Old Turkic stone statues from Taldy-Suu, Kyrgyzstan

Автор: Hudiakov Y.S., Orozbekova Z., Borisenko A.Y.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Art. The stone age and the metal ages

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.45, 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145330

IDR: 145145330 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2017.45.3.090-095

Текст статьи Old Turkic stone statues from Taldy-Suu, Kyrgyzstan

The intermountain depression where Lake Issyk-Kul is located is one of the areas of the greatest spread of medieval Old Turkic anthropomorphic stone statues on the territory of Kyrgyzstan and the entire Central Asian region. During the long history of studying archaeological sites in the Tian Shan, Russian scholars have found many anthropomorphic stone statues associated with the Old Turkic culture of the early Middle Ages, in the Issyk-Kul Basin. This article presents the history and main results of research into Old Turkic stone statues on the territory of the intermountain depression where Lake Issyk-Kul is located.

According to D.F. Vinnik, information about several dozen “stone figures” on the northern shore of the lake appeared as early as the beginning of the 19th century (1995: 160–162). Later, Russian researchers described, made drawings, and proposed chronological and cultural attribution of these sites. In 1856, during a trip to Issyk-Kul, the Russian military officer C.C. Valikhanov, a famous Kazakh scholar and traveler, described and drew several medieval stone sculptures from the area along the coast of the lake “from Sarybulak to the Kurmet River” (Күрмөнтү) (1984: 341–342). The following year the famous Russian traveler P.P. Semenov-Tyan-Shansky visited the lake and examined several stone statues on the northeastern shore in the valley of the Tyup River (Semenov, 1946: 182–183). Some information about these studies was published by the authors of the present article earlier (Hudiakov et al., 2015: 109). From the 1850s–1870s, stone statues on the shore of Issyk-Kul were mentioned by other Russian scholars, local historians, and lovers of antiquities. In 1859, stone sculptures in the Tyup Valley to the northeast of the Lake were examined by A.F. Golubev. In 1869, G.A. Kolpakovsky found face stelae on the northern shore in the Koy-Suu area; he discovered one of the statues under the water near the shore of Issyk-Kul (Vinnik, 1995: 160–162).

In the 19th century, information about medieval “stone figures” in the Tian Shan, including Lake Issyk-Kul, attracted the attention of some Russian researchers

of Siberia and Mongolia. The famous traveler in Siberia and Central Asia N.M. Yadrintsev wrote about the similarity of these sculptures to “stone figures” found in Southern Siberia and Mongolia, and noted both male and female sculptures among the finds in Tian Shan. As with some of his predecessors, Yadrintsev associated the stone sculptures from the vicinity of Issyk-Kul with the ancient nomadic Wusun tribes. At the same time, he did not reject the views of other scholars that the figurative representations from Central Asia might have belonged to the Old Turks. Yadrintsev was one of the first scholars who tried to systematize the stone sculptures on the territory of Kyrgyzstan by identifying two groups of statuary: those only representing facial features, and those depicting a human figure with a vessel and weapons on the belt (1885: 19–21). In the late 19th century, stone statues in the vicinity of Lake Issyk-Kul were mentioned by other Russian lovers of antiquities. For example, A.V. Selivanov noted that there were many such sculptures in the Issyk-Kul Basin. One of the lovers of antiquity D.L. Ivanov suggested a “Kalmyk” origin of the medieval stone figures. The researcher A.N. Krasnov wrote that “stone figures” were set on burial mounds. In the late 19th century, several stone sculptures on the southern shore of Issyk-Kul were examined by A.M. Fetisov, who associated them with the Mongols (Ploskikh, Galitsky, 1975: 19). Several medieval “stone figures” near Lake Issyk-Kul were discovered by F.V. Poyarkov (Vinnik, 1995: 162–164). In the 1890s, the famous Russian expert in the history of Central Asia V.V. Bartold surveyed a number of stone statues in the Issyk-Kul Basin, and presented his considerations on their chronological and cultural attribution, as well as the functioning of the stone sculptures, in an article on the results of his field research in 1893–1894. He attributed these figures to the Early Middle Ages and to the culture of the Old Turks of the 7th–8th centuries (Bartold, 1966a: 38–39). Later, in a special article, Bartold suggested that the anthropomorphic stone sculptures were set up by the Old Turks on the burial complexes of their dead relatives (1966b).

From the 1930s–1950s, the stone statues in the Issyk-Kul Basin were studied by the archaeologist A.N. Bernshtam. Several sculptures were surveyed on the northern shore of the Lake, in the vicinity of the villages of Oy-Bulak and Kurmenty. These were statues of warriors with vessels in their right hands, daggers, and swords in a sheath hanging from their belts, and a figure without weapons (Bernshtam, 1952: 79–81, fig. 42, 1–3; 43). Old Turkic sculptures in the works of Bernshtam and some other archaeologists working in Central Asia, were often called the balbals (Bernshtam, 1952: 79; Albaum, 1960: 96). In the 1960s, during the study of stone sculptures in the Altai-Sayan, a discussion about whom exactly the Old Turkic stone statues represented emerged among archaeologists. According to the majority of scholars, the representations rendered the appearance of the Turks who were commemorated at the time of the memorial ritual, and not their “main enemies”, while the balbals (stone posts) symbolized dead enemies (Grach, 1961: 66; Kyzlasov, 1966; 1969: 37–43). Scholars argued that there were no balbals found at the memorial complexes of the Western Turks and Turgeshes, while stone sculptures included female and children’s figures (Tabaldiev, 1996: 61–82; Hudiakov, Tabaldiev, 2009: 68–88).

In the 1960s, Y.A. Sher continued the study of stone statues in Semirechye and Tian Shan. The materials that he gathered were analyzed in a special monograph. Sher systematized the sculptures and suggested the chronological and cultural attribution of the types of sculptures that he identified. He noted that the statues were located near some ritual enclosures (Sher, 1966: 14, 22–29, 40, 90, 106). At the same period, D.F. Vinnik studied Old Turkic stone sculptures in Kyrgyzstan and found a significant number of previously unknown medieval stone sculptures in the vicinity of Lake Issyk-Kul (1995: 174–175).

In the 1970s to early 1980s, many stone figures were transported from their original locations to museums, cultural centers, and schools in various places of the Chuy Valley and the Issyk-Kul Basin. Unfortunately, memorial constructions were not investigated in the process, and the locations from which the stone sculptures were taken were not recorded. During this period, V.P. Mokrynin studied stone statues in the Issyk-Kul Basin (Mokrynin, Gavryushenko, 1975). He paid special attention to the analysis of sculptures represented as wearing a “threehorned” headdress. Mokrynin suggested that these monuments were associated with the ancient nomadic tribes of the Ephthalites (1975). The well-known Kyrgyz archaeologist K.S. Tabaldiev made a great contribution to the study of stone statues in the territory of Kyrgyzstan (1996: 61–70; 2011: 130–143). In the course of his field research in the Central Tian Shan, he discovered Old Turkic funeral enclosures with stone statues, belonging to memorial complexes. Tabaldiev discovered some rare sculptures, which survived in the places of their original setting. His joint research with the co-author of this article resulted in confirmation that stone sculptures in Tian Shan and the entire Central Asia were set up at Old Turkic memorial sites (Tabaldiev, Hudiakov, 2000: 66–70; Hudiakov, Tabaldiev, 2009: 68–87).

A large number of medieval stone statues have been discovered in the territory of the Issyk-Kul Basin in Kyrgyzstan, and a considerable part of them have been published. In the valley of the River Ton in the southeastern part of the Issyk-Kul Basin, the authors of this article together with their Kyrgyz colleagues took part in the study of distinctive fully or partially preserved stone sculptures, which were attributed to the culture of Western

Turks and Turgheses of the 7th–8th centuries (Hudiakov et al., 2015: 113). Despite the fact that such sculptures have been studied in the Issyk-Kul Basin for many decades, archaeologists still continue to find and study previously unknown medieval stone anthropomorphic figures on its territory.

Description of stone statues

During the expedition to the Issyk-Kul Basin in August 2014, which was organized as a part of the project, “History of Warfare of Ancient and Medieval Peoples of Southern Siberia and Central Asia”, supported by the Interstate Development Corporation, in the area of the village of Taldy-Suu in the eastern part of the basin, the authors of this article examined two original anthropomorphic stone statues, currently located in the private household of a local resident. The figures are set up on both sides of the gate at the entrance to the fence of this household. According to the owner of the estate V. Fomenko, he discovered these stone sculptures during agricultural work on the field of a collective farm, located near the village. He also informed us that the female statue had been associated with a structure resembling a mound built of stones, which looked like a stone “barrow”. In connection with cleaning collective farm fields from stones, which could impede plowing, both stone figures were relocated by this resident of Taldy-Suu and were set up at the entrance to his household*.

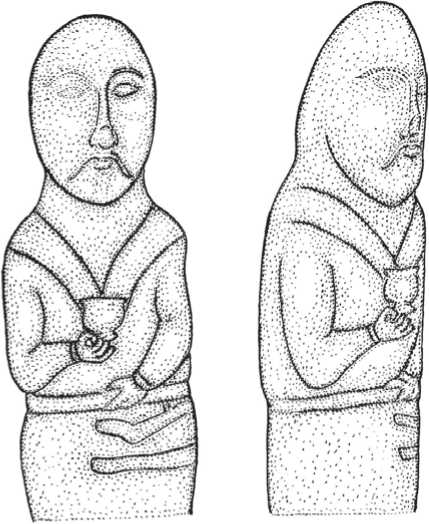

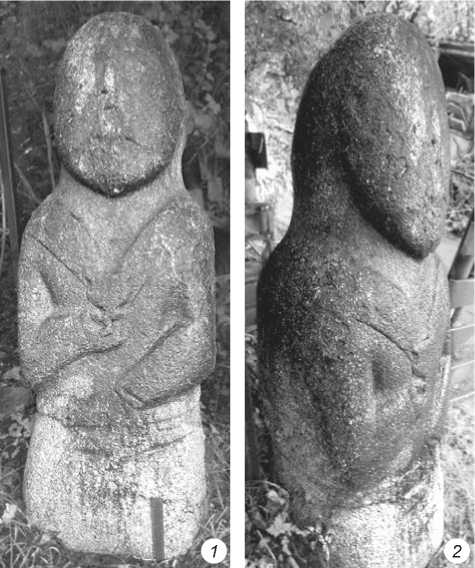

According to the attributes preserved on the statues, it can be established that one sculpture is the representation of a male, probably a warrior (Fig. 1, 2). The height of the sculpture above the ground is 1.43 m; the width is 0.42 m. The figure has a distinctive, large head. Probably, the warrior was represented wearing a spherical headdress, although presently it is not possible to see any of its details, since the head, in particular the facial section, has been partially damaged. However, arched eyebrows and large almond-shaped eyes marked with low relief, a partially broken off straight nose, a long mustache with pointed ends, and an arched lower lip can still be seen on the head. A face of smooth oval shape prominently expands from the massive neck. Wide lapels of upper robe-like clothing, probably a khalat, converging in the middle of the chest, are depicted on the shoulders and chest of the statue. The right arm is shown bent at the elbow. With bent fingers, the figure is holding, at the level of his chest, a vessel with the rim folded outward and a spherical body. There is a protrusion resembling a small, somewhat curved conical tray, shifted to the side under the bottom of the vessel. The left arm is shown slightly bent at the elbow; the palm of the left hand rests on the belt. Narrow cuffs are marked on both sleeves of the khalat. The belt is represented in the frontal area of the waist. A bent dagger, which is suspended from the belt on hanging straps, is shown below the belt on the left side. The dagger has a sheathed blade, with the crossbar and the handle bent at an angle. The belt is marked by a continuous horizontal band. A longer sheathed bladed weapon with smoother curve can be discerned below the dagger. It is likely a sheathed saber, suspended from the belt. The features on the lower part of the statue are not clearly visible. We may assume that initially the belt with the weapons could have been seen more distinctively, but the prominent features of relief were abraded over time. According to some distinctive details represented on other Old Turkic sculptures that were discovered on the territory of the Tian Shan and Semirechye, the figure in question can be attributed to the first type of stone statues (male statues with a vessel in the right hand and weapons on the belt) identified by Sher (1966: 25–26, 90).

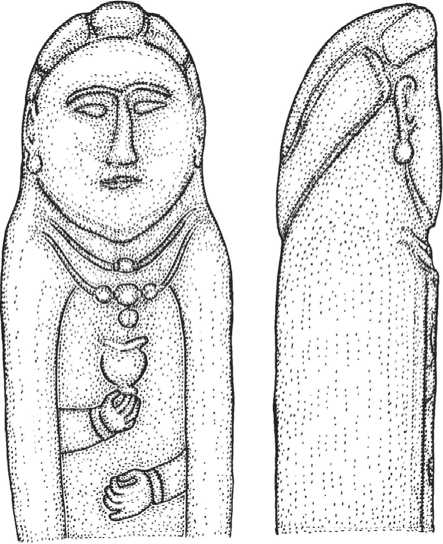

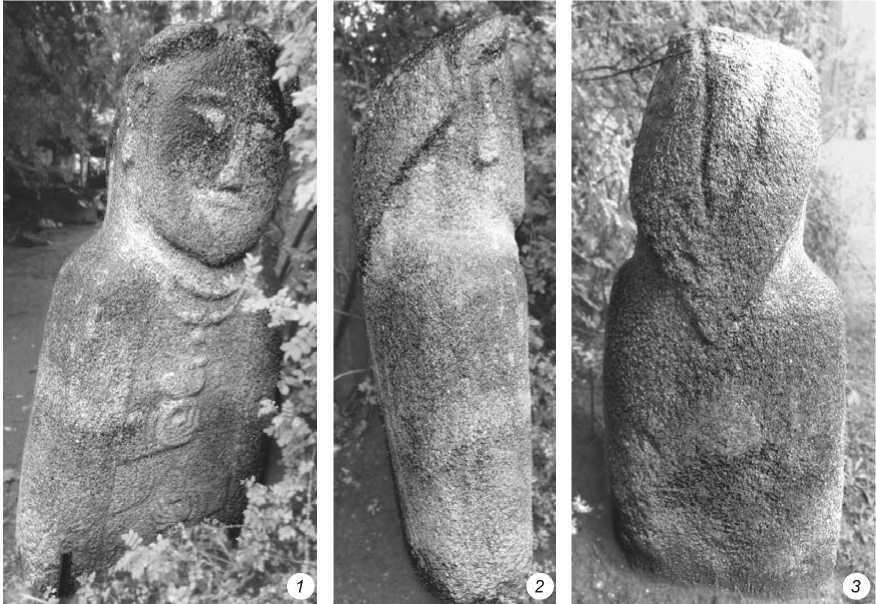

Another, relatively large and robust stone sculpture from the village of Taldy-Suu represents an Old Turkic woman (Fig. 3, 4). The height of the statue above the ground is 1.72 m; the width is 0.6 m. Three semicircular protrusions separated by depressions are located on the head, forehead, and temples of the figure. They may represent a “three-horned” female headdress typical of many sculptural representations of Old Turkic women, or long hair combed back and divided into three parts in front above the forehead, indicating a certain hairstyle with the hair joined together on the top and back of the head, forming a wide wedge converging in the upper part of the back. There are reasons to suggest that a soft felt headdress similar to a cap or hood, common to many nomadic peoples, is thus depicted. The sculpture has a large, broad face of oval shape with arched eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, straight nose, narrow, tightly pressed lips, and softly outlined chin. Relatively large ears decorated with earrings with pendants are represented on both sides of the head. Two necklaces are shown on the neck and upper chest. There is a large bead in the central part of the upper necklace. In the center of the lower necklace, three large spherical beads are shown. A similar large round bead is suspended from the middle bead. The right arm of the woman is bent at the elbow; her fingers are holding the tray of a vessel, which looks like a goblet with a tray. The vessel has a rim, folded outward, and a spherical body attached to the tray. The left arm is also bent at the elbow; the fingers are represented. The shoulders and elbows of the woman are covered with clothing resembling a cloak or cape without sleeves. This female statue does not show a belt—an attribute of the Old Turkic male outerwear complex, which was usually depicted on female figures. This sculpture can be

Fig. 1. Stone statue of a male warrior from the vicinity of the village of Taldy-Suu. Drawing.

1 – front view; 2 – profile view.

Fig. 2 . Stone statue of a male warrior from the vicinity of the village of Taldy-Suu.

1 – front view; 2 – profile view.

attributed to the type of female stone sculptures with a vessel. According to Sher, this sculpture shows the image of a male (Ibid.: 26, 106), which is difficult to agree with.

This female statue attracts our attention by its hairstyle divided into three parts, and some features of the headdress. The analysis of these elements makes it possible to clarify the shape of the “three-horned” headdresses represented on many female stone statues found in the area of the western version of Old Turkic culture, including the Tian Shan and Semirechye (Hudiakov, Tabaldiev, 2009: 75–79; Tabaldiev, 2011: 134–135).

Given the style of representations, the postures, which aim at rendering a specific image, the features reproduced, and the presence of the vessel in the right hand, both figures can be identified as stone sculptures set up at memorial monuments of Old Turkic people. Judging by the detailed treatment of features, the figurative sculptures under consideration belong to the period when the Western Turkic and Turgesh Khaganates existed in Central Asia and the adjacent territories in the 7th–8th centuries AD. At that time, the art of creating Old Turkic stone sculptures in the Cis-Tian Shan region, Semirechye, and the adjacent territories of Central Asia and Eastern Turkestan reached a high level of development. It is quite possible that the sculptures found in the vicinity of the village of Taldy-Suu were originally set up at Old Turkic memorial complexes. As noted above, the female

Fig. 3 . Stone statue of a woman from the vicinity of the village of Taldy-Suu. Drawing.

1 – front view; 2 – profile view.

Fig. 4 . Stone statue of a woman from the vicinity of the village of Taldy-Suu. 1 – front view; 2 – profile view; 3 – back view.

representation was discovered on the surface of a stone structure, a “barrow”, which could have been a memorial complex. It is also possible that our sculptures were associated with the memorial complexes of the nomadic elite of the Western Turks or Turgeshes. The impressive size of the statues and the thoroughness of treatment of certain details argue in favor of this suggestion. Along with the common features typical of many Old Turkic stone sculptures, both sculptures from the village of Taldy-Suu have their own distinctive features.

Conclusions

Old Turkic stone figures that were found and explored by the authors of this article near the village of Taldy-Suu have a great value for the medieval history and culture of Kyrgyzstan. The fact that the sculptures were found by one of the local residents and were moved to his household in order to preserve them, shows the careful attitude of the population toward the monumental artifacts. It is known that in the late 1950s to early 1960s, on the initiative of the Kyrgyz authorities, many stone statues in the Tian Shan were transported from their initial locations to museums of local history, cultural centers, and schools. Thus, the sculptures have survived until today and are available for study. Unfortunately, the places of the original finding of sculptures were not always recorded, which was probably caused by the perception of Old Turkic anthropomorphic stone sculptures as independent monuments outside of their relationship with funeral enclosures. At the same time, examples of negative attitudes toward stone statues are also known in the Central Asian region: during the period of the spread of the world’s proselytist religions, people would break off faces and heads from the sculptures, and in some cases they used the statues as hitching posts and even building material for modern buildings. It is to be hoped that in time, the medieval stone statues from the village of Taldy-Suu will find their place in one of the museums of Kyrgyzstan.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 14-50-00036).