Petroglyphs of Zanskar, India: findings of the 2016 season

Автор: Polosmak N.V., Kundo L.P., Shah M.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145367

IDR: 145145367 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0102.2018.46.2.060-067

Текст обзорной статьи Petroglyphs of Zanskar, India: findings of the 2016 season

During the fieldworks carried out by the Joint Russian-Indian expedition in Zanskar (a historical region in the western Himalayas, between the Zanskar and Great Himalayas ranges, part of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, a district of Kargil) in 2016, new petroglyphs were found*. The new site shows certain distinctive features that make it different from other known rock art sites in this region, and present subjects of great scientific interest.

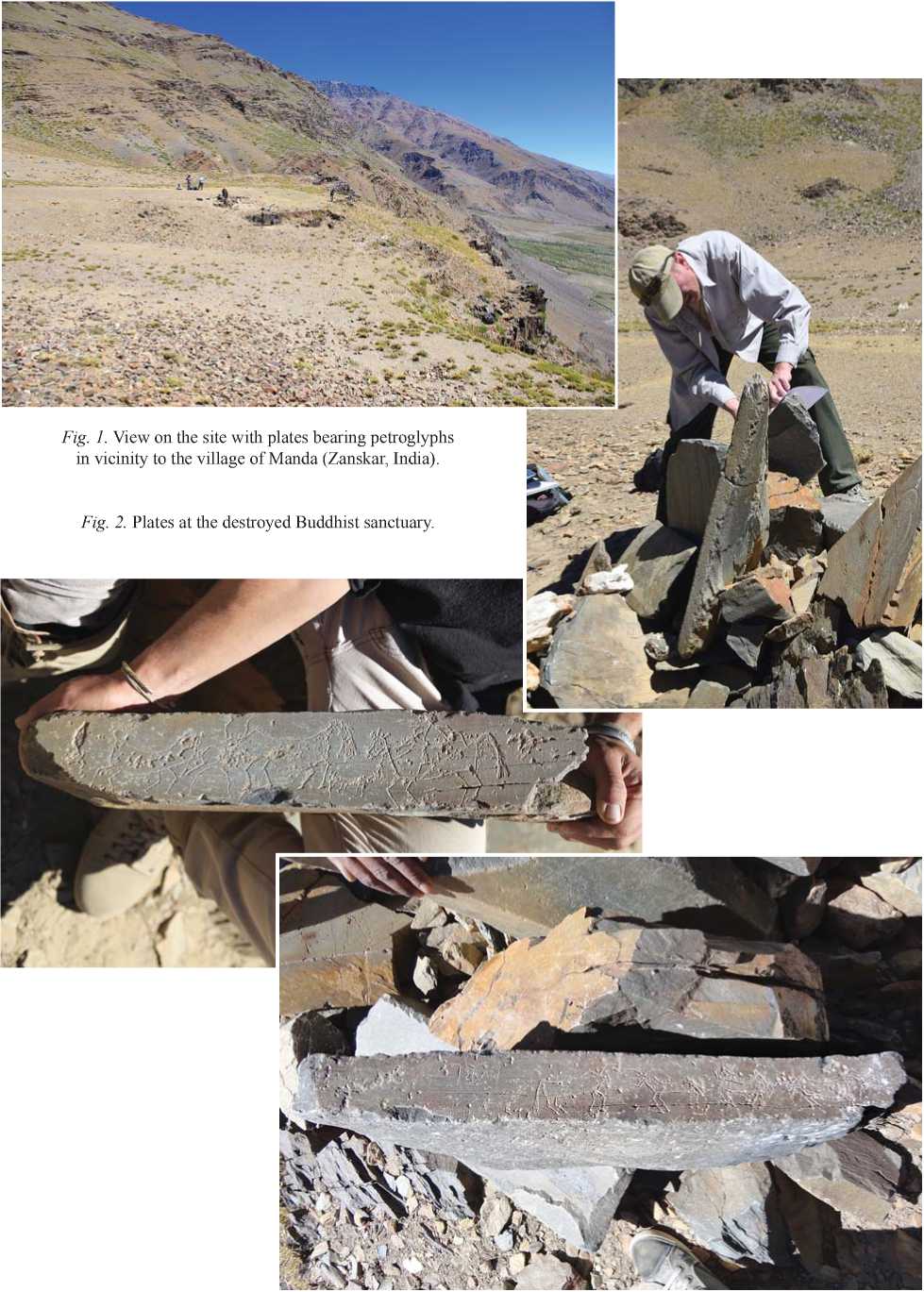

The plates bearing petroglyphs were discovered close to the ruins of an old monastery near the village of Manda, at an elevation of 3878 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1). One of the plates was found at the abandoned sanctuary, consisting of several fractured plates with images of Buddhist deities (Fig. 2); another plate was found among the monastery’s ruins. The plates are narrow stone blocks with rectangular cross-sections and cracked plain surfaces; one of the surfaces of each plate bears images. Petroglyphic monuments of this sort have been discovered in Zanskar for the first time.

The stone plates are rather heavy, yet a single person can move or carry one of them (Fig. 3). This portability makes them different from the stationary cliffs and the huge boulders with petroglyphs. Obviously, the found rock plates with images were used as building materials for later constructions. This tradition has nothing to do with the present-day custom of engraving mantra inscriptions, stupa images, and other Buddhist symbols and texts on small flat stone plates. These stones are usually used in the construction of low many-meter-long walls.

Subjects and images

Narrow plates bear images of yaks. These animals were and still are the most important in the subsistence strategy of the Tibetan population. However, yak images are rather few among the Zanskar petroglyphs as compared to the rock art of Upper Tibet. Far more numerous and popular art images in this region are those of ibex and deer (Bruneau, 2014: 83; Vernier, 2016: 70–71).

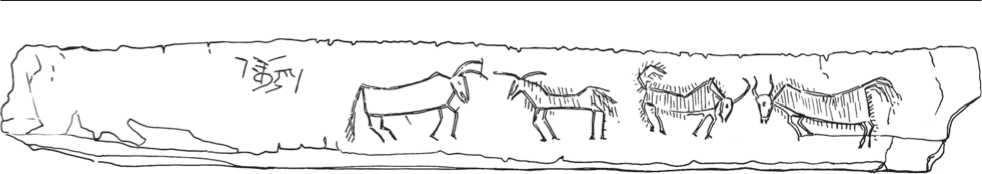

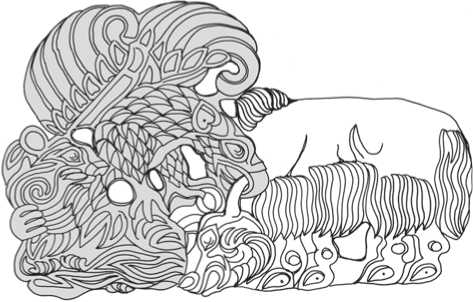

Stone 1 , 62 cm long, with the image-bearing surface 7.3 cm wide, shows a representation of two pairs of fighting yaks. The working technique was pecking with a stone implement, and subsequent rubbing of the silhouette. The realistic animal images are accurately reproduced with few straight lines. The composition stretches horizontally; its borders are delimited by the shape and size of the rock surface (Fig. 4).

The right pair of animals (Fig. 5). Both images show locks of hair apparently executed by some metal instrument along the contours and inside the animal’s bodies. The characteristic humps on the yaks’ withers are depicted by acute angles. The triangular muzzles are typical of the images of these animals in Tibetan petroglyphs. The mouths are half-open. For each animal, only one eye is depicted. The thin lyre-shaped horns are shown in frontal view. The extremities are rendered with thin lines, although in reality the wild yak’s legs are thick, this feature being clearly shown on other known petroglyphs. The yaks with their heads bent down and nearly touching one another with their horns are shown in fight, which is not mortal, but possibly involves serious wounds. One of the yaks turns its bushy tail on its back. The animal on the right looks larger than its opponent; it turns the bushy tassel of its tail down.

The left pair of animals (Fig. 5, 6). The other pair of images is executed in the same artistic manner.

The image to the left is outlined without showing the hair. Both the muzzle with one eye and the sharp horns pointed towards the rival are shown in side view. The ears are indicated. The long tail with a tassel is turned down. The opposing yak, with a tiny triangular-shaped muzzle, is smaller. Short lines along the contours and shadowing the body represent the hair. This yak has a bushy tail and large horns; the ears are notable. The legs of both animals are slightly bent at the knees, as if in motion. Hooves are shown in all four yak images.

The clear part at the left margin of this surface shows traces of pecking, possibly testing marks of the working tool. Next to this, a distinct swastika image is observed, among other lines engraved at random (Fig. 7). The yak images are covered with seemingly irregular pecking marks (see Fig. 6). However, these traces of pointed striking, executed with a stone tool, could suggest the use of these images in some cult practices.

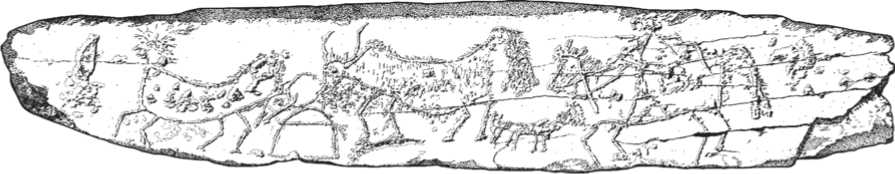

Stone 2 is 49 cm long, the surface with images is 8 cm wide. The composition represents a pair of fighting yaks and a horseman accompanied by a lean dog with pointed ears (Fig. 8). The horseman is trying to lasso the yak next to him. The other animal is shown with its subtriangular head bent down and its horns pointed towards its opponent. The muzzle is rendered with one eye and two thin lines, possibly representing ropes (harness?), which possibly were intended to show that it was a domesticated animal. The bushy tail is turned up over the back. The thin legs are shown in motion. The yak is depicted in an attacking pose. On its body, deep pecked-out holes are observed. A clumsy curl is pecked on the triangular withers; straight vertical lines are pecked all over the body. The right yak is a large animal with a rounded paunchy belly. Its muzzle is rendered in side view by a triangle (with only one eye), while lyre-shaped horns are in frontal view. The ears and a sort of a small head plume between them are well seen. Hair-locks are shown by thin engraved lines along the contours of the body and extremities; the engraved lines cover the body too. The tail is slightly turned up, while the bushy tassel hangs down. The thin legs are slightly bent, as if in motion. Close to the animal’s muzzle and at its belly, traces of irregular pecking are observed (Fig. 9).

Between yak figures, at the back of the composition, a stupa is depicted. Stupa is a Buddhist burial and memorial feature of symbolic and religious significance (Fig. 10). This image was made by the same working technique as that of the yaks: pecking with a stone implement, and subsequent rubbing.

Fig. 1. View on the site with plates bearing petroglyphs in vicinity to the village of Manda (Zanskar, India).

Fig. 2. Plates at the destroyed Buddhist sanctuary.

Fig. 3. Plate with petroglyphs.

Fig. 5. Drawing of yaks’ images on plate 1.

Fig. 6. Representation of the left pair of yaks.

Fig. 7. The left side of the plate bearing traces of irregular pecking and swastika.

Fig. 8. Plate 2 with petroglyphs.

Fig. 9. Drawing of images on plate 2.

Fig. 10. A fragment of a representation of fighting yaks with a stupa at the background.

The stupa has the shape of a hemisphere crossed by a horizontal line. Apparently, the artist wanted to show that the stupa consisted of a hemispherical dome over a cylinder-shaped base. Such images of simple stupas of hemispherical shape are quite rare. They are the earliest; their shapes and origins are similar to those of burial mounds. According to a legend, when Buddha was asked what shape he would prefer for his burial structure, he put his coat as a platform and topped it with his charity cup, with its bottom up (Tyulyaev, 1988: 96). The stupas shaped like a hemispherical dome over a round cylinder-shaped platform are dated to the 1st century BC. The latest period of existence of such stupas is not known. The shape of stupas rapidly changed into more complicated forms.

Bruneau developed a classification of the Ladakh stupas, and defined the images engraved on stones as the rare type 2, which has almost no parallels in architecture. However, he suggested certain parallels among the sacrificial stupas at pradakshina patha, surrounding Dharmarajika stupa in Taxila. Bruneau made a reference to the discovery by J. Marshall, a leader of the excavations at Taxila, that some of the stupas consisted only of a dome resting on a barrelshaped base constructed on the ground. Such stupas are dated to the 1st century BC (Bruneau, 2007: 65). Thus, the stupa image indicates the old age of the discovered petroglyphs.

On the same stone, the image of a horseman can be seen on the right. The horse is shown in the same artistic manner as the yak images: with straight lines pecked out on the rock surface and subsequent rubbing of the silhouette. The sketchy image renders many interesting details that have never been noted before*. The horse’s head is shown in frontal view; both eyes and ears are visible. There is a decorative element over the horse’s forehead: either a sheathed forelock or a head plume. A thick and short-cut mane is depicted by thin, densely engraved lines. The long tail is either plaited or sheathed, and bifurcated into two bushy locks at the end. A breast tassel serves as a decorative element. The horse is shown in movement, with its thin legs slightly bent at the knees, in the same way as the yaks’ legs.

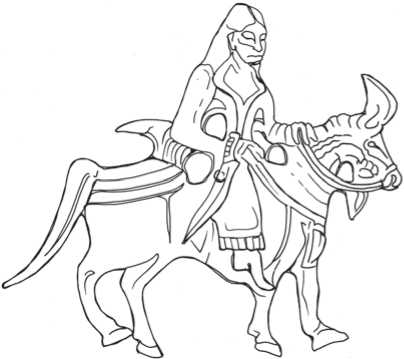

Such elements of the warhorse’s decoration set as sheathed forelock, plume, and breast tassel, appeared comparatively early. These are well known from the early horse images from the Assyrian, Achaemenid, and later the Sasanian bas-reliefs. Such horse trapping decorations were widespread in Central Asia and China, where equestrian culture was developed under the influence of nomads. This decoration set marked the horseman’s high rank (Okladnikov, 1976: 178–184). As an example, noteworthy is a Chikoy horseman’s image engraved on a bronze plate (found on the Chikoy River in Buryatia), which is attributed to the Xiongnu culture (Fig. 11). A plate found near the village of Manda shows a depiction of a horse intended for war and hunting rather than serving his herdsman owner. Equestrian images among the Ladakh petroglyphs are few (according to Bruneau, their proportion doesn’t exceed 13 % of all anthropomorphic representations); images of saddle and rein are even rarer, and those of horse harness have not been found at all (Bruneau, 2014: 94).

Fig. 11. Drawing of the image on the bronze plaque found by chance on the Chikoy River in Buryatia.

The horseman’s image is made in a stylized manner: his triangular body is divided by a horizontal line at the chest; the head is missing, and one of his hands holds reins, the other a lasso (?). He is trying to catch a ferocious animal with the lasso, rather than kill it. A dog assists the horseman. It seems that while the yaks are fighting, the horseman is getting ready to attack. According to P.K. Kozlov, “During the yaks’ fight, one can easily approach them… In a state of arousal, they do not even pay any attention to a shot” (1963: 242). The dog’s image is typical of the Tibetan petroglyphs, which usually depict lean dogs with pointed ears (Bruneau, 2014: 83) that have nothing to do with the Tibetan mastiffs guarding herds of cattle in Tibet nowadays. The Manda dog image likely represents a hunting dog.

The petroglyphs on the plates reveal plenty of important information. The stupa image correlates the age of the petroglyphs with the period of introduction of Buddhism into this region. However, the type of the stupa belongs to a considerably earlier period than the time that is usually regarded as the initial introduction of Buddhism in Tibet and the reign of Trisong Detsen (656–797?). (Tucci, 2005: 19). Giuseppe Tucci argued that Buddhism penetrated into Tibet not only from India and the neighboring states of Nepal and Kashmir, but also from the territories of present-day Afghanistan, Gilgit, and from the cities along the caravan routes of Central Asia (the Great Silk Road) and from China (Ibid.: 35). Such an early penetration of Buddhist traditions to Zanskar, a remote and high-altitude region of Tibet, seems incredible. Nevertheless, researchers have never excluded such a possibility. Tucci believed that Buddhism might have been introduced into this region prior to the officially acknowledged period recorded in the written sources (Ibid.). Phenomena and events that might have taken place during preceding periods and were not recorded in chronicles remain largely unknown. Only rare finds, such as the one discussed in this article, shed some light on these events. Ancient artists tried to render their images realistically, although petroglyphs are usually rather conventional. The images of the wild yaks, horse, dog, and man are strikingly true to life. Apparently, the image of stupa is likewise realistic; it was a typical feature of everyday ancient life, which does not exist in this region any longer.

Tibetan art was greatly influenced by the Central Asian cultures. Noteworthy are the quite few but very impressive images of yaks in the nomadic culture of Central Asia. Images of this animal were popular among these people, who watched yaks and used them in their everyday life, which was in the late 1st century BC to early centuries AD. The images of yaks discovered by archaeologists so far belong mostly to the Xiongnu culture; though these were likely created for nomads, rather than by them. Such images executed in the so-called animal style represent the yak as an ungulate tormented by a carnivore (a griffin or a tiger). An example of a yak image can be seen on the golden plaque from the Siberian Collection of Peter the Great that is attributed to the Xiongnu culture (Fig. 12). Similar images occur on felt carpets from the elite Xiongnu burials (Fig. 13). A golden plaque bearing a realistic image of a yak was found in the burial of the Han period in Wusu, Tacheng Prefecture in Xinjiang, situated in the northern part of the ancient Silk Road (Fig. 14) (Qi Xiashan, Wang Bo, 2008: 235). The wild yaks have no foes, apart from humans. A yak is invincible. As such, the wild yak is rendered

Fig. 12. Drawing of the image on the golden plaque from the Siberian Collection of Peter the Great.

Fig. 13. A fragment of the felt carpet with appliqué yak image from burial mound 20 at Noin-Ula (Mongolia).

Fig. 14. Drawing of the yak image on the golden plaque from the Han burial at Wusu (Xinjiang, Tacheng Prefecture) (Qi Xiashan, Wang Bo, 2008: 235).

Fig. 15. Plate with Bon swastika-image, found in the ruins of the Buddhist sanctuary at Manda in Zanskar.

Conclusions

The petroglyphs found in Zanskar open a new page in the history of the rock art of this region. The images were executed on narrow stone plates, which were portable. These images are very likely not unique, and represent a hitherto unknown tradition. We are sure that a targeted search for such petroglyphs in Zanskar would lead to new discoveries.

The meaning of the rock art compositions on the plates is twofold. The first meaning is evident: the fight between male yaks during rut, and the horseman trying to lasso one of the animals. The second in Tibetan petroglyphs as a divine creature (domestic yaks were not portrayed in rock art). Representations of yaks being tortured, typical of the Xiongnu culture, are dramatically different. In Tibetan rock art, yaks are often portrayed as a hunted game, but this a heroic hunting that does honor to the hunter, because the yak is a fierce and unpredictable animal.

The analysis of these images on plates makes it possible to attribute the petroglyphs to the 1st century BC, which was the time when equestrian culture emerged in Tibet. The image of a simple (archaic) stupa is also dated to the 1st century BC. Apparently, the proposed parallels indicate the earliest possible date, but this doesn’t exclude the possibility that the images with archaic stupa and a horse in ceremonial attire of Central Asian style could have also been drawn later.

meaning is sacral; it is not as obvious, but is implied. In the Tibetan culture, the yak is one of the most important animals. It was the basis of the well-being of the population; this animal was equally important in religion and everyday life*. Suffice it to say that according to an ethnogenetic legend, one of the Tibetan tribes (the Nglok people) were descendants of wild yaks (Ogneva, 1992: 506). The yak played an important role in the ancient Bon religion, which predated Buddhism: one of the cosmogonic myths held that a yak descended from Heaven onto the Earth, and when it butted mountains with its horns, the ground was covered with flowers. Thus, the act of creation was completed, and the yak accomplished a most important deed by making the earth suitable for human habitation and theophany (Tucci, 2005: 275). The images of fighting yaks on the plates found in the monastery ruins are probably connected with these archaic, but not yet vanished, ideas. A narrow plate, nearly square in crosssection and showing the Bon swastika (Fig. 15), found at this sanctuary in association with broken plates with bodhisattva images, can serve as confirmation of this assumption.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation (Project No. AZ 16/BE/15). The authors express their gratitude to L.V. Zotkina for her consultations on drawing technique.