Обоснование чрезмерных расходов на ритуальные празднования

Автор: Ромашкина Г.Ф., Кибукевич В.С.

Журнал: Logos et Praxis @logos-et-praxis

Рубрика: Социология и социальные технологии

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.24, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

В статье авторы исследуют факторы, влияющие на готовность людей распределять значительные финансовые ресурсы ритуальных торжеств на примерах развитых и развивающихся стран. Цель исследования – выявить основы принятия экономических решений в различных культурах через отношение к финансированию ритуальных празднований (например, свадеб или похорон). Данные для анализа получены из базы Global Findex Database 2011, которая содержит около 300 показателей: наличие банковского счета, способы оплаты, наличие сбережений, степень закредитованности населения, финансовая устойчивость. Выборка охватывает 147 000 человек из 144 стран. Кроме того, проведен сравнительный анализ социологических данных. Показано, что в среднем не более 3 % респондентов сообщили о наличии кредита, взятого специально на свадьбу или похороны. Эта доля значительно варьируется в зависимости от региона. Респонденты из Азии и Африки демонстрируют значительно меньшую готовность брать кредиты на эти цели по сравнению с респондентами из Европы. Такие результаты противоречат уровням доступности кредитов и не могут быть полностью объяснены разницей в экономическом развитии или культурными особенностями. Готовность семей брать кредиты на ритуальные торжества сигнализирует о неэластичности расходов, связанных с ритуалами, по отношению к экономическим факторам. В странах, различающихся по уровню экономического развития, но связанных в прошлом как метрополия и колония, наблюдается схожесть в отношении к расходам на ритуальные мероприятия. Это подчеркивает главенствующую роль традиций. Также в исследовании выдвигается гипотеза о том, что по мере экономического развития общества традиционные модели поведения становятся более эластичными, то есть более чувствительными к экономическим ограничениям.

Ритуал, экономика, развитие, общество, культура, празднование

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149149475

IDR: 149149475 | УДК: 316.4 | DOI: 10.15688/lp.jvolsu.2025.2.11

Текст научной статьи Обоснование чрезмерных расходов на ритуальные празднования

DOI:

At first glance, the more developed a society, the less significance its members place on various aspects of ritual behavior. The results of studies presented in this paper suggest that contemporary residents of Northern Europe are much less inclined to spend beyond their means on various rituals, such as births, celebrations, or funerals. In contrast, some societies demonstrate a greater tendency to incur debt and take loans for traditional festivities [McDowell 2019].

Feasting is an intricate phenomenon with no singular, all-encompassing definition. Scholars such as Hayden and Mutschler provide varying definitions, emphasizing different facets of this complex practice. Hayden and Villeneuve define feasting as the sharing of special food, distinguished by its quality, preparation, or quantity, during a special event rather than as a routine occurrence. Their definition highlights the exceptional nature of the food and its association with specific occasions [Hayden, Villeneuve 2011; Mutschler (ed.) 2018].

In contrast, Nahum-Claudel expands the concept beyond eating, viewing feasts as multifaceted events involving a larger circle of people. These events include musical performances, formal speeches, prayer and sacrifice, political discussions, and even commercial transactions [Nahum-Claudel et al. 2016]. While both definitions acknowledge feasting as a social and cultural practice, Nahum-

Claudel emphasizes its diverse activities, whereas Hayden and Villeneuve focus on the extraordinary nature of the food itself.

This study examines individuals’ willingness to spend significant financial resources on celebrations, feasts, and rituals by analyzing examples from both developed and developing countries. The objective is to identify the foundations of economic choices based on the financing of weddings and funerals. Various occasions prompt individuals to host feasts, with some being recurrent and culturally significant. For instance, as noted by Sherry, Wallendorf and Arnold, Christmas and Thanksgiving are among the most prominent feasting occasions in American society [Sherry 1983; Wallendorf, Arnold 1991]. These events stand out due to their ritualized nature, where feasting plays a crucial role. Conversely, weddings and funerals mark pivotal life transitions, often involving substantial financial commitments.

The extraordinary financial investments required for weddings and funerals, often managed by one or two families, distinguish them. The statistics are compelling: the average cost of a wedding has surged to $30,000, and cumulative wedding- and funeral-related expenses contribute significantly to an annual retail sales total of $100 billion in the United States. Notably, wedding expenditures by couples have nearly doubled over the past 30 years [Otnes, Lowrey 1993]. By analyzing how people in different societies finance celebrations and feasts, this study aims to highlight cultural, social, and economic motivations. Understanding these motivations is crucial for determining whether such choices are rational. Moreover, the findings offer valuable insights for expanding methodologies in credit behavior research across diverse cultures [Capraro 2013].

The questions raised in this article are as follows. Why do individuals frequently exceed their annual income when hosting feasts and orchestrating lavish ceremonies? What motivates this spending pattern, and is there a discernible rational framework guiding it? Can we consider the expenses incurred in feasting as a potentially advantageous investment with a comparatively low level of risk?

Review of literature and main scientific approaches

This preoccupation with feasting is evident later in other cultures as well, including Mycenaean times, as highlighted in the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey , where feasting is depicted in various contexts such as the Poseidon feast at Pylos, palace feasts, settings for epic poetry recitations, and integral aspects of warrior and elite life [Sherratt 2004]. Similar descriptions of feasts are found in other classical literature, including Hippolochus’ account of a lavish wedding feast in Macedonia around 300 B.C., featuring an astonishing array of food, gifts, and entertainment. The proliferation of scenes and accounts of feasts continued during

Roman times, coinciding with the emergence of feasting manuals like that of Apicius [Donahue 2005].

Ibn Fadlan stands out as one of the earliest chroniclers of feasts in different cultures, providing a vivid account of a Viking chief’s funeral feast in A.D. 921, which included a debauched sacrifice of one of the chief’s young female slaves. Throughout medieval Europe, indigenous accounts of feasts persisted, including descriptions in Beowulf and various other graphic depictions [Pollington 2003]. These early records primarily offered descriptive narratives of events deemed significant by observers or participants. Feasting was often portrayed as an integral part of elite or palace culture, yet the underlying importance of these feasts and their broader societal roles remained unexplored during this “descriptive stage” of feasting studies. Moral judgments were scarce, with the exception of early Christian criticisms regarding pagan festivals and their associated feasting. It wasn’t until early colonial exploration that a growing interest emerged in understanding the underlying motivations and societal implications of hosting feasts.

In the realm of extravagant feasting, what may have seemed like an extravagant squandering of resources was often met with bewilderment by European administrators, whose primary mandate was to generate profits for their respective governments or companies. Lavish feasts were perceived as detrimental to revenue generation and were simply regarded as irrational and profligate conduct, seemingly entrenched in ‘primitive’ cultural traditions without clear justification.

This perspective has persisted across evolving industrial economies, irrespective of whether they operated under capitalist, socialist, or communist regimes [Hayden, Villeneuve 2011]. Consequently, traditional feasting practices were frequently prohibited by authorities (e.g., the Dutch, British Columbian, and Vietnamese governments) due to their perceived economic backwardness, often accompanied by arguments highlighting the idolatrous nature of such feasting customs.

Early ethnographic works are more descriptive regarding feasts. They highlighted the cosmological beliefs intertwined with feasting, often seen as rudiments of ancient society. For instance, Simoons underscored the significance of lavish feasts within Naga culture, portraying them as a mechanism to transfer life forces from prosperous hosts to monumental structures, accessible to village members to augment their own productivity [Simoons, Simoons 1968].

Reasoning behind feasting: the economic sociology approach

The role of feasts in societies can be assessed as a means of highlighting aspects of integration, solidarity, and social structuration. Solidarity is a fundamental concept in sociology. According to Émile Durkheim, solidarity transforms societies from a mere aggregation of individuals into cohesive structures [Durkheim 2005]. Durkheim distinguished between mechanical and organic solidarity: the former corresponds to traditional societies, while the latter is associated with social cohesion and social conflicts [Longhofer, Winchester (eds.) 2023].

The willingness to finance celebrations from the family budget provides insight into the social and cultural foundations of economic behavior. The prevailing theme that feasts played a role in fostering social cohesion became deeply ingrained and remains the most prevalent explanation for this practice. Feasting contributed to the creation of social unity, a view similarly upheld by Rosman and Rubel in their explanation of potlatches as originating from social structural needs [Rosman, Rubel 1971].

At a later point in time, Weiner proposed that funeral feasts, incorporating gift exchanges, played a crucial role in showcasing the strength of lineages among coastal New Guinea communities [Weiner 1988]. This strength, in turn, served as a pivotal factor in the negotiation of political influence both within and between these communities. Contemporary anthropologists and scholars assert more forcefully the role of feasts in fostering social cohesion. For example, Lapeсa et al. contend that the observed increase in rituals and feasts among the Ifugao people played a pivotal role in their successful resistance efforts. Their research has demonstrated that the success of this resistance was built upon the Ifugao’s capacity to consolidate their political and economic resources [Lapeсa, Acabado 2017].

This phenomenon unfolded in the Philippines during the Spanish conquest of the 17th and 18th centuries. Sophisticated techniques were employed, with the argument being that the social status of the Ifugao people was evaluated based on the number of feasts they sponsored, quantified publicly by the display of pig and carabao (water buffalo) skulls in Ifugao houses (bale). Therefore, the number of pig and carabao skulls mounted served as an indicator of social solidarity and cohesion in traditional societies [Lapeсa, Acabado, 2017].

Social interactions extend beyond mere solidarity. For individuals, it is essential to assess their position within the social hierarchy. One tool for evaluating this position is prestige. For example, Lapeсa and Acabado argue that in a prestigebased economy, such as that of the Ifugao, social status can be translated into the political sphere. They highlight that feasts serve multiple functions, noting that solidarity feasts, particularly the ma’ surubati (the celebration of a child’s first birthday), may also serve to enhance the child’s prestige, which could be advantageous in attracting desirable mates and forming beneficial marriage alliances [Lapeсa, Acabado 2017].

P. Sillitoe also emphasizes the self-interested motivations of feast organizers and influential individuals, although the precise nature of these motivations remains somewhat ambiguous. It remains unclear whether these actions are primarily motivated by the desire for prestige or by the pursuit of more tangible benefits, such as political influence, reproductive success, or personal security. Nonetheless, these studies draw attention to the potentially “exploitative” use of feasts by manipulative aggrandizers or powerful figures [Sillitoe 1978].

Another group of scholars posits that feasts function as signals in communication. These signals streamline communication among members of society, as illustrated by the idea that “patterns of action might signal particular hidden attributes, provide benefits to both signalers and observers, and meet the conditions for honest communication” [Bird, Smith 2005]. In this way, feasts can be understood as tools that enhance the efficiency of communication.

In contrast, Smith stresses that feasts consistently function as signals that influence the reputation of the hosting family. Smith argues that individuals assess the prestige and influence of the hosting family based on the quality of the feast. She suggests that “feasts demonstrate the family’s ability to endure anxiety and stress, as well as to manage the memory-making of events afterward.” Smith portrays feasts as high-stakes occasions where the weak may falter, while the strong accumulate greater power [Smith 2015]. She highlights the increasing pressure faced by hosts as the event approaches. These considerations are characteristic of more developed societies, where communication resources shape an individual’s place within the social hierarchy and become a source of power [Castells 2009, 50; Wunderlich et al. 2021]. J. S. Greer noted that celebrations in ancient times had a high social significance. Meaningful actions at the table required collective efforts, search, negotiation, and association [Greer 2022].

The culture of celebrations: format and purpose

As demonstrated earlier, holidays, feasts, and other communal events (including funerals) are an inseparable part of culture in all societies. Despite European colonists in newly conquered territories prohibiting feasts as irrational or sinful, they themselves organized lavish feasts to celebrate Christian holidays. This contradiction could be interpreted as a cultural or religious conflict. In Christian tradition, various holidays underscore the importance of feasting, with an emphasis on the communal sharing of food. Furthermore, Christian teachings encourage those who have abundance to share with their neighbors.

For instance, the New Testament states clearly: “If a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food, and one of you say unto them, ‘Depart in peace, be ye warmed and filled’; notwithstanding ye give them not those things which are needful to the body; what doth it profit?” (James 2:15–16). Consequently, feasting can be regarded as a religious component that has permeated culture. As G. Morrison emphasizes, the act of sharing food, especially with neighbors and those less fortunate, carries profound spiritual significance and serves as a representation of the kingdom of God [Morrison 2017; Ngqeza 2018].

Some scholars have proposed classifications of feasts based on their format and underlying purpose. For example, Adams identifies three main types of feasts: solidarity feasts, promotional feasts, and work feasts. Additionally, the author differentiates between potluck feasts and those organized by individuals or families. Other feasts, according to this classification, typically possess a hybrid nature [Adams 2004].

Solidarity feasts primarily aim to strengthen group cohesion and unity. These feasts often take the form of potlucks, where households, villages, or even entire subdistricts (groups of allied villages) come together to reinforce their social bonds. In contrast, promotional feasts are distinguished by their large attendance, abundant and prestigious food offerings (including costly items like rice and meat from domestic animals, typically provided by the hosting household), the display of prestige items, and a deliberate effort by the host to enhance their economic standing. Work feasts, on the other hand, are events where individuals contribute labor to a project lasting at least one day in exchange for food and beverages provided by the host [Adams 2004]. These feasts are common in agrarian societies, particularly in contexts requiring a substantial labor force, such as house construction or road building [Dietler, Herbich, Hayden 2001].

J. Sommerschuh concluded that changes in perceptions of the good towards more rational ones are manifested in the transition from feasting to accumulation [Sommerschuh 2022]. The growth of debt-driven consumption, as exemplified by the automotive market during the Covid-2019 pandemic, confirms that attributive consumption is supported by aggressive marketing, which today largely replaces traditional cultural values [Kurysheva, Vernikov 2024].

Data and methodology

The data for this analysis was sourced from the Global Findex Database 2011, which provides nearly 300 indicators on various financial topics, including account ownership, payment methods, savings, credit, and financial resilience. The sample size comprised 147,000 individuals from 144 countries across all regions of the world as defined by the World Bank. These surveys were conducted annually among adults worldwide, using a uniform methodology and nationally representative random samples. The database includes questions such as, “Do you currently have a loan for a funeral or wedding?” and “A credit card is like a debit card, but the money is not deducted from your account immediately. You receive credit to make payments or purchase items, and you can pay off the balance later. Do you have a credit card?”

In economies where landline telephone penetration is less than 80%, or where face-to-face interviewing is customary, surveys were conducted in person. The first stage of sampling involved identifying primary sampling units consisting of clusters of households, which were stratified by population size, geography, or both. Clustering was achieved through one or more stages of sampling. In cases where population information was available, sample selection was based on probabilities proportional to population size; otherwise, simple random sampling was used. Random route procedures were employed to select households, and interviewers made up to three attempts to survey the sampled households, unless an outright refusal occurred. If an interview could not be obtained from the initially selected household, a simple substitution method was used. Respondents were randomly selected within households using the Kish grid method.

In economies with landline telephone penetration over 80%, surveys were conducted by telephone through random digit dialing or using a nationally representative list of phone numbers. In countries with high mobile phone penetration, a dual sampling frame was employed. At least three attempts were made to reach a person in each household, distributed across different days and times of year. In the majority of economies, the sample size was 1,000 individuals.

The study employs historical and cultural analysis to explore the evolution of celebrations and their cultural aspects across different societies. It also utilizes comparative analysis of statistical data to identify patterns and differences in financial and social practices. Additionally, sociological observation data is analyzed to gain a deeper understanding of people’s behavior and perceptions within the context of cultural traditions.

The analysis of the obtained data included the classification of countries based on two criteria, each of which had three levels: low, medium, and high. The resulting groups of countries were characterized both qualitatively and quantitatively (See Table 1).

Results

On average, only 2.88% of the survey respondents reported having a loan specifically for a funeral or wedding. These loans serve as an important financial instrument for individuals in different regions, assisting in the management of significant expenses associated with major life events. The percentage of respondents who reported taking out loans for these purposes varies across regions, revealing insights into cultural practices and the economic landscape. In Asia, 4.07% of respondents indicated that they had used loans to finance weddings, a figure relatively low when compared to Africa. On the other hand, 5.75% of African respondents said they had taken out loans for either a wedding or funeral, indicating that loans are more commonplace in the area. The lowest rate of loans for weddings or funerals is reported from Europe at 2.03%. It is likely that regional differences such as cultural perceptions of borrowing, access to alternative financial options, and varying degrees of economic growth influence borrowing behavior across regions.

In terms of overall credit accessibility, Europe is uniquely positioned with a substantial level of financial inclusivity. While approximately 13.7% of respondents in Europe indicated credit card ownership, credit cards were virtually nonexistent in Asia at 4.17% or African countries at 5.75%. The comparatively lower percentages of credit card ownership in Asia and Africa suggest that the credit infrastructure and access to credit products are less developed in these regions. This may contribute to the greater borrowing in the form of loans for weddings and funerals in Asia and Africa. The greater range of credit product availability, such as credit cards in Europe, provides alternatives for financing major life events and may alleviate the need for loans for weddings and funerals. This illustrates broader trends in financial accessibility and credit culture across regions that can inform how individuals manage personal financial needs.

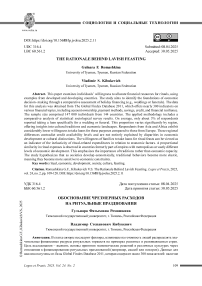

Paradoxically, some countries with the highest survey values for borrowing for funerals and weddings in the dataset are among the countries in which the data show low overall credit availability. For example, in Ghana (SubSaharan Africa), more than 16% of respondents borrowed towards a wedding or funeral, while in Afghanistan and Iraq, 28.4% and 11.9% of borrowers reported having done so, respectively (Fig. 1, 2). This suggests that there are high incidences of borrowing for life events (like weddings and funerals) generally, but such regions reported relatively low overall credit availability.

In this case study, Mauritania, Afghanistan, and Iraq are categorized as countries with low loan availability, with fewer than 10% of respondents reporting access to loans. The limited credit infrastructure suggests that many individuals turn to borrowing for important life events despite a financial system that does not actively promote credit development. This raises important questions about the role of informal lending and how cultural norms shape attitudes toward borrowing for significant personal events.

One possible explanation is the influence of Islamic finance, which prohibits interest-based

Fig. 1. Share of population has wedding/funeral debt: treemaps

Note. Made by author. Data was obrained from: [Global Findex 2025].

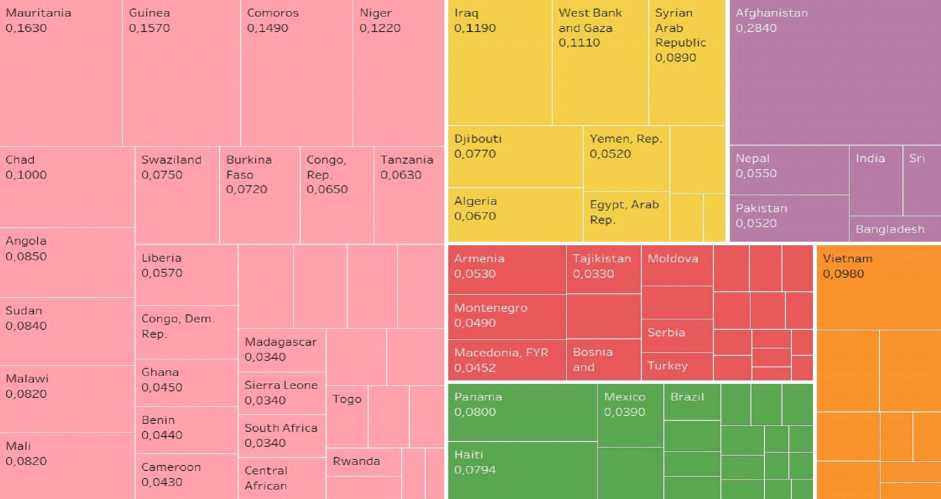

Share of population has wedding/funeral debt: treemaps (females only)

Fig. 2. Share of population has wedding/funeral debt: treemaps (females only) Note. Made by author. Data was obtained from: [The Little Data Book... web].

regionwb

-

■ East Asia & Pacific

-

■ Europe & Central Asia

-

■ Latin America &Carib._

-

■ Middle East & North A..

-

■ South Asia

-

■ Sub-Saharan Africa

lending but allows for various indirect forms of borrowing. Many Muslim-majority countries rely on conventional financial instruments, though these are often not widely used by the general population. Instead, lower-income individuals may turn to mutual Islamic insurance (takaful) or community-based financial assistance, which can help cover expenses for traditional ceremonies. Countries such as Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Bahrain, Kuwait, the UAE, Egypt, Oman, Jordan, and Turkey rank among the leaders in Islamic financial development. However, these financial tools are generally available only to local residents, whereas many of these nations have large populations of displaced people or temporary workers who lack economic and social security. At the same time, their need to finance weddings or funerals is similar to that of the general population. For instance, in Egypt, only 1.6% of respondents reported having credit cards – below the regional average – while approximately 4% reported taking on debt for weddings or funerals.

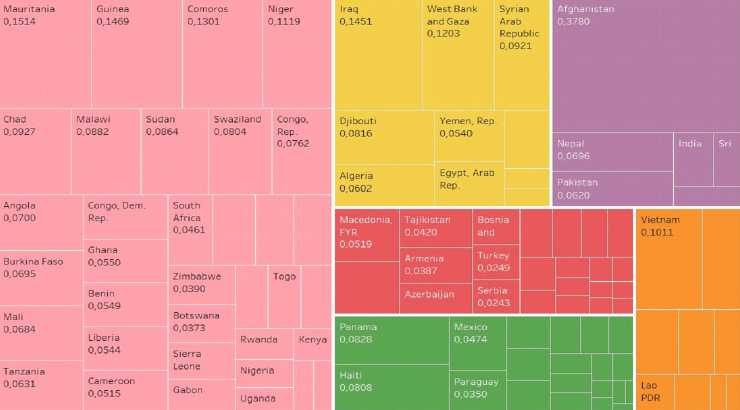

Looking at the broader picture, the top 15 countries in Islamic banking development show varying trends. In Malaysia and Jordan, access to credit reaches 14.4% and 5.4%, respectively, while the share of respondents who have borrowed for weddings or funerals is 2.9% and 1%. We grouped countries into three categories based on their proportions of loan borrowing and a measure of credit access to help better understand the relationship with financial systems and loan borrowing patterns. To measure “credit access,” we grouped the participating countries into three categories; of the sample, they indicated they received credit products (credit cards) (Table 1). We also classified countries by loan fraction (the % of respondents who borrowed or obtained debt to fund life’s events (weddings, funerals)) into three country categories (low, medium, high) (Table 1).

These classifications allowed us to analyze how different levels of credit availability intersect with borrowing behavior across regions, shedding light on the dynamics between financial systems and personal finance decisions (See Fig. 3).

The data from the Global Financial Inclusion also show that there is no stable direct relationship between the accessibility of credit and the share of the population having debt for funerals or weddings. Interestingly, in European countries, where credit accessibility was at its highest in 2011, 13.7%, compared to other regions of the world, the proportion of respondents reporting having debt for financing wedding or funeral ceremonies for close family members was the lowest, approximately 2%. For example, in countries such as Latvia, only 0.7% of respondents reported having debt for such purposes, while in Russia the proportion was around 0.95%. This suggests that, despite higher availability of credit products in Europe, the use of loans for such purposes remains relatively rare.

In contrast, in Sub-Saharan Africa, where credit accessibility is much lower, with an average of only 5.75% of respondents reporting having access to credit, the incidence of borrowing for weddings or funerals is considerably higher. For example, in Guinea, over 15% of respondents indicated they had taken out loans for these events, and in countries like Uganda and Senegal, the figures were also notable, around 6% and 4.2%, respectively. This highlights a significant regional disparity in the use of loans for life events, despite the difference in overall credit accessibility.

Conclusion

While the availability of credit and financial infrastructure varies by region, the data does not support a consistent relationship between these factors and the presence of debt for vital life

Table 1

Basis for classifying countries, % of respondents

|

Low (<10%) |

Medium (10% – 20%) |

High (>20%) |

|

|

Credit access |

"under-developed" category in financial systems with low access to formal credit |

moderate access to financial products and financial infrastructure |

developed financial systems and high access to financial products |

|

Loan fraction |

few respondents borrowed money for these events |

some respondents borrowed money |

many respondents borrowed money |

Note. Made by author.

events such as weddings and funerals. For example, in Europe and some Latin American countries, where access to credit cards is significantly higher, the percentage of the population using loans for weddings or funerals remains minimal (around 2%). In countries such as Latvia (20.3% of the population has access to credit products) and Uruguay (31.3% have access), the use of credit for these purposes is extremely low despite the presence of well-developed financial infrastructures, with less than 1% of the population reporting debt incurred for weddings or funerals. In contrast, in countries with lower credit accessibility, such as those in Africa, a significantly higher percentage of the population takes loans for weddings and funerals. For instance, in Mauritania, more than 16% of respondents report taking loans for these purposes, and in countries such as Afghanistan (28.4%) and Iraq (11.9%), the proportion of borrowers is also considerably higher. These figures suggest that in these countries, there is a stable social practice of taking loans for significant life events despite limited access to formal credit. These trends may be driven by cultural or religious norms that make loans for weddings and funerals socially acceptable, even in the absence of widespread formal credit availability.

A curious pattern emerges when comparing expenditures in countries with similar cultural backgrounds. Hayden discusses this in his article, where he examines the transformation of marriage rituals in Vietnamese communities from traditional pre-colonial practices to the modern communist framework [Hayden, Villeneuve 2011]. He notes that colonial history significantly altered wedding rituals. A similar trend can be observed in colonizing and colonized countries. For example, in Spain (the colonizing country), as well as in Chile and Mexico (colonized countries), wedding expenses are quite similar in absolute terms. In all three countries, people spend approximately 14 times the average monthly salary (after taxes) on weddings, though in relative terms, the amounts differ significantly. On average, wedding expenditures in Mexico and Chile are around $8,000–9,000 USD, while in Spain, this figure is about $24,000 USD.

Nonetheless, the overall pattern suggests that families’ willingness to take loans for ritual feasts can be seen as a manifestation of the inelasticity of expenditures associated with ritual

Fig. 3. Sankey diagram of the proportion of the population with wedding/funeral debt and the proportion of the population with credit card ownership

Note. Made by author. Data was obrained from: [Global Findex 2025].

behavior. This is more of a symptom than a problem, indicating that these expenditures are less responsive to economic factors. It is hypothesized that as societies develop economically, ritual behavior becomes more elastic, meaning it becomes more sensitive to economic constraints. For example, in economically developed countries such as Germany or France, wedding or funeral expenses are typically planned in accordance with available financial resources. This reflects a rational approach where economic variables play a significant role in decision-making. In contrast, in less economically developed countries such as Afghanistan or Mauritania, expenditures on rituals often exceed rational limits, leading to high levels of debt.

As for Islamic banking, it provides alternative forms of borrowing, although accessibility is still somewhat limited and still excludes groups such as migrant workers. Furthermore, the findings suggest that despite the overall low availability of formal credit in many Muslim-majority countries, borrowing for life events continues to be quite common. This may be due to the influence of informal lending networks and community-based financial assistance. Overall, the findings support the development of more equitable financial strategies towards inclusion that utilize financial service tools that extend past commercial banking in order to serve broader social and economic groups.

It is important to emphasize that the growing elasticity of ritual behavior does not imply a decline in the significance of rituals themselves or an increased role of the economy in decision-making. Rather, it reflects a higher level of rationality in decision-making. In economically developed countries, individuals are more likely to evaluate available alternatives and make decisions based on their financial capacities, thus reducing the debt burden. Irrational behavior in less developed societies may have different interpretations. For example, the large-scale conduct of rituals may be driven by the need to maintain social status or adhere to traditions, even if it results in financial difficulties. Thus, the differences in the elasticity of ritual behavior between developed and developing countries reflect not a decrease in the importance of rituals but differences in the approach to their economic support.

Future research directions

In the field of rituals and economic development, there is a promising avenue for further exploration. Future studies should prioritize examining the impact of feasting on community dynamics and political structures, as well as the benefits it provides to both hosts and participants. It is also essential to delve into the intricate relationships between feasts and productive social units [Lapeсa, Acabado 2017; Smith 2015]. Another critical area of investigation is understanding the motivations behind the complete redistribution of a deceased individual’s wealth during specific funeral feasts. Researchers should rigorously challenge various assumptions about the tangible manifestations of feasting at household, kinship, and community levels, including practices such as material borrowing and the final disposition of surplus gift food [Hayden, Villeneuve 2011].

An intriguing area for future research in economic sociology involves exploring the anticipated interest rates associated with loans and gifts and understanding the factors contributing to their fluctuations. This includes scenarios where straightforward reciprocity is sufficient for some individuals, while others demand double or greater returns. Researchers should examine the varying contributions of individual households, including those who neither host nor participate in feasts. It is also crucial to analyze the consequences that arise when the expected returns from feasting are not met [Adams 2004].