Miniature anthropomorphic sculptures from Ust-Voikary: chronology, context, semantics

Автор: Garkusha V.N., Novikov A.V., Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

We publish a sample of anthropomorphic sculptures unearthed in 2012–2016 at the Ust-Voikary fortified settlement in the circumpolar zone of Western Siberia. This is one of the permafrost sites, where artifacts made of organic materials are well preserved. The vast majority of the sculptures are made of wood, two of sheet metal, and one from a limonite concretion. Four main categories are identified: busts, heads, relatively full anthropomorphic figurines, and masks on sticks. Most of the sculptures follow the tradition of Ob-Ugric art, while a few can be attributed to Samoyedic art. Some figurines have additional elements such as rows of notches and diamond-shaped signs. According to ethnographic data, these signs endowed the sculptures with a sacral status. The finds have a clear archaeological, architectural, and dendrochronological context. Most were discovered in cultural layers dating to the early 1500s to early and mid-1700s. The artistic style is analyzed, and parallels are cited. The sculptures are compared with 18th to early 20th century ethnographic data. The connection of most figurines with dwellings, their small size and style show that they all belong to the ritual wooden anthropomorphic sculpture and were attributes of domestic sanctuaries. They fall into two main categories: family patron spirits and ittarma—temporary abodes of souls of the dead.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146986

IDR: 145146986 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.2.108-118

Текст научной статьи Miniature anthropomorphic sculptures from Ust-Voikary: chronology, context, semantics

Archaeological sites with the permafrost cultural layer in northwestern Siberia have exceptional information potential for studying the culture of the indigenous population of the region. Such sites are the main source of information concerning the history of wooden sculpture by the local population. These are Nadym and Polui promontory forts, and the Ust-Voikary fortified settlement, which are dated to the second third of the 2nd millennium AD. Currently, a total of more than 150 miniature wooden anthropomorphic sculptures originating from these sites has been recorded. About half of these have been recovered from the Ust-Voikary fortified settlement in the southwestern part of the YaNAO; the site was excavated in 2003–2008 and 2012–2016 (Garkusha, 2020). The data from the dendrochronological analysis have shown that this settlement was populated in the range from the turn of the 13th–14th centuries to the 19th century (Gurskaya, 2008). The population of the fort has been tentatively identified as Ugric-Samoyedic with a certain admixture of the Komi-Zyryan component (Martynova, 1998: 82; Perevalova, 2004: 231–233). About 30 items discovered at the site in 2003–2008 were published in the electronic catalog of the Shemanovsky Museum-Exhibition Complex (Salekhard). This article introduces 48 anthropomorphic figurines found during the excavations in 2012–2016. Almost all the items were made of wood; two pieces are from sheet metal, one figurine is

fashioned on a disc-shaped limonite concretion*. Thus, the relatively small excavation area at Ust-Voikary fortified settlement revealed ca 80 anthropomorphic images. An explanation of this concentration can be found in the famous message of V.F. Zuev (1947: 41) about his trip to the Obdor Territory (in 1771): “Everyone in the chum, including women and girls, has his or her own idol, sometimes two or three, whom they amuse every day according to their custom”.

Typology of anthropomorphic figurines

The first typological classification of the anthropomorphic images was made for the materials from the Nadym and Polui promontory forts (Kardash, 2009: 188–189; 2013: 200–201). Three types have been identified: I – masks on sticks, II –sculpture, III – monumental sculpture. Type II has been further subdivided into three sub-types: 1) busts, 2) sculpture proper; and 3) multi-faced images. The proposed typology does not seem correct concerning the terms. The term “sculpture” refers to the common technique of producing the images, rather than to their morphology. S.V. Ivanov referred to the works of art historians and wrote: “Sculpture (from the Latin sculpere ‘carve’, ‘cut’)… means ‘carving’, ‘cutting out’, ‘hewing’, i.e. a process in which a craftsman, in one way or another, using one tool or another, removes excess parts of the piece of wood or stone he is processing, gradually giving the remaining solid mass the necessary shape” (1970: 5). Thus, all the analyzed images belong to one category— anthropomorphic sculpture. In this regard, we find it appropriate to propose a different typology.

We subdivided the miniature anthropomorphic wooden sculptures from Ust-Voikary into the following categories: 1) busts; 2) heads; 3) relatively full anthropomorphic figures; 4) masks on sticks; 5) dubious (bearing signs of anthropomorphism). Further typology is based on the presence or absence of additional details.

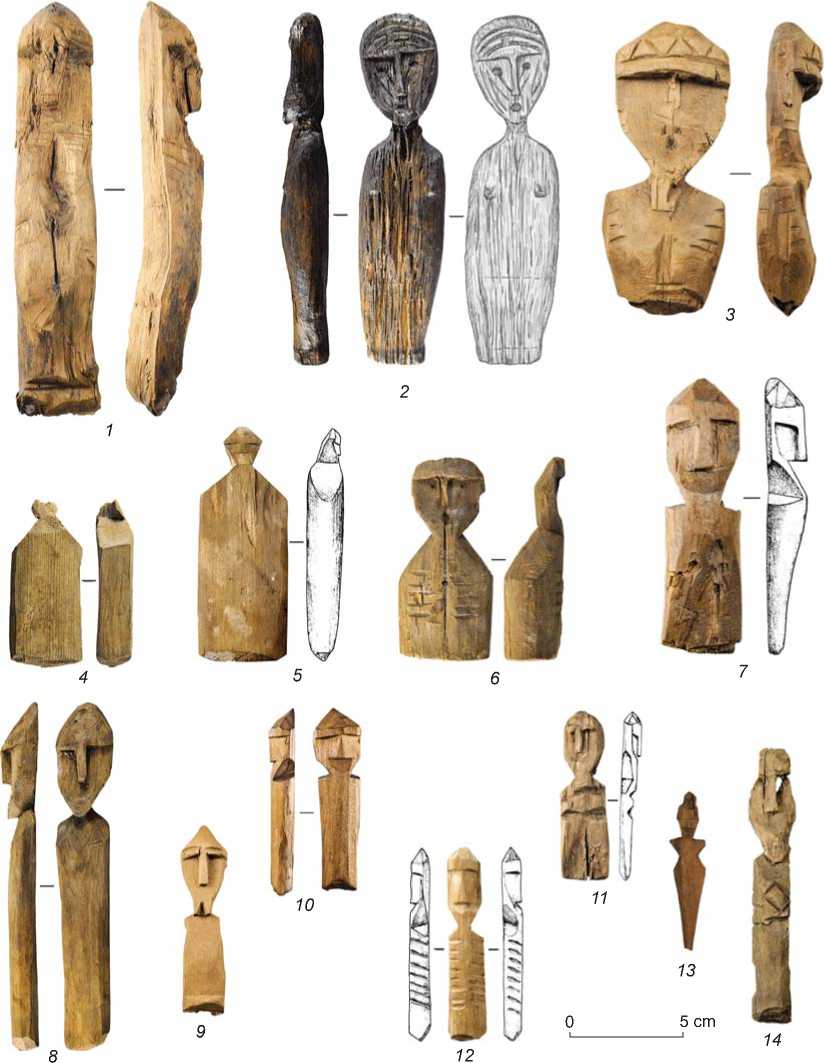

Busts (Fig. 1; 2, 1–4, 6, 10–13). This is the largest category. Busts include sculptural three-dimensional images of the upper part of a human figure—chest-high or waist-high images. Anthropomorphic features are imparted by modeling the head, neck, and shoulder girdle, often with the addition of relief individual facial features, mainly the lines of eyebrows and nose. Sometimes, eyes and mouth are also shown. In some figures, only eyes are depicted with pinpoint punctures (Fig. 2, 3). One of the bust figurines shows the arms rendered by triangular protrusions (see Fig. 1, 13); in the other figurine, the arms are only outlined (see Fig. 1, 9). Sometimes, the body bears ornamentation in the form of various notches and geometric figures. The height of the figurines ranges from 7 to 15 cm.

According to the design of the upper part of the head, the busts are subdivided into two types: with a pointed head (see Fig. 1, 1 , 3 , 5 , 7–14 ; 2, 1 , 11 , 12 ) and “roundheaded” (see Fig. 1, 2 , 6 ; 2, 2–4 , 6 ). The head of one of the busts was partially destroyed; hence, its shape is indeterminable (see Fig. 1, 4 ). One of the figurines is noteworthy: its head is significantly large, while the body is shown only by a fragment of the shoulder girdle (see Fig. 2, 1 ).

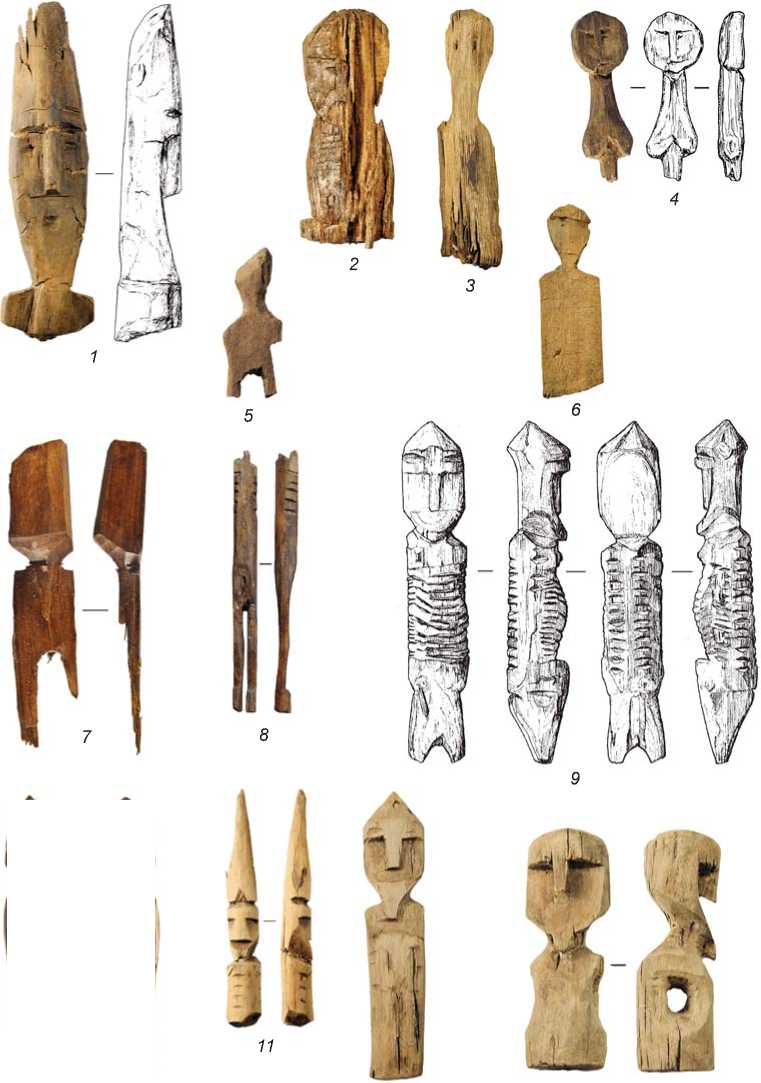

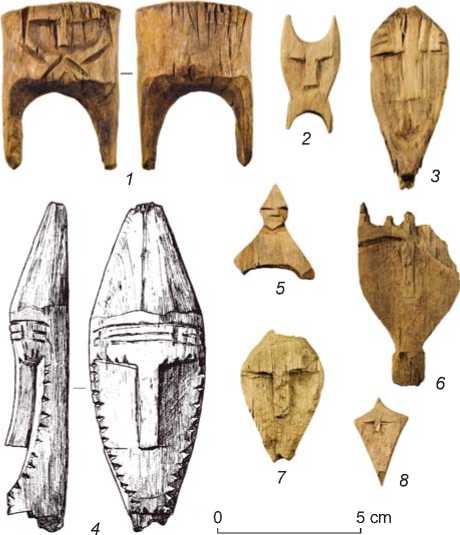

Heads (Fig. 3). These are the intentionally produced images of separate heads with detailed facial features. Three images show modeled necks (Fig. 3, 3 , 4 , 6 ). The images are 3–12 cm high, 4–7 cm on average. By the design of the upper part of head, four types have been distinguished: 1) pointed head (Fig. 3, 3–5 , 7 , 8 ), in two cases, the lower part of head is also pointed (Fig. 3, 7 , 8 ); 2) heads with two “spikes” (Fig. 3, 2 ), an additional design feature is two protrusions in the lower part of the head, which are compositionally symmetrical with the “spikes”; 3) heads with a number of protrusions (“crown”) on top (Fig. 3, 6 ); 4) with a flat top (Fig. 3, 1 ), an additional design feature is two elongated “spikes” in the lower part.

Relatively full anthropomorphic figurines (see Fig. 2, 5 , 7–9 ). These images show not only modeled heads, necks, shoulder girdles (sometimes also arms, see Fig. 2, 5 ), but also legs. By the design of the upper part of the head, only one type can be distinguished—with a pointed head (see Fig. 2, 9 ). Two figurines show conventionally modeled heads, with their facial features not visible. There is a figurine with a missing head. The body might show horizontal notches. The height of the figurines ranges from 6.5 to 14.5 cm.

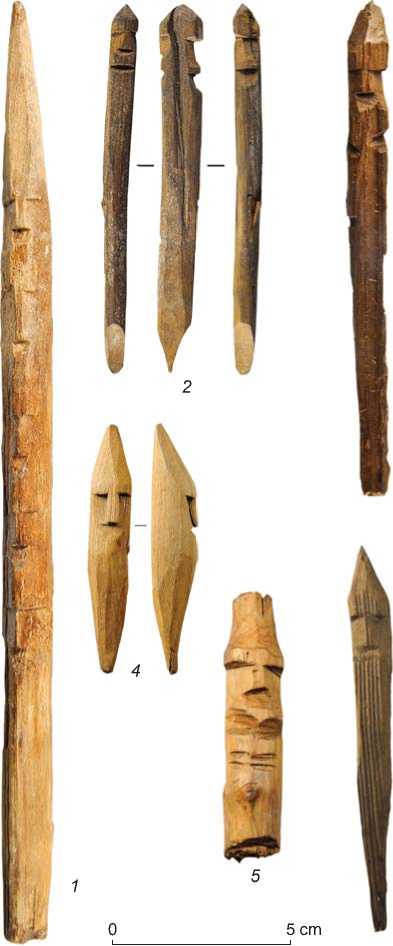

Masks on sticks (after (Kardash, 2009: 188; 2013: 200)) (Fig. 4). The iconography is distinguished by the absence of a body (there are no features of head, neck, shoulder girdle, or legs). The masks are carved on planed sticks. In four cases, the sticks are deliberately pointed or straight in the lower part. All images in this category belong to one type—that with a pointed head. The only relief facial features are brow-lines and nose. Some sticks bear horizontal notches below the masks. The items exhibit great variability in size: from 3 to 27 cm. The height of the majority of the products is ca 10–11 cm. By the number of depicted masks, two types have been distinguished: one-faced (Fig. 4, 3–6 ) and multi-faced (Fig. 4, 1 , 2 ). In one case, five masks are located vertically on one side of the stick; in the other, two masks are located symmetrically on the opposite sides of the stick.

Dubious (bearing anthropomorphic features) (Fig. 5, 1–4 ). This category includes four items without a morphologically convincing set of anthropomorphic

Fig. 1. Busts.

1 , 11 , 12 – layer dated to the second half of the 16th century; 2 , 3 , 13 , 14 – layer from the first half of the 16th century; 4 , 9 – layer from the 17th century; 5 , 6 – layer from the mid-17th century; 7 – layer from the early 17th century; 8 , 10 – layer from the first third of the 16th century.

features. Nevertheless, these images display certain signs of modeling the head (sometimes, arrow-shaped) and the shoulder girdle. The morphologically close images are apparently those of souls of the dead from the 19th-century burials in the Lower Ob region (Murashko, Krenke, 2001: Fig. 150, 1 , 2 ).

Chronology and location of anthropomorphic images

The dendrochronological analysis has shown that the dwellings containing the figurines were built in the range from the early 16th to the mid-18th century (Garkusha,

5 cm

Fig. 2. Busts ( 1–4 , 6 , 10–13 ) and relatively full anthropomorphic figurines ( 5 , 7–9 ).

1 , 9 , 11 – layer from the first half of the 17th century; 2 – layer from the second half of the 17th century; 3 , 5 , 12 , 13 – layer from the first half of the 16th century XVI; 4 , 8 – layer from the first third of the 16th century; 6 , 10 – layer from the late 15th to early 16th century; 7 – layer from the second half of the 16th century.

2022). The dwellings were constructed in tiers of various heights. The dates of wood samples from inter-dwelling space generally correspond to the chronology of a specific building horizon containing several dwellings. The derived dates establish a chronological link to the places of origin of the figurines in particular sections of the interdwelling cultural layer. These chronological estimations are not applicable to the figurines discovered on the slopes

Fig. 3. Heads.

1 – layer from the 16th century; 2 – layer from the first half to mid-17th century; 3 , 5 , 7 , 8 – layer from the first half of the 16th century;

4 – layer from the second half of the 17th century; 6 – layer from the 16th–17th century.

of the hill containing the site, because their position is obviously random (in the analyzed sample, only one figurine comes from the slopes).

Any direct extrapolations of the dates of the buildings to the context of discovery of the figurines are incorrect owing to the arbitrary accumulation of the filling of the destroyed dwellings. The leveling of the area for new construction over the destroyed buildings was carried out by piling up a layer of mixed small woodworking residues (chips, etc.), which were the main structural element of the cultural deposits. Obviously, the fill material originated from the areas outside the dwellings. In such a situation, the inclusion of items in the filling may be accidental.

Chronological references of areas of infill containing artifacts are reasonably acceptable when the item is deposited between the dated tiers of various structural elements (for example, planking) or near the level of a wooden floor. If the floor of the dwelling is a section of cultural layer not covered with wood, then the attribution of the artifact to the corresponding building is conditional. An additional argument for establishing a reliable upper

Fig. 4. Masks on sticks.

1 – layer from the second half of the 16th century; 2 – layer from the 17th century; 3 , 5 – layer from the 16th century; 4 – layer from the middle to second half of the 17th century; 6 – layer from the 16th–17th century.

chronological limit of the layer containing the item is the date of the overlying structure. The overwhelming majority of the figurines under study were recovered from a clear archaeological and architectural context, with a chronological reference to the sections of the containing layer. More than a third (38 %) of the artifacts were recovered from inter-dwelling space; the rest were found in buildings classified as residential owing to the presence of a fireplace. The number of figurines found in the dwellings, regardless of their size, is small: usually one or two (with the exception of building 7/2). Some buildings did not yield any figurines.

The relative architectural integrity of the interior layouts of the dwellings makes it possible to evaluate the spatial distribution of the items in the room. First, it

Fig. 5. Wooden figurines of the “dubious” category ( 1–4 ), and items made from other materials ( 5–7 ).

1 – layer from the 16th century; 2 , 3 , 7 – layer from the first half of the 16th century; 4 – layer from the second half of the 16th century;

5 – layer from the first half of the 18th century; 6 – layer from the 17th century.

concerns large houses, where the main structural elements of spatial organization are clearly visible: the area in front of the entrance, bunks along the perimeter of the dwelling or along its side walls, the central part of the room, the area adjacent to the hearth, etc. In small residential buildings, for example, the availability of bunks or wooden floors is not reliably identified.

In a number of cases, the lack of adequate stratigraphic markers between adjacent tiers of buildings prevents reliable attribution of items to a certain dwelling. This situation is due to the fact that tiers of new buildings of the same type arose directly on the ruins of the previous constructions, with a slight variation in the boundaries. In this regard, the “complex of buildings” category was introduced, which defined a combination of artifacts from different stratigraphic levels of a conventionally identified macro-structure. The tiers with the most clearly identifiable remains of structural elements of buildings have been regarded as upper and lower boundaries of the complex. The relevant chronology was established based on the results of dendrochronological analysis.

The complex of buildings 7/1–7/2*, existing from the early 16th to the beginning of the second third of the 18th century, revealed the greatest number of sculptures (21 spec.). The tiers of the complex are formed by frame-and-post dwellings identical in their design and interior space organization. Similar buildings have been recorded, in particular, during excavations of Fort Nadym (Kardash, 2009: 56–57). The main features of the buildings are as follows: a fenced central heated room; an open hearth in the center; a “gallery”—a passage formed by the external walls of the dwelling and the fencing of the central room. We consider the long use of the complex of buildings 7/1–7/2 as a possible explanation of the presence of the largest number of sculptures here. Among these, 18 items are associated with the early building 7/2 used mainly in the 16th century.

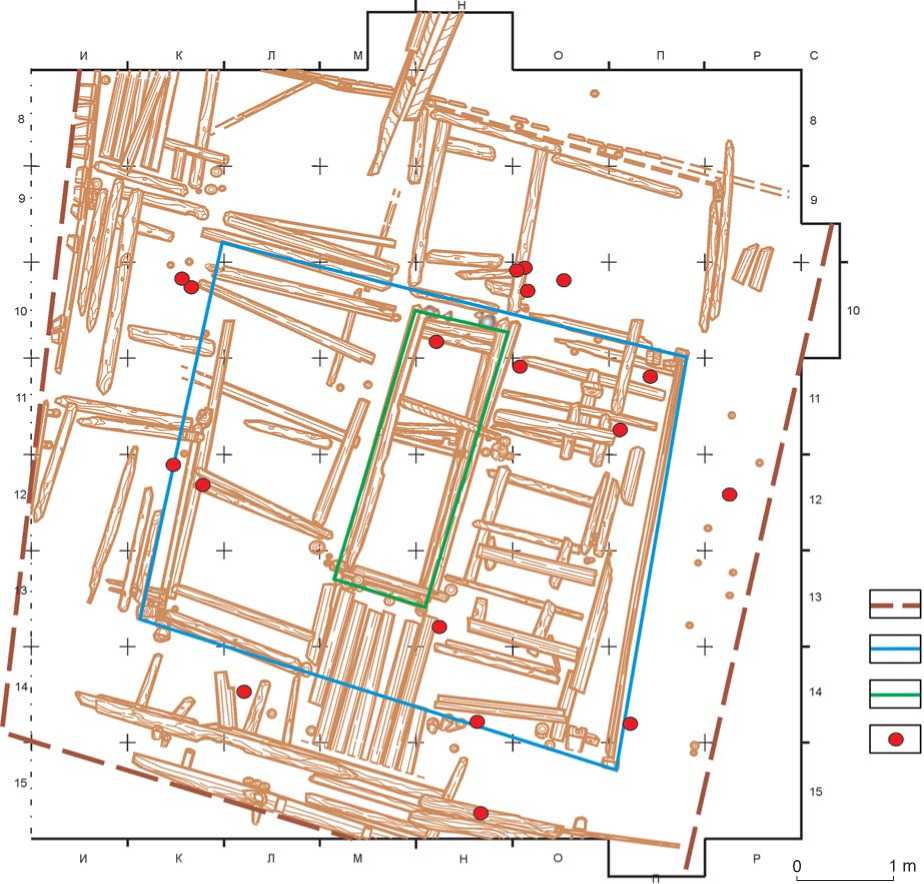

Anthropomorphic figurines occur all over the area of dwelling 7/2 (Fig. 6). At the same time, some of them were associated with the areas traditionally connected with ritual ceremonies**, or were included

into collection of items intended for the performance of various rituals. One of the sacred zones is the hearth—the object of special treatment and ritual actions in the Ob Ugrians. The hearth has the form of a wooden rectangular frame with a marked fire pit and a small “utility” compartment. In the latter, along with household utensils, items for ritual purposes were found: wooden zoo- and ichthyomorphic images, and figurines for playing tos-cher-voi . There was also an anthropomorphic sculpture here (see Fig. 1, 14 ).

Another cluster of items was found in the “gallery” area located opposite the entrance to the dwelling. This included a birch-bark mask, a large wooden model of a broadsword, votive arrowheads, the parietal part of a deer skull, and two anthropomorphic images (see Fig. 2, 12 , 13 ). Two more figurines were found in the immediate vicinity of the cluster (see Fig. 2, 3 ; 5, 7 ), which allows us to combine them into a single unit. One of the items is a fragment of a silhouette made of iron. This set could initially have been stored in some kind of container such as a birch-bark box or canvas bag (later, Russian chests were used for this purpose) and pertain to family attributes associated with the veneration of heroic ancestors and the cult of the bear (see, e.g., (Kannisto, 1958: 314)).

with adjacent upper bunks or a corner shelf for arranging the cult attributes of the family (Gemuev, 1990: 23–28).

1 m а b c d

Fig. 6. Scheme of arrangement of the sculptures in dwelling 7/2 (the 16th century). a – external boundary of the dwelling; b – boundary of the central room; c – hearth area; d – locations of figurines.

The indicated part of the “gallery” also revealed other ritual items or those close to them in purpose. Sculptures of animals, votive weapons, and many figurines for the tos-cher-voi game were found here in clusters of several dozen items.

In the entrance area, between the tiers of floorboards, a stick bearing five carved masks was found (see Fig. 4, 1 ). Other anthropomorphic images belonging to different categories were also found in the area of building 7/2 (see Fig. 1, 1 , 3 , 7 , 11 , 12 ; 2, 5 , 9 ; 3, 3 , 5 , 7 , 8 ; 4, 1 ; 5, 2 ).

The discoveries of figurines in situ, in a specially designated place near the wall opposite the entrance, were reported from the contemporaneous dwellings in other “Ostyak” towns. In particular, the figurine from building 3 of the trading quarter of the Polui promontory fort* was found in a small rectangular pit planked with the boards used for bunk construction (Kardash, 2013: 201).

Items associated with building 7/1, which dates back to the second half of the 17th century (see Fig. 1, 5; 3, 2; 4, 4), were found in various parts of the “gallery” and the main room. Only one anthropomorphic image—a figurine made from a concretion (see Fig. 5, 5)—was found in the log building 7 (built at the beginning of the second third of the 18th century), which was the latest cons truction of the complex under consideration. The figurine lay between the boards of the bunks arranged along the wall opposite the entrance.

Figurines were also found in other specific areas of dwellings: a wooden structure resembling a long rectangular “trough” of boards leading through a hole in the wall opposite the entrance onto the hillside. It was discovered during the clearing of building 8 in 2004– 2005; the structure was interpreted by N.V. Fedorova as a drain (2006: 15).

Parallels

The collection under consideration contains specimens very similar to one another. This is a morphologically close pair of wooden figurines with elongated shoulder girdles (see Fig. 1, 4 , 5 ). One more figurine, with a larger and more thoroughly prepared head, is also similar to them (see Fig. 1, 6 ). These items were found in a small area in the layer attributed to the 17th century. Two head images show similar appearance, in which the edges of facial parts are rendered with notches. One artifact (see Fig. 3, 4 ) was discovered in the area adjacent to building 7/1; the other was recorded among the materials from the first stage of field research at the site (Istoriya Yamala, 2010: 216).

Certain parallels in the specific design of individual elements of the images are found among the materials from other old towns. In particular, the figurines from Ust-Voikary (see Fig. 1, 9 ) and Nadym (Kardash, 2009: 273, fig. 3.77, 7 ) show a similar design of the chin: it is marked by a protrusion divided into two parts by a deep vertical notch. The relatively full figurine executed in the extremely stylized way also finds its parallels (see Fig. 2, 7 ). The images of souls of the dead from the Lower Ob region cemeteries of the 19th century show similar forms (legs and head are marked, but facial features are not shown) (Murashko, Krenke, 2001: Fig. 149, 150, 3 , 4).

An item from the “head” category, with an unusual shape, has been classified as a fragment of some kind of product (see Fig. 3, 5 ). Its configuration resembles the top of handles decorated with a mask from the Polui promontory fort (Kardash, 2013: 244, fig. 3.26, 1, 4 ). However, the Polui items are made of horn and are more robust. Perhaps the Ust-Voikary artifact is an imitation of such a handle.

In 25 % of the figurines, the body is decorated with vertical rows (usually two) of short notches placed close to the sides. There is a popular hypothesis that the rows of notches symbolize human ribs (Ivanov, 1970: 25, 54). This interpretation is possible when the rows are arranged in that way, but their different position makes it doubtful. For example, one of the figurines shows the notches made in the “belly” area (see Fig. 1, 3 ); the other bears the rows of notches tightly covering all sides of the torso (see Fig. 2, 9 ).

In a number of images, the notch ornament is complemented by a diamond-shaped sign (in one case, with the inserted second diamond) located in the middle part of the body. It occurs on both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines. This symbol has been recorded on oriental silver bowls with images of people and animals at least since the medieval period (Spitsyn, 1906: Fig. 7, 9, 22, 25). According to the ethnographic data on the Ob-Ugric populations, the diamond on anthropomorphic images provides a certain semantic status (a sign of sacredness, a symbol of vitality) (Ivanov, 1970: 25, 41; Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 19; Baulo, 2016: 68).

Only one figurine was identified as a depiction of woman (see Fig. 1, 2 ). Its facial part is rendered with carved lines along the face outline. Perhaps this motif conveys make-up or a tattoo. The figurine was discovered in one of the small buildings of the early 16th century. No parallels are known to this artifact.

The mask with a “crown” (see Fig. 3, 6 ) has analogs in medieval bronzes of the Middle and Lower Ob region (Baulo, 2011: 72). As a rule, “crowns” have three protrusions topped with zoo- and anthropomorphic images. In our specimen, the protrusions are damaged, but judging by their density, there were five or six of them. The item was discovered in the inter-dwelling space, in the layer from the 16th–17th centuries. This anthropomorphic figurine is semantically close to the image with the front part of its flattened headdress rendered with three (the fourth is marked) cut out triangles (see Fig. 1, 3 ). On the one hand, the motif can be interpreted as a way of conveying a three-rayed “crown”, on the other, it can be considered as a grid motif characteristic of bronze tiaras found at the Kulai and Parabel cult places. N.V. Polosmak and E.V. Shumakova (1991: 16–18) believe that such tiaras could have decorated wooden idols of the Ugrians.

A peculiar miniature sculptural image of a head was found in the central room of building 7/1, in the layer from the first half of the 17th century (see Fig. 3, 2 ). The upper and lower flat ends of the artifact bear pairs of pointed protrusions at their sides. Among the images of representatives of the Ugric pantheon, found in sanctuaries (mainly Mansi), both anthropomorphic figures, with their heads crowned with horn-like protrusions, and anthropozoomorphic ones have been occasionally found. In a similar way are rendered the ears of an eagle owl in the image of Yipyg-oyka (‘old eagle owl’), the patron saint of one of the Mansi villages (Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 10, 11, fig. 4). Cone-shaped protrusions were noted at the anthropozoomorphic figurine found at the sacred site of Shchakhel-Torum (Gemuev, 1990: 136, fig. 121, p. 137). Similarly to the above parallels, our artifact shows one of the ways of depicting an imaginary creature combining the features of a human and an animal (probably, an ornithomorph).

Planed long sticks with masks form a special category (see Fig. 4). There could be several masks located on different parts of the stick. Materials from other “Ostyak” towns contain figurines with two or three masks rendered in a traditional way, vertically (Kardash, 2009: Fig. 3.78, 3 ; 2013, fig. 3.51, 8 ). Among the Nenets, sculptures with seven masks were widespread (Ivanov, 1970: 73–77). More robust figurines with seven faces ( yalyani ) (about 1 m high) have also been reported from the northern Khanty (Ibid.: Fig. 18, 19). Complex compositions are also known among miniature sculptures. For example, a multi-headed figurine from Nadym is supplemented with images of several faces (Kardash, 2009: Fig. 3.77, 1 ). Notably, multi-faced compositions were also depicted on various ritual items: handles of Khanty shamanic tambourines were decorated with seven masks (Baulo, 2016: Fig. 123); the same is true for the Nenets tambourines (Ivanov, 1970: Fig. 85). Eight faces are represented on the ledge of a plank item from Nadym, interpreted as a shelf for cult items (Kardash, 2009: Fig. 3.75, 2 ).

Anthropomorphic figurines forged or cut from sheet metal (see Fig. 5, 6 , 7 ) are rarely found among the cult attributes of the Ob Ugrians. Noteworthy are iron figurines from an excavation at the memorable site of Sat-vikly (Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 107, fig. 98, 1–3 ). The height of a full figurine is ca 11 cm; the upper part of the other figurine is missing.

We do not know any parallels to the artifact made from a limonite nodule (see Fig. 5, 5 ). It is a disk with a diameter of 6.0–6.5 cm, with a protrusion on which the mask was carved. The artifact is ca 9 cm high*.

None of the figurines was associated with remains of textile items. At the same time, ethnographic data suggest that clothing is an important element in the design of wooden anthropomorphic figurines used for cultic purposes. Clothing exerts a significant influence on the interpretation of images in domestic sanctuaries of the Ob Ugrians and Samoyeds (Baulo, 2016: 190; Khomich, 1966: 202–204). However, solitary archaeological finds from the collections of “Ostyak” towns indicate that there were exceptions in this tradition, which could be the result of evolution of the perception of anthropomorphic images. The above-mentioned figurine from building 3, in the suburbs of the Polui promontory fort, was placed in an improvised box on a piece of board covered with fabric, and then with a layer of grass; actually, the figurine was naked (Kardash, 2013: 201).

The practice of using miniature anthropomorphic sculptures without specially prepared clothing, or fabric elements imitating it, possibly had a certain spread in ancient times. The absence of such elements can be assumed at least for the figurines whose surface is mostly covered with notches (possibly, for conveying outer fur clothing), and for multi-faced images. An argument in favor of the archaic nature of this approach to the design of sculptures (without prepared clothing) may be wooden and horn anthropomorphic figures from the Ust-Polui sanctuary (1st century BC to 1st century AD). The figurines are made in quite a realistic style; some show outerwear or its elements (a fur coat with a hood, a composite belt) (Fedorova, 2014: 65, fig. 2, 6–10).

Comparative analysis of the Ust-Voikary archaeological finds and ethnographic data from the 18th to early 20th century

Wooden anthropomorphic figurines from the 18th–20th centuries have been found in domestic sanctuaries of northern Khanty in the basins of several rivers: Kazym (Beloyarsky District of Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra), Polui (Priuralsky District of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO)) (Baulo, 2016: Fig. 130, 131, 191–196), Malaya Ob, Synya, and Voikar (Shuryshkarsky District of the YaNAO) (Ibid.: Fig. 59, 68, 70, 80, 184–190). Similar images associated with the cult of ancestors were found in the burials of the 19th century cemetery of Khalas-Pugor (Murashko, Krenke, 2001: 64).

The ritual sculptures are subdivided into two main categories: images of family patron spirits and ittarma — temporary abodes of souls of the dead. The former are a bust or a full figure with arms and legs (some have a diamond-shaped sign on the chest and notches indicating ribs). Their heads are round (for female characters) or pointed; eyes, nose and mouth are carved. A characteristic feature of Ugric iconography is the T-shaped line of the eyebrows and nose. Noteworthy is the depiction of a nose in some figurines, which is not straight, but noticeably widening downward (see Fig. 1, 10 , 12 ; 2, 11 ). S.V. Ivanov repeatedly mentioned this feature in his descriptions of the Nenets sculptures, without endowing it with exclusivity (1970: 77–79).

Since the veneration of patron spirits is based on the cult of heroic ancestors, male images are typically shown with a conical or flat helmet on their heads. Pointed heads of the sculptures are traditionally considered the signs of male images. However, this interpretation is not always unambiguous. In different groups of the Ob Ugrians, both northern and southern, female images with heads of conical shape are known (Ibid.: 26, fig. 11, p. 28, fig. 13, p. 31, fig. 17, 1 ; Kardash, 2009: Fig. 3.77, 7 ; 2013, fig. 3.51, 2 ). A significant part of the sculptural images from the fortified settlement of Ust-Voikary demonstrates the signs of Ugric family patron spirits (see Fig. 1, 1–3 , 6–12 , 14 ; 2, 1 , 2 , 9 , 11–13 ; 3, 1 , 4 ; 4, 1 , 2 , 5 ).

Sticks with masks are more often referred to as images of the Samoyedic affinity (see Fig. 4, 1–4 , 6 ). In the collection under consideration they make up a small proportion (ca 10 %). The largest number of such images was found in Fort Nadym (44 % of the finds from 1998–2005) (Kardash, 2009: 188). Notably, two figurines (see Fig. 4, 1 , 4 ) were uncovered from the filling of the complex of buildings 7/1–7/2.

Ittarma of northern Khanty in the 20th century was represented mostly by an anthropomorphic image cast of lead (Baulo, 2016: Fig. 276–278), or more rarely, made of wood (Ibid.: Fig. 279–280). Wooden ritual figurines are more typical of northern Mansi (Gemuev, 1990: 44–47, 53–55). Wooden cores for ittarma dominated until the early 20th century. For example, such figurines were discovered in 78 burials of the 19th century in the Lower Ob basin (Murashko, Krenke, 2001: 64–65). The ittarma of northern Mansi is carved from a flat wooden plate in the form of a bust with the head. These features make it possible to attribute six images from Ust-Voikary to this category (see Fig. 1, 4 , 5 ; 2, 3 , 6 , 7 ; 5, 2 ). Most of them were found in dwellings, which correlates well with the tradition of the Ob Ugrians to keep ittarma at home for a certain period of time (different for different local groups), after which, in most cases, the souls of the dead pass into the category of ancestral spirits protecting the family (Gemuev, 1990: 206–212).

Replacement of the wooden ittarma by the lead ones in the northwestern Siberia in the 20th century can be explained by the import of shot during the transition to firearms in hunting. In general, it can be noted that the sizes of idols associated with domestic sanctuaries became larger in the 18th–20th centuries than those found at the Ust-Voikary fortified settlement.

Conclusions

One of the results of the study of archaeological sites with the permafrost cultural layer was the accumulation of a corpus of sources on traditional sculptures of the peoples of northern regions of Western Siberia in the Middle Ages and Modern Age. The use of a dendrochronological approach in age estimations of constructions at Ust-Voikary fortified settlement made it possible to establish the lower boundary of existence of wooden anthropomorphic sculptures at the turn of the 15th–16th centuries. Analysis of the figurines under study has shown that as early as that time, Ugric populations in northwestern Siberia used a certain set of stylistic techniques known from sculptural images of an ethnographically modern period. Among them, noteworthy are vertical rows of notches on lateral sides of the body, and representation of a diamond-shaped sign.

The presence of such elements on the figurine endowed it with a sacral status.

The small size of the figurines (mostly not exceeding 15–16 cm) and their location in the dwellings’ interior areas indicate that the uncovered items are attributes of domestic sanctuaries. According to their purpose, they can be subdivided into two main groups: images of family patron spirits, and ittarma —temporary abodes of souls of the dead. Most sculptures follow the tradition of Ob-Ugric art; others can be attributed to Samoyedic art. The occurrence of sculptural images associated with both the Ugric and Samoyedic populations in close proximity to one another is typical of all the studied northern “Ostyak” towns.

Acknowledgements