Military-Political Situation in the Arctic: Hotspots of Tension and Ways of De-Escalation

Автор: Zagorskiy A.V., Todorov A.A.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Political processes and institutions

Статья в выпуске: 44, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article describes the politico-military situation in the Arctic, including the development of military capabilities of states in the region, the coastal infrastructure, the scales and the manner of military exercises, as well as the dynamics of the military landscape in the Arctic. The authors argue that the military capabilities in most parts of the Arctic remain moderate, primarily due to harsh climate restraints. However, military activity both of NATO member-states and Russia has increased considerably recently in the Euro-Arctic area adjacent to the North Atlantic, in particular in the waters of the Barents and the Norwegian seas. Mutual military deterrence in this area represents a "new old" normal that will shape the security situation in the Arctic in the long term. The article concludes by considering possible options for preventing escalation and minimizing the concerns of the sides by restoring a full, regular and institutionalized military dialogue between Russia and the rest of the Arctic states.

Arctic, Russia, USA, Arctic state, NATO, security, military-political landscape

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148322045

IDR: 148322045 | УДК: 327(045) | DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2021.44.79

Текст научной статьи Military-Political Situation in the Arctic: Hotspots of Tension and Ways of De-Escalation

In recent years, the nature of the discussion on possible conflict scenarios in the Arctic has changed. Predictions that there are reasons for future conflicts in the region in struggle for the “division” and “redistribution” of the Arctic spaces, resources and shipping routes have proved to be a strong exaggeration [1, Spohr K., p. 64, 123, 210, 226, 361]. However, after the Trump administration (2017–2021) based its national security doctrine on the thesis of the global rivalry between the United States and China and Russia, the question of how such rivalry would affect the military and political situation in the Arctic came into focus [2, Humrich Ch., p. 99–102]. The region today is often viewed as one of the arenas in which the struggle between the United States, Russia and China for global domination will unfold [3, Huebert R.]. In 2019, this thesis was included in the Arctic strategies of the US Coast Guard 1 and the Department of Defense 2. It formed the basis of the Arctic strategy of the US Air Force (Air Force) 3, announced in the summer of 2020, and the

updated Arctic strategy of the Naval Forces (Navy) 4 and the US Army (Ground Forces) 5 in January 2021, on the eve of J. Baden's inauguration. The conclusion about growing competition between the leading nations in the region is also shared by the Russian military department 6.

Early signals from the new US administration suggest that military security issues are not at the top of its Arctic agenda. Although Biden is not expected to revise Trump's decisions to partially expand the US presence in the Arctic, the new president does not seem inclined to subject his policy in the region solely to the logic of confrontation with China and Russia and to invest heavily in military construction 7.

In May 2021, cooperation on “peaceful, sustainable economic development and environmental protection in the Arctic” was included by the G7 foreign ministers in a short list of issues on which they are ready to interact with Russia 8. The speech of Secretary of State E. Blinken at the ministerial session of the Arctic Council in Reykjavik on May 20, 2021 9, which contrasted sharply with the scrappy speech of his predecessor M. Pompeo in Rovaniemi two years earlier, may indicate Washington's cautious departure from the harsh Arctic rhetoric of the Trump administration.

This tendency, however, may turn out to be unstable against the background of alarmist narratives that still dominate the political discourse 10. Both in the West and in Russia, the emphasis is on the most threatening scenarios for the development of military-political situation in the region. Western media are full of reports about testing of the Russian nuclear-powered unmanned submarine carrier “Poseidon”, test launches of the hypersonic missile “Zircon” in the Northern Fleet, Russian icebreakers armed with missiles, large-scale Russian military construction in the Arctic, etc. All this is presented as a manifestation of Russia's desire to dictate its own rules in the Arc- tic Ocean. China is credited with ambitions to challenge the Arctic countries, and, if necessary, with the use of force 11.

Russia is paying attention to the growing intensity and scale of military trainings of the US Navy and NATO in the Arctic region, approaching closer to the borders of the Russian Federation 12. The US and NATO naval exercises military ships trainings in the Barents Sea since 2020 13, Norway's decision to allow the US nuclear submarines to use the port of Tromsø in the north of the country [4, Anthony I., Klimenko E., Su F., p. 15], temporary deployment of four B-1B Lancer bombers at the Orland air base in the south of the country in February 2021 are regarded by Russia as provocative 14. The Fundamentals of Russian State Policy in the Arctic, approved in March 2020, notes “a foreign military presence” and “an increase of conflict potential in the region” as one of the challenges to the country's national security 15.

The situation is complicated by the “freezing” of military cooperation with Russia by the Arctic countries since 2014. The lack of channels of regular communication between the militaries at various levels makes it impossible to discuss and resolve emerging concerns, including by agreeing on mutual restraint measures.

In order to maintain and strengthen the trend towards constructive cooperation within the framework of the Arctic agenda, it seems important to solve two problems as a first step. The first one is a sober assessment of the military-political situation in the Arctic . The IMEMO RAS uses the following parameters for its monitoring [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 20]:

-

• states’ deployment of military assets in the region on a permanent basis ;

-

• availability of assets for temporary (seasonal) deployment in the Arctic;

-

• construction of coastal infrastructure for basing and ensuring operational stability of deployed or temporarily deployed assets in the Arctic;

-

• dynamics of military exercises in the region: their frequency , scope and scenarios .

At the same time, it is important to differentiate the conditions for non-strategic (conventional) military activity in different parts of the Arctic. They differ significantly in the colder Amer-asian and central parts of the Arctic Ocean, constituting the major part of the region, and in the warmer (albeit also complex) “Euro-Arctic” seas adjacent to the North Atlantic [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 33; 1, Spohr K., p. 343].

The second task is to resume channels of regular communication between representatives of military departments at all levels to exchange assessments of the operational situation in the region and discuss measures to de-escalate not only military activity, but also rhetoric.

The first section of this article examines the military development programs implemented by the states of the region in the “big” Arctic, plans for the coastal infrastructure development, the scale and nature of military exercises, and the results of the defense policy review conducted by the Arctic states since 2014. In the second section, the dynamics of the military-political situation in the Euro-Arctic region is considered, and the third focuses on the possibilities for developing risk mitigation mechanisms, to be formed mainly in the “Euro-Arctic” part of the region.

Non-strategic forces in the “big” Arctic

With the exception of the Russian Federation, the Arctic states do not permanently deploy non-strategic combat forces in the region . For Russia and the United States, the Arctic is of particular importance mainly in the context of maintaining the strategic balance of nuclear deterrence. Most of the Russian naval strategic nuclear forces are based on the Kola Peninsula as part of the Northern Fleet. Russian and American anti-missile, anti-aircraft and anti-submarine defense facilities, and the US missile attack warning radar system are deployed in the region. In recent years, in the context of the return of Russia and NATO to the policy of mutual military deterrence in Europe, the military-political importance of the Arctic waters adjacent to the North Atlantic has increased.

Due to the harsh natural and climatic conditions, remoteness, underdevelopment of coastal infrastructure and other circumstances, non-strategic military construction in the “big Arctic” is considered not only costly, but also impractical. Climate change does not reduce, but rather increases the risks associated with military (and any other) activities in most of the marine and land Arctic, not only in winter, but also in summer [6, Soldatenko S.A., Alekseev T.V., Ivanov N.E. et al., p. 57–60; 7, Konovalov A.M., p. 139; 8, Christensen K.D.; 9, Balasevicius T., p. 25–26]. This circumstance is emphasized in the documents of the military authorities of the Arctic countries 16.

While in winter the naval activity in the region is hampered by the ice cover, during the period of its melting in summer and autumn navigation is complicated by poor visibility, the danger of collision with drifting ice floes and icing, and many other factors 17.

During the most favorable period for Arctic navigation, many naval ships can be temporarily deployed in the Arctic seas and navigate through “clear water” up to the ice edge at low speed, avoiding collisions with drifting ice. During this period — from July to October — ships of the Northern Fleet make voyages along the water area of the Northern Sea Route. Nevertheless, the optimal solution for the implementation of regular surface naval activities and autonomous navigation in the Arctic is the construction of special ice-class ships. In order to ensure the operational sustainability of this activity, large-scale investments are required in the construction of coastal infrastructure, logistics and supply system for the fleet, communications, a large amount of hydrographic and cartographic work [10, Forget P.] 18.

Building special ships for the Arctic is not just costly. In terms of their tactical, technical and operational characteristics — speed, maneuverability, energy efficiency and others — they are inferior to modern naval ships, and their use outside the Arctic region is considered ineffective and inexpedient 19.

It is not surprising that the number of warships that the Arctic states could temporarily deploy in the region is extremely limited (non-Arctic countries have none at all 20). The Danish Navy has four ice-reinforced Tethys-class patrol frigates built in the early 1990s. On a rotational basis, frigates patrol the waters of Greenland and the Faroe Islands, solving the tasks of the coast guard. In 2008–2017, the Danish Navy replaced three Agdlek-class patrol ships with Knud Rasmussen-class ships patrolling in the territorial sea of Greenland [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 91].

Canada is lagging significantly behind schedule in implementing the 2008 program to build six Gary De Wolfe-class Arctic patrol ships with light ice reinforcements for the Navy, capable of breaking ice up to 1.2 m thick. Based in the south of the country in Halifax, they will be deployed in Arctic latitudes from July to October for missions similar to those of the Coast Guard. The first ship of this series was commissioned the Canadian Navy in the summer of 2020. The program is planned to be completed in 2025 21.

In 2017, an icebreaker of the Ilya Muromets-class came online in the Russian Northern Fleet, and in 2019 — the patrol ship Ivan Potanin, comparable in its characteristics with the Danish frigates Tetis [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 60].

The Norwegian Navy does not have ice-reinforced ships, but there are five Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates and six Ula-class diesel-electric submarines that can be deployed in the ice-free waters of the Norwegian and Barents Seas [12, Wezeman S.T., p. 12–13]. The U.S. Navy also has no ships with ice reinforcements. Until recently, they have refused to build them, citing their high cost and inexpediency, given the low level of military threats in the Arctic 22. Despite the change in the tonality of the US Navy's Arctic strategy 2021, the issue of building ice-class ships is not raised in it.

There are ships with icebreaking capabilities in the Coast Guard of Canada, Norway and Russia. In 2019, the United States decided to replace two old Coast Guard icebreakers, built in 1976–1978, with three new ones (“Polar Security Cutters”). The first of them should be built in 2024. The long term plan is to build a total of six new icebreakers for the US Coast Guard 23.

With the exception of Russia, Arctic naval warships that could be deployed in polar waters are not permanently based in the region and cannot “operate” in the Arctic year-round. The analysis of the planned defense policy reviews conducted by the Arctic countries after 2014 has shown that none of them have revised their previously adopted modest military construction programs in the region upwards [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 96–103].

In the greater (freezing) part of the Arctic region, there is practically no coastal infrastructure that could ensure the operational stability of seasonal naval activities, not to mention the permanent deployment of naval forces and assets in the region. Moreover, melting permafrost, storms and erosion of the coastline threaten existing and impede the construction of new coastal infrastructure 24.

However, in 2021, the United States approved a plan to build a deep-water port in Nome on the Pacific coast of Alaska 25. Located about 250 km south of the Bering Strait, the port, which freezes from November to May, has for many years been considered as the northernmost point for the possible construction of a deep-water port to ensure the safety of navigation in the region and the potential basing of US Coast Guard patrol ships (their main base is located in the port of Dach Harbor on the Aleutian islands, and the Coast Guard icebreakers are based on the west coast of the United States in Seattle). Nome could potentially be used for the temporary deployment of warships in US Arctic waters, which is envisaged in the Navy's plans as a long-term prospect. A ship supply station was established in northern Canada in Nanisivik, Nunavut province, in accordance with a program approved in 2008 [12, Wezeman S.T., p. 7] 26. This, in fact, limits infrastructure projects (not including Russian ones) in the “big” Arctic.

Neither Denmark nor Canada has permanently stationed ground forces in the region, although it is possible to deploy them temporarily if necessary. A few troops and subdivisions of the Norwegian armed forces are evenly distributed over the territory of the country [5, Zagorskiy AV, p. 76–78, 81, 83]. The United States does not have military bases beyond the Arctic Circle, but there are three US Army bases in southern Alaska, in the subarctic zone — Fort Wainwright, Fort Greeley and the joint Elmendorf-Richardson Air Force base. 11600 servicemen are permanently stationed in two brigades. These forces are part of the Indo-Pacific Command of the United States, while the Northern Command, which is responsible for Alaska, does not have its own forces and assets there 27. The US Army's Arctic Strategy 2021 outlined the prospect of creating a headquarters structure and a task force in Alaska that could be deployed in different regions of the world with similar climatic conditions 28.

After the end of the Cold War, the Norwegian ground forces were reduced to a single mechanised brigade “Nord”, which includes two mechanised battalions and a light infantry battalion. The brigade is located mainly in the central part of the Troms province, north of the Arctic Circle [12, Wezeman S.T., p. 11] 29. Against the background of the growing crisis in in Russian-Western relations and a return to mutual military deterrence, the most heated discussion of plans for military construction after 2014 took place in Norway.

During the planned review of the country's defence policy in 2015–2016 and 2019–2020, the General Staff, referring to the change in the security situation in the country, suggested a significant strengthening of the armed forces. It was proposed, in particular, to double the size of the armed forces, to create a second brigade of ground forces, concentrate them in the north of the country and increase the level of combat readiness, significantly increase the number of tactical aircraft, patrol aircraft, air defense systems, tactical helicopters and helicopters for the Navy, purchase an additional new submarine and two frigates 30.

However, in the long-term military plans for 2016 and 2020, the ambitious proposals of the General Staff were largely rejected, and the approved plans are even more modest than the previous ones. Instead of a significant build-up of a permanent military presence in the north, the Norwegian government has focused on modernising early warning capabilities on the one hand, and on developing a reinforcement infrastructure with NATO countries (temporary deployments) in a threat period on the other 31.

Since 2014, there has been little change in the scope of military exercises conducted by the Arctic states in the region, but the nature of the exercises has changed .

The largest exercise, held annually in the Canadian Arctic since 2007 (Operation Nanook), is practicing the interaction of the military and civilian agencies in emergencies. The maximum number of participants in these studies was registered in 2010–2012. Against the background of the crisis in Russia's relations with the West, the scenarios, intensity and nature of the exercises conducted in northern Canada have not changed 32. The country's 2019 Arctic strategy announced a revision of the “Operation Nanook” concept 33. However, in 2020 and 2021, their scale was reduced due to the pandemic 34.

The main winter combat training for the Norwegian Armed Forces since 2006 is the Cold Response exercise. Since 2010, they have been held every two years instead of annually. Invitations to participate are sent to NATO countries, as well as Finland and Sweden. The number of military personnel which took part in the Cold Response did not increase after 2014. Some increase was expected in 2020, but the exercises had to be canceled due to the pandemic [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 104–107] 35.

However, the nature of the exercises in Norway has changed in recent years. While previously the Cold Response scenarios were focused on increasing the level of interoperability and practicing interaction skills as part of multinational formations participating in international crisis management operations, today’s scenarios are based on the possibility of a crisis situation in the North of Europe requiring the redeployment of NATO allied forces to Norway under Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. This scenario was also the basis for the NATO Trident Juncture exercise, which took place in autumn 2018 in Norway and the North Atlantic. They were attended by about 50 thousand servicemen of 31 states (29 NATO countries, Finland and Sweden), 250 combat aircraft, 65 warships, about 10 thousand combat vehicles [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 107].

These exercises are cited as an example of building up the scale of NATO's military activities in northern Europe 36. However, they were not a regular event of combat training in the region. Such exercises were conducted by NATO every three years in different regions of Europe. Today they have been replaced by the Defender of Europe, an exercise that focuses on the redeployment of forces from the U.S. to Europe. The 2022 Cold Response exercise may set a new scale for Norwegian combat training. It is expected to be the largest since the end of the Cold War 37. It should be assumed that in the future, temporary Allied deployments to Norway will become the norm. However, this does not imply a permanent deployment of alliance forces in the country.

The US European Command does not conduct independent exercises in northern latitudes, but participates in combat training events organised by the Nordic countries — Cold Response, the Arctic Challenge Regional Air Force Exercise, and others. The Indo-Pacific Command has regularly conducted tactical exercises “Northern Edge” in sub-arctic latitudes in the Gulf of Alaska since 1993. In the early 1990s, they were attended by from nine up to fifteen thousand servicemen, in the 2000s — up to nine thousand 38. In 2015, the Northern Edge exercise involving 6000 military personnel worked out a scenario for responding to a crisis situation in the Asia-Pacific region. The US Northern Command, in cooperation with the Coast Guard, organizes the SAREX exercise in Alaska on the interaction of the armed forces, the coast guard and civilian authorities in the course of search and rescue operations [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 108–109] 39.

In recent years, the nature of military training activities conducted by the United States in the northern latitudes has changed. For the first time in three decades, the Northern Edge exer- cise scenario in 2018 envisaged organization of defensive actions in low Arctic temperatures. About 1500 military personnel took part in practical shooting exercises at the Indo-Pacific Command ranges on the southern coast of Alaska 40. With the adoption of the US Army’s Arctic strategy in 2021, such exercises are likely to become regular.

In 2019, the US Navy conducted the first “Arctic expeditionary potential” exercises announced in the 2019 US Department of Defense's Arctic strategy, on the southern coast of Alaska with the use of Coast Guard bases in the Aleutian Islands. About three thousand marines took part in it 41. The US Navy's multi-purpose submarine patrolling in the Arctic Ocean became more intensive. In 2018, a British submarine conducted joint exercises with the US Navy in the western part of the Arctic Ocean. In May 2020, for the first time since the 1980s, a five-day exercise of the US and British navies took place in the Barents Sea [1, Spohr K., Hamilton D.S., p. 202–203] 42, and in September 2020 — joint exercises of ships of Denmark, Norway, Great Britain and the United States 43.

Based on this review, it can be concluded that the Arctic NATO member states

-

• do not deploy significant combat forces in the Arctic on a permanent basis;

-

• do not invest heavily in the construction of coastal infrastructure in the region;

-

• change the nature of their exercises, taking into account the return to the policy of containment of Russia, although until recently they did not increase their scale and intensity.

The United States, whose military presence in the Arctic until recently was practically minimal, made a choice in favor of the gradual formation of a potential for the temporary deployment of forces and assets in the Arctic latitudes.

This picture will be incomplete without taking into account the intensification of Russia's military activity in the Arctic in the last decade. In 2012, for example, in Pechenga District of Murmansk Oblast and in the Barents Sea, an inter-service command post exercise involving over seven thousand servicemen, over 20 surface ships and submarines was conducted. In 2013, a large-scale exercise by the Pacific Fleet ended with an amphibious assault landing on the coast of Provideniya Bay. The operation was attended by about three thousand military personnel, more than ten ships and support vessels. In 2015, 38 thousand servicemen, 3360 units of military equipment, 41 warships, 15 submarines, 110 aircraft and helicopters were involved in a snap check of the combat readiness of the Arctic group of forces, individual formations of the Western Military District and the airborne troops. From July to September 2016, monthslong exercises were held in the Northern Fleet. In 2018, a Northern Fleet detachment consisting of 36 surface ships, submarines and support vessels made a transarctic transition from the Barents Sea to the Bering Sea and back. In 2019, during a two-month long-distance cruise of a detachment of warships and support vessels of the Northern Fleet, more than ten large-scale exercises were held at sea and on land [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 109–112]. In August 2020, the forces of the Pacific Fleet took part in the Ocean Shield naval exercise. In the water area of the Bering Sea, on the Chukotka Peninsula and in Kamchatka, 30 warships and support vessels, more than three thousand servicemen were involved 44. The Northern Fleet is carrying out an intensive training programme in 2021 45.

Political-military dynamics in the Euro-Arctic region

The changes in the politico-military situation outlined above are characteristic primarily for the Euro-Arctic part of the region, adjacent to the North Atlantic, and less significant in the “Am-erasian” Arctic and the central part of the Arctic Ocean. This is due to a number of circumstances.

Firstly, difficult natural and climatic conditions, high military construction costs and the seasonal nature of ice cover retreat continue to limit regular military activities in most of the Arctic region. In the summer-autumn period, the greatest losses of sea ice are observed in the East Siberian Sea and significant losses are in the Kara, Laptev, Chukchi and Beaufort seas, then in winter the main losses of the ice cover are in the Barents Sea, while the main part of the Arctic Ocean is covered with ice 46. The Barents and Norwegian Seas are the most accessible for various activities, including military ones. The coastal infrastructure is more developed here, the population density is higher 47. But a significant part of the Arctic Ocean waters for the foreseeable future for most of the year will remain inaccessible even for the temporary deployment of surface forces 48. The boundaries of the Arctic, which differ in their natural and climatic conditions, may serve as a conventional boundary for applying the provisions of the Polar Code, which contains requirements for ships navigating in polar waters (Fig. 1).

Secondly, the main arena of mutual military deterrence between Russia and NATO is Europe and the North Atlantic. The Arctic seas adjacent to the North Atlantic — the Norwegian and the Barents seas — are today, as during the Cold War, an integral part of this activity. For this reason, many of the alliance's decisions in recent years have had an impact on the politico-military situation in the Euro-Arctic, although the increase in military activity there lags significantly behind its scale in the Baltic and the Black Sea. The region is given special significance by the fact that Russian strategic submarines with ballistic missiles on board are based on the Kola Peninsula, and any intensification of military activities by the United States and NATO countries in the Barents Sea cannot but cause concern in Russia.

Fig. 1. Boundaries of the application of the Polar Code provisions 49.

The main decisions of recent years, adopted by Western countries in the broader context of Russian military deterrence and affecting the Euro-Arctic region, include the following.

The policy of deterring Russia on NATO's eastern flank in the Baltic region does not presuppose the permanent deployment of significant military forces there, but building infrastructure and reinforcement capabilities by transfer forces from other alliance states and the United States. The same approach is applied in Northern Europe [4, Anthony I., Klimenko E., Su F., p. 14], primarily in Norway. The task of strengthening the Norwegian forces was practiced in 2018 during the Trident Junction exercise and served as the basis of future scenarios for the Cold Response exercise.

In order to ensure the redeployment of troops from the United States to Europe in 2018, it was decided to replace the NATO Atlantic Command that was disbanded in 2002 with two new structures: the Joint Atlantic Command (Norfolk, USA) and the Joint Logistics Command in Germa-

Source: International Maritime Organization.

ny. The US Second Fleet , disbanded in 2011, was reconstituted in 2019 to ensure the safety of transatlantic sea communications [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 46]. Its area of responsibility includes the North Atlantic and the Euro-Arctic seas — the Norwegian and Barents 50.

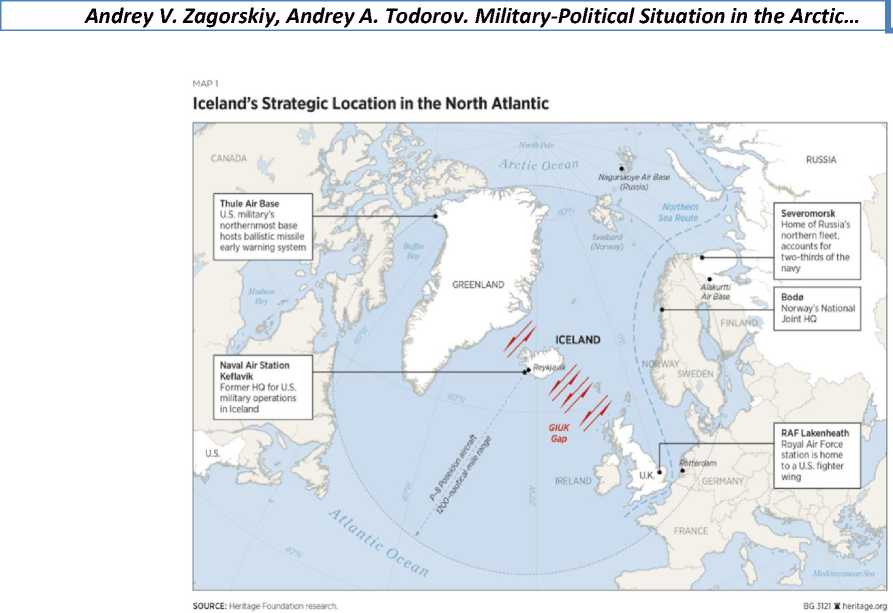

The anti-submarine Greenland – Iceland – UK gap (GIUK) is being restored (Fig. 2), which during the Cold War was supposed to prevent Soviet Northern Fleet nuclear submarines from entering the North Atlantic in the event of a crisis. For this purpose, the U.S. decided to upgrade the airstrip at its base in Thule, Greenland, which until recently had been used solely for the radar of the American missile attack warning system 51. The Keflavik air base in Iceland, which the US has not used since 2006, was upgraded to serve as a base for anti-submarine, transport and fighter aircraft of NATO countries. A maritime operations centre will be created there in 2019 and will work in close cooperation with the US Second Fleet 52. The decisions on strengthening the antisubmarine defence forces of Denmark and Norway, renewal of the military planning of the UK for the Euro-Arctic region [11, Todorov A.A., Lyzhin D.N., p. 88–90] 53, including the decision of London to procure new anti-submarine warfare aircraft (in 2010, the UK gave up the old ones) fit into the logic of rebuilding the North Atlantic waterfront 54. The expediency of such measures is justified by the resumption of Russian submarines’ cruises in the North Atlantic.

With the restoration of the anti-submarine line in the Norwegian Sea, the alliance's annual anti-submarine exercises with the participation of multipurpose submarines and GMW destroyers “Swift Mongoose”, which have been held since 2012 in the North Sea, have shifted 55. In April 2021, Norway and the United States signed an additional agreement on defense cooperation, which will enable the United States to use the Norwegian Air Force facilities after modernization in the south and north of the country for the temporary deployment of R-8 anti-submarine aircraft and B-1 bombers, as well as the base Ramsund Navy to service US ships and submarines 56.

.

Fig. 2. The anti-submarine line Greenland — Iceland — Great Britain 57

It is not a question of permanently deploying US forces and assets in Norway (in 2020, it was reported about the withdrawal from the country's territory of the US Marine Corps battalion, which was deployed in 2017 to ensure the American troops redeployment to participate in the exercises 58), but about the possibility of their temporary deployment. At the same time, the EuroArctic territories and water areas are viewed in the United States and NATO not as an independent space, but as a continuation and component of the North Atlantic area of naval activity .

The same can be said for the Russian Northern Fleet. In addition to solving the main tasks of ensuring the operational stability of the country's naval strategic forces based on the Kola Peninsula, it has always been focused on actions in the North Atlantic, not in the Arctic 59. Limited tasks to protect the interests of the Russian Federation in the Arctic zone appeared in its portfolio quite recently. The most intensive combat training activities of the Northern Fleet forces both in winter and in summer are held in the waters of the Barents, Norwegian and White Seas , and lately in the North Atlantic as well. So, in 2019, the forces of the Northern Fleet were for the first time represented on a large-scale basis in the Ocean Shield inter-fleet exercise in the waters of the Northern and southern parts of the Norwegian Seas, which involved more than 4.5 thousand military personnel, over 20 warships, submarines and support vessels, up to 20 aircraft and helicopters of anti-submarine, fighter and bomber aviation 60.

Against this background, the main change in the military-political situation in the Arctic lies in the intensification of military activity in the mutual intersection zone of the operational areas of

the Russian Northern Fleet and the US Second Fleet in the Barents and Norwegian Seas, as well as in the North Atlantic . So far, the intersection of their activities has not reached a critical scale, but as it intensifies, the risks of dangerous military incidents at sea and in the air, as well as their escalation, increase.

De-escalation options

A broad consensus has long been formed in the expert community regarding the need to resume the military contacts interrupted in 2014 in the interest of de-escalating the militarypolitical situation in the region. Various solutions have been proposed as to how this could be done. In most cases, some form of Arctic forum with military representatives from the Arctic countries to discuss the politico-military situation and agree on confidence-building measures in the region has been proposed 61. However, practical steps in this direction have not yet been agreed at the intergovernmental level. It seems important to take into account three aspects of this issue when discussing possible de-escalation measures.

First, it should be assumed that the policy of mutual military deterrence is a “new old” norm that will determine the military-political situation in the North Atlantic and the Euro-Arctic region in the long term, regardless of possible fluctuations in the political situation between Russia and the West. In other words, the refusal of the parties to implement the decisions they have made in recent years, which changed the military-political situation in the region for the worse, is not on the agenda today. Although the scale of mutual deterrence today is far from the scale of the Cold War, the logic of containment makes a fundamental “reset” in relations between Russia and the West, virtually impossible in the foreseeable future.

Second, it is necessary to realistically assess the readiness of the United States and NATO countries, which froze military cooperation with Russia in 2014, to reconsider this decision, without waiting for any serious shifts in relations between Russia and the West. Moreover, all the parties today consider the level of risks associated with dangerous military incidents acceptable 62. More serious arguments are required to substantiate the need to restore full-fledged communication along the military line without preconditions.

Third, given the fact that the modern intensification of military activity in the Arctic is mainly limited to the Euro-Arctic region adjacent to the North Atlantic, and that not only the Arctic states are involved in this activity, it is necessary to answer the question on the optimal composi- tion of participants in a dialogue or forum on security issues in the Euro-Arctic region, and not just in the “big” Arctic as a whole.

Why there is a need in a forum for dialogue on Arctic security issues?

The general logic of the arguments about the need to restore dialogue on military issues is understandable 63. The gap in regular communications between Russia and other Arctic countries that arose after 2014 is being filled by the parties with rhetoric and demonstration of their military capabilities. Thus, they send signals to each other, denoting “red lines” that should not be crossed. But these signals can be misinterpreted, which can lead not to de-escalation, but, on the contrary, to a further exacerbation of the military-political situation, especially in a situation when all parties are calculating the worst scenarios, based on the assessment not of intentions, but opportunities for each other. Therefore, it is necessary to agree on certain rules or “code” of conduct.

However, it would be wrong to assume that contacts between the military structures of Russia and the West are completely absent today. Since 2018, the Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces has met with the Supreme Commander of the NATO Joint Armed Forces in Europe. The participants of these meetings exchange assessments of the European security situation, inform each other about the planned major operational training events, and discuss measures to prevent incidents on the Russia-NATO contact line 64.

Understanding the risks of misinterpreting military activities, the General Staff of Norway maintains communication channels with the command of the Northern Fleet and the Russian General Staff [13, Wither J.K.]. Despite the sanctions, the annual Russian-Norwegian joint search and rescue exercise in the Barents Sea continues 65. In accordance with the Vienna OSCE Document on Confidence and Security-Building Measures, Norway notifies in advance of upcoming major exercises on its territory and provides relevant information about them. Although naval activities are not covered by the provisions of the Vienna Document, the United States informed Russia about the upcoming naval exercises in the Barents Sea in 2020 66.

In the context of a return to the policy of mutual deterrence, the 1972 Agreement between Moscow and Washington on the prevention of incidents on the high seas and in the airspace became relevant again. The practice of applying this agreement is being improved taking into account modern realities. Russia has a similar agreement with Great Britain and a number of NATO countries 67. Both the Northern Fleet and the US Second Fleet follow the requirements of the agreement in the areas of contact.

These and other similar examples support the arguments of those who believe that the existing agreed measures are sufficient to prevent the uncontrolled escalation of potentially dangerous military incidents. However, the current intensification of military activity in the Euro-Arctic region raises a number of questions to which the existing measures do not provide an answer.

It is clear that any military activity in the Barents Sea region, even in relative proximity to the basing and patrolling areas of Russian strategic missile carriers, would be perceived by the Russian side as potentially hostile. The Northern Fleet has an echeloned defense system for Russia's naval strategic nuclear forces, known in the West as “Bastion”. In the West, primarily in Norway, there are concerns that the range of Russian anti-aircraft, anti-submarine and anti-ship defense systems in the Barents Sea allows Russia to “close” vast sea areas far beyond Russian territory for any activity — up to the reconstructed NATO anti-submarine GIUK gap [1, Spohr K., Hamilton D.S., p. 200–202].

Measures to prevent the escalation of dangerous military incidents and occasional communication between senior military officials are clearly not enough to remove or at least minimize the corresponding concerns on both sides. This requires a regular, desirably institutionalized dialogue at various levels, to discuss assessments of the military-political situation in the region, mutual concerns and the motives of their activities in the region, including conducting exercises, snap checks of the combat readiness of forces and means or relocation of large combat teams.

The dialogue could lead to formal or informal arrangements that would help to ensure that the new military-political situation in the Euro-Arctic region remains stable, predictable and controlled. This could include agreeing on a standardised procedure for mutual emergency notification of military movement in the Arctic during natural disasters or other emergencies to avoid misinterpretations and miscalculations 68.

Who should be involved in such a dialogue?

The Russian Federation favours re-establishing dialogue forums on military-political issues among the eight member states of the Arctic Council. Since military security issues were excluded from the Arctic Council mandate, Moscow proposes to resume regular meetings of the chiefs of general staff of the Arctic countries’ armed forces, which were held on an annual basis until 2014. If this cannot be done immediately, it is proposed to start with military expert meetings of the eight countries' general staffs. At the same time, Moscow is sceptical about the possible expansion of the number of participants in such a dialogue 69.

Of course, discussion of military security issues in the Arctic should not exclude any of the Arctic states, and the independent format of such discussions within the Arctic G8 is important. But is it possible to ignore the fact that military activities in the Euro-Arctic region today are carried out not only by the Arctic states, but also by individual non-Arctic NATO member states, as well as the alliance as an organisation, and they would not be bound by any agreements that can be achieved without their participation?

For obvious reasons, Russia is not satisfied with the option of NATO’s involvement in a dialogue on security issues, not only in the entire “big” Arctic, but also in the narrower Euro-Arctic region. Moscow has long and consistently advocated that the alliance should not be endowed with any formal role in the Arctic. And the current paralysis of dialogue within the Russia-NATO Council does not allow counting on productive communication on significant security issues in the region.

For these reasons, the decision to resume discussions on security issues in the Euro-Arctic region along with the Arctic G8 in an expanded format that would include individual NATO countries that are somehow engaged or capable of engaging in military activities in the region seems to be optimal.

This format existed until 2014. This is a round table of the Arctic security forces. Its meetings have been held since 2011 with the participation of Navy representatives not only from the Arctic countries, but also from Great Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and France — non-regional states that regularly participate in military exercises in the Arctic and, therefore, whose involvement in the discussion of issues security is quite justified [5, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 69–70]. Since 2014, Russian representatives have no longer been invited to round table meetings. Regardless of whether the resumption of Russia’s participation in its meetings is possible, this composition of participants roughly determines the circle of states with which it is advisable to discuss security issues in the Euro-Arctic region.

What could be the format of the dialogue?

The restoration or establishment of any new official formats (meetings of chiefs of general staff or just their representatives, round table meetings, etc.) to discuss security issues in the Arctic as a whole or in a narrower Euro-Arctic region seems unlikely in the foreseeable future. A decision of the leadership of individual Arctic countries is not enough, but a consensus of the NATO and EU member states will be needed to review the sanctions they adopted in the context of the Ukrainian crisis in 2014. But even in some Arctic countries, such a decision would not be easy to make.

In particular, the US Congress annually extends the 2014 ban on any bilateral military cooperation with Russia 70. Similar bans exist in other NATO countries. As a first step, some experts have suggested establishing an informal forum to discuss military security issues in the Arctic, which would bring together military representatives from all Arctic countries (possibly adding some European non-Arctic states), but not in their official status, but as experts, thus circumventing Western formal restrictions on military contacts 71.

If the participation of representatives of the military departments of Western countries in such a format nevertheless turns out to be impossible, the gap in dialogue could initially be partially filled by regular roundtable meetings or conferences on Arctic security as part of the "second track", with participation of competent experts from the relevant states, including retired officers [14, Zagorskiy A.V., p. 16].

Conclusion

In the context of Russia and Western countries returning to a policy of mutual military restraint, the military-political situation in the Arctic is also changing. But the changes are uneven across the region. While in the most part of the region military activity is still hampered by severe climatic conditions, it has appreciably intensified in the Euro-Arctic region adjacent to the North Atlantic in the recent years. Today, the waters of the Barents and Norwegian Seas have again, as in the years of the Cold War, become an integral part of the military activities carried out by both Russia and NATO countries in Europe and the North Atlantic. This occurs in the context of a significant, if not total, cessation of military dialogue between Russia and Western countries, which contributes to a further deterioration of the military-political situation in the Euro-Arctic region.

Russia is particularly concerned with renewed military activities of the US and some NATO countries in the Barents Sea region, where a significant part of Russian maritime strategic nuclear forces is based on the Kola Peninsula. Increasing concerns on the part of the alliance countries are the capabilities of the Northern Fleet to “close” vast spaces in the Barents and Norwegian Seas to military activities by Western countries far beyond Russian territory. It is also believed that the regular voyages to the North Atlantic by Russian multipurpose nuclear submarines could threaten the alliance’s maritime communications.

The remaining tools to prevent the escalation of possible dangerous military incidents at sea and in the air are not enough to remove or minimise these concerns of both sides. This circumstance emphasizes the urgent need to restore a full-fledged, regular and institutionalized dialogue along the military line between Russia and the rest of the countries of the region, with the possible involvement of a number of non-Arctic states carrying out military activities in the Arctic. Such measures could include the resumption of the annual meetings of the chiefs of general staff of the Arctic countries, which were held until 2014, or, as a first step, military experts of the general staffs, as well as the resumption of participation of Russian representatives in the round table meetings on Arctic security.

However, these options are difficult to implement in the context of the continuation of the Western sanctions policy. The post-2014 freezing in military communications with Russia prevents Russian officials from inviting them to dialogue on military security in the Arctic. In this regard, much will depend both on the political will of the NATO member states and on progress in resolving current conflicts that have become a pretext for imposing sanctions against Russia, primarily the Ukrainian conflict.

Since Western countries at this stage are not ready to resume the dialogue, it could initially take the form of an informal forum, with civilian and military participants acting in a personal capacity, or regular roundtable meetings or conferences on Arctic security issues under “second track”.

Acknowledgments and funding

The article was published within the framework of the project “Post-Crisis World Order: Challenges and Technologies, Competition and Cooperation” under a grant from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation to conduct large research projects in priority areas of scientific and technological development (Agreement No. 075-15-2020-783).

Список литературы Military-Political Situation in the Arctic: Hotspots of Tension and Ways of De-Escalation

- Spohr K., Hamilton D.S. The Arctic and World Order. Washington, Foreign Policy Institute. In: Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs. Johns Hopkins University SAIS, 2020, 426 p.

- Humrich Ch. Kooperation trotz Großmachtkonkurrenz: Die Folgen des Klimawandels in der Arktis. Osteuropa, 2020, vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 99–115. DOI: 10.35998/oe-2020-0032

- Huebert R. The New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment (NASTE). Canadian Global Affairs Insti-tute, 2019, pp. 75–93.

- Anthony I., Klimenko E., Su F. A Strategic Triangle in the Arctic? Implications of China–Russia–United States Power Dynamics for Regional Security. Stockholm, SIPRI, 2021, 28 p.

- Zagorskiy A.V. Bezopasnost' v Arktike [Security in the Arctic]. Moscow, IMEMO RAN Publ., 2019, 114 p. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.20542/978-5-9535-0570-3

- Soldatenko S.A., Alekseev T.V., Ivanov N.E. et al. Ob otsenke klimaticheskikh riskov i uyazvimosti prirodnykh i khozyaystvennykh sistem v morskoy Arkticheskoy zone RF [On the Assessment of Climatic Risks and Vulnerability of Natural and Economic Systems in the Marine Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation]. Problemy Arktiki i Antarktiki [Arctic and Antarctic Research], 2018, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 55–70. DOI: 10.30758/055-2648-2018-64-1-55-70

- Konovalov A.M. Transportnaya infrastruktura rossiyskoy Arktiki: problemy i puti ikh resheniya [Transport Infrastructure of the Russian Arctic: Problems and Solutions]. Moscow, IMEMO RAN Publ., 2011, pp. 120–141. (In Russ.)

- Christensen K.D. The Arctic. The Physical Environment. Defence R&D Canada, Centre for Operational Research and Analysis (CORA), 2010, 128 p.

- Balasevicius T. Towards a Canadian Forces Arctic Operating Concept. Canadian Military Journal, 2011, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 21–31.

- Forget P. Bridging the Gap: The Limitations of Pre-AOPS Operations in Arctic Waters. Canadian Na-val Review, 2012, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 6–20.

- Todorov A.A., Lyzhin D.N. The UK’s Interests in the Arctic. Arktika i Sever [Arctic and North], 2019, no. 36, pp. 84–95. DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2019.35.84

- Wezeman S.T. Military Capabilities in the Arctic: A New Cold War in the High North? Stockholm, SIPRI, 2016, 24 p.

- Wither J.K. Svalbard, NATO’s Arctic ‘Achilles’ Heel’. The RUSI Journal, 2018, no. 163(5), pp. 28–37. DOI: 10.1080/03071847.2018.1552453

- Zagorskiy A.V. Rossiya i SShA v Arktike [Russia and the United States in the Arctic]. Moscow, NP RIAC Publ., 2016, 24 p. (In Russ.)