"Protecting the mistress": a plaque with an anthropomorphic representation, from Shuryshkary, Yamal-Nenets autonomous district

Автор: Brusnitsyna A.G., Fedorova N.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 1 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145246

IDR: 145145246 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2016.44.1.104-113

Текст статьи "Protecting the mistress": a plaque with an anthropomorphic representation, from Shuryshkary, Yamal-Nenets autonomous district

The early Iron and Medieval Art in northwestern Siberia is mostly represented by the cast bronze images of anthropomorphic creatures, animals, and birds. Bronze portable art-pieces were initially used as objects of cult practices in the Early Iron Age and developed into the art of status-marking objects in the late 1st–early 2nd millennia AD. By that period, a dynamic system of signs was established, consisting mostly of zoomorphic, ornithomorphic, and more rarely anthropomorphic symbols and marking the personal social status. A.P. Zykov (2012: 95) argued that by the 10th–12th century, social stratification was changed as compared to that of the Early Middle Ages. The following social strata appeared: high-ranked citizens and their confidants, all of whom lived in fortified settlements protected by the walls; and the rest of the population, which was subordinate to the highest social rank and lived in unfortified townships.

Within the scope of development of this status-related system, in the 10th–12th centuries, round plaques cast of silver and white bronze emerged in northwestern Siberia. These plaques represent one of the insufficiently studied topics in the traditional cultures of the northern Ob region. Currently, twenty such plaques have been recorded. We are sure that the real quantity of such articles is considerably higher. The plaques bear anthropomorphic images, and also those of fantastic animals and birds. The scenes shown on some plaques shed new light on contacts between the aboriginal population of northwestern Siberia and centers of medieval civilizations. The present publication of the plaque ornamented with the anthropomorphic character, surrounded by the imaginary birds and by “solar” and “lunar” signs from Shuryshkary in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District (hereafter YNAD), appears to be timely and important.

History of the find

The plaque (Fig. 1) was purchased in January 2014 by researchers of the Shuryshkarsky Regional Historical Museum Complex from a Khanty woman residing in this village. For some time, the plaque was the central element of a domestic religious complex dedicated to mother goddess, family patroness securing reproduction.

The previous owners of the plaque perceived the central male image as the image of a woman. They pointed to braided hair and interpreted the arms bent in the elbows and having marked shoulders as a female breast. This misinterpretation attests to the discontinuity in the tradition of the image’s perception. The implication of this scene was clear to medieval people, but it is apparently vague to our contemporaries. Any circumstances of discovery of this plaque are unfortunately missing, yet we can hypothesize its link with the Belaya Gora fortified settlement located in the vicinity of Shuryshkary, which site yielded numerous bronze and silver medieval articles, including a similar plaque with three human images (Fig. 2).

The plaque was regarded as a representation of Kushcha-shavity ne goddess meaning “the woman protecting the mistress”. The plaque was stored in a house, wrapped in cloth together with few small shawls that were specially manufactured and offered to the goddess. Votive goods also included wolverinehide, a saber wrapped in cloth, and a small mammothbone (according to the informant). The set of sacred goods was handed down in the Khanty family, which originated in the village of Uitgort of Shuryshkarsky District, YNAD. It was a matriheritage and was handed down from mother to the youngest daughter. The owner described the purpose of this plaque in simple words: “It helps in having babies”.

When a keeper of this sacred thing acquired age, while her youngest daughter was already married, the mother made a small (ca 25 × 25 cm) offertory shawl okh sham and handed the whole set to the daughter. Taking into consideration that at present the set includes four shawls, it can be assumed that the recent owner was the fifth keeper. Thus, the plaque has been an item of this set for no longer than five generations, i.e. about 150–180 years. Each time a new baby was born in the family, the

3 cm

Fig. 1. Plaque from the village of Shuryshkary, YNAD: obverse ( 1 ) and reverse ( 2 ) sides.

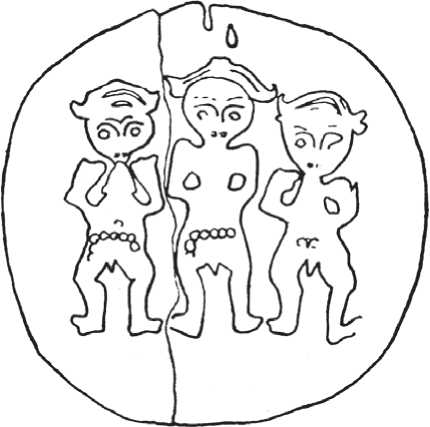

Fig. 2. Plaque bearing three anthropomorphic characters from the archives of the Yamalo-Nenets Regional Museum Complex of I.S. Shemanovsky.

keeper sewed a small “closed” shirt and hung it to the saber. According to the informant, about 25 such shirts were attached to the saber. Every year in mid-summer, the goddess with the whole offertory set was taken to sacred tree decorated with hanging bells, at the family site in Uitgort.

The owner justified the plaque selling by the fact that she did not have daughters and that her granddaughter had a serious disease and needed medical treatment. However, the woman asked us to keep the plaque together with shawls, and she reserved the saber with shirts and wolverine-hide, possibly assuming it more important to keep these things in the family.

Description of the find

The round plaque with the convex front face and the flattened skirting (see Fig. 1) is cast of white bronze. The decoration exhibits slight chisel-working; the surface is polished. The article is 10.0–10.2 cm in diameter; the convexity at the center is 1 cm deep. A hanging-loop was likely soldered at the top; this missing loop left an oval opening. Small casting-defects in the form of metal underand over-filling are noted. The plaque exhibits graphic images or engravings that were made later.

The plaque shows a composition of an anthropomorphic and two ornithomorphic characters, and two images that can be interpreted as solar and lunar signs. The anthropomorphic character is shown in frontal view in the center of the composition. It shows an ovoid face slightly widening in the upper part. The headgear likely represents a helmet with eye- and nose-protecting plates and possibly with a face-mask having an 8-shaped mouth hole. The eye-protection elements are semi-circular, with round “pupils”. The top of the helmet shows a sort of a plume in the form of plaits with decorated ends. The character holds the plaits’ ends with his hands. The arms are bent in the elbows; the hands show four fingers with the thumbs outstretched. Along the line of the shoulders, the arms stand up from the rest of the body. A belt consisting of round plates decorates the waist. The sign of the male sex is depicted below. The legs are shown in side-view, slightly bent at the knees as if in motion. The knees are accentuated with double lines, and the booted feet are separated from the rest of the legs with lines. A round image showing a face in the same headgear as the main character’s is to the right of the latter’s head. Double embossed lines run up, down and on either side of the face, and connect with the embossed circular contour of the image. To the left of the head of the main character, a crescent-shaped image is shown. This semi-circular face in a helmet-like headgear is connected by three double embossed lines with a ridge enclosing the image. Two birds are shown at either side of the main character. A standing bird, apparently a waterfowl, is shown to the left of the central image. The bird has a long neck, an open thick beak, and almond-shaped eyes. Both wings are uplifted and ornamented (as is also the body) with indented triangles. The bird to the right represents a large diurnal bird of prey. Its head is rounded, a large and sharp beak is wide-open, the eye is shown through a small round indentation; the wings are uplifted and ornamented (as are the body and tail) with indented triangles. The legs with feathery pants are large and sharp-clawed.

The plaque is encircled with a double flattened ridge: the inner ridge shows the double-plait motif, and the motif of the marginal ridge varies from double to single plait.

The plaque bears engraved images on the front and back surfaces (Fig. 3, 4). All images, with only one exception, are heavily worn and scratched. The front surface shows an anthropomorphic face image over the head of the main character, under the opening. Two curved lines indicate the eyebrows and nose; two large circles indicate eyes. The mouth is nearly rectangular; three horizontal short lines run from each narrow side of the mouth. Triangular “ears” are shown on each side of the head. Vague outlines of other images are noted between the face and the “solar” sign. These are the feature resembling a trident-shaped headgear, and facial fragments: eyes and sets of short lines (?). The lower portion of the plaque, from the belt-level to the feet of the main character, shows the image of some animal: a fore and a hind leg, and a large head resembling that of a horse or a reindeer. The characteristic features of the animal’s iconography are the location of the eye close to the head-outline, and the transversal line on the neck.

3 cm

3 cm

Fig. 3. Graphic images on the obverse side of the plaque.

Fig. 4. Graphic images on the reverse side of the plaque.

The reverse side exhibits a vague animal image (the head and the upper portion of the body). The image is situated next to the opening.

Analogous artifacts and discussion

Round ornamented plaques cast of silver or white bronze that were subsequently ornamented with engravings appeared in northwestern Siberia long ago. The currently-known 20 plaques include 12 articles kept in various museums; 2 plaques are missing, and the rest are in various private collections.

Four plaques with anthropomorphic images represent the closest analogues to the Shuryshkary article. Two of them were published and are currently deposited in the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural MuseumReserve and the Yamalo-Nenets Regional Museum Complex of I.S. Shemanovsky. These articles are available to researchers (Chernetsov, 1957: 190, pl. XXII; Sokrovishcha Priobya. Zapadnaya Sibir…, 2003: 87). Another plaque is kept in a private collection and is not available for study. One more plaque has been presented as a sketch in the publication by A.A. Spitsyn (1906: Fig. 12); the plaque is apparently missing. All these plaques exhibit a front view of three standing men in helmets, possibly with face-masks. The central character is a little larger than the others. At least three of these plaques also show vague graphic or engraved images.

The silver cast plaque bearing three human images (see Fig. 2) was also discovered in Shuryshkary, and is currently deposited in the Yamalo-Nenets Regional

Museum Complex of I.S. Shemanovsky (Sokrovishcha Priobya. Zapadnaya Sibir…, 2003: 87). The plaque is 11 cm in diameter. The upper part of the plaque is missing; hence it is not clear whether the article was hung or attached in some other way. The plaque shows three male images in the same postures as on the plaque with the anthropomorphic character and birds; the fourfingered hands with outstretched thumb are put on the belly. Other iconographic features on these two plaques are identical: stocky men with large heads are shown in helmets with eye-protection elements or face-masks, an 8-shaped mouth hole, and plaits (?) on the helmet tops; the arms are marked along the shoulders line; the legs are shown in side-view; short lines are seen across the knees and over the feet. Facial images with trident headgear are engraved around the characters.

The plaque bearing images of three warriors, each holding two sabers in their uplifted hands (Fig. 5), was discovered in the 1900s, supposedly in the Shaitansky Cape 25 km from Berezov town upstream the Severnaya Sosva River (Spitsyn, 1906: Fig. 4; Chernetsov, 1957: 189–190, pl. XXII). Currently, the plaque is in the Tobolsk Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve. The plaque is cast of silver (?). Its size is 14.5 × 13.5 cm; it is larger than other known plaques of this sort. The upper part of the plaque shows a big opening with a broken-off edge. The plaque exhibits three warriors in trident helmets with face-masks, typical crescent-shaped eyeprotection elements, and 8-shaped mouths. This plaque shares certain common features with the Shuryshkary plaque: shoulders separated from bodies by sharp semicircular outlines, incised lines under the knees and above

Fig. 5. Plaque found in the vicinity of Berezov town, on the bank of the Severnaya Sosva River.

Fig. 6. Plaque from Siberia (?), published by A.A. Spitsyn (1906).

the feet, and belts of large rectangular plates on the waists. The postures and proportions of characters are also identical: the warriors are shown with slightly flexed legs, the heads are disproportionally large, the stocky bodies and extremities are short, four-fingered hands show splayed fingers and outstretched thumbs. The rightmost character is shown in the same posture as the one on the Shuryshkary plaque. Unlike the two other warriors, he has a type of boot on his feet, with slightly upturned toes. Two embossed circles are exhibited in the upper part of the plaque between human images. The plaque also bears graphic images.

A silver or bronze plaque showing three anthropomorphic characters (Fig. 6) was published by Spitsyn after Medvedev’s sketch kept in the archives of the Archaeological Commission (1906: Fig. 12). This is an incidental find from Siberia, and its location is currently unknown. The article is about 10.5 cm in diameter. There are two openings in the upper part of the article. The margins do not bear any ornamentation; in the center, three anthropomorphic characters are shown; their arms are bent at the elbows and placed on the belly; waists are marked by belts of large plates; legs are bent at the knees and placed apart. The characters wear helmets, details that can hardly be seen on the sketch. However, a certain top-decoration is noticeable on the helmets, seemingly analogous to that on the Shuryshkary plaques. Another important feature that is well presented in the sketch is the mouths, shown in the form of two rectangles.

There is another, fourth cast plaque known to us, with three anthropomorphic images. Regrettably, the plaque is in a private collection and not available for analysis or publication.

Cast bronze anthropomorphic figurines or faces showing iconographic similarity to the image on the Shuryshkary plaque have been typically recorded within various medieval hoards and among incidental finds. They share several artistic features, including the helmet with a face-mask and a mouth-hole in the shape of either a figure 8, two rectangles, or circles (Baulo, 2011: 88, 97–99; Erenburg, 2014: 140; Surgutskiy kraevedcheskiy muzei…, 2011: 79). The characters usually show plaited hair coming down from under (or over) the helmet; shoulders, knees and sometimes feet are separated by incised lines. The images described above, unlike the Shurushkary one, are shown with their feet turned in and hands placed on their bellies.

The image of a large waterfowl with a big beak is commonly represented in hollow pendants manufactured as figurines of animals and birds. These pendants are sometimes designated as beads because they were worn strung on straps. Some researchers define these images as those of a goose. Probably it is indeed a goose; but either possessing imaginary features, or incredibly large. This latter feature made it noticeable in many compositions with other characters. There are several such images known. Most commonly, they show the bird standing, with folded wings and the tail down. An image of a small, likely furry animal is shown on the bird’s chest below the beak (Chernetsov, 1957: Pl. XVIII; Ugorskoye naslediye…, 1994: 93, fig. 117: Baulo, 2011: 197), which is sometimes replaced with a twisted cord motif (Baulo, 2011: 186, 187). In one case, there is an anthropomorphic character in place of this animal (Ibid.: 198). Interestingly, two images were cast in one and the same mould. These are the bird image from the former Tobolsk Governorate (Chernetsov, 1957: 183) and a similar image discovered in the Saigatinsky IV burial site (Ugorskoye naslediye…, 1994: 117). As was mentioned above, all the birds showed folded wings; some images showed two wings at one side. No cast images of birds with uplifted wings have been reported so far. Decoration of wings with triangular motifs, similar to that on the bird images of the Shuryshkary plaque, occurs also on the hollow figurines of waterfowls (Baulo, 2011: 186, 197) and carnivorous birds (Ibid.: 185). Similar decorative motifs have been recorded on the wings of images of carnivorous bird ornamenting the bronze pommels of iron knives (Sokrovishcha Priobya. Zapadnaya Sibir…, 2003: 90; Erenburg, 2014: 146). Most often, the ornamentation-motifs of the bird’s wings and body include lines of “pearls”, fillets, and twisted cords. A carnivorous bird on the Shuryshkary plaque is rather unusual: its head and beak are depicted with a single line, whereas typically such carnivorous birds are shown with their beaks clearly separated from the heads (see, e.g., (Baulo, 2011: 185). The iconographic originality of the Shuryshkary plaque is also reflected in the fact that both birds are shown with open beaks and uplifted wings, i.e. they are represented in motion, unlike the static birds depicted on other bronze plaques.

Available medieval engraved pictures seldom show clear bird-images. They mostly portray some fantastic characters with ornithomorphic features (see, e.g., (Leshchenko, 1976: 180, 181). Birds with one or both wings uplifted have been reported from the engravings made on a saucer from the Yamgort hoard (Ibid.: 187), and on a bronze spoon from the Kheibidya-Pedary sanctuary in Bolshezemelskaya tundra (Murygin, 1992: 37).

The images similar to those depicted on each side of the Shuryshkary anthropomorphic character have been usually interpreted as solar and lunar signs; yet such an attribution is rather debatable. The cast faces inscribed in a circle or semi-circle are rare (Baulo, 2011: 114; Chemyakin, 2008: 32, fig. 2, 4 ). The authors know of six other “solar” and “lunar” cast images that are kept in a private collection. The set of grave-goods from the Barsovsky-1 burial-ground (Barsov Gorodok) yielded a face inscribed in a circle that was formed by two zoomorphic images. The face is linked with the zoomorphic images by vertical and horizontal embossed lines. Anthropomorphic images engraved on a medieval silver plate from a hoard that was discovered in Sludka, Perm Governorate (Fig. 7) (Leshchenko, 1976: 180), represent complete analogues of the images on the Shuryshkary plaque. Similar images were noted on plates from the village of Bolshe-Anikovskaya, and on a saucer discovered in the vicinity of Berezov town. On

Fig. 7. Engravings on the medieval plate from Sludka settlement, Perm Governorate (Leshchenko, 1976: Fig. 20, a ).

the Byzantine plate from Sludka, a round image with a face in the center, connected through double lines with the surrounding edge, is shown to the right of a conventional bird-like image with anthropomorphic features, and a semi-circular image is to the left of it. Thus, the general position of the two figures is the same as on the Shuryshkary plaque. It should be noted that such symbols have not been noted on the engravings dating to the Early Iron Period: the earliest image of this kind is that on the Berezov saucer. Though the saucer has been dated to the 6th century, V.Y. Leshchenko has argued that the engravings could have been made in the 7th–8th centuries or later (Ibid.: 179). Even if this engraving was made in the 9th century, it is the earliest image of this sort known so far.

Images interpretable as the sun and the moon, or as solar and lunar signs, shown in the same position as on the Shuryshkary plaque, often occur on silver round plates bearing hawker images (Leshchenko, 1970: 139– 141). Similar images are depicted on the silver plate with two anthropomorphic characters riding a horse (Baulo, 2011: 246). Such scenes are poorly known in the regions eastwards of the Ob River; the only exceptions are several plaques with hawker images discovered in the Surgut region of the Ob. Most often they occur to the west of the Ob River and in the western Urals.

A similar scene is also known in the ethnic art of the Ugrian and Samoyedic populations of the Ob basin. It is represented on sacrificial blankets and helmets of the Ob Ugrians (Gemuev, Baulo, 2001: 108, 116, 122, 144). Solar- and lunar-shaped tamgas are also known (Ivanov, 1954: 32, fig. 13). Images symbolizing the sun and the moon were clipped out on hides of deer that were sacrificed to a particular god (Ibid.: 81–82; Kharyuchi, 2012: 15–16). It should be noted that all such signs were associated with images of deer or horsemen. In this respect, the Shuryshkary plaque shows a unique composition of the solar and lunar symbols associated with an anthropomorphic image.

A complicated and ambiguous question arises: where did the scene with the sun and the moon on each side of the head of an anthropomorphic character come to northwestern Siberia from? This issue has been comprehensively discussed by A.V. Baulo and I.N. Gemuev (Gemuev, Baulo, 2001: 19–22; Baulo, 2004: 38–44). Baulo identified three main conceptual stages in the history of the existence of imported silver vessels in the 5th–7th centuries in northern Siberia: identification, utilization, and impact (2004: 36). The scene of a horseman with a hawk discussed by Baulo and Gemuev represents the clearest example of this notion. This scene was firstly identified on the eastern goods; subsequently, the hawker image was repeatedly reproduced on plaques, and has survived till today in the form of images on Ob-Ugrian sacrificial blankets. The signs of the sun and the moon emerged in West Siberian art as early as in the 8th–9th centuries, while plaques with hawker images are dated to the 12th–14th centuries. Apparently, one more scene, apart from a “horseman with a hawk”, produced an impact on the local culture. The case in point is the images of divine characters holding sun and moon in their hands. From our point of view, speculations about possible borrowings from rather distant cultures should be based on, firstly, availability to local artisans of goods with a particular scene; and, secondly, opportunity for these artisans to communicate with the people bearing knowledge about the depicted characters. The latter condition seems problematic, especially in the sense of getting any profound knowledge about the depicted characters. However, even the simple idea that a particular character represented an important deity and his belongings were also divine, might force the artisan to use such signs in order to impart these divine features to the new images typical of the local, West Siberian cultures.

An anthropomorphic divine character holding the sun in one hand and the moon in another is shown on four Chorasmian bowls of the 6th–7th and the first half of the 8th centuries (Darkevich, 1976: 106, 107; Marschak, 1986: Abb. 86). These bowls were discovered in the Perm Cis-Ural region, i.e. they could have been known by the artisan who made the Shuryshkary plaque. A goddess is shown holding the sun in her right hand and the moon in her left hand on three bowls, vice versa on the 4th bowl.

The engraved images on the Shuryshkary plaque are mostly illegible, except for the facial image, to which several parallels could be mentioned. The rounded face with big round eyes is shown among the images engraved on the Iranian bronze bowl deposited in the Yamalo-Nenets Regional Museum Complex of I.S. Shemanovsky (Fedorova, 2014: 95). The nose and eyebrows on the plaque are shown through two curved lines, while those on the bowl are shown through five vertical straight linesegments. Dancing heroes engraved on the scoop from Kotsky Town (Khanty-Mansi Autonomous District) are shown with rectangular mouths, with three short lines running from the their ends (Leshchenko, 1976: 182).

Another group of artifacts, which show similarity to the images of the anthropomorphic character and the engraved face, is represented by the so-called anthropomorphic dolls with faces, which are located in fur bags (for details see (Karacharov, 2002)). The author of this publication follows other researchers and attributes the dolls to burial- and funeral-rites (Ibid.: 45–49). In the context of our study of parallels to the Shuryshkary plaque, the following is important: 1) all well-preserved wooden and bronze faces show traces of human hair with bronze pendants and plait decorations, attached to helmet tops (Ibid.: 29–44), which is similar to the position of plaited hair with decorations on the Shuryshkary plaque;

-

2) wooden faces from the Ostyatsky Zhivets settlement show and original design of the mouth with short lines diverging from it, similar to those observed on the face engraved on the Shuryshkary plaque.

Date and place of manufacture of the plaque

The age of the Shuryshkary plaque can be estimated on the basis of available analogues, though most of them represent incidental finds without archaeological context. V.N. Chernetsov attributed the Berezov plaque to the Orontur stage of the Lower Ob culture dating to the 6th– 9th centuries. N.V. Fedorova attributed the Shuryshkary plaque bearing three anthropomorphic characters, as well as other similar artifacts, to the 10th–12th centuries (Sokrovishcha Priobya. Zapadnaya Sibir…, 2003: 87). Cast images mentioned above as the analogues to the Shuryshkary characters have also been dated to the 10th– 12th centuries. Apparently the plaque was manufactured during that period. It is likely that all plaques bearing the images of humans and of fantastic animals and birds were produced in a single center. This assumption is supported by the noticeable similarities in the iconography of characters, ornamentation and general patterns of the objects, and also techniques (good silver and white bronze casting, accurate polishing of surfaces, hangingloop which was initially connected to the upper part of the plaque, where later an opening was drilled). Nearly all round plaques with cast decoration, excluding the plaque with a griffin-image from a hoard in the Tazovsky District, YNAD, were discovered in the basins of the Severnaya Sosva and Synya rivers and in vicinity to Lake Shuryshkarsky Sor, i.e. in a comparatively small area in the western Lower Ob region.

Up to the present, there have been no reliable data as to whether this region was the center of manufacture for plaques and other similar articles, or whether it was the place where the main customers for these goods lived. The question is not meaningless, because no traces of a significant medieval foundry have been found in northwestern Siberia so far. The only exceptions are the remains of the so-called Tazovsky jewelry-workshop (Khlobystin, Ovsyannikov, 1971), Rachevsky productionworkshop (Terekhova, 1986: 114–123), and a foundry uncovered at the archaeological site of Zeleny Yar (Zeleny Yar…, 2005: 25–30). Notably, Tazovsky and Rachevsky workshops have been dated to roughly the same period as the plaques. However, practically no molds have been found at the workshops, except the Rachevsky workshop that yielded pendant casting molds. Hence, correlations of particular products with the workshops are hardly possible. The hypothesis on the existence of the local bronze casting-works in northwestern Siberia is based on two facts:

-

1) traces of such works, dating to the turn of the eras, have been noted at the ancient sanctuary Ust-Polui (YNAD) (Gusev, Fedorova, 2012: 23);

-

2) in the late 1st–early 2nd millennia AD, statusmarking ornaments were cast in series (six to eight items) in one mold, which suggests mass production of such ornaments (Baulo, 2011: 185, fig. 285, 286; Fedorova, Sotrueva, 2010: 49; Sokrovishcha Priobya v Osoboi Kladovoi…, 2011).

It cannot be excluded that foundrymen moved from place to place within the said region, to fulfill the orders of various customers. In our view, the remains of the jewelry-workshop in the Taz River basin suggest exactly this practice (Kholbystin, Ovsyannikov, 1971: 248–257). One more point about the manufacturing center: it could hardly be located in the Cis-Urals, where a number of well-developed bronze-casting and jewelry-workshops existed (Belavin, Krylasova, 2008: 502). This is because “plaque-like” articles have not been recorded in the Cis-Urals. In the early 2nd millennium AD, numerous round plaques were produced of thin silver or bronze plates there. The area of distribution of these artifacts is comparatively well established. Numerous plaques made of plates were reported from the Trans-Urals and the Lower Ob region. Such plaques of plates have one feature in common with cast plaques: both are big round plaques with a hanging-loop or opening.

How exactly the round plaques were worn and used is not quite clear. Taking into account their shape and decorative motifs, we can assume that the plaques were hung as pendants on the chest. A big round plaque was discovered on the chest of the buried individual in the tomb dating to the Kulai period (Borzunov, Chemyakin, 2006: 103). Roughly the same age as the plaques in question has been proposed for a series of (mostly sitting and some standing) anthropomorphic figurines made of backed clay. The characters wear fur coats with ornamentation, and some of them have personal adornments (Ugorskoye naslediye…, 1994: 74, fig. 21). Some figurines show images of large round plaques on their chests (Ibid.: 74; Viktorova, 2008: 142; Pristupa, 2008: 42, 83; Chikunova, 2014: 56, fig. 5, 2 ; p. 58, fig. 7, 10 , 13 ). I.Y. Chikunova has identified several areas of distribution of clay figurines, and made an important remark that the northern area of distribution revealed the greatest number of figurines with images of round plaques (2014: 62).

Available data on modern Ob-Ugrian cult-practices provide additional information on ways of wearing the round plaques during the Middle Ages. A few images are known, representing local gods and guardian spirits wearing small silver or copper saucers hanging on their chests (Baulo, 2009: 10, 13). Plaque-pendants and mirrors were used in burial-practices by the population that has left several burial grounds in the Lower Ob dating to the 19th century (Murashko, Krenke, 2001:

55). Researchers point out that such plaques were mostly used as “adornments and amulets. Apparently, the plaques were placed over the hearts of the buried men exactly as amulets… Plaques made of copper alloys were found in 162 tombs, while the total number of the uncovered plaques is 560” (Ibid.).

Conclusions

The plaque representing a human-like character with two birds and solar and lunar signs on each side of the head belongs to the comparatively numerous group of cast bronze and silver plaques with anthropomorphic images (5 pcs), fantastic animals (griffins) and other imaginary characters (8 pcs), and carnivorous birds (5 pcs). One plaque shows a scene with a spread-eagled bear image, fish, and two snakes; another plaque shows a reindeer image. Articles’ diameter varies from 6.3 to 16.8 cm, but the most typical plaque-diameters are around 10–11 cm. At present, 20 plaques dating to the 10th–12th centuries are known.

The design of the plaques and the iconography of the characters are very close. Similar techniques were used in forming plaque-edges (twisted and double lines, or line of “pearls”), representing anthropomorphic characters in frontal view, with disproportionally big heads in helmets and facial masks, with highlighted shoulder lines, and other features. Birds, excluding owls, were always shown in side-view, with big beaks and claws, and uplifted wings (possibly to stress their aggressive mood).

These plaques were mostly spread over northwestern Siberia. Most such plaques were parts of hoards, or medieval and modern sanctuaries, of Ob Ugrians. Only three plaques (with representations of owl and griffin) were uncovered from the tombs of the Saigatinsky IV and VI burial grounds. The likely place of manufacture of the plaques is the northeastern Urals or the northwestern Ob basin.