Normative dissonance and anomie: a prospective microlevel model of adolescent suicide ideation

Автор: Lee J.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 7 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study constructs a unique prospective model of anomie and adolescent suicide ideation in order to test the two dominant sociological paradigms of suicide—(1) Durkheim’s theory of anomie and (2) suicide suggestion. This model looks at normative dissonance between the adolescent and the adolescent’s two social worlds, the family and the peer network, as sources of anomie. Normative dissonance is defined as conflicting norms and behaviors, such as smoking, academic aspirations, and religiosity. Baseline variables, including individual characteristics such as race, sex, and depression, as well as other variables that may be related to anomie, but not through the mechanism proposed in this paper are included in the full regression model. In 2001, suicide was the third leading causing of death among adolescents aged 10-19 years in the United States (CDC 2004(a)). In 2002, nearly 125,000 adolescents were taken to the hospital after an attempted suicide (CDC 2004(c)). Moreover, from 1970-93 the suicide rate among adolescents nearly doubled from 5.9 to 11.1 per 100,000 (US DHHS 2001) and has since decreased to 7.4 in 2002 (US DHHS 2004). Overall, there has been widespread concern regarding adolescent suicide, especially school-associated suicides. The CDC found that 25% of adoles-cents who committed suicide at school injured or killed someone else before committing suicide (CDC 2004(a)) and that 22% of students who carried out school shootings also killed themselves (CDC 2004(b)). Despite this increase in adolescent violence and suicides in schools, studies of adolescent suicide have largely adopted the theo-retical approaches developed for studying adult suicide. Within this broader area of suicide studies there are two dominant and competing sociological theories of suicide—Durkheim’s theory of social regulation and integration, established in Suicide (1897 [1997]), and suicide suggestion (Phillips 1974; Tarde 1903). This study seeks to resolve the debate between these two dominant sociological para-digms for understanding suicide within the specific context of adolescent suicide.

Normative dissonance, prospective Microlevel model, adolescent suicide ideation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010854

IDR: 16010854 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.7.30

Текст научной статьи Normative dissonance and anomie: a prospective microlevel model of adolescent suicide ideation

X RESEARCH x ARTICLE Normative dissonance and anomie: a prospective microlevel model of adolescent suicide ideation Jennifer Lee Professor Julian Clarence Levi Professor of Social Sciences, Department of Sociology, Columbia University Core Faculty: Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, Columbia Population Research Center, Director of the Asian American Initiative at Columbia University USA Email: , Doi Serial Keywords Normative dissonance, prospective Microlevel model, adolescent suicide ideation / Abstract / This study constructs a unique prospective model of anomie and adolescent suicide ideation in order to test the / two dominant sociological paradigms of suicide—(1) Durkheim’s theory of anomie and (2) suicide suggestion. This model looks at normative dissonance between the adolescent and the adolescent’s two social worlds, the family and

Lee J. (2025 Normative dissonance and anomie: a prospective microlevel model of adolescent suicide ideation. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context ofModern Problems, 8(7), 269-285; doi:10.56352/sei/8.7.30.

© 2025 The Author(s). Published by Science, Education and Innovations in the context of modern problems (SEI) by IMCRA - International Meetings and Journals Research Association (Azerbaijan). This is an open access article under the CC BY license .

Received: 04.3.2025 I Accepted: 06.04.2025 —I Published: 01.06.2025 (available online)

-

I. Durkheim’s theory of suicide

In his seminal work, Suicide , Durkheim (1897 [1997]) established a sociological theory of suicide based on the macrosocial effects of social regulation and integration on suicide rates. This interpretation examined suicide as a social phenomena rather than an individual, psychological problem. By examining situations with too much and too little

social regulation and integration, Durkheim outlined four types of suicide: altruistic, egoistic, fatalistic, and anomic suicide.

Social integration refers to the social support and bonds that tie individuals to the greater society.

Integration facilitates an interaction between the individual and society, enhancing feelings of solidarity and camaraderie. A strongly integrated society “…holds the individual under its control, considers them at its service and thus forbids them to dispose willfully of themselves” (Durkheim 1897 [1997]: 209).

An individual who is too strongly integrated into a society can lose his/her self-identity and value the interests of the greater society over his/her own interests and commit altruistic suicide. On the other extreme, an individual who is not integrated can experience loneliness and a sense of lack of greater purpose and commit egoistic suicide.

The other dimension, social regulation, refers to the social forces and norms that limit humans’ innate, insatiable desires.

A society with too much regulation can constrain individuals too much and force them to commit fatalistic suicide. However, without regulation, Durkheim argues our desires would be both uncontrollable and unsatisfied, leading to perpetual feelings of disappointment and powerlessness. Societies in transition often lack these mechanisms and as a result, individuals begin to have unrealistic expectations and experience dissatisfaction and feelings of meaninglessness and hopelessness. This feeling of normlessness Durkheim called anomie. Anomie and anomic suicide are now among some of the most widely studied concepts in sociology.

Adolescents’ anomic social position

Sociologists have extensively debated Durkheim’s distinction between anomic and egoistic suicide, which he vaguely articulates in his original work. Some have argued that the two concepts measure the same thing and the two dimensions of integration and regulation are coterminous. That is to say, a society cannot be high in integration but low in regulation (Johnson 1965). Yet others maintain that the two are, in fact, separate dimensions. Bearman (1991) argues, “the necessary condition for anomie is that individuals must be integrated into groups and yet not be regulated by normative demands of the group” (513).1

Given this interpretation, adolescents’ social position can be characterized as anomic, that is, highly integrated but lacking in regulation (Bearman 1991). Today’s adolescents are in a unique position between two strong, inescapable social networks—the peer network and the family, both of which can exert strong normative demands on the individual. In this position adolescents experience strong social integration while the conflicting norms and expectations from the two social worlds render the adolescent unregulated by a singular set of normative constraints. The modern adolescent’s social position is distinctly anomic, argues Bearman (1991), because unlike egoists, the adolescent is not lacking in integration, but rather is caught in a liminal state between two increasingly separate worlds of the family and the peer group.

In both, the adolescent is integrated, and therefore subject to the normative demands and regulation of each. But the social worlds of the family and the peer group are frequently independent of each other, and the norms governing action and deportment that each society exerts on the teen are, consequently, often experienced as contradictory…The normative dissonance experienced by the teen is the same as anomie…It is the separation of these two worlds that generates for each the conflicting norms and values to which the individual is subject (Bearman 1991: 517-18).

Thorlindsson and Bjarnason (1998) add that this normative dissonance can enhance the feeling of anomie by also causing an ambiguity in goals.

One may also examine adolescents’ anomic social position by analyzing the structure of their peer network. Unlike the social world of adults, the adolescent social world is characterized as both highly dense (high in integration) yet inclusive of a wide range of interests and norms (low in regulation).

The high density of adolescent social networks is partly due to their separation from the adult world, but also results from the limited ability of adolescents to select their peers. While adults have many different spheres from which to select their friends (work, long-time friends, neighbors), adolescents are largely limited to the pool of peers in their schools.

Rytina and Morgan (1982) simulated a model with 2,000 high school students in a community with a population over age 15 of 50,000. In this model, adults had 500 ties while students, because of their younger age, had 300 ties. Students in this model activated ten percent of two million possible ties, a rate that is ten times greater than that of adults. This rate underestimates the density of students’ social networks because it assumes random contacts, when in fact high schools are stratified by age. If grade stratification is taken into consideration with 600 seniors in the high school and 1400 underclassmen, the internal density for students doubles from 0.1 to 0.2 while the social density for the rest of the community remains at 0.01.

In this simulation, while an adult can reject 99% of his/her fellow adults and still retain 480 potential acquaintances, adolescents would retain only about 20 potential acquaintances if they were equally selective. This restricted selectivity increases the social density of the adolescent social world and can contribute to peer pressure. With more at stake, social rejection and isolation become much more costly. The separation of the high school social world from the adult world, coupled with the limited selectivity of adolescent social networks results in a social world that is more dense and integrated than that of adults.

Because of this high density (high integration), adolescents are simultaneously exposed to a wide range of interests and norms, which can lead to a lack of regulation. Adult social networks generally emerge from shared interests (occupations, hobbies, religion, etc.). As a result, it is more likely that the adults in a given social network already share interests and values.

Conversely, adolescent social networks are generally defined only by a common age group—the school grade. With age as the only common factor, it is more likely that adolescents will meet other adolescents with different interests and norms, some of which may be conflicting. This is yet another source of normative dissonance. This time, the dissonance comes from within the peer network, not from between the peer network and parents. These two sources of normative dissonance (between adults and peers, and from within the peer network) can contribute to a significant lack of regulation.

This interpretation provides a unique lens with which to analyze adolescent suicide ideation that has not been used in previous sociological research. Today, “adolescence [has become] a more distinctive and culturally marked life stage during the second third of this century” (Furstenberg 2000: 898). This model is an attempt to expand and reinterpret Durkheim’s theory of anomie in a way that appreciates the uniquely anomic social position of today’s modern adolescent.

-

II. Suicide suggestion

Perhaps equally compelling yet long seen as a contradictory theory to Durkheim’s theory is suicide suggestion, an extension of Tarde’s (1903) theory of social imitation. This theory argues that suicidality may be influenced by exposure to suicide on both the micro and macrolevels. Suggestion at the microlevel occurs between close friends and family, while suggestion at the macrolevel occurs from suicide coverage in the media. This alternative paradigm has received much attention both for the evidence supporting its validity and also the direct challenge it presents to Durkheim’ s theory of suicide.

Durkheim dismissed theories of suggestion on two grounds. First, he argued that the effects of suggestion are limited to those in the direct vicinity of the individual. Secondly, Durkheim argued that where suggestion is the perceived cause of suicides, suggestion is really the effect of underlying causes related to integration and regulation. That is to say, the perception that one suicide has influenced the suicidality of others is actually the result of underlying social forces that have influenced the suicidality of all of the individuals. Suicides that occur after media coverage were going to occur anyway, but media coverage merely precipitated their occurrence.

Despite Durkheim’s adamant theoretical dismissal of the effect of suggestion, this theory is strongly supported by empirical observations. In the 18th century after the publishing of Goethe’s novel Die Leiden des jungen Werther ( The Sorrows of Young Werther) , there were several young men who committed suicide in the same manner of the novel’s protagonist. Men were even reported as dressing in Werther’s whimsical costume before committing suicide. Although formal investigation into the suggestion effect was never conducted, the novel was banned in several European cities. Because of this social phenomenon the suicide suggestion theory is also called the “Werther effect.”

Macrostudies of suicide suggestion have measured the nationwide suicide rate after media coverage of a suicide and discovered that suicide rates do increase in the year after a real-life or fictitious suicide has been covered in the media (Phillips 1974; Wasserman 1984). Phillips (1974) compared the rise in suicides in New York City and in the rest of the U.S. after a suicide report in the New York Times and found that suicide rates increased significantly more in New York City compared to the remainder of the U.S. After one suicide story was reported on the front cover of the New York Times , suicide rates in New York increased by 25.6% while suicide rates for the rest of the country increased by only 4.5%. Moreover, the increase in suicide rates was strongly associated with the amount of media coverage of a suicide. Suicide rates increased more after a suicide was reported on the front-page than when a suicide story was reported elsewhere in the paper.

There is also evidence that suggestion operates on an individual level and that having a close friend or family member can increase the likelihood of suicidality (Farberow et al. 1987; Tishier 1981). It is unclear whether this pattern within families is a result of social suggestion or biological tendencies inherited from family members. Bjarnason (1994) found that among Icelandic adolescents family support and suicide suggestion are equally associated with suicidality for females, while for males, suicide suggestion has a stronger effect. This microlevel analysis is harder to support because of the difficulty in separating the social and psychological consequences of having a friend or family member attempt suicide.

Despite the empirical support for this paradigm, there remain methodological problems that may undermine these conclusions. While studies suggest a strong association between suicide and suggestion, it is unclear whether these suicides on a macrolevel are actually a consequence of suicide suggestion or geographic clustering. On the microlevel suicide suggestion may operate through inadequate psychiatric support after the suicide of a friend or family. In this sense, suicide suggestion may be a distal rather than a proximate cause of suicide. A suicide attempt by friend or family may render individuals psychologically vulnerable and thus more likely to experience a range of psychological disorders, suicide being one among them. In this case it would be inaccurate to say that suicide has a suggestive effect, but rather it upsets the psychological well being of those near the individual who attempted or committed suicide. Durkheim would further argue that having a friend or relative attempt or commit suicide can upset one’s sense of regulation. In this case, the effect of suicide suggestion would actually be mediated by feelings of anomie.

The nature of suicide as an object of study makes it difficult to determine which mechanism directly influences suicidality. As a result, studies that attempt to separate the direct effects of suicide suggestion and anomie often encounter methodological problems that make it impossible to confidently reject one paradigm over the other.

Although the empirical evidence for suicide suggestion may be theoretically questionable, the implications of this paradigm are culturally significant.

Various countries and the World Health Organization have outlined journalistic codes that dictate how journalists and photographers are to report cases of suicide to minimize their suggestive effect (Norris et al. 2001; WHO 2000).These guidelines recommend that suicide reports not include photographs, nor should they specify the method used or de- tails about the death, such as bridge locations, or specific buildings, nor should they report the suicide as a solution to a personal problem such as bankruptcy or divorce (WHO 2000).

As these journalistic codes demonstrate, regardless of whether the suicide suggestion paradigm is sociologically valid or inferior to Durkheim’ s theory, it has nonetheless been incorporated into the social understanding of suicide.

Other Determinants Of Suicide

Psychologists have studied suicide extensively at the individual level and identified various individual determinants of suicidality. These studies of individual determinants examine suicide ideation, rather than suicide completion, due to the limited individual information available for people who commit suicide. Although these psychological theories emphasize biological and individual factors, many of these determinants can also be examined in a Durkheimian framework. By examining the social position of individuals with these characteristics, one may argue that these characteristics are common to individuals in an increased anomic social position. The relationship between these characteristics and suicide ideation is not causal, but rather one that is mediated through anomie.

For example, individuals of mixed races, Native Americans

(CDC 2004(d); US DHHS 2001), and females (Krug et al. 2002), are all at an increased risk of ideating suicide. Durkheim would argue that this apparent relationship between individual characteristics and suicide could be more accurately explained by looking at the social experiences of members of the group. It could be argued that these individuals inhabit a more anomic social position and it is this that contributes most directly to their risk of suicide ideation.

Native Americans and individuals of mixed races are caught between two strong competing social and cultural worlds, placing them in an anomic social position. They may also experience greater social isolation and less social integration, increasing their likelihood of committing egoistic suicide. Females may be more strongly integrated into their family and also place greater importance on their friendships, increasing the normative influence of these two strong social worlds (Gilligan 1993). As a result conflicts with parents may be more upsetting for females than for males and this may make females more vulnerable to feelings of anomie. This hypothesis is also supported by Bjarnason’s (1994) finding that for females, family support is equally associated with suicidality as is suicide suggestion, while for males family support has less of an effect

It has also been found that intra-family conflicts can lead to adolescent self-derogation and increased suicide ideation for both male and female adolescents (Shagle and Barber 1993).

However, this association can also be explained by looking at the relationship between intra-family conflicts and an adolescent’s sense of anomie. Normative dissonance between the family and the adolescent can enhance feelings of anomie and this normative dissonance can be especially powerful because adolescents cannot leave their families.

The same analytic framework could be used to explain the relationship between childhood physical abuse and later suicide ideation (Kaplan et al. 1998; US DHHS 1999).

Durkheim also used anomie to explain deviant behavior, which is highly correlated with suicide ideation on many dimensions (Stack and Wasserman 1993). An adolescent who feels unregulated by a single set of normative demands may resort to deviant behavior. In this case, deviance is seen as another effect of anomie, like suicide. The same adolescent who feels unregulated and commits deviant acts would also be more likely to ideate suicide. Thus suicide ideation and deviance are not related causally, but rather by a common cause— anomie.

Another social explanation of deviance interprets deviant behavior as a desire to exit adolescence and enter adulthood (Hagan and Wheaton 1993). Such behaviors include premarital sex, alcohol consumption, and drug use. Adolescents, especially female adolescents, who come from unstable households are more likely to exhibit adolescent role exit tendencies and suicide may also be included as an attempt to exit adolescence.

Normative dissonance may contribute to intra-family conflicts and drive an adolescent to seek adolescent role exits, including both deviant behavior and suicide. Thus normative dissonance may influence deviant behaviors through both an explicitly anomic mechanism and through the role-exits theory.

Finally, psychobiological factors, such as mental disorders, especially major depression are a well-established predictor of suicidality. Bertolote et al. (2003) calculated that 53.7% of victims of suicide were diagnosed with depression. Khan et al. (2002) reported that patients suffering from depression have a suicide risk that is 60 to 70 percent greater than that of the general population. Personality disorders such as bipolar disorder have also been related to around 10 to 15 percent of suicide deaths (Rhimer et al. 1990). Strong medical evidence supports the argument that depression has an independent and strong effect on suicidality, but that does not remove the possibility that anomie may contribute to or exacerbate feelings of depression on a social dimension.

This study attempts to test the two dominant sociological paradigms of suicide—(1) Durkheim’s theory of anomie and (2) suicide suggestion. The model in this paper looks at normative dissonance between the adolescent and the adolescent’s two social worlds (the family and the peer network) as an indicator of anomie. Normative dissonance is defined as conflicting norms and behaviors, such as smoking, academic aspirations, and religiosity.

Baseline variables, including the individual characteristics outlined above as well as other variables that may be related to anomie, but not through the mechanism proposed in this paper are included in the full regression model. For example, feelings of parental care, or belonging to clubs and feeling socially accepted at school may contribute to an adolescent’s sense of anomie, but not through the normative dissonance theory in this paper. Variables such as these were included as control variables to ensure that the effect of anomie was specifically due to normative dissonance.

There is also no normative claim as to the behaviors of the respondents. For example, this model is not concerned with whether a student skips class or engages in risky behavior, but is more concerned with whether the adolescent engages in risky behaviors while his/her peers do not. Therefore a student who drinks alcohol and has friends and parents who also drink alcohol would be said to experience no normative dissonance and have little anomie in this sense. Conversely, a student who never drinks alcohol but is exposed to friends and family who frequently drink alcohol would experience significant normative dissonance and greater anomie.

Although there have been studies examining anomie and adolescent suicidality (Bearman and Moody 2004), there has not been a study that looks specifically at normative dissonance as a source of anomie. Bearman and Moody (2004) use friendship transitivity as a source structural dissonance, while this study focuses on normative dissonance. Moreover, this model is prospective, an element which Bearman and Moody (2004) do not include in their model of dissonance. Other studies that relate deviance, anomie, and suicide make normative claims as to the nature of the behavior, but these studies conflate deviance and anomie, something this model seeks to separate.

Methods:

This study uses data from Waves 1 and 2 of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). The sample was based on a stratified, random sample of all U.S. high schools and the study was conducted in three waves. Wave 1 took place between 1994-95 and had two sub-waves: Wave 1a—an in-school interview, and Wave 1b— an in-home interview, which also included an interview with the parents. The school sampling frame included all high schools in the United States if it included an 11th grade and enrolled at least 30 students. High schools were stratified into 80 clusters by region, urbanicity, school size, school type, percent white, percent black, grade span, and curriculum (general, vocational, alternative, special education). 90,118 in-school questionnaires were administered be- tween September 1994 and April 1995. In addition to collecting data on the adolescent’s health, the in-school survey also collected data on the adolescent’s in-school friendship network, which included the adolescent’s five closest male and female friends in the school. These nominations formed the adolescent’s peer network. The in-school friendship data was used to measure normative dissonance between the adolescent and his/her peer network. The in-home sample included

27,000 adolescents, drawing a core sample from each community in addition to oversamples. The core sample included 12,105 adolescents from grades 7-12 in the 1994-5 school year. Groups that were oversampled included students who were disabled, black from well- educated families, Chinese, Cuban, Puerto Rican, living with a twin, full sibling, half sibling, or non-related sibling.

The in-home interviews collected more detailed data from the subsample as well as data on the adolescent’s parents. Data from the parents was used to measure normative dissonance between the adolescent and his/her parents.

20,745 adolescent in-home interviews and 17,700 parent questionnaires were administered between April 1995 and December 1995.

Wave 2 was conducted one year later and had the same in- home sample from the Wave I in-home interview sample except for seniors.

In this wave contextual information was also collected, including information about neighborhoods and communities. 14,738 adolescent in-home interviews were administered between April 1996 and August 1996.

Wave 3 was completed in 2000-01 and the sample included Wave I respondents who were available for interview. This wave also collected high school transcripts as well as urine and saliva samples. Between July 2001 and April 2002 15,197 young adult in-home interviews were conducted. Data from Wave 3 was not included in this study. Only those students who had participated in both stages of Wave 1, answered the question regarding suicide contemplation in Wave 2, and whose parents participated in the in-home interview were included in this study, bringing the sample size down to n=7578.

The dependent variable, suicide ideation, was taken from Wave 2 and all other independent variables were either directly taken from or created from data in Wave 1. The independent variables of the multivariate regression model measured normativedissonance (anomie) from both the adolescent’s parents (parental anomie) and peer network (peer network anomie). Other baseline variables and demographic variables were included, such as sex, age, family stability, depression, and having a friend or family member attempt or commit suicide. Details on how and when each variable was measured are found in Appendix A.

Independent Variables

The variables measuring anomie from the parents and peer network were created by comparing the adolescent’s responses to a given set of questions to those of his/her parents and peers from Wave

-

1 surveys. Because the parents and peers answered different surveys, it was impossible to compare the two groups directly. While parents answered questions regarding smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, sex, and religion, peers answered questions regarding smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, deviant behavior, family relations, and social integration. The two interviews overlapped on too few dimensions to allow for a substantive comparison.

Parental Anomie Variable

For the adolescent-parent comparison, the absolute difference in responses to questions regarding smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, sex, and religion was calculated. These questions best reflect the norms and behaviors of the respondents and were most conducive to comparison.

Moreover, these questions reflect both explicit expectations and implicit norms as reflected in the respondents’ behavior. For example, a parent’s voiced expectation that he/she wants the adolescent to go to college obviously exerts influence on the adolescent, but equally important are the norms that are conveyed implicitly through the parent’s actions, such as smoking, drinking, and religiosity. A full description of questions used in the adolescent- parent comparison is found in Appendix B.

For each variable, the absolute difference between the adolescent’s response and the parent’s response was calculated. This number measured the discordance for that individual variable. All of the measures of discordance were averaged to yield a single measure of parental anomie. nominated correspond to his/her ego-send network . Those students that nominated the adolescent correspond to his/her ego-receive network . The group of students who nominated and/or were nominated by the adolescent correspond to his/her send-and-receive network . This study used data from the ego-send network. It is more likely that those students whom the adolescent identifies as his/her close friends will exert the greatest normative influence. Nominating a student as a friend is an indication of approval of the student, which entails, to a certain degree, approval or at least acceptance of that student’s norms and behaviors. Conversely, students who nominate the adolescent may not necessarily enjoy approval or acceptance by the adolescent and may not be in a position to influence the adolescent.

In this comparison, questions regarding smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, deviant behavior, family relations, and social integration were used. Again, these questions reflect both the explicit norms of the respondent, such as academic aspirations, as well as those implicit norms that are reflected through behaviors, such as alcohol consumption. Moreover, the questions measuring family relations reflect the overall sense of adolescent-family relations that may permeate through the adolescent’s peer network and subsequently influence the adolescent’ s relationship with his/her family.A full description of questions used in the adolescent-peer network comparison is found in

Results

From the bivariate analysis (reported in Appendix D), several determinants were significantly associated with suicide ideation. Significant risk factors included being female (OR=1.98), having a family member (OR=2.95) or friend (OR=2.87) attempt suicide in the past year, having negative expectations of the future (OR=1.26), having poor health (OR=1.45), depression (OR=2.01), and experiencing normative dissonance from one’s parents (parental anomie) (OR=3.37). Normative dissonance from the peer network (peer network anomie) was not associated with suicide ideation (OR=0.53).

Significant protectors against suicide ideation included having a high grade point average (OR=0.81), feeling that his/her parents care for him/her (OR=0.56), having high self-confidence (OR=0.54), and feeling socially integrated into the school (OR=0.61).

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

In the multivariate logistic regression model (reported in Appendix E), many of the variables’ independent effect on suicide ideation decreased significantly. While the effect of parental anomie also decreased in the full model, of all of the variables, parental anomie had the greatest odds ratio (OR=2.74). These associations may suggest that the control variables that had significant bivariate associations with suicide ideation may have been mediated through another variable, such as parental anomie or depression. The effect of parental anomie decreased by 19%; the effect of having a family member attempt suicide decreased by 44%; the effect of having a friend attempt suicide decreased by 30%; and the effect of depression decreased by 16%. Of all of the variables in the bivariate model, the effect of depression decreased the least in the full-regression model, suggesting depression independently affects suicide ideation. Peer network anomie continued to have no significant impact on suicide ideation.

The significant risk factors in the full regression model included depression (OR=1.69), not trying hard in school (OR=1.29) and having a family member (OR=1.65) or friend (OR=2.02) attempt suicide in the past year. Surprisingly, although peer network anomie did not have a significant effect on suicide ideation, having a friend attempt suicide had a greater effect on suicide ideation than did having a family member attempt suicide.

Variables that remained protectors against suicide ideation in the full regression model included older age (OR=0.82), thinking his/her parents care for him/her (OR=0.79), and having high self- confidence (OR=0.80). In balance, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that parental anomie has a strong effect on suicide ideation, supporting the more general hypothesis that adolescent-parent relations are a significant factor in suicide ideation.

One surprising demographic variable that became an insignificant variable in the full regression model was sex. While in the bivariate analysis being female had a strong and significant effect on suicide (OR=1.98), in the full regression model, the effect was insignificant. To isolate the specific effect of confounding variables, the full regression model was repeated with specific variables eliminated. From these tests it was discovered that depression and suicide suggestion from friends were the two strongest confounding factors between being female and suicide ideation. Running the full regression model without depression, the effect of sex became significant (OR=1.69).

When running the full regression model without the effect of suicide suggestion from friends, being female again emerged as a significant variable (OR=1.38). Parental anomie did little to account for the diminished effect of sex on suicide ideation. It was further hypothesized that since it has been argued that interpersonal relations are more important for females than for males (Gilligan 1993), there would be an interaction between sex and parental anomie. Findings from these interaction tests were insignificant.

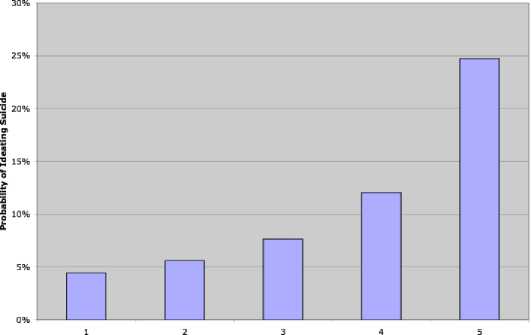

The independent effect of parental anomie on suicide ideation can be further examined by looking at the sample and calculating the predicted probability of ideating suicide with no anomie and full anomie. To do this, the parental anomie measure was divided into quintiles and the probability of ideating suicide for each quintile was predicted. The model predicted that an adolescent with no parental anomie would have an 8.7% probability of ideating suicide, while an adolescent with full parental anomie would have a 14.4% chance of ideating suicide. These predicted probabilities are compared to the observed percentages in Table 1.

To control for the effect of confounding variables that may contribute to anomie and suicide but not through the normative dissonance theory, the full regression model also included measures of perceived parental care, living with both parents, participation in school clubs, feelings of social integration at school, optimism about the future, and selfconfidence.

This wide range of potentially confounding variables included in the model reduces the likelihood that there is another significant variable that could be strongly associated with both parental anomie and suicide. Yet the possibility remains that there is another variable that operates on both parental anomie and suicide that is not included in this model or in the theoretical framework of this study.

Because the effect of depression on suicide ideation was diminished the least in the full regression model, depression and parental anomie seem to operate somewhat independently on suicide ideation. To further analyze the independent effect of depression on suicide ideation, the probability of ideating suicide given no depression and full depression was calculated. The measure of depression was divided into quintiles and the predicted probability of ideating suicide was calculated. An adolescent with absolutely no depression has a 4.4% of ideating suicide, while an adolescent experiencing the maximum amount of depression has a 24.7% chance of ideating suicide.

Figure 2. Probability of ideating suicide by depression quintiles.

Depression by Quintile

These predicted probabilities differ dramatically from the predicted probabilities from the parental anomie test. The wider range of predicted probabilities of ideating suicide in the depression analysis suggest that depression may have a stronger independent effect on suicide ideation than parental anomie. The full logistic regression model predicted that if depression were eliminated from the sample, the suicide ideation rate would drop to below 5% while if parental anomie were eliminated, the suicide ideation rate would only drop to around 9%.

Conclusions

Previous sociological studies of suicide have focused on the general population and there has been little attention to the unique social position of adolescents. Moreover, there have not been many studies that have attempted to test the two dominant sociological paradigms for understanding suicidality in a single model, particularly as it pertains to adolescents. This study fills in both gaps by recognizing the special position adolescents hold between two competing social worlds and by addressing the debate between Durkheim’s theory of anomie and the theory of suicide suggestion on the microlevel.

The full regression model reveals that parental anomie, as experienced as normative dissonance between the adolescent and the parents, has a significant effect on adolescent suicide ideation, greater than that of suicide suggestion from friends and family members. The strong effect of parental anomie challenges theories of suicide suggestion and also theories of the effects of peer pressure on adolescents’ sense of regulation. Depression appears to have a strong and independent effect on suicide ideation. This was not surprising and does not substantially influence the discussion regarding the two sociological theories of suicide.

The diminished effect of suicide suggestion in the full regression model suggests that the effects of suicide suggestion operate most significantly through an adolescent’s experience of normative dissonance with his/her parents and other mediating variables. While this model does not explain the specific relationship between suicide suggestion and anomie, it does suggest that Durkheim’s theory of anomie is a more useful paradigm than suicide suggestion.

However, the significant effect of suicide suggestion in both the bivariate and full logistic regression analyses supports the findings of previous research supporting the suicide suggestion paradigm. Given the strong association between suicide ideation and both anomie and suicide suggestion, it may be more helpful to view suicide suggestion as a complementary, rather than a competing paradigm to Durkheim’s theory, as Skog (1991) and Bjarnason (1994) argue.

While friendships are undoubtedly important for adolescents, these findings suggest that friends with different norms and values do not exert as much normative influence on an adolescent as previously believed. An alternative explanation is that adolescents are more resilient to normative dissonance from their peer network than from their parents because they may select their friends while they cannot escape their parents. Future studies on the mechanisms of and degree to which peer pressure operates in today’s adolescent peer networks would be helpful in drawing more conclusions. Bearman and Moody (2004) examine the structure of friendships, particularly friendship intransitivity. A hybrid approach that includes Bearman and Moody’s (2004) analysis of friendship structures with consideration of the friends’ norms and behaviors could reveal more specific information on the mechanism through which friends exert normative influence on adolescents.

Although peer network anomie had no effect on suicide ideation, having a friend attempt suicide had a greater effect on suicide ideation for both males and females than did having a family member attempt suicide.

This seemingly contradictory finding may be explained by Cialdini’s (2001) theory of social proof.

Suicide suggestion may be stronger from friends because adolescents are more likely to identify with individuals who are similar to them. One could also argue that this association is not necessarily causal. Rather than interpret the data to suggest that having a friend attempt suicide influences suicide ideation more than does having a family member attempt suicide, one could argue that people’s reactions to having a friend attempt suicide differs from that of having a family member attempt suicide. After a family member attempts suicide, the family is often brought closer, providing greater support for the adolescent. This solidarity reaction may not be as strong when a friend attempts suicide. In this way, the family is better equipped to deal with a suicide attempt whereas a friendship network may not be able to react as effectively to an attempted suicide.

It is important to mention that the different effects of parental and peer network anomie on suicide ideation could be due to the construction of the anomie variables in this study.

Because of constraints from the Add Health surveys, the two anomie variables measured normative dissonance along different dimensions. While the parental anomie variable measured norms and values along the dimensions of smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, sex, and religion, the peer network anomie variable measured norms and values along the dimensions of smoking, alcohol consumption, academic aspirations, deviant behavior, family relations, and social integration. It could be argued that the parental anomie variable more accurately measured norms and values, while the peer network anomie variable measured the behaviors of the adolescent, which may or may not reflect norms and values.

A future study that constructs two comparable anomie variables would better identify the different effects of anomie from the parents and peer network. Such a model would also allow for direct comparison of norms and values between the parents and peer network, something this model is unable to do. Instead, this model measures normative dissonance as experienced separately between the adolescent and his/parents and peer network.

Although interactions between sex and anomie did not result in any significant findings in this study, the strength of the effect of anomie on suicide ideation across sexes should be further explored. The insignificant findings in this study may be due to the converging socialization of males and females in today’s schools. Although it has been previously observed that interpersonal relations are more important for females than males (Gilligan 1993), this generation of adolescents may share similar, less gendered social experiences in schools.

The strong effect of normative dissonance between an dolescent and his/her parents on suicide ideation reveals significant potential areas in which Durkheim’s theory of suicide may be expanded.

The findings in this study make a strong case for greater consideration of social factors, including anomie, on depression. Examining the specific interactions between anomie and depression as well as anomie and suicide suggestion could expand Durkheim’s original theory to be reconciled with other dominant theories as well as invigorate a dialogue across social sciences.

These findings have challenged many previous understandings of suicide, adolescent social experiences, and the in- tersection between psychological and social factors and their effects on suicide ideation. Given the limitations of the data and methods used, one can only speculate as to the theories that may explain these findings.

To understand the specific mechanism of the relationship revealed in these findings, further research is necessary.

The conclusions of this research have significant implications for suicide prevention policies.

The strong independent effect of depression on suicide suggests that reducing depression may be the most effective way of decreasing suicide ideation. However, this does not mean that other social factors should be ignored. The social variables of depression should be further studied to better understand how normative dissonance interacts with depression.

This better understanding would help psychologists and parents identify specific factors of depression and target intervention. Although the suicide suggestion paradigm has already been incorporated in some policies, on the microlevel it appears that focusing on normative dissonance may be a more effective and efficient means of addressing adolescent suicide ideation. This is partly due to the greater number of adolescents who experience parental anomie and also the greater effect of parental anomie compared to suicide suggestion.

At a more basic level, unlike depression and suicide suggestion, normative dissonance is an important variable that may be addressed preemptively and without drastic interventions.

As this study suggests, suicide ideation can be influenced by simple measures such as greater communication and compromise between parents and adolescents.

Suicide prevention strategies need not be limited to institutionalized or medicalized means, but can be incorporated into daily activities that can positively influence the modern adolescent’s social experience.

Appendix B: Questions used for adolescent-parent comparison

|

Adolescent Questions |

Parent Questions |

|

|

Smoking |

Have you ever smoked cigarettes days)? |

regularly (at least 1 per day for 30 Do you smoke? |

|

Alcohol |

Do you ever drink beer, wine, or liquor when you are not with your How often do you drink alcohol? Parents or other adults in your family? Over the past 12 months, on how How often in the last month have many days did you drink five or you had five or more drinks on one more drinks in a row? Occasion? |

|

|

Academic aspirations |

On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is low high, how much do you college? College? |

How disappointed would you be if and 5 is {Name} did not graduate from want to go to |

|

Sex |

How much do you disapprove of Have you ever had sexual {Name}'s having sexual intercourse? intercourse at this time in (his/her) Life? |

|

|

Religion |

How important is religion to you? How often do you pray? |

How important is religion to you? How often do you pray? |

Appendix C: Questions used for adolescent-peer network comparison

Variable Question

During the past year how often did you smoke Smoking cigarettes?

Have you ever had a drink of beer, win, or liquor more than two or three times in your life?

Alcohol

During the past year how often did you drink alcohol?

During the past year how often did you get drunk?

How hard do you try to do your schoolwork well?

During the past year how often did you skip school

Academic Aspirations without an excuse?

Grade point average.

During the past year how often did you race on a bike, skateboard, rollerblades, or in a boat or car?

During the past year how often did you do something

Deviant Behavior because you were dared to?

In the past year how often have you gotten into a physical fight?

During the past year how often did you lie to your parents?

Family relations How much student feels like mother cares about him/her.

How much student feels like father cares about him/her.

Student feels socially accepted.

Student feels loved and wanted.

Social integration

Student is happy to be at this school.

Student feels like a part of this school.