On the Angara petroglyphic style

Автор: Ponomareva I.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145264

IDR: 145145264 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2016.44.2.69-80

Текст статьи On the Angara petroglyphic style

The Angara style or the Angara tradition is a specific manner of representing elk (Alces alces) and deer in rock art. For the first time, the term was introduced by N.L. Podolsky in 1973 for designating a vast array of rock art of the Neolithic-Chalcolithic, characterized by realism of representations (Podolsky, 1973)*. The concept has found its place in the archaeological literature, but still remains not quite clearly defined. Representations are assigned to the Angara tradition rather by intuition than on the basis of specific stylistic features.

The petroglyphs of the Angara were first published by Okladnikov, who proposed their first attribution (1966). He dated the group of realistic representations to the Serovo and Kitoy periods, that is, to the third–second millennia BC (at the present, these cultures are dated to the sixth–fourth millennia BC). In his earlier publications, Okladnikov dated the realistic representations of elk which were found among the Shishkin petroglyphs, to the Neolithic (1959: 42). The same chronological framework was extended to other sites on the Upper Lena and the rock art sites of Yakutia (Okladnikov, 1977: 117; Okladnikov, Zaporozhskaya, 1972: 77; Okladnikov, Mazin, 1976: 90). A considerable number of representations among the Tom petroglyphs, including the “realistically represented

drawings of elk” (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972: 183) were dated to the Neolithic. The similarity of representations and their “realistic” stylistic features were explained by the common material culture and worldview prevalent among the inhabitants of Northern Europe and Asia in the Neolithic Age, caused by the common geographical environment. Although contacts might have occurred, they must have been indirect, and there was no significant migration of the ancient population (Ibid.: 239).

The article of Podolsky, mentioned above, appeared after the publication of the monograph, The Treasures of the Tom Petroglyphs . In his article, Podolsky offered his analysis of the Angara and Yenisei petroglyphs by identifying specific stylistic features of representations. He united the representations of elk into a single Angara tradition, also including similar representations from the Tom petroglyphs. Using the materials of the Yenisei sites, Podolsky also identified the Minusinsk style. Comparing it with the Angara style enabled him to conclude that the Angara style was ecdemic to the Yenisei area. In addition to a distinctive iconography described by fourteen specific features, the Angara style is distinguished by the technique of gentle relief, which was adapted in the Yenisei area for the local motifs. Podolsky also noted that the elements of the identified styles continued to exist for a long time (1973).

Another point of view was expressed by A.A. Formozov, who emphasized the differences between the Tom petroglyphs and the Angara petroglyphs. On the Tom, there were more anthropomorphic representations, entire compositions were rendered from a sophisticated angle, and a “skeletal” manner of depiction was typically used for figures (Formozov, 1973).

Sher suggested that the Angara style might have spread in two directions, to the east and to the west, and the starting point was the Minusinsk Depression. This conclusion seemed forced even to him, since it relied on the chronological framework proposed by Okladnikov and contradicted Sher’s own stylistic observations (1980: 190).

Since 1977, B.N. Pyatkin and A.I. Martynov conducted research at the sites of the Minusinsk Depression, including the Shalabolino rock art site on the Tuba River. The site contained a significant number of representations which Pyatkin and Martynov attributed to the Angara style (1985: 118). On the basis of analysis of the Yenisei petroglyphs, O.S. Sovetova and E.A. Miklashevich did not entirely reject the influence of the Angara tradition, but came to the conclusion that this style on the Yenisei was of local origin and originated from the development of the Minusinsk style (1999).

Scholars traced the influence of the Angara style in the Altai, at the Turochak and Kuyus rock art sites. At Turochak, there was only one representation of elk that resembled the Angara images, showing the animal in side view and in motion. V.I. Molodin dated it to the Okunev period (1993). Several representations of elk were found at the Kuyus rock art site. Associations with the Angara style emerged during the first examination of the site (Frolov, Speransky, 1967). Later, E.A. Okladnikova also noted the distant resemblance of these representations to the Angara petroglyphs and concluded that there were contacts between the creators of the Shishkin, Tom, and Altai petroglyphs in the third–second millennia BC (1984: 61). Some examples of the Angara style were found to the east of the Angara area, on the banks of the upper and middle reaches of the Lena River and its tributaries.

When assigning representations to the Angara style, scholars noted their realistic manner, which is not a clear definition. Other identified features (the elk is shown in side view and in motion) are formal. The only attempt to give a clear definition of the style using fourteen features was made by Podolsky, but there is no evidence that his definition was adopted by other scholars. The lack of a clear idea of the Angara style, and the intuitive attribution of individual representations have triggered debates concerning the history of this tradition, its development, and directions of its dissemination.

In order to understand what the Angara style really was, we need to analyze in more detail the entire array of representations which have been assigned to that style, and retrace its development in time and space. First, we should make an overview of the existing viewpoints on the chronology of the Angara style.

A.P. Okladnikov dated the representations of elk using parallels with horn sculptures from the Bazaikha burial ground, which he dated to the Neolithic. He used one and the same figurine for dating both the Angara petroglyphs and later the Tom petroglyphs. However, the dating of the Bazaikha burial ground is not definitive. After analyzing its goods and burial rite, S.V. Studzitskaya concluded that the site belonged to the Chalcolithic (1987). In another study into the sculpture of the Early Bronze Age from the Upper Angara, Studzitskaya compared the representations of elk with an exaggerated upper lip, with the figurine of an elk’s head from the Shumilikha cemetery (1981: Fig. 57), which made it possible to date both of them to the Early Bronze Age (Ibid.: 41). The dating of the Bazaikha burial ground has become the starting point for a discussion concerning the time when the Angara style existed, which was initiated by the publication of the Angara petroglyphs. Some scholars agreed with attributing the Angara tradition to the Neolithic (Sher, 1980: 189–190; Pyatkin, Martynov, 1985: 118; Formozov, 1967), while others believed that it flourished in the Chalcolithic (Podolsky, 1973; Studzitskaya 1981, 1987).

The long-term studies of N.N. Kochmar in Yakutia have led to results which support dating the Angara style to the Neolithic. Having examined the archaeological materials which were found near the rock art sites, Kochmar built a chronological diagram showing the development of rock art in the region. He correlated the representations of elk which can be attributed to the Angara style, with the Early Neolithic Syalakh culture (4th millennium BC) and the Middle Neolithic Belkachi culture (3rd millennium BC). At the next stage, in the Late Neolithic (Ymyyakhtakh culture, 2nd millennium BC), iconography of elk is completely different; anthropomorphic representations have also been attributed to that time (Kochmar, 1994: 135–141). The results of Kochmar’s research confirm the importance of the cultural turning point from the 3rd to the 2nd millennium BC and make it possible to specify the lower border for the existence of the Angara style, which is thus pushed back to the Initial Middle Neolithic in the territory of Yakutia. This thesis requires more arguments, but the Yakut rock art sites have not yet attracted a significant number of researchers, as, for example, did the Tom rock art site.

The Tom rock art site has been studied for the last 300 years (see, e.g., (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972: 9–21; Martynova, Martynov, 1997; Kovtun, 2011)). In recent decades, new representations have been discovered and new data have been obtained using modern techniques (Miklashevich, 2011; Zotkina, 2010; Kovtun, Rusakova, 2005; Kovtun, Rusakova, Miklashevich, 2005; Martynov, Pokrovskaya, Rusakova, 1998; Rusakova, Barinova, 1997). Two different points of view are expressed in the academic literature concerning the age of the elk representations, attributed to the Angara style. The first view was proposed by Okladnikov (see above), but was further elaborated by Martynov, according to whom the “Tom” or the “Angara-Tom” style emerged in Western Siberia in the Late Neolithic at the turn of the 4th–3rd millennia BC and evolved until the beginning of the 1st millennium BC (Martynov, 1997). Arguing for this position, Martynov referred to numerous bone and stone elk figurines, recently found at the Neolithic sites of the Northern Angara region, and concluded that the Tom rock art site was a complex multi-layer monument which functioned as a sanctuary for several millennia. Another view was suggested by Molodin, who analyzed the Turochak rock art site dated to the Okunev period (1993). The same view was supported by I.V. Kovtun, who argued that the entire stratum of the “Angara” representations in Western Siberia should be attributed to the Okunev and later periods, since the representation of elk among the Turochak petroglyphs was covered by the representation of the bull (Kovtun, 1995: 20; 2001: 123; 2005: 20).

If we combine all points of view, the chronological framework of the Angara style appears to be very wide, from the 4th–3rd millennia BC in Yakutia to the 1st millennium BC in Western Siberia. Such a chronology may be caused by the vagueness of the Angara style definition. Kovtun dated the “Angara” representations to the later time, while considering the depictions hardly similar to the Angara representations. When Martynov spoke about the Angara-style, he meant only the Tom petroglyphs. Moreover, the emergence and development of the Angara style in Eastern Siberia occurred at an earlier time than it did in Western Siberia. However, the core of the problem is not the dates, but which images correspond to the dates. Thus, a priority is to formulate an accurate definition of the actual Angara style and to consider the time of its existence on the basis of that definition.

Stylistic analysis of representations

We may see the internal dynamics of the Angara tradition on the basis of three multi-figure compositions from Kamenny Ostrov II on the Angara River, the most representative site of the tradition. There are a number of palimpsests at the site, which are an important source for establishing the relative chronology. However, we need to keep in mind that the time gap between the depictions of various figures is unknown. The analysis of the palimpsests is not the only method for clarifying the chronology, and scholars time and again return to the sites of rock art for getting new information. Unfortunately, the petroglyphs of the Kamenny Ostrov sites were flooded by the Bratsk Reservoir, and the book by Okladnikov and his archival materials are now probably the only sources for further study of the Angara petroglyphs.

The analysis of the palimpsests was made using the photographs of petroglyphic images from the collection of field materials gathered by Okladnikov (The Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg Branch, F. 1099*). Some photographs of petroglyphs have been published (Okladnikov, 1966). However, the originals are of much higher quality than the illustrations in the book, which made it possible to see some inaccuracies in the drawings. Unfortunately, the archival materials cannot yet be published, since the collection of Okladnikov is still undergoing scientific and technical processing. Thus, the results of the analysis will be illustrated by the published drawings of the images (Ibid.: Pl. 42, 62, 65).

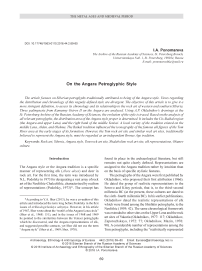

Individual layers of representations have been identified in the images (Fig. 1), and they will be designated by Roman numerals (Table 1). In the first image (Fig. 1, A ), the earliest figures are No. 3, 5–7, and 9, because they do not overlap any other representations and are the worst preserved. These are a pair of animals with long necks, rectangular heads, and large torsos. This group is overlapped by the representation of the elk (figure No. 8), a distinctive representative of the Angara tradition. Judging only by the drawing, it may seem that it does

С

Fig. 1. Palimpsests of Kamenny Ostrov II (after (Okladnikov, 1966)).

Table 1. Sequence of painting representations

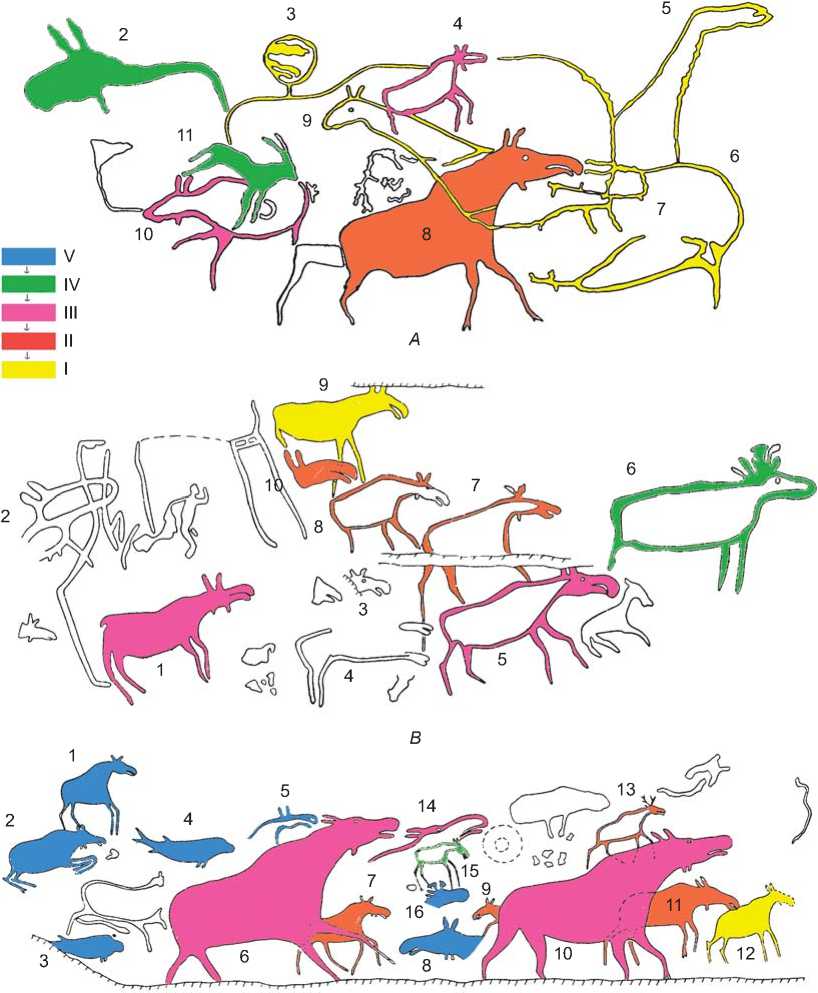

Fig. 2. Stylistic layers on the palimpsests of Kamenny Ostrov II (after (Okladnikov, 1966)).

Representations 1* and 2 were engraved separately, possibly already in the space that remained. They are also stylistically uniform: the shape of the head is angular and rectangular; the outlines of the body are broken, and only the backs of the animals are visible.

The second image (Fig. 1, B ) does not show the same layers as the previous one, but it is still possible to see instances when the legs of the represented animals expand to the backs of the adjacent figures: representations 8 and 10 overlap representation 9, while figure 5 covers figure 7. Representations 1, 3, and 6 are arranged freely; figures 2 and 4 have barely survived.

The third image is the most vivid and sophisticated (Fig. 1, C ). In total, five groups have been identified.

It can be clearly seen which images are covered by other depictions. It seems that figures 6, 10, and 14 were drawn by the same hand; they cover figures 7, 9, 11, and 13, which also look similar to each other. Figure 11 lightly touches figure 12, and it can be concluded that figure 12 was made earlier than the two groups. Figure 15 was engraved over figure 14, and was attributed to layer IV. There remained some images which were not included in the palimpsest processes. They are sufficiently homogeneous and can also be combined into a group with the exception of two figures, No. 2 and 16.

Thus, the following summarized sequence can be established, where the letters refer to the images (see Fig. 1), and the Roman numerals refer to the layers of the images (Fig. 2):

-

1. AI,

-

2. CI, AII, CII, CIII, CIV, CV(–2,16),

-

3. AIII, BI,

-

4. BII, BIV(+16), AIV.

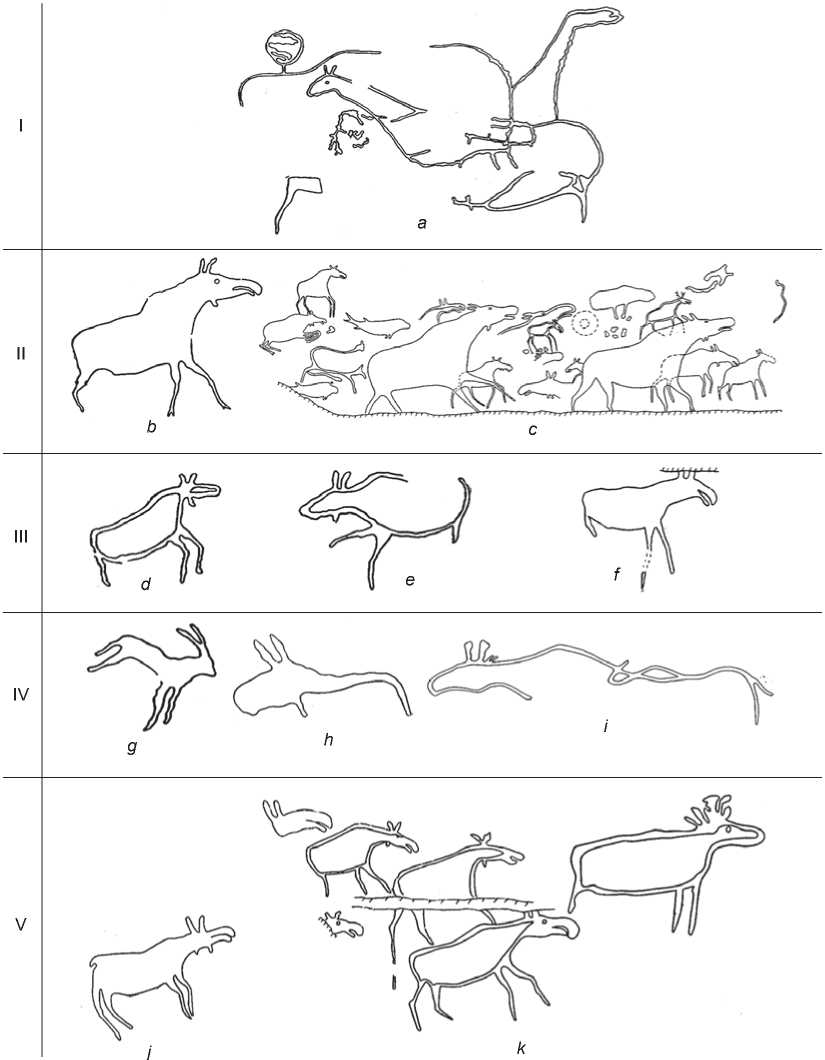

Fig. 3. Examples of the groups of representations.

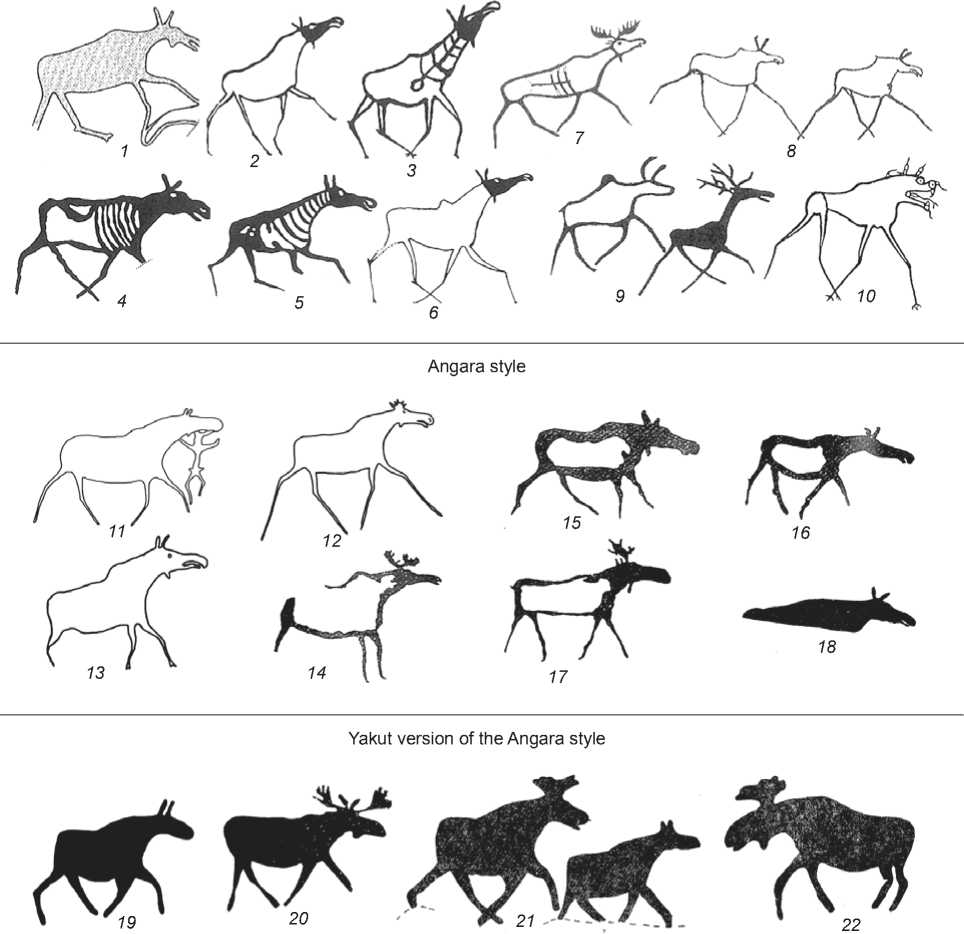

I – Angara style; II – its derivatives; III – Tom style.

1–5 – Kamenny Ostrov II (after (Okladnikov, 1966)); 6 – 8 – Tom rock art site (after (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972)).

The first group (Fig. 2, a ) corresponds to the “naive realistic” style, identified by Okladnikov (Ibid.: 109). These are the earliest images representing the traces of some ancient tradition which preceded the Angara style. Okladnikov attributed them to the Paleolithic. The second group (Fig. 2, b , c ) includes the representations of the so-called Angara style, which is characterized by meticulous attention to details, such as eyes, lips, and neck manes. The third and fourth groups (Fig. 2, d–l) are stylized representations with more angular shapes of bodies, without flowing lines; smaller details are sometimes shown, but rather formally, while the typical hooked nose of the elk is often exaggerated.

Thus, the Angara style in fact breaks up into two chronological layers: the first can be conventionally called “realistic” (Fig 3, 1–3 ), while the second combines two variants of iconography: 1) “stylized”, the main feature of which is representing the head in the form of an amorphous rectangle (Fig. 3, 4 ), and 2) “exaggerated” with an overly large nose and upper lip (Fig. 3, 5 ). The resulting chronological sequence may cause some doubts since the chronological gap between the representations is unknown. However, we can assume that the identified layers belong to various periods, which is confirmed by the circumstantial evidence. Firstly, the upper lip on the small sculpture from the Bazaikha burial ground, which was dated by Studzitskaya to the Chalcolithic, is exaggerated in a similar manner as in the second, later group of the Angara representations of elk. Secondly, traceological analysis of some petroglyphs of the Shalabolino rock art site (Girya et al., 2011) has shown that one figure of elk, which in our opinion is similar to the representations of the “realistic” group, was drawn using a stone implement (Ibid.: Fig. 4), while other representations, executed in the “stylized” manner (the muzzles are shown as rectangles; the legs are outlined in a sketchy way) were made with a metal tool (Ibid.: Fig. 8). From this we can assume that the stylized manner of the “Angara” elk representations is a chronological indicator, and those elk whose muzzles are shown in the form of rectangles without eyes, neck manes, and lips, belong already to the Bronze Age. Since the transition to the Bronze Age was not simply a technological revolution, but also a change of the worldview paradigm, it seems important to distinguish the iconographic groups of “stylized” and “exaggerated” representations from the Angara style, which is characterized by careful rendering of details on the muzzle of elk, such as lips, neck manes, and eyes.

The above analysis makes it possible to define the Angara style in chronological terms in respect to its later derivatives. We should now consider representations attributed to this style in other regions for clarifying its range and for complete description of its iconographic features. About 400 representations were selected; for convenience they were divided by territory: Western

Table 2. Distribution of features identified for the comparative analysis of representations

|

No. |

Features |

Western Siberia |

Okunev |

Shalabolino |

Angara |

Upper Lena |

Yakutia |

|

Total figures |

90 |

7 |

122 |

140 |

12 |

26 |

|

|

1 |

Engraved |

90 |

7 |

119 |

92 |

12 |

– |

|

2 |

Painted |

1 |

– |

3 |

8 |

– |

26 |

|

3 |

Engraved over painted |

– |

– |

– |

35 |

– |

– |

|

4 |

Painted over engraved |

– |

– |

– |

5 |

– |

– |

|

5 |

Ratio 1 : 1 |

30 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

– |

– |

|

6 |

Ratio 2 : 1 |

11 |

– |

77 |

93 |

4 |

26 |

|

7 |

Ratio > 2 : 1 |

1 |

– |

24 |

19 |

6 |

– |

|

8 |

In motion |

32 |

7 |

27 |

40 |

6 |

17 |

|

9 |

Partial |

18 |

– |

20 |

25 |

2 |

– |

|

10 |

Crossed legs |

16 |

5 |

– |

– |

– |

2 |

|

11 |

Narrowed rump |

19 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

– |

1 |

|

12 |

Horns |

– |

2 |

17 |

5 |

4 |

12 |

|

13 |

“Skeletal” representation |

30 |

3 |

8 |

3 |

– |

2 |

|

14 |

Split hooves |

14 |

– |

2 |

3 |

– |

4 |

|

15 |

With two legs or unfinished |

4 |

– |

13 |

27 |

4 |

8 |

|

16 |

Hooked nose / lips / eye |

61 |

6 |

85 |

106 |

3 |

5 |

Siberia (Tom and Tutalskaya rock art sites), Okunev, Shalabolino, the Angara River, the Upper Lena River, and Yakutia (the approximate area of the sites comprises the banks of the Middle Lena and its tributaries as well as the upper reaches of the Amur River). Sixteen features describing the technique and distinguishing features of rendering the animal figures were identified for further iconographic analysis and comparison (Table 2).

Let us first consider the technique (features No. 1–4). It cannot yet be described in more detail due to the nonuniform degree of our knowledge of the monuments. Two main ways of representing the images were found on the Angara: painting and engraving. Sometimes they were combined in various sequences, that is, the image could be engraved and then painted, or vice versa, first painted and then engraved. Such a manner has not been found elsewhere. There are few drawings without engravings. The main part is constituted by images engraved on the rock surface or engraved over the painted representation. There were no clear stylistic distinctions among the figures executed in various techniques. At the Tom, the representations of elk were also engraved. Recent studies have shown that for achieving greater expressiveness, ancient artists combined engraving and polishing (Zotkina, 2010; Miklashevich, 2011). Okladnikov also noted this feature in the Angara petroglyphs (1966: 112). If we turn to the rock art sites of Yakutia, we should note their distinctive feature: all representations, not only of the “Angara” style, were made with paint.

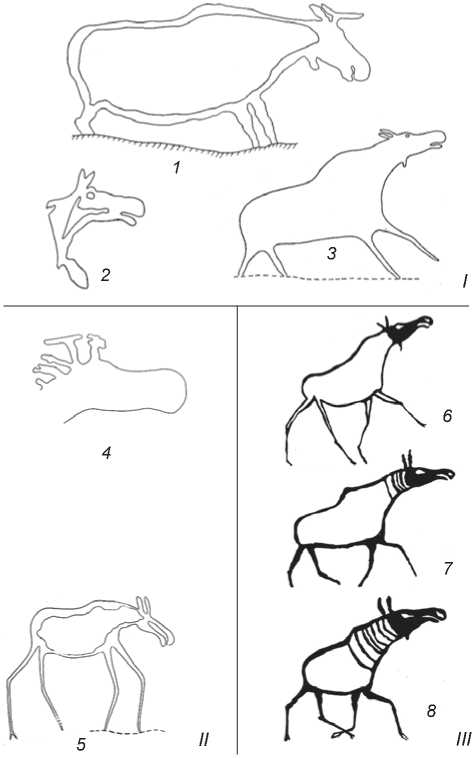

The next group of features (No. 5–7) is associated with the proportions of the animal figure, that is, with the ratio of sizes of the torso and the head. For the Angara elk representations, the ratio of 2 : 1 is typical, and the figure is rendered in a horizontal plane (Fig. 4, 11–13 ). The same is true for elk representations at the Shalabolino (Fig. 4, 14–18 ) and Yakut (Fig. 4, 19–22 ) rock art sites. The Tom petroglyphs have samples with a ratio of 2 : 1 (eleven figures out of ninety) and horizontal configuration, but the main bulk of elk representations differs from the Angara images: the torso is shorter compared to the front part of the body, the neck is heavier, and the ratio of sizes of the head and the body is 1 : 1 (thirty figures out of ninety) (Fig. 4, 1–6 ).

Features No. 8 and 9, which describe the compositional structure of the figure, that is, whether the elk is shown in full, or only the head is represented, and whether it is in motion or standing, are not decisive. The majority of elk representations on the Tom show the animal in a dynamic race, in Yakutia it is shown calmly walking, and on the Angara, considerable variability can be observed: many figures are partial or full; there are images of walking, running, standing, and even flying elk. It appears that the posture of the animal and the partial-/full-figure type of representation are not the style determining features.

Tom style

Fig. 4. Tom style and local versions of the Angara style.

1 , 2 , 4 , 5 – Tom rock art site; 3 , 6 – Tutalskaya rock art site (after (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972)); 7 – Ulus Sartygoi (after (Leontiev, Kapelko, Esin, 2006)); 8 , 9 – Sukhanikha (after (Sovetova, Miklashevich, 1999)); 10 – Tyurya (after (Leontiev, 1978)); 11 , 12 – Bolshaya Kada; 13 – Kamenny Ostrov II (after (Okladnikov, 1966)); 14–18 – Shalabolino (after (Pyatkin, Martynov, 1985)); 19 – Sygdarya;

20 – Sylgylyyr; 21 – Bes-Yurekh; 22 – Yukaan (after (Okladnikov, Mazin, 1979)).

Features No. 10, 11, 13, and 14, which describe the individual elements of iconography (crossed front and rear legs; narrow rump of the animal, “skeletal” type of representation, split hooves), are more typical of the Tom and Okunev images of elk (Fig. 4, 3–10 ). Careful rendering of muzzle details (eyes, lips, and neck manes) is typical both of the Tom and the Angara figures, but not of the Yakut figures, which may possibly be explained by their technique of rendering.

Discussion

The above analysis makes it possible to suggest the following development of the Angara style. The research of Kochmar suggests that this style emerged on the Middle Lena River and its tributaries in the 4th millennium BC. At the same time, it might have also existed in the CisBaikal region. However, the issue of when the Angara style emerged cannot yet be definitively resolved.

The Angara style is an epochal phenomenon with Eastern Siberian roots, and the peak of its development occurred in the Late Neolithic. With the transition to the Bronze Age, the style faded in the East, and the iconography developed in two directions: 1) simplification and stylization (see Fig. 3, 4 ), and 2) exaggeration (Fig. 3, 5 ). New imagery is also associated with the Bronze Age, primarily, the anthropomorphic figures which find their parallels in the pottery of the time (Goriunova, Novikov, 2009). The scholars also attribute the emergence of the boat image to the Bronze Age (Martynov, 1966: 32). Several sites of Eastern Siberia contain combinations of the representations of elk and boat as well as elk and anthropomorphic figure. In the former case, these are stylized representations of elk, the derivatives of the Angara style (Okladnikov, Zaporozhskaya, 1972: Pl. 144), which we dated to the Bronze Age according to the evidence from the Shalabolino rock art site. In the latter case, anthropomorphic figures are overlapped by the representations of elk (Okladnikov, 1966: Pl. 38, 154). This is not obvious in one drawing (Ibid.: Pl. 152), since the description of the figures differs from the presented drawing. Except for isolated cases, the “Angara” compositions include only the images of elk. Thus, the Angara style preceded the rock art layer of the Bronze Age which was characterized by the emergence of different, more sophisticated imagery reflecting the beginning of a new stage.

The influence of the Angara style can be traced far beyond the place where it originated. Stylistic analysis makes it possible to outline its range, which includes the Cis-Baikal region (the Angara and the Upper Lena) and the right bank of the Yenisei (Shalabolino). Yakutia appears to be a province of the Angara tradition: the Yakut version is characterized by the painted manner of representing all images. As for the rest, the Angara style and its Yakut version show common features (see Fig. 4, 11–22 ); primarily, the proportion of elk figures: the ratio of sizes of the head and the torso is 1 : 2. The figures are depicted in a horizontal plane; paired images of elk are often found (see Fig. 4, 21 ). It is important to note that details of the muzzle (eyes, lips, and neck manes) are atypical of the Yakut figures, most likely because of the specific method of rendering: the paint might have blurred with time; in addition, the copying technique could have been imperfect.

The situation with the Tom rock art site is not that simple. Numerous representations of elk which were traditionally referred to as “Angara” include, in our opinion, only several examples of the classic Angara style (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972: Fig. 53, 60, 68, 73, 86, 137).

The results of archaeological research of the second half of the 20th century give grounds to believe that some cultural entity existed in the Late Neolithic in the territory which included the Cis-Baikal region in the east and the Upper Ob region in the west (Anikovich, 1969; Okladnikov, Molodin, 1978). The materials of the Neolithic burial complexes in the northern foothills of the Altai and in the Kuznetsk Depression suggest the migration of population from the east and the inclusion of the eastern component into the Neolithic cultures of these regions. However, the process of interaction between the incoming and the indigenous populations seems to be complex (Kiryushin, Kungurova, Kadikov, 2000: 49, 51–53, 59; Kungurova, 2005: 55; Marochkin, 2014: 153–155). V.V. Bobrov suggested an interesting point that the area of the south of Western Siberia in the Late Neolithic was the contact zone between the cultures of Eastern and Western Siberia (1988).

Scholars have repeatedly noted the participation of the Baikal component in the formation of Neolithic cultures in the south of Western Siberia. Therefore, the presence of the “Angara” component in the pictorial tradition, most clearly represented at the Tom rock art site, can likely be assumed. A large number of distinctive features, atypical of Eastern Siberian representations, make it possible to suggest the development of a particular style in the area. These features include the ratio of sizes of the head and the torso as 1 : 1, and a diagonal arrangement of the figure in the plane, with the head pronouncedly extended upwards at an angle of 45°. The Tom style is characterized by the following features: the “x-ray” type of representation, grounded inner space of the head; depiction of the outstretched legs of the running animal in such a way that one front leg crosses the rear leg, a hump in the form of a small peak, split hooves, narrow rump, and a droplet-shaped nostril (see Fig. 3, 6–8 ).

All these elements are atypical of the iconography of the classic “Angara” elk representations that can be described as follows: the figure is in the horizontal plane, the ratio of sizes of the head and the torso are 1 : 3 or 1 : 4, the hump is smoothly slanting, the lips, the eyes, and the neck mane are shown. The following features vary: paired figures / single / multi-figured compositions, partial / full figures, outlined / silhouette representations, painted / engraved figures, and walking / standing figures (see Fig. 3, 1–3 ).

Thus, the art tradition represented at the monuments of the Tom River should be identified as a distinctive Tom style, with the Angara style acting as a component which influenced the emergence of the Tom style in the very beginning of its formation. The Tom rock art site contains a number of classic “Angara” figures (Okladnikov, Martynov, 1972: Fig. 53, 60, 68, 73, 86, 137), and the classic “Tom” figures primarily inherited the manner of rendering the muzzle of the animal with all the details and elaborated execution. However, a new element, a dropletshaped nostril, was added (see Fig. 4, 2–5 ).

The study of the Angara style would not be complete without considering the rock art of the Okunev culture. Great contribution to the study of this culture was made by N.V. Leontiev (1978), E.B. Vadetskaya (1980), Y.A. Sher (1980), and L.R. Kyzlasov (1986). Scholars have repeatedly noted the availability of the local Neolithic substrate in the Okunev culture (Maksimenkov, 1975: 10; Sokolova, 2009: 167; Savinov, 2006: 160). The assumption about the Neolithic component of the Okunev art is understandable in the context of the fact that the Angara style is regarded as a huge pictorial array which developed over a very long time. Our analysis does not confirm this hypothesis. The “Angara” representations of the elk in the Okunev art show similarities to the “Tom” iconography: crossed front and rear legs, narrow rump, and the “skeletal” type of representation (see Fig. 4, 2–10 ). It is interesting that the famous Okunev figure of a mythical beast follows the line of exactly the “Tom” elk representation. This conclusion does not deny the presence of the Neolithic elements in this culture, but they should be sought in its other components. The Shalabolino rock art site with the classic “Angara” elk representations already reveals Okunev imagery and stylistic features.

The direction of cultural impulses in the Early Bronze Age changed from eastern to western, and the Angara style finished its development. At that time, an assembly of similar cultures of the Okunev circle emerged, and the Tom style developed in their context. Western influence can also be seen in Eastern Siberia. Thus, the set of images in the petroglyphs of the Northern Angara region is associated with the Okunev pictorial tradition (Zaika, 2006). Our conclusion does not contradict the latest studies on the chronology of the Tom rock art site, but rather supplements them. These petroglyphs still hold many mysteries, and one of them is the origins and development of the vivid style of elk representations whose reminiscences can be seen in the art of the later periods. The separation of the Tom and Angara styles, the description of iconographic models for each of them, and the conclusion that the Angara style was a component of the Tom style, make it possible to view the problem of the stylistic origins of the Tom rock art site and specific nature of its interaction with the Eastern Siberian rock art at a different angle.

Conclusions

The Angara style is an epochal phenomenon which made its impact on the artistic traditions to the east and to the west of its origination area. It is a component of the Tom style which should be regarded as a distinct rock art tradition developed already in the context of the cultures of the Bronze Age. The influence of that tradition can be observed in the Okunev art.

The development of the Angara style ended with the beginning of the Bronze Age, when a new pictorial layer emerged in the rock art of Eastern Siberia. New imagery included representations of boats and humans, and some evidence suggests that this area might have been a part of the zone of influence of the Okunev circle of cultures.

This study has managed to solve some key problems of rock art in Eastern Siberia: to identify and describe the actual Angara style and reconsider its interaction with the pictorial traditions of Western and Southern Siberia. Nevertheless, many issues still need to be resolved. Thus, the representations of the Angara style and its Yakut version are dispersed over vast areas of Eastern Siberia; the sites form groups located at a distance of thousands of kilometers between each other. This uneven distribution of sites with stylistically similar imagery cannot be caused only by a similar physical and geographical environment and type of economy, but testify to a sophisticated communication network which existed as early as the Neolithic. Yet it is still a goal of future research to understand how exactly the processes of intercultural communication and cultural transmission over huge distances took place.