Leader program: development potential for rural life improvement

Автор: Mt Pter, Tth Tams

Журнал: Региональная экономика. Юг России @re-volsu

Рубрика: Фундаментальные исследования пространственной экономики

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.10, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Without knowledge of the past, it is impossible to build the future, therefore, it is necessary to comprehend the processes that have already taken place, if only because it will allow us to learn lessons both from the mistakes made and from positive experiences. The development of the LEADER program, its current form, had several antecedents, it was practically the result of a complex development, so the LEADER programme has undergone a number of changes and we believe that these changes have had many benefits in terms of improving the living conditions of rural people, but that the system has yet to achieve real community-building effects. We have therefore compiled a selection of the most important events and developments in the LEADER programme, with the intention of highlighting the key achievements that have been made. We would like to take stock of the less successful activities and operational anomalies whose continuation does not help the already problem-free process of community building and rural development. In many cases, unfortunately, programmes have been implemented not to build community but to serve individual interests.

Rural development, leader program, regional and integrated development of hungary, transformation, support

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149141102

IDR: 149141102 | УДК: 338.43 | DOI: 10.15688/re.volsu.2022.3.9

Текст научной статьи Leader program: development potential for rural life improvement

DOI:

If we want to get to grips with the idea of rural development based on Community initiatives, we have to start from the basic situation that rural areas are in a difficult situation, namely that the countryside has lost its basic functions. Our analysis is therefore based on the diagnosis that has characterised rural areas in general for decades. These are: depopulation and ageing, the loss of agricultural labour, rural incomes below the central European average, and the lack of some basic infrastructure, but all this, together with the socio-economic backwardness of the countryside, is accompanied by positive elements such as a cultural and environmental wealth which, if well exploited, can diversify the activities of the area.

Grass-roots initiatives are increasingly being discussed as a solution to these problems. In rural areas, many see tourism as a socially valorised territorial resource as a starting point for such initiatives, which can help to improve economic and social problems [Wachtler, 2003]. Similarly, it is often argued that tourism or agriculture as drivers of local economic development in rural areas can often be presented as a break-out option, a tool or a complex solution, but that this is generally not sufficiently established in the individual areas and that one sector alone is rarely able to solve the socio-economic problems of rural areas. This is also problematic because sectorspecific solutions carry serious risks, as exposure to the sector and the difficulties it may face can lead to “local disasters” (e.g. serious economic problems caused by the crown virus in tourismbased areas). We agree with Hanus, who believes that tourism, as an important element of economic diversity and rural development, can contribute to economic catch-up, the conservation and sustainable use of natural and other resources, and the improvement of the quality of life of local people [Hanusz, 2008]. It is therefore necessary to adopt a conditionality approach and to learn that there is no single solution, that individual solutions can always work, taking into account and building on local specificities. It is therefore of the utmost importance to be aware of the different characteristics of a given area, as some sectoral developments require certain preconditions that are not sufficiently present in all rural areas [Dávid et al., 2007].

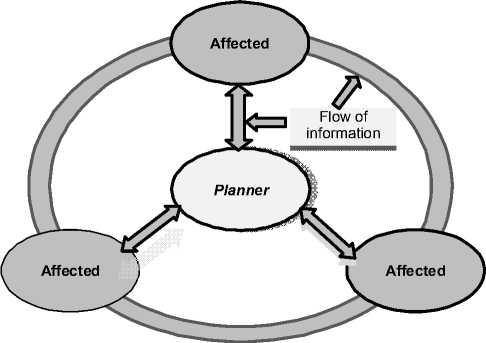

The solution could be the so-called “un” (see fig. 1). Its key element is the activation of local actors, the joint development of a vision. Community planning involves the active participation of stakeholders from the very beginning of the planning process. It is an opportunity for them to get to know each other, to share their ideas and the core values they wish to uphold. It can be seen that, compared to expert planning, there is a much higher level of engagement and active participation. The socialisation of the plan resulting from the collective reflection is quite easy, since it is created by consensus and accepted by the community [Szaló, 2010].

Material and method

During the preparation of the study, we synthesized the related literature and professional opinions, as there are relatively large differences in interpretation and application of the topic, both among experts and among the organizations, local governments, NGOs and groups involved in the practical application.

Our basic objective was to summarise the literature that is essential for a more detailed analysis of the knowledge identified as the subject of our study, namely a brief summary of the theoretical approach and practical implementation of LEADER initiatives and of national and international experiences.

Fig. 1. Internal community planning scheme

Note. Source. Edited by the Authors, based on [Tóth, Oláh, 2012].

In this study we have systematically listed the main milestones and milestones of the LEADER approach, tried to explore the processes and events that have led to the current situation and, with a view to the future, collected suggestions for observations that could lead to improvements in the programme.

The emergence of rural development policy in the European Union

The fact is that the countryside has real values, but these values are under threat. There are many unresolved problems (ageing population, migration, unskilled youth, unemployment), so new methods, experiments, grassroots Community initiatives are needed and should be supported and well integrated. In rural areas in Hungary, there is a need for cooperation that is close, lasting and based on economic interests. A given rural community can only be successful if it relies on its own resources, skills and economic potential, and does not expect others to improve its lot.

Europe in the 1950s was still recovering from the Second World War. The main concerns of the European states were reconstruction and the restarting of industry and agriculture, including the organisation of a secure food supply for the population. This was partly the reason why one of the main objectives of the emerging European Economic Community was the creation of a common agricultural policy. According to Article 39 of the Treaty of Rome, The aim of the common agricultural policy (CAP) shall be: to increase the productivity of agriculture by improving technical progress, rationalising agricultural production and making the best possible use of labour; to ensure an adequate standard of living for the agricultural population, in particular by increasing the per capita income of the agricultural community; stabilising the market; secure supplies; ensure that consumers are supplied at a fair price.

Rural development policy in the European Union was first introduced in the AGENDA 2000 package of measures, based on multifunctional agriculture and wider support for rural society. The question is: why was a new rural development policy needed?

The answer can be found in a study on the CAP reform:

– because it is important for a healthy agricultural sector;

– because it is important for maintaining a living environment and quality of life, which the countryside has a vital role to play in shaping;

– the dynamic economic development of the Union requires social and economic cohesion.

Here we would like to note that, in our opinion, Hungary needed and still needs a rural development policy, regardless of its accession to the European Union. Why because regional tensions in the countryside, as well as the prevention of migration and the maintenance of innovative activities, can be effectively addressed through rural development policy. However, the successful rural development policy in the European Union is an instructive example to follow.

The creation of the Rural Development Regulation was a significant step forward for the European legislative order. The Community Initiatives funded by the European Union in the period 2000– 2006 were programmes that required a grassroots, local initiative to be implemented (INTERREG, EQUAL, URBAN, LEADER).

The birth and development of LEADER

Rural areas in the EU are very different, not only in terms of environmental protection, economic development, social, cultural, political and institutional differences, but also in terms of development dynamics.

Rural areas face many problems:

-

1. A low population, an ageing population and an uneven demographic structure.

-

2. A lack of qualified young people and a growing number of disadvantaged people.

-

3. A strong agricultural sector, pressure from nearby urban areas.

-

4. Wide income disparities and increasing isolation.

-

5. A growing gap between the business sector and the civil sector.

Their marginalisation is exacerbated by population decline and lower income levels compared to cities. All this has led to the need for new development methods and initiatives, community interventions for complex rural development. This is why the EU Commission launched one of the most important Community initiatives, LEADER, in 1991. The acronym stands for the French name of the programme (Liason Entre Action pur le Development de Economie Rurale).

LEADER I and LEADER II. The programme was launched as LEADER I on a pilot basis in 1991– 1993 with a budget of ECU 400 million. The Community Initiatives were financed by the Structural Funds. A significant change in the programme is that from 2000 it is possible for an action group to cooperate with an EU action group and an action group from outside the Member State. This is the third period of LEADER.

LEADER+. The success of the LEADER programme is demonstrated by the fact that the programme has been funded by the European Union for the third period (2000–2006). The development of rural areas has gradually become key, requiring experimentation and the search for innovative solutions.

Learning about the LEADER programme gives you the conviction that you can get EU support for almost anything that the programme’s creators can make you believe is in the interest of a region, or for the benefit of the communities living in the region, or for the production of value. The LEADER method has implemented an experimental and integrated scheme for rural economic development. It was based on embracing local, grassroots initiatives because only local communities know the resources, potential and constraints of their own rural areas. The LEADER+ programme started from the perspective of sustainable development, which was defined at the 1992 Rio de Janeiro Summit as a way of development that aims to – meet the needs of the present without preventing future generations from achieving their own. It therefore seeks to take into account the internal opportunities and constraints of an area, its cultural, economic, social and environmental achievements, as well as the external opportunities and constraints that arise when different local economic enterprises emerge. Changes in rural development policy have continued into the next planning period (Fig 2.).

Fig. 2. The 7 key features of LEADER

Note. Source: Edited by the Authors, based on [Eperjes, 2013].

Rural development policy 2007–2013

The European Union’s new rural development policy was established and announced by Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005. This rural development policy also recommended a series of measures from which Member States could choose which to include in their integrated rural development programmes and request financial support from the Community.

The policy has continued to focus on the sustainable development of rural areas, and to this end has focused on three main policy objectives, as agreed: improving the competitiveness of agriculture and forestry; promoting land use and improving the quality of the environment; and improving the quality of life and encouraging diversification of economic activity.

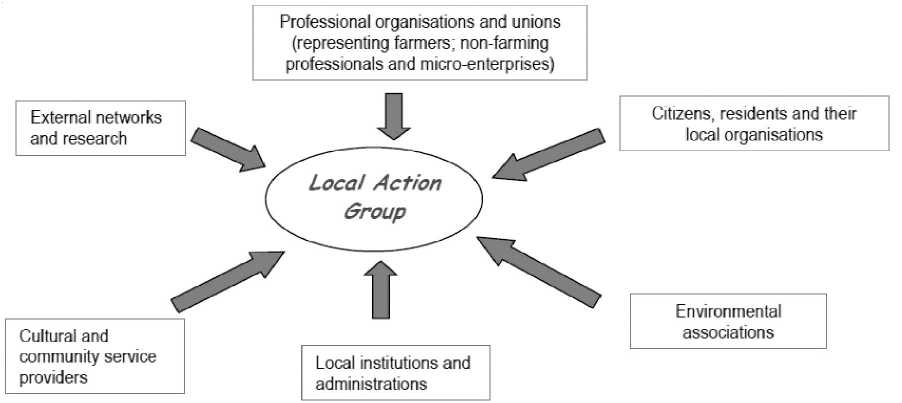

The three policy objectives above form the thematic strands of the rural development programmes, which are linked by the LEADER axis as the “methodological” axis (Fig. 3).

LEADER has implemented its projects by bringing people together in rural areas. LEADER – a community can be made up of several adjacent municipalities in a coherent area. A Local Action Group (LAG) (made up of participating municipalities, local businesses and NGOs) draws up a development strategy for the area with the involvement of local people. The national institution decides on the amount of money available to the Action Group, which is then allocated to the final beneficiaries (i.e. the applicant organisations, institutions, businesses, etc.) through a regional call for proposals.

A new paradigm has emerged as a transition in the principles of the EU 2014–2020 programming period (which are an integral part of the established Europe 2020 strategy), the localisation theory of sustainability, which, combined with the new EU framework legislation, offers a number of opportunities for innovation for Member States. The key pillars of the EU’s integrated territorial (local development) policy are multi-funding (planning across several funding funds to increase efficiency); the extension of the LEADER concept; the use of different funds by LAGs; the emergence of integrated approaches to cross-sectoral development; and more detailed local identification of problems and more effective interventions. One of these innovations is the introduction of new instruments for a spatially based approach, such as Community Led Local Development (CLLD). The approach of this old-new instrument builds fully on the previous LEADER [Eperjes, 2013; Eisenburger, 2014]. According to the EU Council press release of 2 December 2021, The Council has decided to adopt a fairer, greener and more performance-based agricultural policy for the period 2023–2027, with the following specific objectives, which have been discussed on several occasions.

For the Rural Development Programme, the resources for the 2014–2020 period are HUF 1413.18 billion under Government Decision 1152/2020, which can be cleared until 31 December 2023. Under Regulation (EU) 2020/2022 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Hungary will receive transitional funding from the European Agricultural

Rural Development Policy 20072013: Architecture

Rural Development 2007-2013

Axis 1 Competi -tiveness

Axis 3 Economic Diver.

Axis 2 Environment

Land Management

Quality of Life

Single set of programming, financing, monitoring, auditing rules

Single Rural Development Fund (EAFRD)

Fig. 3. The architecture of the European Union’s rural development policy 2007–2013

Note. Source: Edited by the Authors, based on [FVM, 2006].

Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) for two more years (2021 and 2022), with the Government providing for 80% domestic co-financing. This will add an additional HUF 1 527.3 billion to the Rural Development Programme (RDP) envelope, which will be settled by 31 December 2025. This means that the total amount available for the Rural Development Programme over the period 2014–2022 will increase to HUF 2941.1 billion.

The changes to the CAP, and therefore to the new LEADER-related system that is currently due to start in 2023, are constantly being reported, showing that the idea is not yet finalised, e.g. at the Agriculture and Fisheries Council in June 2021, EU agriculture ministers confirmed the provisional agreement with the European Parliament on the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (Fig. 4). The new policy: Strengthens Member States’ commitment to social and labour rights of farm workers; Encourages farmers to adopt more environmentally friendly farming practices; Support small farms and younger farmers; Better links support to farm results and performance.

This means that the next step is to agree on the remaining technical elements of the proposed reform at inter-institutional level, and then formally approve the proposal by the European Parliament and the Council. According to press reports, at the Council meeting in March 2022, the Commission informed ministers of the state of play of its assessment of the strategic plans under the future CAP. So the process is not yet complete.

The seven key aspects of the LEADER method, developed in 1991, define the current LEADER approach to implementation. The CLLD is a method based on dialogue and participation, and requires a complex and coherent structure for planners to design and implement a successful Local Development Strategy (LDS). Its application aims to ensure the development of the territory by strengthening the participation, commitment and cooperation of local actors and by creatively mobilising internal resources [European Committee, 2014].

The CLLD focuses on sub regional areas, i.e. the integrated and sustainable development of rural areas and urban areas and neighbourhoods. This means that the LEADER concept of rural areas will be translated into urban areas. Urban spaces that meet the criteria can therefore also be the setting for grassroots development strategies, designed by local communities, and in which local decisions on the use of resources are taken. Whereas previously only a part of the EAFRD funds could be used for CLLD-based strategies, the Regulation laying down common rules for the operation of the different funds allows for the allocation of resources from several funds for the implementation of LDS [European Committee, 2014; Czéghér, 2013]. This is why it was important in 2015 for LAG to take into account and plan with the measures and sub-programmes of other Rural Development Programmes relevant to the strategy, as well as with the possibilities of other Operational Programmes and other development programmes when planning the LDS [Áldorfai, 2021].

Fig. 4. Specific objectives of the new CAP

Note. Source. Edited by the Authors, based on [Az új közös ... , 2022].

One of the strategic principles of the LEADER approach is innovation, i.e. that problems or opportunities can be addressed not only by applying previous solutions, but also by new methods, since there is no general recipe for success, so we have to develop new methods until we have uniformized every single element of the space. This will never happen and should not be the aim of any development in the context of space. The ball is currently in the European Commission’s court, as a uniform methodology for the design and implementation of community-led local development is not yet available [Áldorfai, Topa, Káposzta, 2015; Nemzeti LEADER kézikönyv, 2015].

We agree with György Áldorfai’s opinion, as he believes that it has become necessary to develop a methodological approach that combines dynamic and static analyses to detect changes in the spatial resources of a given cycle. Of course, some of these changes are the result of social, market and globalisation processes, but others are the result of development, which can stabilise or change the external effects of the aforementioned processes [Áldorfai, 2021]. He has developed his method, but unfortunately, to our knowledge, it has not yet been applied in practice.

In the period 2014–2020, the development of small-scale infrastructure and basic services in rural areas will be addressed by sub-measures M07 (Basic services and village renewal) and M19 (LEADER local development) of the Rural Development Programme of Hungary, which are part of priority area 6B (Promotion of local development in rural areas). Measure M07 supports the development of rural infrastructure and basic services through smallscale improvements to built infrastructure in rural settlements (7.2) and the extension and improvement of the range and quality of services available (7.4).

Список литературы Leader program: development potential for rural life improvement

- Áldorfai Gy., 2021. Magyarország térbeli teljesítményértékelése: PhD. értekezés. URL: https://archive.uni-mate.hu/sites/default/files/aldorfai_gyorgy_tezis.pdf

- Áldorfai Gy., Topa Z., Káposzta J., 2015. The Planning of the Hungarián Local Development Strategies by Using Clld Approach. Acta Avada, no. 2, pp. 13-22.

- Az új közös agrárpolitika legfontosabb szakpolitikai célkitűzései, 2022. Europa.Eu. URL: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/keypolicies/common-agricultural-policy/new-cap-2023-27/key-policy-objectives-new-cap_hu (accessed 5 February 2022).

- Czéghér I., 2013. A 2014–2020-as fejlesztési időszak uniós forrásainak tervezése. URL: http://www.szpi.hu/download/oszi-konferenciasorozat/2013/A-2014-2020-as-fejlesztesi-idoszak-unios-forrasainaktervezese.pdf (accessed 23 January 2021).

- Dávid L., Tóth G., Kelemen N., Kincses A., 2007. A vidéki turizmus szerepe az Észak-Magyarország Régióban, különös tekintettel a vidékfejlesztésre a 2007-13. Évi agrárés vidékpolitika tükrében. Gazdálkodás – Agrárökonómiai Tudományos Folyóirat, no. 51 (4), pp. 38-57.

- Eisenburger J., 2014. A Guide to the European Union Funding Funds. URL: http://www.greens-efa.eu/fileadmin/dam/Documents/Publications/2014_2020_UTMUTATO_AZ_EUROPAI_UNIO_FINANSZIROZASI_ALAPJAIHOZ_.pdf (accessed 15 March 2021).

- Eperjes T., 2013. Helyi gazdaságfejlesztési lehetőségek a LEADER Program keretében és a 2014-20-as programozásban. URL: http://docplayer.hu/3650053-Helyi-gazdasagfejlesztesi-lehetisegek-aleader-program-kereteben-es-a-2014-2020-asprogramozasban.html (accessed 15 March 2022).

- European Committee 2014 Community-Led Local Development, 2014. URL: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/community_hu.pdf (accessed 11 March 2022).

- FVM, 2006. URL: https://www.agraroldal.hu/2006-fvmrendelet-a-szolo-szaporitoanyagok-eloallitasarolrendelet.html (accessed 22 February 2022).

- Hanusz Á., 2008. Turisztikai programok, mint a vidékfejlesztés lehetséges eszközei Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg megyében. Hanusc Á., szerk. A turizmus szerepe a kistérségek és a régiók gazdasági felzárkóztatásában. Nyíregyháza, s. n., pp. 63-79.

- Nemzeti LEADER kézikönyv, 2015. Lechner Nonprofit Kft. URL: http://gis.lechnerkozpont.hu/leader/HFS_ tervezesi_utmutato_1007.pdf (accessed 23 February 2022).

- Nemes G., Magócs K., 2020. A közösségi alapú vidékfejlesztés Magyarországon A LEADERintézkedés eredményei a 2014–2020-as tervezési időszak félidejében, Gazdálkodás. Gazdálkodás, 64. évfolyam 5. szám. URL: http://www.gazdalkodas.hu/index.php?p=cikk&cikk_id=1332 (accessed 22 February 2022).

- Ritter K., 2019. A vidékbiztonság vidékgazdasági alapjai. Budapest: Nemzeti Közszolgálati Egyetem Közigazgatási. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12944/15949 (accessed 27 March 2022).

- Szaló P., 2010. Területfejlesztési füzetek 1. Segédlet a közösségi tervezéshez. Budapest, s. n. 93 p. URL: http://www.terport.hu/webfm_send/279 (accessed 20 March 2022).

- Tóth T., Oláh I., 2012. A közösségi tervezés elméleti és gyakorlati alapjai. Far kas A., Kollár C., Laurinyecz Á., szerk. A filozófia párbeszéde a tudományokkal: A 70 éves Tóth Tamás professzor köszöntése. Budapest, Protokollár Tanácsadó Iroda, pp. 358-370.

- Wachtler I., 2003. Falusi turizmus. Magda S., Marselek S., szerk., Észak-Magyarország agrárfejlesztéseinek lehetőségei. Gyöngyös, Agroinform Kiadó, pp. 189-200.