Луи Каравак и секуляризация русского искусства

Бесплатный доступ

В статье исследуется творчество Луи Каравака (живопись портретного жанра и произведения декоративно-прикладного искусства, созданные для украшения православных храмов) на предмет соотношения в них светского и религиозного. Автор высоко оценивает роль живописи Каравака, его педагогической работы и религиозной позиции в процессах секуляризации русского искусства. Светское начало в творчестве художника рассматривается в контексте развития западноевропейской культуры. В свете новых данных о личности живописца автор выясняет, насколько его творческий путь был связан с религиозной жизнью. Исследование показало, что в творчестве Каравака были применены разные способы к обмирщению живописи: соединение священных христианских образов с мифологическими образами-символами и превращение их в универсальное внецерковное культурное наследие, обращение к эротическим мотивам, очищение живописных композиций от религиозных смыслов («размывание» и даже полное устранение их религиозного содержания). Автор делает вывод о том, что эстетика рокайля полностью соответствовала моральным и религиозным принципам Каравака.

Людовик каравак, рококо, искусство xviii в, религия в искусстве, секуляризация искусства и культуры

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147151211

IDR: 147151211 | УДК: 75.03 | DOI: 10.14529/ssh170409

Текст научной статьи Луи Каравак и секуляризация русского искусства

The name of Alexander Mezenets can be met in the first works on the history of the Russian medieval culture of written music. It became known due to the acrostic (“Elaborated by Alexander Mezenets and others”), which is closing the “The Notice… to those wishing to study chant singing” [1, p. 208—209]1. As we know, the preface to this work dwells upon the calling of two Moscow commissions to revise “razdelnorechie” chant books2. That is why Mezenets came into history primarily as one of the commission participants and the author or one of the authors of The Notice . The range of sources on the life and activities of the didascalos has eventually been enlarged. Everything related to the name of Alexander Mezenets — documents, manuscripts and especially autographs — have always attracted researchers.

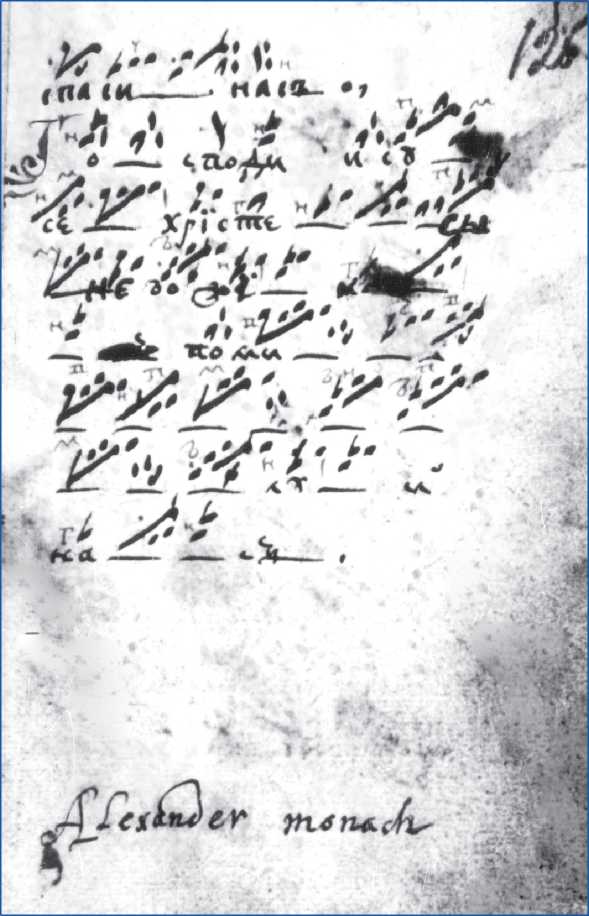

In a newspaper article dated by 1863 Peter A. Bessonov claimed, that he “has received from V. Borisov a big and excellent manuscript verses book of the 17th century, all in kryuki (Russian musical neumes, so-named znamenny ones)” [2, p. 20]. The next year, the author of the article published more detailed information on the book: it was a collection, containing “Pokayanny na osm’ glasov slezny i umilitelny” (“Penitential stichera for eight echos — lacrimal and pathetic”). On the margins of some pages alongside with kryuk “additions” Bessonov discove red some notes in Latin alphabet:

“Alexander monach”, “Alexander monach Mezenec”, “Monach Alexander pracewal dobre. Mapa”. Considering these notes to be made by the “famous figure of the mid 17th century” Alexander Mezenets, the researcher assumed, that the master was educated in the schools of South-Western Russia, and that “it seems the text (of the manuscript — N. P. ) was written by the same person, whom the margin additions are attributed to” [3, p. VIII]; later on he directly called this manuscript Mezenets’ “autographic” creation [4, p. 53].

In 1883 the treatise by Ivan D. Mansvetov “How the church books were revised” came out, which was executed “using the documents from the archive of the Moscow Printing house library”. For the first time ever, this book mentioned documents (expenditure books of the Printing Office ( Prikaz knigopechatnogo dela ) containing information about the participants of the Second Moscow commission on chant books revision [9, p. 4 etc.]. Soon on the ground of same documents Dmitry V. Razumovsky published the names of all six members of this commission and their autographs; didascalos Alexander Mezenets became known as the “elder of Savva monastery in Zvenigorod” [11, p. 50].

Earlier in June 1880, Alexey E. Viktorov made up a description of manuscripts of the Nil Stolbenskiy Monastery. Among the chant books there was one, which was contributed in 1667 by the duke Yu. S. Urusov. The manuscript was prefaced with the verses containing some biographical information on Mezenets and a note “Monach Alexander Stremmouchow”. In 1890 Viktorov’s work was published with some notes and the full text of the verses [23, p. 201—202].

In 1899, while making an overview of chant manuscripts collected by the Moscow Synodal chant school, Stepan V. Smolensky pointed at the “autographic sample by the famous theorist, elder Alexander Mezenets (№ 98, 1677)” [20, p. 60]. In the manuscript he also found an “autobiographic verse” by the master, which the scholar published later on in his next work [19, p. 35—36]. In the latter treatise he also reported about another chant manuscript from the same collection

(№ 728). The previously described book from the Nil Stolbensky Monastery library is easily recognizable in this historic document by the notes and verses contained in it. When publishing verses from this manuscript once more (after Viktorov), Smolensky expressed his doubts that “this is hardly an autobiographic verse by Alexander Mezenets”: the two manuscripts were written in a different hand style, and the researcher failed to find the system of signs ( priznaki ) in the neumatic notation to the second manuscript, which could be elaborated only by this master. However, he proved the autobiographic authenticity of the first book using the records of it being sold four years later by the person who was presented with it by Mezenets himself [19, p. 36]1.

The scholars, who afterwards were dealing with the outstanding personality of the didascalos and citing his biography, primarily relied on the above-listed publications [for example: 5, p. 329]2.

As far as the previously mentioned expenditure books of the Printing Office, containing Mezenets’s

“Pokayanny na osm’ glasov”. XVII century. Alexander Mezents’s kryuk (musical neumes) and shorthand (cursive) letter [12, fol. 125]

signature for payments to, were introduced into circulation among the scholars, there was appeared an opportunity to compare the manuscripts attributed to the master with these books. This enabled to determine which of those manuscripts are autographic and to settle the authenticity problem concerning the biographic information on the didascalos, which was contained in the verses. Such overall study of the sources has never been carried out. The difficulty of the research lies in the fact that Mezenets used shorthand when putting records in the documents and half-running hand when creating manuscripts.

The book of penitential stichera mentioned in the treatises of Mansvetov, was found in the Manuscript Collection of RGADA3. Thanks to the fact, that the creation of this book took quite a time (probably the scribe worked on it occasionally and under different circumstances), its text contains peculiarities, which could be used as the starting point of our research. For instance, the chant at fol. 125 was probably inserted

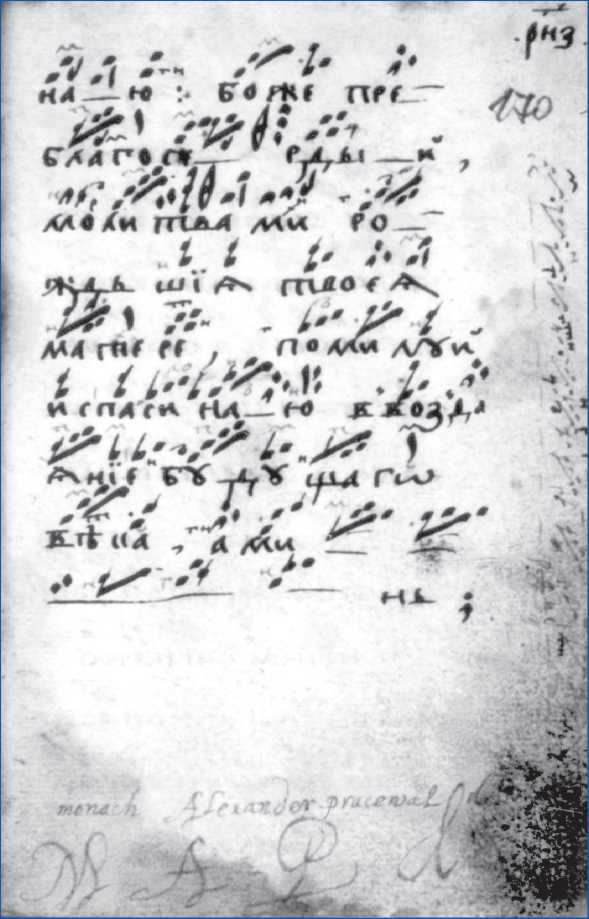

“Pokayanny na osm’ glasov”. XVII century.

Alexander Mezents’s kryuk (musical neumes) and half-running hand (semi-uncial) letter [12, fol. 170]

somewhat later than the others. It is written in shorthand and in the same hand style and ink as the shorthanded remark “Alexander monach” left at the same page. Many cinnabar inserts in the margins — variants of the lines, neumatic formulae ( fitas) or complex znamenny neumes, the whole chant (fol. 66, back side) — are also written in shorthand. All these, including the records in Latin alphabet, should be first of all compared to Mezenets’ signatures in the book of expenditures of the Printing Office ( Prikaz ). The comparison shows that the same person made all records. The fol. 158—170 in the manuscript Pokayanny [12] are most prominent — they contain verses written in the shorthanded half-running hand 1. Upon comparing the shorthand of Mezenets with this written piece we come to the conclusion that the latter was also created by the master. Besides, fol. 170 states: “Monach Alexander pracewal dobre. M. A. P. d.”2. Finally, when we have identified the shorthanded halfrunning hand as belonging to Mezenets, we can compare it to the half-running hand of the rest of the manuscript Pokayanny [12]. One and the same person writes both pieces. Kryuk ( Znamenny notation) text of the book is produced by one hand. The outline of neumes in all the parts of the book (including inserts and explanations ( razvods ) in the margins, additional chants written in shorthand) is unified having an identical slant. The same is true for the cinnabar signs. Pagination is done by one hand, as well, and the hand style and ink in it change in accordance with the changes in the body text. Consequently, the book Pokayanny [12] was entirely written by one scribe — the outstanding master of the chanting art and didascalos Alexander Mezenets3.

The manuscript from the library of Nil Stolbensky Monastery is now stored at GIM4. At the beginning of the book there is an inserted (pasted in) folio with some verses containing the biographical information on Mezenets, with a few lines written in a small halfrunning hand almost like the rest of the manuscript. The fact that the verses and the body text of the book are written by one person becomes obvious when we compare them to the chants, which were apparently included in the book later, but simultaneously with the verses (for example, at fol. 402, back side). The headline at fol. 283 is also written by the same copyist (in some places the titles were written by another scribe): the same half-running hand, the same Greek-style outline of the initials and the capital letter in the word “Alexander” in the verses and in the letters of the word “Stichera” in the headline. Therefore, one scribe created the verses and the major hymnographic texts of book. The comparison of this book with the manuscript Pokayanny [12] makes us come to the conclusion that it is Mezenets who was the copyist. For example, the hand style of the verses in book [8] is absolutely identical to that of the contents (the list of initial lines of the verses with page numbers) in manuscript Pokayanny [12].

In book [8] there are some records made in shorthand, as well. The style of shorthand remarks “Monach Alexander Stremmouchow” and others (fol. 1, back side; 26, back side; 64, back side; 106, back side; 282 back side) is identical to the style of similar remarks in manuscript Pokayanny [12]. Consequently, the records made in Latin alphabet in book were made by Mezenets. At the end of the book there are concluding remarks to the singers (fol. 403). The comparison of the shorthand style of the remarks with Mezenets’ signatures in the expenditure book of the Printing Office ( Prikaz ), as well as with the margin remarks and some chants from manuscript Pokayanny [12] (which were also made in shorthand) allows us to state, that the concluding remarks were written by Alexander Mezenets himself. He also wrote some additional notes in book [8] (for example, the note “In Great chant” ( “Bol’shim rospevom” ) in the margin of fol. 402, back side).

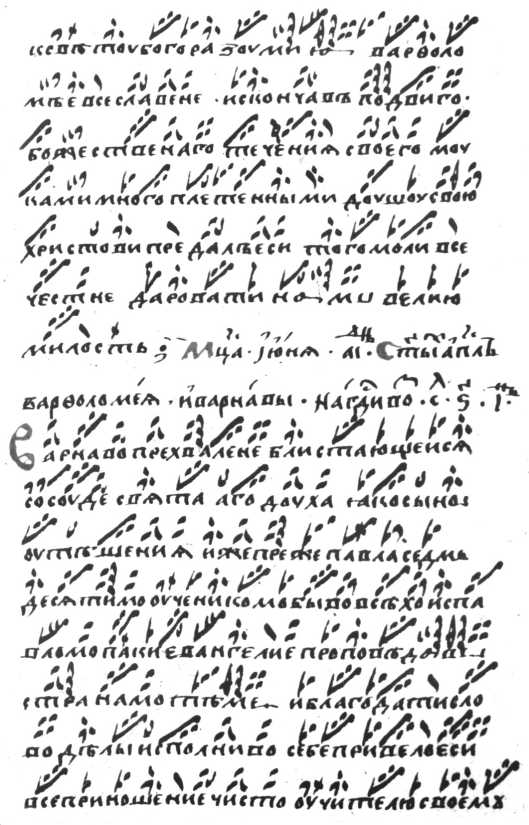

Kryuk book. 1666. Alexander Mezenets’.

Verses [8, fol. 1, back side]

As far as the kryuk (znamenny neumatic) text is concerned, it was also created by one copyist, including some chants, written in shorthanded half-running style. The comparison of neumes and signs outlines to the neumatic texts from book Pokayanny [12] shows that they were also written by Mezenets.

As we see, manuscript [8] is created by Alexander Mezenets almost single-handedly. However, there are some pieces of writing in it, which could not be attributed to this outstanding didascalos. The cinnabar titles and initials might have been inserted in the book by another copyist (he missed out the headline before the Stichera evangelical (fol. 283) and it was written by

Kryuk book. 1666. Alexander Mezenets’. Heirmologion [8, fol. 2]

Mezenets himself). The titles are made with the use of ornamental script and elegant shorthand (fol. 2, 170), which differs greatly from Mezenets’ shorthand. The initials of the second copyist also vary from the didas-calos’s initials, which the former left in chants or added somewhat later to the basic text, and in the concluding remarks to the singers. The second copyist’s style could be traced in the record mentioning Duke Iury Urusov’s contribution. The verses inform that the book was created “in the house” of Duke Urusov, which allows for the suggestion that this copyist was a duke’s “domestic” one. Probably he or any other of the duke masters drew the miniatures in the book.

S. V. Smolensky’s doubts regarding the autobiographic character of the information contained in the verses of this manuscript are groundless. The researcher reasoned his doubts by the specific signs ( priznaki ) which were absent in the neumatic notation of the book, which, in his opinion, “due to the date of the verses (1666) contradicts the direction of Mezenets’ reformative activity” [19, p. 36]. Firstly, as we have proved, the verses were written by the master himself. Secondly, on the scrupulous examination one can easily see the priznaki in manuscript [8]. At the beginning of the book, in Heir-mologion ( Irmologiy ) they are quite rare, then are more numerous (fol. 54, 97, back side, etc.) and starting from the Octoechos (fol. 170) the signs are met throughout the whole text. Thirdly, the system of signs was finally settled and introduced in general use by the Second Moscow Commission, which was completing the chanting art reform together with Alexander Mezenets.

After the book of corrected istinnorechie (“true language”) chants was accomplished, Mezenets prob- ably made a final revision of the kryuk text using cinnabar. Upon completion, the master left his Latin signatures after some chapters of the book, wrote verses and concluding remarks at the end of the book1. From our point of view, that was the process of working at manuscript [8].

The third manuscript related to the name of Mezenets and considered his “autographic specimen” by Smolensky is also stored at GIM2. The styles of three scribes could be singled out in this manuscript. The first one is the copyist of the basic text of the book — the Menaia. The comparison of his style (half-running hand, neumes, signs) with the style of manuscripts [8; 12] authored by Mezenets demonstrates, that manuscript [7] is not didascalos’s autographic creation3. The second copyist inserted a page (fol. 1) with verses, which among other things mentioned that this book was Mezenets’ present to his apprentice — podyachy (minor clerk) of Yam-skoy prikaz (Mail office) Pavel Chernitsyn. The same copyist (whose occupation was rather connected with clerical duties than with writing books) made a record mentioning the selling of the book by Chernitsyn in 1681. Therefore, Chernitsyn could most likely rewrite the verses composed by Mezenets. It was also he, who made cinnabar explanations ( razvods ) of complicated neumes ( znamyas ) in the margins and some corrections in the text (for instance, fol. 9, 17, 21, 32 etc.). Finally, the third copyist authored the small final part of the manuscript — Trezvon , a book of minor and mid church festive services chants (fol. 125—144), that was bound to the Menaia later (which is proved by the filigree). The style of half-running hand and kryuk pieces of this copyist are identical to Mezenets’.

To sum everything up, the detailed analysis of the manuscripts, which were related to the name of the outstanding music theorist of the 17th century as early as in pre-revolutionary historiography, showed that only two of them [8; 12] were in full written by Alexander Mezenets; in the third manuscript [7] only a few inserted chapters were created by the master. Consequently, the authenticity of the information about Mezenets, which is conveyed in the verses prefacing book [8] and written by the master himself, raises no doubts. In our opinion, the details about the master mentioned in the verses of manuscript [7] are quite trustworthy as well, though they were not written by Mezenets himself. The book was given by the didascalos to one of his apprentices as a present and this fact was recorded in a fashionable form of verses; however it was the apprentice (Pavel Chernitsyn) who rewrote the verses on a single page and inserted it into the book. He was unlikely to have some reasons to make any changes in the verses, let alone his teacher’s biography. It should be pointed out that the contents of manuscripts [7; 8] do not contradict each other and are very close stylistically, compositionally and verbally. Therefore, both verses could be considered Mezenets’ autobiographic creations.

As we have already noted, during his correction work in the Second Moscow Commission (1669—1670) the outstanding didascalos Alexander Mezenets was the elder of Savva-Storozhevsky monastery in Zvenigorod. The nine kryuk [znamenny neumatic] books from the library of this monastery, which have survived till the present day and are now stored at RGADA, in the Manuscript Collection of Synodal Printing House (F. 381), could not but draw our attention. Their analysis has shown that Mezenets participated in the writing of six of them.

Let us focus on five books [14—18], which were apparently written in the second half of the 1640s — early 1650s. These manuscripts are unified not only by Mezenets’ hand style, but also by the hand style of the second major copyist (the rest hand styles are randomly seen). His hand style is easily recognizable — a distinctive shorthanded half-running style with a quite distinctive outline of Znamenny neumes. In manuscripts there are records of these books contributed to the “Storozhevsky monastery” by the elder Feodosy Panov on January 30, 1653 [15, fol. 1—13; 16, fol. 8—28; 17, fol. 230; 18, fol. 1—15.]1. Such record is missing in the one manuscript [14]. Probably it was lost. However, a certain Misail, who apparently was a monastery treasurer, put a remark in all the books that on February 24, 1659 “with the blessing” of Storozhenvsky archimandrite Nikonor they (books) have been given to the “cathedral church choir masters” [14, f. 420; 15, fol. 552; 16, fol. 766; 17, fol. 231; 18, fol. 521). Due to the fact that the above-mentioned second hand style could be seen only in the elder Panov’s manuscripts, we can justifiably assume that it belongs to the elder himself. If it is true, than Panov was a brilliant expert and an authority in the field of chant art. Obviously, he was the teacher of Mezenets and some other monastery kliros (choir) singers, which is proved by his multiple corrections and inserts of kryuk pieces into the pages written by other copyists, including Alexander Mezenets.

The first manuscript is a book composed on Octoechos, theoretical musical guide — Fitnik , and selected chants 2. Mezenets’ hand style is the fourth in

Collection of chants. 40s — 50s of the XVII century. Alexander Mezents’s kryuk (musical neumes) and half-running hand (semi-uncial) letter [14, fol. 381]

this book. It is a fine, even and delicate (semi-uncial) letter. The “wise lines” from the stichera in honour of Ivan Suzdalsky and Alexander Nevsky are written in this hand style, as well as a number of doxasticons.

The next chant books [15; 16] are, respectively, the second and first part of the Sticheron Book “for the whole year”; in the inserted records they are called “ Trezvony ” (minor and mid festive services). Each part contains chants appointed for three months3. In manuscript [15], the master wrote the list of contents4, prayers of worship of Vsevolod Pskovsky (fol. 475)

and Sergiy Radonezhsky (fol. 548, back side), the preChristmas troparion “ Napisashasya inogda ” (Written sometimes) (fol. 551) and the titles to all prayer chapters. In manuscript [16], Mezenets also wrote the list of contents and titles, but far more prayers of worship, many of which are authored by the Russian hymnographers and chant composers in honour of Russian feasts and saints 1. Mezenets is one of the major copyists of this manuscript.

However the master’s contribution in manuscript (which is called “ Tsari-Stikhi ” (“Tsar verses”) in an inserted record) is quite different2. The whole book is written and obviously compiled by Feodosy Panov; only a few subtitles are written by a half-running hand of Mezenets.

The fifth manuscript comprises Triodia, Octoechos and several chants3. Its beginning — Triodion of the Lent till the Passion Week (fol. 1-85, back side) — was written by Alexander Mezenets. The master also wrote the first page before the chapter Triodia stichera of the Passion week and the first chant “From now on” (“ Ot veka denese ” — fol. 181). The major copyist of this book was also Panov.

Finally, one more chant book, connected with the name of Mezenets, is manuscript Obikhod and the Feasts 4. As the records prove, the book came to the monastery library “from the lumber of senior choir singer, hierodeacon Iakov” (fol. 2—21, 307, back side). The main text of the book is written in one (the first) hand style, which has no repetitions in other books. Probably, the copyist was the senior choir singer Iakov himself. Mezenets wrote the titles in the Feasts chapter (fol. 159, 170, 180 etc.) and the last section in Stolp neumes notation which contains “Zadostoyniki putnye” (Festal hymns in Put’ style neumatic notation) (fol. 296—307).

So, the newly discovered Mezenets’ autographs from the Savva-Storozhevsky library (which raise no doubts as such) are records which vary from whole chapters (in five manuscripts) to only cinnabar titles before several chapters (written by another master) — in one manuscript. The half-running hand of the master is definitely the best among the hand styles of Storozhevsky scriptorium copyists, that is why, as we have seen, Mezenets was used to making titles. The autographs of the outstanding theorist of the 17th century as well as those mentioned above are of great value; and the value increases as they alongside some znamenny neumatic manuscripts give a new turn to the research in the field of Russian musical paleography (in particular, concerning the appearance of priznaki ) and provide us with the additional information on the master’s biography. Nikolay Uspensky points to the fact that Mezenets became the elder of this monastery starting from 1668 [22, p. 493]. However the analysis of the extant znamenny neumatic books of the Savva-Storozhevsky library shows that Mezenets participated in their rewriting as early as late 1640s — early 1650s. This brings us to the conclusion that at least two decades earlier than it was supposed up to this moment the master not only lived in Zvenigorod monastery, but was actively involved in the writing of chant books alongside some other monastery copyists (as a rule, they were kliros singers, as well).

Список литературы Луи Каравак и секуляризация русского искусства

- Андреева, Ю. С. Иконостас петербургского Петропавловского собора в свете религиозной жизни Доминико Трезини/Ю. С. Андреева//Вестник ЮУрГУ. Сер.: Социально-гуманитарные науки. -Т. 16. -2016. -№ 3. -С. 91-100.

- Андреева, Ю. С. Католик Луи Каравак: к вопросу о религиозности художника эпохи рококо/Ю. С. Андреева//Вестник ЮУрГУ. Сер.: Социально-гуманитарные науки. -Т. 17. -2017. -№ 3. -С. 15-24.

- Апостолос-Каппадона, Д. Словарь христианского искусства/Д. Апостолос-Каппадона. -Челябинск: Урал LTD, 2000. -266 с.

- Базен, Ж. Барокко и рококо/Жермен Базен. -М.: Слово/Slovo, 2001. -288 с.

- Бенуа, А. Н. История живописи/А. Н. Бенуа. -Т. 4. -М.: Шиповник, 1912. -424 с.

- Бернякович, З. А. Русское художественное серебро XVII -начала XX века в собрании Государственного Эрмитажа/З. А. Бернякович. -Л.: Художник РСФСР, 1977. -288 с.

- Бухгольц, Г. Портрет царевны Елизаветы Петровны в детстве (копия с оригинала Л. Каравака)/Генрих Бухгольц. 1760-1770-е гг. Государственный музей-заповедник «Петергоф».

- Врангель, Н. Н. Иностранцы XVIII в. в России//Н. Н. Врангель. Венок мертвым: худож.-ист. ст. -СПб.: Тип. «Сириус», 1913. -С. 103-175.

- Врангель, Н. Н. Русская женщина в искусстве//Н. Н. Врангель Венок мертвым: худож.-ист. ст. -СПб.: Тип. «Сириус», 1913. -С. 9-25.

- Голлербах, Э. Портретная живопись в России. XVIII век/Э. Голлербах. -М.; П.: Гос. изд-во, 1923. -142 с.

- Государственная Третьяковская галерея. Живопись XVIII -начала XX века (до 1917 г.): каталог. -М.: Изобразительное искусство, 1984. -720 с.

- Громов, Ф. Ю. Бытовой жанр второй половины XVIII в.: русско-французские художественные связи/Ф. Ю. Громов//Вестник Санкт-Петербургского государственного университета культуры и искусств. -2016. -№ 4. -С. 115-118.

- Гроот, Г.-Х. Портрет Елизаветы Петровны в образе Флоры/Георг-Христофор Гроот. 1748-1749 гг. Государственный музей-заповедник «Царское село».

- Даниэль, С. М. Рококо: от Ватто до Фрагонара/С. М. Даниэль. -СПб.: Азбука-классика, 2007. -336 с.

- Евангулова, О. С. Живопись/О. С. Евангулова//Очерки русской культуры XVIII в./под ред. академика Б. А. Рыбакова. -Ч. 4. -М.: Изд-во МГУ, 1990. -С. 111-151.

- Евангулова, О. С. Изобразительное искусство в России в первой четверти XVIII в. Проблемы становления художественных принципов Нового времени/О. С. Евангулова. -М.: Изд-во Моск. ун-та, 1987. -296 с.

- Живов, В. М. Метаморфозы античного язычества в истории русской культуры XVII-XVIII века/В. М. Живов, Б. А. Успенский//В. М. Живов. Разыскания в области истории и предыстории русской культуры. -М.: Языки славянской культуры, 2002. -С. 461-531.

- Записки Якоба Штелина об изящных искусствах в России/состав., пер. с нем., вступ. ст., предисл. и примеч. К. В. Малиновского. -Т. 1. -М.: Искусство, 1990. -448 с.

- Ильина, Т. В. Иван Яковлевич Вишняков. Жизнь и творчество/Т. В. Ильина. -М.: Искусство, 1979. -207 с.

- Ильина, Т. В. Императрица Елизавета в глазах художников русского и западного (начало и конец правления)/Т. В. Ильина//Труды исторического факультета Санкт-Петербургского университета. -2016. -№ 25. -С. 39-46.

- Каравак, Л. Портрет царевича Петра Алексеевича и царевны Натальи Алексеевны в детском возрасте в виде Аполлона и Дианы/Луи Каравак. 1722 г. (?) (Холст, масло, 94×118)//Государственная Третьяковская галерея: сайт. -URL: https://www.tretyakovgallery.ru/ru/collection/_show/image/_id/2547 (дата обращения: 19.05. 2017).

- Каравак, Л. Портрет царевны Елизаветы Петровны в детстве/Луи Каравак. 1716-1717 гг. (Холст, масло, 136×103,5)//Государственный Русский музей. Инв. № Ж-5323.

- Каравак, Л. Портрет цесаревен Анны Петровны и Елизаветы Петровны/Луи Каравак. 1717 г. (Холст, масло, 76×97). Государственный Русский музей.

- Каравак, Л. Портрет царевича Петра Петровича (1715-1719), сына Петра I, в виде Купидона. 1716. (82×67)/Луи Каравак//Государственная Третьяковская галерея. Инв. № 15156.

- Каравак, Л. Портрет царевны Елизаветы Петровны в детстве. Пер. пол. XVIII в. (Холст, масло, 97,5×85,5)/Луи Каравак. Государственный Русский музей. Инв. № Ж-9780.

- Карев, А. А. Портретный образ в контексте русской художественной культуры XVIII века: межвидовые проблемы портрета на рубеже барокко и классицизма: дис. … д-ра искусств./А. А. Карев. -М.: МПГУ, 2000. -318 с.

- Климов, О. Е. Сень над ракой с мощами св. преп. Сергия Радонежского. Архитектурные обмеры и обследование/О. Е. Климов//Архитектурная мастерская Олега Климова: сайт. -URL: http://artklimov.ru/view.php?id=2201 (дата обращения: 03.06. 2017 г.).

- Кожухова, М. В. Европейские наставники русских художников/М. В. Кожухова//История и культура. -2009. -№ 7. -С. 106-117.

- Колмогорова, Е. Е. Семейный портрет в России XVIII века и общеевропейское художественное наследие/Е. Е. Колмогорова//Актуальные проблемы теории и истории искусства. -2016. -№ 6. -С. 543-551.

- Корольков, М. Я. Архитекты Трезины/М. Я. Корольков//Старые годы. -1911. -№ 4. -С. 17-36.

- Маркина, Л. А. Портретист Георг Христоф Гроот и немецкие живописцы в России середины XVIII в./Л. А. Маркина. -М.: Памятники исторической мысли, 1999. -296 с.

- Материалы к словарю русских художников первой половины XVIII века/Н. М. Молева, Э. М. Белютин//Н. М. Молева. Живописных дел мастера: канцелярия от строений и русская живопись первой половины XVIII в. -М.: Искусство, 1965. -С. 185-248.

- Мельник, А. Г. Рака для мощей св. Авраамия Ростовского 1772 года/А. Г. Мельник//История и культура Ростовской земли: материалы конф. 2010 г. -Ростов: Ростовский кремль, 2011. -С. 232-241.

- Мельников, А. П. Нижегородская старина: путеводитель в помощь экскурсантам/А. П. Мельников. -Н. Новгород: Культура, 1992. -53 с.

- Михайлова, А. Ю. Французские художники при русском императорском дворе в первой трети XVIII в.: дис. … канд. искусств. -М., 2003. -240 с.

- Молева, Н. М. Живописных дел мастера: канцелярия от строений и русская живопись первой половины XVIII в./Н. М. Молева, Э. М. Белютин. -М.: Искусство, 1965. -335 с.

- Молчанов, Г. Д. Портрет царевича Петра Петровича в виде Купидона/Григорий Дмитриевич Молчанов. 1772 г. (холст, масло, 53×43). Государственный Русский музей. Инв. № Ж-55.

- Морохин, А. В. Петр I в Нижнем Новгороде в мае 1722 г.: реалии визита и историографические мифы/А. В. Морохин//Уральский исторический вестник. -2013. -№ 3. -С. 84-90.

- Неизв. художник. Портрет Петра Петровича в виде Купидона. Первая пол. XIX в. (с оригинала Л. Каравака). Государственный Эрмитаж. Инв. № ЭРЖ-1817.

- Немилова, И. С. Французская живопись. XVIII век: каталог. Государственный Эрмитаж. Собрание западноевропейской живописи/И. С. Немилова. -Л.: Искусство, 1985. -492 с.

- Нокре, Ж. Аллегорический портрет семьи Людовика XIV/Жан Нокре. 1670 г. (305×420). Версальский дворец. -URL: https://gallerix.ru/pic/_EX/1097720245/719063399.jpeg (дата обращения: 19.05. 2017 г.).

- Петров, П. Н. Каталог исторической выставки портретов лиц XVI-XVIII вв., устроенной Обществом поощрения художников/П. Н. Петров. -2-е изд. -СПб.: Тип. А. Траншеля, 1870. -XXIII, 232 с.

- Поволжье: справочник-путеводитель. -М.: Изд. Волжского гос. речного пароходства, 1929. -56 с.

- Постернак, К. В. Особенности архитектурно-декоративного убранства петербургских барочных иконостасов середины XVIII века (1740-1760-е годы): дис. … канд. искусств./К. В. Постернак. -М., 2014. -203 с.

- РГАДА. Ф. 17. Оп. 1. Д. 266.

- Ростовский Димитрий, святитель. Алфавит духовный. -М.: Сибирская Благозвонница, 2010. -235, с.

- Русское искусство эпохи барокко. Конец XVII -первая половина XVIII в.: каталог выставки. -Л.: Искусство, 1984. -112 с.

- Собко, Н. П. Несколько дополнительных сведений о живописце Людовике Караваке/Н. П. Собко//Исторический вестник. -1882. -Т. 8. -№ 5. -С. 479-480.

- Собко, Н. П. Французские художники в России в XVIII веке. Живописец Людовик Каравак (1716-1752)/Н. П. Собко//Исторический вестник. -1882. -Т. 8. -№ 4. -С. 138-148.

- Татищев, В. Н. Лексикон Российской исторической, географической, политической и гражданской///В. Н. Татищев. Избранные произведения. -Л.: Наука, 1979. -С. 153-327.

- Тютрюмов, Н. Царевич Петр Петрович (1715-1719). Копия с прижизненного портрета работы Л. Каравака/Н. Тютрюмов. Сер. XIX в. (22×16). Государственный Русский музей. Инв. № 6690.

- Успенский, Б. А. Царь и Бог. Семиотические аспекты сакрализации монарха в России/Б. А. Успенский, В. М. Живов//Б. А. Успенский. Избранные труды. -Т. 1 Семиотика истории. Семиотика культуры. -М.: Гнозис, 1994. -С. 110-218.

- Флейгельс, Н. Встреча Марии и Елизаветы (репродукция)/Никола Флейгельс. -URL: http://www.hermitagemuseum. org/wps/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/01.%20Paintings/37657?lng=ru (дата обращения: 19.05. 2017 г.).

- Царевский, А. А. Посошков и его сочинения. Обзор сочинений Посошкова (изданных и неизданных) со стороны их религиозного характера и историко-литературного значения/А. А. Царевский. -М.: Тип. Э. Лисснер и Ю. Роман, 1883. -274 с.

- Чежина, Ю. И. Мифологический портрет в русской живописи XVIII столетия/Ю. И. Чежина//Труды исторического факультета Санкт-Петербургского университета. -2014. -№ 20. -С. 152-160.

- Чирскова, И. М. Власть и культура в России в первой четверти XVIII в.: у истоков культурной политики/И. М. Чирскова//Вестник РГГУ. Серия «История. Филология. Культурология. Востоковедение». -2016. -№ 2. -С. 40-57.