Memory and identity: Tashi Tsering, the last qinwang south of the Yellow river

Автор: Wallenbck U.

Журнал: Вестник Новосибирского государственного университета. Серия: История, филология @historyphilology

Рубрика: Этнография Восточной Азии

Статья в выпуске: 10 т.21, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Today’s Henan Mongol Autonomous County is located in the southeastern part of present-day Qinghai Province, in the northeastern part of the Tibetan plateau. This historical pastoral area South of the Yellow River is a border area where, a milieu was created due to the long-term mutual contacts between Tibetans and Mongols, in which specific local customs, language patterns, and social communities have emerged. The initial turning point in their ethnical and cultural identity was the integration into the modern Chinese State in 1954, followed by ethnic classification. Moreover the local pastoral Mongol and Tietan populations have been transformed into minority nationalities is-á-vis the Han Chinese, and many Tibetans even were classified as Mengguzu (Mongols), however, perceived as Tibet-Mongols (Tib. Bod Sog) by themselves and their neighbours. By looking at the outstanding historical figure of Tashi Tsering, the last Mongol qinwang of the Henan grasslands at the Sino-Tibetan borderlands, this paper examines how the people of the Henan grasslands integrate their memory of the local traditional leader into their identity construction, and how they revive their Mongolness despite their seclusion from other Mongol communities.

Tashi tsering, qinwang, mongolness, identity, museum, memory

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147239010

IDR: 147239010 | УДК: 394 | DOI: 10.25205/1818-7919-2022-21-10-51-62

Текст научной статьи Memory and identity: Tashi Tsering, the last qinwang south of the Yellow river

The construction of cultural memory is always a precondition for the emergence of a distinct sense of belonging and community, which is premised on the groups’ own local history: their specific local and personal experiences. Hence, this article considers one example of a local leader who was the driving force for the transformation from a Mongol “principality” (qinwang guo 亲王国) into a Mongol autonomous county, and who became the local ‘ethnic heroine’ as well as a symbol for Mongol nationality by representing her ethnicity: Tashi Tsering (Tib. bKra shis Tshe ring, Chin. Zhaxi Cairang, Chin. 扎西才让 or 扎喜才让) (1919/20–1966), the last qinwang 亲王 (Tib. chin wang, Manchu: cin wang) 1, Princess of the First Order, of the Hequ grasslands and the first county governor of Henan Mongol Autonomous County (MAC) (Henan Mengguzu Zizhixian 河南蒙古族 自治县, Tib. rMa lho sog rigs rang skyong rdzong), situated within contemporary Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (Huangnan Zangzu Zizhizhou 黄南藏族自治州, Tib. rMa lho bod rigs rang skyong khul) in the south-eastern part of Qinghai province within the People’s Republic of China (PRC) 2. Up to now, Tashi Tsering is praised and even officially remembered, as for instance stated by an elderly member of the Communist Party in 2014, “Comrade Tashi Tsering keeps always living in our hearts”. Moreover, in the book Fengfan changcun 风范长存 (“Merits Forever”), published for the 40th commemoration of her death, a former comrade of Tashi Tsering praises her officially:

On 21 October 2006, […] [o]n this day, exactly 40 years ago, our Party lost a sincerely cooperating, loyal-hearted, critical friend; the cause of the CPPCC has lost a comrade, who was diligent and dedicated to her work, and brave in her devotion [Han, 2006, p. 1, translation by the author].

As a symbol of Mongolness, images and artefacts associated with her are disseminated even by the local government, for instance by having opened the Mansion as a Museum heritage site in 2009, wherein the qinwang lineage is the main theme. Despite the fact that the building is officially referred to as the Palace of Happiness and Tranquillity (Tib. Pho brang bde skyid rab brtan , Chin. Funing gong 福宁宫 ), this article will use the English term ‘Mansion’ as it used to be the Mansion of the qinwang Tashi Tsering and the new name is not known by locals. The museum complies with government demands and contains a lot of artefacts associated with Tashi Tsering – not only personal items, but also her furniture. However, the main attraction is the Mansion itself, as a memorial to the qinwang lineage on one hand, and as a memorial to Tashi Tsering on the other hand. Hence, this paper presents issues which are interwoven with the history of the contemporary Henan MAC and the representation of local history of the Communist Party of China (CPC); the museum plays a major role in the construction of collective identity by providing narratives of the past which are associated with the national history and the legacy of the central government of the people of the Henan grasslands. Drawing on field research in Henan MAC in spring 2014 and summer 2017, it is clear that the Mansion provides a vehicle for bridging the Mongol-Tibetan, as well as the Sino-Mongol, relations in this area through exhibiting tradition, modernity, and ethnic identity: throughout the museum, emphasis is put on the restoration of socialist values, as well as on the increase-ment of patriotism and nationalism among the local population by presenting Tashi Tsering as local heroine and not to forget the ‘heroism’ of the Chinese Communist Party ‘liberating’ the ‘old society’ of the Mongol grasslands. In fact, the Mansion turned into a memorial and education base, as well as into a protected heritage site and museum. Moreover, the museum determines and narrates the politicized reconstructed national past.

Museum, History and Collective Memory

Museums are part of the culture of remembrance. In China, museums promote China’s ‘splendid’ culture and particularly the development process under the leadership, the principles and governing philosophy of the CPC, and also the good character of Chinese people and their efforts to maintain stability and unity. In terms of the PRC, museums ‘have been used as tools by the State to propound officially sanctioned views of modern history,’ as well as being ‘pedagogical tools for the teaching of Party history to the masses’ [Denton, 2005, p. 567]. In fact, museums are the key institutions responsible for shaping public memory for the purpose of consolidation of the CPC’s State ideology and creating national unity. Museums reinforce nationalist feelings among the population, emphasising the grand narrative inspired by socialist nationhood and the communist revolution [Denton, 2014, p. 26]. The Mansion is part of a State-sponsored memory initiative aiming to legitimize the past through the eyes of China’s historiography, with an emphasis on the Henan Mongols’ loyalty towards the Qing empire, Republican China as well as the Modern Chinese State.

However, the Mansion is not only a museum but also a memorial site, therefore, by looking at the last qinwang Tashi Tsering, the definition of ‘memorial museum’ given by the International Committee of Memorial Museums 3 is as follows:

The purpose of these Memorial Museums is to commemorate victims of State, socially determined and ideologically motivated crimes. The institutions are frequently located at the original historic sites, or at places chosen by survivors of such crimes for the purposes of commemoration. They seek to convey information about historical events in a way which retains a historical perspective while also making strong links to the present.

The Mansion is used as a mechanism for legitimating the Henan MAC Mongol ethnic group in the eyes of the Central government. This memorial museum serves as a centre for education, documentation, and history-telling which should expand knowledge about the context of the qinwang lineage, and its relations with the Chinese territory. In brief, this museum is devoted to the history of the qinwang lineage with carefully selected and constructed exhibitions of cultural artefacts, early revolutionary historical materials of the working committee, and personal objects including daily items from Tashi Tsering. Moreover, texts, pictures, and objects displayed reflect the history of the qinwang lineage, all embedded into China’s presentation of national history. Intriguingly, during the author’s stays in the Henan MAC, when mentioning the first qinwang , all interviewees repeatedly mentioned the importance of Tashi Tsering, but emphased that Tsagan Tenzin (Tib. Tshe dbang bstan ‘dzin, Chin. Cahan Danjin 察罕丹津 ) was the first qinwang, reigning from 1725 until 1735, and Tashi Tsering was the tenth and last one. Thus, bridges are built between the past, the present, and future. Memory about the past is restored to understand the present situation, which is needed to explain the attitude of the Henan Mongols towards the Chinese State. Hence, this museum is one of the institutional forms in which the local Mongol community shape its collective identity based upon the historical figure of Tashi Tsering as well as Tashi Tsering in her position as qinwang , in addition to the powerful position as a leading figure, who was the one enforcing the local Mongol community transition from a traditional to modern society. Both in the official record and in the memory of the local community, Tashi Tsering is credited with having sustained and revived Mongolian identity in Henan MAC. She even became an ethnic hero [Dhondup and Diember-ger, 2002, p. 217].

The qinwang Mansion

The local government opened the memorial Mansion of the traditional Mongol rulers in Nyinta township (Tib. Nyin mtha’, Chin. Ningmute 宁木特 ) in Henan MAC on 28 May 2009. The original Mansion was built as a summer palace for the qinwang by Tashi Tsering’s mother in 1941, finished in 1947, and demolished in course of the rebellion in 1958. Then, in 2007, the government reconstructed the Mansion which now serves as a museum.

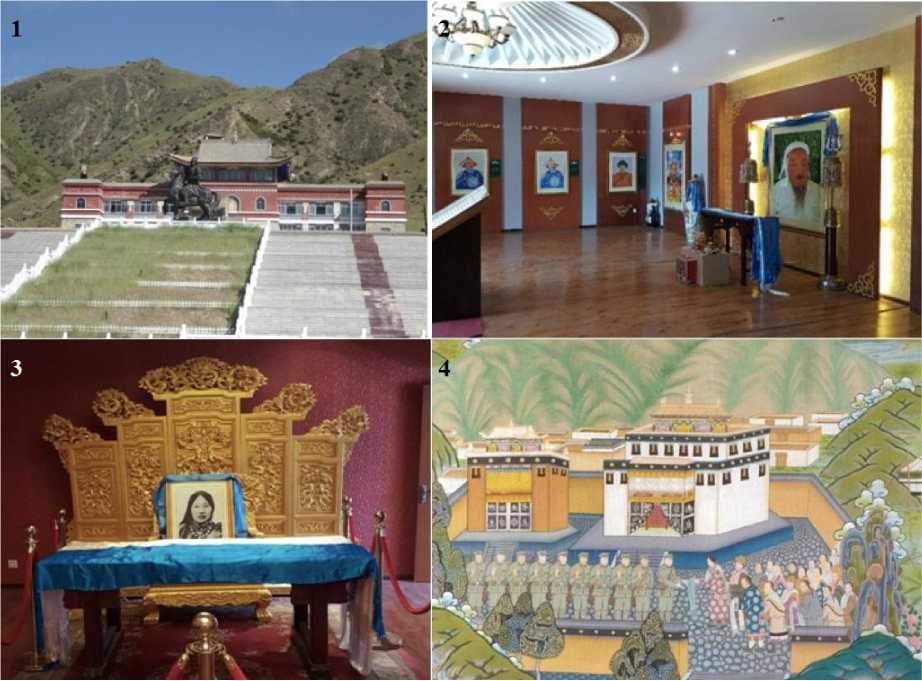

The main building of the Mansion was built on the ruins of the original Mansion, and over three-storeys combines Han-Chinese, Mongolian, and Tibetan architectural styles. The twenty-five stairs up to the main building is said to symbolize the lifetime of the ninth qinwang , who passed away at the age of twenty-five. The length of the Mansion is forty-six meters, referring to the forty-six years of lifetime of Tashi Tsering; the reversed number of sixty-four symbolizes the life of her mother, Lumotso. The height of the mansion is twelve metres, referring to Tashi Tsering’s twelve-year reign as the last qinwang (see figure, 1 ). Altogether, this memorial Mansion comprises three parts: The Exhibition Hall of Culture and Art of Henan County ( Henan Mengguzu Zizhixian wenshi chenlie guan 河南蒙古族自治县文史陈列馆 ), the Early Office of the CPC Henan Mongol Banners Working Committee ( Zhonggong Henan Mengqi gongwei zaoqi bangongchu 中共河南蒙旗工委早期办 公处 ), and the Mansion of the former qinwang ( Quge qinwang fu 曲格亲王府 ). In the former, the single room, exhibits objects of the qinwang and other local leaders – such as saddles, weapons, and a leather wallet.

In the Early Office of the CPC Henan Mongol Banners Working Committee there is an exhibition of the periods before, during, and after “liberation”, starting with an introduction in Chinese language on the ruling system before “liberation”, followed by a brief explanation of the Mongol

Banners and the “liberation”, the period of conflicts with the Ma-warlords 4, and finally a description of the establishment of Henan MAC. The various texts are highlighted with black-and-white photos featuring trilingual (Chinese, Tibetan, and English) subtitles, on a red wall. All photos highlight “peaceful” liberation and the friendship between the members of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the locals.

In the Qinwang Tashi Tsering Museum:

1 – the mansion (museum building); 2 – hall of ancestors; 3 – throne; 4 – depiction of the event on 20 September 1949, when qinwang Tashi Tsering goes to Labrang to welcome the PLA to come to the Henan grasslands. All photos made by the author

В музее цинвана Таши Цэринг:

1 – дворец (здание музея); 2 – зал предков; 3 – трон; 4 – изображение событий 20 сентября 1949 г., когда цинван Таши Цэринг отправилась в Лабранг приветствовать бойцов НОАК, вступивших в степи Хэнани. Все фото автора

Entering the Main Hall of the Mansion, there is a portrait of Genghis Khan in its centre, and to its sides, there are portraits (see figure, 2) of all ten qinwang and brief biographies. In the other rooms of the first floor of the Mansion there are exhibitions of objects and texts, mainly regarding the Labrang Monastery. The second floor features the living quarters of the last qinwang. In the living room, the displayed objects reflect Tashi Tsering’s personal interests in music. On the same floor, there is a room with her throne (see figure, 3), and on the surrounding walls are photos and portraits of various local leaders. There is also a room for a Buddhist altar and an adjoining guest room for Jamyang Zhepa (Tib. ’Jam dbyangs bzhad pa, Chin. Jiamuyang Xieba 嘉木样协巴), a lineage of incarnations with its primary seat at Labrang monastery, and his throne, above which hang portraits and photos of all the incarnations. Having an extra room for Jamyang Zhepa indicates the relationship between the Henan qinwang and the Labrang monastery 5.

“Qinwang” Tashi Tsering (1919/20–1966) 6

Tashi Tsering was born around December 1920. She is the daughter of Lumantso (Tib. kLu sman mtsho, Chin. Lanmancuo 兰曼措 or Luge 鲁阁 ) 7 and Paljor Rabten (Tib. dPal ’byor rab brtan, Chin. Balezhu’er Labudan 巴勒珠尔啦布坦 ) 8. After the sudden death of her brother Kunga Paljor (Tib. Kun dga’ dPal ’byor, Chin. Gengga Huanjue 更嘎环觉 ) on the thirteenth day of the sixth month in 1940 (which is, according to the Gregorian calendar, 17 July 1940 9), the unmarried Tashi Tsering ascended the throne as the tenth qinwang in 1940 10. Because Tibetan and Mongolian society was predominantly patriarchal and patrilineal, it was a shock when the last male successor of the qinwang throne suddenly passed away and a female was assumed heir to the throne. Thus, Lu-mantso not only took care of succession but also had a great influence on her daughter, as described by Xiao Ying 萧瑛 in a newspaper article:

Her name is Tashi Tsering, […] She is categorized as Mongolian ( Mengguzu 蒙古族 ), but in terms of social habit and custom (she is) tibetanized. She does not know the Mongolian script, cannot speak Mongolian, but knows Tibetan well and now she is learning Chinese. If you do not know that she was a descendant of the royal lineage, you would not think that Genghis Khan is her ancestor. […]. She is gentle and has soft and peaceful generous manners, […], without any air of arrogance, […]. She keeps sitting next to her mother, looking like an obedient child, staying quiet when mother has a conversation with somebody else. […] making cautious inquiries and seems to show her approval or understanding her mother’s opinion ( Funü yuekan 妇女月刊 The Women’s Monthly Magazine, Vol 4, Issue 4; cited from: [Han, 2006, p. 134], translation by the author).

This report indicated that the success of Tashi Tsering is based on her ability to utilize her gender role as a key tool to achieve over-all respect 11. Much emphasis is put also on Tashi Tsering’s educational background, which is important for the Chinese who regard neighbouring peoples as less educated, which cannot be applied to Tashi Tsering.

In 1943, Tashi Tsering married to Gompo Namgyal (mGon po rnam rgyal; Amgon) or also known by his Chinese name Huang Wenyuan 黄文源 , son of Apa Alo, known also as Huang

Zhengqing 黄正清 12, a prominent figure from Labrang 13. This (political) marriage 14 between Mongols and Tibetans was an important stroke against the Muslim power of the Ma family; during the Republican era, contemporary Qinghai province was ‘a patchwork of more or less autonomous clan- and monastery-based polities and estates, […]’ who had not, notes Rohlf by quoting a Chinese writer, ‘yet escaped from the systems of kings and princes’ [Rohlf , 2016, p. 7]. At this point, one should be aware and reflect the complicated history of marriage alliances and competing networks during that period of time, sometimes even cutting across ethnic boundaries.

Then, while attending the National Congress in Nanjing, Tashi Tsering and her husband became members of the Guomindang (GMD) as local representatives on 12 March 1947. At that time, Tashi Tsering was celebrated as the “Queen Elizabeth of China’s frontier” ( Zhongguo bianjiang Yilisha-bai 中国边疆的伊丽莎白 ) in the Chinese media from the Guomindang: the Zhongyang Ribao 中央 日报 (Central Daily News), Xibei Ribao 西北日报 (Northwest Daily), and the Funü Yuekan 妇女 月刊 (The Women’s Monthly Magazine). Later, she was also called “Elizabeth of the East” ( Dongfang de Yilishabai 东方的伊丽莎白 ) and / or “Elizabeth of Qinghai” ( Qinghai de Yilishabai 青海 的伊丽莎白 ) [Han, 2006, p. 145]. It is supposed that these refer to British Queen Elizabeth I, because she has been a regent of a golden time and a woman. Elizabeth I must be, at least in the context with Tashi Tsering, exclusively seen as an icon of “Britishness”, hence, in Republican China she was associated with “the prestigious British royalty” and used as “a marker of ethnic Mongolian support for the Guomindang” [Dhondup, Diemberger, 2002, p. 211].

Returning to her behaviour in terms of political power, in August 1949 Tashi Tsering accompanied her husband and his father to pay tribute to the arriving People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in Lanzhou, and to show support for the Communist Party of China (CPC) as representative of Labrang and the Henan grasslands. This was a welcomed step for the CPC; they had been seeking support from local political leaders. As the leader of the Henan Mongols, Tashi Tsering (together with most of the local leaders) supported the leadership of the CPC during the upcoming “liberation” of the Henan grasslands by becoming a party member. She believed in the CPC’s aim to integrate border regions into the newly established Chinese State with Beijing and the CPC as centres of power, and in the economic development of the Henan grasslands.

Following official local histories, the Working Committee of Henan Mongol Banner ( Zhongguo gongchandang Henan Mengqi gongzuo weiyuanhui 中国共产党河南蒙旗工作委员会 ) was founded in Xining in June 1952, and subsequently the PLA officially arrived in the Henan grasslands on 11 August 1952, where they were warmly welcomed with local Tibetan and Mongolian songs and dances (see figure, 4 ). Whereas according to an informant, who was 73 years old at the time of the interview, recalled bloodshed by military forces. In fact, besides the warm welcome, ‘there was in fact some resistance – perhaps quite significant resistance – from among the local population’ [Dhondup and Diemberger, 2002, p. 212].

With the arrival of the PLA, Tashi Tsering took over several official positions within the CPC-apparatus, which was in the local context quite unusual for a woman and especially as a member of the formerly aristocratic family at that time. In February 1954, Tashi Tsering was appointed as head of the organizing committee as well as a standing member of the Chinese People’s Political Consul- tative Conference (CPPCC) committee in Qinghai province. She was positioned as a symbol of her nationality within the Chinese State. On 16 October 1954, a second meeting was organized, focusing on several topics such as the political structure, and the ‘nationality’(minzu)-question. Tashi Tsering was “elected” (xuan 选) (but most likely with the meaning of “appointed”) head of the new administrative organized area. This meeting was then followed by the proclamation of the Henan Mongolian autonomous Region (Henan Mengzu Zizhiqu 河南蒙族自治区) on 20 October 1954. Most of the Henan grassland’s population had been classified as Mongol (Mengguzu 蒙古族) – but perceived themselves as Tibet-Mongols (Tib. Bod Sog) [Wallenböck, 2019b] – to obtain an autonomous status by being surrounded by Tibetans, and to place themselves as an independent party at the Sino-Tibetan borderland. Moreover, by then the former elite were officially transformed into servants of the people, since the newly established Chinese State intended to construct a homogenous state by replacing the “old society”. Politically, Tashi Tsering was used as a figurehead with all the trappings of power, but without normal agency, where actual decision-making is in the hands of the Han secretary and not the local non-Han leader [Wallenböck, 2019b].

In the following years, Tashi Tsering further accepted the responsibilities of duty as ViceSecretary General and Deputy Director of Qinghai‘s women’s federation, which makes her a quasifeminist heroine. Her work was mainly focused on the issues of amity between nationalities ( minzu tuanjie 民族团结 ), religious affairs, and on stability in political affairs.

Tashi Tsering acknowledged the central power of the CPC and its ideology by supporting the aim of equality among all minzu , and between men and women. Besides being a quasi-feminist, Tashi Tsering provided a good example of the ideal, traditional family life for people from the Henan grasslands. Despite her political obligations, Tashi Tsering went on a pilgrimage to Lhasa to gain merit for the soul of her deceased mother Lumantso in 1956. She returned to Henan MAC in 1958, where some revolts had already occurred as a response to the implementation of new reforms from the Chinese government, or to the anti-right wing campaign, which aimed to develop the “backwards” region within the modern Chinese State. According to the Henan xian zhi [1996, p. 731], on 3 May 1958, an armed counter-revolutionary revolt occurred in some places of Henan Region, described by some informants as “violence and bloodsheds.” Then, during new administrative reforms in June 1959, the name of the Henan grasslands was transformed into the Henan MAC with Tashi Tsering as the first head of the county. In 1960, she was sent to Beijing to the Central Nationality College to study together with other regional leaders for about one year to obtain a better “education”, an implicit expression for becoming “cultivated.”

After her return to Qinghai, she gained more prestige within the CPC, especially after her marriage to her former cook Sherab (Tib. Shes rab, Chin. Xierebu 谢热布 ) in 1962. Having taken her former servant as her second husband would have been impossible before the take-over of the CPC, but due to the abolition of feudalism, this was a welcomed alliance between the former local hierarchies and was moreover used as a showpiece of communist ideology.

Then, with the Cultural Revolution, because of her birth and her “historical problems” ( lishi wenti 历史问题 ) Tashi Tsering became the main target and victim of this movement as she was representing the “Four Olds”. One of her comrades recalls that in August 1966, Tashi Tsering was “overthrown” ( dadao 打倒 ), one month later she was accused of being a “rebel faction” ( zaofanpai 造反派 ) and was forced to enter the “cowshed” ( niupeng 牛棚 ). Then, on 20 October 1966, Tashi Tsering was picked up in a truck by a provincial delegation to be taken back to her family in Henan MAC.

As reported in various written sources, after having arrived in Henan MAC in the early morning of 21 October 1966, she was arrested in a yurt. Then, in the afternoon. another session of criticism, denunciation, and beating took place which lasted until the late evening, which resulted in her death around 11 p.m. Her thirteen-year-old daughter Paljor Wangmo (Tib. dPal ’byor dbang mo, Chin. Huanjue Angmao 环爵昂毛) was the only witness of her terminal breath due to assumingly heart problems. The official version of her death was “suicide by poison” (fudu zisha 服毒自杀) 15 [Han, 2006, p. 72]. According to the Huang He Nan Menggu zhi [2010, p. 459], she “could not bear the attacks from all sides and to be criticized and denounced publicly for her errors, unfortunately she passed away because of false accusations”. The circumstances of her death are still uncertain.

After her death, Tashi Tsering’s body was supposed to be cremated, a funeral which is traditionally reserved only for royals, eminent monks, and “heroes” 16. But, because of the time of her death, there has been a controversy regarding her funeral; according to people loyal to communist ideology, she was supposed to get an earth burial, which has been interpreted by people loyal to her as humiliation. After the rehabilitation on 30 August 1980 in a great ceremony in Xining Hotel, her corpse was exhumed and then cremated. Since 1997, her relicts are kept in a stupa in the Assembly Hall of Labrang monastery. To the present day, many loyal people from the Mongol Banners continue to pay respect to the “Mongol heroine” and honour her by burning incense in front of her royal mansion in Labrang, a place where memory and history interact with symbolical significance. By performing the bodily action of going to pay respect to the former mansion of the qinwang , this terrestrial place becomes a place of memory, which belongs to the present as well as to a certain period of time reaching back into the past. However, the affiliation to the qinwang lineage made and still makes Tashi Tsering an important female political leading figure, a powerful player in exercising alliances in religious, military and political context by putting an emphasis on her “Mongolness”.

“Mongolness”

Considering Khan’s argument that “there is no such […] category as the Mongol community or nation, but rather various local groups, whom the Chinese conveniently referred to as Mongols” [Khan, 1995, p. 251], the perception of Tashi Tsering as being the icon of “Mongolness” should be questioned. For me, “Mongolness” involves consciousness constructed on shared values embodied in ethnicity, history, and beliefs. In the context of the Chinese State, icons such as the various Henan qinwang are used to represent “Mongolness” in superficial terms by pointing out collective solidarity, which again is articulated by the State to construct Mongol identity to mark one’s loyalty in contrast with the neighbouring Tibetans. The local population identifies themselves with the territory of the historical Mengqi 蒙旗 (Mongolian Banners); the collective memory is shaped by relating to identity and space, whereas space is a place of remembering, a place in which elements of the past are cobbled together. Thus, it can be stated that the “Mongolness” of the Henan Mongols is not an artificial construct by the modern Chinese State as might be the common perception but refers to its history pillars [Wallenböck, 2019b].

First, the reference to Mongol identity is belief in the Henan grasslands belonging to the ancient Mongol empire of Genghis Khan; secondly, (fictive) descendants’ lineage from the qinwang tracing back to Genghis Khan; and third, the close relation to the Buddhist monastery of Labrang, which the qinwang used to be the patron of. Concerning power relations, the people of the Henan grasslands were not referred to as “peripheral” in history, as the Mongols per se used to be the actors of power-seeking in that area with Labrang as its centre. In fact, the relation between Labrang monastery and the Mongol qinwang displays the existence of potentially strong rallying points for collective solidarity and loyalty among Tibetans and the Henan Mongols. Only after incorporation into the modern Chinese State in 1954 did the Chinese government try to make the Henan Mongols distinguish themselves from the surrounding Tibetans by referring to their cultural memory. This retreat into the “roots” has been supported by the Chinese State since the 1980s by developing ethnic consciousness as well as cultural identity among “national minorities” and by reproducing stereo- typic representations of “Mongolness”. This State-sponsored strategy is based on the association with the historical Mongol presence in the region.

Conclusion

Contemporary Henan MAC invokes memories of the Mongol past in the Qinghai Tibetan areas, even though the Mongol population is ethnically described as being neither mainstream Mongol nor mainstream Tibetan; they are people of mixed descent. In a political context, the Henan MAC represents a “land in-between” due to its historical “independence” from both the Chinese and Tibetan empires; but when considering historical sources, local rulers kept rather loyal to the imperial courts of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, especially during the transformation of the local autonomous rulers into the position of qinwang during the Qing Empire. Then, after the incorporation into the centralized modern Chinese State, the qinwang position was transformed into a position as a local county governor.

This paper shed light on the local political leading figure, the last qinwang and the first county governor named Tashi Tsering. In official records, documents for internal use, as well as in her (re)presentation in the Mansion, Tashi Tsering – victim of the Cultural Revolution, but posthumously rehabilitated – is the local “ethnic heroine” and a symbol for the local “Mongolness”. Moreover, she is one of the reasons why most of Henan MAC’s population refer to their Mongol identity. In fact, the community’s sense of history is a powerful component for the construction of their identity. Images from the past legitimate the affiliation to a group and/or ones’ social status even more intensely, and additionally, ancestral links – even fictive ones – play an important role to prove the group’s or individual’s status.

The primary event in the collective memory of the Henan Mongols is the incorporation of the Henan grasslands into the Qing Empire after the rebellion of 1723 and Tsagan Tenzin became their first qinwang . This “princely” authority, up until the incorporation into the Chinese State in 1954, is kept alive in the memory of the Henan Mongols. In terms of the people of the Henan grasslands, the Mansion museum and the stupa in the Main Assembly Hall of Labrang monastery are contested as places of memory. When the Henan Mongols try to reconstruct memory in their narrative, they hardly refer to the Henan MAC but to the Mengqi (Mongol Banners) and the qinwang – or with the Tibetan colloquial term rgyal mo – as their leading figure. Tashi Tsering was the last qinwang , who continues to be celebrated as a local “heroine” and the symbol of “Mongolness”. These rare attributes for a politically emancipated woman might have helped Tashi Tsering to manipulate the system (and the people) to her own advantage and might have made her a “heroine” due to her goodness and beauty.

By having discovered their Mongol roots as a means to distance themselves both from the Han Chinese and the Tibetans, it implies that the Henan Mongols have adapted to and complied with national policies. But, at the same time, they identify themselves based on (historical) sociopolitical experiences, and on local heritage. In sum, by using culture or culture-related issues for developing ethnic consciousness, Henan Mongols came to realize that when sharing at least a collective, cultural identity, political and material benefits can be derived from that. It further shows that identity requires negotiation with the other; one needs to be aware of the past. Their attempt at a collective memory and identity was supported by political propaganda, the results of the civilizing projects financed by the centralized State.

Huang Shihe (ed.). Yum chen Klu sman Mtsho. Lanmancuo [ 黄世和。兰曼措 ]. The Great Mother Klu Man Tsho. Lanmancuo. Xian, Qinghai Henan mengguzu zizhixian zhengxie, 2008, 92 p. (in Chin. and Tib.)

Huang Zhengqing. A blo spun mched kyi rnam thar [Biography of A Pa Alo]. Beijing, Minzu chu-banshe, 1994, 345 p. (in Tib.)

Kato N. Lobjang Danjin’s Rebellion of 1723: With a Focus on the Eve of the Rebellion. Acta Asia-tica , 1993, vol. 64, pp. 57–80.

Khan A. Chinggis Khan: From Imperial Ancestor to Ethnic Hero. In: Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers. Seattle, Uni. of Washington Press, 1995, pp. 247–277.

Nietupski P. Labrang Monastery. A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709–1958. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2011, 306 p.

Petech L. Notes on Tibetan History of the 18th Century. T’oung Pao , 1966, vol. 52, no. 4/5, pp. 261–292.

Perdue P. C. China Marches West. The Qing Conquest of China. Cambridge, Harvard Uni. Press, 2005, 725 p.

Rock J. F. The Amnye Ma-Chen Range and Adjacent Region. Rome, Institutio Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1957, 194 p.

Rohlf G. Building New China, Colonizing Kokonor. Resettlement to Qinghai in the 1950s. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2016, 308 p.

Romanovsky W. Die Kriege des Qing-Kaisers Kangxi gegen den Oiratenfürsten Galden. Wien, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1998, 289 p.

Sa Renna. Shehui hudong zhong de minzu rentong jiangou – Guanyu Qinghai sheng Henan Meng-guzu rentong wenti de diaocha baogao [ 萨仁娜。社会互动中的民族认 同建构 – 关于青海省

河南蒙古族认同问题的调查报告 ] Social Interaction in Terms of the Ethnic Identity Issue. A Field Report of Henan Mongols in Qinghai. Beijing, Zhongyang minzu daxue chubanshe, 2011, 193 p. (in Chin.)

Shi Lun. Xibei Ma jiajun fa shi [ 师纶。西北马家军阀史 ] The Powerful History of the Ma Warlords. Lanzhou, Gansu renmin chubanshe, 2007, 448 p. (in Chin.)

Sneath D. Changing Inner Mongolia: Pastoral Mongolian Society and the Chinese State. Oxford, Oxford Uni. Press, 2000, 320 p.

Roche G. The Tibetanization of Henan’s Mongols: Ethnicity and Assimilation on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier. Asian Ethnicity , 2015, vol. 17, pp. 128–149.

Wallenböck U. Marginalisation at China’s Multi-Ethnic Frontier: The Mongols of Henan Mongolian Autonomous County in Qinghai Province. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs , 2016, vol. 45, pp. 149–182.

Wallenböck U. Cultural and Educational Dimension of the “Silk Road”: The Re-invention of Mon-golness in Qinghai Province, PR China. Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies , 2019a, vol. 11, pp. 31–59.

Wallenböck U. Die Bevölkerung am Sino-Tibetischen Grenzgebiet. Identitätskonstruktion der Ti-bet-Mongolen. Münster, Aschendorff Verlag, 2019b, 272 S.

Yang Ho-chin. Annals of Kokonor by Sumpa Khenpo Yeshe Paljor. Bloomington, Indiana Uni. Press, 1967, 125 p. (Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 106)

Zhuocang Cairang (ed.). Huang He Nan Menggu Zhi [ 卓仓才让。黄河南蒙古志 ]. Annals of the Mongols South of the Yellow River. Lanzhou, Gansu minzu chubanshe, 2010, 584 p. (in Chin.)

Список литературы Memory and identity: Tashi Tsering, the last qinwang south of the Yellow river

- Chen Zhongyi, Zhou Ta. Labulengsi yu Huangshi jiazu [陈中义, 洲塔。拉卜楞寺与黄氏家族] Labrang Monastery and the Huang Family. Lanzhou, Gansu renmin chubanshe, 1995, 410 p. (in Chin.)

- Dhondup Y., Diemberger H. Tashi Tsering: The Last Mongol Queen of Sogpo (Henan). Inner Asia, 2002, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 197-224.

- Delhey M. Views on Suicide in Buddhism: Some Remarks. In: Buddhism and Violence. Lumbini, Lumbini International Research Institute, 2006, pp. 25-64.

- Denton K. A. Museums, Memorial Sites and Exhibitionary Culture in the People's Republic of China. In: China Quarterly 183 Culture in the Contemporary PRC, 2005, pp. 565-586.

- Denton K. A. Exhibiting the Past. Historical Memory and the Politics of Museums in Postsocialist China. Honolulu, Uni. of Hawai’i Press, 2014, 360 p.

- Diemberger H. Introduction: Mongols and Tibetans. Inner Asia, 2002, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 171-180.

- Diemberger H. Festivals and Their Leaders: The Management of Tradition in the Mongolian / Tibetan Borderland. In Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS, 2003, vol. 9: The Mongolia-Tibet Interface, Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia. Leiden, Brill, 2007, pp. 109-128.

- Guomaoji. Qianxi ‘modai nu qinwang’ Zhaixi Cairang [果毛吉。浅析 末代女亲王 扎喜才让] Elementary Analyzes in the Last Mongolian Female Qinwang Tashi Tsering. Sichuan minzu xueyuan xuebao 2011, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 21-24. (in Chin.)

- Gyatso J., Havnevik H. (eds.). Women in Tibet. New Delhi, Foundation Books, 2005, 352 p.

- Halbwachs M. Das Kollekti e Gedachtnis und Seine Sozialen Bedingungen. Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1985, 398 S.

- Han Xinhua (ed.). Fengfan changcun. Qinghai Henan Mengqi qinwang Zhaxi Cairang shiliao xuan [韩新华。风范长存 - 青海河南蒙旗亲王扎喜才让史料选]. Merits Forever. Selected Historical Materials on Qinghai Henan’s qinwang Tashi Tsering. Xining, Qinghai sheng zhengxie xuexi he wenshi weiyuanhui, 2006, 204 p. (in Chin.)

- Henan Mengguzu zizhixian gaikuang [河南蒙古族自治县概况]. A Survey of Henan Mongol Autonomous County. Beijing, Renmin chubanshe, 2009, 132 p. (in Chin.)

- Henan Xian zhi [河南县志] Annals of Henan County. In 2 vols. Lanzhou, Gansu renmin chubanshe, 1996, 1096 p. (in Chin.)

- Huang Shihe (ed.). Yum chen Klu sman Mtsho. Lanmancuo [黄世和。兰曼措]. The Great Mother Klu Man Tsho. Lanmancuo. Xian, Qinghai Henan mengguzu zizhixian zhengxie, 2008, 92 p. (in Chin. and Tib.)

- Huang Zhengqing. A blo spun mched kyi rnam thar [Biography of A Pa Alo]. Beijing, Minzu chubanshe, 1994, 345 p. (in Tib.)

- Kato N. Lo jang Danjin’s Re ellion of 1723: With a Focus on the Eve of the Rebellion. Acta Asiatica, 1993, vol. 64, pp. 57-80.

- Khan A. Chinggis Khan: From Imperial Ancestor to Ethnic Hero. In: Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers. Seattle, Uni. of Washington Press, 1995, pp. 247-277.

- Nietupski P. Labrang Monastery. A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709-1958. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2011, 306 p.

- Petech L. Notes on Tibetan History of the 18th Century. T’oung Pao, 1966, vol. 52, no. 4/5, pp. 261-292.

- Perdue P. C. China Marches West. The Qing Conquest of China. Cambridge, Harvard Uni. Press, 2005, 725 p.

- Rock J. F. The Amnye Ma-Chen Range and Adjacent Region. Rome, Institutio Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1957, 194 p.

- Rohlf G. Building New China, Colonizing Kokonor. Resettlement to Qinghai in the 1950s. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2016, 308 p.

- Romanovsky W. Die Kriege des Qing-Kaisers Kangxi gegen den Oiratenfursten Galden. Wien, Osterreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1998, 289 p.

- Sa Renna. Shehui hudong zhong de minzu rentong jiangou - Guanyu Qinghai sheng Henan Mengguzu rentong wenti de diaocha baogao [萨仁娜。社会互动中的民族认 同建构 - 关于青海省河南蒙古族认同问题的调查报告] Social Interaction in Terms of the Ethnic Identity Issue. A Field Report of Henan Mongols in Qinghai. Beijing, Zhongyang minzu daxue chubanshe, 2011, 193 p. (in Chin.)

- Shi Lun. Xibei Ma jiajun fa shi [师纶。西北马家军阀史] The Powerful History of the Ma Warlords. Lanzhou, Gansu renmin chubanshe, 2007, 448 p. (in Chin.)

- Sneath D. Changing Inner Mongolia: Pastoral Mongolian Society and the Chinese State. Oxford, Oxford Uni. Press, 2000, 320 p.

- Roche G. The Tibetanization of Henan’s Mongols: Ethnicity and Assimilation on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier. Asian Ethnicity, 2015, vol. 17, pp. 128-149.

- Wallenböck U. Marginalisation at China’s Multi-Ethnic Frontier: The Mongols of Henan Mongolian Autonomous County in Qinghai Province. Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 2016, vol. 45, pp. 149-182.

- Wallenböck U. Cultural and Educational Dimension of the Silk Road : The Re-invention of Mongolness in Qinghai Province, PR China. Vienna Journal of East Asian Studies, 2019a, vol. 11, pp. 31-59.

- Wallenböck U. Die Bevölkerung im Sino-Tibetischen Grenzgebiet : Identitätskonstruktion der Tibet-Mongolen. Münster, Aschendorff Verlag, 2019b, 272 S.

- Yang Ho-chin. Annals of Kokonor by Sumpa Khenpo Yeshe Paljor. Bloomington, Indiana Uni. Press, 1967, 125 p. (Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 106)

- Zhuocang Cairang (ed.). Huang He Nan Menggu Zhi [卓仓才让。黄河南蒙古志]. Annals of the Mongols South of the Yellow River. Lanzhou, Gansu minzu chubanshe, 2010, 584 p. (in Chin.)