Norwegian-Russian Arctic frontier: from the whole districts to the Pomor region

Автор: Zaikov К.S., Nilsen I.P.

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Geopolitics

Статья в выпуске: 5, 2012 года.

Бесплатный доступ

In the present article the authors analyse the history of the Norwegian-Russian state border. Three main periods are pointed out. In the middle ages and Early Modern Period there existed a large frontier or common taxation district. Thence the common district gradually shrank until in 1826 a permanent territorial border was drawn. In the Soviet epoch the border became almost hermetically closed. To-day it is again opening up and politicians and researchers on both sides are discussing the possibility of establishing a joint Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a new and modern form of “common district”.

The Russian-Norwegian border, the Pomor zone, the general districts, history, the Russian-Norwegian relations

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148320467

IDR: 148320467 | УДК: 327(470+481)(091)(045)

Текст научной статьи Norwegian-Russian Arctic frontier: from the whole districts to the Pomor region

The idea of creating special economic zones (SEZ), the so-called "zone of the Pomeranian" decay splits along the subarctic Barents Sea coast in the border area between Norway and Russia, is an initiative, recently adopted by the governments of both countries [1, 2009]. However, in the history of Russian-Norwegian border relations the idea of a common border area is not new. In the XVIII - early XIX centuries, the prototype of the modern Pomeranian zone, a single micro region was a space of "general district" (South Varanger), which included the territory of the modern location of the Norwegian-Russian border. The common space has developed in the Middle Ages, and it was a lot more territory, "district» XIX century. Geographically, they cover the whole of Finnmark ("Sami land") - the coastline, about the modern Tromso in northern Norway to the White Sea in the east, as well as vast areas in the interior of North Fennoskandinavii and the Kola

Peninsula. Designated space corresponds to the territory which we now call North Caloto (Arctic), including, in the broadest sense, also the Kola Peninsula. Originally the area was homogeneous. Up until the XIII century Finnmark was a single cultural region with a low density of the indigenous Sami population. Between different Sami siytami and their territories, of course, there were boundaries, but this area was boundless in the sense that there existed no boundaries between the states [2, p. 31-95].

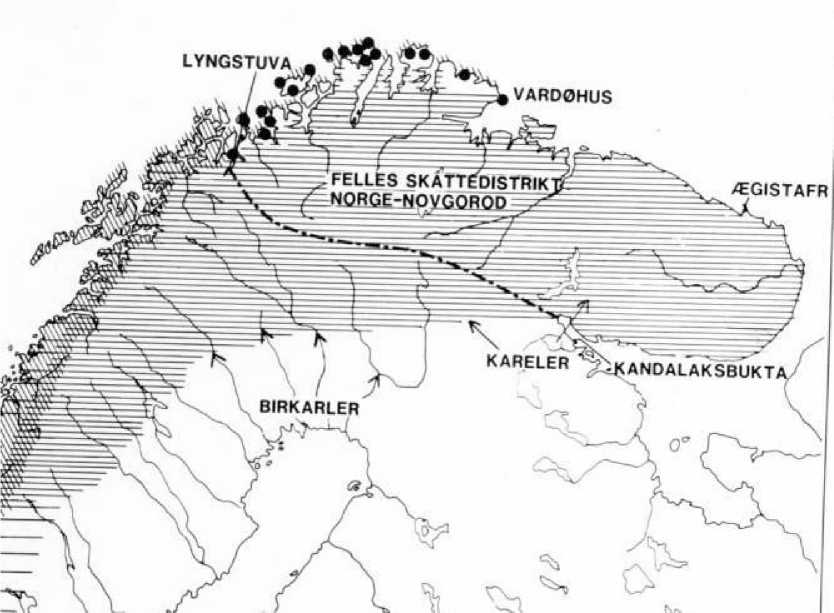

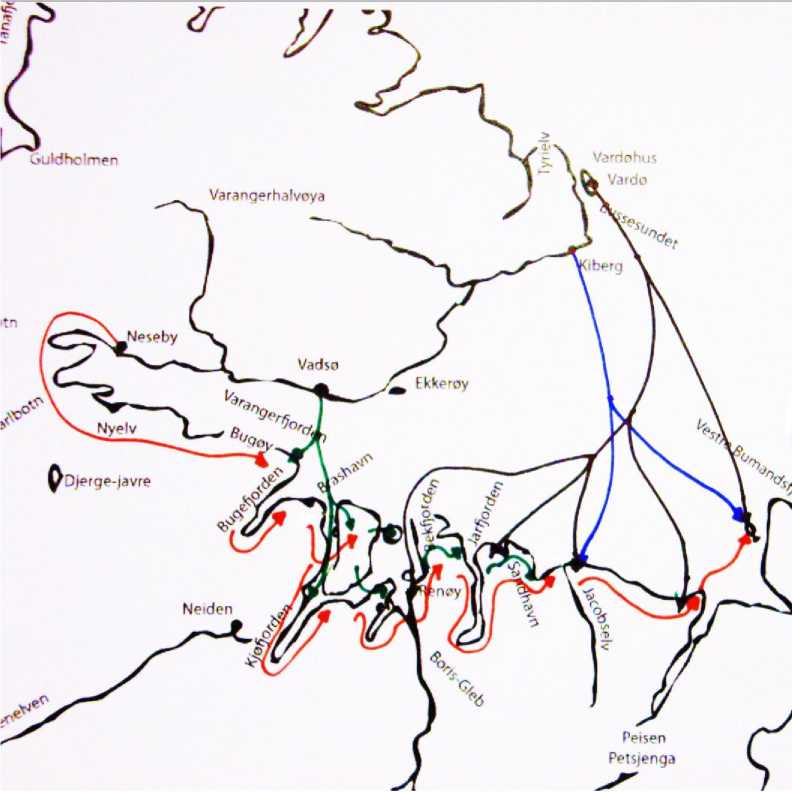

Pic. 1. On the map 1 depicted a little bit last periods. The black points mean точки Norwegian fishing settlements along the coast

Before analyzing the historical dynamics of Russian-Norwegian border region turn to categories such as the border, the state and society, relationship between the border and the state, the values of the boundaries for society as a whole.

The demarcation of borders and the maintenance was and probably still is the primary task of the modern state. Therefore, one of the fundamental characteristics of sovereignty is the ability and willingness of the state for the lines of the boundaries between their own territory and the territories of neighboring countries, the introduction of rules governing the flow of goods and people across the established boundaries, underscoring of national independence and exclusivity. At the same time it is clear that the precise delineation of territorial boundaries by not a universal feature of all societies that have existed at all times. The ability to maintain border demarcation and especially characteristic of modern society and is the culmination of a century of development, when the value of the boundaries changed with the changing social structure of society.

At first, in Europe there was no precise boundary lines, and was attended by only a border or transit zone between the kingdoms in the guise of forest and desert areas. Problems with boundaries were one of the main characteristics of the feudal era, which has never existed geographically clearly defined political subjects [3, 1992]. Gradually vague power relations in the sphere of sovereignty of the subjects changed more precise definitions of property rights and areas of jurisdiction of the authority. This change was confirmed with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, when it was formulated by the well-known doctrine of the state as an independent political entity. The great European powers agreed to respect the principle of territorial integrity. For the first time the state was made to the forefront as a guarantor of internal order, the owner and artist of the principle of territorial sovereignty. However, in early modern times the rulers have often lacked accurate information about their own country: the number of population, natural resources, and the amount of possessions. Even when the need was recognized in the state borders, the establishment of boundaries was a matter quite problematic [4, 1986].

Systematic mapping of the physical landscape, the study of natural resources, use of maps and statistics have been widely used in Europe only since the beginning of the XVIII century. Establish boundaries, indicating the territory of the state, are easier from a practical point of view. Nevertheless, the need for territorial control and clear physical boundaries even further increased in the XIX century. This was due to the spread of ideas of "popular sovereignty" and "nationstate." While the language and culture are increasingly becoming instruments of national integration, further increased the need and clearly defined boundaries. Now the boundary formed physical and political limits of national and cultural entities, keeping their integrity and protection from external infiltration [5, 1997].

The North Calot in the early Middle Ages was a boundless field, in the sense that there existed state borders. Later this area became a single stream of European development, and within a few centuries, this has led to the formation of nations, separated by lines of permanent borders, conducted by neighboring states. To some extent, the region deviated from the common European model of the evolution of boundaries. His main distinction was that the border line in the European North was conducted quite late relative to other European micro-regions. For example, permanent Norwegian-Swedish (or, rather, Norwegian and Swedish-Finnish) in the northern border of Calot was first established only in 1751, and the Norwegian-Russian (or Russian-Norwegian and Finnish), the boundary only in 1826, that is less than 200 years ago. How can we explain such a delay in the demarcation of boundaries in the far north of Europe?

There are several factors that have hampered the precise delimitation and demarcation lines of conduct. One of the important factors that probably was a huge extent of the North Calo-to. Another factor was the weak density of population and its peripheral location relative to the center. Reigning actors took a long time for the control of the territory by building churches, colonization, create a system of ecclesiastical and secular government. And, perhaps, the state did not seek to hasten the establishment of boundaries, because they wished territorial expansion [2, p. 31-95].

Without a doubt, the Sami culture and the question of economic adaptation of the Sami were also very important. The traditional Sami culture of fishing based on extensive use of the land. Since the beginning of spring with the nomadic Sami wintering sites in the interior of the region and beyond to the summer parking along the coasts of seas and rivers to the most efficient use of natural resources in different seasons. In the autumn they may be in other areas habitat.

With the proliferation in the XVII century the importance of reindeer herding Sami nomadic economy have increased.

Perhaps it was a unique phenomenon in Northern Europe of the XIX century, but it is known that such a situation encountered in other parts of the world where the predominant population of the nomadic way of life. For example, a similar form of semi-nomadic economy, and met with Mongolian tribes who moved cyclically through the China-Mongolian border, which is in the middle of the XX century, wrote anthropologist Owen Lattimore. For the Mongolian nomads pasture taken separately did not represent a value, because the rapidly dwindled. On the contrary, the right to travel was much more important than the right to stay in one place [6, p. 534]. Also for the Sami decisive factor was the preservation of the rights of free movement. Carrying out the boundaries in the North Caloto could create barriers to traditional routes. Without a doubt, the annual cycle of the Saami migrations slowed the process of installing permanent borders.

Instead of defining the territorial borders of Norway and Russia for many centuries, were reconciled with the existence of huge public lands where the State's right to tax was not tied to a particular territory and to specific groups of Sami [2, p. 31-95]. This allowed us to collect taxes from the Sami, where they were in a certain season of the year without a loss to the state treasury. Binding of fiscal jurisdiction to ethnicity, rather than to a particular physical space, was the essence of the border treaty signed between the Norwegian king and grand prince of Novgorod in 13261.

Since the beginning of migration of the more developed nations of southern Scandinavia, Finland and Russia shared the Norwegian-Russian possessions were gradually reduced. New settlers created their own economic space, integrating the new land that eventually became a continuation of the national territory. The rivalry between them has led to that the Sami have to charge more taxes. It was believed that the more able to collect the tax, the greater the rights to the land. Later, the king of Sweden presented the claim to a common territory, referring to the so-tax collection, they were called birkarlerami in the late Middle Ages. In the second half of the XVI century, the coastal Sami in northern Norway had to pay taxes to three different rulers - Danish-Norwegian king, king of Sweden and the Russian Czar [7, p. 40-61].

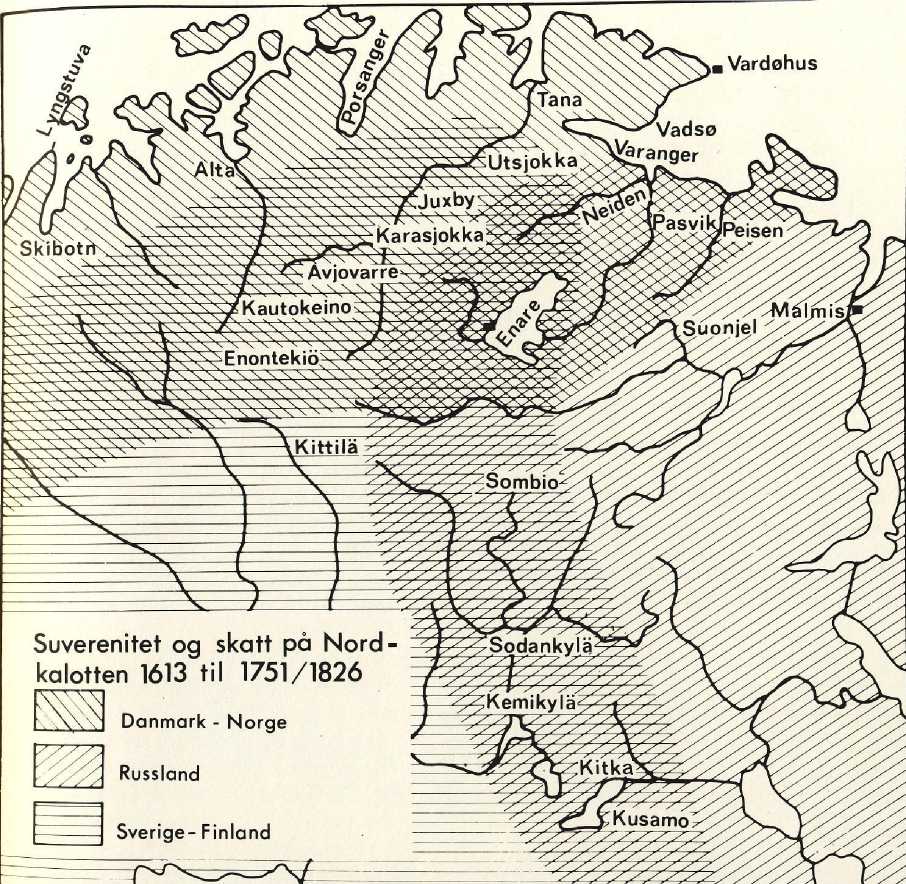

Pic. 2. The shaded area shown on the map of fiscal sovereignty and jurisdiction of Denmark - Norway, Russia and Sweden – Finland.

During the XVII and XVIII centuries the territory of "general district" was gradually reduced. The war years 1611-1613 (Kalmar War) between Denmark - Norway and Sweden was associated primarily with the question of how the state will monitor the coast of Finnmark. After losing the war, Sweden had to leave the coastal areas of Finnmark. Only in 1751 was set to a constant state border between Sweden and Norway on the plateau Finnmarksvidda. After the conquest of Russia in Finland in 1808-1809 and the subsequent peace treaty was signed in Hamina Sweden had to give up its right to collect taxes in the area of Enar.

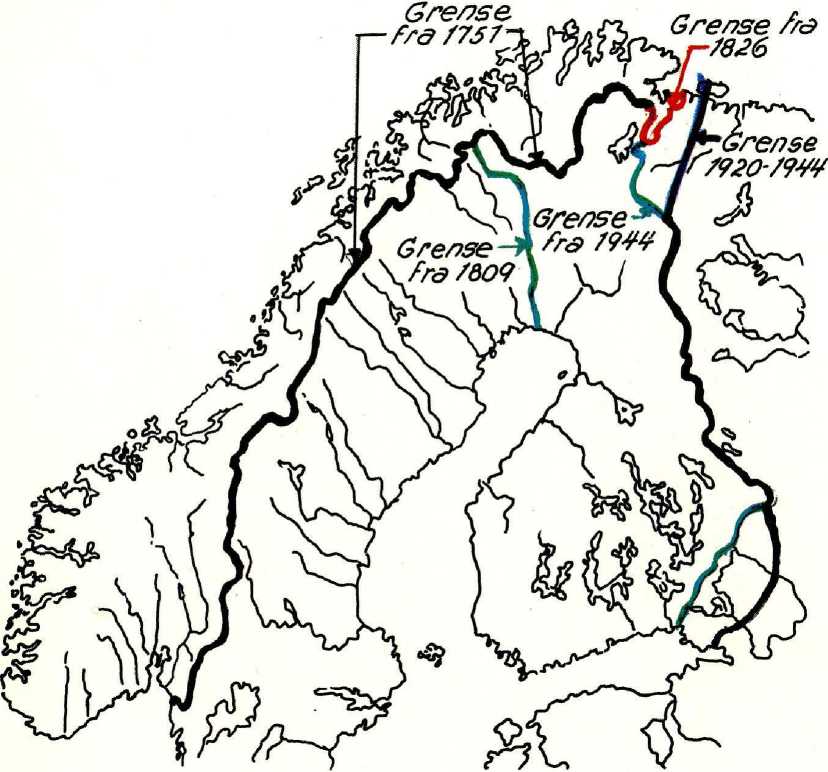

Pic. 3. On the map marked dates of founding state borders

After that, from the initial public lands there was only a small strip of land in Varanger, which was a joint Norwegian-Russian possession.

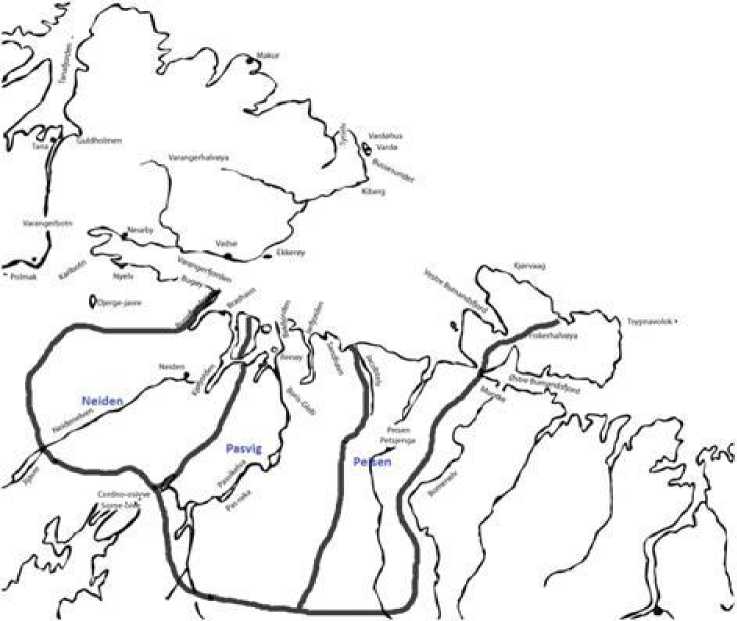

Рис. 4. On the picture marked outer borders of the common Russian - Norwegian counties, as well as the borders of 3 saams siits, whose territories were shared districts.

Semi-nomadic life of Norwegian and Russian, have migrated to the total area for a long time creating obstacles to the demarcation of the "general district" between Norway and Russia [8, p. 8]. However, a weak fiscal control over the territory of counties with a total Norwegian and Russian sides contributed to the formation of the free, buffer zone, the physical boundaries of which have become symbolic boundaries siyt (graveyards) of the eastern Sami (Skolt).

To form the prerequisites for differentiation of these common possessions of great importance was the expansion of the church from the east and west. With the penetration of the XVI century, Protestant and Orthodox churches in the population of «general district» were gradually Christianized. The indigenous people of the South Varanger, Skolt, accepted orthodoxy, recognized the de facto citizens of Russia and its north-western neighbors, mountain and sea of the North Varanger Sami, adopting Protestantism, became subjects of Norway [9, Johnsen O. A., Nikolsky, VN]. Since the physical space of "general district" has become a political and cultural frontier of Norway and Russia.

Pic. 5. Red arrows indicate the direction of migration of Norwegian Sami, black - areas of economic activity Norwegian garrison Vadrehusyu. Green arrow indicated areas of economic activity of Norwegian settlers from Vadsø, blue - areas of economic activity of Norwegian settlers from Kiberga.

The extensive nature of the mountain herding Sami, a convention of political boundaries are gradually led to an increase in migration of Norwegian citizens in the Skolt the middle of the XVIII century. In the same period there was intensive development of the Norwegian settlers of the North Varanger (settlements Varde, Vadsø Kiberg) of natural resources "general constituencies" [10, p. 39-46].

The absence of the institute boundaries, convenient geographical location of graveyards Skolt, high tolerance to the presence of Russian Sami and Norwegian subjects provided an opportunity to merchants and Pomorie Norwegian, Russian and Norwegian Sami trade freely and conduct joint business activities without hindrance from the authorities of both nations. Already in the XVIII century the territory of South Varanger was a transit zone, where every year since the beginning of the summer came Russian and Norwegian industrialists, merchants barter for the product. Depended on supplies from the province of Finnmark and the Arkhangelsk region of grain, cloth, tools, metal products and luxury goods Skolt willingly played the role of intermediary in trade between the Norwegian merchants and Pomorie. Living between two asymmetric centers on the scale of forces, different socio-cultural communities (Protestant, Orthodox and Western Europe, Eurasia) Skolt tried to integrate in both directions of Russian-Norwegian frontier. While

Norway and Russia is gradually came to the idea of setting limits to the Institute of XVIII - early XIX centuries, the Sami constructed image of a "general district" as a unified socio-cultural community, multicultural micro region.

Skolts were dvoedantsi, but they did not identify himself with the citizens of Norway and Russia. Aware of their borderline position, they tried to balance between the two powers. Depending on the Norwegian and Russian threats to both sides of the Sami used in solving economic problems, while retaining their social and cultural integrity and identity of designing a special border. Playing the role of contracting in the economic integration of the Arkhangelsk region and the province of Finnmark, Lapps were a factor in the design of the general attraction of the area where experienced economic and political interests of Russia and Norway.

Unclear legal status has been beneficial to the population of neighboring regional entities of the two countries, but the fact of "general district" caused great concern among the authorities of Denmark - Norway, because it was thought that the kingdom could easily be drawn into the conflict with great power - the Russian Empire. The most important task was to conclude a treaty on the demarcation line, which once and for all would determine which ended in Norway and Russia began. Good neighbors in need and in good fences. Russia, by contrast, did not hurry with the division and for various reasons, preferred to take a wait and see. We know that the Danish-Norwegian authorities have regularly turned to the Russian government on this issue, but it did not lead to the desired result [11]. In principle, the Russian government did not prevent solution of the problem, but has always had an excuse to postpone it. Why Russia has been so cautious?

Probably some of this can be explained by asymmetric neighborhood relations, ie relations between small and great powers. This required great attention to the neighborhood and wants a clear separation of the small state, then as a great power did not show similar motives. Another approach is explained by the fact that the Russian Empire (autocracy) lagged behind the political development in Western Europe. Like other empires of the past, Russia is not particularly interested in the establishment of clear boundaries to the surrounding countries. Lack of synchrony in the time development between East and West may have been particularly noticeable in the far north, in the only place where Russia is directly in contact with Western Europe without a zone located between the Eastern and Central European nations. Far North was the area where two different systems of government, as it were fused together, a place where it was about two different concepts of the border. On the one hand, it is developing a small nation state with a strong need to control its own territory, but on the other - a huge, multinational, dynastic state, more tolerant to the transparent borders.

The uncertainty in the territorial size of Tsarist Russia is associated with a relative sense of distance, borders and places in the Russian culture. This is not necessarily perceived as a weakness, or was it a weakness that could result in a symbolic force. Russian poets, who sang in the XVIII century, the Empress Catherine II, mentioned the huge size of the country as its most important feature, a symbol of power and grandeur. Simply put, Russia was so powerful and extended over long distances, such that its boundaries could not be clearly identified [12, Medvedev S. A., Tolz Vera, Berdyayev N.]. The Russian force of gravity was in itself so great that there was no need to set clear boundaries in all parts of the empire, or spend money to strengthen the sov- ereignty of the state in the peripheral regions. Unlike Norway, Russia could continue to exist with vague and uncertain boundaries in the North West.

Basis for the resolution of the Norwegian-Russian border issue arose only at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when there was a rapprochement between Russia and Sweden after a period of cool relations caused by the Russian conquest of Finland. In 1812 Tsar Alexander I signed a contract with the Swedish heir Karl Johan. This meant that Sweden has not had any hope of return to Finland (so, at least, the treaty was perceived in Russia). In return, Russia promised to support Sweden in its desire to liberate Norway from Denmark and Norway in the subsequent union with Sweden. "Agreement 1812" and further the brotherhood of arms in the war against Napoleon was the beginning of a long period of official Russian-Swedish friendship. Russian tsar's favor with respect to Sweden - Norway has led to the ratification of border treaty in 1826, which was quite profitable for Norway. It seems that the negotiations the king did not take into account the skepticism of the new Finnish and Russian Lapps, as well as the public Archangel of the North.

Norway and Russia were willing to consider the legal enshrinement of "general constituencies" status of a special zone of economic interests of the indigenous population only after the finalization of the boundaries of internal sovereignty. Initially, the two powers had to destroy the old buffer zone in order to reconstruct it again, but in the framework of existing international law, public interest and the internal rules. Legal implementation of a common economic area with public authorities responsible for control of the border population and economic activity was carried out only after the ratification of the border in the 1826 convention. According to the articles of the Convention were adopted special rules to guarantee the special rights and privileges for cross-border indigenous people to fish in the neighboring state [13, p. 154-155].

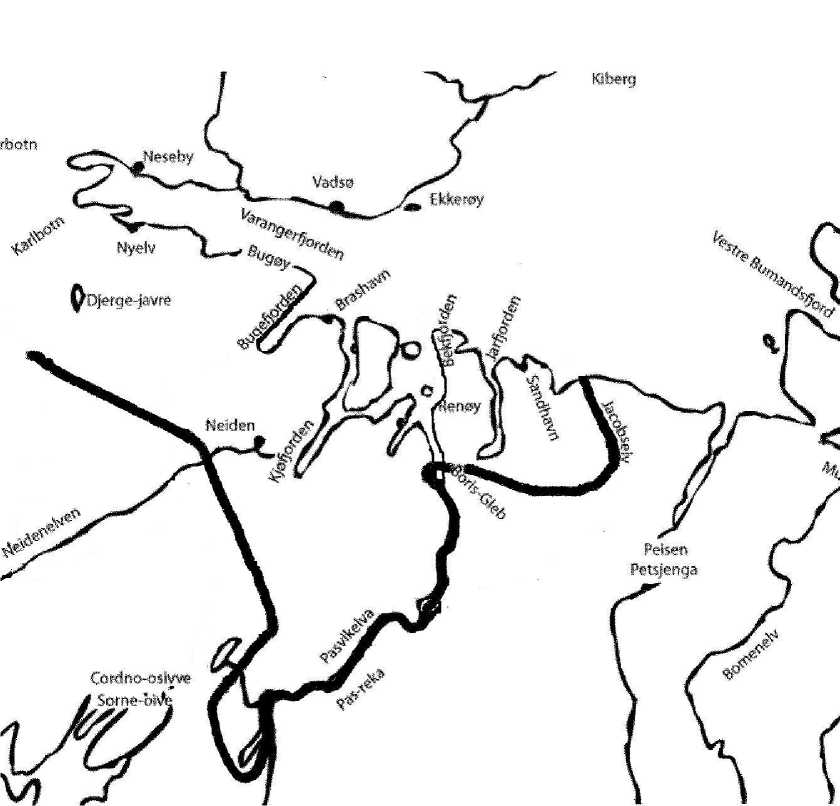

Pic. 6. Black line indicated the state border between the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden to the Russian Empire, established by the Convention for the Border 1826

Although the scope of rights granted under the Sami Article 7 Border Convention, 1834 has been reduced and had narrowed the geographical areas of implementation, the existence of a single micro region continued until 1917. With the onset of civil war in Russia in the Far North have been significant geopolitical changes. Finland gained its independence in 1920 received from Soviet Russia Pechenga. In the next twenty years in the Norwegian-Russian border was the Norwegian and Finnish. September 19, 1944 on the result of the Moscow Armistice Pechenga area was returned to the Soviet Union. There has been a revival of the Norwegian-Russian border. Her line of repeat architecture of the border line established by the Convention in 1826, but the ideological differences between the new state actors (the Kingdom of Norway and the Soviet Union) led to a reduction of border institutions in charge of the execution of an additional protocol in 1834 [14, p. 80-104]. The new regime of tight boundaries existed for over 40 years. This is clearly reflected ideologically picture of the world at that time and the cold war.

But times have changed, and after the Cold War, the development has gone in the opposite direction. Today, many believe that the nation-state weakens or changes its character and that this could lead to territorial systems with fuzzy boundaries. If so, then it will affect Russia's borders? Part of the politicians and scientists believe that it would be easier to achieve this and in general to overcome the division between East and West in the new trans-regional co-operation in the northern areas of the Barents Euro-Arctic Region, established in 1993 as the northern outskirts of Europe, at least influenced by traditional debate on about government, history and identity [15, 2003]. The farther to the north, the closer becomes the East and West.

Unfortunately, these hopes have not yet been fully realized, and the Russian government during the last presidential term of Vladimir Putin (2000-2008 gg.) Was transferred to a certain stagnation in the relationship. As before, it was necessary to cooperate with the West, but at the same time and do not be afraid of confrontation. This was seen in the context of the desire to recreate Russia as a great power after the systemic crisis of the 1990s, which was seen by many Russians as a national humiliation. While the EU was trying to move away from the concept of nation state and to establish procedures in forming its policy based on the moving boundaries, the new Russia has sought to assert its full sovereignty. Perhaps the situation has changed from two centuries earlier. In the XVIII - XIX centuries Russia safely treated her frontirnym zones, and even welcomed the regime of open borders, Norway, on the contrary sought to clear and tight boundaries. Today, neighbors, bordering Russia (Finland and Norway), seems to aspire to a more transparent borders, while Russia continues to rely on the Westphalian doctrine.

But the picture is mixed. The period of presidency of Dmitry Medvedev has demonstrated greater openness and flexibility of Russia's approaches to resolving territorial issues. For example, in Norway has found broad support for reaching an agreement with Russia in April 2010 on the delimitation of the territories of the two countries in the Barents Sea, as negotiations were held for nearly forty years. Both countries have expressed a desire to move away from its principles. Norway defended the principle of dividing the equivalent marine areas between States and Russia advocated the principle of sectors. "General," the marine territory considered an area located between the boundaries formed by the application of these two quite different principles of maritime delimitation. Ratified by the current letter of intent comes from the fact that this "common area" shall be equivalent to the split between the parties2.

The agreement on the delimitation can be summarized as "an unexpected gift to Russian Tsar," on a par with the contract in 1826. But, apparently, Russia hopes to get something in return concessions to which they are cooperating with Norway in the forthcoming issue of oil and gas fields in the Barents Sea. Norwegian authorities have been extremely interested in establishing the exact maritime border with Russia and Russia rejected the proposed initiative on the establishment of a general control over the disputed area of the Barents Sea. Based on the above is interesting to note that the Norwegian government at the same time supports the use of crossborder actions on the ground that, in fact, may lead to the restoration of it a kind of "general constituencies."

The Norwegian government has invited Russia to create a Norwegian-Russian industrial and economic zone of cooperation in the border areas of both countries, the so-called "Pomeranian zone" whose activities will be especially associated with the advancing age of the oil in the Barents Sea. Russia reacted positively to this, but so far this idea has not gained general acceptance [1, 2009]. But perhaps, as a step in advance in this direction can be taken with effect from De- cember 1, 2008 significant easing of visa rules in the Norwegian-Russian border, as well as the abolition of restrictions on entry into the border town of Nikel and Polar. At present, negotiations on visa-free border passage for residents of Southern Varanger municipality (Norway) and Pechenga (Russia). This is an area which is very closely matches the former territory of siyt: Nei-den, Pasvik and Pechenga, i.e., the "general constituencies." Residents of this area in future will be able to cross the border, showing the identity of the border area residents, i.e., they can move freely within the territory, which until 1826 was a common territory. And if after this planned follow their own customs, economic and transit agreements, which, in accordance with the plan should be included in the Pomeranian area, then you can really talk about the restoration of the former common Norwegian-Russian possessions, but in the modern version.

Список литературы Norwegian-Russian Arctic frontier: from the whole districts to the Pomor region

- Urban Wråkber. Pomor Zone. A Cross-Border Initiative to Further Regional Development in Northern Norway and northwest Russia, Presentation at the IV Northern Social and Environmental Congress, 21−22 April 2009, Moscow.

- Hansen L. I. Interaction between Northern European Sub-Arctic Societies during the Middle Ages. Indigenous Peoples, Peasants and State Builders. In Rindal M. (ed.) Two Studies on the Middle Ages. KULTs Skriftserie No. 66. 1996. P. 31−95.

- Ruggie J. G. Territoriality and Beyond: Problematizing Modernity in International Relations. In: International Organization, Vol. 47, No. 1. 1992.

- Kratochwil F. Of Systems, Boundaries, and Territories: An Inquiry into the Formation of the State System. In: World Politics, Vol. 39, No. 1. 1986.

- Häkli J. Borders in the political geography of knowledge. In: Lars-Folke Landgren & Maunu Häyrynen (eds.), The Dividing line: borders and national peripheries. Helsinki, 1997.

- Lattimore O. Studies in Frontier History. Collected Papers 1928−1958. London, 1962. P. 534.

- Hansen L. I. I Russia − Norway. Physical and Symbolic Borders / Ed.: T. N. Jackson, J. P. Nielsen. Moscow, 2005. P. 40−61.

- Nielsen J. P. Some Reflections on the Norwegian-Russian Border and the Evolution of State Borders in General // Russia − Norway. Physical and Symbolic Borders / Ed.: T. N. Jackson, J. P. Nielsen. Moscow, 2005. P. 8.

- Johnsen O. A. Finmarkens politiske historie, aktmæssing fremstillet // Skrifter utgitt av Det norske videnskapsakademi i Oslo, II, Hist. fil. klasse. Kristiania, 1922. S. 231−236; Nikolskii V.N,. On The Russian - Norwegian borders. Arkhangelsk 1914. p. 4.

- Wikan S. Grensebygda Neiden. Møte mellom folkegrupper og kampen om ressursene. Svanvik, 1995. S. 39−46.

- Johnsen Loc. Cit. (Note 5), 218–219, the Archive of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire (AVPRI) F. 53/3. D. 661, D. 662.

- Medvedev S. A General Theory of Russian Space: A Gay Science and a Rigorous Science, in J. Smith (ed.) Beyond the Limits: The Concept of Space in Russian History and Culture. Suomen Historiallinen Seura, Helsinki. P. 18; Tolz Vera. Russia. Inventing the Nation Series. London, 2001. P. 159; Berdyaev N. The Origin of Russian Communism. London, 1937.

- Chulkov N.K. The history of bordering Russia with Norwegian. М., 1901. p. 154−155.

- Andresen A. States Demarcated-People Divided: the Skolts and the 1826 Border Treaty // Russia-Norway. Physical and Symbolic Borders / Ed.: T. N. Jackson, J. P. Nielsen. Moscow, 2005. PP. 80−104.

- Joenniemi Pertti & Sergounin Alexander. Russia and the EU’s Northern Dimension. Encounter or Clash of Civilisation? Nizhny Novgorod, 2003.