Okunev statues at mount Uitag, Khakassia

Автор: Bogdanov E.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Minusinsk steppe, Okunev art, mythology, statues, steles, masks

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146815

IDR: 145146815 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.4.049-057

Текст статьи Okunev statues at mount Uitag, Khakassia

Monumental Okunev stele-like statues came to the notice of researchers of the Minusinsk steppe in the 18th century. They described and made drawings of over ten stones of “unclear chronological and cultural affiliation” (for more details on the initial stages of studying the sculptures, see (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 38–39)). By the 1930s (Gryaznov, Schneider, 1929: 63), over a hundred such sculptures were known, and by the beginning of the 21st century, over five hundred stone steles and slabs with images had been found (Esin, 2009: 29). Most of these objects of ancient art

are in museums; a smaller part has been left on the natural terrain of Khakassia, protected by the state and worshiped by the local population. A significant number of sculptures are known only from the field sketches by D.G. Messerschmidt, F.I. Strahlenberg, P.S. Pallas, and J.R. Aspelin (Messerschmidt, 1962; Aspelin, 1931). The corpus of data on stone steles with anthropomorphic imagery has been constantly growing due to archaeological excavations caused by economic development of the territories. The article introduces two new pieces of monumental art, which were discovered during rescue archaeological works in the Askizsky District of the Republic of Khakassia in 2021, and provides their historical interpretation.

Archaeological context of the slabs and their description

Both steles of the Okunev period were parts of enclosures of the Tagar burial mounds at the Skalnaya-6 and Uitag-3 sites. These complexes constitute one huge burial field on the slightly hilly part of the left-bank valley of the Abakan River, to the northwest of the peaks of Mount Uitag. The Askizsky District (especially in the basins of the Kamyshta and Uibat Rivers with their tributaries) is traditionally considered to be a “classic location of stone babas ” (Gryaznov, Schneider, 1929: 63; Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 37), since this microdistrict is rich in sites of the Afanasyevo and Okunev cultures.

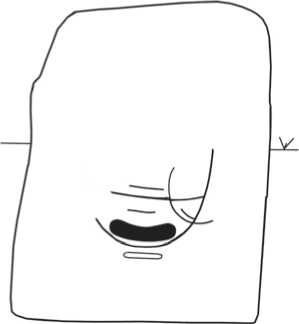

The stele with the image of an anthropomorphic mask at Skalnaya-6 is a Devonian sandstone slab adjacent to the southern wall of the enclosure (Fig. 1). This “ten-stone burial mound” is a classic example of an elite burial complex of the Saragash period (for more details, see (Bogdanov, Timoshchenko, Ivanova, 2021: 880–881)). All slabs of the enclosure were 1 m above the ancient surface and were set to form one straight line on the upper edge. Ancient builders took into account the pressure of the large mass of earth in the center of the mound, so nearly every element of the enclosure was reinforced on the outer side with a powerful buttress—a slab dug on its edge. The top of the stone (2.3 m high, 1.5 × 0.3 m in size), which had the mask on its broad side, was rounded (Fig. 2). Since the stone adjacent to the wall was set in the enclosure soundly and in a structurally correct manner (with its “face” outward), it may be assumed that builders of the Tagar burial mound treated it also “consciously”, and possibly with reverence. According to N.Y. Kuzmin, such an attitude suggests preservation of religious traditions of the earlier periods among the Tagars (1995: 153). Notably, corner slabs that were taken from earlier (Podgornovo) burial mounds, were set in the enclosure of mound 1 at Skalnaya-6, ignoring the images pecked on them. The Okunev stele shows only the lower part of the anthropomorphic mask, with the head outline in the area of the chin, the mouth made in relief in the form of a pecked recess of crescent shape, and three transverse lines between the nose and mouth (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, most of

Fig. 1 . Slab with anthropomorphic face from the enclosure of Tagar mound 1 at Skalnaya-6. All photographs by the author .

the image was eroded in ancient times and heavily weathered; the details are poorly visible even with special lighting.

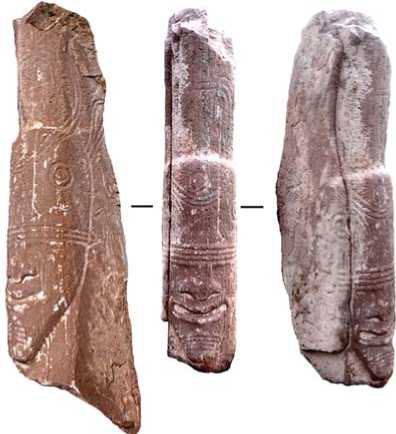

The stele-statue with anthropomorphic face from Uitag-3 was made of red sandstone. It was a part of the northern wall (northwestern corner) in the enclosure of mound 5 (Fig. 4). The structure was made of slabs placed on their edge. Slabs were selected by size and were set either overlapping, or edge-to-edge while wedging smaller stone plates on both sides and filling with earth, with virtually no buttresses or attempts to keep the same height level (Bogdanov, Timoshchenko, 2021: 898, fig. 2). Individual elements from this structure were taken by ancient builders from earlier structures: the corner stones belonged to Early Tagar burial mounds; four walls belonged to stone boxes with polished edges from the Bronze Age. The fragment of the Okunev statue was placed in the enclosure on its edge, with its “face” up (Fig. 5). The size of the fragment was 1.4 × 0.47 × 0.26 m (the reconstructed initial height of the stele was not less than 2.5 m). The degree of weathering suggests that the stone lay in the steppe on its left side for quite a long time before ending up in the Tagar enclosure. The right half was poorly preserved. Initially, the slab was probably “saber-shaped” (or close to it), approximately the same

Fig. 2 . Slab with anthropomorphic face from mound 1 at Skalnaya-6.

Fig. 3 . Drawing of anthropomorphic face on the slab. Mound 1 at Skalnaya-6. All trace drawings by E.A. Sazonova .

Fig. 4 . Slab with anthropomorphic face from the enclosure of a Tagar burial mound. Mound 5 at Uitag-3.

Fig. 5 . Fragment of the slab-statue in situ . Mound 5 at Uitag-3.

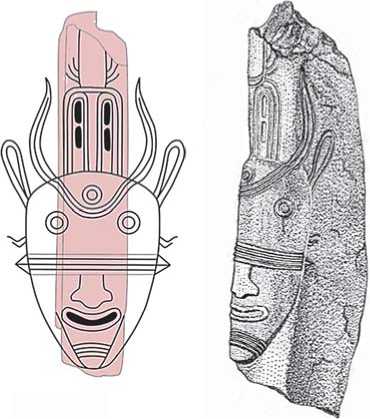

as a stele with the image of a human face in relief found near the Bir River (Vadetskaya, 1967: Pl. 6). The anthropomorphic profile was located in the lower part of the stele, on its edge, with a transition to the lateral sides. The pecked lines are deep, precise, and clearly stand out against the red-brown background of the slab due to their light gray color. A talented artisan carved a male face, which narrowed towards the chin. The image is convex; the chin is emphasized in relief (Fig. 6). The neck area is marked by three facets, which were cut off and polished. A wide nose with nostrils and a mouth are highlighted. Eyes in the form of concentric circles, with a convex “dot” in the center, are shown in the area of transition to the lateral sides. Three horizontal lines, separating the lower part of the nose, cross the entire face ending up in a triangle beyond its outline. Four lines arranged in an arc “cut through” the chin. A third eye is shown on the forehead as a circle with a dot. Pointed, saber-like, narrow leafshaped horns are depicted in the upper part of the head above the third eye expanding to the lateral sides. Animal elongated ears are slightly lower on the lateral sides. The upper part of pecking above the face is hardly distinguishable due to fragmentation and severe degradation of the stone surface. Most likely, this is a part of the surviving representation of a high stem-like headdress with geometric ornamentation and “hair” along the edges (Fig. 7).

Interpretation of the evidence

“Stone idols” or “stone babas”, as the first researchers of Minusinsk antiquities called them, serve today as a numerous, but very difficult historical source to interpret. Thus, it is not surprising that despite many articles and monographs (Vadetskaya, 1967; Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980; Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006; Esin, 2009), the internal chronology of the Okunev art remains unresolved, and semantics of its imagery causes heated discussions. Most trace-drawings of these pieces of art “roam” through the works of researchers as simplified drawings with inaccuracies and significant gaps, although modern equipment provides technical capacities for accurate reproduction of ancient pecked

Fig. 6 . Fragment of the slab-statue with anthropomorphic mask in relief. Mound 5 at Uitag-3.

Fig. 7 . Trace drawing of a fragment of the slab-statue with anthropomorphic mask in relief. Mound 5 at Uitag-3.

images (see, e.g., (Zotkina et al., 2021)). There is no generally accepted classification for the Okunev statues and pecked images, since it is difficult to formulate clear criteria for selection. The same images in the same pecking technique and manner of representation appear both on slabs and petroglyphs; they may be rendered in a realistic, stylized, or even abstract style. Taking into consideration realism and stylization of images, M.P. Gryaznov identified three groups—early, main, and transitional (1950: 131). E.B. Vadetskaya proposed the features of the mask, such as the headdress, and presence of bands on the face as a basis for classification, and also came up with three groups of images: simple, realistic, and complex non-realistic (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 40–42; Vadetskaya, 1983: 89). Y.N. Esin distinguished two groups of images: slabs (or rock surfaces) with the images pecked on the broad side, and column-like stones with the images and multi-tiered compositions in relief (2009: 21). More sophisticated and cumbersome classifications, proposed by N.V. Leontiev (1978: 93–94) and D.A. Machinsky (1997: 272–273), with classification into groups and subgroups (variants), were based on a variety of stylistic and semantic features of the images. Notably, among all manifestations of ritualistic and artistic creativity, nearly all scholars distinguish the special group of stele-obelisks (statues) with pecked images (compositions) extending from one surface to another. Only such “column-shaped” stones were set in sanctuaries with certain sacrificial offerings*, but not in the context of funerary rituals. D.A. Machinsky agreed with the opinion of S.V. Kiselev that high “obelisks” with elongated-ovoid three-eyed faces in relief, transverse bands, and animal ears and horns were created by the Afanasyevo people (Kiselev, 1962: 58; Machinsky, 1997: 272–276). However, the statement of Machinsky that “no statues of this group have been found during construction of the Okunev graves” (1997: 276) can hardly be accepted as the main argument in favor of this identification. The opinion of M.L. Podolsky that flat slabs with pecked masks found in the Okunev graves simply “belong to a different functional category associated specifically with funerary rituals” (1997: 186) seems to be absolutely correct. Thus, two basic postulates can be used for the next level of interpreting the steles found near Mount Uitag: a) pieces of Okunev art from more ancient sanctuaries that had not been originally associated with funerary rituals were found in the enclosures of Tagar mounds, and b) the statues were a result of the individual creativity of ancient sculptors.

This problem should be resolved using the analysis of the structure of the discovered ritualistic and artistic objects of art as a system: through search and comparison of parallels, identifying their common and specific aspects. One can note that there are no exact parallels to the slabs found on Mount Uitag. The stele from Skalnaya-6 (see Fig. 3), in its configuration and size of stone, remotely resembles some slabs near Lake Solenoye and near the village of Ust-Byur (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Cat. No. 169, 177). The outline of the head, mouth, and transverse bands above the mouth were rendered in a similar manner on a statue from the Uibat steppe (Ibid.: Cat. No. 85, pl. XXXVII), on the third stele at the Chernovaya VIII burial ground (Ibid.: Cat. No. 115), and on the slab from the Andronovo grave near Lake Solenoye (Ibid.: Cat. No. 137).

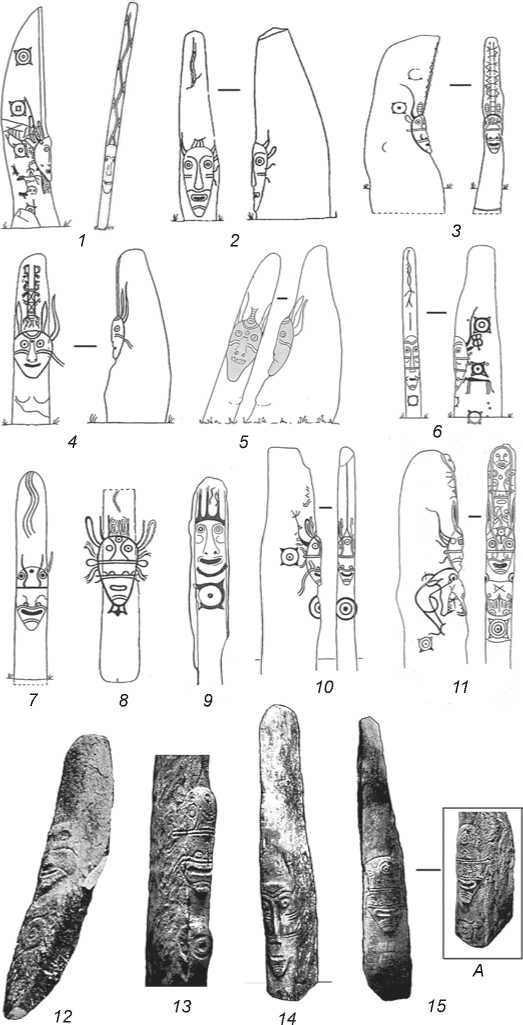

Several statues resemble the stele from Uitag-3 in their main compositional elements of the images: the three circular eyes, mouth, animal horns and ears, bands on the face, and high “headdress” (Fig. 8). However, a complete set of parallels to the entire image were not present on any of these. For example, most of the sculptures described in the literature have a narrow nose emphasized in relief, while a wide nose with nostrils was usually shown in a stylized manner*. The chin, together with the lower part of the anthropomorphic face, was always narrowed, but only on the statue from Uitag-3 was it emphasized in relief. One gathers the impression that the Uitag stele was a reference model for the subsequent “replica sculptures” made in accordance with certain traditions and mythological beliefs. Our statue is a brief, realistic image of a “male shaman” wearing a three-eyed animal mask and high headdress, without unnecessary details and additional symbols. The image on the Uitag statue should be viewed as a mask, which is an attribute of the material and spiritual culture as well as an intermediary between people and the other world (world of spirits). Bands on the mask and its “semi-animal” hypostasis are the keys to deciphering the semantic essence of the

*The fact that these stones acted as “sacrificial columns” was proven by I.T. Savenkova, E.B. Vadetskaya, and L.R. Kyzlasov by the excavations of the steles standing in their original locations (Vadetskaya, 1983: 87).

Fig. 8 . Stone statue-steles found in the Minusinsk steppe. 1 – single red sandstone statue (trace drawing), bank of the Byur River, Ust-Abakansky District, Khakassia (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Cat. No. 35); 2 – granite statue of “single stone placement”, right bank of the Ninya River, up the sources of the Kamyshta River, Askizsky District, Khakassia (Ibid.: Cat. No. 26); 3 – statue (menhir) made of brown sandstone, burial mound of Tasheba Chaatas, near the city of Abakan (Ibid.: Cat. No. 86); 4 – single statue “Khys tas” made of red sandstone, Lake Chernoye, Shirinsky District, Khakassia (Ibid.: Cat. No. 36); 5 – single red sandstone statue, bank of the Belyi Yus River (Gryaznov, Schneider, 1929: Pl. II, fig. 11, 1 ); 6 – statue made of red sandstone, sacrificial place, bank of the Es River, in the vicinity of the village of Ust-Es, Askizsky District, Khakassia (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Cat. No. 108); 7 – statue made of red sandstone, Uibat River valley, Ust-Abakansky District, Khakassia (Ibid.: Cat. No. 53); 8 – sculpture made of gray granite (face painted red), the enclosure of a Tagar burial mound, Uibat River valley, Ust-Abakansky District, Khakassia (Ibid.: Cat. No. 76); 9 – statue, bank of the Baza River, Khakassia (Vadetskaya, 1983: Fig. 3, 1 ); 10 – sculpture from the collection of the Minusinsk Museum (Vadetskaya, 1967: Fig. 5); 11 – statue, shore of Lake Shira, Khakassia (Vadetskaya, 1983: Fig. 14); 12 – sculpture made of gray granite, the “alley of stones” of Uibat Chaatas (Gryaznov, Schneider, 1929: Fig. 7); 13 – statue, bank of the Tasheba River, near the city of Abakan (Esin, 2009: 92); 14 – statue, bank of the Abakan River (Vadetskaya, 1967: Pl. 7);

15 – statue, bank of the Uibat River (Ibid.: Pl. 19).

functioned rather than how an organ looked” (1997: 182). However, this is not entirely true for the Uitag statue. Moreover, lines crossing the face in the nose area form only two zones. According to Podolsky, bands or “braces” on the “heavy Habsburg chin” only emphasized elongation of the mask by “balancing the upper zone” (Ibid.: 183). It is possible that the point was not in the composition balance, but in a special “status” of the chin, which was customary marked with tattoos or coloring during rituals among many ancient and modern peoples. According to the statistics on the Okunev sculptures, the number of bands (from 1 to 4) and their shape (arcuate, wavy, or straight) varied greatly regardless of the sex or degree of realism on the masks in relief. As for the three image. Most scholars believe that the pecked lines render coloring elements of an anthropomorphic facial mask or shaman’s face (Leontiev, 1978: 110; Vadetskaya, 1983: 90). According to Vadetskaya, 63 % of anthropomorphic faces on 126 steles had bands on the forehead, 83 % under the eyes, 63 % between the nostrils and mouth, and 34 % on the chin (Vadetskaya, Leontiev, Maksimenkov, 1980: 44, fig. 2). Podolsky suggested that ancient artisans specifically distinguished three zones with bands on the masks. Each zone corresponded to one of the sense organs. “The Okunev artist was interested in how it horizontal lines in the center of the facemask on the Uitag statue, special attention is to be paid to their triangular “end” in the area of the ears. These ends strongly resemble the fasteners fixing the mask to the head. This element played a special role in image creation, since most of the Okunev masks in relief show lace-strings (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Cat. No. 33, 35, 36, 45, 58, 62, 64, 65, 69, 76, 77, 86, 88, 103). There is usually only one carved line crossing anthropomorphic masks in the nose area on flat slabs, but also with “strings” behind the outline of the face (see, e.g., (Ibid.: Cat. No. 137)). From the viewpoint of similarities of cultural stereotypes, V.I. Molodin has discovered interesting parallels to the Okunev imagery in the Xinjiang evidence of the Xiaohe culture, which was contemporaneous to the Okunev culture (2019). These consisted of wooden masks from grave goods, each with a relatively wide belt of thin ropes, dyed with red paint and tightly adjacent to each other, located on the “face” in the area of the bridge of the nose (Ibid.: 14, fig. 2–6).

The mouth on the Uitag mask is shown customarily as open (a continuous recess). Such a “frozen smile of bliss” (Machinsky, 1997: 273) appears on masks of various peoples of the Old and New World, both ancient and modern. This similarity results from the common principles of mythological and ritual artistic creativity rather than from cultural contacts. Various examples include the ceramic head mask of a “goddess” from the Hongshan culture (China, 4th millennium BC) or antique theatrical masks made of terracotta. It should be admitted that the Uitag mask most likely shows the mouth of a person or deity (spirit), and not the half-open mouth of an animal. A well-known expert on masks of different peoples of the world A.D. Avdeev observed that in most cases “maskheads are made to be so large that nasal and especially mouth orifices are also exaggerated in size. <…> Due to the large size of the mask, the eyes of the masked person are not behind the eye holes (the need for which, therefore, disappears), but behind the nose and mouth openings of the mask, through which the dancer sees” (1957: 273). If an ancient sculptor, while pecking a mask, imagined a mask-head, it becomes clear why big, round eyes were shown in a stylized way on the lateral sides of the statue. Thus, the mask in relief on the Uitag statue is a reflection of three hypostases: human (lower part of the face), “otherworldly” (third eye), and animal (horns and ears). It was the third eye in the center of the forehead—the “sign of the Ajna Chakra” (Machinsky, 1997: 273), “solar symbol” (Kyzlasov, 1986: 235), and sign of “additional, superhuman sharpness of sight” (Vadetskaya, 1983: 90)—that symbolized the presence of another sense organ in the shaman, which was very important for performing various rituals.

Most Okunev anthropomorphic sculptures are distinguished by “correct” placement of animal ears and horns on the head. Such animal attributes extremely rarely appear on planar images of faces. On the Uitag statue, realistic pecking of details stand out (horns coming from the center of the forehead are above the ears, which are shown on the lateral sides), together with a long, “ornamented” vertical band going upwards from the head (see Fig. 7). The same

“ornamental band” occurs on other masks in relief of the Okunev period (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: Cat. No. 76). According to most scholars, such a “strict and obligatory combination indicates that we have an adornment of some kind of high headdress crowning the heads in most of the Yenisei idols” (Vadetskaya, 1967: 36). A headdress with bullhorns and ears is shown on most of the sculptures of the realistic group. This may be associated with cattle breeding in the Okunev population (Leontiev, 1978: 110).

Interpretation of the mask in relief on the Uitag statue from the viewpoint of universal (and specific) rituals performed at sanctuaries is based on assumptions. Possibly, this is the head of a real (or deceased) shaman wearing a horned mask and high cap carved in stone; this suggestion is consistent with the assumptions of Vadetskaya and Leontiev (Vadetskaya, 1983: 94; Leontiev, 1978: 109) and well-known ethnographic evidence*. It can be assumed that this was a “deified Vedic character” called the “Soul of the Bull”. He acted as an intermediary between the ancient cattle breeders and Ahura Mazda (Podolsky, 1997: 185). “The myth of a divine cow pregnant with a golden calf, which later became the life-giving sun, was widespread in ancient times among all peoples of the world”, while cow horns were a “symbol of divine power” (Kyzlasov, 1986: 207). The high headdress in a mythological and ritual context can be considered as the embodiment of the idea of the “World Pillar” or “World Tree” in a number of beliefs about some main “axis of the universe”.

Conclusions

Two new unique pieces of Okunev art were discovered during rescue excavations in the enclosures of Tagar burial mounds: a stone with fragmentarily surviving pecked mask and fragment of a “saber-shaped” slab with the anthropomorphic image of a facemask in relief. Analysis of structural features of the images has made it possible to formulate several conclusions. Some of them are consistent with the concepts commonly accepted in archaeology; others may clearly cause certain doubts and discussions.

-

1. The archaeological context of the steles testifies to different attitudes of the ancient local population towards the Okunev “statuary” monuments at various chronological stages of the Tagar culture.

-

2. Both slabs from the grave field near Mount Uitag belong to different groups according to the principle of image placement (on the broad plane of the slab and on the edges), but they are similar in the same pecking technique (deep counter-relief) and same rendering of details on the “face”. The general stylistic manner of representation indicates that both stones belonged to the same cultural and chronological (Early Okunev) stratum.

-

3. Neither of the slabs has exact parallels. In terms of stylistic, compositional, and semantic features, the obelisk from Uitag-3 shows some similarities to a group of realistic sculptures with images in relief extending from edge to edge. Obviously, this fragment of statue was the earliest and possibly “referential” example showing the embodiment of the realistic image of a “male shaman” wearing an animal mask and high headdress. The most important details convey the human (powerful chin and wide expressive nose), otherworldly (third eye and high headdress), and animal (expressive eyes, long horns and ears) hypostases of the image, reflecting the personal experiences and ideas of the ancient artisan who materialized the image of an intermediary between people and the other world, the world of spirits.

-

4. The sophisticated and diverse nature of Okunev art does not make it possible to give an unequivocal answer to the question as to why slabs with anthropomorphic images were set up near Mount Uitag. Excavations at the sites of ancient sanctuaries give scholars reason to consider stele-statues set there and oriented toward the sun as fragments of the “World Mountain” (Kyzlasov, 1986: 190) or “celestial pillars” (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006: 44). Bloody sacrifice mysteries were performed around them on calendar days that were particularly important for nomadic cattle breeders. It is quite possible that there were many more such obelisks with various kinds of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic faces; they could have been made not only of stone, but also of wood. The Okunev “visual texts” performed the same social function as religious hymns (prayers) addressed to superhuman powers (Ibid.: 36). Therefore, ethnographic data on the Siberian peoples, evidence on the religious and mythological ideas of the Vedic IndoAryans, and sources reflecting the complex world of symbolic anthropomorphic images from the Far East and Ancient China may be used in interpreting these images. However, these will be only some of many interpretations of ancient ritualistic and artistic creativity.

Acknowledgements

Список литературы Okunev statues at mount Uitag, Khakassia

- Aspelin J.R. 1931 Alt-Altaische Kunstdenkmäler: Briefe und Bildmaterial von J.R. Aspelins Reisen in Sibirien und der Mongolei 1887-1889, H. Appelgren-Kivalo (ed.). Helsingfors: K.F. Puromies Buchdruckerei.

- Avdeev A.D. 1957 Maska. (Opyt tipologicheskoy klassifikatsii po etnograficheskim materialam). SMAE, vol. 17: 232-346.

- Bogdanov E.S., Timoshchenko A.A. 2021 Kulturniy palimpsest v kurgane No. 5 mogilnika Uitag-3 (Respublika Khakasiya). In ProЬlemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXVII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 895-901. DOI: 10.17746/2658-6193.2021.27.0895-0901 EDN: YCZENZ

- Bogdanov E.S., Timoshchenko A.A., Ivanova A.S. 2021 Arkheologicheskiye raskopki na mogilnikakh "Skalnaya" v 2021 godu (Respublika Khakasiya). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. XXVII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 878-887. DOI: 10.17746/2658-6193.2021.27.0878-0887 EDN: ZQPAGN

- Devlet M.A. 1997 Okunevskiye antropomorfniye lichiny v ryadu naskalnykh izobrazheniy Severnoy i Tsentralnoy Azii. In Okunevskiy sbornik. Kultura. Iskusstvo. Antropologiya, D.G. Savinov, M.L. Podolsky (eds.). St. Petersburg: Petro-Rif, pp. 240-250.

- Esin Y.N. 2009 Taina bogov drevney stepi. Krasnoyarsk: Polikor.

- Gryaznov M.P. 1950 Minusinskiye kamenniye baby v svyazi s nekotorymi novymi materialami. Sovetskaya arkheologiya, vol. XII: 128–156.

- Gryaznov M.P., Schneider E.R. 1929 Drevniye izvayaniya Minusinskikh stepei. In Materialy po etnografi i, vol. IV (2). Leningrad: Izd. AN SSSR, pp. 63–93.

- Kiselev S.V. 1962 K izucheniyu minusinskikh kamennykh izvayaniy. In Istoriko-arkheologicheskiy sbornik. Moscow: Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ., pp. 53–61.

- Kuzmin N.Y. 1995 Nekotoriye itogi i problemy izucheniya tesinskikh pogrebalnykh pamyatnikov Khakasii. In Yuzhnaya Sibir v drevnosti. St. Petersburg: Izd. IIMK RAN, pp. 151–162.

- Kyzlasov L.R. 1986 Drevneishaya Khakasiya. Moscow: Izd. Mosk. Gos. Univ.

- Leontiev N.V. 1978 Antropomorfniye izobrazheniya okunevskoy kultury (problemy khronologii i semantiki). In Sibir, Tsentralnaya i Vostochnaya Aziya v drevnosti. Neolit i epokha metalla, V.E. Larichev (ed.). Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 88–118.

- Leontiev N.V., Kapelko V.F., Esin Y.N. 2006 Izvayaniya i stely okunevskoy kultury. Abakan: Khak. kn. izd.

- Machinsky D.A. 1997 Unikalniy sakralniy tsentr III – ser. I tys. do n.e. v Khakassko-Minusinskoy kotlovine. In Okunevskiy sbornik. Kultura. Iskusstvo. Antropologiya, D.G. Savinov, M.L. Podolsky (eds.). St. Petersburg: Petro-Rif, pp. 265–287.

- Messerschmidt D.G. 1962 Forschungsreise durch Sibirien (1720–1727): Tagebuchaufzeichnungen. Vol. 1: 1721–1722. Vol. 2: Januar 1723–Mai 1724. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Molodin V.I. 2019 Derevyanniye maski kultury syaokhe. In Problemy istorii, fi lologii, kultury, No. 2. Moscow, Magnitogorsk, Novosibirsk: [s.n.], pp. 7–19.

- Podolsky M.L. 1997 Ovladeniye beskonechnostyu (opyt tipologicheskogo podkhoda k okunevskomu iskusstvu). In Okunevskiy sbornik Kultura. Iskusstvo. Antropologiya, D.G. Savinov, M.L. Podolsky (eds.). St. Petersburg: Petro-Rif, pp. 168–201.

- Vadetskaya E.B. 1967 Drevniye idoly Yeniseya. Leningrad: Nauka, 1967.

- Vadetskaya E.B. 1983 Problema interpretatsii okunevskikh izvayaniy. In Plastika i risunki drevnikh kultur, R.S. Vasilyevsky (ed.). Novosibirsk: Nauka, pp. 86–97.

- Vadetskaya E.B., Leontiev N.V., Maksimenkov G.A. 1980 Pamyatniki okunevskoy kultury. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Zotkina L.V., Sutugin S.V., Postnikov N.V., Bogdanov E.S., Timoshchenko A.A. 2021 Metodika dokumentirovaniya naskalnykh izobrazheniy v kurgannykh konstruktsiyakh: Na primere pamyatnika Skalnaya-5 (Askizskiy rayon, Respublika Khakasiya). In Problemy arkheologii, etnografii, antropologii Sibiri i sopredelnykh territoriy, vol. ХХVII. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN, pp. 966–973.