Polychrome style in Mangystau, Kazakhstan

Автор: Astafyev A.E., Bogdanov E.S.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.48, 2020 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145495

IDR: 145145495 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2020.48.2.080-088

Текст обзорной статьи Polychrome style in Mangystau, Kazakhstan

During recent decades, the term “polychrome style” has been broadly used in archaeological papers with respect to both chronology and cultural-historical context. On the one hand, it is easy to use this term as “scientific slang”. On the other hand, it is absolutely wrong to attribute every piece of decoration with inlayed colored stones or glass to the polychrome style, because we deal with a certain cultural phenomenon typical of the period of Barbarian Invasions. It is important for us that the “process of forming and developing the polychrome style is far from being unambiguous”, because it originated from various “ethnocultural roots” and in “different manufacturing centers” (Zasetskaya, 1994: 69). For the artifacts of this style from the western distribution area, there are classification charts with possible places of origin established (Yakobson, 1964: 12–15; Ambroz, 1989: 6–54; Zasetskaya, 1994: 68–112; Zasetskaya et al., 2007: 83–101; Bazhan, Shchukin, 1990; Shchukin, 2005: 340–358; Furasyev, 2007: 23–24), while the information relevant to the Aral-Caspian and Central Asian regions is comparatively scarce (Alkin, 2007: 94–99; Kazakov, 2017). In this respect, the discoveries made by us recently on the Mangystau Peninsula are dramatically important. The Aral-Caspian area is an interlinkage between the

Fig. 1. View on the Karakabak canyon and the Caspian coast. 1 – Karakabak; 2 – cemetery No. 10.

“south” (Sasanian Iran and Central Asia), “west” (Eastern Europe, Caucasus, northern Black Sea region), “north” (Volga region and Urals) and “east” (Tian Shan, Western Siberia, and Altai Mountains).

The first polychrome artifacts were found in the “hoards” in the ritual stone structures at Altynkazgan (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2015: Fig. 4, 12 ; 2018: Fig. 4, 5). In 2019, several cemeteries from the Hun period (Fig. 1) were found in the vicinity to the settlement of Karakabak, which belongs to the period of Barbarian Invasions (for more details, see (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2019)). This article presents the archaeological materials discovered during excavations at burial 2.

Description of the works and the burial rite

The Karakabak Canyon stretches from south to north, with its mouth reaching the shallow Kochak Bay at the Caspian coast. The eastern side of the canyon is formed by a large residual hill; the Karakabak settlement is located on its top. The canyon’s western wall is cut by numerous scours, which form deluvial aprons (slope washes), containing groups (from 3 to 20) of stone structures-piles near the stone circles (Fig. 2).

Before the excavations, Object No. 2 was a stone fill, circular in plan view, 5 m in diameter, with a looters’ (?) pit in the center, which destroyed the stone pavement (up to 50 cm thick) constructed of slabs and rock at the level of the ancient horizon. Along the eastern wall of the pit, to the south, at the same level, a low-ashy spot of burnt soil was uncovered. Along the same line, at the opposite side, 0.3 m from the pit, there was a molded jar-shaped vessel with a handle, dug into the soil up to its neck (Fig. 3, a). The stone pavement covered the entrance to

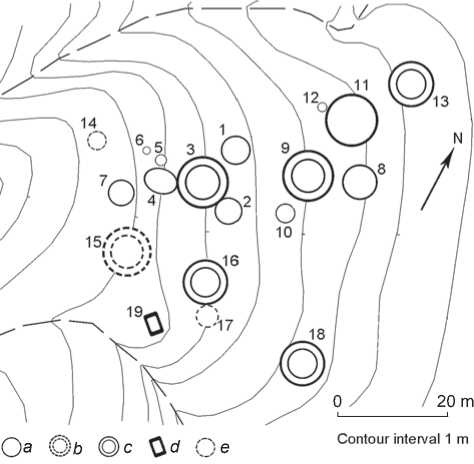

Fig. 2. Location of features at cemetery No. 10.

a – mound; b – mound (?) with a depression in the center; c – stone circle; d – burial of ethnographic time; e – stone fill.

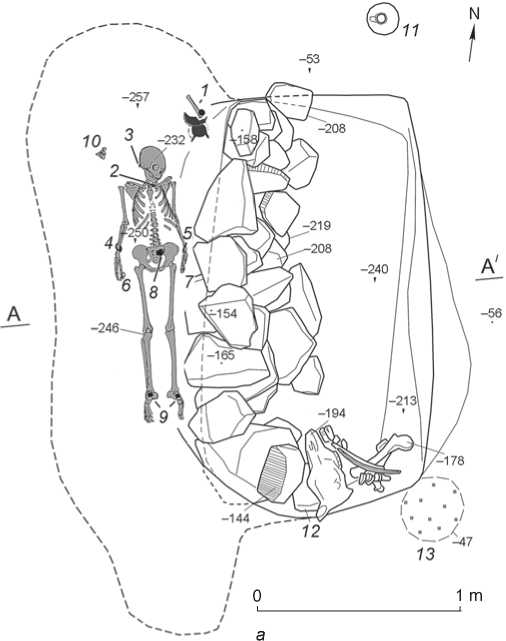

Fig. 3. Plan ( a ), undercut pavement ( b ), and profile ( c ) of burial 2.

1 – a set of grave goods on a wooden dish-tray (a bronze mirror with a stem-handle, a fragment of a bronze mirror showing circular ornament, copper tweezers, a disc-shaped ceramic weight (spindle whorl?), a perforated ammonite piece, a “needle-case” made of the tibia of a caprine animal); 2 – silver pendant; 3 – temple rings; 4 , 5 – copper bangles; 6 , 7 – finger-rings; 8 – silver belt buckle; 9 – silver shoe buckles; 10 – sheep sacrum; 11 – dug-in vessel; 12 – accumulation of ox-bones (skins?); 13 – a patch of burnt soil.

1 m

b

the grave-pit, rectangular in plan view (2.15 × 1.00 m) and oriented along the N-S line. At a depth of 1.0–1.2 m from the ancient surface level, along the western wall, the upper stones of the four-tier pavement, covering the undercut burial chamber, were discovered. The pavement is carelessly made of medium-sized limestone blocks, placed on the step’s edges (Fig. 3, b ). In the southeastern corner of the entrance grave-pit, an accumulation of oxbones (skull with atlas, four hoofs, femur bone, and two ribs) was found.

At the bottom of the burial chamber (the vault is 0.9 m high), in the northern sector of the grave, a skeleton of a woman 20–30 years of age was found, in an extended supine position, with her head towards the north-north-west (Fig. 3, a). The skull shows fronto-occipital deformation. To the right of it, sacral vertebrae of a caprine animal were found in anatomical order. To the left of the skull, at the line of the step, near the burial wall, a set of grave goods was located: copper tweezers (Fig. 4, 2), a disc-shaped ceramic weight (spindle whorl?) 38 mm in diameter, made from a wall fragment of the wheel-thrown gray-clay ceramic vessel (Fig. 4, 5), a bronze mirror with a stem-handle (Fig. 4, 6), a fragment of a bronze mirror showing circular ornament (Fig. 4, 7), a perforated ammonite piece (Fig. 5, 8), and a “needlecase” made from the tibia of a caprine animal (the upper end of the tibia being cut off). Judging by the surviving decay, all these items were situated on a wooden tray or a plate ornamented with the oblique grid motif, with a square of 30 × 30 mm.

Near the mastoid processes of the female skull, there were two paired crescent solid-cast golden earrings (Fig. 5, 2 ). Under the mandible, a necklace (Fig. 5, 1 , 3–5 , 9 , 10 ) was found, consisting of a silver pendant an the inlay of almandine, a heavily patinated rounded glass bead, three global-shaped beads (coral?), and three silver spiral-shaped long beads. Open bronze bangles with slightly broadened ends were found on the forearm bones (see Fig. 4, 1 ). One of them showed a fragment of coarse fabric (clothing?) (see Fig. 4, 1a ). A golden finger-ring with a flat rhomboid signet (see Fig. 5, 6 ) was located in the right clenched fist; a ring of similar type, but smaller in size, was placed on the middle finger on the left hand, with its signet towards the palm (see Fig. 5, 7 ). On the

3 cm

3 cm

1a

3 cm 3

0 3 cm 4

3 cm

0 3 cm

221–245)). These burials were made under individual mounds, mostly in undercuts or in narrow rectangular (oval-shaped) pits. The researchers mentioned above note that the pits with undercuts (mostly in western wall) occur in 70–75 % of the total number of cases. Most often, the undercut is of the same shape as the entrance pit, but slightly larger (2.00 × 0.75 m on average). The deceased were usually placed in an extended supine position, with their heads towards the towards the north. These facts suggest that the population composition in the discussed territories did not change considerably; the processes of migration and assimilation did not alter the worldview, but only corrected dissemination of foreign (Hun) features in clothing and rituals. The custom of circular cranial deformation cannot be considered a chrono-indicator of the Hun Period, and was not directly connected with the Huns. The majority of scholars believe that this custom was initially borrowed from the Sarmatian and Alanian tribes (Iranian-

Fig. 4. Finds from burial 2.

1 – bronze bangles with a textile fragment; ( 1а ); 2 – copper tweezers; 3 – silver belt buckle; 4 – silver shoe buckle; 5 – ceramic spindle whorl; 6 , 7 – bronze mirrors.

sacrum, a silver buckle (Fig. 4, 3 ) was found; on the tarsal bones, two similar but smaller buckles (see Fig. 4, 4 ).

6a

Interpretation of the artifacts

One of the phenomena of the period of the Barbarian Invasions is that all the Late Sarmatian features in the burial rite (for instance, head deformation) were also typical of the Hun Period in the territory of the Ural-Kazakhstan steppes, Volga region, Caucasus and northern Black Sea region (see (Botalov, Gutsalov, 2000: 125–128; Moshkova, 2009: 108–110; Simonenko, 2011: 174–180; Malashev, 2013: 9; Smirnov, 2016: 26–28; Skripkin, 2017:

Fig. 5. Finds from burial 2.

1 – silver pendant; 2 – golden earrings; 3–5 – beads; 6 , 7 – fingerrings; 8 – ammonite; 9 , 10 – fragments of a neck decoration.

speaking steppe dwellers); but exactly during the Hun Period, its distribution range dramatically expanded from the Northern Caucasus to the Middle Danube (for more details, see (Kazanski, 2006)).

The burial rite showed not only features typical of the Late Sarmatian sites, but also some innovations that have not been recorded at the earlier sites in the Aral-Caspian area. For example, it concerns the heap of oxbones (skins?) at the wall of the entrance pit (see Fig. 3, a ). Also known are horse skins buried in the undercut (mostly female) chambers of the Hun Period in the Lower Volga, Crimea, northern Black Sea region, Central Kazakhstan, and Aral Sea region (Zasetskaya, 1994: 17–19; Levina, 1996: 120). Burial of bovine (cow) skins or heads are less typical in the above regions.

The grave goods from burial 2, excluding belt buckles and polychrome items, show broad parallels and “vague” vectors of cultural influences. Noteworthy is a set of goods situated close to the head of the buried woman These artifacts belong to the group of the “Pontic fashion”, and separately they are typical of the cultures of either sedentary or “barbarian” tribes populating Tanais, Crimea, western Ciscaucasia region, as well as more distant peripheral areas. For example, parallels for the copper cosmetic tweezers of a highly trapezoidal shape, with straight or curved ends (see Fig. 4, 2), have been reported from the artifacts of the period of Barbarian Invasions in Hungary (Gencsapáti (Bona, 1991: 103, Abb. 75, 3)); Krasnodar Territory (burial 1, 1948, Pashkovsky cemetery (Smirnov, 2016: Fig. 100)); Crimea and the Lower Don (Mastykova, 2009: 89, fig. 106), and Aral Sea region (Levina, 1996: Fig. 150, 23–25). The mirrors in the Sarmatian style bearing an engraved circular ornament (see Fig. 4, 7) are rather rare; there is only one similar specimen from burial 91 at the Suuk-Su cemetery, in the Crimea (Zasetskaya et al., 2007: Fig. 4, 5). The flat bronze mirrors with thin fillets along the margins and long pin-handles at the sides (see Fig. 4, 6) are comparatively rare in the western part of the ecumene in the Hun period. In the “classic” Shipovo assemblages, only one such artifact was recorded, in kurgan 3 at Shipovo (Zasetskaya, 1994: Pl. 40, 5). However, a similar type of mirror (type II according to A.M. Khazanov’s classification (1963)) with a shorter handle is known from the Scythian period. It was particularly popular among the ordinary nomads of the Sarmatian period in the Volga region and Urals (Smirnov, 1964: Fig. 14, 2a; Khazanov, 1963: 58, fig. 1; Glebov, 2019: Fig. 2), Central Asia, and Kazakhstan (Litvinsky, 1973: 75–76, pl. 1–8). A considerably large collection of such mirrors (but with long handles) came from the Dzhetyasar assemblages (Levina, 1996: 230, fig. 152–155). Other artifacts from burial 2 (spindle whorl, necklace, and “needle-case”), as well as the noted mirror fragments, are generally typical of the Sarmatian and Late Sarmatian periods not only in the northern Caspian region, Volga region, and Southern Urals, but also in the northern Black Sea region.

The solid-cast silver buckles (2 spec., 24 × 13 mm; 1 spec., 32 × 20 mm) with ovoid frames (semicircular in cross-section), rectangular plates with beveled flanges, and cast broad prongs (semicircular in cross-section) with the tips bent down (see Fig. 4, 3 , 4 ), can be dated more precisely, and demonstrate clear vectors of cultural influence. The buckles of this type belong to the Shipovo horizon*, are dated to the 5th to 6th centuries, and have broad parallels among the Bosporan and Central European antiquities (Zasetskaya, 1994: 90–91, pl. 40, 3 ; 42, 6 ; fig. 19, c ).

The polychrome decorations are of the greatest interest among the artifacts from burial 2. Since the recovered finger-rings have very few parallels, we provide a detailed description of them. The first specimen (see Fig. 5, 6 ) shows a rhomboid flat signet (20 × 17 mm) and a similarly-shaped cast 15 × 12 mm in size and 1.5 mm high, with four flat cloisonné inlays of semi-transparent reddish stone (almandine) and one rhomboid inlay of light-brown soft material. Each corner of the signet is decorated with three cylinders 2.5 mm in diameter, to the height of the holder. Three corners preserved inlays of soft light-brown material. At the edges of the signet, bands of corrugated fillets are soldered. The ends of the slightly deformed rail with a triangular cross-section (4 mm wide, the exterior diameter 19 mm) are heavily flattened, brought together, and soldered at the signet. The signet is supported by the corrugated pins, soldered at slight angle to the rail. The second finger-ring (see Fig. 5, 7 ) also has a rhomboid flat signet (16 × 12 mm) and holder (12 × 8 mm, 2 mm high) with a flat semitransparent reddish stone (almandine). The corners of the signet are decorated with cylinders 2.5 mm in diameter, to the height of the holder. One of the corners preserved inlay of soft light-brown material. At the edges of the signet, bands of pseudo-granulation are soldered. The ends of the rail, triangular in cross-section (4 mm wide, the exterior diameter 19 mm), are brought together, and soldered at the signet. Exactly this type of jewelry R.S. Minasyan, the leading Russian expert in the ancient metalworking, considers cloisonné work

*“…‘Post-Hun’, or Shipovo, horizon, bracketing the period between 430/470 and 530/570, the initial phase of which in the general “barbarian” chronology corresponds to the periods D2/ D3 (the Smolin horizon or the Middle Danube phase MD 1: 430/440–470/480), D3 (Karavukovo-Kosino horizon or the Middle Danube phase MD 2, for the ‘Prince’s’ artifacts— Bluchina-Apakhida-Turne horizon: 450–480), D3/E1 (or the Middle Danube phase MD 3: 480–500/510), and the Middle Danube phases MD 4 (510–540/550) and MD 5 (540–560)” (Mastykova, 2009: 19). The dating of the Shipovo assemblages of the 6th to 7th centuries (Ambroz, 1989: 67–75) is not currently acknowledged by researchers.

(Minasyan, Shablavina, 2009: 257, fig. 9). Decoration with the similar thin almandine plates has been noted on the sword-belt buckles and pendants, and elements of the sword and quiver from the Volnikovsky “hoard” (Volnikovsky klad…, 2014: Cat. No. 1–5, 103, 115– 117), which most likely dates to the second half of the 5th century, though the authors of the publication argue in favor of an older date (Ibid., 24–25). The closest parallel to our artifacts is a finger-ring with the signet decorated with cylinders at the corners and containing ruby inlays, from the cache of Bosporus crypt No. 40 (necropolis of Dzhurga-Oba) (Ermolin, 2009: Fig. 5, 3 ).

Following the view of Minasyan and Zasetskaya that upon the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the only centers of jewelry production remained the workshops in Germany and Byzantium, pursuing the Ancient Greek traditions (Zasetskaya et al., 2007: 84), then, the cloisonné artifacts, e.g., decorations from the Volnikovsky “hoard” or from the burials near the farm of Morskoy Chulek, as well as rings and pendants from Dzhurga-Oba, were undoubtedly produced exactly in those workshops and not earlier than the second half of the 5th century. M.B. Shchukin believed that “the cloisonné work could have been revived somewhere in the Western Asian and Eastern Mediterranean countries, in the Rome-Sasanian frontier region” (Iberia) (2005: 346–347). In this respect, the technique of decoration of the Karakabak finger-rings with gem inlays is noteworthy. Originally, the craftsman had laminar blanks of perfect quality with even well-polished edges, but of a size larger than necessary. The blanks were made smaller through rough treatment of the edges made by vertical pressure retouch, and were pressed into the holders. This is clearly seen at magnification (see Fig. 5, 6a). In this case, we undoubtedly deal with imitation: the craftsman was familiar with the original artifacts and the standards of jewelry, but did not have the appropriate tools. Meanwhile, he followed the technology of production for this type of jewelry. For instance, there is a survived thin layer of some light-colored material underlying the gem inlays in the Karakabak finger-rings. At the time of production, this paste-like material was soft and viscous, and later became hard. According to the research carried out by B. Arrhenius, cement and gypsum with various organic admixtures were used mainly (Ibid.: 344). Exactly owing to the chemical analysis of the admixtures, it has become possible to distinguish between the artifacts from the period of Barbarian Invasions and the younger artifacts from the Merovingian Period. Notably, the gems in the younger artifacts were ground twice; this means that the garnets from the artifacts out of use were reused in the new decorations (Ibid.: 345). Application of various pastes made it possible to use very thin plates and save the precious materials, and not to adjust them to the inlay’s width. On the other hand, Arrhenius pointed to another problem: gems fixed with the paste lost their iridescence in the light-rays (Ibid.). In order to avoid this, craftsmen began to place thin golden leaf under the gems, which we noticed in the Karakabak rings. This technique has been recorded in the late Eastern European artifacts, and is associated with the Byzantine school. Their dates (5th–6th centuries) correlate with those of the fifth stylistic group of polychrome artifacts described by I.P. Zasetskaya (1994: 72, fig. 15).

The silver pendant from burial 2 was made in a similar imitative, rough manner (see Fig. 5, 1 ). The edge of the pendant (35 × 21 mm) is formed by a finely corrugated fillet, soldered on an ovoid laminar base. The eyelet is made of three similar fillets soldered together. The holder is low and ovoid (20 × 13 mm); the flattened red stone (carnelian?) projects from it. The inlay is well polished and fixed in the same way as in the finger-rings; the inlay does not show signs of secondary working. In terms of technology, the pendant falls within the chronological limits proposed above for the rings. In this case, the method of forming the holder (ribbed rim) is neither the chronological indicator nor does it reflect the development of technology in the Hun period from complicated (granulation, pseudo-granulation) to simple*.

Unlike the rings, the pendant has so many parallels in Europe, Black Sea region, and Volga region, that to save this paper’s length we will not enumerate all these artifacts here**. This fact proves that such items were very popular among both nomadic and sedentary populations. Apparently, gems of particular shapes and standard sizes were used. This observation made Arrhenius suppose that there was a set of technical standards accepted by the Byzantine craftsmen (see (Shchukin, 2005: 354)). Further treatment of the items (from women’s neck-chest decorations to the onlays on belts and horse harness) might have varied. Currently, a clear picture of the dissemination of the polychrome artifacts of this type from west to east during the Hun and post-Hun periods has been established. During the last twenty years of archaeological studies, the border of the polychrome-style dispersal shifted significantly eastwards in the steppe belt. Formerly, the parallels to the Karakabak pendant would have been limited to the grave goods from the Aral Sea region (Altynasar (Levina, 1996: Fig. 119)); Northern Kazakhstan (near Borovoye Lake (Bernshtam, 1951: 219, fig. 4)); Kyrgyzstan (Kenkol necropolis (Bernshtam, 1940: 24)), and Western Siberia

(Tugozvonovo (Umansky, 1978: Fig. 4), Timiryazevo-1, kurgan 35 (Belikova, Pletneva, 1983: Fig. 45, 1 , 2 ), Krokhalevka-23, kurgan 6 (Troitskaya, Novikov, 1998: Fig. 17, 55 ), Krokhalevka-16, kurgan 1 (Sumin et al., 2013: Fig. 155, 1 , 2 ), and the burial at the Eraska River (Kazakov, 2017: Fig. 1)). Today, the database has been supplemented by the artifacts from burials at the Ilek River (Northern Kazakhstan) (Bisembaev et al., 2018: Fig. 5), in Shamsi Gorge and Boma kurgan (Tian Shan) (Kozhemyako, Kozhomberdiev, 2015: Fig. 14, 16, 17, 19; Ko г omberdieva, Ko г omberdiev, Kozemjako, 1998: Abb. 3, 7 ; 2, 9 , 10 ; Alkin, 2007: Fig. 2, 10 ; Koch, 2008: Abb. 8), and at Arzhan-Buguzun (Altai Mountains) (Kubarev, 2010: Fig. 1). And these are only the eastern parallels to the Karakabak silver pendant; the total of the polychrome artifacts found is considerably larger (see, e.g., (Molodin, Chikisheva, 1990: Fig. 3, 1 ; Borodovsky, 1999: Fig. 1, 1 )). However, S.V. Alkin (2007: 94–95) and A.A. Kazakov (2017: 83) were absolutely right to note that the topic of polychrome style in Central Asia requires further study.

Conclusions

The discovery of the Altynkazgan complex and the Karakabak settlement, containing burials of the Hun period, provides a new insight into the issue of the existence of manufacturing centers in the eastern part of the steppe realm. Presuming that there were no such centers, then all the discovered polychrome artifacts were produced in Europe or Byzantine workshops, and were imported to the Ural-Kazakhstan steppes, Central Asia, and Western Siberia through trade links or with human migrations. M.M. Kazanski (1995: 192–193) believes that these processes were originally stimulated by the politics of the Roman Empire aimed at employment of Sarmatian nomads in its military conflict with Iran. However, we suggest that the process was far more complicated.

First, we should take into account the well-developed jewelry industry in China in the Han period, producing decorations with gold granulation and inlays for the “barbarian” tribes (Alkin, 2007: 95). The fact that Chinese craftsmen were aware of the Western jewelry style, and could produce perfect replicas, is well-known to the researchers of the Scytho-Siberian animal style (for details, see (Bogdanov, 2006: 27–28)). Second, taking into account the mass westward migrations of nomadic tribes upon collapse of Atilla’s Hun Empire, it is highly possible that the captured craftsmen moved together with the aggressors and settled in some distant places. One such place could have been Karakabak, “hidden” in a remoteness, but along the Great Silk

Road. Through this settlement, gems (garnet and others) from India might have been transported to Europe. The possibility of manufacture of the polychrome artifacts in Karakabak is suggested not only by the recorded “barbarian” treatment of gems. The Altynkazgan “hoards” yielded items identical in terms of manufacture: with inlays of almandine and amber and made by cloisonné work (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2018: Fig. 4, 1 , 2 ; 5, 5–8 , 15–18 ), dating to the same period of the 5th to 6th centuries (about parallels and dating, see (Ibid.: 74–75)). Notably, the ritual complex of Altynkazgan is situated at a distance of only 18 km from Karakabak. It is also important that the majority of gold and silver items found at this settlement were produced especially for ritual purposes and were never used in everyday life. The noted identity of items from different “hoards”, as well as the stylistic similarity of the griffin head images on the plates of the horse harness and festive belt from Altynkazgan (Ibid.: Fig. 4, 5), suggest that these artifacts could have been purchased in a single (possibly nearby) craft center, which might have been Karakabak. The most important argument supporting this assumption is the materials recovered during excavations there: 1) hundreds of scraps of copper plates and broken fragments of belt fittings; 2) abundant waste from metallurgical treatment (slags, splashes, and removals) suggesting casting process; this is also supported by the presence of bars and fritted pieces of waste; 3) several dozen small pieces of gems and semi-precious stones (with and without signs of treatment), collected by sieving the soil from the “streets” of the settlement and the rubbish piles. Thus, we can assume that craftsmen of the Byzantine school might have worked in Karakabak and provided the nomadic elite of the Aral-Caspian area with the artifacts in the “Hun fashion”. The links with the Byzantine Empire are indirectly supported by the Byzantine copper coin of Arcadius (395–408), which was found at the Karagan (Mangystau) trade wharf, which was located in the vicinity of Karakabak and was actively used in the Middle Ages (Astafyev, Bogdanov, 2019: 31). It should be noted that at present, only one quarter of the total area of this settlement has been examined. Undoubtedly, subsequent excavations at the cemetery and settlement, as well as anthropological and scientific research (analysis of precious inlays, metal composition, etc.), will provide new data supporting or refuting the assumptions expressed in this article.

Acknowledgement