Procession of horsemen on a gold plaque from the Siberian collection of Peter I

Автор: Ochir-goryaeva M.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.46, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145401

IDR: 145145401 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2018.46.4.067-073

Текст статьи Procession of horsemen on a gold plaque from the Siberian collection of Peter I

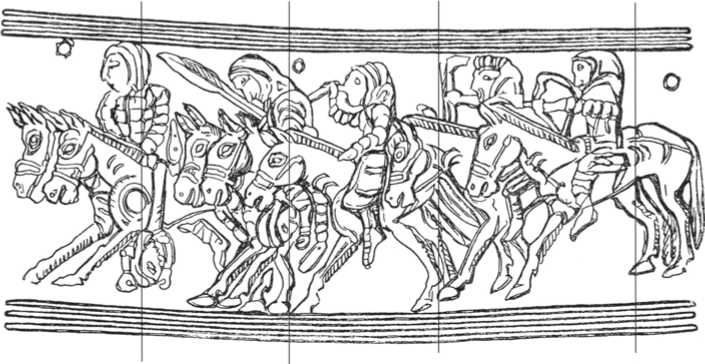

The Siberian Collection of Peter I is chronologically the first archaeological collection in Russia; it contains about 250 artifacts made of gold, some of them recognized as masterpieces of ancient art dating to the period between the 8th century BC and the 2nd century AD. Collected in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, it has been in the focus of scholars’ attention since then. During the research of the role of horses in the funerary ceremonies and culture of nomads of the Scythian period (end of the 6th to 4th centuries BC) in the Eurasian steppe (Ochir-Goryaeva, 2012), my attention was drawn to one of the gold artifacts from the Siberian Collection of Peter I, namely to the gold plaque decorating the rectangular casing featuring a group of horsemen (Fig. 1). A drawing of this item was first published in 1890 (Tolstoy, Kondakov, 1890: Fig. 76). The authors assumed that this was a group of five horsemen, with extra horses accompanying them (attached to one of them was the head of a dead enemy).

M.P. Gryaznov discussed in detail paired belt-buckles from the Siberian Collection of Peter I, one of them depicting a boar hunt and the other featuring a scene of a “rest under a tree”, dating back to the Scytho-Sarmatian period. The researcher offered interpretations of all the artifacts, finding parallels to them in the heroic epics of the Turco-Mongol peoples. As far as the gold plaque in

question is concerned, he strongly doubted that it would be possible to suggest any dates for its chronological identification. While describing the scene depicted on the plaque, he wrote as follows: “There are a number of armed horsemen, forming three rows of two, three, and two persons. One man in the first row and another one in the second row seem to be dead: they were put in saddles or over them, their bodies hanging and heads drooping” (Gryaznov, 1961: 29). Thus, according to Gryaznov, the scene depicts seven horsemen, two of which appear dead.

In a publication devoted to the Siberian Collection of Peter I, S.I. Rudenko identified the representation on the gold plaque as “warriors returning after a battle”.

A drawing of the composition, made by him, differs in minute details from Gryaznov’s sketch. The improvements were likely made to comply with the original (Rudenko, 1962: Fig. 29). As the style in which the horses were depicted (“bridled, saddled, and their mane cropped”) was recognized as “typical of the Gorny Altai ethnic groups of the Scythian epoch”, there were no doubts, according to Rudenko, concerning the artifact’s chronological reference. Besides, he took into consideration parallel details of the horse images from other collection pieces that were dated to the Scytho-Sarmatian time, including the hunting scenes and the one with the horsemen resting under a tree, from the paired belt-buckles mentioned

Fig. 1. The gold plaque from the Siberian Collection of Peter I. The State Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Inv. No. Си.1727-1/132.

0 5 cm

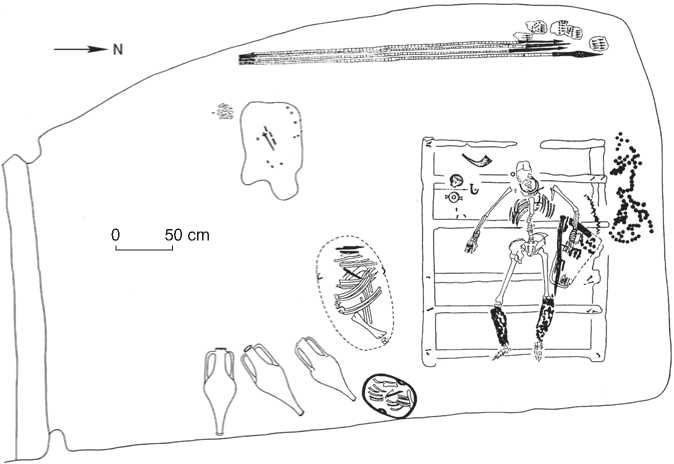

Fig. 2. Drawing of the image (after (Rudenko 1962: Fig. 29)). The facets of the casing are indicated in accordance with a photograph (Ibid.: Pl. XXII, 18).

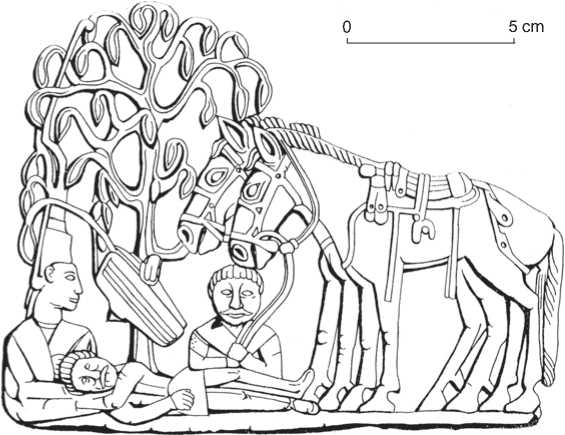

Fig. 3. The image on the belt-casing from the Collection of Peter I (after (Brentjes, 1982: 82)).

above (Fig. 3) (Ibid.: 298). In his other work, Rudenko noted that “the Siberian Collection includes another image, which is not perfect in workmanship, but is of interest in terms of its content. One of the gold plaques… features five horsemen armed with bows and swords, accompanying a corpse put across one of the horses; this may be one of their kinsmen, or an enemy” (1960: 306). Thus, according to Rudenko, the scene on the plaque depicts five horsemen and a corpse. No further effort has been made to offer other if moving at a trot: with legs stretched forward and straight bodies, necks are turned up, and heads are slightly turned down. If the horses had been moving at a gallop, they would have been shown in the appropriate manner, i.e. with corpuses and necks stretching forward, and the heads raised high up.

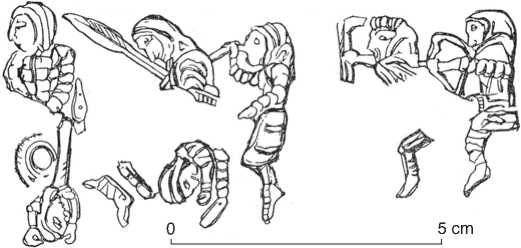

The other drawing depicts only men in the scene, which clearly indicates that there are seven of them (Fig. 4, b). Each man wears a similar sort of armor and a similar piece of headwear that looks like a closed helmet. Unfortunately, the quality of the image does not make it possible to come to stronger conclusions. Now let us determine the number of living and dead horsemen. The two archers, shooting arrows, and two horsemen (one of these (No. 1) leading the procession, and another (No. 2) in the middle row) are alive. Two dead horsemen are put in the saddles, with their bodies hanging limply from the horses’ withers. The body of one of the front warriors hangs over from the right side of the horse, so that the viewer can see his head and right leg. The body of the warrior in the middle row hangs over from the left side of the horse; the viewer can see his head, left arm, and left leg. The horses carrying these warriors follow immediately after horseman 1, in the front row. Gryaznov was the first to point out that these two were dead, while Rudenko noticed only one of them. An even closer look helps to identify another corpse. The horseman in the interpretations of this composition, so that the issues concerning its overall meaning or details, such as the number of the horsemen, both dead and alive, have remained open for discussion.

Analysis and interpretation of the composition

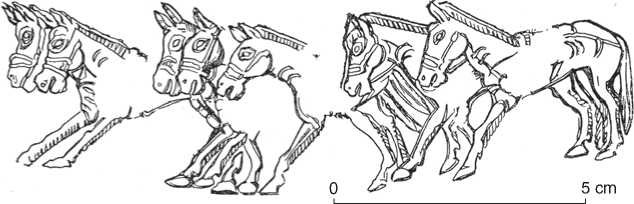

Let us have a closer look at the images of the procession of horsemen depicted on the plaque of the casing. First, let us identify the number of horses; to make the task easier, we shall begin with a drawing, on which the animals’ images are highlighted. The resulting sketch shows seven horses, moving in three rows: two animals leading the cavalcade, three horses in the middle, and other two animals behind (Fig. 4, a ). Each horse is bridled, saddled, and its mane is trimmed. They are shown as

Fig. 4 . Sketches with representations of horses ( a ) and horsemen ( b ).

middle of the group, seating in the saddle, with his head drooping on the wooden spear-shaft, and his back bent limply, is also dead. He is supported by horseman 2, with another stick. This stick and the spear together form a cross-piece, which holds up the dead warrior on the right side. Thus, the image on the gold plaque features seven horsemen, three of whom are dead. Noteworthy is the absence of stirrups in all cases. This strongly suggests that the artifact under discussion should be dated to the Scytho-Sarmatian period. It is well known that stirrups and rigid saddles appeared in the Middle Ages, and nomads of the Early Iron Age used pad saddles, without stirrups. Of key importance in making sense of the processional scene are the images of two archers. The archer in the foreground has his bow bent, but has not yet released an arrow, so that the bow and the string form a sub-rhombic figure, with his left arm passing through the center of the figure, and his fist holding the medial part of the bow tightly. The other archer is in the background; he has released his arrow, the bow making a straight line, its lower part is not visible to the viewer, and its upper part is bent. His left hand is still holding the bow, with the fist tight on its medial part; the string is not shown. It seems strange that the archers are depicted with their bows targeted in a direction similar to that of the moving group, in the manner of escorts. But it should be taken into account that the casing is rectangular; the image of each side is separated from the others with straight lines (Fig. 2). Hence, it appears that while the cavalcade is moving, the archers aim their arrows in a direction perpendicular to the procession’s movement. This fact was of crucial relevance, because it prompted an interpretation of the whole scene on the gold plaque as that of a funeral procession. In accordance with ethnographic evidence, while carrying their male dead to their resting place, Mongolian-speaking Buryats and Western Mongols (Oirats) used to shoot arrows, aiming them in the direction of their homes or towards their enemies, and either picked the released arrows up on the return journey or sent a horseman immediately after them. Afterwards, the arrows were kept by the family of the deceased. This might have had a symbolic meaning of transferring life energy and sustenance to the family. According to the available ethnological data, the Buryats used to transport the deceased to the place of interment on his best horse, saddled and bridled in the best way. The dead wore their full armor and were put in the saddle to be supported from both sides; the horses were led by one of the ritual’s participants. One of the arrows was shot in the direction of the dead man’s house, to be picked up on the return way from the cemetery (Semeynaya obryadnost…, 1980: 91–95). F.A. Fielstrup describes this ritual as follows: “Having put the funerary clothes on the deceased, people harnessed a horse and decorated it with the best equipment. The horse was led by a special slave* (“horse’s attendant”). Khun-serge** puts the corpse on the horse, and also helped to dismount it… <…> …the rest of the slaves walked behind and made three circles round the camp… At some distance from the camp, an arrow was shot in the backward direction, and then the funeral proceeded on its way” (Fielstrup, 2002: 113). The ethnographic data support the suggested interpretation of the scene with horsemen as participants of a funeral procession transporting dead persons to the cemetery. This interpretation is also supported by the very small number of participants in the procession. According to the tradition of the recent past, quite few men attended the ceremony at the cemetery. People usually gathered in the house of the deceased for a funeral repast. Importantly, the funeral scene shows two ways of transporting the dead on horseback. The first way is represented by the two horsemen: the one leading the procession and the one in the middle row. The corpses were seated in the saddles and put on the horse’s withers, hence drooping to one side. Rudenko was mistaken in suggesting that one of the corpses was put across the saddle, though this manner of transporting the dead is known from the ethnographic and folkloric data (Ochir-Goryaeva, 2014). However, seeing that the legs of the first dead man droop on both sides of his horse and the left leg of the next corpse descends parallel to the left arm, there is no doubt that the former keeps this position most likely because he is fastened; in addition, some sort of a ballast on the other side of his horse stabilizes the dead body’s position. This interpretation is supported by details of the image of the deceased in the front row. His body is shown to be drooping to the right, while on the left side of the horse there is an indication of a broad band, winding to the underbelly of the animal, and there is a round object (the size of man’s head) fastened to the band. According to ethnographic data, the dead were put in the saddle to be fixed in this position on one side, while on the other side, a log or a sack full of stones was used for keeping balance (Semeynaya obryadnost…, 1980: 93; Fielstrup, 2002: 112). Thus, it may be concluded that in this image such a method of transportation is depicted.

There is, however, a detail concerning the representation of the dead in the first row, which still requires interpretation. On the pommel of the horse’s saddle is attached an object made up of two vertical boards on its both sides and two rivets on the side surface. The construction resembles a child’s seat (Mong. ermyaalgin), with the boards designed to support the child under the armpits. In this case, it might have been used better to fix the corpse in its position.

The second type of transportation of the dead, depicted on the gold plaque, was more widespread, and had a number of variants, in accordance with ethnographic data. Most frequent are descriptions of the corpse seated in the saddle, with an accompanying person sitting behind it on horse’s croup to support it and not let it fall. In other cases, there were horsemen on each side supporting a corpse in the saddle. The image of the gold plaque demonstrates a somewhat different method of transportation whereby the corpse in the saddle is supported in the vertical position by cross-piece made of a spear shaft and a long stick on one side, and by a horseman on the other side. A similar method is described in the ethnographic literature, but here the cross-piece is fastened to the stirrups. The principle is the same, though details may vary: “Two sticks are put across one another and are fastened to the stirrups, then pass under the chin of the corpse to be tied to the crupper. Two horsemen support the corpse from the sides keeping it with a lasso; one more horseman holds the reins” (Fielstrup, 2002: 112). The cross-piece in the gold plaque scene is shown to be at the level of the dead man’s armpits, and fastened in a different way because of the absence of stirrups.

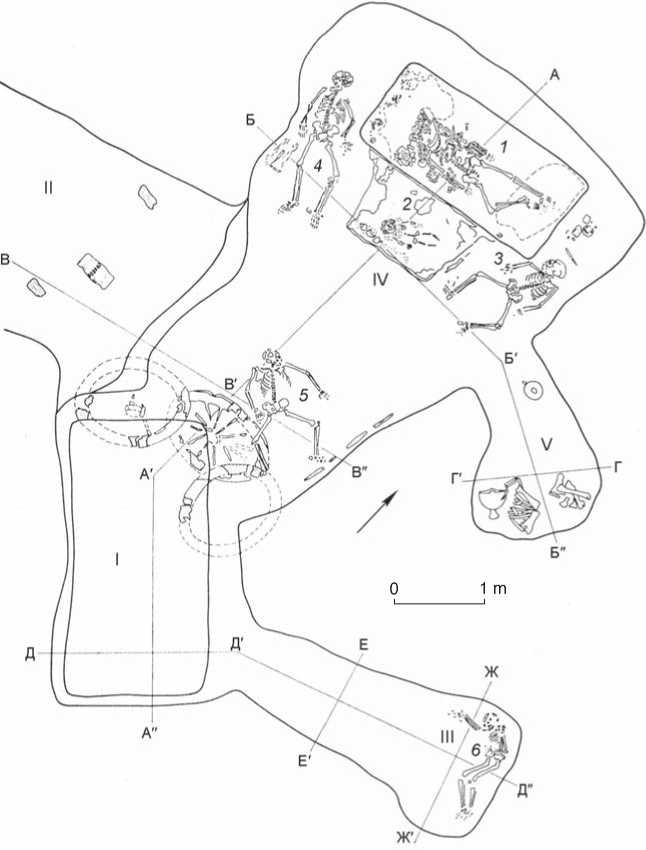

Therefore, it may be concluded that the interpretation of the scene of horsemen on the gold plaque from the Siberian Collection of Peter I as a funeral procession, discussed in detail here, looks quite convincing. Importantly, this small-scale examination supports the suggestion that the artifact in question should be dated to the Scytho-Sarmatian period. In the burials of the Eurasian nomads of that time, the deceased appear to be positioned in their graves in a manner described as a dancing (straddling) posture, or in a “attacker” posture, with one leg flexed and spread, and another shown straight (Smirnov, 1964: 92). The arms of the diseased in such cases were also stretched to the sides. Sometimes, the left arm was flexed and turned as if still holding the bridle, while the right one was slightly bent or stretched, as if holding a whip. Such burials are not abundant but are rather frequently encountered. Here are some examples. In a lateral cist of the Scythian burial mound Tolstaya Mogila, all individuals were buried with widely spread legs: a noble person, a 2 year old child, and also an accompanying servant girl (at the feet), a guard (at the head), and a coachman (near the wheels) (Fig. 5). In burial 2 of the Scythian mound Soboleva Mogila, a noble elderly warrior was also put in a “straddling” position (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5 . Layout of the lateral cist in the Tolstaya Mogila mound (after (Mozolevsky, 1979: Fig. 30)).

I – entrance pit 1; II – dromos from entrance pit 2; III – burial chamber of a servant girl; IV – the main burial chamber; V – household utility niche.

Burials: 1 – tsarina; 2 – child; 3 – “cook”; 4 – “guard” warrior; 5 – “charioteer”; 6 – “servant” girl.

Fig. 6 . Layout of burial 2 at the Soboleva Mogila mound (after (Mozolevsky, Polin, 2005: 161, fig. 91)).

These postures are mentioned by the researchers, but are not interpreted in any way. R. Rolle made an attempt to interpret such a custom. Her idea that the servant girls were subjected to the ritual sexual act before or right after they were killed did not explain the pose of the deceased men with their legs apart (Berg, Rolle, Seemann, 1981: 142–144, Abb. 139–140). There is an opinion that legs were first put on the feet with their knees up, and then, during archaeologization, fell apart (Skripkin, 1984: 74). But in such cases, foot bones are located close and parallel to each other, as in Yamnaya culture burials of the Bronze Age. In our burials, legs are not only flexed but widely spread, i.e. the feet were placed at a distance from each other. For example, O.V. Obelchenko reported such cases in the kurgans of Sogd dating to the 2nd to 1st centuries BC. According to him, the spread legs indicate that the corpses were transported to the graves after being placed in the saddle (Obelchenko, 1992: 118–120). The funeral procession shown on the gold plaque clearly supports this interpretation of the straddling posture of the deceased.

Conclusions

There is another important aspect of the interpretation of the images under discussion. As has been mentioned above, Gryaznov found parallels from the Turco-Mongol epos to each of the artifacts discussed in his paper. The only exception was the image of the funeral procession on the gold plaque from the Siberian Collection of Peter I. Notably, it typical for heroic epics and folklore in general that the protagonists are usually heroic personages ready to perform their gallant deeds, and hence, destined to become immortal and live on in the peoples’ memory. Undoubtedly, the funeral scene does not show an episode from everyday life but, rather, an illustration of a saga or myth. Numerous items of toreutics depicting scenes with people and mythological animals indicate that the Scytho-Sarmatian nomads had a rich mythological tradition, including heroic sagas. In fact, the necessity for special analysis of these issues has been discussed in the archaeological literature as a topic worthy of special attention; but few studies have followed (Grakov, 1950: 7–8; Hancar, 1976; Jacobson, 1993). On the other hand, the works addressing the semantics of images have implied that myths and sagas were known in the Scythian time, and some of their particular elements remain in the folklore and epics of the peoples nowadays as the remnants of the past.

Acknowledgements