Offerings of Hunnic-type artifacts in stone enclosures at Altynkazgan, the Eastern Caspian region

Автор: Astafyev A.E., Bogdanov E.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145368

IDR: 145145368 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.068-078

Текст обзорной статьи Offerings of Hunnic-type artifacts in stone enclosures at Altynkazgan, the Eastern Caspian region

The golden guard thee from the sky, The silvern guard thee from the air, The iron guard thee from the earth! This man hath reached the forts of Gods.

Atharvaveda , V, 28: 9*

Description of monuments and finds

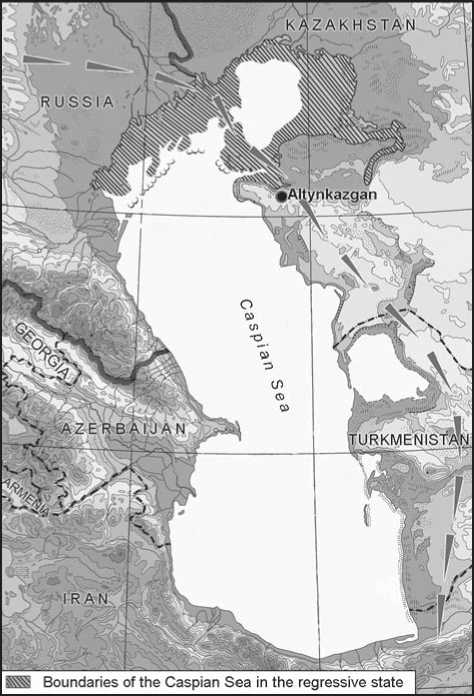

The Altynkazgan site is located on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1) and represents a fairly compact cluster of various stone structures, including burial mounds, stonework in the form of individual walls, horseshoe-shaped structures, and three types

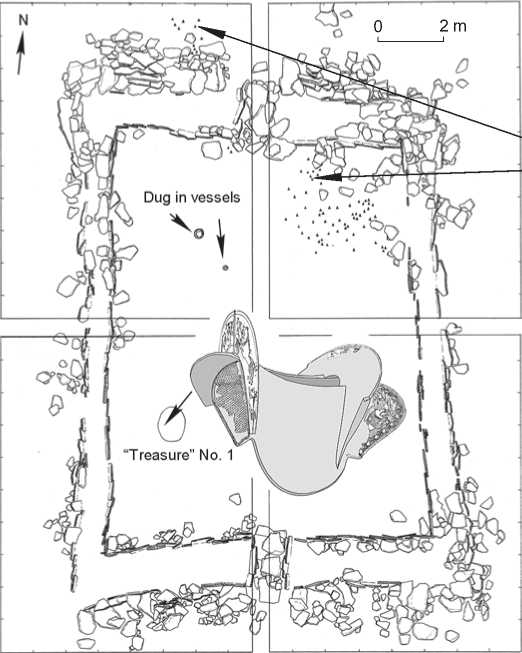

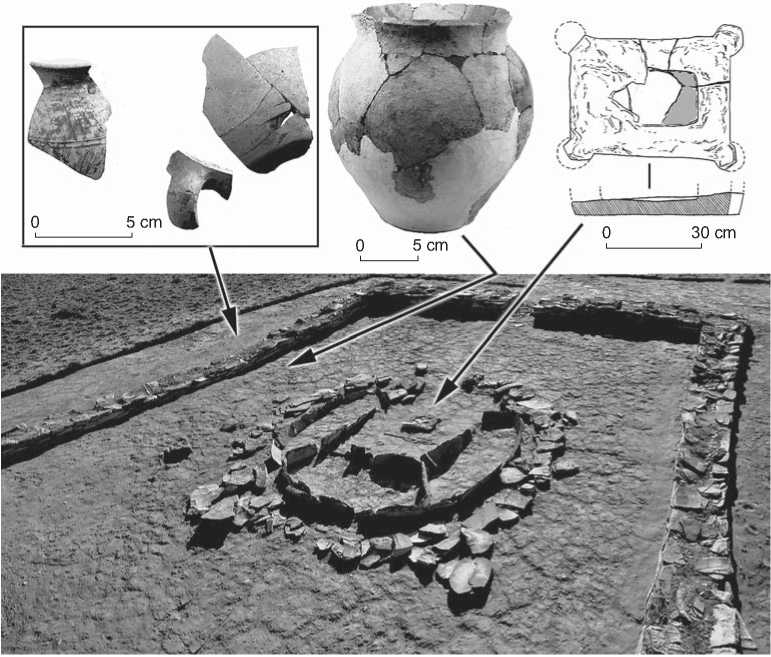

of enclosures. In 2014–2016, five enclosures, three horseshoe structures with “boxes” of dug-in slabs, and stonework in the form of a wall were investigated. Pottery fragments (and intact forms) were found on the territory of all structures, and a calcined spot was discovered in a “box”. The way the stones were arranged makes it possible to assume, with a high degree

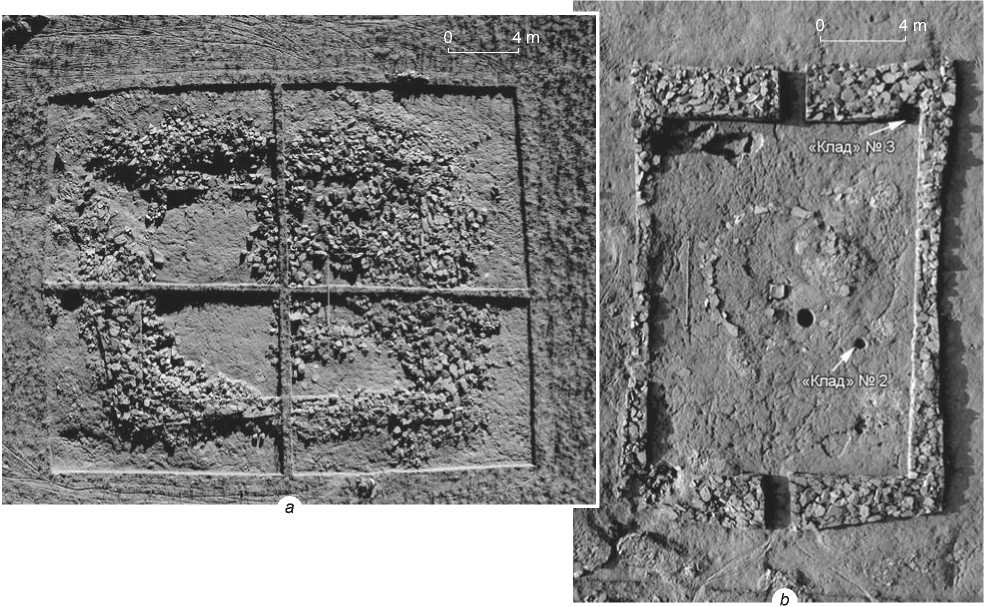

Another explored stone enclosure (structure No. 168) was also rectangular in plan view (21 × 14 m) and was oriented to the cardinal points. Only the walls were built of flagstone in horizontal stonework. Their width was 0.8–1.2 m. The height of the preserved part of the enclosure reached 0.7 m from the surface level. Passages 0.9 m wide, filled with piled rock, were in the northern and southern walls. The walls of the enclosure have partially survived: only the lower layer (foundation) has remained from the eastern and western walls. Stones from the walls lay nearby forming massive embankments: someone must have specially disassembled the stonework and placed the stones nearby (Fig. 3, a ). The southwestern corner of the enclosure was completely destroyed by a looters’ pit. In the center of the interior space, the remains of an altar

Fig. 1 . Location of the Altynkazgan site and the map of the Hunnic raids to Iran in the first half of the 5th century.

0 5 cm

Dug in vessels

2 m

‘Treasure" No. 1

Fig. 2 . Plan of the stone enclosure (structure No. 15) and pottery from it.

а

*» к

b

Fig. 3 . View of the stone enclosure (structure No. 168) from above after clearing ( a ) and after finishing the works ( b ). Arrows indicate the location of the “treasures”.

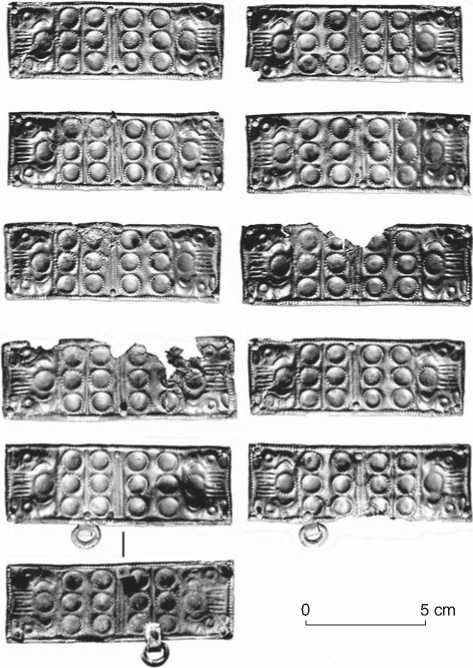

Fig. 4 . Parts of the belt (“treasure” No. 2) from structure No. 168.

in the form of a semicircle of flat stone slabs was found (Fig. 3, b ). The altar was made of a single chalk block (60.0 × 61.5 × 12.0 cm) and lay in a small depression opposite a passage leading to the middle of the semicircle. The altar was damaged in the ancient times and was partially covered by slabs (after performance of a ritual?)*.

Outlines of two pits were discovered in the eastern sector of the interior space of the enclosure. One of the pits had traces of recent penetration of looters and contained the remains of a belt (“treasure” No. 2; Fig. 3, b ) including seven gilded silver plates (three more were extracted earlier by “treasure hunters”) with punch embossing and griffin heads in the corners, a gilded decorative “shield on tongue” buckle with amber inserts, and a buckle shield containing the same ornamental motif (Fig. 4). The plates

5 cm

■У^

5 cm

5 cm 9

5 cm

5 cm

12 0

0 5 cm

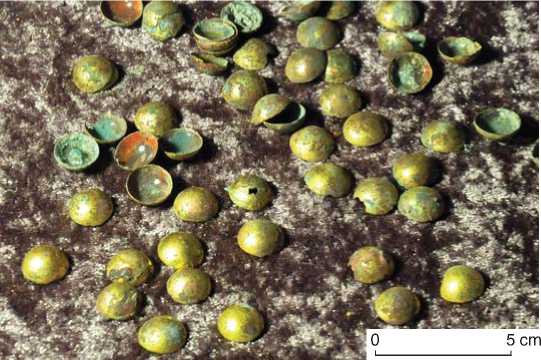

Fig. 5 . Parts of the horse bridle (“treasure” No. 3) from structure No. 168.

1 – copper noise-producing pendants; 2 – bronze pendant; 3 – iron bits with gilded silver psalia; 4 – harness plates (copper, silver, gilding); 5–8 – strap distributors (copper, silver, gilding, paste inserts); 9 – fragment of fabric; 10– 14 – masks – horse bridle adornments (copper, silver, gilding); 15–17 – buckles of harness straps (copper, silver, gilding); 18 – plate with inlay (copper, silver, gilding);

19 , 20 – pendants (copper, silver, gilding).

Fig. 6 . Plaques (copper, gilding) from “treasure” No. 3.

Fig. 7 . View of stone enclosure (structure No. 63) from the top after finishing the works.

were attached with copper rivets to a leather belt, which has not survived. Two plates had decorative pendant rings. Nothing was found in the other pit; possibly, a pot might have been originally located there.

“Treasure” No. 3 was found under the enclosure wall near the northeastern corner (see Fig. 3, b). The upper part of the stonework was displaced by modern looters, but the lower slabs, which remained in situ, indicate that initially all elements of a horse bridle were placed under the wall of the enclosure into a small pit. These elements included: noise-producing pendants of the same type in the form of pyramidal bells rolled from a thin copper sheet (47 objects); a large solid cast bell also of a pyramidal shape; iron ringed bits with silver psalia; decorative onlaid thin plates (20 objects), made of copper and covered with silver foil with gilding (two truncated) with complete ornamental décor made by punch embossing; dispensers of bridle straps (4 objects, all of the same size), encrusted with amber inserts and almandine (?) in the center (one retained a fragment of red-dyed fabric); masks of the same type (5 objects, one in small fragments)—thin copper plates covered by silver foil with gilding and decorated by anthropomorphic relief image using the method of punch embossing; belt buckles with shields of the heraldic type encrusted with amber, a hollow frame made of silver plate with gilding (4 objects, all of the same type and size); an onlaid rectangular plate with similar ornately shaped cloisonné inlay (with the inserts of amber (?), partitions with gilding); pendants (2 objects) of thin copper plates covered by silver foil with gilding (Fig. 5); semispherical hollow plaques (152 objects) with a diameter of 7–9 mm (Fig. 6); and small paste beads of white color (12 objects).

The third explored stone enclosure (structure No. 63) was located on a small hill apart from the main complex of structures at the site. It was rectangular in plan view (15 × 11 m); the longitudinal axis was oriented along the E–W line. The walls were built in the technique of double-row slab stonework with sand and stone rubble filling (Fig. 7). Passages 0.9 m wide, (subsequently?) filled with stone, were in the eastern and western walls. In the center of the enclosure, a horseshoe-shaped altar structure, made of vertically installed slabs with partial filling of soil and tiled pavement (Fig. 8), was unearthed. This altar structure was divided by radial partitions into three sections. In the center of the structure, a severely cracked base of the “sacrificial” altar made of chalk was found—a slab of quadrangular shape measuring 50 × 37 cm, 4–7 cm thick, with poorly preserved rounded protrusions (9 cm in diameter) at the corners.

There were no traces of pits inside the enclosure. Over a dozen fragments of gray-clay pottery, both hand-molded and wheel-turned, were found near the walls (on the outer and inner sides), at the level of the ancient surface (Fig. 8).

Interpretation of the materials

A large number of various objects, including those made of precious metals, indicates the great importance of ritual actions in the stone structures of Altynkazgan. Stratigraphic observations confirm that the “treasures” inside the enclosures were placed some time after their construction. It is possible that these phenomena are not directly related to each other. At present, it is quite difficult to accurately determine the time when the enclosures were built, since the lack of bones and charcoal makes it impossible to date the objects using the methods of natural sciences. At the beginning of our study, we came to the conclusion that the planigraphy and forms of stone structures indicate the Late Sarmatian circle of monuments. This made it possible to associate the enclosures with “places of ritual meals” (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2015: 79–80). However, it was alarming that Altynkazgan differed from other similar sites of the region by its size and number of objects concentrated on a relatively small area. All other known enclosures in Mangyshlak (Ustyurt), and in Turkmenistan, are

Fig. 8 . Altar structure in the center of the stone enclosure (structure No. 63) and finds.

isolated, and their walls were built in a rough manner from various types of stone or earth. The presence of any additional structures or altars in them was not visually confirmed. If we take into account ritual burials of the high-status objects belonging to the warrior riders on the area of the Altynkazgan enclosures, we may speak about a phenomenon of a completely different level than just “places of ritual meals”. It is now difficult to say whether such “treasures” were in every enclosure (structure), but in almost all cases we observe traces of destruction in the walls of the stone structures, which occurred in ancient times. Probably, people knew about the presence of gold and silver jewelry under the stones, which might have resulted in mass destruction of such structures by looters. The very name of Altynkazgan (‘the place where gold was dug’, in the Kazakh language) is clearly of Turkic origin. According to our observations, the process of looting the site could have started in the 7th century AD. The dating of the saddle and elements of the saddle set from “treasure” No. 1 has already been established (Ibid.: 82–83). Moreover, the “pictorial text” on the Altynkazgan plates (Ibid.: Fig. 5–9) without any doubts fully corresponds to the “kingly theme”, and the owner of the saddle (or the “orderer” of the ritual) had a very high status in the nomadic military hierarchy.

(Shaunaka), 2005: 519). “In the incantation for a long life, out of the gods, people primarily turn to the god of fire Agni, who is considered directly connected with the life force. Gold, pearls, wood of certain species (putudru), and sacred belt are used as amulets” (Atkharvaveda, 1989: 34–35).

-

1. By the direction of that God we journey, he will seek means to save and he will free us; The God who hath engirt us with this Girdle, he who hath fastened it, and made us ready.

-

5. Thou whom primeval Rishis girt about them, they who made the world,

As such do thou encircle me, O Girdle, for long days of life.

Atharvaveda , VI, 133: 1, 5

As A.I. Ivanchik noted, “In the Indo-Iranian tradition, not only the cup, but also the belt were associated with priesthood” (2001: 337). There are many proofs of that. For example, when Kartir was approved as the high priest under Bahram I in the Sassanid Empire, he was granted the investiture symbols of the title—a headdress of specific form and a belt (Lukonin, 1969: 105). “A special belt ( kostik ) played an important role in the Zoroastrian rituals: believers had to wear it starting from a certain age” (Ivanchik, 2001: 337). Precisely such a belt allowed the Zoroastrian mythical king to defeat Ahriman and the

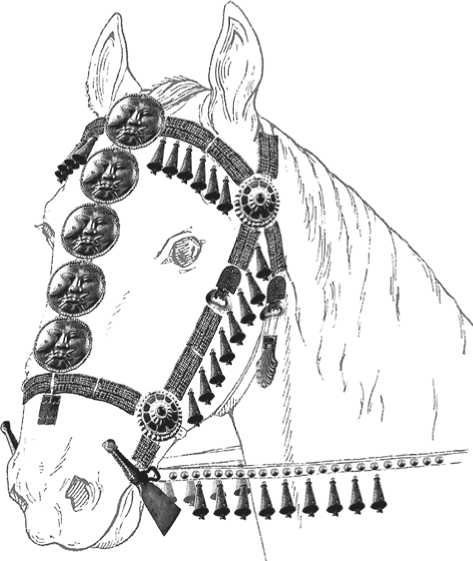

Fig. 9 . Reconstruction of the ceremonial horse bridle (“treasure” No. 3) from structure No. 168.

demons (Ibid.: 338). All this makes it possible to interpret the Altynkazgan “treasure” No. 2 in terms of a ritual that in some way was associated with the “kingly theme”. Within the ritual, the belt acted as a symbol of power and high social status. The Altynkazgan “treasure” No. 3 (a luxurious bridle set of gilded silver and copper objects, including elements with ornamental décor and inlay (Fig. 9)) should also be considered from the point of view of the ritual.

As we have already mentioned above, we cannot say when exactly the cultic complex at Altynkazgan was erected from the stone enclosures, but we can suggest who performed ritual burials of things, and for what purpose. First, we should try to outline the circle of parallels to the objects from “treasures” No. 2 and 3 (this has already been done for the elements of the Altynkazgan saddle (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2015: 80)). Belt buckles with prongs shaped like elephant trunks and shields with cloisonné inlay (see Fig. 5, 15 , 16 ) are commonly found among the Hunnic antiquities of the second half of the 5th–first third of the 6th century. Similar objects have been found in grave VIII in Novogrigorievka and in the burials near Birsk and Ufa (Ambroz, 1989: fig. 7, 1 ; 28, 2 ; 34, 13–15 ; 35, 30–33 ). We should note here not only technological and structural elements (inlay), but also stylistic correspondences (the cut border on the shield as an imitation of the rope ornamental décor). Thus, for example, buckle shields with similar typological and stylistic features have been found in the destroyed burial near the village of Fedorovka (Volga region) (Zasetskaya, 1994: Pl. 34, 15 ). Speaking more specifically about the design of the shields on the Altynkazgan buckles, a horse phalar from random finds in Europe (stored in the Museum of Stuttgart) (Quast, 2007: Abb. 1) is decorated with the same “bean-shaped” pattern with inserts. The same pattern also appears on the adornments from the Kerch catacomb burials (Spitsyn, 1905: Fig. 28) and on the elements of harness from the Tsebelda fortress (Abkhazia) (Voronov, Yushin, 1973: Fig. 15, 6–12 , 16–18 , 21 , 22 ). Plates (the copper base covered with gold leaf) with stamped decoration in the form of circles imitating round slots for inserts and a border with notches were found in burial 957 of the Ust-Alma necropolis (Crimea) (Puzdrovsky, 2010: Fig. 3, 4–7 ; 4, 3–7 ), in burials VIII and IX at Novogrigoryevka, and in the burial on the territory of the “Voskhod” collective farm, near Pokrovsk, in the Lower Volga region (Ambroz, 1989: Fig. 7, 7 ; 8, 4 , 19 ; 15, 13 ). They also appear among random finds from the North Caucasus (Ibid.: Fig. 8, 11 ), and among the materials from the Brut-1 burial ground (mound 9) (Gabuev, 2014: Fig. 64, 7 ).

The circle of parallels to the Altynkazgan harness plates with a rope-like border and stamped decoration in the form of grain-shaped figures (see Fig. 5, 4) can also be confined to the territory of the Black Sea region, Volga region, and Southern Urals. Twelve such stamped bronze plates, covered with gold leaf, were found in burial 2, mound 4, near the village of Vladimirskoye; six plates were found in burial VII of Novogrigoryevka, and one in mound 3 near the village of Shipovo (Zasetskaya, 1994: Pl. 6, 9; 35, 7, 8; 40, 4). Notably, in the first two cases, in addition to these plates, the horse harness included round masks (3 objects in each case) with anthropomorphic representations (Ibid.: Pl. 6, 3, 4; 35, 9). They are extremely similar to the Altynkazgan masks in terms of technological and iconographic features, although the latter are certainly more elaborate and have a “demonic” appearance (see Fig. 5, 10). A.K. Ambroz believed that “the appearance of masks on the harness of nomads can be associated with the influence of Rome or Iran” (1989: 73)*.

It is important for the topic of our article that almost all objects from the Altynskazgan “treasures” fit into the typological pattern of Hunnic antiquities of precisely the second half of the 5th–first third of the 6th century. Further search for parallels and analysis of funeral inventory from the sites contemporaneous with Altynkazgan cannot bring us closer to answering the questions posed above, but the written evidence may be of some assistance. The main sources of information about the events of the time which interests us are the records of Priscus of Panium and the writings of the historians Jordanes and Yeghishe. This evidence in various interpretations has appeared many times in the modern historical (archaeological) literature (see, e.g., (Gadlo, 1979: 49–57; Kazansky, Mastykova, 2009: 123–125; Gabuev, 2014: 82–86; and others)). We are primarily interested in the information about the expedition of the Huns Basik and Kursik from the steppes of Scythia to the Median region (Iran), which, as A.V. Gadlo believed, occurred in about the 420s–430s (1979: 49–50), “According to their stories, they went through the steppe region, crossed some lake which Romulus believed to be Maeotis, and after fifteen days they crossed some mountains and entered Media…” (Skazaniya…, 1860: 62–63). Gadlo, and subsequently M.M. Kazansky and A.V. Mastykova, also believed that the Huns passed the Sea of Azov in the lower reaches of the Don, and entered Iran-controlled Georgia through the Darial Gorge. After that, they returned to the steppes along the western coast of the Caspian Sea, through the territory of present-day Baku (Gadlo, 1979: 49–50; Kazansky, Mastykova, 2009: 123–124). If we assume that the Huns did indeed cross the Sea of Azov (which in itself is very strange: why not go around via the northern steppes?), they would inevitably and in an unhindered manner pass the borders and urban centers of the Bosporan Kingdom, Colchis, Iberia, and Armenia, crossing “some mountains”— the Armenian Highlands or the Lesser Caucasus. Only then could they enter Media, which at that time occupied the present-day territories of Azerbaijan, Armenia, Eastern Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan. In another version, the horsemen would have had to overcome the ridges of the Greater Caucasus and again pass the Lesser Caucasus. In any case, the Huns had to cross over not simply mountains, but a whole mountainous country. These hypotheses seem unlikely. Trying to comprehend the ways how the complex of metal objects, uniquely comparable to the Hunnic antiquities of the Lower Volga region, the North Caucasus, and the Black Sea region, could have reached the geographically isolated (by the Caspian Sea and the waterless Ustyurt Plateau) territory of the Mangyshlak Peninsula, we would like to consider another version of Basik’s and Kursik’s route.

Some scholars (Gumilev, 1966: 63–64, 182; Galkin, 1978; Astafyev, 2014: 238–239) have suggested that a vast land bridge between the northern and eastern coasts during the regressive state of the Caspian Sea existed precisely in the area of the Mangyshlak Peninsula. Specific features of the seabed in the Northern Caspian are such that even at a sea level of about 30 m, a huge freshwater basin was formed on the place of the Ural furrow, which was fed by the rivers Akhtuba, Ural, and Emba, and was separated from the sea by a wide, up to 50 km, isthmus with channels. At that time, the delta of the Volga River moved 70–80 km to the south. Given favorable climatic conditions, the “bridge” could successfully “unite” the peoples of Europe and Asia (see Fig. 1). According to geomorphological studies, such events might have occurred several times in the Holocene history of the Caspian Sea (Varushchenko S.I., Varushchenko A.N., Klige, 1987: 62–75, tab. 7, fig. 13; Gumilev, 1980: 36, fig. 2). Scholars agree that the level of the Caspian Sea dropped from the second half of the 5th century, reaching the minimum sufficient for the existence of an isthmus or shoal during wind surges in the 6th century and making it possible to wade through (Zakarin, Balakay, Dedova, 2006: 92). This is the probable localization of “some lake” and a logical explanation for the crossing of the Hunnic detachment through this “lake” according to the version of Priscus of Panium. Beyond the lake, the Huns moved for 15 more days and passed through “some mountains”. The unobstructed path for the horsemen along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea through the deserts of Mangyshlak and Turkmenistan to the foothills of the Iranian Alborz is slightly more than 1000 km, which, with a 15-day route, would correspond to a passage of about 70 km per day (this is far from the limit of one day’s passage for the steppe breeds of horses (Dolbe, 2012)).

The arid areas of Mangyshlak and Turkmenistan might have become a corridor for rapid advance of the Huns to the south. And finally, “some mountains” on this route would be the foothills of the South Caspian Alborz Ridge. In this way, the Hunnic detachments could have reached the territory of present-day Iran.

Such an interpretation of the expedition of Basik and Kursik is certainly controversial, and we definitely do not regard the appearance of the Altynkazgan antiquities as a direct consequence of the passage by the Huns through Mangyshlak. The nature of the destruction of the complex by ancient looters, as well as the richness and variety of the metal objects of the 5th century, which have been found, indicate their longer existence rather than a short stay of the Huns in Mangyshlak. The idea of the northeastern Caspian bridge is more global and implies periodically stable ethnic and cultural contacts between the population of the semi-desert zones of the Northern Caspian Sea region and the Mangyshlak Peninsula. We should not forget that Hunnic raids to Iran (Media) in fact constituted the migration of multiethnic tribal associations, even if under the leadership of the “kingly Huns”. Rituals at the Altynkazgan cultic complex might have been performed by the Huns of Rugila–Attila or by the Iranian-speaking groups of the Ciscaucasia (the Akatziri?), who, according to Gadlo, were the descendants of the Alano-Sarmatian population of the steppe (1979: 52–53). Completely different ritual actions were typical of the groups of Iranian-speaking (Turkic-speaking?) origin in the Ural-Kazakh steppes, which may have wintered in the sands of the Muyunkum Desert and in the foothills of Karatau, and would migrate for the summer to Central Kazakhstan and the Southern Trans-Ural region, up to the edge of the forest-steppe zone of the Urals (Tairov, 1993: 23). According to I.E. Lyubchansky, precisely these groups, “subjected in the 5th century to the vassal dependence of the powerful Hephthalite-Kidarite state”, might have left the burial mounds with “whiskers” (1996: 307). We do not intend to discuss the burials or ritual complexes associated with fire (cremation), such as Novofilippovka and Solonchanka I in detail (see (Kazansky, Mastykova, 2009: 118)), although objects of Hunnic appearance have also been found at these sites. As A.V. Komar argued, “burial mounds with ‘hearth spots’ of the Saratov Volga region represent the final chronological stage in the development of the ritual complexes of the Hunnic tribes of Eastern Europe in the late 5th to first third of the 6th century, while the burial mounds with ‘whiskers’ of the Ural-Kazakh steppes demonstrate the fully formed appearance of their structures already in the second quarter of the 5th century” (2013: 105).

Relying on Jordanes’ report on the funeral of Attila and the publications of the materials from the Volga region, northern Black Sea area, and Eastern Europe, Komar convincingly substantiated the hypothesis concerning the existence of a spatial division of the burial place of the body and the place of the sacrificial offerings among the Hunnic tribes (Ibid.: 103). It is true that most European and Russian scholars link these offerings in some way to commemorative (funerary) rites. However, for example, in the Hungarian complex at Pannonhalma, the objects had no traces of fire: in a shallow (up to 1 m) pit, two swords (with straps for wearing?) and two bridle sets were found (Tomka, 1986: 423–425), while in other cases, the high-status objects of warrior riders were subjected to a “purifying” fire and/or were intentionally damaged, as was the case, for example, in Makartet (the Dnieper basin) (for more details see (Komar, 2013: 91–103)). Yet, neither in Pannonhalma nor in Makartet have any burials been discovered near the “ritual burials” of artifacts. This fact can be explained by the concealed nature (without a structure above the ground) of most of the currently known burials belonging to noble Huns. However, this does not mean that all ritual actions discovered by archaeologists should necessarily have a commemorative purpose and be accompanied by a burial.

The analysis of objects from funerary and commemoration monuments allowed Komar to draw a conclusion about the existence of “a single ethno-cultural space in the steppes from the Danube to the Southern Urals in the first half of the 5th century” (Ibid.: 100). Although stone enclosures that manifest pronounced horseman’s cults have been found in the Caspian region (Altynkazgan), ritual burials of objects associated with warrior riders came to the fore in the northern Black Sea area and Eastern Europe, while burial mounds with “hearth stains” and with “whiskers” prevailed in the Volga and Ural-Kazakh steppes. According to Komar, burial mounds with “whiskers” are “without military attributes, with one or several vessels belonging to the usual commemoration ritual” (Ibid.: 104). However, the vessels that have been found in the Altynkazgan enclosures (dug in and/or broken) and the traces of calcination near the altar structures rather indicate the performance of the pre-Zoroastrian rituals dedicated to water (haoma) and fire. Referring to J. Gonda (1974: 49), Litvinsky very interestingly interpreted the ceremonies described in the Atharvaveda and related to the king and golden vessel, “This is reminiscent of the following ritual prescription that a person who was long absent and deemed to be dead, after his return, had to perform a ritual of rebirth in a gold (or clay) vessel filled with melted butter and water” (1982: 42). The burial of gold objects of high status fits quite well the general picture of the ritual:

Home-woven raiment let him give, and gold as guerdon to the priests. So he obtains completely all celestial and terrestrial worlds.

Atharvaveda , IX, 5: 14

Therefore, the construction of complex and laborintensive stone structures, along with burying large vessels, can hardly be called “a usual commemoration ritual”*.

Conclusions

-

1. Burials of high-status objects of warrior riders in the stone enclosures of Altynkazgan could have been made after the Hunnic raids to Iran (Media) in the second half of the 5th to the first third of the 6th century, when there was a land crossing between the northern and eastern coasts of the Caspian Sea due to its regressive state with access to the Mangyshlak Peninsula, near the Altynkazgan site.

-

2. Ritual burials of the “golden” belt, ceremonial saddle, and high-status adornments of a horse bridle were made in honor of the eminent representatives of the nomadic communities belonging to the Iranian-speaking group (of the Ciscaucasus?). The facts prove the existence of already advanced cults associated with the sacrificial offering of artifacts, which were prestigious for warrior riders, and the conducting of pre-Zoroastrian rituals devoted to water and fire in the Aral-Caspian region.

-

3. The similarity between the object complexes of the 5th–6th centuries from the funerary and commemoration monuments of Eastern Europe, northern Black Sea area, Volga region, and Caspian Sea area testifies not to a “single ethnic and cultural space”, but to a certain “fashion” for things made of precious metals with inlays among the nomad elite. This “fashion” probably emerged as a result of active contacts of the nomads with Sasanian Iran and the state entities under its influence.

Acknowledgement

This study was performed in accordance with the research plan under the Program XII.186.2.1, Project No. 0329-2018-0003.