Personality Predictors of Flourishing and Learning to Flourish

Автор: Margarita Bakracheva

Журнал: International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science, Engineering and Education @ijcrsee

Рубрика: Original research

Статья в выпуске: 1 vol.13, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Given the abundance of research on well-being and flourishing, this study aimed to outline the direct and indirect effects of personality predictors on flourishing. The cross-sectional study included ten scales, measuring personality traits (the extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, consciousness, agreeableness and the meta-traits of plasticity and stability) and personal dispositions (self-esteem, mindfulness, coping and coping potential, learned helplessness, self-handicapping, planning, and rumination) and a convenient sample of 451 respondents. A ten-session training designed to promote flourishing was conducted with 10 participants over a three-month period. Results revealed a stronger direct effect of personal dispositions than personality traits, as well as a moderating effect of personality traits and a mediating effect of dispositions. Flourishing is predicted by high self-esteem, proactive coping, mindfulness, agreeableness, and meaning in life. Problem-oriented coping mediates the relation of agreeableness and flourishing. Conscientiousness and stability moderate the relation of proactive coping and mind-fulness with flourishing, and plasticity moderates the relation of self-esteem and flourishing. This finding is considered to highlight the specific role of plasticity and stability both as traits and dispositions, related to self-regulation. Self-esteem needs to be flexible enough to be revised and validated and is supported by plasticity, while proactive coping and mindfulness, as dispositions related to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects, are supported by stability. Flourishing is predicted to a greater extent by behavioural patterns than by personality traits, and the pathways to flourishing can be learned, which is of particular interest for integration in education as proactive support for individual performance, especially in times of crisis and instability.

Flourishing, personality traits, mindfulness, coping

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/170209051

IDR: 170209051 | УДК: 159.923.3.072 | DOI: 10.23947/2334-8496-2025-13-1-141-156

Текст научной статьи Personality Predictors of Flourishing and Learning to Flourish

© 2025 by the authors. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license .

relationships, mental and physical health ( Turecek et al., 2024 ) and connection to something larger than the self ( Seligman, 2011 ). According to VanderWeele (2017) , flourishing is associated with optimal functioning in five broad domains: (i) happiness and life satisfaction; (ii) health, both mental and physical; (iii) meaning and purpose; (iv) character and virtue; and (v) close social relationships across two criteria: as a desirable goal and as universally desirable goals, considering not only the present moment but also in a temporal perspective - a perceived secure environment, including financial and social stability, in order to flourish over time ( VanderWeele, 2017 ).

Flourishing is considered to be a multidimensional concept. Numerous cross-cultural comparisons have been conducted, as well as qualitative research on respondents’ perceptions and what they believe they need to flourish, and various studies have ranked social support, stable income, and social determinants of health as the most important factors; meaningful work, identity, and family are also widely ranked by respondents. The wide range of responses and included domains leads to the suggestion well-being and flourishing to be viewed as multidimensional constructs ( Burns et al., 2025 ). In a similar direction is the proposed expansion of the concept of positive well-being, accounting for relationship, parenting, and employment, which are reported to have more significant effect on well-being than age, gender, or income ( Brydges et al., 2025 ).

Today, there is a growing discussion about the diversity of approaches to studying the concept of flourishing and its implications. There are several models of flourishing that have been proposed and are commonly cited in the literature, having both similarities and differences ( VanderWeele, 2017 ). Novak et al. (2024) discuss the increased interest in flourishing in recent years and analyze the instruments that measure flourishing, concluding that despite obvious structural similarities, flourishing instruments have significant differences at the component and item level, which suggest future consensus among researchers on what flourishing really entails ( Novak et al., 2024 ). The same position regarding the different forms and aspects of well-being research is supported by other researchers. The main question concerns the concept of overall well-being and the well-being sustainability across a number of balanced and harmonized systems e.g. personality dimensions, self and others, people and environment, and time ( Lomas et al., 2024 ).

In this study flourishing is considered within the PERMA model, which includes positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishments ( Seligman, 2011 ). For each of these flourishing domains there is a large body of research on their relevance to well-being. Positive emotions are reported to support well-being and furthermore, can be cultivated over time ( Fredrickson, 2001 ). Positive emotions lead to better physical and mental health ( Fredrickson and Levenson, 1998 ; Danner et al., 2001 ) and stimulate physical, intellectual, social, and psychological resources ( Fredrickson et al., 2003 ). Engagement is related to flow theory ( Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 ) and is associated with higher levels of happiness, fewer depressive states ( Seligman et al., 2005 ), and greater life satisfaction ( Peterson et al., 2005 ). Positive relationships with others are strongly associated with well-being ( Seligman, 2012 ) and better personal performance ( Gable et al., 2004 ; Diener and Biswas-Diener, 2008 ; Fowler and Christakis, 2008 ; Tay et al., 2012 ). Meaning in life is confirmed as an antecedent of better health and higher satisfaction with life ( Steger, 2012 ). Achievements facilitate psychological well-being ( Brunstein, 1993 ), especially the achievement of internal goals, as well as perceived accomplishments ( Seligman, 2012 ). Personality predictors – personality traits and personal dispositions – are related to flourishing.

Personality traits from the Big Five model have been reported to be significant predictors of wellbeing (McCrae and Costa, 1991; DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; Mann et al., 2021). For personal dispositions, there is evidence that coping is related to well-being (Otero-López et al., 2021), especially active (Lee et al., 2019), assimilative and accommodative coping (Brennan-Ing et al., 2013; Arends et al., 2016), and coping potential (Smith and Kirby, 2009). In this study, we also consider ineffective coping in terms of adaptive and ineffective behavioral models, specifically learned helplessness, self-handicapping, rumination, and planning. Learned helplessness represents passive behaviour and an inability to learn when faced with stressful, uncontrollable, and unavoidable adverse events, triggered by the automatic defensive transfer of negative past experiences (Seligman and Maier, 1967; Elliott and Dweck, 1988; Dweck and Yeager, 2019). Self-handicapping is related to motivation theory (Atkinson, 1964; Greenberg, 1985) and is viewed as an anticipatory defense aimed at protecting oneself and self-esteem in the face of possible adverse developments (Jones and Berglas, 1978). Despite the different approaches to mindfulness, it has also been shown to be a predictor of well-being (Brown and Ryan, 2003; Baer et al., 2004; Carson et al., 2004; Grossman et al., 2004; Carmody and Baer, 2008, Giluk, 2009; Jones et al., 2011; Eberth and Sedlmeier, 2012; Hanley and Garland, 2017). In practical terms the benefits of mindfulness, reported in various therapeutic approaches (Kabat-Zinn, 1994; Segal et al., 2002; Grossman et al., 2004) reveal its relation to self-regulation and adaptive potential. Research confirms the positive relations of mindfulness with well-being and the Big Five (Brown and Ryan, 2003; Giluk, 2009; Stahl and Goldstein, 2010; Bergen-Cico et al., 2013; Rizer et al., 2016; Hanley and Garland, 2017; Ortet et al., 2020). Self-esteem has a specific role in personal adjustment and better performance (Diener and Diener, 1995; DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; Oishi et al., 1999) and is also related to the Big 5 (Robins et al., 2001; Varanarasama et al., 2019) and well-being (Sowislo and Orth, 2013). Studies demonstrate that meaning in life and search for meaning predict happiness (Park et al., 2010; Steger et al., 2014), positive emotions, self-esteem, optimism, life satisfaction (Ryff, 1989; Compton et al., 1996; King et al., 2006; Steger et al., 2009), and well-being (Zika and Chamberlain, 1992; Ryff and Keyes, 1995). Meaning in life is an important part of psychological well-being (Mascaro and Rosen, 2005; King et al., 2006; Steger et al., 2006). Search for meaning is conceptualized differently - as inner process with positive correlation with psychological well-being (Ryff, 1989) and as a deficit need in the case of frustration (Baumeister, 1991; Klinger, 1998).

With respect to learning to flourish, evidence for pathways to promoting well-being and flourishing is highlighted. Conclusions reveal that variety of positive experiences and feelings is another important dimension that enhances subjective well-being, flourishing, resilience, and prevents hedonic adaptation ( Brydges et al., 2025 ). The broaden-and-build theory describes the way, in which positive emotions can broaden individual’s thought-action repertoire ( Fredrickson, 2001 ) and form a self-reinforcing cycle of upward spiral of positivity ( Fredrickson and Branigan, 2005 ). Recently, during the pandemic, a variety of not only interventions but also educational approaches have been implemented to support individual flourishing by the means of training in well-being skills, mobile app-based mindfulness interventions, academic courses in the philosophy of happiness ( Colaianne et al., 2025 ). This is in line with the plenty of research on learning coping strategies and behavioural patterns, targeting well-being and flourishing in long term.

Materials and Methods

Aim and hypotheses of the study

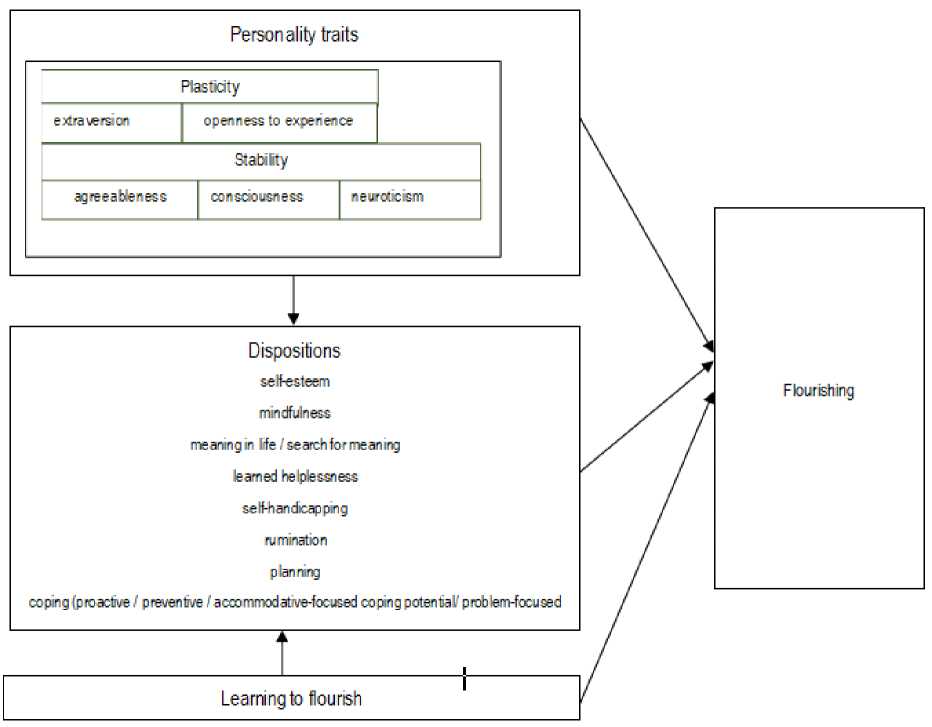

The aim of this study was to examine the direct, mediated, and moderating effects of personality traits and dispositions on flourishing and the opportunities for enhancing personal resources to achieve optimal self-regulation (Fig. 1) and has four hypotheses:

-

H1: Personality traits will predict flourishing with low to moderate effect

-

H2: Personal dispositions will predict flourishing with higher direct effect compared to personality traits

-

H3: Personality traits and personal dispositions will have direct, mediated, and moderated effects on flourishing

-

H4: Training, devoted to enhancement of personal potential for self-regulation will have effect on flourishing predictors and flourishing

Figure 1. Research model

Scales

Ten scales were administered, all with a 5-point Likert response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither disagree nor agree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). All scales had been adapted, with three direct translations and one back-translation and psychometric properties validated for each scale used (component analysis and reliability). The scales include 1) The Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) ( Steger et al., 2006 ) - a 10-item scale that forms two subscales for meaning in life (α = . 885) and search for meaning in life (α = .898), each one comprising 5 items. 2) The Planning scale – a 10-item scale created for the purpose of the study The items were selected with an expert panel from a pool of 30 items, following the long- and short-term planning model ( Lynch et al., 2009 ; Steinberg et al., 2009 ). Two subscales are formed (each of 5 items), measuring planning as important (α = .636) and as unimportant (α = .624). 3) The Mistake Rumination Scale ( Flett et al., 2020 ), a 7-item unidimensional scale (α = .838). 4) The 25-items Self-Handicapping Scale ( Rhodewalt, 1990 ) (α = .775). 5) The Learned Helplessness Scale (LHS) ( Quinless and Nelson, 1988 ) 20-items scale (α = .933). 6) The Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale ( Rosenberg, 1965 ) 10-item scale designed to measure global self-esteem (α = .821). 7) The Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale - Revised (CAMS-R) ( Feldman et al., 2007 ) 10-item scale (α = .863). 8) Coping was measured with two subscales for proactive and preventive coping and two subscales for accommodative and problem-focused coping potential. The proactive and preventive coping subscales are derived from the 55-item Proactive Coping Inventory (PCI): A Multidimensional Research Instrument ( Greenglass et al., 1999 ). The proactive copying subscale contains 14 items (α = .893), and the preventive copying subscale contains 10 items (α = .846). Coping potential was measured as accommodative-focused coping potential (α = .903) and problem-focused coping potential (α = .927) scales that include 12 items each one ( McLain, 2012 ). 9) The Big Five Inventory (BFI-2) ( Soto and John, 2017 ) 30-items scale, having 6 items for each of the five personality traits Extraversion ( α = .733) ; Agreeableness ( α = .613) ;

Conscientiousness ( α = .731) ; Neuroticism with 1 item removed ( α = .780) ; Openness to Experience with 1 item removed ( α = .687). 10) The 8-items Flourishing Scale ( Diener et al., 2009 ) (α = .908).

Procedure and Participants

Table 1 . Distribution of respondents

Total

|

Gender women men 300 (66%) 155 (34%) |

455 |

||

|

Age below 25 years 25-35 years 105 (23%) 152 (33%) |

above 35 years 198 (44%) |

455 |

|

|

Family status – Alone With partner living 65 (14%) 97 (21%) |

With family 243 (54%) |

Prefer not to answer 455 50 (11%) |

|

|

Occupation only study only work 94 (21%) 55 (12%) |

work and study 256 (56%) |

neither work nor study 455 50 (11%) |

|

|

Subjective sufficient to cover insufficient to cover assessment of their needs their needs incomes 218 (48%) 150 (33%) |

unwilling to answer 87 (19%) |

455 |

|

To test H4, a control group and an experimental group were formed. The training was carried out in the period April 2022 - December 2022. The training consisted of 10 sessions over a period of 3 months. The results were compared within the experimental group and between the experimental and control groups at three points in time, before and after the training and 6 months after the completion of the training. The expectation was that the training would improve measured performance. The design included measures of personal dispositions before and after training as proximal outcomes and the flourishing indicator as a distal outcome. To test this hypothesis, we assessed outcomes before training (T1), after training (T2), and six months after training (T3). Participants were recruited by invitation to undergraduate humanities students. After students agreed to participate, they were directed to a pre-test survey. All surveys were administered electronically using the survs.com platform. Scales from the main survey were used, with the exception of the Big Five inventory. Personality traits were not included as a scale because no change in them was expected as a distal outcome.

The idea of the training was to examine whether learning alone, delivered to students without reported need or search for support, will be beneficial. In order to form the experimental and control groups, the recruitment was done in two steps to ensure equality and an initial good level of performance. All 73 undergraduate students of a bachelor programme were invited to participate in a training session and 20 of them expressed interest. All 73 students were administered the pre-training scales. The equality of the control and experimental groups prior to the training was ensured by selecting respondents who were willing to participate in the training and those who were not, with levels of perceived flourishing, meaning in life, mindfulness, proactive coping above the theoretical mean of the scales, and defensive behaviours below the theoretical mean of the scales, without significant differences between the control and experimental groups. This led to a reduction in the number of participants for the training to 13. After dropouts in T2 and T3, each group had 10 participants in T3 (Table 2).

Table 2. Description of the participants in the control and experimental group

|

T1 March 2022 (N) |

T2 June 2022 (N) |

T3 December 2022 (N) |

|

|

Control group |

20 |

11 |

10 |

|

Experimental group |

13 |

11 |

10 |

The training design included expressive techniques and discussions focused on self-reflection. The ten sessions were delivered over a 3-month period and each session lasted two hours. The topics of the sessions were: creating a safe and secure environment; strengthening sense of self and identity; accepting uncertainty; building assertiveness and strengthening self-esteem; making sense of relationships - self and others; psychological intimacy; motivation and goals; stress management; self-expression; well-being. The training framework was based on stability and plasticity meta-traits, suggested in the cybernetic theory ( DeYoung, 2006, 2105 ), extrapolated as two lines of personal functioning, having research and practical potential towards describing and promoting effective behaviours. The design of the training was based on Seligman’s Flourishing Model ( Seligman, 2011 ) and Appraisal Theory ( Smith and Kirby, 2009, 2011 ). Evidence for effective and lasting change toward improved personality traits ( Steger et al., 2021 ), the role of phototherapy in increasing meaning in life, life satisfaction, and positive affect, and decreasing negative affect ( Steger et al., 2014 ) were also considered in the design. The overall goal was to promote a proactive mindset - because for the proactive person, coping is not a singular response, but a consistent pattern of behavior ( Schwarzer, 1999 ).

Data Analysis

Data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and Process v.3. The steps of the analysis were principal component analysis with rotation and reliability test using Cronbach’s alpha and item analysis, descriptive statistics, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, analysis of variance, correlation analysis followed by direct linear effects of personal dispositions, regression models for the effect of Big Five on flourishing and personal dispositions and of personal dispositions of flourishing and general regression models including all personality traits and personal dispositions. Afterwards the mediating role of personal dispositions was examined, and the moderating effect of personality traits was sought for personal dispositions with an independent effect. Mediators and moderators were selected based on reported relationships and predictor models for personality traits and personal dispositions for flourishing and personality traits for personal dispositions. Comparisons between the control and experimental groups were made using t-tests. All outliers were removed. All variables were within the acceptable range of kurtosis and skewness - from -2 to +2. When necessary, a correction for normalization was made, using the logarithmic transformation, despite the prevalence of non-normal data, especially in social sciences (Blanca et al., 2013). Standard rules were followed for component and reliability analysis (Boateng et al., 2018; Moretti et al., 2019). For all scales Cattell’s scree plot and an exploration analysis by principal components method with Varimax rotation was performed with Kaiser-Meier-Olkin test for overall sample adequacy - KMO value > .600; valid result of the Bartlett’s test of sphericity to test correlations between variables (accepted criterion for significance is p < .01); generated factor model explaining 50% of the total variance given extracted factors with eigenvalue > 1.0 (Kaiser normalization criterion) and given the sample size value of the factor weight >.400 (in view to the conservative criterion of including in the pattern-matrix only items with factor weights of .600 and values depending on the sample size). In terms of reliability the value of Cronbach’s alpha was > .700 (with adjustment for brief scales of .600); the correlation between individual items and the whole scale was greater than .400 (using the Spearman-Brown prediction formula). For regression adding additional predictors that explain a significant amount of additional variance for the criterion, with an inclusion criterion of p = .1. All regression analyses had 95% confidence intervals, collinearity and prescreening for outliers was performed. For the mediation analysis, a preliminary screening of the data for assumptions of univariate normality was performed with determination of skewness and kurtosis of distribution below the acceptable threshold for excess (±2) and (±7) for kurtosis (Hair et al., 2010). Screening for outliers was also performed using Cook’s distance and no potential outliers were detected (they were removed at the stage of checking the validity and reliability of the scales). The mediation analysis followed the standard steps - 1) the independent variable to have a significant relationship with the dependent variable; 2) the independent variable to have a relationship with the putative mediators; 3) the mediator to have a significant relationship with the dependent variable; 4) when controlling for the mediator, there must be a significant change in the effect of the independent variable (Baron and Kenny, 1986) for full and partial mediation. The total effect and unstandardized coefficients were reported (Preacher and Kelley, 2011; Edwards, 2013) as if the value 0 does not fall within the confidence interval generated to determine the significance of the mediated effect, it is concluded that the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the relevant mediator is significant. Moderation analysis followed the requirement variations in the level of the independent variable to cause significant variations in the level of the mediator variable (path “a”); variations in the mediator variable to cause significant variations in the dependent variable (path “b”); when path ‘a’ and path ‘b’ are controlled, the total effect of the independent on the dependent variable (path ‘c’) to differ from the measured direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable (path ‘c’) by a residual, which is denoted by the equation c = c’ + ab, where the product ‘ab’ calculates the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

Results

Individual variables and correlations

The individual variables of marital status, age, gender, subjective assessment of income, and occupational status (work/study, study and work, and neither study nor work) had partial individual effects on flourishing and were not reported as independent predictors in the regression models, nor as moderators of the relationships between personality traits and dispositions and well-being. The total variance in flourishing accounted for by the aggregate effect of the individual variables is small (R2 = 0.090). Among the individual effects, higher flourishing is experienced by people who are professionally and developmentally engaged, who rate their income as sufficient to meet their needs, and who are over 35 years of age. There were moderate positive partial correlations between flourishing and the personality traits and meta-traits (r(455) = .389 to .526; p < .001). Personality traits had low and moderate positive correlations with selfesteem, meaning in life, planning, mindfulness, and coping (r(451) = .331 to .583; p < .001) and low to moderate negative correlations with learned helplessness, self-handicapping, rumination, and search for meaning (r(451) = -.169 to -.447; р < .05). Self-esteem had low to moderate positive correlations with meaning in life, planning, mindfulness; coping (r(451) = .263 to .618; p < .001) and negative with search for meaning, learned helplessness, self-handicapping and rumination (r(451) = -.306 to -507; p < .001). Meaning in life had low to moderate positive correlations with planning, mindfulness, coping (r(451) = .269 to .634 ; p < .001) and negative with search for meaning, learned helplessness, self-handicapping and rumination (r(451) = -.333 to -.468; p < .001). Search for meaning was moderately positively related to learned helplessness and self-handicapping (r(451) = .297 to .316) and low negative correlation with accommodative coping (r(451) = -.175; p < .001). Planning had low positive correlations with the four coping variables (r(451) = .139; p < .001) and negative with learned helplessness and self-handicapping (r(451) = -.182; p < .001). Mindfulness had moderate to high positive correlations with the four coping variables, self-esteem and meaning in life (r(451) =.338 to .705; p < .001) and negative with learned helplessness, self-handicapping, and rumination (r(451) = -.194 to -.482; p < .001). Rumination had moderate positive correlations with self-handicapping and learned helplessness (r(451) = .505 to .558; p < .001) and negative with coping variables (r(451) = -.324 to -.505; p < .001). Self-handicapping and learned helplessness had moderate positive correlation (r(451) = .599) and negative correlations with proactive, preventive, accommodative and problem-focused coping (r(451) = -.169 to -.507; p < .001). Coping scales had moderate to high positive correlations (r(451) = .402 to .802; p < .001). Proactive coping had moderate positive correlations with self-esteem, meaning in life, and mindfulness (r(451) = .582 to .622; p < .001) and negative with self-handicapping and learned helplessness (r(451) = -.412 to -.508; p < .001). Preventive coping had low to moderate positive correlations with self-esteem, meaning in life, and mindfulness (r(451) = .263 to .491; p < .001) and negative with self-handicapping and learned helplessness (r(451) = -.139; p < .001). Accommodative coping had moderate positive correlations with self-esteem, meaning in life, and mindfulness (r(451) = .382 to .705; p < .001) and negative with self-handicapping and learned helplessness (r(451) = -.221 to -.653; p < .001). Problem-oriented coping had moderate positive correla- tions with self-esteem, meaning in life, and mindfulness (r(451) = .489 to .668; p < .001) and negative with self-handicapping and learned helplessness (r(451) = -.386 to -.599; p < .001).

Regression analyses, moderation and mediation

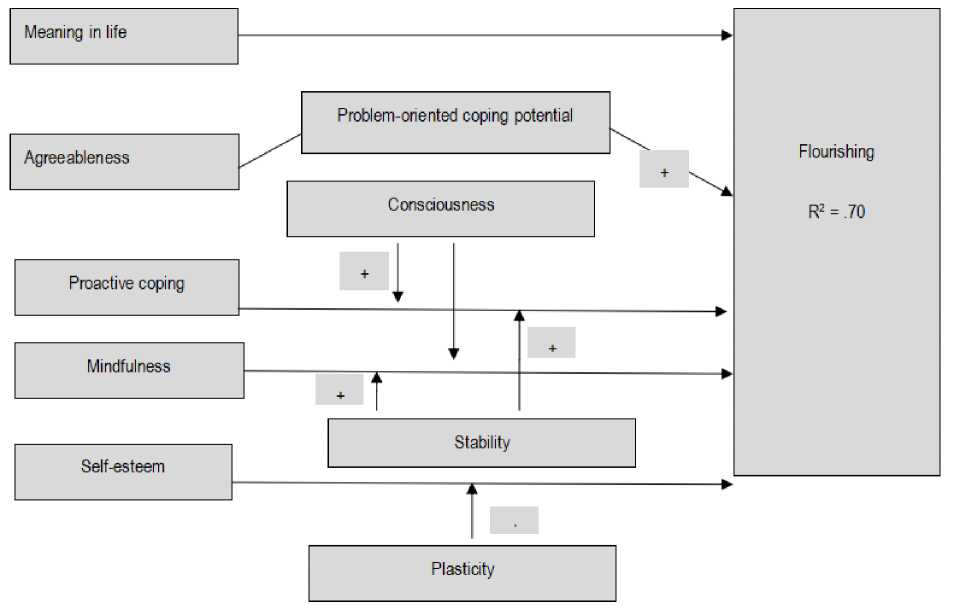

The model of personality traits with the highest explanatory power for flourishing (R2= .373 Durbin-Watson = 1,950; F = 31,488; р = .001) outlined as individual predictors agreeableness (ß = .247), extraversion (ß = .232), consciousness (ß = .190), and neuroticism (ß = -.219). After adding the meta-traits independent effect was accounted for plasticity (ß = .349), agreeableness (ß = .263), and neuroticism (ß = -.241), however the total variance explained by the model was lower (R2 = .310; Durbin-Watson = 1.731; F = 37.45; р = .001). The meta-traits model predicting flourishing (R2 =.352; DW = 1.747; F = 62.42) accounted independent effect of plasticity (ß = .305) and stability (ß = .416). The model of personal dispositions (R2 = .672; Durbin-Watson = 1,856; F = 93,79; р = .001) outlined as predictors having direct effect self-esteem (ß = .299), proactive coping (ß = .265), mindfulness (ß = .233), and meaning in life (ß = .208). The general regression model, including personality traits and dispositions revealed model with the highest explanatory power (68%) with individual predictors self-esteem (ß =.275), proactive coping (ß =.270), mindfulness (ß = .220), agreeableness (ß = .138), and meaning in life (ß = .131) (R2 = 0,682; DW = 1.859; F = 97.75; p = .001). problem-focused coping mediated the effect of agreeableness on flourishing and consciousness, stability and plasticity moderated the positive effect of self-esteem, proactive coping, and mindfulness on flourishing.

Concerning mediating effect of problem-focused coping potential agreeableness had direct and indirect effect on flourishing. The direct effect of agreeableness on problem-oriented coping potential was positive and significant (b = .4131; s.e. = .0691; p = .00. [.2769; .5493] with an explained variance of 14%. The direct effect of problem-oriented coping potential on flourishing was positive and significant (b = .7406; s.e. = .0561; p = .00. [.6301; .8511]. The direct effect of agreeableness on flourishing was positive and significant (b = .2631; s.е. = .0626; p = .00. [.1398; .3864]. With R2 = .1939 and F = 54.12; df = 453 (p = .001), the model was significant. Agreeableness was significantly positively related to flourishing with regression coefficient b = .5691; se = .0774; p = .000 [LLCI = .4166; ULCI = .7215]. The indirect effect of agreeableness on flourishing, mediated by problem-focused coping potential on flourishing was positive and significant (b = .3059; se = .0768 [.1611; .4612]. The direct effect of agreeableness on flourishing remained significant (b = .2631; s.e. = .0626; p = .000. [.1398; .3864], indicating that problem-focused coping potential partially mediated the relation of agreeableness and flourishing. Higher problem-focused copying potential increased the positive effect of agreeableness. The effect of proactive coping, selfesteem and mindfulness on flourishing was moderated by consciousness, stability and plasticity. Plasticity moderated the relation of self-esteem and flourishing, and stability moderated the relation of proactive coping and mindfulness with flourishing. All indirect effects were positive at any value of the predictor. An increase in consciousness increased the positive effect of proactive coping and mindfulness on flourishing. Increase of plasticity increased the relation of self-esteem and flourishing. Proactive coping and mindfulness predicted high flourishing, which increased as stability increased (Table 3).

Table 3. Moderating effects of consciousness, plasticity, and stability

|

coeff se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

constant |

-2.6576 .8724 |

-3,0460 |

.026 |

-4.3765 |

-.9381 |

|

proactive coping |

1.5577 .2293 |

6.7946 |

.000 |

1,1059 |

2,0095 |

|

consciousness |

.0522 .2442 |

4.3096 |

.000 |

.5711 |

1.5333 |

|

proactive coping * consciousness |

- .2280 .0621 |

-3.6715 |

.003 |

-.3504 |

-.1056 |

|

conditional effects of the predictor at values of the moderator consciousness |

|||||

|

3,17 |

.8357 .0624 |

13,0595 |

.0000 |

.7126 |

.9587 |

|

3.83 |

.6836 .0592 |

11,1975 |

.0000 |

.5669 |

.8004 |

|

4.50 |

.5316 .0809 |

6.9425 |

.0000 |

.3721 |

.6911 |

|

R2 = .5610; MSE = .2010; F = 94.99; df1 = 3; df2 |

= 451; р = .000; X*W R2-chng = .0265; F = 13.48; р = .0003 |

||||

|

coeff se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

constant |

-2.6008 .7856 |

-3.3104 |

.0011 |

-1,1489 |

-1,0527 |

|

mindfulness |

1.6483 .2187 |

7.5364 |

.0000 |

1.2173 |

2,0793 |

|

consciousness |

1,1978 .2225 |

5.3838 |

.0000 |

.7594 |

1.6363 |

|

mindfulness * consciousness |

-.2834 .595 |

-4.7607 |

.0000 |

-.4007 |

-.1661 |

|

conditional effects of the predictor at values of the moderator consciousness |

|||||

|

3,17 |

.7509 .0589 |

12.75 |

.0000 |

.6349 |

.8670 |

|

3.83 |

.5620 .0564 |

9.96 |

.0000 |

.4508 |

.6732 |

|

4.50 |

.3731 .0778 |

4.80 |

.0000 |

.2198 |

.5263 |

|

R2 = .7335; MSE = .2116 ; F = 86.55; df1 = 3; df2 |

= 451; р = .000; X*W R2-chng = .0470; F = 22.66; р = .000 |

||||

|

coeff se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

constant |

-2.7748 1,1864 |

-2.34 |

.0202 |

-5,1127 |

-.4369 |

|

self-esteem |

1.6241 .3180 |

5,11 |

.0000 |

.9975 |

2.2508 |

|

plasticity |

1,1631 .3360 |

3.46 |

.0006 |

.5009 |

1.8252 |

|

self-esteem * plasticity |

-.2536 .0879 |

-2.89 |

.0043 |

-.4268 |

-.0804 |

|

conditional effects of the predictor at values of the moderator plasticity |

|||||

|

3,08 |

.8423 .0699 |

12,04 |

.0000 |

.7044 |

.9801 |

|

3.67 |

.6943 .0566 |

12.26 |

.0000 |

.5827 |

.8059 |

|

4,17 |

.5676 .0771 |

7.36 |

.0000 |

.4156 |

.7195 |

|

R2 = .5555; MSE = .2035; F = 92.91; df1 = 3; df2 |

= 451; р = .000; X*W R2-chng = .0166; F = 8.33; р = .0043 |

||||

|

coeff se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

constant |

-4.6060 1.3703 |

-3.36 |

.0009 |

-7.3064 |

-1.9056 |

|

proactive coping |

1.8677 .3542 |

5.27 |

.0000 |

1,1696 |

2.5658 |

|

stability |

1.6600 .3910 |

4.25 |

.0000 |

.8894 |

2.4306 |

|

proactive coping * stability |

-.3285 .0990 |

-3.32 |

.0011 |

-.5236 |

-.1335 |

|

conditional effects of the predictor at values of the moderator stability |

|||||

|

3,17 |

.8272 .0666 |

12.42 |

.0000 |

.6959 |

.9585 |

|

3.61 |

.6810 .0564 |

12.07 |

.0000 |

.5699 |

.7921 |

|

4,06 |

.5353 .0761 |

7.04 |

.0000 |

.3854 |

.6853 |

|

R2 = .5908; MSE = .1874; F = 107; df1 = 3; df2 = |

451; р = .000; X*W R2-chng = .0202; F = 11,02; р = .0011 |

||||

|

coeff se |

t |

p |

LLCI |

ULCI |

|

|

constant |

-3.5725 1.2625 |

-2.8296 |

.0051 |

-6,0605 |

-1,0845 |

|

mindfulness |

1.6817 .3417 |

4.9216 |

.0000 |

1.0083 |

2.3550 |

|

stability |

1.5508 3.3676 |

4.2191 |

.0000 |

.8265 |

2.2752 |

|

mindfulness * stability |

-.3137 .0970 |

-3.2340 |

.0014 |

-.5048 |

-.1225 |

|

conditional effects of the predictor at values of the moderator stability |

|||||

|

3,16 |

.6881 .0621 |

11.08 |

.0000 |

.5657 |

.8105 |

|

3.61 |

.5485 .0559 |

9.82 |

.0000 |

.4384 |

.6586 |

|

4,06 |

.4094 .0781 |

5.25 |

.0000 |

.2556 |

.5632 |

|

R2 = .5415; MSE = .2100; F = 87.78; df1 = 3; df2 |

= 451; р = .000; X*W R2-chng = .0215; F = 1.46; р = .0014 |

||||

In the general model, flourishing was predicted by high self-esteem, proactive coping, mindfulness, agreeableness and meaning in life. Problem-oriented coping potential mediated the relationship between agreeableness and flourishing. Conscientiousness and stability moderated the relationship between proactive coping and mindfulness with flourishing, and plasticity moderated the relationship between selfesteem and flourishing (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. General model of flourishing

Effect and sustainability of the training

In accordance with the design of the piloted training, the results were examined with a comparison between the control and experimental groups before the training, after the training and six months later. The comparison between the control and experimental group after the training is analogous with the results after six months. Significant difference with large effect size (t = 2.4507; p < .05; d = 1.10) for all participants was reported only for meaning in life (control group M = 3.80; SD = .836; experimental group M = 4.60; SD = .595). For individual participants there were changes in mindfulness and coping both after the training and six months after its completion.

Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of this article is twofold: to contribute to two of the main lines of current flourishing conceptualization and in particular to highlight the various predictors that describe levels of perceived flourishing and the practical implications of learning to flourish. Overall, our hypotheses are confirmed. Personality traits predict flourishing with low to moderate effect; personal dispositions predict flourishing with higher independent effect compared to personality traits; personality traits and dispositions have direct, mediated, and moderated effects on flourishing. Personality traits account for less variance in flourishing compared to dispositions, and traits and dispositions have both direct and indirect effects on flourishing. Among personality traits flourishing is predicted by high consciousness, agreeableness, extraversion, stability and plasticity and low neuroticism. Predictors of flourishing with independent effect among the studied dispositions are self-esteem, proactive coping, meaning in lifer and mindfulness. These findings replicate the conclusion that personality traits and dispositions are robustly related to well-being (DeNeve and Cooper, 1998; Grant et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2018; Meléndez et al., 2019; Anglim et al., 2020) and that traits and self-esteem predict flourishing (Fernández et al., 2023). To some extent, personality traits and to a greater extent personal dispositions determine the importance of personal adaptive potential and developmental resources, which replicates that behavior is predicted by situational appraisals and coping preferences in addition to accounted for life course and other changes in personality traits that require further research (Bleidorn et al., 2022). In the general model, flourishing is predicted by high self-esteem, proactive coping, mindfulness, agreeableness, and meaning in life. Problem-oriented coping potential strengthens the relationship between agreeableness and flourishing. Conscientiousness and stability enhance the positive effect of proactive coping and mindfulness on flourishing. Plasticity strengthens the relationship between self-esteem and flourishing. This finding supports the proposed balance and joint effect of the two meta-traits, with plasticity and stability being the two dispositions specifically related to selfregulation. Self-esteem is expected to be not only stable and rigid, but also flexible enough to be revised, validated and supplemented in order to fulfill its optimal relationship with self-perception, while proactive coping and mindfulness, as dispositions related to activity in cognitive, emotional and behavioural aspect, are supported by stability. Personal dispositions and traits have their own independent effects and are also interrelated, so that each variable completes the explanatory model. Personal dispositions can support traits and personality traits have effect on dispositions and their interrelated effect contributes to the understanding of personality antecedents of self-regulation.

In terms of intervention and learning benefits, it is shown that increasing mindfulness and reducing neuroticism can improve mental health ( Bleidorn et al., 2022 ). Intervention approaches and future perspectives for their improvement are outlined ( Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2014 ). Effects and changes are also demonstrated for relatively stable personality traits - changes as a result of experienced crisis situations ( Sutin et al., 2020, 2022 ) and after a three-month intervention ( Stieger et al., 2019 ); changes in traits as a result of mindfulness facilitation ( Van den Hurk et al., 2011 ; Stieger et al., 2019 ) and the influence of values ( Roccas et al., 2002 ). In general, it is emphasized that personality traits are not “fixed,” but rather plastic and change following specific experiences or interventions, as well as depending on the goals set for trait change ( Anglim et al., 2020 ). Colaianne et al. (2025) highlight the role of learning even in a virtual environment, in supporting students‘ mental health and well-being. They report sustainable results with improvements in proximal outcomes related to mindfulness, compassion, and shared humanity and decreases in depressive symptoms and improvements in distal outcomes related to flourishing and depressive symptoms in the end of the course ( Colaianne et al., 2025 ). In this study, there was partial confirmation of the expected promotion of flourishing as a result of the completed training. Participants in the training had significant changes only in the area of meaning in life, but these changes were sustainable and supportive of the learning pathways. Furthermore, meaning in life is reported to be a strong predictor of overall performance and flourishing, and individuals reported higher mindfulness and coping both after the training and six months after its completion, supporting the need for future research. Enhancing predictors of flourishing - mindfulness, coping, meaning in life, and proactive attitudes and behaviors - should act as a learned pathway to flourishing as a proximal and distal outcome.

Studies related to the COVID-19 pandemic highlight effective adaptation patterns and the role of coping potential ( Kirby et al., 2021 ), with significant effects reported depending on the different dimensions and experiences of the crisis ( Sutin et al., 2020, 2022 ). Since the COVID-19 pandemic, it is pointed that universities commit to supporting student mental health and well-being ( Colaianne et al., 2025 ). For this reason, we consider the partial effect of training - sustainable results only accounted for the meaning of life important in view of the conclusion that meaning of life predicts well-being and reduces stressor-related distress ( Ostafin and Proulx, 2020 ) and that supporting individuals’ meaning-making processes promotes health ( Haugan and Dezutter, 2021 ). The impact of a crisis situation on personal resources and coping with a difficult life situation shows that coping with a crisis situation and well-being depend on perceived challenge and meaning ( Selezneva et al., 2024 ). Given today’s unstable and insecure contexts and global crises - economic, social, threats of war, natural disasters - the need to foster resources for sustainable and effective self-regulation and the ongoing search for adaptive responses is of primary interest. We believe that the findings highlight the intersection of the integrated influence of personality predictors and proactive orientations in promoting personal efficacy, adaptive potential, self-regulation, and the role of proactive addressing, supporting the position that flourishing can be learned and that the earlier this process begins, the higher the personal effectiveness will be ( Seligman, 2011 ).

The contribution of the study is to outline the complex framework of the interacting effects of personality predictors on experienced flourishing, and that flourishing can be facilitated through proactive, targeted learning. Taking into account the inherent limitations of a cross-sectional study with a convenient sample, we believe that the results outline the heuristic potential of using plasticity and stability as a general research framework and practical tool that can accommodate traits, dispositions, and learning pathways. On the basis of the research results presented and the training carried out, it can be concluded that not only interventions but also the learning process can be included in order to stimulate personal adaptive resources in the perspective of positive psychology.

Conflict of interests

The author declare no conflict of interest.