Representations of paired horse heads in Yakut art: past and present

Автор: Alekseyev A.N., Crubzy E.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.44, 2016 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145145265

IDR: 145145265 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2016.44.2.091-101

Текст статьи Representations of paired horse heads in Yakut art: past and present

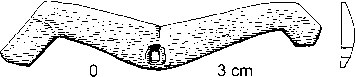

In 1986, in the basin of the Olekma River, A.N. Alekseyev discovered the settlement of Ulakhan Segelennyakh, where 15 habitation layers from the Neolithic to the Late Middle Ages have been identified. The location of the site, its stratigraphy, and the discovered cultural remains have been described in detail in the book by the author of the present article (Alekseyev, 1996: 12–14). The medieval layer 4b contained a curved bone plate with a profile representation of two horse heads turned with their muzzles in opposite directions (Fig. 1, 1). Its length is 7.4 cm; its width is 1.5–2.0 cm, and its thickness is 0.15 cm. A biconical hole, probably intended for wearing the pendant on a cord, is located in the middle of the plate, at the point of its bend. The same habitation layer contained fragments of bones, including a fragment of a metacarpal bone belonging to Bos/Bison (definition by Dr. G.G. Boeskorov). In all likelihood, they belonged to a domestic bull. The petroglyph site of Suruktaakh Khaiya with representations of four bulls and a horse painted with red ochre and dated to the Paleolithic, is located not far from the village of Ulakhan Segelennyakh (Mazin, 1976; Okladnikov, Mazin, 1976: 47–49, 150; Kochmar,

3 cm

0 3 cm

0 3 cm

3 cm

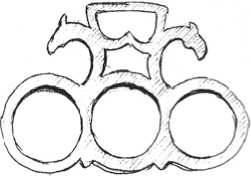

Fig. 1. Bone and bronze (copper) pendant-amulets and clasps. Photograph by T.B. Simokaitis.

1 – Ulakhan Segelennyakh (bone); 2 , 3 – Ordzhogon-2 (bone); 4 – village of Chymnai (bronze, copper?); 5 – village of Chkalov (bronze); 6 – village of Suntar (bronze?).

1994: 134–135). However, in the light of recent research it is possible that these representations might have been left by the inhabitants of the Ulakhan Segelennyakh settlement in the first millennium AD.

A bone plate with representations of horse heads, which was found at that site, belongs to the group of artifacts which archaeologists call “horse amulets”, “paired horse heads”, “horse-pendants”, “doubleheaded horses”, simply “horses”, etc. An established terminology for their designation does not exist. This “wandering” motif is not uncommon among the antiquities of Siberia and Central Asia. It widely occurs in diverse forms in the circle of Finno-Ugric and Northern Russian cultures. The study of archaeological and ethnographic sources, objects from museum collections, as well as architectural elements of buildings and structures shows that this motif follows a longstanding and stable tradition in Yakutia.

Double-headed horses from the archaeological sites and museums of Yakutia

The artifacts which we describe below represent a variety of objects and structures produced for various functional purposes. They also differ in terms of the material of which they were made (bone, metal, or wood), and are grouped accordingly.

Bone. The Sakha-French archaeological expedition, which excavated old Yakut burials in the Vilyuy basin, discovered bone plates similar to the find from Ulakhan Segelennyakh. A slightly curved plate with profile representations of two horse heads with their muzzles turned in opposite directions was found in the burial of Ordzhogon-2 (Nyurbinsky Ulus of the Sakha Republic), dating to the 17th–18th centuries (Fig. 1, 2). The entire plate was carved of mammoth’s tusk and was a part of a belt buckle or a pendant decorating a belt (Crubézy et al., 2012: 193). Another horse-pendant from the burial of Ordzhogon-2 is a strongly curved bone plate with a hole in the middle and cogged design on both ends (Fig. 1, 3). Horse heads are not marked on the plate, but plates lacking even stylized representations of horse heads at the ends also occur at the archaeological sites of the Khakass-Minusinsk Hollow (Vadetskaya, 1999: Fig. 69, 76; Mitko, 2007: Fig. 19, 22, 10).

Metal. The majority of the objects with representations of paired horse heads were made of copper, bronze, silver, or iron. Almost all of them are varieties of pendants (amulets, adornments of ritual vessels, etc.) and can be divided into seven types.

Type 1. This type is represented by a pendant which was found by A.I. Markova on a plowed field in the vicinity of Chymnai village in Tattinsky Ulus of the Sakha Republic and subsequently transferred to the History Museum at the North-Eastern Federal University, where it is kept now. The pendant was made of bronze or copper plate. In the middle it has a hole for suspending on a cord, and a spur-like protrusion above the hole in the place where the plate is curved (Fig. 1, 4). Such protrusions occur on some Tagar specimens. The Yakut pendant looks very similar to Tashtyk pendants, but these are distinguished by the manufacturing techniques. It is known that Tashtyk horse-plates were mostly cut out of bronze sheets, while the amulet from Chymnai was made using the casting method just like Tagar pendants with which it should be associated.

A similar pendant is kept in the collection of the Museum of Local History in the village of Chkalov in Khangalassky Ulus of the Sakha Republic. According to some reports, it once belonged to the family of the well-known Yakut historian and ethnographer, G. Ksenofontov. The pendant is a narrow curved plate with a profile representation of two horse heads and a hole at the place of the curve (Fig. 1, 5 ). It is made of bronze or copper using the casting method. Like the previous pendant, it was apparently an apotropaic amulet which is similar to Tagar specimens.

Another horse-pendant can be found in the collection of the Museum of Secondary School No. 1 in the village of Suntar, where it is exhibited as a part of the festive decoration of a bride’s horse in a wedding horse cortege (Fig. 1, 6 ). The exhibit passport indicates that the pendant was cast of bronze or copper by an unknown artisan in the late 19th century. This object is larger than the amulets mentioned above; its length is 12 cm. Two spurlike protrusions are located in the place where the plate curves . The Tashtyk collections contain specimens with similar design which L.R. Kyzlasov interpreted as a profile representation of a saddle (1960: 91, fig. 32, 5 ). It is possible that spur-like protrusions on the Suntar pendant also designate the saddle, even more so since the pendant, first of all, is the adornment of the girth strap and thus is directly associated with the harness, and second of all, because there exist some examples where the Yakut artisans of the 18th–19th centuries depicted saddles in a similar manner (Fig. 2).

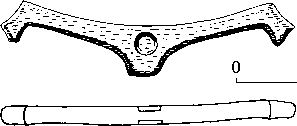

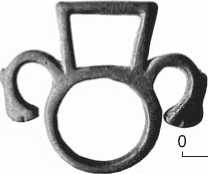

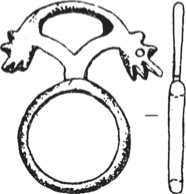

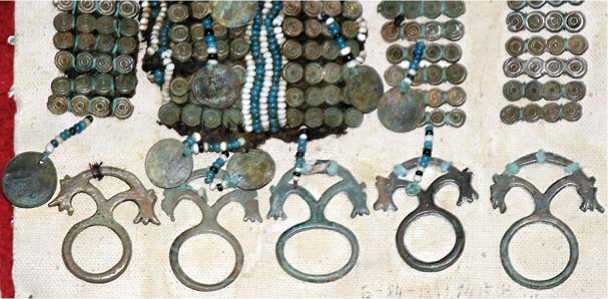

Type 2. All six known pendants of this type are ring buckles with horses (Fig. 3). These pendants decorated ritual leather vessels, siri isit, used for producing and storing koumiss, as can be seen in photographs of the late 19th–early 20th century (Fig. 4).The photographs show not an everyday, but a ritual koumiss vessel which is used in the traditional Yakut festival, Yhyakh. This festival is dedicated to the summer solstice and the heavenly patron deities of people and cattle, and therefore the ring in the pendants of type 2 may symbolize the sun. As a rule, buckles with horses decorate ritual vessels, burial clothes, and other special objects, which indicates that ring buckles with representations of horse heads are attributes of the ritual complex and are associated with Yakut myths about the birth of the solar horse.

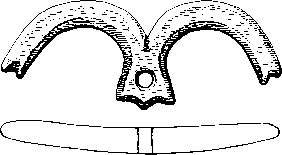

Type 3. This type is represented by double-ring buckles with horses (Fig. 5). One buckle from the collection of the Yaroslavsky Yakutsk State Museum of History and Culture of the Northern Peoples differs from all the others: the horse heads on this buckle are linked by their bridles with the rings, which symbolizes the connection of the horses with the sun (Fig. 5, 2). These rings on another buckle of this type have two ear-like protrusions with vertical grooves (Fig. 5, 3). The filling of the grooves has partially preserved shiny tin-silver inclusions. The earlike protrusions with shiny cannelures might have once symbolized the rays of the sun in the spirit of the story of the horse begotten by the sun.

According to their purpose, the buckles of type 3 are divided into two groups: adornments of ritual koumiss vessels and buckles for decorating festive female belts (Kulturnoye naslediye…, 1994: Photograph 110). The latter constitute the main bulk of pendants appearing in the collections of museums of the Sakha Republic. Buckles for koumiss vessels were made of bronze or copper, imitating gold. Female waist adornments were mostly made of silver, although sometimes copper objects were found. Silver was quite popular in the Yakut society and was often valued more than gold, because unlike gold it was considered to be a “clean” metal. A

3 cm

Fig. 2. Cast bronze pendant of a male belt. The figurine of a saddled horse. 19th century. Museum of Local History of the Nyurbinsky Ulus. Photograph by I.E. Vasiliev.

0 3 cm 0 3 cm

Fig. 3. Metal ring buckles.

1 – copper buckle (village of Oktemtsy, Yakutia); 2 – buckle-pendant (copper, bronze?) of a ritual koumiss vessel. Museum of Local History of the Maiya village, Megino-Kangalassky Ulus (Yakutia). Photographs by V.G. Popov; 3 – bronze buckle from the Ivolga burial ground (Buryatia) (after (Davydova, 1996: Pl. 36, 3 )).

Fig. 4. Ritual leather vessel, siri isit , decorated with pendants of horse figurines (copper, bronze?). Late 19th–early 20th century. Photograph by A.P. Kurochkin (after (Vizualnoye

naslediye…, 2011: 66)).

detail, similar to that which we mentioned above while describing type 1 (a spur-like protrusion between the rings), sometimes appears on the female pendants (see Fig. 1, 4 ).

Type 4 . Buckles with three rings belong to this type. According to their functional purpose, they can also be divided into adornments of koumiss vessels and adornments of festive female belts. The first group includes a massive brass buckle with spear-shaped pendants on the rings (Fig. 6, 1 ). Other buckles of this type do not have such a decoration.

Pendants of the second group were first found by F.M. Zykov from the Institute of Language, Literature, and History of the Yakut Branch of the USSR Academy of Sciences during the 1987 field trip to the Taimyr Peninsula for studying folklore and ethnography of the Yakut-speaking Dolgans. The hand-written report on the expedition (Zykov, 1987) contains several drawings of pendants with a note that they were found in the village of Syndassko on the Taimyr Peninsula. One of the pendants has spur-like protrusions between the rings, similar to some pendants of types 1 and 3 (Fig. 6, 2). With the help of A.A. Barbolina and N.S. Kudryakova, and the employees of the Taimyr House of Folk Arts, we were able to get photographs of objects which were a part of female waist adornments (Fig. 6, 3). We can assume that such adornments appeared among the Dolgans as a result of their active cultural interactions with the Yakuts.

Type 5. This type includes buckles with the stylized representations of horse heads having a gryphon-like appearance (Fig. 7). Five of them were found during the excavations of Yakut burials of the 17th–18th centuries in the Gorny (2 spec.) and Oymyakonsky (3 spec.) Uluses of the Sakha Republic (Gogolev, 1990: 92, pl. LI, 1, 5; Bravina, 2015: Fig. 031, 038). Another similar buckle was found by A.V. Everstov in Megino-Kangalassky Ulus among the ruins of an old Yakut dwelling in the location of Dollu Nemyugyute (Fig. 7, 4 ). The outfit with such pendants is a part of the exposition in the Museum of History and Ethnography of the Olenyok village (Fig. 8). All objects of this type were cast of copper.

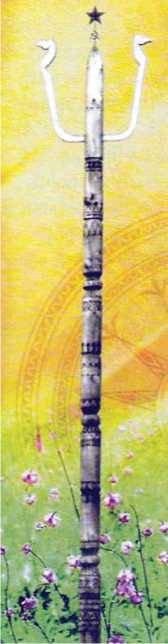

Type 6 . This type includes all varieties of modern festive attributes called Ytyk Duoga : staffs with long handles, decorated with sculpted horse heads. As a rule, they are made of silver, although sometimes specimens of melchior occur. At the opening ceremony of the ethnic festival, Yhyakh, the master of the festival, usually an honorable elder or a head of the settlement, sets the Ytyk

Fig. 5. Double-ring buckles with horses. Photograph by P.R. Nogovitsyn.

1 – female waist adornment (copper, silver). Museum of Local History of the Churapcha village, Churapchinsky Ulus; 2 – pendant of a ritual koumiss vessel (copper?). Yakutsk State Museum of History and Culture of the Northern Peoples; 3 – buckle-pendant with ear-like protrusions and vertical cannelures. Museum of Local History of the Maiya village, Megino-Kangalassky Ulus (Yakutia).

Fig. 6. Buckles with three rings.

1 – buckle with pendants (copper). Museum of Local History of the Maiya village, Megino-Kangalassky Ulus (Yakutia). Photograph by V.G. Popov; 2 – pendant from the village of Syndassko, Taimyr (after (Zykov, 1987)); 3 – female waist adornments of the Dolgans, Taimyr. Photograph by A.A. Barbolina and N.S. Kudryakova.

0 3 cm

0 2 cm

Fig. 7. Buckles with stylized images of horse heads from the archaeological monuments of Yakutia.

1 , 2 – from the burial of the 17th–18th centuries, Gorny Ulus (after (Gogolev, 1990: Pl. LI, 1, 5 )); 3 – from the burial of Obyuge I, Oimyakonsky Ulus (after (Bravina, 2015: Fig. 031)); 4 – from the ruins of an old Yakut dwelling. Find by A.V. Everstov. Photograph by V.G. Popov.

Fig. 8. Copper pendants of a waist adornment from a Late Medieval burial. Museum of History and Ethnography of the Olenyok village. Photograph by R.I. Bravina and V.M. Dyakonov.

Duoga upon the top of the serge ritual post (Fig. 9), which designates the beginning of the festival.

Type 7 . This type includes the pommel of the batyia knife, a piercing-and-cutting close combat weapon from the collection of the Yaroslavsky Yakutsk State Museum

Fig. 9. Ritual of setting up the

Ytyk Duoga staff on the serge ritual hitching post (after (Ysyakh Olonkho, 2012: 222)).

0 3 cm

Fig. 10. Handle of a

Yakut batyia, close combat weapon. Yakutsk State Museum of History and Culture of Northern Peoples. Photograph by

V.G. Popov.

of History and Culture of Northern Peoples , modeled in the form of horses (Fig. 10).

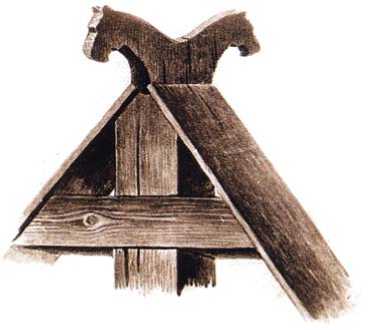

Wood. Most often, wooden double-headed horses are a part of the architectural decoration of structures, associated with ritual purposes. For example, they decorate the entrance to the place where the Yhyakh festival is held (Fig. 11). Horses also decorate the tyusyulge , set up at these locations (Fig. 12), the entranceway, and frames of doors and windows in the houses, where ethnic rituals are performed (Fig. 13), as well as ritual hitching posts called serge (Fig. 14), grave structures at cemeteries (Fig. 15), and old Yakut calendars (Fig. 16).

Completing the description of items with representations of horse heads, we should note that various types of pendants with horses are kept in museums not only in the Sakha Republic, but also in other Russian and international museums, such as, for example, the M.B. Shatilov Tomsk Regional Museum of Local History, the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, etc.

Discussion

The cult of the horse is widespread in the cultures of the Eurasian nomads. Its various manifestations among the Yakuts have been studied by Y.I. Lindenau (1983), V.L. Seroshevsky (1993), R.K. Maak (1994), I.D. Novgorodov (1955), I.V. Konstantinov (1971), L.P. Potapov (1977), A.I. Gogolev (1993), R.I. Bravina (1996; Bravina, Popov, 2008), and other scholars. Without

Fig. 11. Yhyakh Olonkho, Mirny, 2011 Accessed April 25, 2015).

Fig. 12. A tyusyulge which is set in the location of the ethnic festival of Yhyakh.

Yakutsk State Museum of History and Culture of the Northern Peoples. Photograph by I.E. Vasiliev.

Fig. 13. Examples of architectural design with wooden paired horse heads.

1 – door frames of the house where the rituals are performed, Vilyuysk. Photograph by P.P. Petrov; 2 – the entrance group of the Aiyy ritual house, Yakutsk (after (Yakuty (sakha), 2013: 371)).

Fig. 14. Yakut serge, ritual hitching posts.

1 – Suntarsky Ulus (after (Fedorova, 2012: Fig. 60)); 2 – Vilyuysk. Photograph by P.P. Petrov; 3 – Ust-Aldansky Ulus (after (Ysyakh Olonkho, 2012: 130)).

Fig. 15. Upper part of the grave structure of the 19th century (after (Osnovopolozhnik…, 2003: 22)).

Fig. 16. Yakut calendars of the 19th century (http://diaspora. shtml. Accessed April 28, 2016).

Fig. 17. Hitching posts, set at the burial-place of the sacrificial horse.

1 – The “Aal Luuk Mas” world tree (after (Yakuty (sakha), 2013: 316)); 2 , 3 – the “Ebyuge sergete” hitching posts (after (Bravina, Popov, 2008: Fig. 19, b , d )).

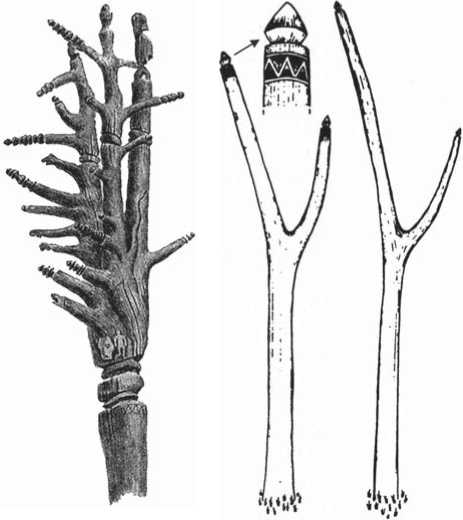

reviewing each author’s position with regard to the notion of the “cult of the horse”, we should note that his or her studies contain ample information about the ritual role of the horse in Yakut art. We would like to add another little-known fact. In the book on the cult of the horse among the Turkic-speaking tribes of the Central Asia, S.P. Nesterov presented drawings of the Karasuk period from the petroglyphic site in the Khakass-Minusinsk Hollow, depicting horses near vertical posts with forked tops. Agreeing with the opinion of Y.A. Sher and N.V. Leontiev, he believed that such compositions depicted the sacrifice of the horse at the world tree (Nesterov, 1990: 111–113, fig. 27). In this regard, we should note that there exist similar wooden posts in Yakutia, which symbolize the world tree and are called khoolduga am sergete— “a hitching post of the sacrificial horse” (Fig. 17, 1 ). Archaeologists find the remains of forked hitching posts, serge (Gogolev, 1990: 88). Most often, they are installed near the burials of humans with horses, that is, in the places where the horses were sacrificed, like in the motif of the Karasuk petroglyphic site in Khakassia (Fig. 17, 2 ). Hitching posts somewhat changed over time: they came to be made of whole logs, and the forked top became decorated; but in fact it is the same forked post for the sacrificial horse, which retained its ritual purpose (Fig. 17, 3 ). The Yakuts make them today as well, perceiving them as a symbolic representation of the world tree and hitching posts of heavenly horses (see Fig. 14, 2 ).

Thus, the interpretation of compositions with horses at the Karasuk petroglyphic site in the Khakass-Minusinsk Hollow as the scenes of horse sacrifice at the world tree finds its confirmation in the ethnographic culture of the Yakuts, and seems to be entirely justified.

The artifacts in the form of doubleheaded horses described above are undoubtedly associated with the cult of the horse. The earliest artifact is a bone pendantamulet found at the settlement of Ulakhan Segelennyakh in layer 4b with a radiocarbon date of 1510 ± 140 BP (GIN-78392), corresponding to a calendar date of 200– 900 AD (Stepanov et al., 2012: 625). The results of dating the underlying and overlying cultural layers make it possible to somewhat narrow this wide chronological range. The upper chronological boundary of the 5th layer is mid-4th century AD, and the lower chronological boundary of the layer 4a is 9th century AD. Taking into account these dates and the stratigraphic situation, we may assume that layer 4b containing the pendant in the form of the double-headed horse belongs to the second half of the 4th–8th centuries AD.

The amulet from Ulakhan Segelennyakh shows similarities to some pendants from the Ivolga burial ground in the Trans-Baikal region, which A.V. Davydova described as bent-beam (1985: Fig. 16, 4 , 7 ; 1996: Pl. 6, 6 ; Pl. 39, 28 ): the plates are flat, gently curved; the heads are rendered in a simplified form. However, the pendants from the Ivolga burial ground are made of stone (chalcedony and clay slate), while the Yakut pendant is made of bone. Indeed, the materials could be very different. Bronze double-headed horses first appeared in Central Asia as early as the Scythian Age. In the period of the Xiongnu strengthening, such objects received wide circulation and were marked by diverse style and materials. The Xiongnu had bronze double-headed horses, while in the Khakass-Minusinsk Hollow such horses of bronze, wood, and bone were found.

Bronze ring buckles representing animal heads were also discovered at the Ivolga burial ground (Davydova, 1996: Pl. 4, 5 ). They are very similar to some Yakut ring buckles with horses (see Fig. 5, 3 ). A Chinese wu shu coin was found at the Ivolga burial ground together with the Xiongnu pendants and buckles which are of interest to our study. A bronze wu shu coin was also found at the settlement of Ulakhan Segelennyakh at the junction of layers 4b and 3, which brings the Yakut and the TransBaikal assemblages even closer together. E.I. Lubo-Lesnichenko (1975) associated the appearance of these coins in Siberia with the Xiongnu expansion at the turn of our era, and D.G. Savinov (2013: 67) figuratively called such coins a kind of “visiting card” of the Xiongnu. Indeed, in Central Asia and Southern Siberia, wu shu coins often occur among the materials of sites associated with the Xiongnu. Probably, in Yakutia, they may also mark the presence of the Xiongnu cultural component in an archaeological assemblage. As far as the similarities in the material culture of the Xiongnu and the Yakuts are concerned, it is interesting to note that the Yakuts had balkhakh vessels in the form of a vase with a flat bottom, the body of which was decorated with vertical groovecannelures. A very similar vase with vertical cannelures appears in the assemblage from the Ivolga burial ground (Davydova, 1985: Fig. XVI, 17 ). According to Alekseyev, this parallel may indicate a Xiongnu trace in the cultural genesis of the Yakuts (2015: 58, fig. 7).

These comparisons show that the original forms of Yakut pendants may be associated with the culture of the Xiongnu in the Trans-Baikal region and Mongolia. From there, by cultural “relay race” they reached the northern borders of the nomadic world. Many scholars have long noted various manifestations of the Xiongnu cultural component in the cultural genesis of the Yakuts (Bernshtam, 1935; Ksenofontov, 1937: 460–461, 470– 473; Ivanov S.V., 1975; Vasiliev, 1982; Sidorov, 1985; Gogolev, 1993: 26–29; Bravina, 1996: 63; Yokhansen, 2012; Alekseyev, 2013; and others). The well-known specialist on the medieval history of Siberia, Savinov believes that the Xiongnu-Xianbei layer in the Yakut ethnic genesis is expressed more clearly than the Scytho-Siberian or Old Turkic layers (2010, 2013). Thus, the hypothesis of the Xiongnu roots of the Yakut representations of paired horse heads seems to be most plausible.

Some pendant-horses from Yakutia have parallels among the antiquities from the Khakass-Minusinsk Hollow; for example, copper-bronze amulets (see Fig. 1, 4–6 ) are very similar to Tagar and Tashtyk specimens. Bone amulets from the burial of Ordzhogon-2 on the Vilyuy River (see Fig. 1, 2 , 3 ) may also have Yenisei roots. It is possible that such pendants were common among the tribe of the Kyrgys which, according to the Yakut historical legends and genealogies, lived in Yakutia even before the arrival of the southern ancestors of the Yakuts to the area. People of this tribe bred horses and horned cattle; when one of the tribesmen died, he was cremated. The rite of cremation existed among the Yenisei Kyrgyz. Their ethnic name is consonant with the name of the Yakut tribe of Kyrgys, thus some scholars associate these ethnic groups with the migrations of the Kyrgyz from the Yenisei. Over time, some of them died, and the rest became a part of the emerging Yakut people; from them the clan of Yakut-Kyrgys at Kobyaysky Ulus emerged (Sakha…, 1960: 123; Ivanov M.S., 1980; Bolo, 1994: 84; Zakharov, 2005: 22–23). The Khakass-Yakut cultural and historical ties, which once existed, are reflected in the material and spiritual culture in the form of many different parallels well-studied by generations of scholars (see the historiography in (Gogolev, 1993: 54–57; Savinov, 2013)). Bone pendants from the burial of Ordzhogon-2 may have also been an echo of the Khakass-Yakut cultural and ethnic contacts in the Late Middle Ages. It can be established more definitively only after additional research.

The purpose of the double-headed horses still remains not entirely clear. They mainly occur in the grave goods of the Yakut burials of the 17th–19th centuries. In the regions neighboring Yakutia, doubleheaded horses are often found in the graves of the Xiongnu, the burial mounds of the Tagars, in the tombs of the Tashtyks, etc. At the same time, horse symbolism had some importance in the world of the living, where, judging by the Yakut materials, it served as an attribute of ritual objects, such as koumiss vessels. In this respect, we should mention in particular ring buckles with horses, which are clearly associated with the myths about the birth of the solar horse. According to some Yakut legends, heavenly deities first created the horse; from the first horse, a half-horse-half-human was born, and only then was man born, which means that the horse is the zoomorphic ancestor of man (Emelianov, 1980: 33, 36, 38; Reshetnikova, 2013). According to another version, the pantheon of the Yakut heavenly deities includes Solar Dzhesegey Toyon, the creator and patron of horses, and Yuryung Aar Toyon, the First Creator of man. Therefore, the belief that horses were begotten by the sun, the solar deity Dzhesegey, became a part of the traditional worldview of the Yakuts, and thus there is a common expression, “the solar Dzhesegey horses”. The ritual siri isit koumiss vessels with double-headed pendants were used during the ritual koumiss drinking, the sacred ritual at the festival of Yhyakh, dedicated to the heavenly deities, the protectors of people and cattle, where Dzhesegey was one of the main deities. In this regard, it can be assumed that ring pendants of the siri isit koumiss vessels represented the motif of birth of the horse from the heavenly host, which is most clearly evidenced by the buckle, where the images of horse heads and rings are linked with bridles (see Fig. 5, 2).

Currently, double-headed horses have lost their former sacred meaning and are used by jewelers, architects, and designers in the most ordinary things, unrelated or almost unrelated to the world of the dead. In general, it is important to note that this motif not only survived, but is sufficiently widespread in the contemporary culture of the Yakuts as an echo of their long-standing culture and history.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the employees of the Institute for Humanities Research and Indigenous Studies of the North of SB RAS, I.E. Vasiliev, V.G. Popov, T.B. Simokaitis, A.D. Stepanov, A.I. Kharitonov and the teacher of the Oi Secondary School, P.R. Nogovitsin, for their help in preparing the illustrations.