On the time and context of the earliest bronze mirrors in the Northern Pontic region

Автор: Kuznetsova T.M.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145400

IDR: 145145400 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.4.059-066

Текст обзорной статьи On the time and context of the earliest bronze mirrors in the Northern Pontic region

Studies into the material and spiritual culture of the Scythians, as well as clarification of the time and nature of their relationship with other peoples, are conducted using archaeological and written sources. The dates of archaeological sites are established from the items that are a part of the accompanying inventory and serve as chronological markers, among which are mirrors.

The archaeological materials of the Kelermes cemetery form the basis for determining the duration of the Early Scythian stage in the history of the Northern Black Sea region and the North Caucasus, since they can be correlated with written sources that reflect the events associated with the stay of the Scythians on the territory of Western Asia. Earlier, the date of Kelermes was based on the written sources (first half of the 6th century BC), and the date of the material complex associated with the Middle East only confirmed it (Iessen, 1953: 49; Maksimova, 1954; Artamonov, 1974: 57).

The emergence of a series of chronological definitions pushed the date of the Archaic Scythian period to an earlier time (Kossack, 1987; Medvedskaya, 1992), which caused discrepancies between archaeological and narrative sources. After research, the previously established date of the Kelermes cemetery was revised,

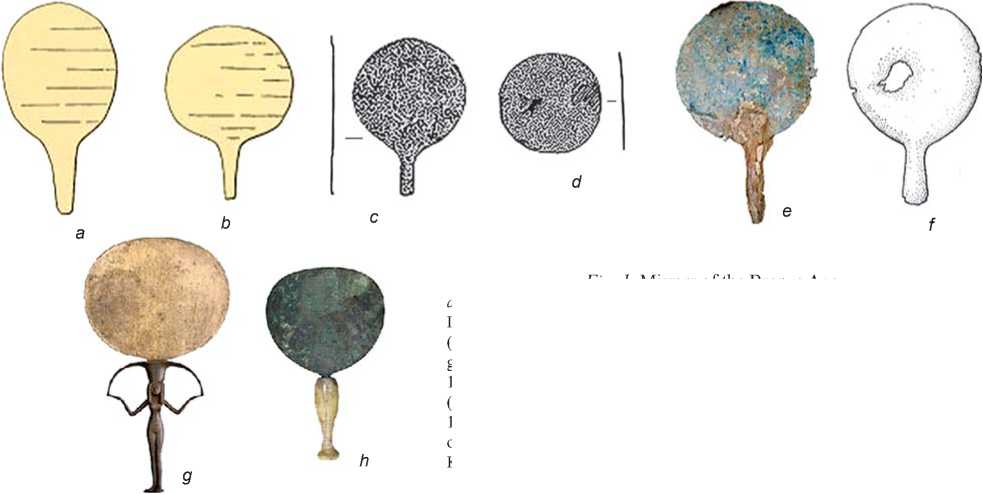

Fig. 1. Mirrors of the Bronze Age.

a, b – Ur (after (Woolley, 1934a: pl. 230, N U 114534, U 11484)); c, d – Gissar III (after (Schmidt, 1937: 422, 456, pl. LIV, N H. 3192; H. 4872)); e – Pilos (after (URL: (accessed November 10, 2016))); f – cemetery near the village of Kara-Pichok (Gissar Valley) (after (Vinogradova, Kuzmina, 1986: 137, fig. 6, 3)); g – Egypt, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty: 1550–1295 BC (after (URL: opencollection/objects/4068 (accessed November 10, 2016))); h – Egypt, New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty (after (URL: collections/antiquities/ancient-egypt/ (accessed November 10, 2016))).

since one of the most important chronological indicators of the Archaic Scythian period was the Kelermes silver “mirror” (?), which was found in kurgan 3 (?) or 4 (?), excavated by D.G. Schultz (Galanina, 1997: 190–191). The date of this specimen (580–570 BC) initially only supported the established time when the cemetery functioned (Maksimova, 1954), yet after its revision to an earlier time (670–640 BC) it became one of the decisive chronological benchmarks (second half of the 7th century BC) (Kisel, 2003: 99; Alekseev, 2015: 90, nt. 3). However, that silver article from the Kelermes cemetery has not been clearly identified as a mirror, and the time and place of its manufacturing have not been established (Maksimova, 1954; Kisel, 1993: 125; 2003: 99; Vakhtina, 2010: 103), thus it cannot serve as a marker for dating.

The new, earlier dates of the sites of the Archaic Scythian period became the cause of many contradictions. One of them is associated with establishing the time when bronze mirrors with side-handles appeared in the Northern Pontic region: in the studies, the side-handle assumed the role of a dating indicator (Vakhtina, Kashuba, 2016: 42–43, 47). However, the presence of the side-handle cannot be a dating feature for Archaic Scythian sites, since mirrors with such handles existed both in the previous and subsequent periods of time.

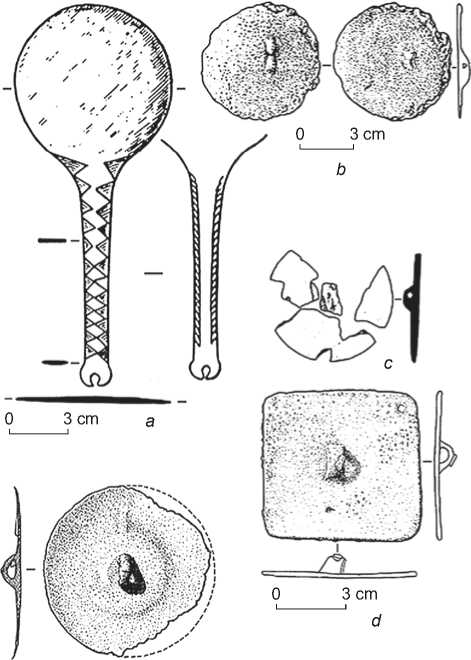

According to the majority of scholars, bronze mirrors appeared in Mesopotamia and Northern Iran in the third–second millennium BC (Chlenova, 1967: 89), although identification of some specimens as mirrors (Fig. 1, a, b) raised doubts among scholars (Woolley, 1934a: 310), who admitted that the articles under consideration (Fig. 1, c, d) could have been both covers or fans (Schmidt, 1937: 422, 456, pl. LIV). During the Bronze Age (third–second millennium BC), mirrors were used not only in Mesopotamia (Albenda, 1985: 2–3), but also in Egypt (Brunton, 1927: Pl. XXXIX; William, 1978: Ill. 1: 241; Ill. 2: 63–64), the Mediterranean (Keene Congdon, 1985: 19; Strøm, 1998: 75), Central Asia (Kuz’mina, Vinogradova, 1983: 101, Ill. 8, 16), and Siberia (Chlenova, 1967: 90; Tishkin, Seregin, 2013). At that time, as a result of contacts between the populations of various regions, bronze mirrors, which had specific local features of configuration and design of the disk and handle, became widespread over a vast territory. Round disks of mirrors were typical of the Mediterranean in the Mycenaean period (Fig. 1, e). In Egypt, the disks had the shapes either of an ellipse stretched horizontally (Fig. 1, g), or of an inverted pear (Fig. 1, h). Predominantly composite mirrors with a side-handle made of various materials or with bases in the form of various figures have been found on these territories. One-piece mirrors with a side-handle (Fig. 1, c, f) and with the disc slightly extended vertically have been discovered in Western and Central Asia. A variety of mirror shapes with a central or side-handle (Fig. 2) have been found at the sites of the Bronze Age in Siberia (Tishkin, Seregin, 2013). Thus, it can be concluded that mirrors with a side-handle were used from a very early period.

Neither “imported” mirrors nor local production centers of these items in the Bronze Age have been found in the Northern Black Sea region and the North Caucasus. Bronze mirrors in these regions could have appeared only at the end of the 7th century BC, after the arrival of the people whom the Persians called the Saka, and whom the Greeks called the Scythians, from the eastern part of Eurasia (Herod. VII, 64)*.

Scythian and Greek traditions in the Northern Black Sea region

It has not yet been possible to identify Scythian sites with mirrors, belonging to the 7th century BC, in Eastern Europe. Bronze mirrors started to appear in burial mounds of this region in the second quarter of the 6th century BC, which can be explained by the return of the Scythians from Western Asia (the “post-campaign” time) and the activities of the Greeks—the inhabitants of the Northern Black Sea colonies.

“Scythian” (one-piece) mirrors look like a disk with a rim and central loop-handle, cast together (Fig. 3, a , b ). The origin of such mirrors is associated with Central Asia (Chlenova, 1967: 90) or Siberia (Smirnov, 1964: 155). The sites located in the eastern part of Eurasia where such mirrors have been found, show earlier dates than archaeological complexes containing items of similar appearance, but originating from the territory of the Northern Black Sea region. Three such mirrors of the 8th century BC, which were found in China, are

0 3 cm

Fig. 2 . Mirrors from the sites of the Late Bronze Age in Siberia (the Upper Ob region).

a – Kamyshenka (after (Chlenova, 1981: Fig. 2, 1)); b – Rublevo VI;

c – Chekanovsky Log-7; d – Rublevo VIII; e – Malyi Gonbinskiy Kordon I, cemetery 5 (after (Tishkin, Seregin, 2013: 117, fig. 1)).

considered to be the result of foreign cultural impact from nearby areas (Varenov, 1985: 166–167). Mirrors of this type found on territories adjacent to China date to a later time: 7th–6th or 6th–5th centuries BC (Kiryushin, Tishkin, 1997: 88; Mogilnikov, 1997: 81; Varenov, 1999: Fig. 1, 6 ; Shulga, 2010: 44–46, fig. 30, 11 ; 81, 6–8 ).

The sites of occurrence of “Scythian” mirrors on the territory of Eurasia seem to correspond to movement routes of individual groups of the nomadic population from the Aral Sea region in the eastern and western directions. Subsequently, the nomads headed from Siberia to the west. Such migrations must have occurred more than once in the late 7th–6th centuries BC (Kuznetsova, 2016a). There is an alternative point of view, according to which “Scythian” mirrors first penetrated the Altai and the territory of Kazakhstan from China, and then spread to the west (Chlenova, 1967: 82). Specialists have observed that archaic mirrors were massive, while in the second half of the first millennium BC mirrors show a tendency to decrease in size, although there are exceptions (Kiryushin, Tishkin, 1997: 88; Tishkin, Seregin, 2011: 94–95), and it is

m

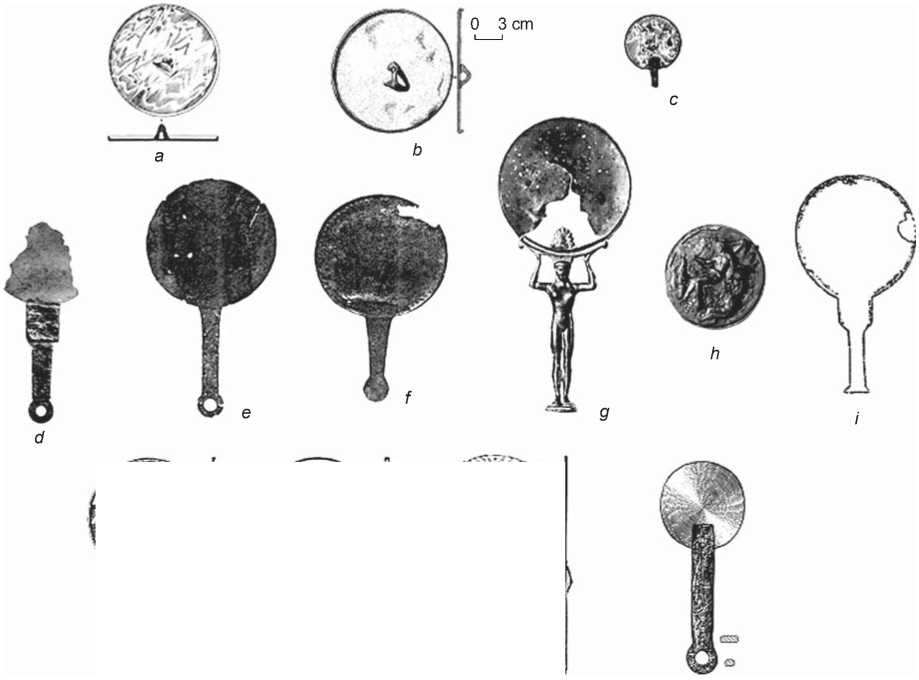

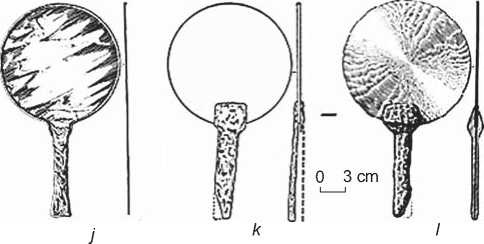

Fig. 3 . “Scythian” ( a – c ) and Greek mirrors ( d – i ), imitations of Greek mirrors ( j–m ).

a – village of Zhurovka, kurgan No. 407 (after (Kuznetsova, 2002: Pl. 12, No. 195)); b – Malyi Gonbinskiy Kordon I, cemetery 1, grave 28 (after (Tishkin, Seregin, 2011: Pl. 1, 3 )); c – burial mound of “Zakhareikova Mogila”, burial 1 (after (Kuznetsova, 2002: Pl. 76, No. 201)); d – necropolis of Olbia, grave 23 (after (Skudnova, 1988: 58–59, cat. 62)); e – necropolis of Olbia, grave 4 (after (Bilimovich, 1976: Fig. 3)); f – necropolis of Olbia, grave 7 (after (Ibid.: Fig. 7, cat. 66)); g – village of Annovka (after (Onaiko, 1966: Pl. XIX, 5)); h – necropolis of Panticapaeum (after (Trofimova, 2007: 181, cat. No. 163)); i – Corinth (after (Payne, 1931: 228, fig. 103, A )); j – burial mound of “Repyakhovataya Mogila”, tomb No. 2 (after (Kuznetsova, 2002: Pl. 29/Б, No. 477))*; k, l – burial mound of “Repyakhovataya Mogila”, tomb No. 2 (after (Ilyinskaya, Mozolevsky, Terenozhkin, 1980: Fig. 20 (image of the mirror after excavation); Kuznetsova, 2010: Pl. 86, No. 476 (image of the mirror as it was in 1985))); m – cemetery of Nartan, kurgan No. 20 (after (Kuznetsova, 2010: 29, pl. 17, No. 353)).

impossible to disagree with that observation. The highest concentration of massive mirrors was found in the burial grounds of the Southern Aral Sea region (Vishnevskaya, 1973: 84–85; Itina, Yablonsky, 1997: 42–43).

Although the mirrors of that type found in China are dated to an early period, they are small. The question of how such mirrors arrived to this territory still remains open.

S.V. Makhortykh (2016) suggested a new hypothesis concerning the occurrence of the mirrors under consideration in Eastern Europe. Adding information on the recent finds from the Dnieper forest-steppe region and North Caucasus to available evidence on such items, Makhortykh distributed them into groups in accordance

*There was a typo in plate 29/Б (No. 474 was printed).

with the types mentioned above, which differed by the shape of the loop, and determined the areas with the highest concentration of “Scythian” mirrors of each type. According to Makhortykh, the variant with the triangular loop-handle (Fig. 3, a ) was of local Eastern European origin and the latest modification of the items under consideration (Ibid.: 313). Unfortunately, the scholar did not take into account the results of the metal analysis, which indicated that all “Scythian” mirrors were cast from tin-arsenic bronzes, which, according to their chemical features, were similar to the Mongolian and Northern Caucasian metalwork of the Scythian period (Bartseva, 1981: 65; Olgovsky, 1990: 105).

Mirrors with a triangular loop-handle have also been found in east Eurasia: in the Arzhan-2 burial mound in Tuva (Kuznetsova, 2010: 233, fig. 39) and in grave 28

of cemetery 1 at the Maly Gonbinskiy Kordon I site, on the right bank of the Ob River (the Upper Ob region) (Tishkin, Seregin, 2011: 26, pl. 1). In the find from the latter site (Fig. 3, b ), the disk and handle were made of metals which had various compositions. The mirror was probably repaired: scholars have observed that the loop-handle was made separately and then was probably soldered to the disk (Ibid.: 66). This specimen of the late 7th–6th centuries BC confirms that the tradition of making mirrors with a central loop-handle in Siberia, which went back to the Bronze Age, made it possible to repair an item without deforming the disk, which was not the case with the tradition in the Northern Black Sea region.

In Eastern Europe, the “Scythian” mirrors were repaired in a different way, which led to changes in their structural design. Composite mirrors with two handles have been found at the sites of the 6th century BC, including a burial near the village of Lenkovtsy in Podnestrovye (Melyukova, 1953: 64, fig. 28) and burial 1 at “Zakhareikova Mogila” (Fig. 3, c ), on the right bank of the Dnieper (Ilyinskaya, Mozolevsky, Terenozhkin, 1980: 59, fig. 36). Here, owing to the breaking off of the central handle (or for some other reason), a side-handle made of iron was attached to the disk.

Mirrors with a central loop-handle appeared almost simultaneously with mirrors having a side-handle at the Scythian sites of the Northern Pontic region (Kuznetsova, 2002: 141; 2010: 236–238). Since there was no local tradition of manufacturing mirrors in the Northern Black Sea region, the replacement of a central handle with a side-handle on the “Scythian” mirrors, as well as the appearance of new forms with side-handles, can be explained by contacts with the Greek population. All changes in shape and structure (Fig. 3, d , h ) of Ancient Greek models are reflected at the sites of this region (Bilimovich, 1976).

The archaic mirrors of Greece are represented by flat one-piece forms with side-handles (Fig. 3, d , f ). According to scholars, the centers of their manufacture were Corinth, Argos, and Sparta. Such mirrors appeared on the territory of Greece not earlier than the 6th century BC (Ibid.: 38–43)*.

Greek mirrors of the “Corinthian” type in the Northern Black Sea region were discovered on the Kerch Peninsula in tomb No. 4, dated to the second half of the 6th century BC, at the cemetery near the village of Zolotoye (Maslennikov, 1980: 90, fig. 1, 1), and in grave No. 23, dated to the late 6th century BC, at the Olbia necropolis (Skudnova, 1988: 58).

Round discs were typical, and handles made of iron were untypical for early Greek mirrors, which makes it possible to consider the Northern Pontic forest-steppe region as one of the possible areas for the emergence of the tradition of replacing the handle in mirrors, as well as the appearance of imitations of Ancient Greek models. Two such mirrors with side-handles were found in tomb No. 2 at “Repyakhovataya Mogila”, pertaining to the Archaic Scythian period, in the forest-steppe zone on the right bank of the Dnieper (Fig. 3, j–l ). They are similar to the Greek mirrors of the “Corinthian” forms (Fig. 3, d , i ); therefore, they have been dated to no earlier than the second quarter of the 6th century BC (Kuznetsova, 2017), since their prototypes appeared in Greece around that time (Oberländer, 1967: 5). Imitations of Ancient Greek mirrors have also been found in the North Caucasus. The iron side-handle of a composite mirror (Fig. 3, m ) from kurgan No. 20 of the Nartan cemetery is similar to the handles of the “Argos” mirrors (Fig. 3, e ), known from the Northern Black Sea region (Olbia necropolis, grave No. 4—the 530s BC (Skudnova, 1988: 70)). It does not make it possible to date kurgan No. 20 at Nartan to a period earlier than the second quarter of the 6th century BC, associated with the appearance of such mirrors in Greece (Oberländer, 1967: 5; Bilimovich, 1976: 33).

Since such mirrors have prototypes in certain centers of Greece, they may serve as markers for dating archaeological complexes.

Problems of dating

In terms of time (second quarter–mid 6th century BC), the burial mound of “Repyakhovataya Mogila” corresponds to the return of the Scythian army of King Madius from his campaign in Western Asia. This is confirmed by the presence of Transcaucasian (Urartian) beads in tomb No. 1 of that site (Ryabkova, 2010: 179), and a bronze krater of Transcaucasian (Urartian) origin in tomb No. 2 (Olgovsky, 1987).

The similarity between the accompanying goods from the tombs of “Repyakhovataya Mogila” and Kelermes according to ten categories makes it possible to attribute the latter to the time “after the campaign”—the period of not earlier than the last decade of the first quarter of the 6th century BC (Kuznetsova, 2016b: 85–87). This definition does not contradict the written sources, according to which the expulsion of the Scythians from the Middle East happened after 585 BC, and serves as a basis for the claim that the date of the Archaic Scythian sites has been unjustifiably set too early.

Considering the shape of mirrors from tomb No. 2 of “Repyakhovataya Mogila”, Scythian sites cannot be dated to the 7th century BC, but their creation occurred in a period of not earlier than the second quarter of the 6th century BC. Therefore, the problem of the appearance of mirrors with a side-handle in the Northern Pontic region was further addressed in connection with identification of a bronze handle from the Nemirov fortified settlement (located on the left bank of the Yuzhny Bug River) as a chronological indicator for the Scythian culture of the 7th century BC (Kașuba, Vakhtina, 2016: 268).

As far as the Nemirov handle is concerned, scholars have not succeeded in finding its place among other mirrors, and in precisely establishing the center of its manufacture; they only hypothetically attributed this specimen as being a product made by a Greek artisan. Despite of all this, they declared that the find was a “chronological indicator of the Scythian type”, and proposed to move the dates of some mirrors from the forest-steppe Scythia to an earlier period (Ibid.; Vakhtina, Kashuba, 2016). However, an item that does not have an exact attribution* cannot serve as a chronological benchmark for the Scythian sites. Importantly, the presence of only a side-handle should not be considered as a chronological attribute, since mirrors with side-handles have been known from various regions starting in the Bronze Age. Exactly for that reason, sidehandles of mirrors cannot be chronological markers as follows from some works on Scythian archaeology (Medvedskaya, 1992: 91; Daragan, 2010: 191; Kașuba, Vakhtina, 2016: 272; Vakhtina, Kashuba, 2016: 42, 47). The date of a particular mirror, as a rule, is established by specialists based on specific features of both the disk and the handle. Owing to the distinctiveness of Greek archaic mirrors, including their imitations, the sites in the Northern Black Sea region cannot be dated to a period earlier than the 6th century BC (according to the time when similar items appeared in Greece).

Conclusions

In the 6th century BC, the Northern Pontic region was a contact zone for three cultural entities: the autochthonous population, the Scythians, and the Greeks. Both “Scythian” and Greek mirrors turned out to be an innovation in the culture of the local population. The Scythians were apparently the only carriers of the tradition of using mirrors with a rim and central looped handle. The Scythians were unable to pass the skill of making such products on to the Northern Black Sea artisans of bronze casting, and the tradition in this region faded away by the 5th century BC. Scholars have also

*A handle from Nemirov could have belonged to a vessel close in shape to an Ancient Greek patera.

noted the disappearance of the items in question in the 5th century BC in the east of Eurasia (Kiryushin, Tishkin, 1997: 89; Tishkin, Seregin, 2011: 91). Thus, we may assume that in the 6th century BC the Scythians left the areas where the artisans worked who produced for them special forms of mirrors, since in the 6th–4th centuries BC traditional forms of mirrors with a central loop-handle but without a rim continued to exist in the eastern regions (Kiryushin, Stepanova, 2004: 80–81).

When mirrors entered a foreign cultural environment, they might have preserved their features for a long time. Chinese mirrors with a central handle, distinguished by their exquisite decoration on disks, have been known for a long time since the 4th century BC on the vast territory from Primorye and Siberia to the Volga region and the Northern Black Sea region (Lubo-Lesnichenko, 1975: 6–11; Oborin, Savosin, 2017: 2–6). In the Altai and Ural regions, at the sites of the 5th–2nd centuries BC, mirrors with side-handles and relief ornamentation on the disk have been found. Scholars view these mirrors, like other mirrors similar in disk design, as simplified versions and imitations of rattle mirrors* found in the same regions (for bibliography see (Treister, 2012)). Egyptian mirrors of the 7th century BC with side-handles and bases have been found in the burial of a nomad of the 5th–4th centuries BC in the Southern Urals (Ibid.: 120–121, fig. 62) and in Archaic Greece (Payne, 1940: 142–143, pl. 46).

Mirrors reached the Greek colonies of the Northern Pontic region starting in the 6th century BC from various centers of the Mediterranean. The contacts of the colonists with the local population, which apparently included “metallurgists”, triggered the appearance of not only mirrors typical of Greece, but also the imitations of Ancient Greek models on this territory starting in the second quarter of the 6th century BC.