Prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through archaeological and artistic data

Автор: Oubraham D., Amar R.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 6 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article addresses the topic of the prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through the archaeological remains recorded at various sites, as well as the artistic data found especially in the central Sahara (Tassili and Ajjer), for the meanings they carry regarding the type and form of shelter adopted by prehistoric man. These remains reflect the words: cultures of human groups, their lifestyles, and the different environments across time. They also confirm the organization and management by prehistoric man of the space he occupied, based on the essential resources it provided, such as food, water, and raw materials.

Algerian, prehistoric dwellings, rock shelters, caves; Saharan, rock art

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010754

IDR: 16010754 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.6.15

Текст научной статьи Prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through archaeological and artistic data

RESEARCH ARTICLE Prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through archaeological and artistic data \ > Oubraham Djouher / / / / Doctor (PhD) Institute of Archaeology, University of Algiers 2 Algeria Email Id: ; Orcid: 0009-0008-0696-8086 Amar Rebaine Doctor (PhD) Institute of Archaeology, University of Algiers 2 Algeria Email Id: ; Orcid: 0009-0001-5910-6534 Doi Serial : Keywords Algerian, prehistoric dwellings, rock shelters, caves; Saharan, rock art Abstract This article addresses the topic of the prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through the archaeological remains recorded at various sites, as well as the artistic data found especially in the central Sahara (Tassili and Ajjer), for the meanings they carry regarding the type and form of shelter adopted by prehistoric man. These remains reflect the words: cultures of human groups, their lifestyles, and the different environments across time. They also confirm the organization and management by prehistoric man of the space he occupied, based on the essential resources it provided, such as food, water, and raw materials. / Citation z Oubraham D., Amar R. (2025). Prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through archaeological and artistic data. Science, / Education and Innovations in the Context ofModern Problems, 8(6), 148-155; doi:10.56352/sei/8.6.15. https://imcra- / Licensed © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Science, Education and Innovations in the context of modern problems (SEI) by IMCRA - International Meetings and Journals Research Association (Azerbaijan). This is an open access article under the CC BY license . ; Received: 01.01.2025 Accepted: 17.04.2025 Published: 12.05.2025 (available online)

Since prehistoric times, man has sought to find a shelter or dwelling that would protect him from the cold, heat, and wild animals in the places he passed through. He stayed in the open air, in caves, grottoes, and rock shelters. This is evidenced by the remains he left behind in these places in the form of stone tools, hearths, ashes, and waste remains such as animal bones consumed on the spot. In addition to the drawn and engraved testimonies he left on the rock walls during the Neolithic period, where artists depicted various aspects of their daily lives, including scenes that even showed the form of the dwellings they inhabited.

Through these various remains, researchers have been able to reconstruct and visualize the structure of prehistoric dwellings at many sites around the world, especially in China, East and South Africa, and Europe. One such example is the site of Terra Amata in France (De Lumley H., et al., 2011).

As for Algeria, although there is evidence confirming the existence of dwelling remains dating back to the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, data on such remains remain scarce in these areas compared to the vast number of archaeological sites scattered across the north and the desert regions of the south. Despite the discovery of hearth remains, waste, and arranged spaces in many archaeological sites across different periods, this scarcity may be due to the lack of studies in this 148 – , | Issue 6, Vol. 8, 2025

field, or perhaps to the perishability of the materials used by prehistoric man in building shelters such as hides, wood, branches, and earth which may have deteriorated, erasing traces of the posts or arranged spaces due to various natural factors.

Through this article, we will attempt to identify the remains of prehistoric dwellings in Algeria through various archaeological data that reflect the diversity of dwelling forms adopted by prehistoric man, and which in turn reflect cultures, lifestyles, and evidence of the organization and management of spaces occupied by group members. These patterns were influenced by many factors, particularly essential resources such as food, water, raw materials, and the need for protection, which determined their choice of one location over another for settlement.

-

1. Traces of Dwellings in Algeria Based on Archaeological Data:

The oldest traces of dwellings in North Africa in general, and Algeria in particular, date back to the Lower Paleolithic period, especially at the site of Ain Hanech in Sétif and the site of N’Gaoues in Batna, where stone remains arranged in rows were discovered. These suggest a flooring process intended to stabilize the soil, which was moistened by the constant flow of water.

Man also settled in open-air areas near the banks of ancient rivers and lakes, as well as in caves, grottoes, and rock shelters. The same types of dwellings were inhabited during the Middle Paleolithic period, where humans utilized open-air sites on the High Plateaus and plains, such as the site of Oued Djebana in Bir El Ater, Tébessa, as well as hilly and coastal areas like the sites of Birar and Sidi Saïd in Tipaza.

He also occupied rock shelters and caves, such as the Retaimia cave in Oued R’Hiou, Relizane, south of the Chelif plain, which yielded ash remains and burnt bones indicating periods of human settlement (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Example of a Cave-Shaped Dwelling – Retaimia Site

As for the Epipalaeolithic period and Upper Paleolithic period, current scientific data indicate that the Ibéromaurusian man settled primarily in caves, particularly in coastal areas such as the caves of Beni Ségoual in Afalou, Bou Rhummel in Béjaïa, and Taza,Tamarhat in Jijel. These caves bear witness to repeated periods of occupation by the Mechtoid populations, who left behind various archaeological remains and buried their dead in the same dwellings they inhabited.

They also lived in open-air and hilly areas, such as the site of Colomnata in Tiaret. Regarding the Capsian groups, they made use of open-air sites, especially in eastern Algeria, such as in Tébessa. These sites revealed evidence of long or semipermanent habitation, as shown by accumulated archaeological deposits including waste remains, ashes, and shells.

Humans also settled in lowland areas, particularly in the northern Sahara, where they designated and arranged several spaces for various daily activities. This is documented at several sites, especially at the site of Bordj Mellala in Ouargla, where workshops for flaking and grinding, as well as spaces for food storage and cooking (evidenced by hearth remains), have been found (Aumassip, G. 1994).

During the Neolithic period , the dwelling underwent significant developments resulting from major changes in these communities, particularly in their lifestyles following the emergence and advancement of agriculture and the spread of herding. These changes led humans to build primitive villages, walls, and fortifications for protection, as confirmed by the remains of fortresses in the regions of Dhar Tichitt and Walata in Mauritania (Dupuy Ch., 2011).

However, this did not prevent Neolithic man from continuing to use natural caves such as the Qaldman Cave in Béjaïa (Kharbouche F., 2015) and troglodyte dwellings that spread across the western Oranian regions, as well as caves and rock shelters in the northeastern regions, particularly the areas of Nememcha, Tébessa, and the Aurès—such as the sites of Capéletti , Dibbaba, Arouia, and the Dammous el- Ahmar (Roubet C., 2006).

Similar traces can be found at many sites in the central Sahara from this period, especially in Tassili n’Ajjer, such as the site of Tin Hanakaten, where various remains were discovered: hearths, ashes, bone and manufactured remains, stone arrangements, traces of posts, and pottery inside a rock shelter surrounded by stones forming an outer wall. These stones may have been arranged for protection or designated as enclosures for different herds, indicating human occupation and settlement of the shelter since the 10th millennium B.C (Aumassip, G. 1994, 2003 p.88).

The same applies to the Hoggar region during this period, where humans left numerous traces in the places they used as dwellings, especially at the sites of Aboulag, Adrar Touiyouine in Tefedest, Louny (Maitre J. P., 1971), the site of Meniet in Immidir (Hugot J.H., 1963), and the site of Amekni in Tamanrasset. The latter is considered a model of residential sites in the desert, where traces of a dwelling were found in close granite hollows, likely surrounded by screens or walls made of plant fibers or animal hides for protection, and dated between the 7th and 3rd millennia BC (Camps, G. 1969, 1974).

Researcher Henri Lhote also previously mentioned, through his expeditions in the Tassili region in southern Algeria, the presence of cattle enclosures near the rock shelters, especially at the site of Tissoukai, defined by walls approximately 1 meter high that served to protect the dwelling or shelter (Lhote H., 1966).

As for the Protohistoric period , which coincided with the development and spread of metallurgy in these regions, there is no doubt that the dwelling underwent significant developments with the emergence of fortified villages built of stone. These have been found in many areas of Algeria, particularly in the Saharan Atlas and eastern regions, where remains of walls and stone-and-earth structures are located on mountain slopes and highlands for protection and surveillance. Some researchers attribute these to the Berber period and refer to them using the term “Berber villages,” about which much remains unknown, especially regarding their builders and the exact period of their construction (Camps G., 1974).

However, current data on dwelling remains from this period remain limited, despite clear evidence that humans built dwellings in parallel with the development of funerary architecture and the spread of various types of monuments observed during the Protohistoric era. This scarcity may be due to a lack of research in this field or perhaps because the human groups that lived during these times particularly in the Saharan Atlas and central Sahara were nomadic and relied on tents or enclosures during their stays, leaving no enduring traces of their dwellings.

-

2- The Dwelling Through Artistic Data:

Among the prominent cultural features in rock art particularly in the form of drawings is the representation of enclosures or tents since the pastoral phase, depicted in scenes of settlement or encampment in various and diverse shapes from one region to another, especially oval, circular, semi-circular, and square forms.

In some scenes in Tassili n’Ajjer, even the stages and methods of constructing the tent were illustrated whether elliptical, rectangular, angled, or bean-shaped particularly at the sites of Sefar and Iheren , where women of the Iheren type were depicted assembling the enclosure (Muzzolini A., 1981). These behaviors and activities persisted among Tuareg communities in the central Sahara into the 20th century, where women are responsible for building and organizing the dwelling.

The artist also depicted numerous details of objects and daily furnishings on shelves inside the dwelling, as well as openings, bedding, and other everyday items in many sites, especially at Sefar (Lhote H., 1966).

Figure 2: Women Assembling a Tent – Drawings from Tassili n’Ajjer and Present-Day Touareg (Vernet R., 2013).

The representation of nearly the same shapes of enclosures continued during the Horse Period, especially the circular and rectangular ones, such as those depicted at Tamagert in Tassili n’Ajjer (Aumassip, G. and Tauveron, M., 2003). However, new features began to appear that were previously unknown, such as bags with covers, likely made from leather or plant fibers, resembling those used by present-day Tuaregs. These may have replaced the heavy containers, particularly pottery, which were difficult to transport and prone to breakage due to constant movement, especially with the spread of drought conditions, as seen in the Issalmen shelter in Tassili N.’Ajjer.

The same applies to the Camel Period, during which the representation of rectangular and square tents continued some adorned with zigzag line decorations either on the inside or outside. This is particularly observed at sites like In Touhami, In Itennan, In Bender, and Iheren , where tents were depicted with various lines and ropes tied to them, featuring an opening on one side. These tents resemble those known in the 20th century, with schematic figures drawn inside.

-

3- Description of the Dwelling:

In addition to caves and grottoes that humans used as shelter, the exact form of the dwelling prepared or built by prehistoric man especially during the Neolithic and Protohistoric periods remains largely unknown, particularly in desert regions. This is despite the confirmation by some researchers of multiple material remains indicating the arrangement of dwellings, such as the delineation of circular spaces with various stones, notably found at Bordj Mellala (Texier, J., 1976), Tin Hanakaten in Tassili, and Ti-n Torha in the Acacus (Aumassip, G., 1994), as well as circular arches that some interpret as remnants of dwellings or funerary structures. However, the actual shape of the dwelling and its main components remain unclear due to the absence of walls or ruins that could illustrate its structure.

Through rock art, particularly the painted scenes depicting temporary or semi-permanent encampments of certain human groups, the artist was able to give us an image of the enclosure or tent in which prehistoric man lived. Nevertheless, these artistic data remain relative and should be approached with caution, since the artist does not always provide accurate information about his environment. Subjectivity may influence the depiction, or there may have been social rules imposed by the group or tribe to which the artist belonged.

On the other hand, the valuable information provided by this art form cannot be denied in studying several aspects of the life of prehistoric man.

If we examine more closely the sequential phases of Saharan rock art and the various themes it contains related to dwellings, we find that—as previously mentioned—these dwellings experienced some development in structure and form starting from the pastoral phase and continuing into later periods, where slight changes in form are also noticeable.

According to artistic data , particularly the drawings from Tassili n’Ajjer, the dwelling took on various forms rendered in different colors especially shades of red and white. These were created using either fine or thick line techniques, sometimes as relatively wide bands. The dwellings were composed of a single space or room, represented in diverse forms. In reality, these structures may have been constructed from stone and earth, with added plant branches such as the straw , resembling the current enclosures known among the Tuareg of the central Sahara. Alternatively, they may have been made of leather supported by wooden poles, with an entrance shown as a bundle of branches or leather portable structures used during periods of nomadism, as confirmed by many painted scenes, especially in Sefar and Iheren .

It appears from these scenes that the task of assembling the tent was carried out by women (Iheren ), not men (Figure 2) (Hachid, M. 1998, 2000, 2014). Within these dwellings, there are clearly arranged and designated areas showing containers and everyday objects, likely made from wood, pottery, or gourds, used to store food and liquids on shelves either at the back of the space or to one of its sides.

There were also designated areas for sleeping, where beds were placed, and for sitting. Inside the tent, human figures are depicted in various postures lying down or seated particularly women with their children (as seen in Sefar and the Taouenhik shelter), or both sexes together a man and a woman (as in In In aouarnhat ), or nearby in camping scenes.

From these various scenes, we have attempted to identify certain types of enclosures represented in the rock art, based on their depicted morphological shapes, as follows:

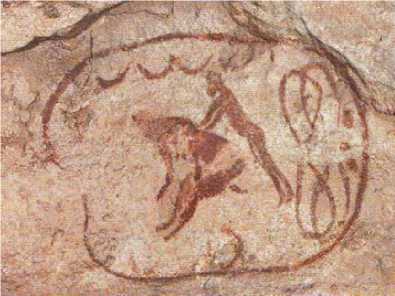

Oval-Shaped Enclosure:

This type is particularly found during the early pastoral Period, associated with figures having black faces (Smith A., 1993). It is represented either by a fine white line (as in Sefar and Tissoukai), or by two lines in red and white (as in In aouarnhat), or a fine red line (as in Sefar and In Itenan), with depictions of various interior furnishings.

This pattern is characteristic of the Sefar Ozan Ehéré group. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Oval-Shaped Enclosure in Tassili n’Ajjer (Lajoux J.D., 2012)

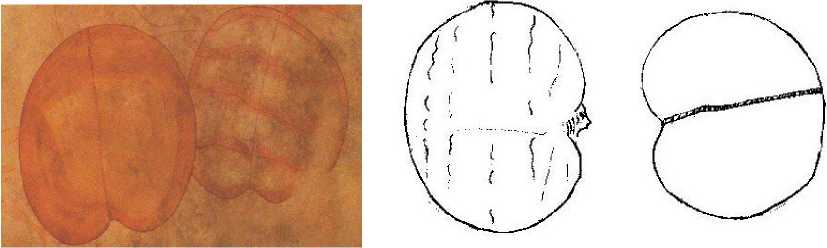

Semi-Circular or Bean-Shaped Enclosure:

This type generally appears in settlement scenes of the Iheren Tahilahi group. It typically takes on a circular shape resembling a bean, with a concave section on one side an artistic detail intended to indicate the entrance (Muzzolini, A., 1981, 1983, 1989 ) (Figure: 4).

Figure 4: Semi-Circular Enclosure – Iheren, Tassili (Hachid M., 2014).

Half-Oval Enclosure:

This form also appeared during the pastoral Period, particularly with the Ozan Ehéré group in Sefar, and contin ued into the beginning of the Horse Period at the Taouenhik site in northwestern Tassili. It was depicted using fine red lines and persisted into the Camel Period as well.

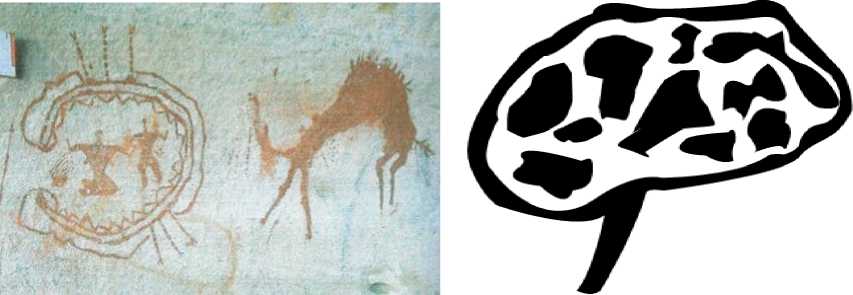

Circular Enclosure:

This type was represented during the pastoral Period, especially in Tassili n’Ajjer, and is associated with figures having white faces (Smith A., 1993). However, its depiction continued into the Caballine and Cameline periods, during which new objects appeared some adorned with fringes, likely made of leather. Inside these enclosures are figures characterized by double opposing triangles and stick-shaped heads (as in Ti n- Abanher) (Muzzolini, A., 1983, 1989) (Figure: 5).

Figure 5: Drawing of a Circular Tent – Tassili n’Ajjer.

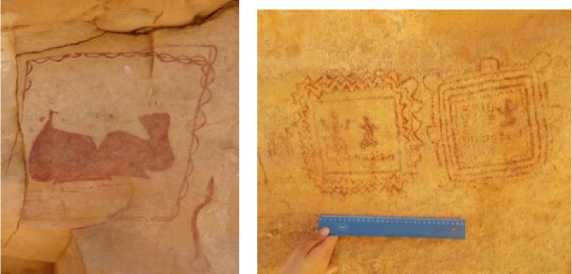

Rectangular-Shaped Enclosure:

This form was widely represented during the pastoral Period, especially at Sefar. It was typically drawn in red, although in some instances it appears in white, either as a thick or fine line, and includes an entrance and interior daily-use items. These enclosures are often depicted alongside black-skinned figures of the Sefar Ozan Ehéré type (Muzzolini, A., 1981) (Figure: 6)

Figure 6: Examples of Rectangular Enclosures – Sefar, Tassili.

Square or Nearly Square Enclosure:

This type is prevalent during the Horse Period at numerous sites in Tassili n’Ajjer, especially at In Bender, Tabarakat, as well as In- Etouhami and Ti-n- Tanifi . It is typically represented in a single color—mainly red—or in a dual color scheme of red and white. These enclosures are often bordered with sets of parallel or dotted lines, possibly for decorative purposes, or may feature geometric shapes or small squares on the exterior.

Inside, they also include figures characterized by opposing triangles and stick-shaped heads, as well as script-like symbols near camels or horses, particularly noted at In- Etouhami (Figure: 7).

Figure 7: Examples of Square or Nearly Square Dwellings – Tassili n’Ajjer.

As for the early phases of Saharan rock art, little is known about the types of tents used by the populations of the Ancient Bubalus Period or the Round Head period, who did not seem interested in representing enclosures in their rock art. These were drawn on the walls of shelters they occupied temporarily. This lack of representation may be due to a general disinterest in the topic or the fact that these groups only occupied such locations for short periods and thus did not prioritize depicting their dwellings, even though archaeological deposits have been found in these shelters. Researcher G. Aumassip confirmed the presence of archaeological remains particularly kaolin used more frequently by the Round Head group (Aumassip, G., 2013).

-

4 – Conclusion:

Studying the topic of prehistoric dwellings in Algeria highlights their significance and diversity across time and space, shaped by varying environments and human cultures. It bears witness to a continuous human presence in these regions and to prehistoric man's ability to adapt to fluctuating environments from the Paleolithic through the Neolithic to historical periods. It also allows us to imagine the criteria for choosing living spaces, based on the availability of essential resources and protection conditions necessary for survival.

Nevertheless, current data on dwelling remains remain limited. More in-depth scientific studies on this subject are still awaited.