that all surviving accounts of Shi-gong’s ugliness and disabilities appear to date from the late Qing Dynasty and therefore may be influenced by his portrayal in the “Fantastic stories about Judge Shi cases” [Milburn, 2014. P. 125].

The illustrations of the lithographic edition by Shanghai’s Guangyishuju (1903) portrayed the protagonists in fighting poses proving close ties with the operatic tradition rather than the one springing form the book tradition exemplified by Wendetang edition. The Republican period lithographic edition “Full Collection of Big Character Judge Shi Court Cases with Portraits” ( 大字足本 繡像施公案全集 Dazizuben xiuxiang shigong’an quanji ) by Shanghai dachengshuju 上海大成書 局 has several sheets with portraits, where protagonists are arranged in groups according to their participation in “eight big arrests”. Judge Shi is shown as a Qing official next to Kangxi Emperor, while Huang Tianba is shown wearing a stage costume; an interesting mixture of protagonists of the novel and plays about Judge Shi (Fig. 1, 4 ).

Evolution of the “court case plays” about Judges Shi and Peng

Oral narratives about Judge Shi existed during the early Jiaqing years (1796–1820), supposedly, the so-called “secret books” ( 道活秘本 daohuo miben ) used by story-tellers could have been released to the publisher, resulting in the production of the numerous “sequels” of the Judge Shi novel 施案奇聞 S hi’anqiwen 4 [Du Yajuan, 2007. P. 14]. Tao Junqi stresses that “Shi-gong plays” proliferated after the spread of the novel “Fantastic stories of Judge Shi” ( 施案奇聞 Shi’anqiwen ) and vernacular literary piece pingshu 評書 “Five Daughters and Seven righteous” ( 五女七貞 Wunü qizhen ), and the plays gained popularity mostly in Beijing during the Daoguang, Xianfeng and Tongzhi periods (1825–1874).According to Shao Zengqi, the novel “Fantastic stories of Judge Shi” ( 施案奇聞 Shi’anqiwen ) is a revision of the pingshu “Five Daughters and Seven righteous” with some changes and reductions. Peking Opera plays featuring Huang Tianba became well-known to the public throughout the XIX century, especially the plays titled “Fight with Lianhuantao” ( 連環套 Lianhuantao ), “Lake Luomahu” ( 落馬湖總講 Luomahu ) and “Evil tiger village” ( 惡虎村 Ehucun ) making Huang Tianba one of the favourites among theatre connoisseurs; the total number of “Shi-gong plays” amounted to thirty [Tao Junqi, 1963. P. 26]. The plots of the plays were mostly borrowed from pingshu “Five Daughters and Seven righteous”, the content and style of the plays were designed by the martial role actors 武生 wusheng who played leading roles [Shao Zengqi, 1962. P. 15, 16]. A famous wusheng actor and playwright Shen Xiaoqing ( 沈小慶 , 1808–1855) believed to be the author of “eight big arrests”, was also a rigorous listener of story-tellers and very likely could have heard narratives about Judge Shi [Du Yajuan, 2007. P. 7]. His plays became very popular during the Daoguang and Xianfeng periods (1821–1861). Judge Peng’s stories and short plays started circulating in Beijing during the Daoguang period (1821–1850), around which time there formed a pingshu “Judge Peng court cases” ( 彭公案 Penggong’an ), the novel by Tanmeng Daoren 貪夢道人 was published even later in 1871, but little is known about Judge Peng plays.

All the “Judge Shi” and “Judge Peng” plays were produced by drama troupes working in Beijing and gained popularity in the capital around the 1820–1830s. The novels bear strong Pekinese flavor due to the venue of their formation and proliferation. For instance, Peng-gong in the novel “Criminal Cases of Judge Peng”, originally a commoner from Fujian province who finally made it to the rank of Governor of Guangdong, was changed into a Manchu bannerman belonging to the 5th regiment of the Borderland Ren Banner; the novel mentions various locales of Beijing as well, moreover, these types of novels widely used Beijing dialect [Keulemans, 2014. P. 74]. However, we have found an impressive amount of popular lithographic prints from early XX century Shanghai also featuring “eight big arrests”, proving their popularity in the teahouses of Shanghai in the early XX century. These prints belong to the so-called xiaojiaochang 小校場 prints (“prints from the small parade ground”) tradition of Shanghai, discussed in more detail below.

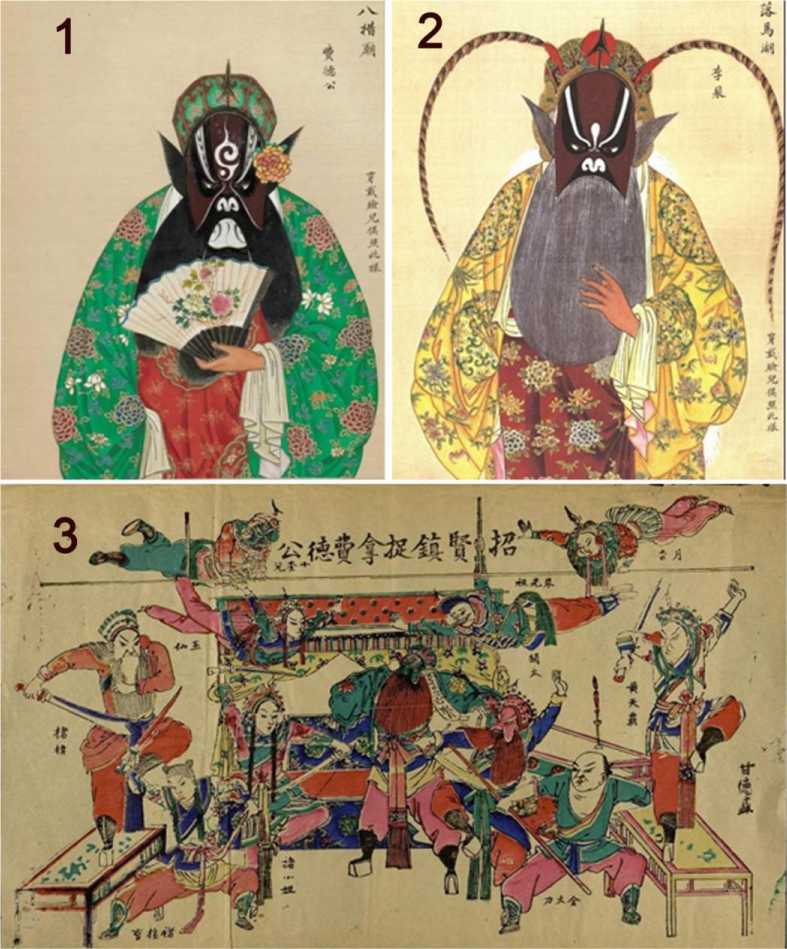

The novel about Judge Shi was not banned by the Qing government, therefore short plays featuring Huang Tianba entered the imperial stage during the Xianfeng period (1851–1861); famous wusheng actors Tan Xinpei (譚鑫培, 1847–1917) and Yang Xiaolou (楊小樓, 1878–1938) were invited to the palace to perform “eight big arrests” for Cixi Dowager [Yu Zhibin, 1962. P. 30]. The album titled “Praising the Ascending Peace” (慶賞昇平 Qingshang shengping, 1851–1874, kept at the National Library, Beijing) was produced by the Bureau of Ascending Peace (昇平署 Shengpingshu), which was in charge of imperial opera performances, supposedly it was made as a gift for Cixi Dowager. It featured portraits of the characters from two Judge Shi plays wearing costumes and make-up, including “Lake Luomahu” (ten portraits) and “Daoist Cai Tianhua” (Ж^ ^ Caitianhua, twelve portraits), these plays were introduced to the court by the Anhui troupe. Mei Lanfang Memorial Museum in Beijing holds another album belonging to the Bureau of Ascending Peace featuring two Judge Shi plays “Eight spirits temple” (八蠟廟 Balamiao) and “Ruler Ba`s Village” (霸王莊 Bawangzhuang) with a vertical line describing the actor’s make-up to the right from the portrait. These images give us a glimpse of the canonical attire of different characters from the “Judge Shi plays” and allow comparisons with the appearance of the characters in popular prints. Each villain from “eight big arrests” was supposed to have his own recognizable make-up colouring, and each of the “arrests” displayed one certain type of warfare, e.g. “Lake Luomahu” – a water battle, “Ruler Ba’s Village” – a daytime battle on the ground [Zhao Qi`en, 2016. P. 34]. Therefore each of the eight plays had its own special dangzi 檔子, a stage setting and a design of moves and tricks in the martial scenes illuminating the skill of the leading wusheng actor [Du Yajuan, 2007. P. 18]. We suggest that nianhua prints strived to illustrate the most brilliant dangzi of each play, so that such nianhua could be seen as a “visiting card” for a play. Below we examine how two out of “eight big arrests” plays were interpreted in popular prints.

Case of “Eight spirits temple” play

The play “Eight spirits temple” is based on chapters 305–310 (chapters 17–22 of the 5th sequel book) of the novel “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi”, which had undergone visible editing: the erotic content of the story was reduced, the part of Huang Tianba was exaggerated to grant him a central place on stage. Originally, a bandit leader Fei Degong 費德功 was supposed to have a fixed makeup made of three blobs of purple colour, a portrait from the palace album (Fig. 2, 1 ) gives an idea of this make-up, yet it is not completely the same on all nianhua that we have checked [Zhao Qi`en, 2016. P. 34]. Comparing several prints from Yangliuqing and Shanghai we quickly discover similarity in their composition with Fei Degong placed in the centre, next to him are Huang Tianba`s wife Zhang Guilan 張桂蘭 and a boy He Renjie 賀仁杰 , who were used as bait to lure out Fei Degong; Zhang Guilan is not present on some sheets [Zhongguo muban, 2009. P. 120–121]. These prints most likely depict a final scene, when the fort held by villain Fei Degong was captured by Huang Tianba`s friends, among them is also an old martial arts master Zhu Biao. A print from Shanghai “Capturing Fei Degong at Zhaoxianzhen village” ( 招賢鎮捉拿費德公 Z haoxianzhen zhuona Feidegong , ЛТ-5042) features characters with names different from those in the jingju opera (Fig. 2, 3 ).

Case of “Luomahu lake” play

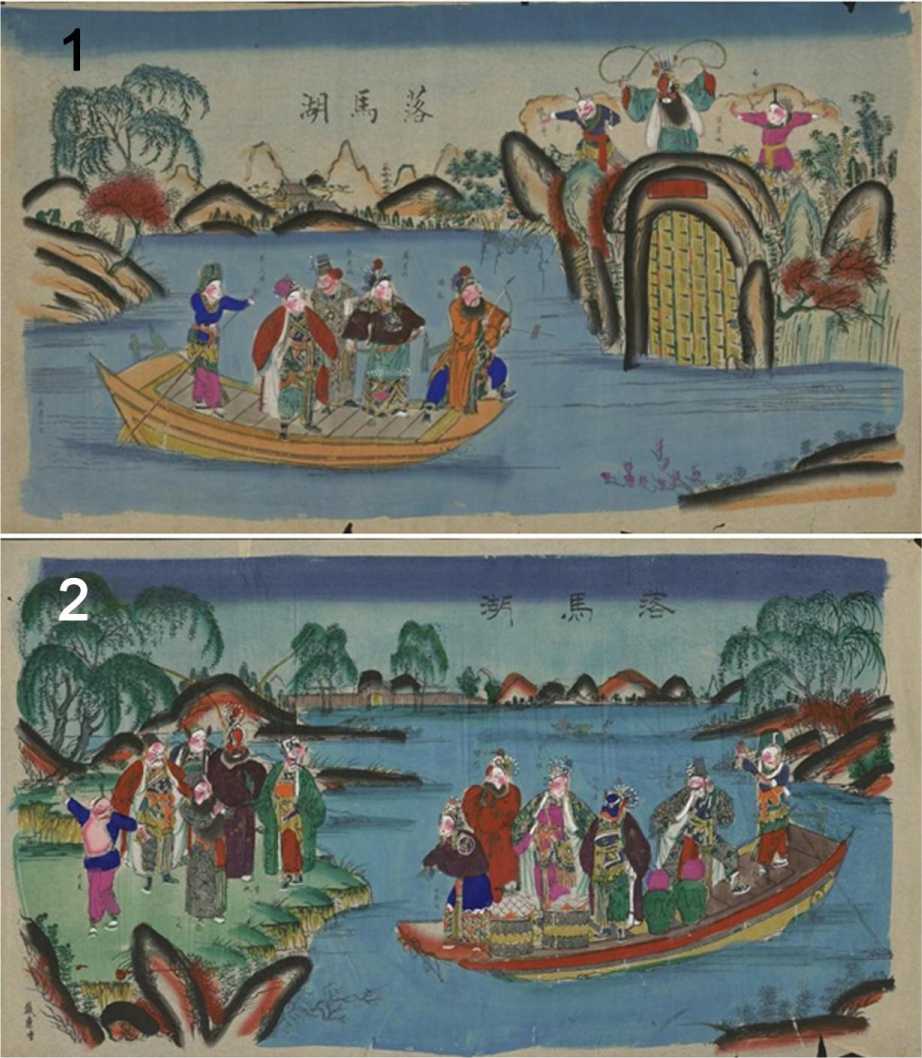

The play “Lake Luomahu” is widely present on nianhua prints produced in Yangliuqing and Shanghai. The play is based on the story from chapter 285 (or chapter 46 of the 4th sequel book) of the “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi”. Composition of the prints featuring this play has variations, but the villain 李佩 Li Pei is always recognizable due to two long pheasant feathers as part of his headdress (an attribute of a barbarian general, Fig. 2, 2 ). For instance, print ЛТ-5997 (Yangliuqing) depicts a stage performance with Li Pei seated and Huang Tianba standing next to him probably preparing to launch an attack on Li Pei (Fig. 3, 1 ) 5.

Sheet ЛТ-5999 (Yongqinghe shop, Yangliuqing) shows Judge Shi`s alliances Zhu Biao, Zhu Guangzu 朱光祖 , Wan Junzhao 萬君兆 sailing on a boat towards Li Pei stronghold with tablet “Luomahu” on it, a water battle is about to erupt, since Zhu Biao is pulling at his bowstring (Fig. 4, 1 ).

Fig. 2. Attire of the actor sperforming Fei Degong 費德功 , Li Pei 李佩 and popular print “ Capturing Fei Degong at Zhaoxianzhen village”:

1 – Attire of the actor performing Fei Degong 費德功 , from: Qingshang shengping [ 慶賞昇平 ] Palace album “Praising the Ascending Peace”. URL: https://kuaibao.qq.com/s/20190403A0LMGK00?refer=spider(accessed 30.11.2020); 2 – Attire of the actor performing Li Pei 李佩 , from: Qingshang shengping [ 慶賞昇平 ] Palace album “Praising the Ascending Peace”. URL: http://www.nlc.cn/newzqwqhg/qssp/lmh/201102/t20110215_36934.htm (accessed 30.11.2020); 3 – popular print “ Capturing Fei Degong at Zhaoxianzhen village” 招賢鎮捉拿費德公 (No. ЛТ-5042). The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg (photo provided by the Museum)

Рис. 2. Костюмы актеров, изображающих Фэй Дэгуна 費德功, Ли Пэя 李佩 и народная картина «Арест Фэн Дэгуна в деревне Чжаосяньчжэнь»:

1 – костюма актера, изображающего Фэй Дэгуна 費德功 , из: [Циншан шэнпин. Дворцовый альбом «Прославление мира». URL: https://kuaibao.qq.com/s/20190403A0LMGK00?refer=spider ] (дата обращения 30.11.2020); 2 – костюм актера, изображающего Ли Пэя 李佩 , из: [Циншан шэнпин. Дворцовый альбом «Прославление мира». URL: http://www.nlc.cn/newzqwqhg/qssp/lmh/201102/t20110215_36934.htm ] (дата обращения 30.11.2020); 3 - народная картина «Арест Фэн Дэгуна в деревне Чжаосяньчжэнь» 招賢鎮捉拿費德公 (No.ЛТ-5042).Государственный Эрмитаж, Санкт-Петербург (фото предоставлено музеем)

Fig. 3. Popular prints “Lake Luomahu” ( 落馬湖 ):

1 – (No.ЛТ-5997). The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg (photo provided by the Museum);

2 – (No.ЛТ-8217). The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg (photo provided by the Museum)

Рис. 3. Народные картины «Озеро Ломаху» ( 落馬湖 ):

1 – (№ ЛТ-5997). Государственный Эрмитаж, Санкт-Петербург (фото предоставлено музеем);

2 – (№ ЛТ-8217). Государственный Эрмитаж, Санкт-Петербург (фото предоставлено музеем)

However on the sheet ЛТ-5998 (Dailianzeng shop, Yangliuqing) we see villain Li Pei and his gang standing on the bank, while a group of men including Huang Tianba, Zhu Guangzu and Zhu Biao approach them on a boat, with Wan Junzhao politely greeting the men on the bank, since the plan was to capture Li Pei by using his son-in-law Wan Junzhao as a decoy (Fig. 4, 2 ).

Fig. 4. Popular prints “Lake Luomahu” ( 落馬湖 ):

1 – (No. ЛТ-5999). The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg (photo provided by the Museum);

2 – (No.ЛТ-5998). The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg (photo provided by the Museum).

Рис. 4. Народные картины «Озеро Ломаху» ( 落馬湖 ):

1 – (№ЛТ-5999). Государственный Эрмитаж, Санкт-Петербург (фото предоставлено музеем);

2 – (№ЛТ-5998). Государственный Эрмитаж, Санкт-Петербург (фото предоставлено музеем)

Print ЛТ-8217 (Hengyuansheng shop, Yangliuqing) shows yet another way of Wan Junzhao trying to deceive Li Pei. Hegemonic Li Pei and a warrior protecting him are shown standing on the bank of the lake, Wan Junzhao holds his hands in respectful greeting, Huang Tianba is next to him in a pose ready to fight (Fig. 3, 2). Examination of this series of prints allows us to suggest that these are different stages of the final part of the story.

Xiaojiaochang prints from Shanghai

During his travel to the Yangtze region of China in early 1909, Vasily Alekseev purchased hundreds of prints in Hankou, Suzhou and Shanghai, most of which are housed at the State Hermitage. Notably, prints illustrating stories of Judges Shi and Peng seem to have been produced in series by renowned Shanghai print shops: “Sunwenya” 孙文雅 (ЛТ-5043, “Capturing Huafeng at Xihuangzhuang village”, Judge Peng story), “Junxiangge” 筠香閣 (ЛТ-5044, “Huang Tianba destroying Ehu village”, Judge Shi story), “Jiuhezhai” 久和齋 (ЛТ-5053, “Judge Shi. Case of flying robber stabbing at Yin Family Fort”, Judge Shi story), “Muxinchang” 睦新昌 (ЛТ-4637, “Big havoc in Huaian residence”, Judge Shi story), “Gandesheng” 甘德盛 (ЛТ-6010, “Bright Dragon among the clouds and Phoenix Ridge”6, Judge Ji story). They all look like crowded fighting scenes. Prints from Shanghai have marks shang 上 (Shanghai), su 蘇 (Suzhou) and han 漢 (Hankou) in the corner, signifying the place of their purchase and therefore pointing at a large network of Shanghai prints distribution and popularity of this type of theatrical prints across the wide Yangtze river region.

Conclusion

This paper has taken a genre of chivalric court case stories about Judges Shi and Peng as a subject reflected both in late imperial illustrated editions and popular prints nianhua . We have discovered a key role of traditional opera as the medium through which court case stories became known to a wider illiterate public and showed how these prints could in a certain sense advertise and promote popular plays about “eight big arrests” based on Judge Shi`s stories. These plays with martial scenes were edited specifically for the newly emerging dynamic jingju genre. What may be considered an important outcome of this study is an assumption that court case plays were produced specifically for stage performances, moreover the artisans themselves watched them and produced their sketches based on personal impressions. Nonetheless, the compositions of the prints for “Eight Spirit Temple” and “Lake Luomahu” plays display a certain compositional pattern and depict the most breathtaking scene from the entire story, making the content of each print easily recognizable by the wider public. Therefore, the examined prints may be considered a reproduction of the real stage action, not a product of the artisans’ fantasies. Portraits of the actors from palace albums show just another facet of the universality of the cultural codes used in the drama performances. No matter where they were staged – in the yard, in the tea-house or the imperial palace, they all abided to the same set of symbolic patterns used in composing the traditional drama.

Miao Huaiming . Shigong an xinkao [ 苗懷明。《施公案》新考 ]. The re-examined “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi”. Zhongzheng daxue zhongwen xueshu niankan ( 中正大學中文學術年刊 Chung Cheng journal of Chinese studies). 2007, no. 10, p. 61–78. (in Chin.)

Milburn, Olivia . Strange stories of Judge Shi: Imagining a Manchu Investigator in Early Qing China. Ming Qing Studies , 2014, p. 117–139.

Tao Junqi . Guanyu Shigong an jumu de quxiangxing [ 陶君起。关于《施公案》剧目的趋向性 ] About tendencies of the “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” plays. Xijubao ( 戏剧报 Drama News), 1963, no. 06, p. 26–30. (in Chin.)

Shao Zengqi . Shigong’an he shigong xi [ 邵曾祺。《施公案》和施公戏 ] “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi” and ‘Shi-gong plays’. Shanghai xiju ( 上海戏剧 Shanghai Drama), 09.28.1962, p. 14–17. (in Chin.)

Yu Zhibin . Ruhe pingjia shigong xi: yu Shao Zengqi tongzhi shangque [ 于质彬如何评价 < 施公 戏 > :与邵曾祺同志商榷 ] How to evaluate ‘Shi-gong plays’: a discussion with Comrade Shao Zengqi. Shanghai xiju ( 上海戏剧 Shanghai Drama), 27.12.1962, p. 29–31. (in Chin.)

Voksresenskiy, Dmitry . Sudebnaia povest gong`an v Kitae. Court case novel in China. Narody Azii I Afriki ( Peoples of Asia and Africa).1966, no. 1, p. 107–115. (in Rus.)

Wang , David Der-wei. Fin-de-Siècle Splendor Repressed Modernities of Late Qing Fiction, 1848– 1911. Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1997, 433 p.

Xiuxiang shigong’an zhuan [ 繡像施公案傳 ] The Tale about Criminal Cases of Judge Peng Shi with a Portrait. Beijing, Wenchengtang 京都文成堂 , 1874. (in Chin.)

Zhang Wenshu . Jiacang guben Chewangfuquben shulüe [ 張文澍。家藏孤本《车王府曲本》述 略 ] Brief Account of the “Librettos from Che Prince Residence”. Zhonghuaxiqu ( 中华戏曲 Chinese Drama), 2015, no. 51, p. 214–221. (in Chin.)

Zhao Qi`en . Qianxi jingju badana dui shi-gong’an xiaoshuo de gaibian: yi balamiao weili [ 赵奇 恩。浅析京剧 “ 八大拿 ” 对《施公案》小说的改编 — 以《八蜡庙》为例 ] Primary analysis of how ‘eight big arrests’ changed the “Criminal Cases of Judge Shi”: case of “Eight spirits temple” play. Dawudai ( 大舞台 Big Stage), 2016, p. 32–34. (in Chin.)

Zhongguo muban nianhua jicheng. Ed. by Feng Jicai. Eluosi cangpinjuan [ 冯骥才主编。中國木版 ^ЖЖ^ . #ЖЖЖй#]. Compendia of the Chinese woodblock New Year pictures. Volume from the Russian collections. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2009, p. 1009. (in Chin.)

Мяо Хуаймин . «Шигунъань» синькао[ 苗懷明。《施公案》新考 ]. Новое исследование «Дел, разобранных судьей Ши» // Чжунчжэн дасюэ чжунвэнь сюэшу нянькань ( 中正大學中文 學術年刊 Научный ежегодный журнал китаеведных исследований университета Чжун-чжэн). 2007. № 10. С. 61–78. (на кит. яз.)

Сюсян шигунъань чжуань [ 繡像施公案傳 ]. Сказание о Делах, разобранных судьей Ши. Пекин: Цзиндувэньчэнтан 京都文成堂 , 1874. 80 c. (на кит. яз.)

Тао Цзюньци . Гуаньюй «шигунъань» цзюйму дэ цюйсянсин [ 陶君起。关于《施公案》剧目 的趋向性 ]. О тенденциях в пьесах по «Делам, разобранным судьей Ши» // Сицзюй бао ( 戏剧报 Новости драмы). 1963. № 6. С. 26–30. (на кит. яз.)

Чжан Вэньшу . Цзяцангубэнь «Чэванфуцюйбэнь» шулюэ [ 張文澍。家藏孤本《车王府曲 本》述略 ]. Краткое описание сохраненной в семье «Книги пьес из резиденции Чэван-фу» // Чжунхуа сицюй ( 中华戏曲 Драма Китая). 2015. № 51. С. 214–221. (на кит. яз.)

Чжао Циэнь . Цяньси цзинцзюй «бадана» дуй «шигунъань» сяошо дэ гайбянь: и «Баламяо» вэйли [ 赵奇恩。浅析京剧 “ 八大拿 ” 对《施公案》小说的改编 — 以《八蜡庙》为例 ] Предварительные изыскания о том, как «восемь больших арестов» повлияли на «Дела, разобранные судьей Ши»: на примере пьесы «Храм восьми духов» // Даутай ( 大舞台 Большая сцена). 2016. С. 32–34. (на кит. яз.)

Чжунго мубань няньхуа цзичэн. Элосы цанпинь цзюань [ 冯骥才主编。中國木版年畫集成 . 俄 ЖЖЖй^] Собрание ксилографических картин Китая. Под ред. Фэн Цзицая. «Из собраний России». Пекин: Чжунхуа шуцзюй, 2009. 1009 с. (на кит. яз.)

Шао Цзэнци. «Шигунъань» хэ «шигунси» [ 邵曾祺。《施公案》和施公戏 ] «Дела, разобранные судьей Ши» и «пьесы о судье Ши» // Шанхай сицзюй ( 上海戏剧 Драма Шанхая). 09.28.1962. С. 14–17. (на кит. яз.)

Юй Чжибинь . Жухэ пинцзя «шигун си»: юй Шао Цзэнци тунчжи шанцюэ [ 于质彬如何评价 < 施公戏 > :与邵曾祺同志商榷 ]. Как оценивать «пьесы о судье Ши»: дискуссия с товарищем Шао Цзэнци // Шанхай сицзюй ( 上海戏剧 Драма Шанхая). 27.12.1962. С. 29–31. (на кит. яз.)

Материал поступил в редколлегию Received 24.12.2020