On the Philosophical Roots of the Science of Music in the Medieval East

Автор: Agayeva S.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 4 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article focuses on two main musical and philosophical trends that have become widespread in East-ern musical science: cosmological and classical. The study and comparative analysis of many medieval treatises on Eastern music have shown that the science of professional traditional Eastern music did not develop as a single homogeneous stream (as is sometimes mistakenly presented in modern publications), but, like other areas of scientific thought, had different directions. The features of these directions were associated with different, sometimes opposing philosophical views of the authors of the treatises on the origin of music, its purpose and place in human life. The worldviews of these scientists influenced the content of the treatises, the interpretation and method of solving musical-theoretical problems. It is im-portant to note that the mention of the names of outstanding learned musicians of the past in the text of medieval manuscripts is not always an indicator of the continuity of their teachings, nor is it proof of their authorship.

Pythagoras, Aristotle, Farabi, Urmavi, Maraghi, mugham, Azerbaijan

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010584

IDR: 16010584 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.4.24

Текст научной статьи On the Philosophical Roots of the Science of Music in the Medieval East

Various written sources of the ancient and medieval periods indicate that the teachings of ancient Greek thinkers played a major role in the development of the science of Eastern music: Pythagoras and his followers, as well as Plato, Aristotle, Aristoxenus and other thinkers of the ancient world. At the same time, it is known that many ancient Greek philosophers received their education in Egypt, in particular from Egyptian priests [11:182]. For example, Pythagoras (570 - 490 BC), considered the "father" of the science of music, studied for many years in Egypt and Western Asia. There is a claim that "in the land of the pharaohs he studied music" [9:65], and the strong influence of Egyptian musical art on Hellenic is an indisputable fact. However, due to the lack of specific information about that period, it should be recognized that the earliest sources in the field of musical theory for scholars of the Medieval East were the works of ancient philosophers. This fact was noted by the authors of the treatises themselves. An important impetus for the development of the science of music in the Middle Ages was also the translation of the works of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers into Arabic. At the same time, this was not a copying of ancient musical theory. Scholarly musicians of the Muslim East not only adapted the achievements of ancient Greek science to their original musical culture, but also created independent fundamental works reflecting the uniqueness of Eastern musical-theoretical thinking. By the way, we note that in the Middle Ages the opposite process was also observed: many works of Eastern thinkers, in particular Farabi (c. 870-950), Ibn Sina (980-1037) were translated into Latin and became widespread in Europe [10:388390].

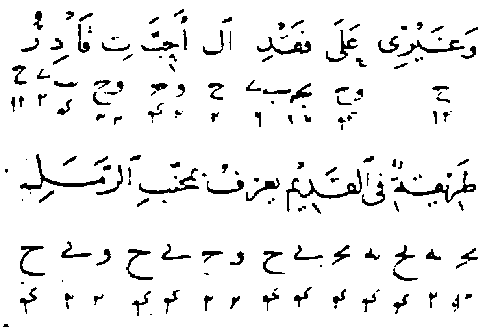

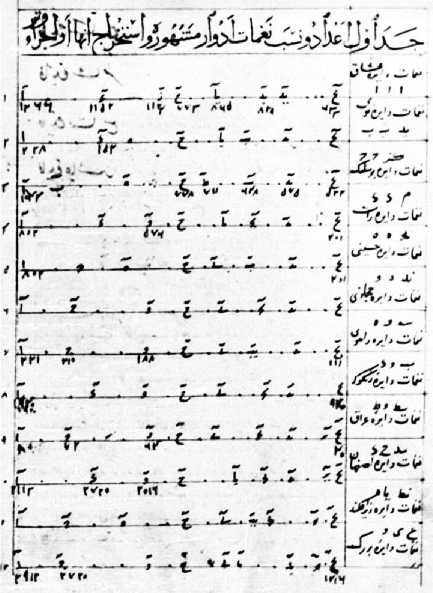

Before moving directly to highlighting the features of the main philosophical trends in the science of music, we note that the object of research by medieval scholars was the professional traditional music of the East, which by the 19th century became known under the general name maqamat (singular maqam/mugam). The art of maqamat, or maqam/mugam art, was formed over many centuries through the efforts of various peoples of the Near and Middle East. An outstanding Azerbaijani scholar and musician of the 13th century, Safiaddin Urmavi, played a major role in the systematization of the numerous modes/maqams that underlie musical works in this vast region and in the development of alphanumeric notation [33; 4:207-209, 16:301-306]. His work was continued by another outstanding Azerbaijani scholar and musician, Abdulgadir Maraghi (1354-1435) [1; 21]. It was in his works that the category of mugham first received a thorough scientific development [3:54-59]. Maraghi, like Urmavi, provides notations of fragments of his own compositions in his treatises. In this regard, an important fact should be noted: despite the fact that the method of training mugham performers was and is largely based on auditory perception and memorization, mugham cannot be unconditionally classified as an art of oral tradition. Many musicians of the Near and Middle East of the 8th-19th centuries, combining the talents of a theoretical scientist and a performing musician, developed and used in practice various methods of graphic recording of traditional makam (mugham) music.

The distinctive features of Azerbaijani mugamat, preserved to this day, are the predominance of improvisational, declamatory-chanting ornamental melody. This metrically free melody unfolds within the framework of certain canons developed over the centuries. However, as the authors of medieval treatises and modern mugamists note, many rules are not so dogmatic. Mugham music contains a certain philosophical message; at all times it has served the function of spiritual perfection for both the listener and the performer. Each mugham has a specific ethos. In the Middle Ages, the methods of healing in the “Houses of Healing” (“Dar ush-Shifa”) and the development of psychology – “the science of the soul” – were associated with listening to traditional musical compositions.

However, it should be taken into account that when comparing the Azerbaijani cyclic mugham with modern makam genres of other peoples, there is often a confusion of concepts, leading to incorrect conclusions [4:8]. A comparison of various types of traditional Eastern music has shown that 1) not all Eastern musical cultures use the term “makam” as a definition of a cyclic genre. In Turkish traditional music, maqam is only a mode, and the cyclic genre is fasıl; 2) not all cyclic genres of traditional music are dominated by improvisation: in the Uzbek-Tajik Shashmaqam, in the Uyghur muqams, and in the Arabic nubas, it is used very limitedly; 3) not every work of an improvisational nature is a multi-part cyclic genre. These include the modern Arabic tagasim, the Turkish taksim, the Turkish folk genre uzun hava, and the Uzbek katta ashule (both meaning "long melody"). In contrast to the listed genres, in the Azerbaijani mugham, modality, improvisation, and cyclicity form an inseparable unity. Azerbaijani mugham has always performed and continues to perform the function of spiritual perfection, influencing “the genetic memory of both performers and listeners, putting them into a trance, immersing and dissolving them in the grandeur and immensity of the harmony of all-unity” [13:266].

The origin and development of mugham as a genre of professional musical creativity is evidenced by various written sources: legends and information based on historical facts. In all cases, the main indicator of professional music composition is the musician's desire to comprehend and classify the music he has created, to fill it with deep philosophical content. One of the confirmations of this is the legend of the mythical bird Simurg (Phoenix, Cacnus, Anka, Humay), known in the medieval East, which is associated with the birth and appearance of Music on earth and the science of music. Some versions of this legend tell of a musician who was enchanted by the singing of this fabulous bird. Based on the sounds he heard, he created 12 makams - the basis for mugham melodies [30; 12:93; 25:82]. It is noteworthy that in the philosophical and didactic, allegorical poem of the Iranian Sufi poet Farid ad-Din Attar (1136-1221) "Mantiq ut-Tayr" ("Conversation of the Birds") and in the treatises on music of subsequent centuries, instead of a musician, a scientist-philosopher is presented, for whom the singing of a fantastic bird served as the basis for the creation of the science of music [27:129-130]. Thus, these works emphasize the original connection of music with philosophy, asserting the version of the simultaneous birth of music both as a phenomenon and as a science of music. One of the main musical-theoretical trends of the medieval East was associated with the cosmological philosophy of Pythagoras. This trend, which became especially widespread in the post-classical period (from the 15th century), included followers of the Pythagorean doctrine of the "harmony of the spheres", in which the origin of music was associated with the movement of the planets and natural phenomena. The harmony of the celestial spheres, according to the Pythagoreans, gave rise to the earthly sound harmony, in which the distance between sounds, as well as between planets, was determined by mathematical calculations, since number (in a broad and symbolic sense) was considered the beginning of all things. In the Pythagorean teaching, the cosmological beginning was paradoxically combined with specific mathematical calculations: by dividing the string of a monochord, the location of the steps of the diatonic scale was determined.

The followers of the Pythagoreans in the eastern music of the Middle Ages recognized and developed only the cosmological direction of this teaching and showed no interest in its mathematical side. This was reflected in the content and character of their treatises: with rare exceptions (for example, the works of al-Kindi), they lacked mathematical calculations and digital notations of intervals. In addition to al-Kindi (10th century), the adherents of cosmological views were the representatives of the secret religion and the scientific-philosophical society “Brotherhood of Purity” (“Ikhwan al-Safa”, 10th century, city of Basra), M. Nishapuri, as-Safadi, and in the post-classical period - Yusif Kirshehri, Bedr Dil'shad, M. Ladiqi, Abdulmomin bin Safi ad-Din (author of the treatise "Behjat ul-ruh", 17th century) [22], Dervish Ali Changi [19], Mirzabey (17th century) [14], anonymous authors of the treatises "Rukhperver", "Advar" [2] and others. The exposition of makam theory in these works is descriptive in nature and is basically reduced to a list of the names of tones - frets on the oud string (desatin, parde) included in the compositions; but the pitch of these tones was not indicated. The texts in these treatises are replete with retellings of legends and parables on religious themes, many of which are cited to confirm the pleasingness of music to God. Despite the presence of interesting facts for the history of music concerning musical instruments and musical forms, much of the historical information in these works is replete with anachronisms and does not correspond to the actual biographical facts from the lives of great learned musicians of the past. In these treatises, the creation of certain instruments and musical works is unjustifiably attributed to various characters from legends, prophets and angels, religious figures, famous scientists and historical figures. It was believed that such "facts" give "weight" to the work and the author, and also help to justify to the ministers of orthodox Islam the permissibility of music. In this regard, references to treatises on music by Dervish Ali Changi, "Behjet ul-Rukh", "Rukhperver" and other works of the late medieval period of the cosmological direction, regarding any musical-historical events, cannot be considered scientifically reliable.

The origin and development of mugham as a genre of professional musical creativity is evidenced by various written sources: legends and information based on historical facts. In all cases, the main indicator of professional music composition is the musician's desire to comprehend and classify the music he has created, to fill it with deep philosophical content. One of the confirmations of this is the legend of the mythical bird Simurg (Phoenix, Cacnus, Anka, Humay), known in the medieval East, which is associated with the birth and appearance of Music on earth and the science of music. Some versions of this legend tell of a musician who was enchanted by the singing of this fabulous bird. Based on the sounds he heard, he created 12 makams - the basis for mugham melodies [30; 12:93; 25:82]. It is noteworthy that in the philosophical and didactic, allegorical poem of the Iranian Sufi poet Farid ad-Din Attar (1136-1221) "Mantiq ut-Tayr" ("Conversation of the Birds") and in the treatises on music of subsequent centuries, instead of a musician, a scientist-philosopher is presented, for whom the singing of a fantastic bird served as the basis for the creation of the science of music [27:129-130]. Thus, these works emphasize the original connection of music with philosophy, asserting the version of the simultaneous birth of music both as a phenomenon and as a science of music. One of the main musical-theoretical trends of the medieval East was associated with the cosmological philosophy of Pythagoras. This trend, which became especially widespread in the post-classical period (from the 15th century), included followers of the Pythagorean doctrine of the "harmony of the spheres", in which the origin of music was associated with the movement of the planets and natural phenomena. The harmony of the celestial spheres, according to the Pythagoreans, gave rise to the earthly sound harmony, in which the distance between sounds, as well as between planets, was determined by mathematical calculations, since number (in a broad and symbolic sense) was considered the beginning of all things. In the Pythagorean teaching, the cosmological beginning was paradoxically combined with specific mathematical calculations: by dividing the string of a monochord, the location of the steps of the diatonic scale was determined.

The followers of the Pythagoreans in the eastern music of the Middle Ages recognized and developed only the cosmological direction of this teaching and showed no interest in its mathematical side. This was reflected in the content and character of their treatises: with rare exceptions (for example, the works of al-Kindi), they lacked mathematical calculations and digital notations of intervals. In addition to al-Kindi (10th century), the adherents of cosmological views were representatives of the secret religious and scientific-philosophical society "Brothers of Purity" ("Ikhwan al-safa", 10th century, city of Basra), M. Ni-shapuri, as-Safadi, and in the post-classical period - Yusif Kirshehri, Bedr Dilshad, M. Ladiqi, Abdul-momin bin Safiaddin (author of the treatise "Behjat ul-ruh", 17th century) [22], Dervish Ali Changi [19], Mirzabey (17th century) [14]. anonymous authors of the treatises "Rukhperver", "Advar" [2] and others. The presentation of maqam theory in these works is descriptive in nature and is mainly reduced to a list of the names of tones - frets on the oud string (desatin, parde), included in the compositions; but the pitch of these tones was not indicated. The texts in these treatises are replete with retellings of legends and parables on religious themes, many of which are cited to confirm the pleasingness of music to God. Despite the presence of interesting facts for the history of music concerning musical instruments and musical forms, much of the historical information in these works is replete with anachronisms and does not correspond to the actual biographical facts from the lives of great learned musicians of the past. In these treatises, the creation of certain instruments and musical works is unjustifiably attributed to various characters from legends, prophets and angels, religious figures, famous scientists and historical figures. It was believed that such "facts" give "weight" to the work and the author, and also help to justify to the ministers of orthodox Islam the permissibility of music. In this regard, references to treatises on music by Dervish Ali Changi, "Behjet ul-Rukh", "Rukhperver" and other works of the late medieval period of the cosmological direction, regarding any musical-historical events, cannot be considered scientifically reliable.

At the forefront of classical musical theory was the scientific, physical explanation of the origin of sound and mathematical calculations concerning the pitch complex of professional music. The ideas of Aristotle's follower Aristotle were also reflected in the works of classical theorists. Although these learned musicians of the medieval East, unlike Aristoxenus, did not deny the stability of the relationship of the main Pythagorean intervals (octave, fourth, fifth) and used mathematical calculations to find the basic scales, what was important for them (following Aristoxenus) was the "authority of hearing", which was decisive for determining the basic complex of tones of traditional makam-mugham music. Having combined the Pythagorean scale with the natural scale of Aristoxenus, using the theoretical research of Farabi and Ibn Sina, as well as his own scientific and musical-practical experience, Safiaddin Urmavi developed a universal scale for professional music of the Near and Middle East. At the same time, the main criterion for selecting the basic sound composition of the modes (makams, avaz in Urmavi and shobe in Maragha) was their euphony in practical performance. It should be noted that in his first work, Kitab al-advar (The Book of Cycles/Periods), which marked a radical turn in the science of music, Safiaddin Urmavi does not mention ancient Greek philosophers. Urmavi’s direct scientific sources were the works of Farabi and Ibn Sina. At the same time, the Azerbaijani scientist does not accept their judgments unconditionally, and corrects their formulations of sound, melody, and rhythm. Only at the beginning of his second treatise, Sharafiyya, does Safiaddin Urmavi, after a short traditional “bismillah,” note: “This treatise ‘On the Science of Relationships in Composition’ is written on the basis of [the method] laid down by the ancient Greek sages. However, it has been supplemented [by me] with much useful knowledge that is absent both in their works and in the works of subsequent authors” [18; 26:99.65; 17:317]. It seems that the mention of ancient Greek scholars in this case is rather a formal tribute to distant predecessors. It is also possible that the educational and upbringing function of this treatise played a role here: after all, Safiaddin Urmavi wrote this work for his student, Sharafaddin Harun Juvayni, as evidenced by the title of the treatise and the dedication preceding the main text.

The study of the philosophical roots of treatises on music makes it possible to determine not only the scientific direction, but also the authorship of a particular work. In various modern publications, the anonymous treatise "Kitab-i advar" (another name "Rukhperver"), written in the Turkic language (library of the University of Leiden, Holland, Or. 1175), was mistakenly included in the list of musical and theoretical works of Abdulgadir Maragha. A comparative analysis of the manuscripts showed that this treatise does not belong to Maragha. This was revealed not only on the basis of the complete difference in the factual material. The treatise “Kitab-i advar” (“Rukhperver”) belongs to a completely different, “cosmological” branch of science, which contradicts the philosophical worldview of Abdulgadir Maragha.

One of the similarities between the classical and cosmological schools was the interest of the authors of the treatises in the problems of the ethos of music, its healing and educational qualities. But representatives of different worldviews also covered this problem differently. One of the main goals of the teachings of the "Brothers of Purity" was to promote the education of a virtuous person. This work notes the ability of music to influence human emotions and improve his moral qualities. According to the authors, it was the combination of excellent human qualities, purity of soul and insight of mind that allowed Pythagoras to develop the foundations of music [15:271]. Indications of the healing and educational value of music are contained in the "Treatise on the Soul" ("Risala fi-n-nafs") and the treatise "Divisions between Wisdom and Sciences" ("Taqasim al-hikma wa-l-ulum") by Ibn Sina. Some chapters of many treatises of the medieval East are devoted to the same topic, but in varying volumes. It should be emphasized that the practicing musician of the past centuries, as well as the modern mugham performer, was attracted and interested in music not only (or even not so much) from the philosophical point of view of comprehending the "Inaudible Euphonies", but also as a universal opportunity to receive earthly pleasure, aesthetic enjoyment. This property of musical art was recognized by many Pythagoreans - adherents of the rational, "reasonable" perception of music, and the authors of the classical direction of the science of music of the medieval East wrote about it.

The definition of scientific and philosophical trends and directions of the studied treatises is necessary for the correct, objective coverage of the process of development of the science of music. Knowledge of the specifics of scientific trends in music theory and a comparative analysis of primary sources - manuscripts of treatises - allows us to avoid distorting the history of mugham art and musical culture in general.

Fig. 1. A fragment of a musical work by Safiaddin Urmavi (13th century), recorded in the alphanumeric system "abjad"

Fig. 2. Mugham scales in the treatise "Jame al-alkhan" by Abdulgadir Maraghi (14th-15th centuries)

Fig. 3. Treatise on music by Hashim Bey (19th century).

Scheme of the influence of mugham and elements of nature on man