Maneuvering between icebergs: ethnic policy models in Norway

Автор: Ekaterina S. Kotlova

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Economics, political science, society and culture

Статья в выпуске: 21, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Norway is considered one of the countries with a successful ethnic policy towards both indigenous people and migrant groups. The article is devoted to the analysis of the modern ethnic policy model in Norway. Norwegian experience in moderating ethnic interaction seems to be interesting for Russia and its northern and Arctic areas. The author is convinced that modern Norwegian ethnic policy grounded on multiculturalism is in transition towards so-called “diversity model”. Such a transition is caused by the intensification of migration and a threat of radicalization of particular social groups and ideologies.

Hjertelig takk til Signe og Bjørn for herlig selskapet og den fantastiske og inspirerende utsikten fra stuen

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318686

IDR: 148318686 | УДК: 323.1 | DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2015.21.17

Текст научной статьи Maneuvering between icebergs: ethnic policy models in Norway

Until the middle of the 20th century in Norway or abroad no one could think that the ethnic policy would become so relevant. Changes in the Norwegian economy after the WWII made the state able to receive sufficient financial capacity to implement the dreams of its citizens on the stability and prosperity. So that’s how a welfare state was established and the Norwegian social system became attractive for migrants from all over the world. The end of 1970s brought a change to Norwegian policy, especially in regard to the indigenous population — Sami people, whose culture, traditions and identity in the course of centuries, was ignored or oppressed. Such situation could not be called unique. It was a sad tendency of the time, common for many indigenous peoples all over the world. Today, the Norwegian Sami are successfully working on the preservation and development of their culture, and are solving a set of issues of political representation and the rights of the Sami in Norway. In 1989 the Sami Parliament was established to provide greater influence of indigenous people on cultural, social and political issues.

Norwegian experience in solving cultural and ethnic conflicts and moderation of ethnic interaction is useful for Russia to some extent. Both Russia and Norway have been confronting with problems related to indigenous peoples and migrants from Asian countries, in the north as well. Ethnic aspects of Russia's domestic policy are more difficult in view of the fact that our country is more diverse in cultural and ethnical terms. However, the situation in the northern regions has a lot of similarities, especially when it comes to indigenous peoples of the North (IPN), the preservation and development of their culture. Regarding migrants, Norway has accumulated decades of experience and it has established an integration policy of people with different cultural and religious background. It seems to be extremely relevant for Russia in term of development of its northern territories.

The article is focused on the model of Norwegian ethnic policy in its relation to indigenous and migrant groups. Discussing the ethnic policy models it is also important to analyze the circumstances that changed the government policy and the effectiveness of political responses in terms of moderation of ethnic tension. Norway — a country with a relatively homogeneous population, but a growing migration, today turned out to be, for that matter, together with the other European countries, in a difficult situation with Syrian refugees, comparable to the events of the mid-1990s, when Norway welcomed more than 11 thousand of Bosnians.

In addition, concerns that the emergence of thousands of Syrians might cause a negative reaction in a tolerant Norwegian society have some background. That concerns are primarily related to the terrorist attack on the 22nd of July 2011 and subsequent statements of its originator A. Breivik that his actions aimed at drawing attention to Islamization of Europe and speaking out against multiculturalism [1]. Thus, in 2011 it became clear that multiculturalism was not successful and Norwegian society had some anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic sentiments. The next four years of debates and discussions led to the transformation of the system and shift towards the so-called “model of cultural diversity”. Its effectiveness will be verified by the present situation and Syrian refugees’ issue as well.

Ethnic policy models in the Northern: historical perspective

Ethnic politics in the North of Norway has a long tradition of learning. Modern theories and scientific approaches to the study of the state ethnic policy in the North is really large due to the process of decolonization and the Sami cultural revitalization that had began several decades ago, intensive migration and sad events of 2011 in Oslo. In recent decades, a huge number of scientific articles and books devoted to culture, political representation and rights of indigenous peoples, their education, health, gender equality and discrimination was published. In Northern Norway, the Arctic research is mostly done by the employees of the University of Tromsø, its Sami Center, and representatives of the Sami College in Kautokeino. The research that had become classic for studies of indigenous peoples was made by the Norwegian anthropologist F. Bart [2], a researcher from New Zealand L.T. Smith, who developed decolonization methodology of indigenous cultures research [3], a political philosopher from Canada W. Kymlicka known for his contribution to the liberal theory of multiculturalism [4], B. Anderson and his research on nationalism [5] and etc.

Migrant issues are permanently on the pages of scientific publications and in the press, as well as the ongoing scientific debate on the concepts of tolerance, equality and solidarity, paramount for the Norwegian society. In terms of ethnic politics interesting research is done by Migration Policy Institute and specialists from the University of Oslo for the Norwegian Directorate of Migration (UDI) aimed at assessing the effectiveness of ethnic politics in Norway, potential problems, ways of development and improvement the ethnic situation in Norway [6, 7, 8].

Historical and political context of ethnic politics in Norway should be considered in the framework of four major policy models developed by a Norwegian researcher Einar Niemi and discussed in his books and articles on the history of the ethnic groups in Northern Norway [9]: acculturation, segregation, assimilation and multiculturalism that is questioned today [10].

Acculturation, as one of the models of national policy means a contact between different ethnic groups, accompanied by the diffusion of cultural elements: each group involved in the interaction takes over the elements of the culture of the “others” and vice versa. Acculturation unites, enriches and changes the culture; it creates common elements, reflected in language, religion, customs and so forth. The manifestations of acculturation are evident from the socio-cultural and psychological standpoint; in addition, it also means a psychological adaptation to living in close contact with the other cultures. Acculturation is vividly apparent in the border areas. Its echoes could be found, for example, in “Russenorsk” — a language Russian and Norwegian traders used to communicate in the 17th—20th centuries.

The study of acculturation began by American cultural anthropologists of the 20th century — R. Redfield, R. Linton, Herskovits M. and etc. In political terms, acculturation is primarily related to the preservation of culture, while enabling a particular culture to another. This is what had happened to Norwegian Sami when Norwegians appear on their land in 14th century. Archive sources indicate that in 12th—13th centuries the interests of the Scandinavian countries in the Sami lands were limited to taxes [11]. At the same time the first attempts at Christianization of the Sami people took place [12]. Contacts made the absorption of cultural elements a reality. For example, under the influence of neighboring cultures Sami had become Christians. However, the situation of the Sami had several difficulties in view of the fact that they resided in four countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia) and did not recognize state borders. So, Sami were often involved in international conflicts. In 1751 a special Sami Code for Norwegian and Swedish Sami was developed and approved. The document was issued in addition to the border treaty signed by the Danish and Swedish kingdoms. The Code did not only introduce rules restricting reindeer herding on the territory of other states, but it secured number of traditional rights the indigenous population of the border areas could enjoy.

Norwegian written records contain references to the 15th century and mention the Finnish population — Kvens. According to various estimates the number of Kven people in Norway today is 25 thousand [13, 254]. A separate ethnic politics towards Kven people did not exist for a long time. They were a subject to the common law, as well as other ethnic groups in Norway that time.

Acculturation as a political model in Norway existed until the end of the 18th century and affected the culture itself. Cultural processes were supplemented by power relations based on economic feasibility with no particular ethnic motivation.

Assimilation, the next model of ethnic policy towards Sami means that one culture is completely displacing the other and it is often violently. In the 19th century Norway was creating a nation-state after Constitution 1814. Unification trends were gaining momentum in the political life of the country and assimilation policies intensified. The main conductor of assimilation was the education system. Its goal was to replace the other languages and cultures and to provide complete “Norwegianization”. The changes primarily affected the Sami population. School education had become mandatory for all. Sami children were forced to leave their families and stay in boarding schools. Often all this happened by force and became a tragedy for the Sami families. In addition, in 1880s state laws restricted and then completely prohibited the use of the Sami language.

Assimilative model was lined up on the basis of the most rapid, large-scale and therefore effective methods based on coercion and maximum use of state resources. Assimilation was not something unique and designed only for Norway. A similar process could be observed in history of almost all states at the time of building up their national identities rooted in the culture of the majority. In the Northern Norway the use of the assimilation meant a loss of a considerable part of Sami culture by the middle of the 20th century and traditional way of life was associated with backwardness and regarded as something outdated, old-fashioned and not needed for the Sami people who preferred to associate themselves with the Norwegian culture. Traditions, language, lifestyle and identity were denied by the media and associated with “uncivilized” savagery and barbarism. From the point of view of the Norwegian state, assimilation had been as a positive phenomenon that time. It was “bringing civilization” to the “backward” Sami community. Assimilation contributed to the growth of national consciousness based on Norwegian culture, which after years of living within the Danish and Swedish states had to be “reinvented” as well and pass the collecting of its own cultural crumbs over the decades of the 19th century.

Segregation is often aligned with the assimilation model, which was used by the Norwegian State to treat Kvens after the government had established a legal framework for the separation of this ethnic group from the others. The scope of restrictions was visible in employment, as well as in the choice of place of residence and the purchase of land. Assimilation of Kvens was caused by the same reasons as the assimilation of Sami. Segregation elements had largely been justified by the fact that Kvens were living in the border areas. Norwegian authorities had seen them as a threat to national security, especially in the first half of the 20th century. Segregation policy model in Norway was partly used against the Jews, especially hard — during the Nazi occupation of the country. Rigid was the policy of the Norwegian State towards the Roma people, who in 1890 were not allowed to stay on the territory of the country, to get a passport and had to reside legally.

The political model of assimilation existed for over a century and had led, on the one hand, to the growth of national consciousness, based on the symbols of Norwegian culture, and, on the other hand, to the disappearance of cultural elements of the other ethnic groups in Norway, especially the Sami people. Assimilation as a model of ethnic politics was a response to the challenges of nation-building and represented one of the key elements of newly established national culture and identity. Also, military and emergency circumstances explain the segregation of the Jewish population in the 1940s. In relation to certain ethnic groups the government applied a mixed model of assimilation and segregation.

The middle of the 20th century, the end of the Second World War, the Nuremberg trials, the condemnation of racism, anti-Semitism and other forms of discrimination, discussions about human rights and European liberalism caused the revision of the assimilation policy in Norway. In the middle of the 20th century Sami regain their language, almost lost traditions and culture, which often had to be “reinvented”. Sami became a special object of domestic policy in Norway and gradually strengthened their position. In many ways, the cooperation between the Sami communities in the Nordic countries contributed to this process. The first international Sami organizations appeared, and in 1975 the World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP) established. And still Norwegian Sami are its active participants and they are supported by the Norwegian state. Linking indigenous issues with the general discussion on human rights, saying that loudly at the international level, the Norwegian Sami manage to be supported by Norwegian state. The situation had been changing even more in 1979, after protests against the construction of hydroelectric power stations on the Alta River. Sami got their Parliament, several committees in the national Parliament concerned with Sami culture and finally Sami got the same rights as Norwegians.

Around the same time the era multiculturalism begins. Multiculturalism represents a political model, based on the recognition of equality of cultures and aims at creation of favorable conditions for their existence and equitable development. The model of multiculturalism appears as the result of rethinking a wide range of issues of human rights, equality, and its existence became possible due to the triumph of European liberalism. Practical implementation of multiculturalism in Norway was the decision for, on the one hand, problems with the country's indigenous population, who demanded redress for years of assimilation, on the other — the rapidly growing rates of migration to the country since the 1980s. By this time, the state had been able to finance the establishment and operation of the relevant social institutions and non-governmental organizations contributed to the development of migrant cultures and their representation in the political life of the country.

Potential conflicts and ethnic policy transformation

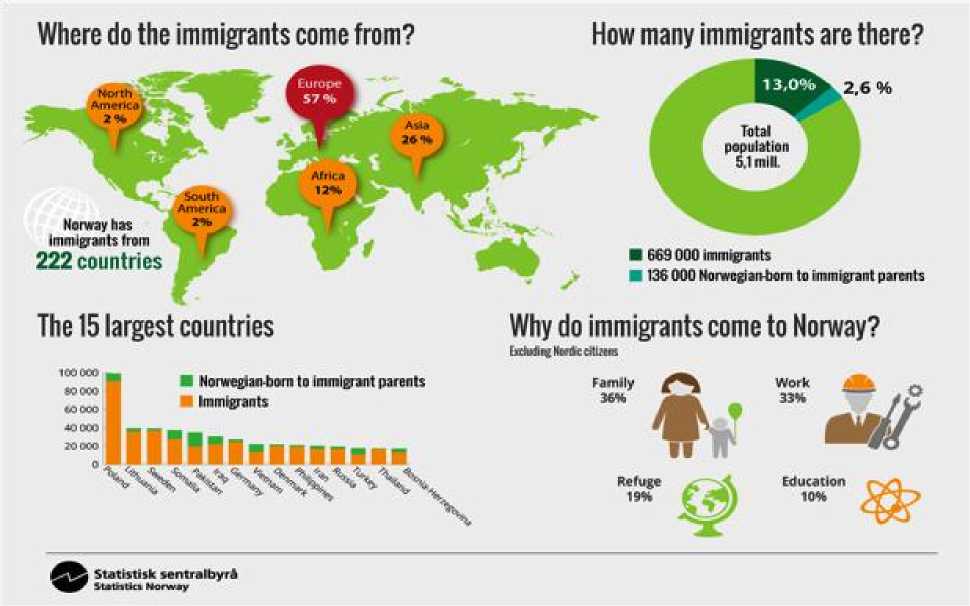

Norwegian welfare state looked attractive to the large number of migrants from all over the world, as evidenced by statistics (Picture 1). The very existence of a wide variety of ethnic and religious groups objectively implies a potential conflict. Despite the fact that tolerance, equality and solidarity still are the fundamentals of Norwegian society, not everything is so rosy. Treatment of migrants is largely influenced by stereotypes, political images of the state migrants are associated with and sometimes by the historical and cultural aspects of interaction between ethnic groups, such as in the case of migrants from the Middle East and Israel. Problems could reveal themselves not only in relations between migrant groups and Norwegians, indigenous people and Norwegians or immigrants, but also between particular migrant groups.

Picture 1. Migrants in Norway (01.01.2015) / Statistic Norway.

URL:

Over the last decade the total number of immigrants in Norway has increased by 3 times and is now more than 800 000 people (Picture 1). If we consider that the country's population is slightly more than 5 million people, the proportion of migrants is equal to 15.6% ad it looks rather high compare to the total number of people living in Norway.

Norwegian Statistical Office predicts a further increase in the number of migrants, especially in the capital of Norway — Oslo. The largest group of immigrants in Norway: Swedes, Latvians and Poles, however, the term “migrant” is rarely associated with them, typically the term refers to “non-Europeans”, usually — Muslims [14, 4].

Deciding economic problems and fulfilling all sectors of the economy with skilled labor and universities with diligent students from around the world, the state creates additional difficulties. A country with nearly homogeneous population gets a huge number of migrants from a completely different cultural background, often without the knowledge of not only Norwegian, but also English, with no education (Table 1), without the knowledge of local traditions and culture, but willing to get all the benefits of the welfare state at the expense of honest taxpayers.

Table 1

Migrants (over 16 years) and their educational level (01.01.2015)

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

|

Educated |

475 036 |

520 162 |

565 326 |

605 254 |

644 923 |

|

Without education |

8 164 |

8 601 |

9 293 |

9 353 |

12 216 |

|

Primary school |

123 242 |

131 769 |

140 759 |

148 869 |

189 571 |

|

Secondary school |

118 880 |

130 005 |

140 198 |

142 284 |

203 277 |

|

University or college short courses |

84 762 |

94 822 |

104 742 |

106 796 |

143 196 |

|

University or college educa tion |

45 667 |

52 892 |

60 607 |

63 207 |

95 427 |

|

Unknown |

94 321 |

102 073 |

109 727 |

134 745 |

1 236 |

Source: Statistic Norway. URL:

Modern Norwegian policy represents maneuvering between equality and diversity, unity and diversity, an attempt to integrate the “old” citizens and “new” ones with a foreign background. Multiculturalism implies the existence of ethnic communities and the policy built up with respect to their cultural and religious characteristics. Among all ethnic groups in Norway despite Norwegians themselves, the largest representation is provided for the indigenous people: the equality of languages, the policy of self-determination, collective and individual land rights, the Sami Parliament, support and development of the traditional lifestyle, training and studies in Sami language, Sami organizations. Norwegian Sami peoples have become leaders of the global movement for the rights of indigenous peoples and their organizations are actively participating in regional cooperation in the North and in the Arctic.

Multiculturalism is somewhat different for migrant groups of Norwegian society. It involves the preservation of their culture with the knowledge and acceptance of the fundamental norms of Norwegian society, namely tolerance, equality and solidarity. Thus, Norway seeks to adapt, and then integrate these groups of migrants. It is primarily done through the education and social support systems. State finances courses in Norwegian language and training programs. They are compulsory and are required in case of obtaining a long-term residence permit or work in Norway. Adaptation is carried out through various organizations that help migrants to settle down in the country, to find a job and new friends.

The model of a multicultural society implies that migrants could maintain their culture. The state encourages various cultural organizations and associations, which play a significant role in the life of communities. A striking example is the activity of Thai association in Tromsø. For many years it has been organizing a number of regular festivals there and it participates in all city events and festivals.

In Norway, one can easily get an education in a native language. Several dozens of such schools are opened in Oslo - Norway's most multicultural city. Special programs of adaptation and social integration are introduces in the communities with a significant number of migrants and refugees. These programs are established within the laws on migrants, as well as the state plan against discrimination and racism. The number of participants in such programs is increasing, and hence increases the number of potential “new” Norwegians (table 2).

Table 2

Participants of the introduction programs (01.01.2015)

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

|

Men |

5 956 |

6 541 |

6 612 |

6 756 |

7 456 |

|

Women |

5 889 |

6 253 |

6 532 |

6 925 |

7 223 |

Source: Statistic Norway. Introduction programs for immigrants URL:

In practice the problems exist, despite a serious state support. The North of Norway is still not able to resolve disagreements in a relationship with indigenous population, which is not satisfied with the current situation and insists on expanding the indigenous rights and demands control over the use of resources on their territories. A certain tension exists in case of Roma people in Norway. In the 1930s, the Roma people were subjected to forced assimilation, as well as other ethnic minorities. Assimilation policy continued until the 1980s, and the Department for the development of the Roma was closed only in 1990. The policy towards Roma and their culture has changed for the better, but a significant number of Roma children do not attend school as before. The problem of integration of the Roma still remains open.

In Norway, there is another ethnic group that has an ambiguous attitude — the Jews. AntiSemitism in Norway is not an issue, except for the period of Nazi occupation [14]. However, the Jews do not enjoy the “approval” in Norway (Norwegian — Godkjennelse or anerkjennelsen). The reason for all the fact that the country has increased number of Muslims, and the Norwegian government repeatedly states its sympathy for Palestine [14].

In recent years, researchers are writing about the inequality of ethnic groups in Norway [6, 8]. Inequality manifests itself in the field of employment, where the total share of employment among immigrants or people with foreign background is lower than among Norwegians [8]. That’s why the Confederation of Norwegian companies (NHO) has repeatedly called its members to hire immigrants and Norwegians with a foreign background. Statistics shows that the percentage of unemployment among immigrants is 3 times higher than among non-immigrants (tab. 3).

Table 3

Registered unemployment rates among immigrants, 15-74 years (%)

|

2014 K1* |

2014 K2 |

2014 K3 |

2014 K4 |

2015 K1 |

2015 K2 |

|

|

Non-immigrants |

2,1 |

1,9 |

2,2 |

1,9 |

2,2 |

2,0 |

|

Immigrants |

7,4 |

7,0 |

7,2 |

6,7 |

7,6 |

7,1 |

*K1 – sign for the quarter of the year

Source: Statistic Norway. URL:

Inequality could be seen in the choice of areas for living, allegations of crime, gender equality and religion. For example, in Oslo, migrants prefer to live in the eastern part of the city, and Norwegians — in the western. The media and press often contains of debates on the connection between migration and crime [15]. Muslim women wearing the hijaab are often a part of the public debate on the equality [16]. Cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad in a Danish newspaper were reprinted by a Norwegian magazine [14, 10]. In addition, the Norwegian society got signs of Islamophobia. All those statements could be supported by statistical data of the parliamentary elections and the increasing number of votes for the Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) and its negative sentiments toward Muslims and Islam in Norway. In 2013 the Party won 29 seats in Parliament and joined the government for the first time [17].

Focusing on the negative aspects of the ethnic politics in Norway, we should not forget that multiculturalism solved the most urgent problems of ethnic relations so that they are not turned into an open confrontation, as had happened in other European countries. The tragic exception was the year 2011 that made Norwegian society and officials to draw more attention to the shortcomings of multiculturalism and correct the model of ethnic politics. Multiculturalism in Norway was a natural phenomenon and it fit perfectly to the fundamental values of Norwegian society, with its high level of tolerance and openness. After 2011, and victory of the Conservative repre- sentative Erna Solberg the situation has been changing. The fact that at the elections 2013 the center-right party formed an alliance with Norwegian Progress Party, did not foretell the further liberalization of the Norwegian ethnic politics. However, anti-migrant rhetoric of the Progress Par- ty has diminished a little.

Picture 2. Norway accepts immigrants that bicycle via its border with Russia 2.

Some changes have affected the interests of the migrants. Now, in Norway it is more difficult to get a refugee status, and the Norwegian state is stricter with social guarantees and privileges for migrants. Oil prices are falling and unemployment in certain sectors of Norwegian economy is growing. The country is interested in skilled workers in areas where they will not compete with its citizens. Back in 2013 E. Solberg said that highly skilled workers would receive a visa on an accelerated scheme [18]. In addition, Norway firmly made it clear for the European community

2 URL: ; imagecache/full/news/10/23/892450/; that the country would not accept more migrants than its quota. In relation to indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities Erna Solberg continues the policy of predecessors. Not long ago, the press reported that Prime Minister apologized for the assimilation policy against Roma people and agreed to pay compensation [19].

Conclusion

Norwegian ethnic policy in a historical perspective is a change of political models of acculturation, assimilation, elements of segregation of certain ethnic groups, and the model of multiculturalism which could be called a model of cultural diversity after T. Eriksen’s articles [6]. For a long time, Sami people and a small migrant population were a subject to the state ethnic policy. Initially, the policy of the state was formed on the basis of economic feasibility. Later, the establishment of the nation-state, national culture and identity changed the model and caused the strengthening of assimilation and use of the certain elements of segregation policy. The second half of the 20th was marked by a triumph of multiculturalism as a response to globalization, intensive migration and the emergence of a multi-ethnic and multi-religious Norwegian society. Recent debates and critics of multiculturalism, as well as the acts of terrorism, not only in Norway but also in other European countries and global economic crisis transformed the public mood and led to the revision of the ethnic policy model. Norway remains faithful to the basic principles of multiculturalism, but trends towards the transformation of its ethnic policy, greater control over migration, budget, programs for the integration of migrants and their efficiency is noticeable. All these does not mean the desire of the Norwegian state to hold a soft assimilation, but rather appears as an attempt of incorporating different cultures into its own.

Maneuvering between the public interests, ethnic policy model is getting clearer. Gradually blurred background of liberal multiculturalism is getting a concrete shape of cultural diversity, united in a single state and civic identity. From a distance, this model resembles the attempts of the Soviet government in Russia to form a unity in diversity of cultures and nationalities, to build up a “supranational’ civic identity and thereby to avoid differences on the ethnic, national and religious grounds.

Regarding the applicability of the model of ethnic politics in Norway to harmonize ethnic relations in the North of Russia and in the Russian Arctic, it could be argued that it is necessary to look at the experience of Norway in respect of indigenous cultures, and social support of the population of the Far North. The advantage of the Norwegian system is that it is attractive to indigenous peoples and migrants. Indigenous peoples shall have the support and recognition of their cultures, as well as the opportunity to participate in decision-making that directly affects their lifestyle, culture and traditions. For Russia, the issue of supporting indigenous cultures often rests on the finances. Questions of political representation and rights of indigenous peoples are rather often viewed as matters of separatism. Economic feasibility of the development of natural resources of the North make the issue more complicated and therefore it requires a special adaptation to the Russian circumstances.

Within the Norwegian ethnic policy model, migrants feel welcomed and have no negative feelings about their ethnic or confessional background which gets one more up-level of Norwegian civil identity incorporated with the fundamentals of Norwegian culture. Combining all these processed with the power of social integration, Norway gets a society with low levels of ethnic and confessional conflicts. This mechanism could be used in the case of migration to the North of Russia. However, this aspect is not relevant due to the negative demographic trends in the Northern and Arctic areas of Russia.

Список литературы Maneuvering between icebergs: ethnic policy models in Norway

- Krasulin A. Anders Brejvik: Vo vsem vinovato NATO. Vesti. 24 iyulya 2011. URL: http://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=517568 (Accessed: 01.10.2015)

- Barth F. Ethnic groups and boundaries. Social organization of cultural difference. Illinois: Waveland Press Inc., 1998. 153 p.

- Smith L. T. Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous people. London-NY: Zed Books Ltd, 1999, 220 p.

- Kymlicka W. Multicultural citizenship. A liberal theory of minority rights. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995. 280 p.

- Andersen B. Imagined communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London-NY: Verso, 2006. 240 p.

- Eriksen T.H. Immigration and national identity in Norway. Oslo: UiO, 2013. 22 p.

- Eriksen T.H. Xenophobic exclusion and the new right in Norway Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2012 Vol. 22 No 3, pp. 206—209

- Sølt S., Wessel T. Contextualizing ethnic residential segregation in Norway: welfare, hous-ing and integration policies. Oslo, 2010. 69 p.

- Niemi E. Ethnic Groups, naming and Minority Policy. In Elenius L., Karlsson Chr. (Eds.): Crosscultural communication and ethnic identities: proceedings II from the conference Re-gional Northern Identity: From Past to Future at Petrozavodsk State University, Petroza-vodsk 2006. Luleå: Luleå University of Technology, 2007, pp. 21—35

- Anderson M. The debate about multicultural Norway before and after 22 July 2011. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 2012. Vol 19. No 4, pp. 418—427

- Goldin V. I., Zajkov K. S., Tamickij A. M. Saamy v istorii rossijsko-norvezhskoj granicy: faktor napryazhyonnosti ili regionalnoj integracii? Bylye gody. Rossijskij istoricheskij zhurnal, 2015. Vol. 37. No. 3. URL: http://bg.sutr.ru/journals_n/1442664611.pdf (Accessed: 01.10.2015)

- Myklebost K., Niemi E. Minoritets-og urfolkspolitikk i nord. Russland kommer nærmere. Norge og Russland 1814-1917/ J.P. Nielsen(red.). Oslo: Pax forlag A/S, 2014, 643 p.; Naboer I frykt og forventning. Norge og Russland 1917—2014/S.G. Holtsmark (red.). Oslo: Pax forlag A/S, 2015, pp. 318—342

- Livanova A.N. Finny v Norvegii. Skandinavskie chteniya 2006—2007. Otv. red. I. B. Gubanov, T. A. Shrader. SPb.: MAE' RAN, 2008. Pp. 254—263

- Moore H. F. Immigration in Denmark and Norway: Protecting Culture or Protecting Rights? Scandinavian Studies, 2010. Vol. 82, No. 3. pp. 355—364

- Norway: Crime Drops as Police Deport Record Number of Nonwhite Invaders. The New Observer. 13 November 2014. URL: http://newobserveronline.com/norway-crime-drops-po-lice-deport-record-number-nonwhite-invaders/ (Accessed: 01.10.2015)

- Bangstad S. Public Voice of a Muslim woman. URL: http://blogs.ssrc.org/tif/2015/08/05/ thepublic-voice-of-muslim-women/ (Accessed: 01.10.2015)

- Widfeldt A. Extreme right in Scandinavia, London-NY: Routledge, 2015. pp. 82—127

- Norway wants more migrant workers. The Nordic Page. 27.12.2013. URL: http://www tnp.no/norway/panorama/4207-norway-want-more-migrant-workers (Accessed: 01. 01.2015)

- Solsvik T. Norway's prime minister apologizes for treatment of Romas during World War Two. REUTERS CANADA. 08. April 2015. URL: http://ca.reuters.com/article/topNews/id-CAKBN0MZ22N20150408 (Accessed: 01.10.2015)