Revisiting the “Goods Of Kisterna” in Mani, southern Peloponnese. A complicated yet captivating storyline

Автор: Germanidou S.

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: Периферия Византийского мира. Проблемы истории и культуры

Статья в выпуске: 6 т.28, 2023 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article reconsiders the textual and archaeological evidence on the delimitation and, most importantly, on the naming and the praised “goods” around or in “Kisterna”, a still disputable area situated in the NW (Messinia province) or southern (Laconia province) Mani peninsula. These are a Venetian document, as well as the French and Greek versions of “Chronicle of Morea”, the historical works of George Pachymeres, Nikephorus Gregoras, Makarios Melissenos and archaeological heritage, that is, the castle of Leuktro in Stoupa, Oriokastro in Ano Poula, Tainaro cape in Kinsternes bay. According to the interpretation introduced, the regional landscape and topography, the naming could potentially be associated with cisterns and basins where sh by-products preservation and processing was taken place. These workshops were known from the Roman period as cetariae and probably as “lakkoi” in the Byzantine era. The article by its structure includes the parts “Introduction - Aims”, “Deconstructing a) the term and the reason of the “theme” and “Deconstructing b) the naming”, “Revisiting a) the primary sources” and “Revisiting b) the archaeological evidence” as well as “Conclusions”.

Kisterna, mani, messinia, laconia, slavs melings, franks, leuktro-beaufort, tainaro, ketaria-cetariae, cisterns-fish tanks, chronicle of morea, george pachymeres, nikephoros gregoras, makarios melissenos

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149144512

IDR: 149144512 | УДК: 94(495):904 | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2023.6.17

Текст научной статьи Revisiting the “Goods Of Kisterna” in Mani, southern Peloponnese. A complicated yet captivating storyline

DOI:

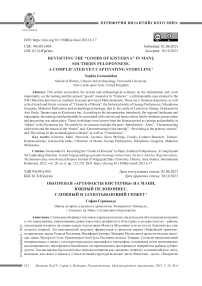

Introduction – Aims. Hardly does any scholar who has engaged with the turbulent history, the intriguing archaeology, and the still obscure topography of the Mani peninsula during the late Byzantine period remain unperplexed when it comes to decoding a range of local enigmatic place names [27; 28; 68]. The variation, also, in regional geomorphology and hydro-geology shape an often contradicting physical landscape that adds to this complexity: craggy, rugged terrains alternate with soft plains and terraced valleys; extreme dryness gives place to water-abundant springs and thick vegetation; steep ravines and sharp gorges slope evenly to a flat shoreline (Fig. 1–2) 3. Serving further as a ‘melting pot’ of different ethnicities that co-existed, interacted, or opposed to each other, Mani’s background becomes even more challenging for investigation.

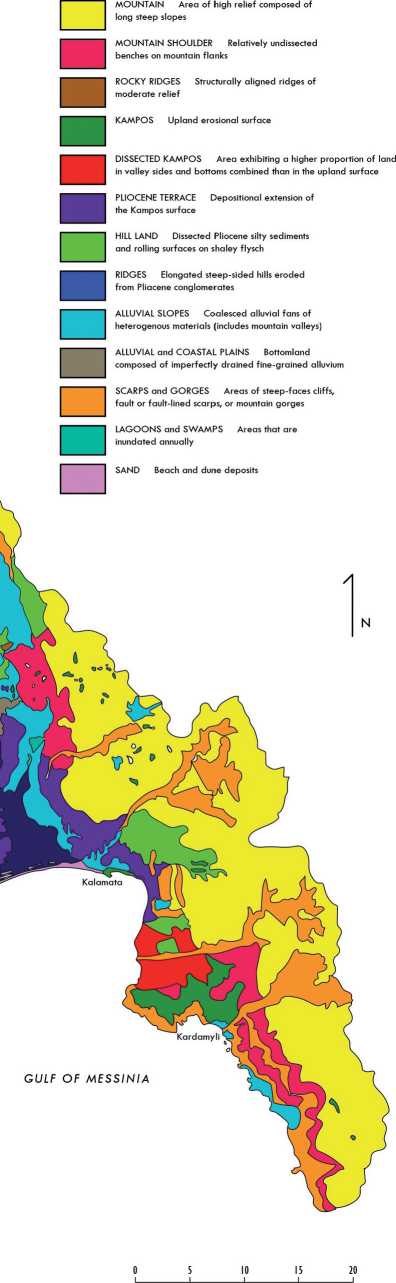

In such a context of cultural and environmental diversity, the location under the designation (the “theme” of or around) “Kisterna”4 ignited a spirit of lasting inquiry regarding its administration status, its boundaries, and the implications of its naming. According to the current state of research, based on a handful of references dated from the end of the 13th century until the end of the 14th century, Kisterna is placed either somewhere in NW Mani, modern day Messinia province (Fig. 3–4), close to the castle of Leuktro in Stoupa 5, or in Ano Poula promontory, at the alleged site of Oriokastro, near Tainaro cape, modern day Laconia province

(Fig. 3, 5–6) [68]. Past scholarship has linked the Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro cape with the 13th – 14th century Kisterna, not, however, without acknowledging the inconsistencies of this assumption (for discussion, see [49]). In any case, sources also imply or state that the Slavs (Melings) were settled in the uplands around Kisterna – a fact for further consideration.

The notable geographical discrepancy between the suggested locations is caused by the ambiguity of their formation conveyed and the lack of details encountered in the written sources. Though it is not the main purpose of this study to focus on framing the exact boundaries of Kisterna, this is a crucial matter that needs to be discussed, even in short. I mostly engage in the definition of the term by George Pachymeres in his History (book Ι, chapter 31), compiled after 1306, where the area around or in Kisterna features as a “theme”, extensive (“elongated”), and abundant in “goods” [21, pp. 122-123]. My primary aim is to decipher, as possible, which these goods might have been through a re-evaluation of little known or overlooked textual references, scarce or understudied archaeological remains, and established or controversial etymologies. The impact of the regional landscape and topography is also considered, although the physical evidence has been densely and heavily altered by modern infrastructure.

Deconstructing a) the term and the reason of the “theme”. According to scholarship, the use of the word “theme”, attested only to Pachymeres, is an anachronism, deprived of its initial and original meaning 6. This holds true because, by the time of Pachymeres, the system of the Byzantine organization into themes had long been abolished, transformed into, and replaced by administrative divisions based predominately on their geography ([4, p. 65] with relevant bibliography on the themes). Moreover, Pachymeres, a learned man, was inclined to use idiomatic words that were outdated and unfamiliar to his peers, often inspired by the ancient past [2]. However, as a state official with access to imperial documents and thus a likely reliable source [38, pp. 33-34], he was hardly unaware of his choice of words. He may have opted for this ‘phantom’ term as the most appropriate to define an extended territory, distinct in its military and fiscal organisation: the “theme” could be an effective option for him to communicate to his readers that the area around or in Kisterna represented somehow more than just a province. Therefore, it must not have been accidentally inserted in his text as just a misconception or simply an archaism.

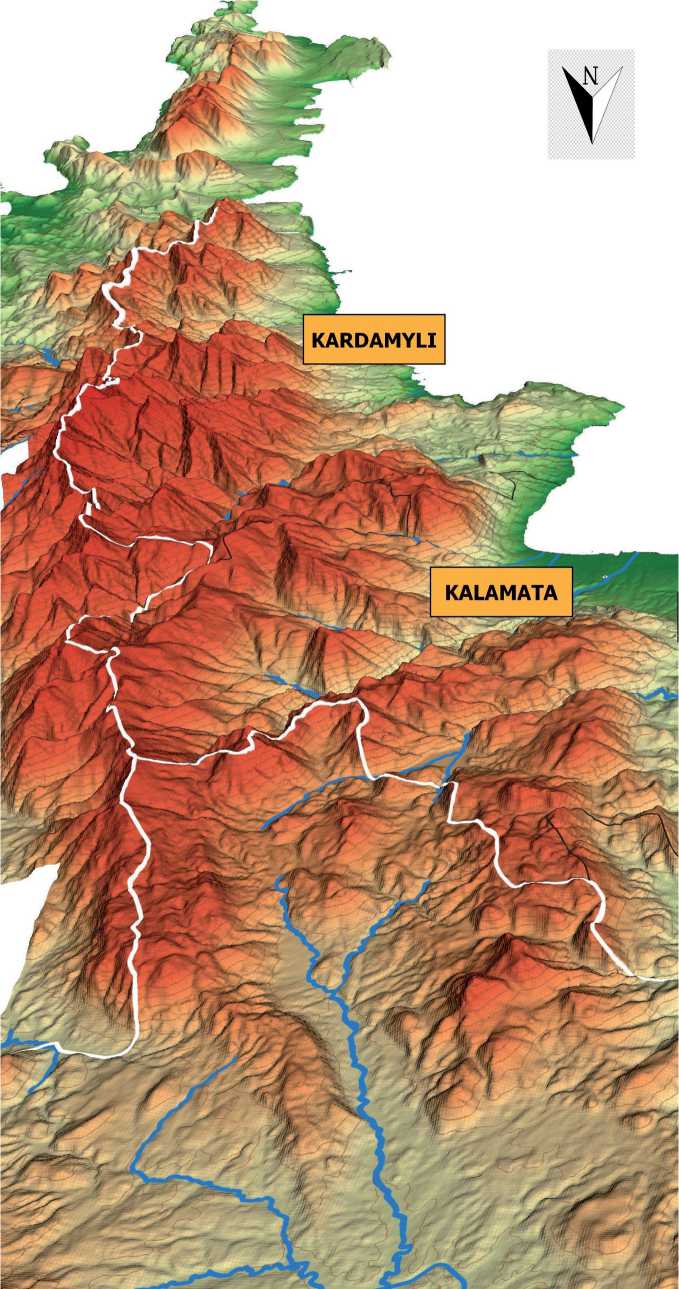

Deconstructing b) the naming. A question that remarkably has not drawn adequate attention is: why was this area called Kisterna? From where did the toponym originate, and from what kind of context? As there is an apparent etymological connection to the Latin word cisterna < cistern, sometimes also used in Byzantine Greek as ‘κ/γι(ν)στέρνα’ alongside the same in meaning word ‘δεξαμενή’, speculations involved the presence of bodies of water, within natural [68, p. 65; 31, p. 67] or constructed configurations [7, p. 504, subn. 5]. Likewise, scholars have argued for the numerous, usually rock-cut, cisterns in Mani, an area of karstic subterrain where water was valuable for storage (Fig. 2). Such hydraulic structures were so crucial for sustaining livelihood that they became a common feature, prevailing in the maniot landscape.

Evidently, Kisterna, due to its etymological and conceptual connotations, alludes to the high number and density of cisterns. That should be undeniable; however, were those cisterns used for water collection and storage, as it is generally accepted? Supposedly, the naming of this area may not be proven that simple but far more complicated than expected.

Revisiting a) the primary sources. In addition to George Pachymeres, Kisterna is cited in a couple of other texts, referring to events that took place during the second half of the 13th century: a Venetian document and the French and Greek versions of the “Chronicle of Morea”. The sources themselves are dated from the end of the 13th century and last almost a century, reaching the end of the 14th century, which coincides with the Frankish occupation of southern Peloponnese.

This restricted timescale demonstrates that the place name equally suddenly appeared and disappeared: nothing was previously known about it, and no collective memory or local oral tradition has survived of it after. There is the exception of Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro, which, however, is a much later, non-official, and alternative appellation, rarely recorded in map registers after the 16th century [32, p. 19].

Here are the relevant citations of Kisterna in their original language (Latin, medieval French, and Byzantine Greek), loosely translated, in the chronological order of the event that they refer to (and not that of the source).

-

1. The Greek version of “Chronicle of Morea” (circa 1340 and 1380) refers to events of circa 1250, when William I Villehardouin, prince (1246–1278) of Morea/Achaia Principality, built a castle named Leuktro (Beaufort by the Franks in Stoupa, Messinia or Oriokastro in Ano Poula, Laconia) on the coast close to Kisterna to subdue the Zygos, the uplands of Taygetos mountain where the Slavs Melings and Ezerites tribes were settled (Fig. 7) ([42, pp. 160-161]; see also [3]). The “Chronicle of Morea” says (lines 3034–3037): “ἂν θέλῃ νὰ ἔχῃ τὸν ζυγὸν ὅλον στὸ θέλημάν του, νὰ ποιήσῃ κάστρο εἰς τὸν αἰγιαλὸν πλησίον τῆς Γιστέρνας....Λεῦτρο τὸ ὠνομάσαν”) [30, pp. 128-129].

-

2. The Greek version of “Chronicle of Morea” refers also to events of the battle of Prinitza (1263–1264), when the byzantine officer Makrynos was sent to the territories of Mani against the Franks. Then the body of the Slavs Melings of Kisterna (Gisterna) was sided with the commander [42, p. 205]. In the Greek Chronicle, it is briefly reported (lines 4593–4594): “ὁ δρόγγος γὰρ τοῦ Μελιγοῦ, τὸ μέρος τῆς Γιστέρνας, ἐκεῖνοι ἐρροβόλεψαν μετὰ τὸν βασιλέα”) [30, p. 192].

-

3. George Pachymeres, referring to events of 1262–1263, makes casual mentions of the castles of Monemvasia, Mani, Geraki, Mystras, the theme all around, or in Kisterna, to the lands that were handed over to the Byzantines to set free the prince William I Villehardouin, captured after the battle of Pelagonia (1259). Pachymeres adds that the theme around or in Kisterna was an extended area with abundance of goods (Book I, chapter 31): “καὶ ἃμα πᾶν τό περὶ τὴν Κινστέρναν θέμα πολύ, γε ὂν τὸ μῆκος καὶ πολλοῖς βρύον τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς” [21, pp. 123.25–26].

-

4. A Venetian document of 1278 furnishes us with information about Slavs, who seized merchandise from Venetian ships with the help of the Byzantines from “Mani”, that is, perhaps, Oitylo in Laconia, Kisterna, and the castle of Leuktro, literally: “Mayna, Cisterna, and Belfonte in partibus Sclavonie” [47, p. 433].

-

5. The French version of “Chronicle of Morea”, circa 1340, refers to events in 1296. Then Michael Spani, the powerful lord of Kisterna and of other castles around it, joined the forces of the Frankish prince of the Principality of Achaia, Florent of Hainault, after his request for military backup. This version of Chronicle narrates (par. 823): “Spany, un puissant hommes des Esclavons, qui estoit sires de la Gisterne et des autres chastiaux entour” [39, p. 137; 66, p. 17].

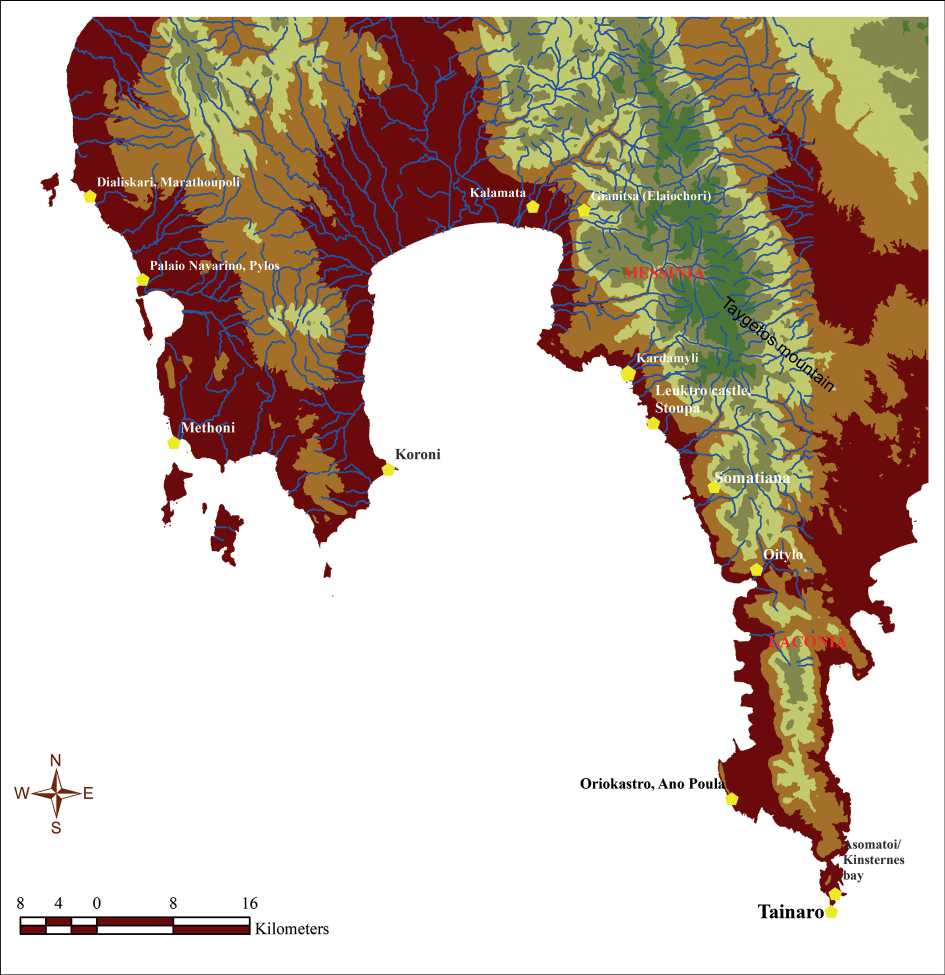

From the aforementioned scarce in number and sparing in detail references, it seems that Kisterna and Zygos were two vaguely separated areas (Fig. 7): Kisterna extended to the coast, where the castle, named Leuktro (Beaufort), was built by the Franks. It was adjacent to the uplands, the Zygos, where Slavs were settled (in general, see [33]). Both areas were under the Frankish Principality of Morea until 1262, when they were retrieved to the Byzantines. Moreover, it was the Slavs, the tribes of Melings and Ezerites, that in fact exercised control, sometimes circumstantially, over the region. Especially the Spanis family had undertaken an influential role as military chiefs and local governors, initiating socio-economic activities ranging from piracy to church and artistic sponsorship [3; 27; 28].

A comprehensive interpretation of the place names may sufficiently reveal the former viewpoint of van Leuven [68]. However, I am in favor of claiming what is clearly stated and matched by the material traces: Leuktro castle should be identified with the surviving same-name focal fortification in Stoupa, in NW (modern day Messinian/Outer) Mani. Then Kisterna was the adjacent area, from time to time, encircled or even ruled by the Slavs (Fig. 7). It is rather strange that the Slavs Melings advised William I Villehardouin to construct a castle so as to sabotage other rival Slavic tribes (see point 1). These could be the Ezerites or another leading family, for example, the Eleavoulkoi in Gianitsa (modern day Elaiochori), NE of Kalamata. However, most probably the reality might have been what the

Greek Chronicle of the Morea doesn’t tell us: that the prince made a strategic move to isolate the Slavs from the fertile flatland [29], the trade routes, and the ports of Kisterna. This highlights the importance of Kisterna, along with the intensity of the struggle over who was (or was not) going to lay hands on its “goods”.

The emphasized exaggeration regarding the abundance of goods in Kisterna (“πολλοίς... τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς”: a great number of goods, “βρύον” < producing abundantly and amply) [61, p. 222] draws the image of a thriving rural landscape. Although the territory around the castle of Leuktro, wherever it may be situated in Messina or Laconia, remains fruitful even today (Fig. 4–7), Mani was never renowned, especially for its cultivation capacities. A reason for that is the lack of hydraulic sources: extended karstic formations prevent the creation of aquifers; therefore, despite frequent rainfalls, water can’t accumulate, and springs are sparse. That is corroborated by the naming of the peninsula, presumably deriving from the Greek word “μανός” < barren land (an etymology, however, that can be challenged) 7. Other areas in Messinia and Laconia could arguably compete for prolific agro-pastoral production compared to Mani, so probably that wasn’t for which Kisterna was praised.

George Pachymeres probably did not stress only the quantity or variety of the goods with his comment but implied their distinct quality, their trade value and their significant contribution to the regional economy. He did not feel the need to explain more, possibly because the name of Kisterna itself indicated, though in a dissimulated manner, that it was not the fertile lands that provided for the goods but rather the management of natural resources that allowed for the prosperity. Pachymeres’s persistence in focusing on the coastal area around Leuktro, no matter where the castle might have been built by the Franks, points out that the production, processing or trade of these goods were favored by proximity to the shoreline.

Pachymeres’s account was widely followed by Nikephoros Gregoras in his Byzantine History, compiled between 1337 and 1358. In the instance where he cites the lands delivered to the Byzantines by the Franks to free their captured prince William I Villehardouin, among the three “best” (highly appreciated) territories handed over was the “Leuktra” (Neutr. Pl.): “τρεὶς τὰς βελτίους ...καὶ τὴν περὶ τὰ Λεύκτρα Μαΐνην, ἢ Ταιναρία πάλαι πὰρ᾿ Ἕλλησιν ἐκαλείτο”) [67, p. 102], as it is said in chapter IV (“Leuktra of Maini, which was called once Tainaria by the Greeks”). Some new information is added here, misleading, according to some scholars (see [30, p. 128]): the region as an entity is officially called Mani, but in the “old days by the Greeks‛” (i.e., the indigenous pagan population?), it was called Tainaria (Fem. S), alluding to the Tainaro cape at the southernmost promontory tip of southern Laconian/Inner Mani. Gregoras, contemporary to Pachymeres, ignores or hesitates to appoint Kisterna as a part of Mani/Tainaria, near Leuktro. Right or wrong, Gregoras’s statement influenced later authors to use the term Tainaro to refer to the entire Mani peninsula. But whatever the case, still, no light was shed on this area around Leuktro and why it was among the “best” ones.

Apart from Pachymeres and Gregoras, a third source that refers to the area is the “Maius” (extended and supplementary) version of George Sphrantzes “Chronicon”, compiled before 1585 by Makarios Melissenos. Although Melissenos’s intentions are doubted by the scholarship, yet he is considered to have added “important changes... additional information... masterful descriptions” to the original text, being self-appointed as a “literary figure” rather than a forger [55, pp. 9-10; 56, pp. 139-191]. Melissenos’s work has been published and reproduced by Bekker [19], Migne [18], Papadopoulos 8; in Grecu’s edition, the place names of Leuktro and Tainaro are slightly altered in spelling [57]:

-

a) The lands that the Franks exchanged for the liberation of William I Villehardouin in 1262–1263 include reference to the Leuktra (Neutr. Pl.) of Mani, that once was called “the Ketaria” by George Sphrantzes ( Chronikon . Book II, Chapter II), added in Latin as Cetaria: “τὸ Λεῦκτρα Μαΐνης, τὸ ὁποῖον Κεταρία πάλαι ἐκαλεῖτο”) [19, p. 131; 18, p. 744]. Similarly, the “Nektaria” (Fem. S. or Neutr. Pl.), as once called, is applied to the whole Zygos, reaching up ...Oitylo (“...χώρα Πελοποννήσου τὸ Λεῦκρα Μαΐνης, τὸ καὶ Νεκταρία πάλαι καλούμενον καὶ πάντα τὸν ἐκείνου ζυγὸν ἄχρι καὶ τῆς Πύλου τοῦ λεγομένου Οἰτύλου”) [57, p. 270.1–2].

-

b) There were territories that Theodore Palaiologos ceded to his brother, Constantine,

in 1428. Among them, the Leuktra (Neutr. Pl.) of Mani was once called by the Greeks Tainaria (Fem. S.) cape (see George Sphrantzes . Maius chronikon . Book I, Chapter I): “τὰ Λεῦκρα Μαΐνης, ἣ καὶ Ταιναρία πάλαι ἄκρα ἐκαλεῖτο παρ᾿ Ἕλλησι”) [19, p. 17; 18, p. 650] or “Netaria” (Neutr. Pl.) was once named by the Romans in the Peloponnese (“τὰ Λεῦκρα Μαΐνης, τὰ καὶ Νετάριά ποτε καλούμενα... Καὶ... οἱ Ρωμαῖοι ἐν τοῖς τῆς Πελοποννήσου χεῒρα ἐπέβαλον...”) [57, p. 162.27–28, etc.].

Evidently, these citations recall the established tradition of Gregoras 9, but there is confusion caused not only by Melissenos but also by his editors. This is regarding the wrong spelling of Tainaro, in particular the displacement of T and its replacement by N, the persistence of the -ε- instead of the correct -αι- and of the neutrum plural or feminine singular form (Nετάρια-Netaria) instead of the common neutrum singular (τὸ Ταίναρον-Tainaron). In the first instance (a), an awkward alternative spelling as “Ketaria” (or Nektaria), attested as Cetaria in Latin, is delivered, offering us a daring chance not to link it a priori to Tainaro. It might be possible that Melissenos (and his editors) confused the two places and subsequently two place names: Tainaro, which was well and widely known bearing the same unaltered name for centuries, and Ketaria, which referred specifically to the area around Leuktro, the once called Kisterna, from the end of the 13th century until the end of the 14th century. That name, Ketaria, according to Melissenos, was widely used “in the old days” by the indigenous “Greeks” (pagans?) as they are mentioned. This toponym was so strange, remote, and unheard to him that it provoked uncertainty, yet, it still somehow echoed Tainaro.

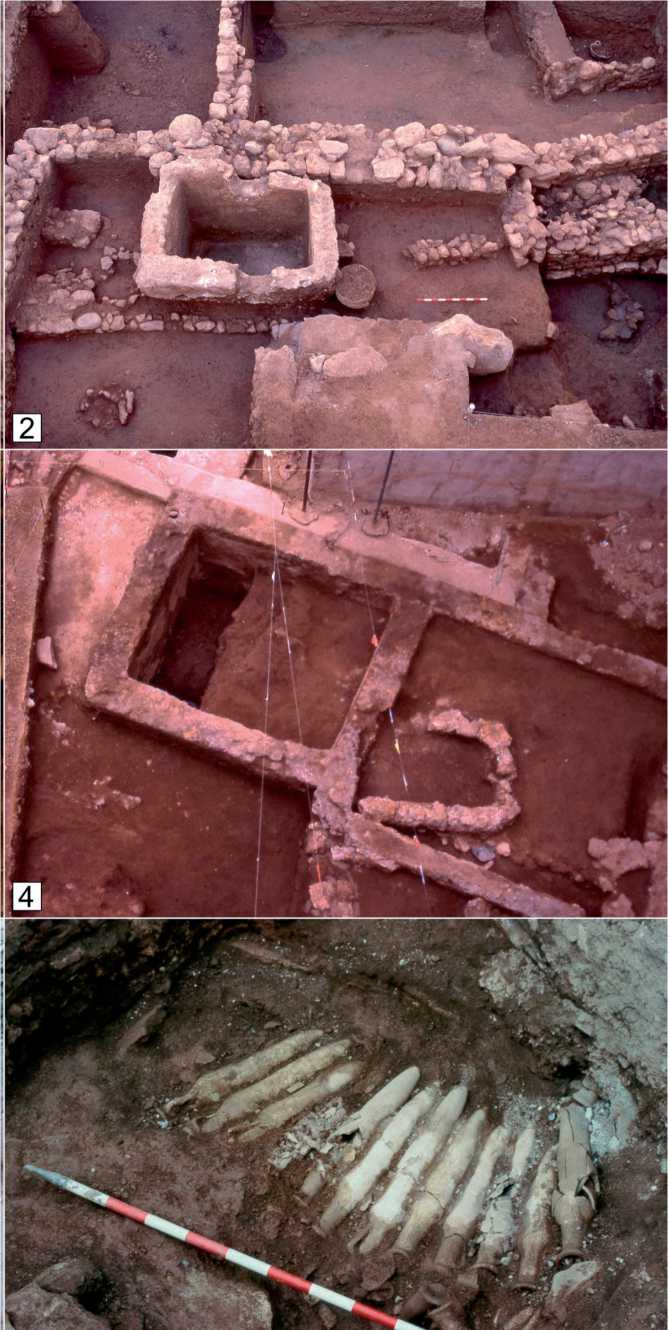

Before rejecting Ketaria as a misconception of Tainaro or even a ‘fabrication’ by Melissenos, it is worth tracing the meaning of the Latin word ‘Ketaria’. The term ‘cetaria, -ae’ is not very common, found in written sources dated from the 1st century BC until about the 8th century CE. It refers to complexes of built or rock-cut shallow basins, vats or tanks that were interconnected via channels, forming the infrastructure for processing (but not breeding) fish. It is demonstrated by some examples in other Mediterranean regions [5; 12; 20; 22; 45] (Fig. 8–10). These constructions occupied extensive areas and necessitated plenty of water for their operation; therefore, cetariae were usually installed in rocky coastal locations or, less often, alongside river banks or streams. Small settlements were developed around them to host the workforce involved – the high number of slaves, assistants, traders, and clients – but also to keep the smell and the discarded fish remains distant from residential zones [15; 1]. Cetariae produced the highly valued and much appreciated salted by-fish condiments, gaurum sauce, and fish paste. These commodities had not only culinary value but also trade advantages, as they were light and easy to transport and also preservable for a long time (see in general [13; 24; 41; 43; 48; 64; 65]. The processing of fresh fish involved several stages, as the flesh had to be gutted and cleaned, salted, dried, pickled, and ground under suitable environmental conditions. Forest or dense vegetation prevented evaporation, so ideal were barren, rocky hillsides exposed to long, intense sunlight.

The operation of cetariae depended additionally on the provision of raw materials such as clay for the manufacture of hundreds of amphorae to store the commodities and plaster to coat and insulate some of the basins. Huge quantities of salt, a valuable merchandise, were also indispensable to this industry and increased the cost of these products (see in general [13; 24; 41; 43; 48; 64; 65]). A similar landscape also fitted other industries, for example, the production of purple dye from molluscs [10] or, less probable, the process of flax into linen fibres and threads [6, pp. 128-131]. These activities were practiced in similar establishments and often operated in parallel with fish factories. Evidently, the impact of cetariae on provincial economies and trade markets was so significant that resulted in naming whole towns after them, especially in the western Mediterranean [43, p. 113].

It is now interesting to trace how Ketaria ended in Melissenos’s work and what this could possibly mean. Melissenos added new place names that did not exist in the original Sphrantzes’ “Chronicon” in several instances [11, pp. 17-18], due to his personal knowledge of the area or, more likely, copying from a Latin manuscript [55, p. 150]. If Ketaria truly existed as a place name, this could indicate the operation of cetariae on the coastline of NW (Messinia) or southern (Tainaro-Laconia) Mani, with Leuktro castle (in Stoupa or in Ano Poula) as the focal-supervising point. The industrial activity must have characterised the region to such a degree that it allegedly led to its unofficial appellation during the Roman and late Roman times (“Νετάριά ποτε καλούμενα”). By the time of the Frankish conquest in 1205, the Latin name would have already fallen out of use, but the memory, or possibly, the operation of the fish processing factories must have been still vivid. No wonder why the new rulers called their conquered land Kisterna, probably after the feature that was mostly distinguished in the regional landscape: the cisterns, basins, and tanks functioned as cetariae 10.

Still, another piece of the puzzle is missing: the name assigned to this area by the Byzantines. This would be a toponym that was widespread before the middle of the 13th century. This toponym is “Lakkoi” (“Λάκκοι”), found in the French, Greek, and Aragonese (1393) versions of the “Chronicle of Morea”. The place name in singular form (Lakkos – Λάκκος) was used to define a cluster of villages around Pamisos, the river artery that runs through the central Messinia plain (Fig. 1) [44, p. 67; 8, pp. 72-76]. Its tributaries shaped water-catching pits, supposedly attributing to the appellation “Lakkos”. However, at least in one instance, this toponym refers to another area, somewhere around NW Mani, when the twelve Frankish baronies were founded in 1205. Among them, there was a certain tenant-in-chief, Sir Luc, who was granted only four fiefs at the area “Lakkoi of Gritsenon/Gritsena” (La Gritte, Lacogrisco) (see in detail [68, pp. 45-52]).

The exact location of Lakkoi in NW Mani has not been identified with certainty. The fact that the baronies were associated with the existence of a castle adds further to the problem. A general idea is that the name has to do with the vertical cavities and natural formations (gorges, caves) that shape the regional landscape. However, it is also plausible that Lakkoi referred to depressions such as pits, basins, and tanks, meaning the extended cetariae complexes with the castle of Leuktro (in Stoupa or in Ano Poula) serving as the focal-supervising point. It has been advocated that the fortified sites assumed no particular defensive role [68, pp. 57, 65] but rather controlled access to passages, livestock transhumance, trade activities, and tax collection of the Slavs that were in need of the lowlands [29].

Lakkoi is further stressed as a place name by the troubling term “ton Gritsenon (Gritsena)”, “Grisco”, or “Gritte” that contributes to the characterization of the fief [37, pp. 308-312; 40, p. 101]. According to J. van Leuven [68, pp. 5152], Gritsena could be linked to Gournitsa village, in the north of Kardamyli, but no etymological interpretation has been attempted. The word may be of Slavic origin, either deriving from the word grič < hill, craggy terrain, or grez < marsh, wetland. It is also known as an Albanian family name, common in the wider area south of Leuktro, surviving until post medieval times (Fig. 11–12) [34, pp. 291-292]. Alternatively, it could be associated with the Greek word “γρύτη”, referenced in “Geoponics”, the famous treatise, to the process of fish catching (especially in rivers), garum preparation, and salting: (Geoponica, XX, 7, 1; XX, 12, 25) [17, pp. 517-518, 519-520; 59, p. 451].

Either way, Lakkoi sounds like a potential byzantine place name to have succeeded the Roman and late Roman Ketaria and to have coincided with the Frankish Kisterna, no matter where it was situated, in NW or southern Mani. Based on this hypothesis, the schematic representation of the place names through the ages should be reconstructed as Ketaria (R and LR) ⸻> Lakkoi (BYZ) ⸻> Kisterna (FRA) ⸻> unknown (OTTOMAN). The lacuna during the Ottoman rule (1460–1821) may be attributed to the overall decline in the strategic, political, and economic importance of the area, the oblivion of past names in parallel to the complete assimilation of the multi-ethnic inhabitants into a Hellenized culture, and the predominance of Mani appellation for the entirety of the peninsula [49].

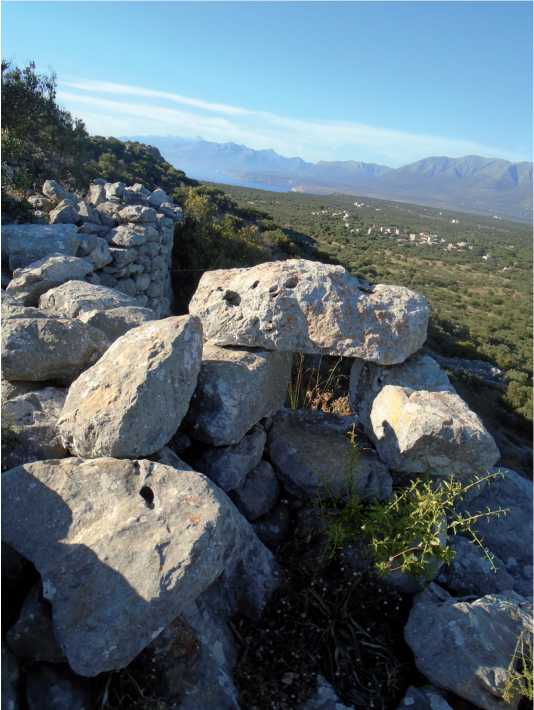

Revisiting b) the archaeological evidence. Archaeology does not provide much evidence to reinforce the proposed interpretations. Nothing is preserved around the castle of Leuktro, the suggested location of Kisterna in NW Mani, as modern-day Stoupa is densely built. Only salt pan formations, still standing out along the expanding rocky shoreline, indicate that the tremendously valuable commodity, essential for fish and purple dye processing, was centuries-long provided (Fig. 13) [60]. The castle of Leuktro itself, built on a coastal hilltop location, supervised the passages to and from Kalamata and Laconia and to the Taygetos uplands (Fig. 4, 7), and aimed rather to control the trade activities of the Slavs Melings than serve as a military outpost. Textual references and circumstantial finds confirm habitation at the hilltop and the slopes at least from Roman times, while probably a byzantine phase pre- existed before the construction of the castle by William I Villehardouin in circa 1250 [46, pp. 217, 219]. Today the castle lies heavily ruined, but still attention-grabbing is the Frankish cistern, among the earliest and finest samples of their hydraulic technology (Fig. 14–16). Measuring 4.35 m (length), 3.85 m (width), 3.50 m (depth up to preserved wall) / 4.60 m (depth up to vault formation), it was most probably fed by water guided off the roof of the (today dilapidated) tower at its south side [7, pp. 502-504; 9, pp. 152-153].

Some six kilometers north of Leuktro lies Kardamyli, and right in front of its harbor bay is a picturesque islet today called Meropi (original name unknown, previously recorded in Venetian maps as “La Madonna”). It was once fortified almost entirely, but for its southern side, segments of the walls from different periods are still preserved (Fig. 17). It has been claimed that it might have been the castle of Lello, one of the fiefs of the Lakkoi/Gritsenon barony handed over to Frankish families in 1205 [27, pp. 183-196; 28, pp. 226-239; 68, pp. 49-51]; however, this remains open to debate. A post medieval monastery was founded there in the 18th century, built with scattered ancient and early Byzantine building material (Fig. 18), whereas fragments of Roman or late Roman vessels are dispersed, especially on the western side of the islet. In addition to protecting the harbour, the islet could host the trade of goods that were produced aloing the shoreline. Interestingly, similar settings have been noticed in several cetariae [58].

Very few cetariae are known in the Peloponnese, even less in Messinia, usually being confused with fish breeding tanks. Such could be the rock-cut tank measuring 6.00 m in length and 3.00 m in width, with adjacent salt pans at the Dialiskari rocky coast at Marathos/ Marathoupoli, in western Messinia (Fig. 19– 20) [62]. The possible existence of adjacent plastered vats indicates that there might have been a small scale fish processing facility alongside fish breeding, as noticed in other areas of SW Messinia (Methoni, Koroni, Palaio Navarino in Pylos) (Fig. 21–22) [53]. Salt processing was also taking place in extended areas across the coastal southernmost part of Mani, in particular at Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro cape [60].

Tainaro has reached almost mythological extremes in collective psychology due to its association with the ancient Oracle of the Dead, the psychopompeion. However, a recent groundbreaking study deconstructed its ‘supernatural’ dimension [16], acknowledging the secular character of the archaeological remains at Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay, dated back to the Hellenistic period and after (Fig. 23). Among them, the salt pans and the numerous non-functionally identified cisterns and basins stand out: of various sizes and shapes, open or initially covered, some of them plastered, interconnected with stairs or channels, allude to a cetariae workshop (Fig. 24–26). Moreover, Greek and Latin authors share the information that “the sea of Lakedaimona was rich in the mollusc providing the purple dye” [70, p. 110]. Processing molluscs for purple dye and trading this precious commodity was an activity usually practised in the same establishments with fish byproducts. The favorable landscape and the suitable geomorphology of the coastal rocky location reinforce this interpretation: deprived of thick vegetation, coupled with the remoteness from a residential area. A ‘core’ settlement identified, including the famed temple of Poseidon, was purposed to host slaves and workers (Fig. 27).

Conclusions. If even a slice of this intellectual venture is correct, no matter Kisterna’s localisation in NW (surrounding Leuktro castle in Stoupa) or in southern (Oriokastro in Ano Poula promontory or in Tainaro) Mani, it might contribute to our understanding of its naming and which goods it represented. The hypothesis structured links evidence from written sources, material traces, and etymologies within intensified, centuries-long aquaculture activities that promoted regional sustainability, secured the population’s resilience, and advanced the micro-economy. The plausibility of a place name reflecting such an impact on shaping local histories and archaeologies cannot be ruled out, following a challenging interdisciplinary approach. This is deemed necessary, especially when it comes to decoding the past of one of the most obscure, but at the same time, intriguing edge of the Byzantine empire, such as the Mani peninsula.

NOTES

-

1 I thank very much Prof. Alejandro Quevedo for granting me the right to use the photo (Fig. 8)

and Konstantina Gerolymou for the photo and her consultations concerning the location of the tanks (Fig. 21, 22). Greek personal names were transliterated according to the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium [50; 51; 52]; otherwise, I have applied the spelling closest to the Greek. The words (place name and toponym) are used interchangeably. The scientific editor is Yu.Ya. Vin.

-

2 That was Dikaios Vayacacos, a member of the Academy of Athens, strongly opposed by scholar A. Koutsilieris. The debate was first encountered some 60 years ago ([35, p. 79]; also see [36; 70; 69]).

-

3 [23, pp. 359-360]; here relevant bibliography about geography and history of Mani is included; also see [34, pp. 13-36]; as to attribution of fig. 2, see [44, maps no. 11-20].

-

4 As to the expression “of or around”, the problem is created by the ambiguous notion of the preposition “περί” that can be read as “around” or “related to” the theme of Ki(n)sterna. About the place name itself, both writings, with or without the -n-, apply. I follow the spelling of the Greek “Chronicle of Morea”.

-

5 Stoupa, the modern name of the area around Leuktro castle, is of unknown origin. Either etymologically deriving from the Latin “stuppa” or the Greek “στυππεῖον”. It can be associated with the act of pounding, presumably while processing raw materials such as fish to condiments, molluscs to purple dye, flax to linen fibres and threads. The Leuktro/a name remains equally a riddle; there is a remote allusion to the ancient Greek verb λεύω < hitting with stones. In details, see [49]; here the relevant bibliography and past views on the subject-matter are presented, and the reader may consult it for the previous scholarship.

-

6 For discussion, see [49]; also see in general [25, pp. 212-215] with relevant bibliography on the subject as well as [26, pp. 53-74; 63].

-

7 Mani, the name of the peninsula, is first referenced in the 10th century. The origin of the name is uncertain, believed to derive from the word μανός < barren land. I also see as probable the origin from the Latin word manus, alluding to the elongated formation of the peninsula and recalling the later Venetian appellation of Brazzo. The argumentation, however, on this issue goes beyond the frame of this paper.

-

8 The publication of I.B. Papadopoulos [54] is not accessible to the author of this article.

-

9 It is worth mentioning that Dorotheos’s Chronicon, contemporaneous to Melissenos’s Chronicon, follows Pachymeres’s account, attributing the name of Kisterna as “τῆς γῆς στέρναν” (a surface? cistern) [14, p. 475].

-

10 Interestingly enough, Kisterna in the French “Chronicle of Morea” (see point 5) is written with G- (Gisterna), not with C- (Cisterna), whereas the word cistern is used to literally describe tanks storing drinkable water [68, pр. 49-61, par. 563, 564].

APPENDIX

Fig. 1. The intense contrast of the relief on the Mani peninsula depicted in reversed orientation from south to north (creation: Athanasios Dimou, Surveyor Engineering and Geoinformatics)

Scale in kilometers

Fig. 2. Features of geomorphology and geology in the Mani peninsula (creation: Lida Kitsaki, Senior Graphic Design Associate)

Fig. 3. Map of the Mani peninsula and units of Messinia and Laconia provinces, referencing the main place names of the text (creation: the author)

Fig. 4. View of the coastal plains and the shoreline from a semi-ruined loophole at the walls of Leuktro castle in Stoupa, NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 5. View to the north of Ano Poula promontory and the surrounding plains in southern (Laconian/Inner) Mani. A red sign spots the location of the presumed Oriokastro

Fig. 6. The loophole protecting the entrance to the promontory of Ano Poula visible to the north

Fig. 7. The landscape around the two possible localizations of Ki(n)sterna in Messinia or Laconia. View of Zygos, the uplands hillside of Taygetos mountain, the plains and the coastline

Fig. 8. Roman cetariae (with the amphorae found in situ), excavated in Águilas, a coastal town in south-eastern Spain

Fig. 9. The archaeological site of Roman fish salting workshop at Baelo Claudia (Southern Spain), Factory VI, Vat P-5

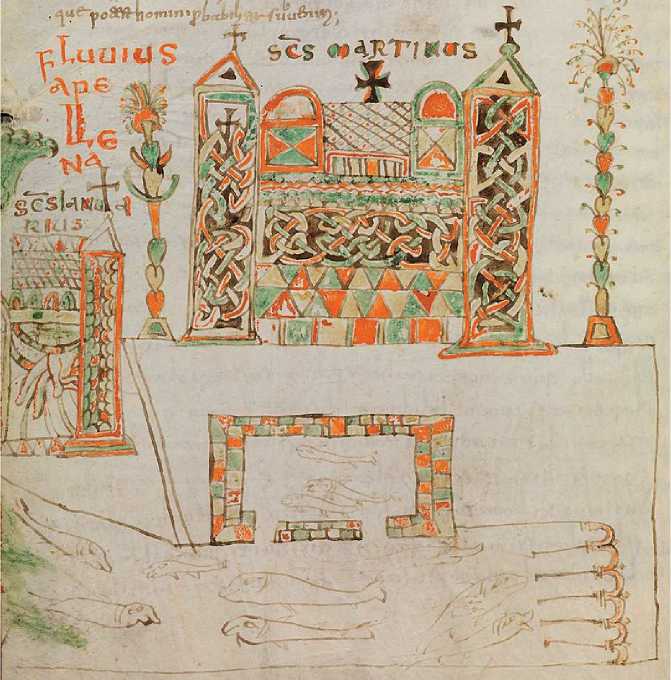

Fig. 10. A monastic fish breeding installation – a vivarium. The depiction of manuscript illumination, 8th century. Cassiodorus. Institutiones, Public Library of Bamberg, Ms. Patr. 61, fol. 29v

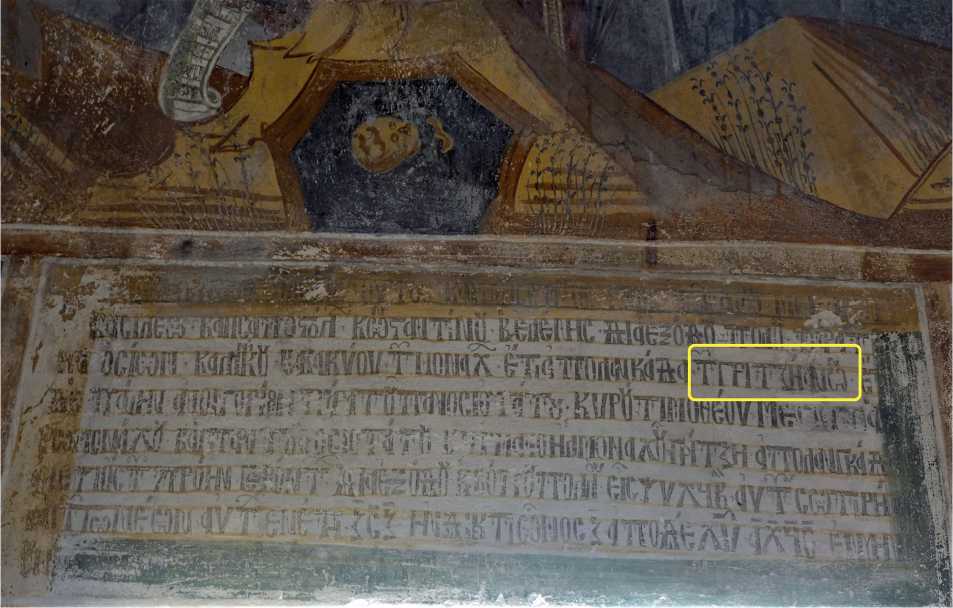

Fig. 11. An inscription of 1699 mentioning the family name of Gritsenon in the church of Saint Constantine in Somatiana village (ex Svina), Southern of Leuktro castle, in NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 12. The church of Saint Constantine in Somatiana village, and part of the Zygos landscape in NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 13. Salt pans across the rocky shoreline in Agios Nikolaos village, south of Stoupa, in NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 14. The Frankish cistern at the castle of Leuktro in Stoupa, NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 15. The spring of the collapsed barrel vault and the beam sockets’ traces of the Frankish cistern at the castle of Leuktro, in Stoupa

Fig. 16. Detail of the immured clay conduit at the cistern of Leuktro castle, channeling the water in the interior

Fig. 17. View of the northern fortification walls on the islet Meropi in Kardamyli, NW (Messinian/Outer) Mani

Fig. 18. The church and the monastery premises at ruins on the islet Meropi in Kardamyli

Fig. 19. Rock-cut channel and salt pans at Dialiskari, in Marathos/Marathoupoli, western Messinia

Fig. 20. The fish breeding (?) or cetaria tank at Dialiskari, in Marathos/Marathoupoli, western Messinia

Fig. 21. An open (initially unroofed) tank of unidentified function at Livadeia promontory in Koroni castle, SW Messinia

Fig. 22. A plastered basin, probably for salt or fish processing at Livadeia promontory in Koroni castle, SW Messinia

Fig. 23. View of the archaeological site opposite the Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro, (Laconian/Inner) Laconia

Fig. 24. The salt pans and salt processing structures at Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro

Fig. 25. An open rock-cut plastered tank near the Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro

Fig. 26. An open plastered circular rock-cut tank formation near the Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro

Fig. 27. Part of the landscape, tanks, channels and the famous mosaic at the temple of Poseidon near the Asomatoi/Kinsternes bay in Tainaro

Список литературы Revisiting the “Goods Of Kisterna” in Mani, southern Peloponnese. A complicated yet captivating storyline

- Amores F., Garcia E., Gonzales D., Lozano M.C. Una factoria altoimperial de salazones en Hispalis. Lagóstena L., Bernal D., Arévalo A., eds. Cetariae 2005: Salsas y Salazones de pescado en occidente durante la Antigüedad. Actas del Congreso Internacional (Cádiz, 7–9 Noviembre de 2005). Oxford, John and Erica Hedges Ltd., 2007, pp. 335-339.

- Arnakis G.G. George Pachymeres – A Byzantine Humanist. The Greek Orthodox Theological Review, 1966–1967, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 161-167.

- Αvraméa Α. Le Magne byzantine: problems d’histoire et de topographie. ΕΥΨΥΧΙΑ. Mélanges offerts à Hélène Ahrweiler. In 2 vols. Vol. 1. Paris, Éditions de la Sorbonne, 1998, pp. 49-62.

- Bartusis M.C. The Late Byzantine Army. Arms and Society, 1204–1453. Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Pr., 1992. XVIII, 438 p.

- Berdowski P. In Search of the Lexical Meaning of the Latin Terms cetarius and cetaria. Glotta, Zeitschrift für griechische und lateinische Sprache, 2013, Bd. 89, S. 47-61.

- Bon A. Le Péloponnèse byzantin jusqu’en 1204. Paris, Pr. univer. de France, I95I. XII, 231 p.

- Bon Α. La Morée franque. Recherches historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur la principauté d’Achaïe (1245–1430). Paris, Éd. De Boccard, 1969. Pt. 1, XVIII, 746 p.

- Breuillot M. Châteaux oubliés de la Messénie médiévale. Paris, L’Harmattan, 2005. 320 p.

- Breuillot M. L’ eau et les châteaux francs de Messénie (Péloponnèse, XIIIe–XVe s.). Gautier D., Mouillebouche H., eds. Actes du troisième colloque international du château de Bellecroix (Chagny). 18–20 octobre 2013. Chagny, Éd. du Centre de Castellologie de Bourgogne, 2014, pp. 148-161.

- Carannante A. Archaeomalacology and Purple-dye. State of the Art and New Prospects of Research. Cantillo Duarte J.-J., Bernal Casasola D., Ramos Muñoz J., eds. Moluscos y púrpura en contextos arqueológicos atlántico-mediterráneos. Nuevos datos y reflexiones en clave de proceso histórico. Actas de la III Reunión Científica de Arqueomalacología de la Península Ibérica (3.2012. Cádiz). Actas. Historia y Arte, No 10. Cádiz, Serv. de Publ. de la Univ. de Cádiz, 2014, pp. 273-282.

- Caroll M. Puzzling Names in the “Chronicon maius” of Macarius Melissenus: Pseudo-Phrantzes. Byzantion, 1974, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 17-22.

- Cassiodorus. Institutiones. Public Library of Bamberg, Ms. Patr. 61. URL: https://www.bavarikon.de/object/SBB-KHB-00000SBB00000157

- Curtis R.I. Garum and Salsamenta: Production and Commerce in Materia Medica. Leiden; New York, C.J. Brill, 1991. XV, 226 p.

- Dorotheos, metrop. Biblion istorikon periechon en sunopsei diaphorous kai eksochous istorias [A Historical Book Containing, in Summary, Various and Separate Stories]. Venice, para Nikolaō Glykei Publ., 1814. [1], 583 p.

- Edmondson J.C. Two Industries in Roman Lusitania. Mining and Garum Production. Oxford, BAR Publ., 1987. [2], 355 p., fig. 23.

- Gardner C.A.M. The “Oracle of the Dead” at Ancient Tainaron: Reconsidering the Literary and Archaeological Evidence. Hesperia, 2021, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 339-358.

- Beckh H., ed. Geoponica sive Cassiani Bassi scholastici de re rustica eclogae. Lipsiae, Teubner, 1895. XXXVIII, 641 p.

- Georgii Phrantzae Chronicon / Annales. Migne J.P., ed. Patrologiae cursus completus. Series graeca. In 161 Vols. Vol. 156. Parisiis, Apud J.‑P. Migne, 1866, cols. 637-1022.

- Bekker I., ed. Georgius Phrantzes, Ioannes Cananus, Ioannes Anagnostes. Bonnae, Imp. Ed. Weberi, 1838. III, 566 p.

- Fábricas de Salazón. Baelo-Claudia. Museos Arqueológicos de Bologna. Cádiz. Andalucía. Francis. WEB personal. URL: http://www.redjaen.es/francis/?m=c&o=80149&letra=&ord=&id=80156

- Failler A., Laurent V., eds. Georges Pachymérès. Relations historiques. In 3 Vols. Vol. 1. Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1984. XXXVI, 325 p.

- Garum Factory. Baelo-Claudia. Museos Arqueológicos de Bologna. Cádiz. Andalucía. Foto by C. Raddato. World History Encyclopedia. URL: https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13908/garum-factorybaelo-claudia

- Germanidou S. Mapping Agro-Pastoral Infrastructure in the Post-Medieval Landscape of Maniot Settlements: The Case-Study of Agios Nikon (ex. Poliana), Messenia. Journal of Greek Archaeology, 2018, vol. 3, pp. 359-404.

- Grainger S. The Story of Garum: Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World. London, New York, Routledge, 2021. XII, 301, [1] p.

- Haldon J.F. Byzantium in the Seventh Century. The Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge, Cambr. Univ. Pr., 1997. XXVIII, 492 p.

- Haldon J. The De Thematibus (‘On the Themes’) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Transl. with Introduct. Chapters and Notes. Liverpool, Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2021. XII, 283 p.

- Heslop M. Villehardouin’s Castle of Grand Magne (Megali Mani). A Re-assessment of the Evidence for its Location. Shotten-Hallel V.R., Weetch R., eds. Crusading and Archaeology. Some Archaeological Approaches to the Crusades. London, Routledge, 2021, pp. 183-244.

- Heslop M. Villehardouin’s Castle of Grand Magne (Megali Mani). A Re-Assessment of the Evidence for Its Location. Heslop M., ed. Medieval Greece. Encounters Between Latins, Greeks and Others in the Dodecanese and the Mani. London, Routledge, 2021, pp. 226-285.

- Huxley G. Transhumance on Taygetos in the Chronicle of Morea. Illinois Classical Studies, 1993, vol. 18, pp. 331-334.

- Kalonaros P. To Chronikon tou Moreōs. To ellēnikon keimenon kata ton Kōdika tēs Kopegchagēs meta symplērōseōn kai parallagōn ek tou Parisinou [The Chronicle of Morea. The Greek Text According to the Copenhagen Code After Additions and Variations from the Paris Code]. Athens, Ekd. Dēmētrakou Publ., 1974. 32, 400 p.

- Katsaphados P.S. Byzantines Epigraphikes Martyries stē Mesa Manē (13os–14οs ai.) [Byzantine Epigraphic Testimonies in Mesa Mani (13th – 14th C.)]. Athens, Idiōtikē ekd. Publ., 2015. 207 p.

- Κatsiardi-Hering Ο. Ktēmatographikoi chartes tou “Regno di Morea” ē autokratorikoi chartes. Eisagōgē [Land Maps of the “Regno di Morea” or Imperial Maps. Introduction]. Κatsiardi-Hering Ο., ed. Benetikoi chartes tēs Peloponnēsou telē 17ou – arches 18ou aiōna. Apo tē syllogē tou polemikou archeiou tēs Aystrias [Venetian Maps of the Peloponnese of the Late 17th – Early 18th Century. From the Collection of the Austrian War Archive]. Athens, Morphōtikoni Ethnikēs Trapezēs Publ., 2018. pp. 13-58.

- Koder J. On the Slavic Immigration in the Byzantine Balkans. Preiser-Kapeller J., Reinfandt L., Stouraitis Y., eds. Migration Histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone: Aspects of Mobility Between Africa, Asia and Europe, 300–1500 C.E., Leiden, Brill, 2020, pp. 81-100.

- Κomis Κ. Plēthysmos kai Oikismoi tēs Manēs 15os – 19os aiōnas [Population and Settlements of Mani in the 15th – 19th Centuries]. Iοannina, University of Ioannina, 2005. 701, [1] p.

- Koutsiliers A. Prosthēkai eis ta paratainaria topōnymia [Supplements to Paratainary Toponyms]. Platōn [Plato], 1966, vol. 18, pp. 57-102.

- Koutsiliers A. Paratainaria archaiopinē kai byzantina toponymia [Paratainary Ancient and Byzantine Toponyms]. Platōn [Plato], 1958, vol. 10, no. 1–2, σ. 240-249.

- Kriesis A. On the Castles of Zarnáta and Kelefá. Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 1963, Bd. 56, Hft. 2, S. 308-316.

- Lampakes S. Georgios Pachymeris. Protekdikos and Dikaiophylax. An Introductory Essay. Athens, National Hellenic Research Foundation. Institute for Byzantine Research, 2004. 259 p.

- Longnon J. Livre de la conqueste de la prince de l’Amorée. Chronique de Morée (1204–1305). Paris, Librarie Renouard, H. Lorens, 1911. CXX, 430 p.

- Longnon J. Les noms de lieu de la Grèce franque. Journal des Savantes, 1960, vol. 3, pp. 97-110.

- Lowe B. The Consumption of Salted Fish in the Roman Empire from Historical Case Studies. Buchet Chr., Arnaud P., De Souza P., eds. The Sea in History – The Ancient World / La Mer dans L’Histoire – L’Antiquité. Cambridge, Boydell & Brewer, Océanides, 2017, pp. 307-318.

- Lurier H. E., ed. Crusaders as conquerors. The Chronicle of Morea. New York, London, Columbia Univ. Pr., 1964. 346 p.

- Marzano A. Harvesting the Sea: The Exploitation of Marine Resources in the Roman Mediterranean. Oxford, Oxford Univ. Pr., 2013. XVI, [3], 365 p., 46 ill.

- Mc Donald A.W., Rapp Jr.R.G., eds. The Minnesota Messenia Expedition. Reconstructing a Bronze Age Regional Environment. Minneapolis, The University of Minnesota Press, 1972. XVIII, 338 p., 16 pl., 63 fig., 21 maps.

- Mirabelle. Archivio digitale della cultura medievale. URL: https://www.mirabileweb.it/manuscript/bamberg-staatsbibliothek-patr-61-(hj-iv-15)-manuscript/2401

- Molin K. Unknown Crusader Castles. Hambledon, London, Bloomsbury Publ., 2001. XXII, 421 p.

- Morgan G. The Venetian Claims Commission of 1278. Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 1976, Bd. 69, Hft. 2, S. 411-438.

- Mylona D. Fish-Eating in Greece from the Fifth Century B.C. to the Seventh Century A.D.: A Story of Impoverished Fishermen or Luxurious Fish Banquets? Oxford, Archaeopress, 2008. VIII, 171 p.

- Nikoloudis Ν. The ‘Theme of Kinsterna’. Dendrinos Ch., Harris J., Harvalia-Crook E., Herrin J., eds. Porphyrogenita: Essays on the History and Literature of Byzantium and the Latin East in Honour of Julian Chrysostomides. Aldershot, Hampshire, Burlington, Vermont, Ashgate, 2003, pp. 85-91.

- Kazhdan A.P. et al., eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. In 3 vols. Vol. 1. New York, Oxford, Oxford Univ. Pr., 1991. LIV, 728 p.

- Kazhdan A.P. et al., eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. In 3 vols. Vol. 2. New York, Oxford, Oxford Univ. Pr., 1991. XXXIII, pp. 727-1474.

- Kazhdan A.P. et al., eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. In 3 vols. Vol. 3. New York, Oxford, Oxford Univ. Pr., 1991, pp. XXXIII, 1474-2232.

- Panopoulou Α. Oi technikes tou alatiou stēn Peloponnēso ton 17o aiōna. Me aphormē dyo anekdota schedia tēs Methōnēs kai tēs Korōnēs [The Techniques of Salt in the Peloponnese in the 17th Century. On the Occasion of Two Anecdotal Plans of Methoni and Koroni]. To ellēniko alati. Ē Triēmero Ergasias (Mytilēnē, 6–8 Noemriou 1998) [Greek Salt. 8th Three- Day Work (Mytilini, 6–8 November 1998)]. Αthens, Politistiko Idryma Omilou Peiraiōs Publ., 2001, pp. 156-165.

- Papadopoulos I. B., ed. Phrantzes (Georgios). Chronicon. Bd. 1. Leipzig, Teubner, 1935. XXXIV, 201 S.

- Philippides M. The Fall of Byzantine Empire. A Chronicle by George Sphrantzes 1401–1477. Amherst, The Univ. of Massachusetts Pr., 1980. IX, 174 p.

- Philippides M., Hanak W.K. The Siege and the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Historiography, Topography, and Military Studies. Farnham, Surrey, Burlington, Vermont, Ashgate, 2011. XXIV, 759 p.

- Grecu V., ed. Pseudo-Phrantzes sive Macarie Melissenos. Chronica (1258–1481). Grecu V., ed. Georgios Sphrantzes. Memorii 1401–1477. În anexă. Bucuresti, Ed. Acad. RS România, 1966, pp. 149-590.

- Quevedo A., Sternberg M., De Dios Hernández García J. The Fish-Salting Production Centre of Águilas: Late-Roman Amphora Content Analysis. Bernal-Casasola D., Bonifay M., Pecci A., Leitch V., eds. Roman Amphora Contents: Reflecting on the Maritime Trade of Foodstuffs in Antiquity. In Honour of Miguel Beltrán Lloris, Proceedings of the Roman Amphora Contents International Interactive Conference (RACIIC, Cadiz 5–7 October 2015). Oxford, Archaeopress, 2021, pp. 409-418.

- Ragia E. The Circulation, Distribution and Consumption of Marine Products in Byzantium: Some Considerations. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 2018, vol. 13, no. 3, Special Issue. The Bountiful Sea: Fish Processing and Consumption in Mediterranean Antiquity. Proceedings of the International Conference, Held at Oxford, 6–8 September 2017, pp. 449-466.

- Saitas G.K., Ζarkia Κ.I. Topoi kai tropoi syllogēs alatiou stē Mesa kai stēn Eksō Manē [Places and Ways of Collecting Salt in Mesa and Exo Mani]. To ellēniko alati. Ē Triēmero Ergasias (Mytilēnē, 6–8 Noemriou 1998) [Greek Salt. 8th Three-Day Work (Mytilini, 6–8 November 1998)]. Αthens, Politistiko Idryma Omilou Peiraiōs Publ., 2001, pp. 254-294.

- Stamatakos I. Leksikon tēs archaias ellēnikēs glōssēs [Lexicon of the Ancient Greek Language]. Athens, Bibliopromētheutikē Publ., 1999. 1261 p.

- Stone D., Kampke A. Dialiskari: A Late Roman Villa on the Messenian Coast. Davis J.L., Bennet J., Alcock S.E., eds. Sandy Pylos: An Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino. Princeton, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2008, pp. 192-198.

- Karagiorgou O., Malatras Ch., Charalampakis P., eds. Taktikon. Studies on the Prosopography and Administration of the Byzantine Themata. Athens, Academy of Athens – Research Centre for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art, 2021. 904 p., 638, 241 ill., 6 maps.

- Theodorakopoulou T. To Salt or Not to Salt: A Review of Evidence for Processed Marine Products and Local Traditions in the Aegean Through Time. Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 2018, vol. 13, no. 3, Special Issue. The Bountiful Sea: Fish Processing and Consumption in Meditteranean Antiquity. Proceedings of the International Conference, Held at Oxford, 6–8 September 2017, pp. 389-406.

- Trakadas A. Fish-salting in the Northwest Maghreb in Antiquity: A Gazetteer of Sites and Resources. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2015. XII, 161 p., 129 Fig.

- Van Arsdall A., Moody. H., eds. The Old French Chronicle of Morea. An Account of Frankish Greece After the Fourth Crusade. Farnham, Surrey, Burlington, Vermont, Ashgate, 2015. XIII, 258 p.

- Van Dieten J.L., ed. Nikephoros Gregoras. Rhomäische Geschichte / Historia Rhomaïke. In 6 Teile. Εrster Teil (Kapitel I–VII). Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1973. VIII, 339 S.

- Van Leuven J. The Phantom Baronies of the Western Mani. Schryver J., Kennedy H. et al., eds. Studies in the Archaeology of the Medieval Mediterranean. Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 400–1500. Leiden, Brill, 2010, pp. 41-69.

- Vayacacos D.B. To Tainaron kai ta toutou onomata [Tainaron and His Names]. Eis mnēmēn K.I. Amantou, 1874–1960 [In Memory of K.I. Amantos, 1874–1960]. Athens, Menas Myrtides Ed., 1960, pp. 337-352.

- Vayacacos D.B. To Tainaron. Mythos kai istoria [Tainaron. Myth and History]. Papachristofillos M., ed. Peloponnēsiakē Prōtochronia. Istoria, laographia, technē, epistēma [Peloponnesian New Year. History, Folklore, Art, Epistema], 1960, t. 4, pp. 97-110.