Rocks in the religious beliefs and rites of the Ob Ugrians

Автор: Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 2 т.50, 2022 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This study, based on materials collected in the 18th–20th centuries, and on the author’s field findings over the last 40 years, shows the role of rocks in the Ob Ugrian worldview and ritual practices. Evidence is provided on the veneration of various natural stone objects. Reasons for the cult of worshipping such places are discussed. One reason was that the rock resembled a human or animal figure. In legends and myths, the stone houses of heroic ancestors were correlated with numerous caves in the Ural Mountains. The main part of the article introduces materials relating to the stone figures of deities and patron spirits, supported by mythical narratives explaining the ways that a mythological hero was changed into stone. Examples are given of the figures of deities with a stone base found among local groups of the Ob Ugrians, such as the Lyapin and Sosva Mansi, Synya and Polui Khanty. The role of rocks in childbirth and funerary rites is examined, as well as their role in economic practices such as fishing. In Khanty and Mansi mythological beliefs, the modifier «stony» was equivalent to «iron» or «strong».

Rocks, rites, legends, deities, Khanty, Mansi, legendary heroes

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145146778

IDR: 145146778 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2022.50.2.119-127

Текст научной статьи Rocks in the religious beliefs and rites of the Ob Ugrians

At the current time, there are few gaps in the studies of the worldview and religious/ritual practices of the Ob Ugrians. It is now possible to combine the evidence obtained at various times in various areas, and to create monographic works or specialized overviews on the basis of the findings.

The correlation between paraphernalia and mythology is relevant for the study of the traditional culture of the Khanty and Mansi, since cultic attributes constitute the most stable core of a ritual as a concentrated expression of religious and mythological beliefs. Cultic paraphernalia among these two small peoples can be divided into natural and man-made items; rocks play an important role among the former. Over the past three centuries, travelers and scholars have collected rich evidence on the use of rocks in the rituals of the Ob Ugrians and have recorded information about revering natural stone objects. Fairy tales, legends, and oral traditions contain brief references to rocks. However, there has not been a single overview of this topic and the present article is intended to fill that gap.

Natural stone objects

Revering natural objects of stone is typical of both the Khanty and Mansi. In the 18th century, there was information on the special attitude toward the “Ostyak prayer stone on the Shakva”, as well as on the “carved deer stone, or ‘elk calf’ stone, over the Sosva River, over which a special yurt was built, to which the Voguls came from distant lands to ask with sacrifices and small gifts for a fortunate hunt” (Bakhrushin, 1935: 26–27). In the first quarter of the 18th century, one could see the sacred stone of the Voguls inscribed with magical

signs near the Blagodatsky mine in the north of the Ural Mountains (Ibid.).

According to G.F. Miller, in the early 18th century, in the Yalpyng-ya River basin (the right tributary of the Northern Sosva River above the village of Lyulikara), there was a sacred stone (of ordinary shape), which was called an idol ( Lunkh or Pupyg ), as well as a sacred tree. These were venerated through the sacrifice of deer (Sibir XVIII veka…, 1996: 237).

The Mansi call a forested promontory about 70 m high over the right bank of the Northern Sosva River, 2 km above the village of Manya (Berezovsky District of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra), Akhtys-us ‘Stone town’. According to a legend about a cave near the cliff Vangrenyol, “a stone bridge used to be between Vangrenyol and Akhtys-us, connecting these two areas, on which skirmishes often took place between the warriors who lived in Akhtys-us and those who came from down the river” (Gondatti, 1888: 38). Most likely, this was the Iskar Old Settlement (Stone town) located, according to Miller (1740), on the right bank of the Northern Sosva River (Sibir XVIII veka…, 1996: 245).

A legend says that a stone island in the middle of the Northern Sosva River, opposite the confluence of the Yalbynyi River, emerged after a battle between Takht kotil torum ‘The old man of the middle Sosva River’ and the forest spirit menkv , which ended in the victory of the former. When passing by this place, people would throw money into the water; if during a storm the boat would get stuck on a stone spit, which was a reminder of the victory over the menkv , those on the boat would throw a cauldron and some food into the water to propitiate the spirit (Gondatti, 1888: 25). According to the legend, an afflicted woman turned into the stone that lies on the left bank of the Northern Sosva River near the village of Sartynya. She and her seven sons robbed travelers, but her sons were killed by mighty warriors sent against them by Takht kotil torum (Ibid.: 38). In another myth, Tovlyng paster fell through the ice during a hunt and turned into the stone that lay at the bottom of the Lyapin River near the village of Munkes. When the level of the water went down, the stone would become visible above the water (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 192). In the legend of the Pelym Voguls, the Son of the Ob Prince captured the owner of the underworld and put him in a sack; the sack hung on a larch tree for the winter and summer, after which the skeleton was shaken out into the water, and a rocky promontory emerged (Ibid.: 141).

According to the evidence collected by A. Kannisto in the early 20th century, two stones were known in the upper reaches of the Vizhai River near the Prayer stone, Yalpyng Ner ‘Sacred Urals’. The Voguls revered these stones—the “stone-man” and “stone-woman”—as patron spirits of the area; the former was called Khus-oyka ‘Servant-old man’ or Tagt-kotil-oyka-pyg ‘Son of the old man of the Middle Sosva River’. “Let the couple from the upper reaches of the sacred river bring good luck in fishing”, fishermen would say when catching fish in the Vizhai (Kannisto, Liimola, 1951: 280–281). There was a special prayer to these deities: “Two of stone who live in the high town of stone, two dressed in an ice coat, two dressed in an icy robe! The stone edge of your clothes, the stone hem of your clothes extends to the opening of the smoking pot which I placed! Oh, if only you would bring up fish with tails, fish with fins!” (Ibid.: 445–446).

A.A. Dunin-Gorkavich wrote that the Ostyaks revered stones that had distinctive sizes or shapes (having “at least the remote resemblance to the figure of a person or animal”). Pieces of cotton fabric, shawls, and money, as well as horse, sheep, or deer skins, were placed upon them. Among such sacred places, Dunin-Gorkavich mentioned the high hill “Bell Tower” at the Kul-egan River near Tyumkiny Yurty, Yegutskaya Mountain at the Yugan River, as well as Kamenny and Bartsev promontories in the vicinity of Surgut (1911: 36).

Even today, the Khanty revere many stone natural objects in the Synya River basin. For example, “a stone looking like a man lies not far from the village of Ovgort on the forest road. Old people say that once a man was killed there and turned into stone. They would put tobacco near it when they walked by” (Sokolova, 1971: 223). Another stone lying in the water near the bank of the Synya River above the village of Loragort is revered; it is called Vulkev iki ‘Stone big man or Stone old man’. According to the legend, a man was turned into this stone by a god (Taligina E.L., 2002: 71).

Stone houses of legendary heroes

According to the myths and legends of the Ob Ugrians, dwellings of deities and patron spirits are often houses made of stone: Akhvtas kol ‘stone house’, or Akhvtas-us ‘stone town’ (Balandin, 1939: 34). In the legend from the Konda River, the Lord raised the guardian spirits to the sky and hid them in a stone house (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 183). According to the beliefs of the Voguls, the third son of Numi-Torum named Ner-oyka lives on Elbyn-ner not far from the sources of the Northern Sosva River in a stone house with his wife and children (Gondatti, 1888: 20). In one of the legends, Ner-oyka lives in a stone chum (Istochniki…, 1987: 44).

In the legend “The Fiery Flood”, Torum ordered his wife to lock her newly born son in a “round stone house” (Mify, predaniya, skazki…, 1990: 70). The identification of dwellings of deities with stone houses is especially typical of the Ob-Ugrian groups living on the eastern slopes of the Urals. This can be explained by familiarity of the local population with the numerous caves located in this region.

Transformation of heroes into stone

Ethnographers have repeatedly recorded the tradition of revering deities represented by stones among the Ob Ugrians. There are many myths and legends that describe the origin of this phenomenon. “[Heroic] strong people, people brought down from the sky, were all the sons of Torum . Those who were strong, were turned into stone” (Munkácsi, 1896: 410). In a military song recorded by B. Munkácsi in 1889, one of the mighty warriors of the Trans-Urals, who was killed by a hero’s arrow, turned into a bare stone: “His scalp didn’t fall into my hands…” (Geroicheskiy epos…, 2010: 197).

According to a myth of the Sosva Voguls, “In the beginning, mighty warriors lived on the earth. They lived here for two thousand years. They fought with each other; the weak were defeated; some were turned into stone; the strongest survived as protective spirits” (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 82). The Voguls of the Konda River believed that the Lord of the Underworld would punish the bad deeds of those who would not take a stranger into their house or who would steal a bedding mat from another person—he would turn them into two grains of sand, or into two pebbles (Kannisto, Liimola, 1951: 125).

According to a legend, seven princes used to live near the village of Shaitanka on the Northern Sosva River. All of them died. An army of strangers came and killed their old mother and she was turned into stone; the mark of the sword was visible on the stone. When a person who was destined to live a long life put his hand on the stone, he felt that it was hot, but it would seem cold to a person who did not have much time left to live (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 156, 210, 257). A later version of the legend said that a large stone called Akhtas eka ‘Stone woman’, the patron spirit of the Mansi Animovs, lies on the bank near the village of Shaitanka. A mighty warrior once lived there on a high promontory. His wife betrayed him; he was killed, and the woman married the victor. Many years later, the relatives of the warrior attacked the woman; she wanted to slide down the cliff, but did not have time; she was caught with an iron lasso and turned into stone. In the past, the Mansi would stop at this stone and make a sacrifice (Bardina, 2009: 49).

In the fairy tale “The Crow with beads on its ears”, Matum-ekva turned two brothers into stone with the blow of a club; they came to life after drops of living water were sprinkled upon the stones (Mify, skazki, predaniya…, 2005: 95–101). In the fairy tale “Tirp-nyolp-ekva”, dogs attacked the older brothers, but they managed to turn into stone (Ibid.: 103–109). In the family legend of the Lyapin Mansi Albins, “When a Nenets shot at their father, he turned into a mountain, into stone” (Baulo, 2016a: 220). Ekva-pyrishch turned the king-khon into a stone, saying that “When people appear, the Mansi, the hunters should set up a cauldron to this stone, cook meat, grains, and then the hunters will make a good catch—with furs and fish” (Ibid.: 240).

Information on the stone figures of deities and patron-spirits

According to the information of N. Witsen, in the late 17th century, the Ostyaks in the vicinity of Surgut made idols from cloth and scarves, whose heads could be made of stone (Karjalainen, 1995: 53). In the early 18th century, G. Novitsky wrote that the Voguls in Chernye Yurty (near Pelym) “worshipped some spear to which a small stone of some kind was tied, which they considered to be a real idol revered from antiquity by their elders…” (1941: 80–81). In 1746, “a little stone idol was found” among the newly baptized Ostyaks from the Uvatskie Yurty, “to which they made sacrifices” (Ogryzko, 1941: 91). According to the evidence collected by I.G. Georgi, “along with humanlike stones, idols were ‘strangely formed stones’” (1776: 74). The same observation (idols of the Obdorsk Ostyaks were unprocessed stones) was made by M.A. Castrén in the mid 19th century (1860: 186) and by I.N. Glushkov in the late 19th century (1900: 69). The god Yalmal, revered by both the Samoyeds and Ostyaks, was represented in myths as a human figure carved out of stone and lying in a coffin; it was believed that he helped in sea hunting and fishing (Kushelevsky, 1868: 113).

Dunin-Gorkavich described several objects of religious worship from the collection of the Museum of the Tobolsk Governorate: an Ostyak stone idol whose base was a flat, elongated stone brought from the Lyapin River (28 cm long and 14 cm wide), “wrapped with scraps of woolen cloth in such a way that its end sticks out in the form of a head, and is covered with a hat of black and yellow woolen cloth; the outer clothing of the figure is a black woolen coat” (1911: 45); a roughly polished piece of granite in the form of a cross 21 cm long (Ibid.: 46); and two sacred stones—the first in the form of a child’s head and the second in the form of a frog’s head (Ibid.: 47). Previously, these stones had been located in the front corner of a yurt belonging to the Ostyak Asynkin (Asynkiny Yurty in Lokosovsky Volost of Surgut Okrug) along with the furs of fox, sable, and squirrel offered to them. The artifacts were given to the museum in 1889 by a certain N.A. Blinov from whom L.E. Lugovsky recorded the legend about their origin. The legend is tied with the unsuccessful matchmaking process of one mighty warrior. He cut off the head of a frog with a sword; the head “turned into stone, like the head of a holy creature”; trying to grab the child of a fleeing woman, the warrior tore off its head, and it also turned into stone because “the child was holy” (Lugovsky, 1894: 1, 3).

P.P. Infantiev saw a representation made of stone among the Voguls: “A small stone tile on which the likeness of a human face was extremely crudely carved… Two holes were supposed to represent two eyes; a third hole represented the mouth, and several lines were made for the eyebrows and nose” (1910: 161). On the watershed of the Yukonda and Morda Rivers, the Mansi revered a “stone woman” standing on an elevated, rocky place (Gorodkov, 1912: 199). U.T. Sirelius (late 19th century) described the Ostyak spirit-protector “Daughter of the earth god” as being in the form of a wooden anthropomorphic figure wearing clothes containing a small stone wrapped in a strip of fabric—the helper of the spirit (2001: 291).

Evidence from the early 20th century mentions a patron spirit of the Konda Voguls called “Prince resembling a red elk”, who lived in a cave on Denezhnyi Kamen (Money Stone); his figure was made of stone (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 167). In the village of Toshemka, there was also the representation of an elk made of natural stone, which was believed to help in hunting (Ibid.: 386). Kannisto wrote about the veneration of a “stone idol” as a spirit-protector. During the chase of the celestial elk, a stone was found, for which a sacred barn was built; a bloody sacrifice was made, and people began to venerate it (Ibid.: 136).

The figure of a deity, based on a Neolithic stone axe (17.0 × 8.5 cm in size) wearing clothes, was kept in the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism of the Soviet Academy of Sciences (now the State Museum of the History of Religion) in the collection of cultic objects belonging to the Khanty Dmitry Dunaev from Loktokurt (Grevens, 1960).

New evidence on the veneration of patron spirits with a stone base has been obtained in the course of field research in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug– Yugra and Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug over the last forty years. The patron spirit Akhvtas-oyka ‘Stone old man’ was known among the Lyapin Mansi in the village of Munkes in the mid 20th century. The base of the figure of Luski-oyki was a black stone with the figure of a man “with arms and legs” scratched on it (Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 26).

The figure of Akhvtas-oyka ‘Stone old man’ from the house of K. Pakin, who lived in the village of Verkhneye Nildino in the basin of the Northern Sosva River, was described as a piece of ore with high iron content. It was dressed in six shirts made of fabrics of various colors and wore a specially sewn hat made of young reindeer fur (unborn reindeer). Another stone of unusual shape, dressed in a specially sewn shirt, was in the chest next to the ore idol (Gemuev, 1990: 113–115). A female figure Torum-shchan was in a chest in the attic of the house of I. Endyrev in the village of Aneevo. The base of its head was a “stone from lightning and thunder” with a natural grid-like pattern. The stone was wrapped in three pieces of silk and fourteen small head scarves tied at the throat (Ibid.: 125).

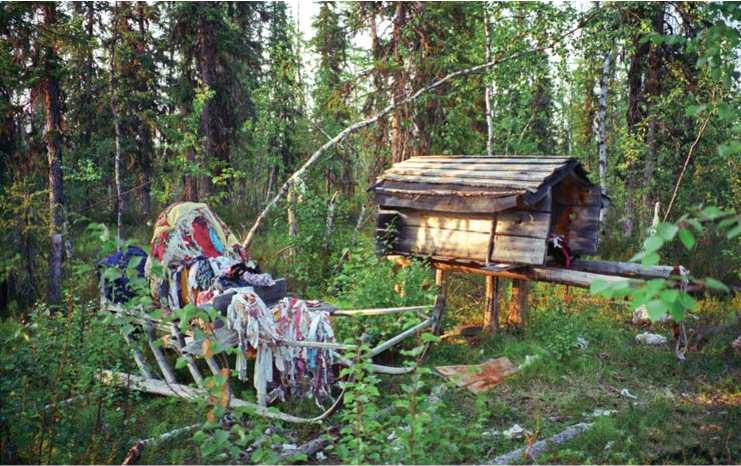

Among the Synya Khanty, the lord of the Synya River and patron of reindeer breeding was considered to be Khoran ur-iki ‘Reindeer Nenets old man’ (Synskiye khanty, 2005: 145), also known as Kev-ur-khu iki or Keiv ur khu akem iki ‘Stone Nenets old man’ (Perevalova, 2002: 45). His sacred place was located a few kilometers from the village of Vytvozhgort. The weight of the figure was 60–80 kg; it was with difficulty taken out of the sacred barn by four men (Fig. 1). Such a heavy weight suggests that the figure was made of stone most likely brought from the Ural Mountains; the choice of stone was determined by its belonging to an especially sacred place or the presence of a petroglyphic image on it (Baulo, 2016b: 56–57).

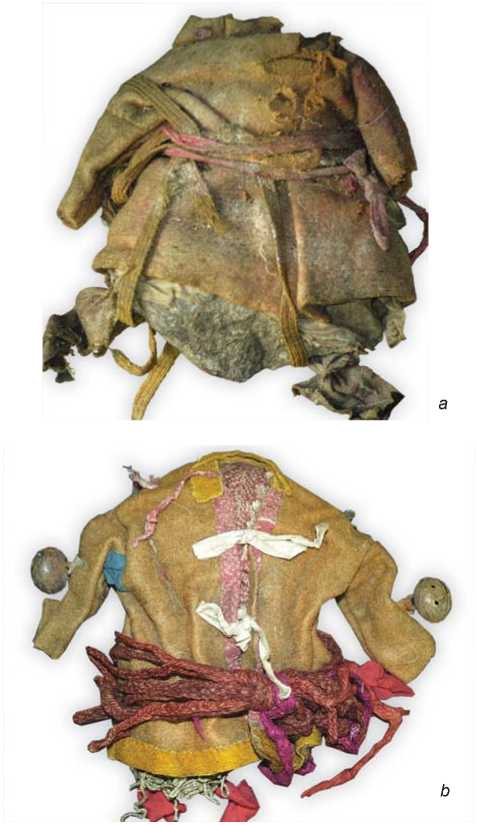

Figures of family patron spirits with the base being small pieces of unprocessed stone are quite common on the Synya River. In the village of Tiltim, a stone was dressed in a green shirt and deerskin overcoat, girded with red cord. The figure of the Kurtyamov family patron spirit is kept in an old house in the village of Yamgort. Its base was a flat round stone about 15 cm in diameter; the stone was dressed in a shirt and robe made of yellow woolen cloth, which was girded with red cord. The robe and stone were additionally bound with yellow trim (Fig. 2, a ). According to the description of the figure of a female deity from the village of Ovolyngort, its base was a stone of unusual shape (8.5 × 6.5 cm in size), wrapped in dark fabric and covered with a miniature head scarf with a fringe, which symbolized the gray hair of the goddess. On top, the figure was dressed in a robe made of thick, woolen fabric of yellow-brown color; large, round, copper bells were sewn on the sleeves, and false braids of twisted red woolen cord were sewn to the collar. The robe was tied with a belt of red woolen cord, to which a large copper ring and seven small copper rings were tied (Fig. 2, b ). A stone resembling an animal vertebra is kept in a sacred sled near the village of Muvgort.

In the Polui River basin (Priuralsky District of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug), in the village of Zeleny Yar, several stone idols from home sanctuaries of the Khanty have been described. The simplest type was a stone dressed in a broadcloth caftan or deerskin overcoat (the figures were 20–25 cm long) (Fig. 2, c ). A “family couple” included the male loong , represented by a stone with three brass plaques (Central Asian ornamentation) tied to it; the female loong was represented by a stone tied with a rope; it had round earrings of brass with glass inlays (Fig. 3).

Such figures of deities among the Polui Khanty are believed to “protect” reindeer breeding. One of the informants spoke about the circumstances of the

Fig. 1 . Figure of Khoran ur-iki (Reindeer Nenets old man) at a sacred place, 2000. Hereafter, photos by the author .

appearance of the stone loongs : “If a reindeer breeder experiences a decrease in deer, he goes to the shaman in the Polar Urals. There is a cave in Yemyn Kev ‘Sacred stone’. The man enters the cave, strips himself naked, and begins to listen carefully. The shaman tells him: ‘Get up and listen. If you hear the sound of a she-deer, you will be rich in deer; if you hear the sound of a he-deer, you will be poor.’ Our father also went there. He heard

Fig. 2 . Figures of patron spirits with a stone base. a – Yamgort, 2001; b – Ovolyngort, 2004; c – Zelenyi Yar, 2017.

3 cm

Fig. 3 . Spirit-stone. Zeleny Yar, 2002.

Fig. 4 . Stone idol. Sobtyegan River Basin, 2020.

the sound of a she-deer as if she was calling a fawn. And after that he had a lot of deer. People would take a stone from that place and keep it in their house as a patron spirit” (Ibid.: 146). S.V. Ivanov mentioned the syadai -patrons made of stones chipped from sacred cliffs by the Nenets (1970: 76).

A remarkable image of a Khanty family deity was kept in a sacred barn destroyed over time in the Sobtyegan River basin (Priuralsky district of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug). According to its photograph, its base was a stone head with human features; it was tightly bound with a piece of thick, yellow woolen cloth (such cloth is usually dated to the period from the first quarter to the mid 19th century) (Fig. 4).

There are references to the external features of mythical hero-ancestors in the folklore of the Ob Ugrians. Stone-eyed mighty warriors (“seven stone-eyed female por ”) is a common designation for the opponents of the heroes (Mify, predaniya, skazki…, 1990: 136, 513; Shteinits, 2009: 152–153). There was a belief that the endurance of a person depended on the size and strength of his heart. The heart of the younger brother of the “Mighty Warrior of Two Mountain Ridges” consisted of three stone eggs the size of a duck egg; therefore, that character could not be completely killed (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 18).

Amulets and offerings of stone

According to the Khanty, stones “could move from place to place and go towards individual fortunate people… The Ostyaks consider the owner of such a stone to be a fortunate and successful person in all kinds of fishing and hunting activities” (Startsev, 1928: 100).

The use of rocks by the Ostyaks as talismans (a stone was kept in the sacrificial chest together with other things) was observed by O. Finsch and A. Brehm (1882: 373). In the 1880s, K.D. Nosilov saw an old Vogul man on the Lyapin River, who kept his talismans in a small purse. They included stones made into the shape of animal heads. The Vogul Lobsinya gave the scholar a talisman as a gift, which was a pebble of dark green jasper made into the shape of small flatbread; a loon was depicted on one side of the talisman, and a beaver was represented on the other side. This talisman helped the Vogul man in hunting (Nosilov, 1997: 17).

In the early 20th century, S.I. Rudenko purchased a small stone with a natural hole inside—a so-called thunder stone—from the Voguls on the Sosva River. This stone was tied as an amulet to a shaman’s tambourine. Rudenko often observed crystals of rock crystal (quartz) wrapped in rags in sacred barns ((s.a.): Fol. 258, 277). The author of the current article also encountered similar crystals in complexes of the 19th century (Baulo, 2013: Fig. 223) (Fig. 5).

Among the cultic paraphernalia of the Mansi and Khanty, scholars have found archaeological tools, mainly arrowheads or adzes from the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age. A stone, tanged Neolithic arrowhead was kept in a sacred Mansi chest in the village of Khurumpaul (Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 158); an adze was discovered at the sanctuary in the basin of the Norkoln-urai oxbow (2014) at the sacred place of the thunder god Syakhyl-Torum . Such items were called Torum-sankv ‘God’s wedge’ or ‘God’s arrow’. It was believed that Syakhyl-Torum struck the evil spirits kuli and menkvs with these arrows (Gemuev, 1990: 139); the Emder mighty warriors from the epics were struck with thunder stone arrows from the sky (Patkanov, 1891: 17).

Fig. 5 . Pieces of rock crystal (quartz) as a part of cultic paraphernalia of the Lyapin Mansi. Yasunt, 2008

Rocks in rituals of the life cycle and economic practices

Rocks were used in rituals associated with the birth and death of a person. During the time when a child had no teeth, the Lyapin Mansi put nyor akhvtas (a transparent crystal stone) on the bottom of the cradle. It was believed that in this case the household spirit would not approach the baby (Baulo, 2016a: 53). A piece of rock crystal was also placed as a talisman on the bottom of the cradle among the Northern Khanty (Sokolova, 2009: 388); another kind of stone might also serve as such a talisman (Taligina N.M., 2004: 82).

On the Middle Konda River, when the deceased was brought out of the dwelling, a grindstone heated in a furnace was placed on the bed (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 49). Residents of Tremyugan placed a pebble or piece of flint into the mouth of a dead child to protect people from the dead; while the Vakhovo Ostyaks put a small stone on the heart of a stillborn child for the same purpose (Karjalainen, 1994: 96). Among the Northern Khanty, it was forbidden to put flint with the dead, since it was believed that the dead were afraid of stones. Among the Mansi, it was forbidden to put flint and grindstones into a coffin (Sokolova, 2009: 451–452). The legend “How man became mortal” says that in order to revive a dead person, one has to place a stone on his legs? (Mify, predaniya, skazki…, 1990: 75).

Stones were often endowed with special properties when they were used in everyday life. Drawings of a magical kind were scratched on stone sinkers for nets; this was expected to ensure good luck in fishing (Ivanov, 1954: 48). According to V.N. Chernetsov, the Mansi and

Fig. 6 . Stone drag-net sinker with representations of fish. Evrigort, 2002

Khanty tried to give a certain shape to drag-net stone sinkers. If the stone was intended to ensure successful fishing, an image of a caught fish was engraved on it and even a small sacrifice was made to it (Chernetsov, 1971: 85). Representations of fish and a water lock with twig traps installed in it for catching fish appear on the surface of a drag-net stone sinker from the museum of the village of Sosva in Berezovsky District of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra (Gemuev, 1990: 114), and two fish were scratched on a stone from the village of Evrigort (Fig. 6).

Conclusions

In the mythology and ritual practices of the Mansi and Khanty, rocks have played an important role since the moment of creation of man by God. In the legend of creation, Torum saw a stone, touched it with his hand, and heat came from the stone. There was another small stone next to it. Taking it, Torum struck the large stone which crumbled, and woman-fire came out of it. Then he began to hit the stones against each other, lit a fire, gathered the people together, and began to warm them by the fire (Mify, predaniya, skazki…, 1990: 63).

The living space of a person was filled with natural objects made of stone. It is also obvious that stones were included into the religious and ritual practices less often among the inhabitants of the taiga and swamplands as compared to the inhabitants of the areas near the Ural Mountains. The former revered stones because they were rare. In 1790, the author of a note about the “Samoyeds from the vicinity of Berezovo” wrote: “…when a stone is found in a place where there are no stones, people revere it as an idol, and make sacrifices…” (Opisaniye…, 1982: 70). According to Karjalainen, the possibility of revering such stones as spirits was mainly based on the fact that the silty and swampy soil of the Ob region is poor in stones, and therefore individual stones that ended up on the banks of rivers attracted attention. If a stone was thrown ashore by spring high water, it could be considered a mysterious object and perceived as a petrified spirit. A piece of coal that was brought by the ice could be perceived as the liver of a mythical mammoth living underground (Karjalainen, 1995: 34). It was the opposite among the population living in the Cis-Urals: as ornamental material, stone played an important role in manufacturing (marking) the figures of deities and patron spirits simply because it was everywhere. Most likely, numerous caves in the mountains of the Urals contributed to the emergence of ideas about the life of gods in stone houses.

As far as economic specialization of rocks is concerned, they are more often involved in rituals among those groups of the Ob Ugrians who are engaged in fishing and reindeer herding. Fishermen often catch stones of intricate shapes with their drag-nets or see such stones on the banks of rivers; reindeer herders, who are forced to take their herds to the Ural Mountains in the summer, interact with stones directly.

As a rule, reverence paid to natural objects is associated with discerning anthropomorphic or zoomorphic features in their shape (cf. “at least a remote resemblance to the figure of a person or animal” (Dunin-Gorkavich, 1911: 36); “there is the ‘Stone old woman’ cliff on the Konda River, in which, as they say, one can recognize the outline of the nose” (Karjalainen, 1995: 34)).

Concerning such a feature of gods as “being of stone”, one should probably consider it as including the meaning of being strong. It is no coincidence that we see the equivalence of the epithets “being of stone” and “being of iron”: on the Upper Lozva River, the menkv forest spirits were said to have iron or stone skins (Kannisto, Liimola, 1958: 156–157, 218); “the goddess Als-ekva puts on iron clothes, stone clothes, so nothing could be done to her; a bullet from the gun will not hit her; an arrow from the bow will not hit her” (Ibid.: 166); the Vasyugan spirit was called a “prince having the form of a stone, having the form of iron, possessing an image” (Karjalainen, 1995: 34).

Thus, the combination of sources of different types— historical, ethnographic, and folk—has made it possible to create a specialized study on their basis, which reveals general and specific features in the attitude of the Khanty and Mansi toward natural objects made of stone, and describes the use of stone paraphernalia in religious and ritual practices of the 18th to early 21st century.

Список литературы Rocks in the religious beliefs and rites of the Ob Ugrians

- Bakhrushin S.V. 1935 Ostyatskiye i vogulskiye knyazhestva v XVI-XVII vv. Leningrad: Izd. Inst. narodov Severa.

- Balandin A.N. 1939 Yazyk mansiyskoy skazki. Leningrad: Glavsevmorput.

- Bardina R.K. 2009 Obskiye i nizhnesosvinskiye mansi: Etnosotsialnaya istoriya v kontse XVIII - nachale XXI veka. Novosibirsk: Izd. SO RAN.

- Baulo A.V. 2013 Svyashchenniye mesta i atributy severnykh mansi v nachale XXI veka: Etnografi cheskiy albom. Khanty-Mansiysk, Yekaterinburg: Basko.

- Baulo A.V. 2016a Ekspeditsii Izmaila Gemueva k mansi: Etnokulturniye issledovaniya v Nizhnem Priobye. Vol. 1: 1983-1985 gody. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Baulo A.V. 2016b Svyashchenniye mesta i atributy severnykh khantov v nachale XXI veka: Etnografi cheskiy albom. Khanty-Mansiysk: Tender.

- Chernetsov V.N. 1971 Naskalniye izobrazheniya Urala, pt. 2. Moscow: Nauka. (SAI; В 4-12).

- Dunin-Gorkavich A.A. 1911 Tobolskiy Sever, vol. 3. Tobolsk: [Gub. tip.].

- Finsch O., Brehm A. 1882 Puteshestviye v Zapadnuyu Sibir. Moscow.

- Gemuev I.N. 1990 Mirovozzreniye mansi: Dom i Kosmos. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Gemuev I.N., Sagalaev A.M. 1986 Religiya naroda mansi. Kultoviye mesta XIX - nachala XX v. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Georgi J.G. 1776 Opisaniye vsekh v Rossiyskom gosudarstve obitayushchikh narodov, pt. 1. St. Petersburg.

- Geroicheskiy epos mansi (vogulov): Pesni svyatykh pokroviteley. 2010 E.I. Rombandeeva, T.D. Slinkina (comp.). Khanty- Mansiysk: Print-klass.

- Glushkov I.N. 1900 Cherdynskiye voguly. Etnograficheskoye obozreniye, vol. 15 (2): 15-78.

- Gondatti N.L. 1888 Sledy yazycheskikh verovaniy u inorodtsev Severo-Zapadnoy Sibiri. Moscow: [Tip. Potapova].

- Gorodkov B. 1912 Reka Konda. Moscow: [s.n.]. (Zemlevedeniye; vol. 19, bk. 3/4).

- Grevens N.N. 1960 Kultoviye predmety khantov. In Yezhegodnik Muzeya istorii religii i ateizma AN SSSR, iss. 4. Moscow, Leningrad: AN SSSR, pp. 427-438.

- Infantiev P.P. 1910 Puteshestviye v stranu vogulov. St. Petersburg: [Izd. N.V. Elmanova].

- Istochniki po etnografii Zapadnoy Sibiri. 1987 N.V. Lukina, O.M. Ryndina (publ.). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Ivanov S.V. 1954 Materialy po izobrazitelnomu iskusstvu narodov Sibiri XIX - nachala XX v. Moscow, Leningrad: Nauka. (TIE, nov. ser.; vol. 22).

- Ivanov S.V. 1970 Skulptura narodov Severa Sibiri XIX - pervoy poloviny XX v. Leningrad: Nauka.

- Kannisto A., Liimola M. 1951 Wogulische Volksdichtung. Bd. 1: Texte mythischen Inhalts. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

- Kannisto A., Liimola M. 1958 Materialien zur Mythologie der Wogulen. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. (MSFOu; vol. 113).

- Karjalainen K.F. 1994, 1995 Religiya yugorskikh narodov. N.V. Lukina (trans.). In 2 vols. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Castrén M.A. 1860 Puteshestviye po Laplandii, Severnoy Rossii i Sibiri (1838-1844, 1845-1849). In Magazin zemlevedeniya i puteshestviy, vol. VI (II). Moscow.

- Kushelevsky Y.I. 1868 Severniy polyus i zemlya Yamal. St. Petersburg: [Tip. MVD].

- Lugovsky L.E. 1894 Legenda, svyazannaya s dvumya ostyatskimi idolami iz kollektsii “prinadlezhnostey shamanskogo kulta” v Tobolskom gubernskom muzeye. Yezhegodnik Tobolskogo gubernskogo muzeya, iss. 2: 1-3.

- Mify, predaniya, skazki khantov i mansi. 1990 N.V. Lukina (trans. from Khanty, Mansy, German, comp., intro., and notes). Moscow: Nauka.

- Mify, skazki, predaniya mansi (vogulov). 2005 E.I. Rombandeeva (comp.). Novosibirsk: Nauka. (Pamyatniki folklora narodov Sibiri i Dalnego Vostoka; vol. 26).

- Munkácsi B. 1896 Vogul népköltési gyüjtemény, vol. IV. Budapest.

- Nosilov K.D. 1997 U vogulov: Ocherki i nabroski. Tyumen: SoftDizain.

- Novitsky G. 1941 Kratkoye opisaniye o narode ostyatskom. Novosibirsk: Novosibgiz.

- Ogryzko I.I. 1941 Khristianizatsiya narodov Tobolskogo Severa v XVIII v. Leningrad: Izd. Leningr. Gos. Ped. Inst.

- Opisaniye Tobolskogo namestnichestva. 1982 Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Patkanov S.K. 1891 Tip ostyatskogo bogatyrya po ostyatskim bylinam i geroicheskim skazaniyam. St. Petersburg.

- Perevalova E.V. 2002 Voiny i migratsii severnykh khantov (po materialam folklora). Uralskiy istoricheskiy vestnik, No. 8: 36-58.

- Rudenko S.I. (s.a.) Ugry i nentsy Nizhnego Priobya. Arkhiv RAN (SPb.). F. 1004, Inv. 1, item 66.

- Shteinits V. 2009 Totemizm u ostyakov v Sibiri, iss. 3. N.V. Lukina (trans. from German). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Ped. Univ., pp. 151-164. (Arkheologiya i etnografi ya Priobya: Materialy i issledovaniya).

- Sibir XVIII veka v putevykh opisaniyakh G.F. Millera. 1996 Novosibirsk: Sibirskiy Khronograf. (Istoriya Sibiri. Pervoistochniki; iss. VI).

- Sirelius U.T. 2001 Puteshestviye k khantam. N.V. Lukina (trans. from German, publ.). Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.

- Sokolova Z.P. 1971 Perezhitki religioznykh verovaniy u obskikh ugrov. In Religiozniye predstavleniya i obryady narodov Sibiri v XIX - nachale XX veka. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 211-238. (Sbornik MAE; vol. 27).

- Sokolova Z.P. 2009 Khanty i mansi: Vzglyad iz XXI v. Moscow: Nauka.

- Startsev G. 1928 Ostyaki. Leningrad: Priboy.

- Synskiye khanty. 2005 G.A. Aksyanova, A.V. Baulo, E.V. Perevalova, E. Ruttkai, Z.P. Sokolova, G.E. Soldatova, N.M. Taligina, E.I. Tylikova, N.V. Fedorova. Novosibirsk: Izd. IAET SO RAN.

- Taligina E.L. 2002 Toponimy Synskogo kraya. In Narody Severo-Zapadnoy Sibiri, iss. 10. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ., pp. 70-77.

- Taligina N.M. 2004 Obryady zhiznennogo tsikla u synskikh khantov. Tomsk: Izd. Tom. Gos. Univ.