On phoinix and its distinguishing marks: a Karian “type site” or a demos to Hellenistic kamiros?

Автор: Ouz-krca E.D.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The oldest known inhabitants of Taşlıca (Bozburun Peninsula, in Southwestern Turkey), recorded as Phoinix in the inscriptions, were the Tloioi people. In the light of the ancient Greek corpus reported especially from the site of Fenaket (namely Rumevlek, forming the core of the dwelling zone) and the Classical wall ruins at the Acropolis, it is understood that the village has been systematically occupied since the 5th century BC. The settlement, which grew as a dominion of Kamiros as of the 3rd century BC, expanded its territory in the NE-SW axis over the centuries. Although Phoinix’s chess-board system of insulae of the megara offers parallels with Kamiros, owing to its Hellenistic-style plan and layout, it contains clues to far more ancient codes. In this study, besides being greatly equated with the Hellenistic period, Phoinix’s identity in the historical process, which gives indications of her Karianism, is discussed with the help of selective materials, basically authentic architecture tracked over the region. Apparently, the pyramidal monoliths were not unique to Phoinix; however, the Tloans, like the other neighboring komai on the mainland, seem to have managed to keep their traditions of communication with the “other world” through such features. Hence, these monoliths, which evoke the ziggurat morphology or the famous Mausoleum at Halicarnassus to connect to the afterworld, must have been the typical manifestations of the Karian mentality, sufficiently reflected by the aboriginal communities, however inevitably overshadowed by the grandest architectural projects of the Hekatomnid dynasty.

Karian Khersonesos, Bozburun, Rhodian Peraia, Tloioi, Gökçalça, pyramidal monolith

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146804

IDR: 145146804 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.3.082-091

Текст научной статьи On phoinix and its distinguishing marks: a Karian “type site” or a demos to Hellenistic kamiros?

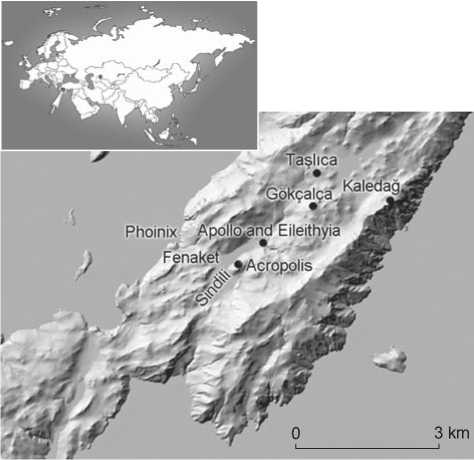

The Karian communities of the Bozburun Peninsula in Southwestern Turkey (Fig. 1) entered into various organizations from the 5th century BC, and founded regional unions under the generic model of the Karian Federation. The basis of such associations went back to much more ancient times. The name of the union established in the Peninsula was the Karian Khersonesos (Strabo, XIV , II, 1; Cook, 1961: 56–57). It was equated with a large polis and minted its own coins.

The Khersonesos was annually paying an average of 3 talents (about 78 kg of silver, a paltry amount as compared to the tributes of the famous cities) to the superpower of the period, the Athenian State. All the villages/ demoi of the Peninsula had a share in the payment of this tribute, while Phoinix was just one of them. Things changed with the rise of the Rhodian State onto the stage of history. The Peninsula became a semi-flexibly administered colony of Rhodes, recognized as the “Rhodian Peraia”, from the end of the 3rd century BC till 166 BC, when the Romans banned Rhodes from its territory on the mainland.

A polyonomous village

Phoinix* is paired with the modern village of Tallica, meaning “rocky area”, true to its name. The recorded expression of Phoinix (Oolvi^) (Searchable Greek Inscriptions, ASAA2: 167, 121)** or Phiniki, on the historical maps of Kiepert, may have been associated with the Phoenicians or palm tree (phonetic derivative of phoenix dactylifera** *). In the ecoregion of the demos , the Phoenix theophrastii palm is also known (Boydak, 1985; Kemeç, 2018). Other options sound extralogical. In later periods, from 1936 to the 1950s, when the region experienced outmigration, due to population exchange following victory in the Independence War of Turkey, the appellation of the core settled area turned into Fenaket in the dialect of the local people. As Fenaket’s center of gravity shifted northward in the same interval, the village, where the Turkmens were settled, took its present name, Tallica.

In the region, the earliest known site (Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 290–307), which was occupied before the Classical period, lies immediately south of Tallica, over the skirts of the two shallow hills Gökçalça and Somakkaya (Fig. 2). Following the Karian heyday, in the Hellenistic period, Phoinix became a subordinate of Kamiros (Meyer, 1925: 50, pl. I; Fraser, Bean, 1954: 80; Robert, 1983: 257; Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 284), when the Rhodians officially had their feet on the mainland. The political, social, and economic impacts the insulars left in the demos have come to be known, with quite a good many inscriptions that were overwhelmingly reported from the upper and lower settlement by the early travelers, and with those surviving in several localities on the Island of Rhodes. The Hellenistic corpus also reveals that the ancient inhabitants of Phoinix were identified with the people

Fig. 1 . Location of Phoinix.

of Tloioi (Gärtringen, 1902). A notable mention of the ethnicon was made on a 3rd century BC stele found in the northeast corner of the Acropolis. Accordingly, the task of Nikasimènés, as the prytane of the demos of the Tloans, ended (Chaviaras M., Chaviaras N., 1913; Bresson, 1991: No. 153, p. 150).

The given territory of Phoinix extended over an area of ca 2824 ha, near Thyssannos (modern Sogut village) and Kasarae (Bozuk village). In the domain area also lay Elaeiussa Island (on the east) and Fenaket Island (on the west). In the direction of Serçe Harbour and passing through Kırkkuyular location, where dozens of wells and cisterns occur, in the heart of ancient Fenaket, there appears the living soil of Sindili Plain— a depression, traversed by the NE–SW orientation fault. This locality is one of the untouched tranquil landscapes of the Peninsula, with an uncontaminated environment, also describable with a rural economy and livestock tradition, dominated by goats and donkeys. In the dearth of forests but dominance of shrubland biome, territories below the radar were systematically renewed with the motion of herds over the centuries, which at the same time created suitable conditions for growing quality figs and almonds on stony arid land. The key to the region’s rural treasury used to be viticulture, which suited the terraced lands of the Mediterranean, shiny almost all year round. Abandoned or presently cultivated, terrace relics highlight the sweaty labor of the farmers since archaic times. Water is the scantest agent drilled from underground reserves. The way in which Phoinix coped with hydrological problems made her a master in this field. The village’s longing for fresh water is embodied in wells and cisterns.

Fig. 2 . Gökçalça site, with rock-cut dwellings.

The Acropolis and bigwigs out from Gökçalça

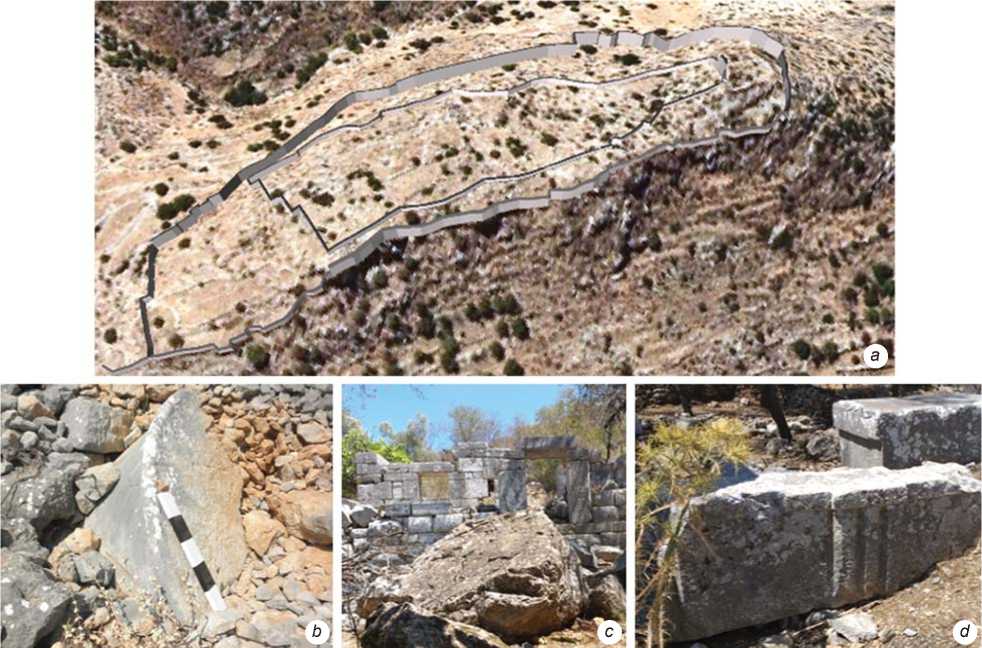

The Acropolis (double-topped Hisartepe, inhabited since the 5th century BC) covers an area of ca 2.6 ha (Fig. 3, a ) and rises over the Sindili Plain, neighboring Karayuksekdag. The summit enjoys a spectacular view of the Aegean as far as Symi and the lower “city” Rumevlek. On its wings, the ramparts, which were mostly worked out in the Hellenistic period, are traced; whereas a ruined wall southward remained from the Classical era. To the east, there is the entrance to the fortress. Compatibly with the topography, the outer ramparts draw the contours of the hill (on Phoinix acropolis and reconstruction trial, see (Oguz-Kirca, 2014)).

As a Classical and Hellenistic hub, the Acropolis was the civic administrative center. Another gigantic mass named Kaledag (Ibid.), with a phrourion on top (Ibid.: 285), which must have acted as a shelter at times of risk, rises in the moderately distant khora, on the east of Tallica. Maintaining a very high visibility, this stronghold must have supported and guarded the Acropolis while watching the boundaries, i.e. in the case of a siege or attack from the “illegal” groups patrolling in the Mediterranean. This nearly trapezoidal-plan garrison (Ibid.: 294-295, 307-308; Oguz-Kirca, 2015a: 132-136), with the boulder ramparts, must have burdened its military function over time and survived into many centuries. The ramparts, which were greatly worked with Lesbian masonry, fit well to the topography. Not that far off the Acropolis, but closer to modern Tallica, there is an earlier settlement (accessible through a narrow valley on its eastnortheast). Its probable relation to the Archaic period is suggested by the masonry technique (in the dearth, so far, of datable evidence on topsoil). The settlement was speculated to match a dale, Gökçalça, which is within sight of Kaledag. Maintaining quite an invisible position, this inland site hosts a minimum of 35 rock-cut dwellings, built using boulder blocks and often reposing on the bedrock on the one side (see Fig. 2) (Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 290–291, 294–296, 302, 307).

The estimated perimeter of the diateikhisma (varying between 300–500 cm height, and 120 cm width) and outer walls (height between 150–500, with an approximate width of 100 cm) are 510 and 770 m, respectively. On the summit, there are six cisterns; some basic coordinates of relative importance match the eastern sector and the near environs of the Classical wall’s ruin. A clear evidence of social engagement, providing insight also into the religious realm of the inhabitants, is contained in an insitu rock-hewn 3rd century BC inscription (ca 150 cm high) listing the names of the donors (Rhodian citizens

Fig. 3 . Acropolis ( a ), mega elements, remains of the columns ( b , d ), and traces of the Apollo sanctuary ( c ).

and possibly local elites as Tloans) for the construction of a sanctuary dedicated to Dionysus, found on the northeast (an estimated locus is given in (Oguz-Kirca, 2014, 2015a: 473))*.

The vast majority of the epigraphic records were recovered on the reused stone walls of the historical houses in Rumevlek. The inscription on a 3rd century BC (255/236 BC) marble block (dated in connection with another name appearing on the above-mentioned donor list) contains a list of priests (Bresson, 1991: No. 148, p. 139–145). At the height of the Hellenistic period, particularly by the middle 3rd century BC, in the administrative system of the Island, there participated priests of Athena Polias and Zeus Polieus, Asclepius or Sarapis, etc. (and perhaps those incorporated to the system of matroxenoi (Foucart, 1889: 366–367) who were the offspring of intermarriages between the priestly or commercially important Tloans and Rhodians (often from a Rhodian citizen and a free Peraian mother) holding certain privileges, i.e. acting as the official

*The greatest amount donated, 120 drachmae, was made by only one man, Rhodippos, son of Nikagoras (Bresson, 1991: No. 149, I.6, p. 144–148); the rest was paid as 20, 25, 30, 50, or 100 drachmae by about 70 men (Dürrbach, Radet, 1886: No. 2, p. 252–258).

demesmen to bring public recognition to their homeland). Notwithstanding this, there are quite a number of traces of political and social life with the participation of local rulers holding the position of prytanis, child athletes from Phoinix, family epitaphs, foreigners, etc. (Bresson, 1991: No. 137–172, p. 135–160).

Kamiros and Phoinix

Following the collapse of the Hittite Empire (1200 BC) and when the western coasts of Asia Minor began to be colonized by the Aeolians, Ionians, and Dorians (ca 1000 BC), the lack of organized power in Anatolia gave rise to new settlements. Around the same period, Dorians arrived at Rhodes, Cos, Halikarnassos, the adjacent islands, and near Karia up to the Meander (Bean, 1979: 2–6). Particularly coastal Karia, by then, entered in the domain of the Dorian Hexapolis, which was formed by Cos, Cnidus, Halicarnassus, Lindos, Ialysos, and Kamiros as separate autonomous poleis .

After her long strife for synoecism, the city of Rhodes was probably founded in the month of Καρνεῖος*,

Fig. 4 . Megara of Phoinix and Kamiros.

i.e. in October/November of 408 BC (Badoud, 2014: 25). Having strived for synoecism, Rhodians began to institutionalize with the oligarchic administration of the Diagoras family, who took over authority by making Rhodes the capital. Diagoras originated from a titled family of Ialysos. He is known as a famous boxer who won the Olympics in 464 BC and won championships in many other semi-Olympics. He was one of the rare fathers to witness the victories of his sons and grandsons in the competitions. Diagoras had a share in bringing together three phylae : Ialysos in the north, Lindos in the east, and Kamiros in the west. The first is called an aristocrat, the second a merchant, and the third a farmer. Notably, Diagoras made effort to keep these three old poleis of the Dorian Island all together, considering the lineage relations as family rather than religious ties.

Lindos was a city of seamen and merchants, Kamiros was a treasure with an agricultural character, growing olives, vines, and figs. Kamiros was established on a hill, about three km west of Kalavarda village. The 6th–5th centuries BC marked its golden age; in 226 BC, the city was severely damaged by the earthquake that toppled the Colossus, and by the second tremor 84 years later. Despite all, this grid-planned Hellenistic polis (Fig. 4, b ), where a sewer-design system can be clearly observed, is the best-preserved settlement on the island.

Phoinix, as affiliate of Kamiros, reveals a Hellenistic-style plan and layout, with unequal divisions of zones: (i) Acropolis, (ii) the lower settlement with megaron dwellings (Fig. 4, a ), forming a chess-board system of insulae at Rumevlek (covering a broad span of time from the Classical to the Roman period), and (iii) agora and temenos of Apollo and Eileithyia. The tight and orderly arrangement of the megara surrounding Sindili (the great majority of which catch the eye by the modern road to Serçe Bay) looks similar to the Kamiran districts.

Temenos of Apollo and Eileithyia

Situated next to a dried-up stream-bed in Sindili, between Burgaz Tepe and Gökseriç, a small public structure (Chaviaras M., Chaviaras N., 1913; Bresson, 1991: No. 145, p. 138; Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 287, 293-294, 303, 305) naiskos (which was later turned into a chapel with spolia) is hidden among fig trees. This structure is at fair a distance from the Acropolis, connected via an ancient trail. The stream-bed was first noted as Kislan Deresi/Creek Kizlar/Ki^lar (?) by the Chaviaras brothers (Chaviaras M., Chaviaras N., 1913; Bresson, 1991: No. 145, p. 138). The area of temenos and naiskos is not designated on any ancient map, not even those of 5000 plots.

The chapel is oriented due east, with the entrance facing west (see Fig. 3, c ). The plan is clear in the frontal part. The original structure was perhaps built in the Doric order (in this regard, noteworthy are the neighboring sanctuaries, c.f. the Doric temple of Apollo at Kamiros (Caliò, 2011: 348) and the shrine of Sinuri at Mylasa (Williamson, 2016: 87)). The naos behind the portico is small. A remnant of a small altar, a column base, and a socket where a statue could have been placed (re-used on the wall) can be seen toward the entrance. At the entrance, engraved inside the walls, below the gate lento, there was an inscription from the Hellenistic period (ca 250/101 BC), with the names of the god Apollo (“ΑΠΟΛΛΩΝΟΣΠΕ”) and, slightly below it, the goddess Eileithyia (“EΛEIΘYAΣ*) (Dürrbach, Radet, 1886: 258–259, No. 4, 5; Bresson, 1991: No. 151, 152, p. 49). As attested, Apollo was one of the five principal deities of Phoinix. Thus, the original construction of the sacred area can be dated to the Early Hellenistic period. The clarity of the Apollo inscription indicates that he could have been a chief figure, despite many other deities enlisted with their associated priests, as noted earlier (Bresson, 1991: No. 148). There is another illegible inscription in Karian script seen on a façade (along with the one on the gate lento) (Oğuz-Kırca, 2022a: 1206, 1209). The reused ashlar and stepped blocks, particularly those with triglyphs (see Fig. 3, d ) between the metopes, seemingly belonged to a distinguished building. Probably there was a cistern in the southwestern courtyard. In accordance with chronologization of many other inscriptions in Phoinix (see (Bresson, 1991: No. 135–160, p. 134–154)), the entire context points to the period between the 4th and 2nd centuries BC.

Phoinix was a purely agricultural land, with lots of herdsmen. The discovery of three large-size farmsteads, which were reported from three sectors of the demos , contributed to the corroboration of its agrarian character (Oğuz-Kırca, Demirciler, 2015: 54, 59, 71; Oğuz-Kırca, 2014: 284, 289–291, 294, 300–301)**. In fact, a dedicatory inscription in a temple of Dionysus (Bresson, 1991: No. 149, p. 145–149; Oğuz-Kırca, 2014: 284, 286, 304–305), the terrace relics in the close vicinity of the temple, and the rest of the khora relate to some other basic landmarks, such as farmsteads and associated agrarian installations, although no standing part of the structure is present***.

Presumably, cult practices survived into centuries, without breaking with the essence of the Karian religious

*For a critique of Eileithyia at Phoinix, see (Oğuz-Kırca, 2016: 240.

**A fourth one, as yet unpublished, lies in the western part of the demos .

***Hypothetically localized on the Acropolis, close to the stone containing the donation list, and can be related to the enclosure as if peeking out of the ground (Oğuz-Kırca, 2014: 284, 286, 304–305).

patterns. At this point, the co-existence of Apollo and Eileithyia indicates that they can be regarded as the original cults worshipped in the region (Oğuz-Kırca, 2022b); and these cults almost manifest themselves at the very heart of the rebuilt chapel, where divinityspecific offerings (wine, incense, and honey) must also have been made in the late Antique period and thereafter. A possibility is that the original sanctuary was related to agriculture. In this respect, there is no reason why the temple of Dionysus should not be attributed to the sanctuary of Apollo, as long as this is validated through the introduction of convincing evidence in the near future, also in view of the cult of Apollo Erethimios found in Rhodes.

Going deeper, it is worth dwelling on the wording “Apollonos Pe” in the inscription. It may designate a Peraian (τό Πέραν) Apollo, or Apollo Petasitas (Bresson, 1991: No. 151, p. 149), who was linked with the rural landscapes and the soil itself. Notably, part of a workshop (now in the form of reused material) and its remnants lie on an adjacent field in the temenos area. The space may find expression in the agricultural context, as it might have had a relation to a torcularium (utility dwelling where juice- and oil-presses were kept). The name of Petasitas evokes the typical Thessalian round winged hat petasos (Bonfante, 2003: 73, 75)*, identified with Hermes, and worn by the farmers (as is depicted on Ainos tetradrachms) (May, 1950: 253b).

There can be another interpretation of adding “Pe” after the name of a deity. The winter month of Pedageitnyos, references to which occur in Kamiros in the 3rd century BC (Tit. Cam. 155, I.1)** or in the Doric calendar of Rhodes (Prittchett, 1946: 358; Birch, 1873: 137)***, can be related to Apollo Pedageitnios (Stoddart, 1850: 38, 40; Le Guen-Pollet, 1991: 111).

Once again acknowledged from Kamiros, one more interpretation may involve the Roman Apollo Petasitas or Petasites (Tit. Cam. 132, I.1). It is believed that the goddess Eileithyia eases the pains of women during their labor and delivery, or migraine attacks (Grossman, Schmidraml, 2001). Thus, Apollo’s epithet might have corresponded to the antispasmodic attributes of the herb Petasites hybridus (butterbur)****. Whatever the answer is, Apollonos Pe still remains a unique name.

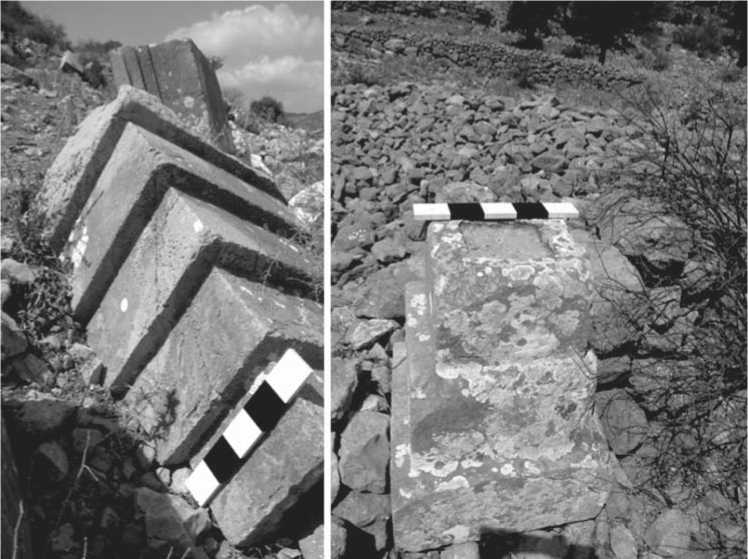

Fig. 5 . Stepped monoliths at the Acropolis.

Retroreflectors as pyramidal monoliths

Looking at the structural background, lateral stepped monoliths, sometimes used as gateposts or occasionally as locking blocks, alongside with pyramidal ones, often diagnosed as the altars and/or tomb elements, form the basic architectural repertoire of Phoinix. Pyramidal monoliths, appearing in varying sizes, by and large with three to four steps (Fig. 5), are typical designs of the Peninsula, while they may also be encountered at other localities (Fig. 6). On this matter, Carter drew parallels with Lycian and Egyptian geographies (1982: 178–179)*. Pyramidal stepped monoliths were sufficiently observed in Tymnos, Kasarae, and Hygassos, although almost all detached from their contexts. There are, also, enough of these structures in mainland Greece and the islands (see (Liritzis, Vafiadou, 2005: 32–36)). Pyramidal stepped monoliths with slots on top were supposedly used as grave-markers over the pit graves or pedestal tombs for the commemoration of the deceased, especially the influential individuals (in either off-site slopes or spots away from the visitors); whereas lateral monoliths were possibly part of the sacred buildings, or constructions of a public character. On the other

*His view may not be considered unsuitable. For further pyramids, see also (Oguz-Kirca, 2015b: 60, fig. 5; 2022a: 1205, 1208).

hand, there are not enough data to attach any value to ascriptions such as “hidden” or “strange” to these pyramids, which are often met in tourism channels and internet publications. Much of this information is being used in non-academic media.

The northern sector, particularly the plain strait between the Acropolis and Burgaz Tepe, has been referred to as a necropolis in some sources, owing to a scattering of a handful of pyramidal monoliths (Bent, 1888: 82–83; Hicks, 1889: 47; Carter, 1982: 184–195; Bean, 2000: 168)* and a few more elegant features (see (Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 301–302)), but is mainly connected with the modern perception of this place. It should be reminded that most of the inscriptions found on the stelae and addressed in the epigraphical corpus (Bresson, 1991: 34–154, No. 135–159) in the megara of Fenaket were found outside their original context. With a few blocks that appear on the slopes of the Acropolis, it is quite problematic to mark the area as a burial-space.

Something to be underscored also is that not all the pyramidal monoliths belong to funerary monuments. These could have been used as various architectural features or parts thereof. Pyramidal monoliths could

Fig. 6 . Pyramidal monoliths of Phoinix and the neighboring demoi .

have fallen off a sanctuary situated on elevated ground. Equally possible is that the stone block with the names of Apollo and Eileithyia could have been transported from its original location.

Conclusions

The abandoned territories of the Bozburun Peninsula in the southwestern corner of Asia Minor, which demonstrate evidence of various types of site (often with rural architecture), have been gradually giving a fresh stimulus to the blooming interest of scholars, so far. The very picture of the Phoinix khora , for instance, is well represented by the three large-sized farmsteads mentioned above (Oguz-Kirca, Demirciler, 2015), which at the same time highlight that the countryside was a region controlled by the Kamiran or other Rhodian “vassals”. The proximity of the precinct of Apollo to the Acropolis allows for the interpretation of this site as a sanctuary for rural dwellers.

The odds are that, as a landscape protected by divinities like Dionysus and cultivated by the Tloan farmers, Phoinix had a premier role because of the lavish plain of Sindili (embodied by terraces), which was convenient for growing cereals, grapes, olives, and perhaps figs (which are best grown on barren land) and almonds, as it is today. Since agriculture was of primary concern to the Peraian communities, excessively living on fragmented land, the dispersed settlement patterning (see (Oguz-Kirca, 2014: 289-300, 307)) must have persisted during the late Antique period, too. Also, many terraced plots near Gökçalça suggest the implementation of intensive agrarian activity since the earliest known times around the region.

As a far land of the Karians and a longtime isolated site for centuries, Phoinix was merely one of the demoi testifying to the typical stepped pyramids, often appearing as a bunch of relocated, sometimes flipped monolithic blocks here and there, down the Acropolis (but not over the plain of Sindili). These sites contribute to the generation of an idea about the owners’ wish to hide out from the transients, rather than showing off their workmanship. When the original outlook of the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos (Pedersen, 1994) as the crescendo of Karian eclectic architecture is redeliberated, pyramidal stepped monoliths may retroreflect to the Classical origins of the region. Evocating the ziggurat morphology in all likelihood, these grave-structures were perceived as vehicles of the spirit of the heroized or deified Late Classical personalities. The dearth of any frieze is explainable by the financial nonproficiency of the rural landscape and its owners. Alongside the prominent cultic objects, whose symbolism mainly results from the longstanding ties with Rhodes, an implicit statement of Karianism was ensured through authentic architecture, which permitted its durability through the centuries.

In Taşlıca, the days when the agricultural terraces of value as cultural heritage, fields where donkeys and jades (similar to the Przewalski’s horse) run, and products such as figs and vine will be brought to eco-tourism, may be near. These will need to be combined with the architectural heritage of the village.

In spite of Kamiran fingerprints, reflected especially in private planning and agrarian focus, as well as through the epithets of some chief deities or goddesses carved onto public walls, Karians seem to have managed to keep their tradition of communication with the other world. The presence of the inscription in Karian script, discovered inside the temple of Apollo, confirms the Karian identity of the demos . The pyramidal monoliths of the Peraia and Phoinix must have been typical manifestations of the Karian mentality. This is sufficiently reflected by the aboriginal communities, however inevitably shadowed by the grandest architectural projects of the Hekatomnid dynasty.

Список литературы On phoinix and its distinguishing marks: a Karian “type site” or a demos to Hellenistic kamiros?

- Badoud N. 2014 The chronology of inscription to the chronology of Rhodian amphora eponyms. In Pottery, Peoples and Places: The Late Hellenistic Period, c. 200-50 (B.C.) Between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, M. Lawall, P. Guldager Bilde (eds.). Aarhus: Aarhus Univ. Press, pp. 17-28.

- Bean G.E. 1979 Aegean Turkey. London: E. Benn Ltd.

- Bean G.E. 2000 Eskiçağ’da Menderes’in ötesi, P. Kurtoğlu (transl.). İstanbul: Arion.

- Bent J.T. 1888 Discoveries in Asia Minor. Journal of Hellenic Studies, No. 9: 82-87.

- Birch S. 1873 History of Ancient Pottery, Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman. London: J. Murray.

- Bonfante L. 2003 Etruscan Dresses. Baltimore; London: John Hopkins Univ. Press.

- Boydak M. 1985 The distribution of Phoenix Theophrasti in the Datça Peninsula, Turkey. Biological Conservation, No. 32: 129-135.

- Bresson A. 1991 Recueil des inscriptions de la Pérée Rhodienne (Pérée Intégrée). Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- Caliò L.M. 2011 The Agora of Kamiros: A Hypothesis. In Η Αγορά στη Μεσόγειο: Από τους Ομηρικούς έως τους Ρωμαϊκούς χρόνους: Διεθνές Επιστημονικό Συνέδριο Κως, A. Giannikouri (ed.). Aɵήνα; Yπoυρεγεio Пoλιtισμoύ και Toυρισμoύ, Apχαιoλoγικό Iνστιτoύτo Aιγαιακών Σπoυσών, pp. 343-355.

- Carter R.S. 1982 The stepped pyramids of the Loryma Peninsula. Istanbuler Mitteilungen, No. 32: 176-195.

- Chaviaras M., Chaviaras N. 1913 Archaiologike Ephemeris, No. 95: 4.

- Cook J.M. 1961 Cnidian Peraea and Spartan coins. Journal of Hellenic Studies, No. 81: 56-72.

- Dürrbach F., Radet G.A. 1886 Inscriptions de la Péréé Rhodienne. Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, No. 10: 245-269.

- Foucart P.-F. 1889 Inscriptions Attiques et inscriptions de Rhodes. Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, No. 13: 346-367.

- Fraser P.M., Bean G.E. 1954 The Rhodian Peraea and Islands. London: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Gärtringen F.H., von. 1902 Anhang über die Tloer. Hermès, Bd. 37, H. 1: 143-146.

- Grossman W., Schmidraml H. 2001 An extract of Petasites Hybridus is effective in the prophylaxis of migraine. Alternative Medicine Review: A Journal of Clinical Therapeutic, vol. 6 (3): 303-310.

- Gyllenbok J. 2018 Encyclopaedia of Historical Metrology, Weights, and Measures. Vol. 1. Cham: Birkhäuser.

- Herda A. 2013 Greek (and our) views on the Karians. In Luwian Identities: Culture, Language and Religion Between Anatolia and the Aegean, A. Mouton, I. Rutherford, I. Yakubovich (eds.). Leiden; Boston: Brill, pp. 421-507.

- Hicks E.L. 1889 Inscriptions from Casarea, Lydae, Patara and Myra. Journal of Hellenic Studies, No. 10: 46-85.

- Kaya Z., Gümüş C. 2018 Balamba tabiat parkı (Bartın) florası. Bartın Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, vol. 20 (2): 311-339.

- Kemeç S. 2018 The evaluation of the impacts of the climate change on Datça-Bozburun SPA with geospatial data and techniques. In Proceedings, 7th International Conference on Cartography and GIS, 18-23 June 2018, Sozopol, T. Bandrova, M. Konečný (eds.). Sofia: Bulgarian Cartographic Association, pp. 140-147.

- Le Guen-Pollet B. 1991 La vie religieuse dans le monde Grec du Ve au IIIe siècle avant notre ère: choix de documents épigraphiques traduits et commentés. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail.

- Liritzis I., Vafi adou A. 2005 Dating by luminescence of ancient megalithic masonry. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, vol. 5 (1): 25-38.

- May J.M.F. 1950 Ainos, Its History and Coinage. London: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Meyer E. 1925 Die Grenzen der Hellenistischen Staaten in Kleinasien. Zürich; Leipzig: Verlegt Bei Orell Füssli

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2014 Restructuring the settlement pattern of a Peraean Deme through photogrammetry and GIS: The case of Phoinix (Bozburun Peninsula, Turkey). Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, vol. 14 (2): 281-313.

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2015a The Ancient population of a Chersonessian Heir: Phoinix (Kersonesoslu bir varisin antik nüfusu: Phoinix). Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi, vol. 34 (58): 445-488.

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2015b The Chora and the Core: A general look at the rural settlement pattern of (Pre)Hellenistic Bozburun Peninsula, Turkey. Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi (PAUSBED), No. 20: 33-62.

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2016 Tymnos’un kayıp mabedi: Hera ve Zeus’a adanan tapınak neredeydi? Arkeoloji ve Sanat Dergisi, No. 151: 231-247.

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2022a Karian fi ngerprints: Stepped pyramid and script as markers of identity, at home and afi eld. International Journal of Science and Research, vol. 11 (4): 1205-1209.

- Oğuz-Kırca E.D. 2022b Yerel ve Devşirme? İki Kimlik: Hemithea ve Eileithyia. Belleten, vol. 86 (306): 427-467.

- Oğuz-Kırca, E.D., Demirciler V. 2015 Antik dünyada kırsal ekonomi: Karya Kersonesosu’ndan yeni kanıtlar. Anadolu, No. 41: 51-76.

- Pedersen P. 1994 The Ionian Renaissance and some aspects of its origin within the fi eld of architecture and planning. In Halicarnassian Studies I: Hecatomnid Caria and the Ionian Renaissance, J. Isager (ed.), vol. 1. Odense: Univ. Press of Southern Denmark, pp. 11-35.

- Prittchett K. 1946 Month in Dorian calendars. American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 50 (3): 258-360.

- Robert L. 1983 Une épigramme Hellénistique de Lycie. Journal des savants, No. 4: 241-258.

- Rumscheid F. 1994 Untersuchungen zur kleinasiatischen Bauornamentik des Hellenismus. Mainz: Ph. von Zabern.

- Searchable Greek Inscriptions (PHI): A Scholarly Tool in Progress (The Packard Humanities Institute Project Centers). (s.a.) Aegean islands, incl. Crete (IG XI-[XIII]): Rhodes and S. Dodecanese (IG XII,1), Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene [ASAA2], Segre & Pugliese Carratelli, Tituli Camirenses (ASAtene 27-29) [Tit. Cam.]. URL: http://epigraphy.packhum.org/inscriptions/main (Accessed August 30, 2021).

- Stoddart J.L. 1850 On the inscribed pottery of Rhodes, Cnidus and other Greek cities (read June and November, 1847). In Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom. 2nd ser., vol. III. London: J. Murray, pp. 1-127.

- Tys J., Szopa A., Lalak J., Chmielewska M., Serefko A., Poleszak E. 2015 A botanical and pharmacological description of petasites species. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, vol. 28 (3): 151-154.

- Umar B. 1993 Türkiye’deki Tarihsel Adlar. İstanbul: İnkılâp Kitabevi.

- Williamson C.G. 2016 A Carian shrine in a Hellenizing world. In Between Tarhuntas and Zeus Polieus: Cultural Crossroads in the Temples and Cults of Graeco-Roman Anatolia, M.-P. de Hoz, J.P. Sanchez Hernández, C.M. Valero (eds.). Leuven; Paris; Bristol: Peeters, pp. 75-101. (Colloquia Antiqua; No. 17).