Russian specifics of dacha suburbanization process: case study of the Moscow region

Автор: Rusanov Aleksandr Valerevich

Журнал: Economic and Social Changes: Facts, Trends, Forecast @volnc-esc-en

Рубрика: Young researchers

Статья в выпуске: 6 (42) т.8, 2015 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Topical issues related to the planning of urban agglomerations development include registration and analysis of changes in suburban areas in the process of socio-economic development. It is manifest, among other things, in urbanization, which in relation to larger cities is replaced by suburbanization. Suburbanization process has been developing to the greatest extent in North America and Western Europe. Scientific research confirms that the majority of large urban agglomerations are in the stage of suburbanization. The pace of suburbanization in the world is different - the authorities of individual countries, regions or cities often take measures to limit or simplify it: they reconstruct central cities, set limits to the construction in peripheral areas, etc. In Russia, the process of suburbanization started to develop rapidly only after the socio-economic transformation of the 1990s that led to the emergence of the free market of housing and land. The aim of the present work is to determine the specifics of suburbanization in Russia on the example of the Moscow Region...

Suburbanization, dachas, dacha housing, second home, institutional factors, socio-environmental factors, population geography, moscow oblast

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147223785

IDR: 147223785 | УДК: 635.1 | DOI: 10.15838/esc/2015.6.42.15

Текст научной статьи Russian specifics of dacha suburbanization process: case study of the Moscow region

Dacha settlements are part of modern Russian agglomerations; they surround almost every major city and form new relationships with the suburbs. A.G. Makhrova, A.I. Treivish, and T. Nefedova and others are among Russian scientists who study this issue from a systemwide perspective; the approach of Russian researchers is somewhat different from those in other countries who consider country houses in the context of recreational tourism or real estate analysis [8]. An important part of the study of suburban areas is the definition of the nature of suburbanization, i.e. advanced growth of suburbs compared to the center.

The suburb as a place of residence outside the city that is characterized by low housing density has existed since ancient times; today, however, the vagueness of city boundaries complicates the definition of the term “suburb” itself that has long had a negative connotation. It was only in the middle of the 1820s that the former American slums began to transform into a decent place of living, from which the residents commuted to their work in the city [12]; and today the suburb in the USA is an urbanized area outside the central city (suburb) with the division of the suburbs into groups (“automotive”, “planned”, “California-type”, “external”, “white”, “black”, etc.) [16]. A similar use of suburban areas is an option of classical suburbanization, i.e. moving to the suburbs for permanent residence.

Empirical data show that suburban settlements not only exist in the world, but are also characterized by more or less similar development processes. In France summer residences once surrounded Paris, and now they are moving far off – to the coast and in the mountains. In the UK, many owners of urban buildings have rural houses too [2]. In Sweden, the first garden plots appeared in the late 19th century when rural residents were moving to cities in search of work. In 1906, the authorities of Stockholm allocated land plots for the first time – their area was up to 0.01 ha; those plots formed small settlements-colonies. After World War II, the country solved its food problem with the help of those land plots; in the 1970s, the size of the plots increased up to 0.07 ha, because their economic function lost its importance and the recreational function came to the fore [15]. In Finland, there are kesamokki (summer cottages) – small houses that are often located on the bank of some water body and that have a jetty with a boat; these houses are used for summer living and recreation; and puutarhamokki – small land plots used for gardening and vegetable and fruit farming, they have a small cabin, several vegetable beds and fruit and berry bushes, these plots are located on the outskirts of cities and are used for cultivation of berries, vegetables and fruits [14]. In Germany, tiny land plots up to 0.02 ha with small garden sheds appeared in the late 19th century and were called Schrebergarten after Moritz Schreber who advocated healthy lifestyle and love of nature; today they are also called Kleingarten, which means a small garden, Familiengarten – a family garden, Heimgarten – a home garden, Grundstuek – a land plot. Here one can grow flowers, vegetables, berry bushes, fruit trees and put a ready-assembled shed (it is prohibited to build it on one’s own), it is prohibited to live in it; it is also not allowed to erect other constructions on this land plot[13]. A kind of Polish analogue of the Russian dacha is dzialka rekreacyjna, which appeared in the period of the Polish People’s Republic and performed functions similar to Soviet dachas, and today it is an independent subject of out-of-town property [16].

However, scientific community regards dacha as a specific Russian phenomenon, as “a special form of spatial organization of human activity and, at the same time, part of urban, suburban or rural landscape” [3]; dacha, as a socio-cultural institution, has a long history reflecting the process of urbanization in Russia.

The aim of the paper is to identify the specifics of suburban resettlement as a special manifestation of suburbanization in Russia on the example of the Moscow region. In accordance with the aim the following objectives are set out:

-

1. To consider specific features and characteristics of suburban resettlement as a specific Russian manifestation of suburbanization.

-

2. To identify main groups of factors influencing the specifics of dacha-related suburbanization in the Moscow region.

-

3. Using key areas as example, to determine, how the main groups of factors determine dacha-related suburbanization.

The specifics of Russian suburbanization lies in the seasonal nature of suburban housing, which is located primarily in the dacha settlements of various types, which allows us to speak about specific dacha-related suburbanization [6].

Dacha suburbanization dynamics depends on the factors that can be divided into several groups:

-

1) institutional – related to the state policy of regulating population distribution across the country and supporting certain categories of population;

-

2) socio-environmental – related to environmental conditions of suburban areas, demographic situation, social stratification and mobility of population;

-

3) economic-technological – associated with reduction in production costs primarily due to the lower cost of land in the suburbs depending on rental relations, the implementation of scientific and technological achievements and development of transport, which helps create urban infrastructure in the suburbs.

The history of suburbanization in Russia has its specific features. First, the excessive concentration of population in major cities was combined with a sparse network of peripheral towns, which contributed to continuous migration from the village and seasonal migration [4]. Suburbanization in the conditions of Russia’s vast territories resulted in the emergence of phenomenon such as second seasonal housing of urban residents [5]. Moreover, traditional economic, geographic, demographic, and technological factors promoting suburbanization in Russia depended strictly on institutional factors, i.e. government’s permission or prohibition to use lands for dacha settlements. Back in the 17th century, the word “dacha” denoted a land and forest plot allocated by the government, i.e. a plot which is “gratuitous”; this immediately gave the notion of dacha a shade of oneness, which existing to some extent even now [8]. This predetermined potential legal ambiguity of dacha settlements that has been preserved throughout the entire “dacha history” of Russia: for example, in the Soviet period, it was allowed to impose formal restrictions on the type and size of dacha constructions; dachas could even be taken away from their owners if they did not cultivated their plots in time. Today, dacha functions are being virtually transferred to the settlements that formally retain their rural status, which greatly complicates the accounting of their residents.

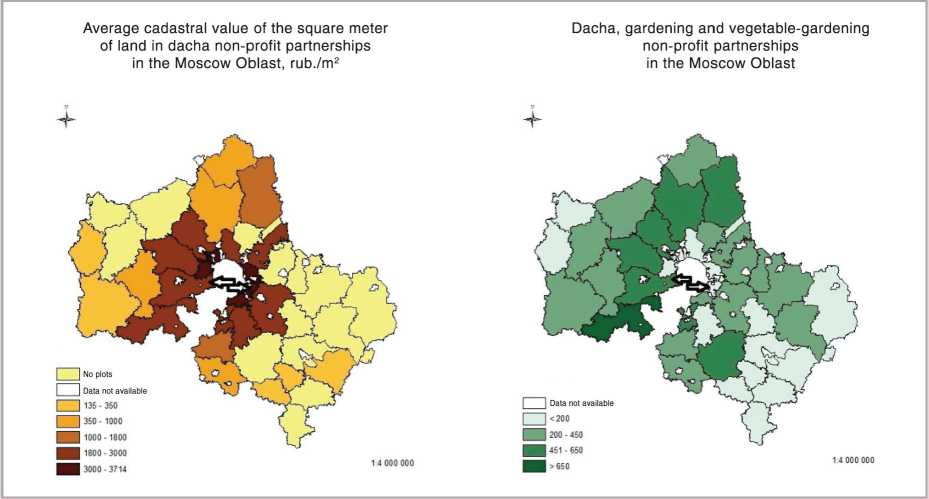

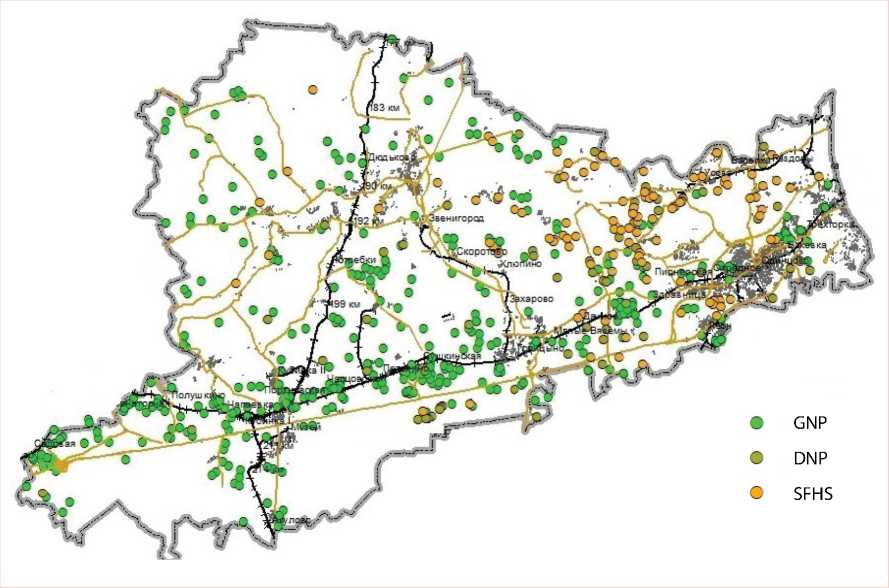

Like classic suburbanization, dacha-related suburbanization is heterogeneous – the dominance of different factors leads to different types of “dacha areas”, i.e. territories that can perform functions of dachas [1, 11]. As a result, the specifics of dacha-related suburbanization, for example, in the Moscow region, is different even in areas with similar economic and geographical characteristics such as proximity to city boundaries, infrastructure, population, etc. (fig. 1); this is illustrated by example of those regions of the Moscow Oblast that border on the capital city: Lyuberetsky District in the south-east and Odintsovsky District in the west (table).

The history of dachas in the Moscow region allows us to conclude that the period from the emergence of “dacha areas” up to the development in these areas of single family house settlements (SFHS) – the highest hierarchical type of suburban settlements – can be considered as a “full development cycle” of suburban resettlement [7]. The dacha area that was established spontaneously or was founded on the land especially allocated from the surrounding suburban area gradually develops either into dacha settlements or into a town, with different factors prevailing in either case. The inclusion of dacha areas in the city limits means complete degradation of dacha

Figure 1. Number of dacha settlements in the districts of the Moscow Oblast and the cadastral value of their land

Source: compiled by the author according to the information portal “Northern dachnik” for 2014 .

Comparative characteristics of Lyuberetsky and Odintsovsky districts of the Moscow region (as of January 01, 2015)

Indicators Lyuberetsky District Odintsovsky District Year of founding 1929 1965 Area, km2 122.31 1,289 Resident population, people 291,510 321,673 Population density, people/km2 2383.37 249.55 Share of urban population, % 98 66.8 Number of urban settlements 5 7 Average cadastral value of 1 m2 of land in suburban settlements of all types, rubles 2,809.,41 1,815.13 Number of dacha settlements of all types 45 544 Sources: compiled by the author based on the data of the official portal of the Lyuberetsky District ; official website of Odintsovsky District ; Internet-portal “Northern dachnik” ; Federal State Statistics Service (http://www. .

resettlement, but it becomes possible only under the absolute influence of institutional factors, i.e. administrative and territorial transformations of the city. This process is adjustable – during the entire history of dachas in the Moscow region, the city of Moscow absorbed its surrounding dacha neighborhood about 20 times and always in accordance with the specially issued decrees [17]. Thus, it can be assumed that the institutional factors are determined at the macroeconomic (national) level and have the same effect on dacha resettlement in all the surrounding suburbs.

Socio-environmental and economic-technological factors depend much more on microeconomic (district) components and local opportunities. They influence the formation of dacha settlements, which can change their functions, sometimes even preserving their type: for example, the settlement will have the formal status of a village, or a gardening non-profit partnership (GNP), but actually be a dacha non-profit partnership (DNP) or a SFHS in which people live year-round (used for permanent residence).

Among the main socio-environmental factors in the development of dacha settlements are natural recreational resources of the Moscow Oblast (diverse landscapes, forests, ponds, etc.) and environmental situation, which can be described as “free green west” and “dense smoke-filled east”.

Lyuberetsky District is located in the south-east of Moscow’s green belt and is included into the Central zone of the Moscow Oblast, which represents an almost completely transformed technogenic system with developed industry and transport network. The area is located within the boundaries of one landscape territory – Moscow Meshchera – and its natural vegetation comprises pine forests and broadleaved species, but much of the forest is cut down. According to the level of pollution, the area is unfavorable: the level of air pollution with the most common air contaminants (nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, suspended substances, carbon oxide) can exceed the maximum permissible concentration two times or more. The use of the sludge from Lyubertsy aeration station as a fertilizer was one of the main reasons for soil and water pollution in the area. The condition of soils in the area is considered critical due to the presence of heavy metals and, as a consequence, secondary contamination of atmospheric air. According to the level of pollution and other quality indicators of soils, the landscapes of the area fail to cope with technogenic load. Surface water bodies are also highly contaminated, water quality in the water bodies used for recreational purposes often does not meet sanitary requirements because of the sewage from industrial and agricultural enterprises [20]. Lyuberetsky District is marked as critical on the maps denoting the ecological situation in the Moscow region districts [18].

According to the ecological-economic zoning of the Moscow Oblast, Odintsovsky District is part of the Smolensk-Moscow zone located in the north-west of the Moscow Oblast. The degree of anthropogenic transformation of natural environment within the district is low. The region has considerable natural resources favorable for recreation; agriculture and forestry prevail here, and industry is not developed highly. In this regard, and taking into account the presence of the forest and park zone that performs environment protection functions, the district can be classified as environmentally safe areas of the Moscow Oblast. Forests that perform water protection, sanitary-hygienic and recreational functions are included in the first group. The level of air contamination with the main pollutants (nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, suspended substances, carbon oxide)

in the district does not exceed the maximum permissible concentration. The background pollution level of the atmosphere is favorable. The district ecosystems have preserved the capacity to purify themselves from industrial, transport and agricultural pollution. Basically, the district has satisfactory and favorable environmental conditions for living and leisure, therefore it is among the “elite” places of Moscow suburbs. Here the landscape is able to regenerate itself if environmental works are carried out and the regime of using the territory of specially protected natural and historic and cultural monuments is observed [20]. The environmental maps of the Moscow region districts mark Odintsovsky District as “clean enough” [18].

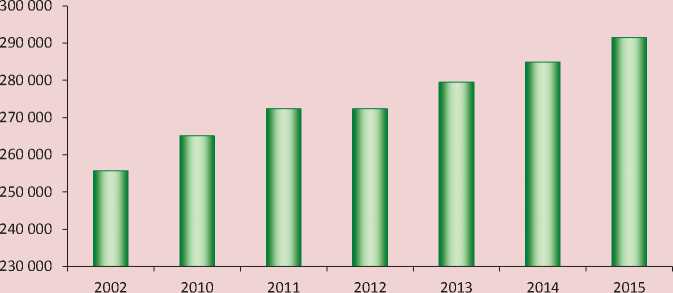

Another component of socio-ecological factors in suburbanization is the attractiveness of dacha areas for the population. Historically, the development of dacha settlements in Lyuberetsky and Odintsovsky districts started in the second half of the 19th century, after the construction of railways. One of the first Russian railway lines (Ryazan direction) went through the city of Lyubertsy in 1860; after that, there swiftly emerged many dacha areas and infrastructure. Some of them (Veshnyaki, Vyhhino, etc.) became part of Moscow in the early 20th century, having lost their functions as dacha settlements; Malakhovka and Kraskovo – the areas more remote from Moscow – strengthened their status as dacha settlements in the period preceding the Great Patriotic War, and now they belong to the category of old dacha settlements. In summer 2014, a mini-survey of 20 respondents who live in such settlements of Lyuberetsky District showed that people are mostly concerned about the “invasion of the city” into traditional dacha settlements, which creates a “mosaic” of low-rise and high-rise blocks. Modern mass housing development is changing the external image of the landscape; high-rise buildings are erected in front of dacha houses, and industrial zones are created nearby. Traditional rural landscapes are vanishing, they do not “fit in” well with the territory and sometimes even endanger life. There are almost no rural residents in the district, and the significant population growth takes place at the expense of new city dwellers (see table; fig. 2).

In Odintsovsky District, due to uniqueness of its nature, “dacha-related activities” quickly began to prevail among other activities, and the local population started to focus exclusively on dacha consumer. As a result, at present, GNPs, DNPs, and SFHS’s occupy about 10% of the district’s total area, and they are located according to a definite pattern: SFHS’s are situated closer to the boundary of Moscow, their density increases along the Moskva River, Mozhayskoye and Minskoye highways. The most expensive and elite SFHS’s are located along the Moskva River and Rublevo-Uspenskoe highway; back in the Soviet period, the luxury suburban residences (“Kremlin dachas”) of high Kremlin officials were situated there, as well as prestigious out-oftown residences in Barvikha, Gorki, Gorki-10, Nikolina Gora and their surroundings [10]. GNPs are located generally according to similar patterns, but some of them are situated near the railway in the Belarus direction. GNPs are distributed most equally, but their density becomes considerably greater as they approach the railway.

In the rural settlement of Zhavoronki in the summer of 2014, twenty problem-oriented interviews were conducted with the residents, they pointed out the social and territorial changes that had occurred in the course of dacha development after the 1960s. All respondents said that as dacha settlements

Figure 2. Dynamics of the number of residents in Lyuberetsky District

Source: compiled by the author according to the data of the Federal State Statistics Service as of 2015 .

were substituted with single family house settlements, the land started to be used for recreational, rather than agricultural, purposes, and natural landscapes become fragmented. Surviving patches of forests, swamps and meadows are being polluted and become garbage dumps, and those that are within transport accessibility are being built up, despite the risk of fire. People were particularly concerned about it in the period of abnormally hot summer: “They blocked the way to the river on the thirtieth kilometer of the road, and now the area that used to be a swamp near the forest where we would pick mushrooms is on the point of smoking...”. Local residents and long-time second homers complained that it is impossible to access forests and water bodies because they are fenced and it is prohibited to pass through protected territories of single family house settlements. Traditional rural landscape of central Russia turned into a geometrically structured pattern with high fences along the highways; “nothing is grown the other side of the fence, there is only a lawn and a gazebo there...”. The inhabitants of single family house settlements usually hire the migrants who settled in the surrounding villages that had become desolated as a result of the natural loss or movement of their residents in the capital.

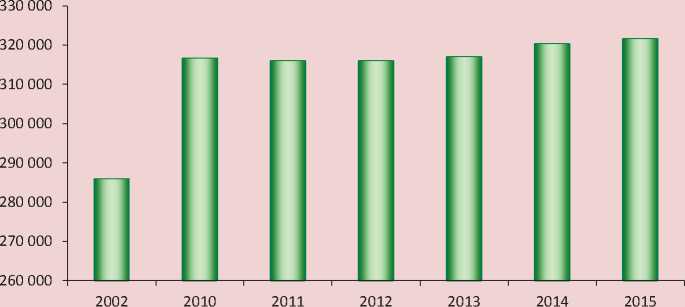

The current structure of dacha settlements helps stabilize the number of the district’s population and retain a significant share of rural residents there (see table; fig. 3 ).

Economic and technological factors influence dacha-related suburbanization in the Moscow District primarily through the transport accessibility of country houses. For those who own a country house in the suburbs close to the city, the convenience and ease of getting to their place of work becomes one of the main points when deciding upon the yearround living in the country, which implies commuting between the home in the country and the office in the city. It becomes important to develop modern means of public transport,

Figure 3. Developments in the number of population in Odintsovsky District

Source: compiled by the author according to the Federal State Statistics Service data for 2015 .

mainly, the subway, which can play a role similar to that of the railway in the late 19th century. However, in high-density areas with a “mosaic” distribution of dacha settlements, the subway may facilitate their replacement by large residential developments, this has happened in Lyuberetsky District. In the near future, it is not planned to build a subway in Odintsovsky District; however, since 1998, a question has been discussed concerning the elimination of the Kuntsevo – Usovo single railway line for the purpose of constructing another motor road as an alternative to the Rublevo-Uspenskoye highway that leads to the most pretentious suburb of the capital.

Moscow suburbs have already witnessed a complete dismantling of the railways in connection with the construction of single family house settlements in their place – it happened in 2008 in Krasnogorsky District between the stations of Nakhabino and Pavlovskaya Sloboda.

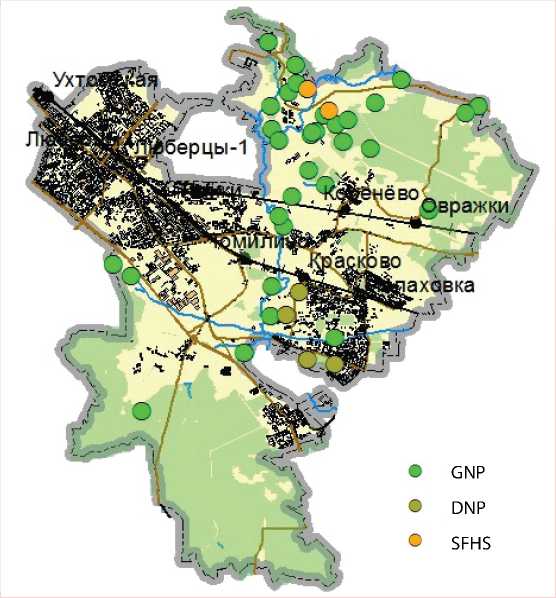

Figure 4 shows that the present-day distribution of dacha settlements in Lyuberetsky District reflects an extremely high level of urbanization there – dacha and gardening associations occupy only 0.13% of the district area. The majority of GNPs are located in the northern part of the district, at some distance from the railroad, and traditional dacha areas

Figure 4. Structure of dacha settlement in Lyuberetsky District

along the railway line of Ryazan direction have been substantially modified through the high-density constriction of multi-storey buildings. In the old dacha settlements of Tomilino, Kraskovo and Malakhovka that form a continuous zone stretching further to the south-east in Ramensky District, there are only few GNPs and DNPs, and they exist alongside high-rise residential buildings and industrial facilities. The system of dacha resettlement in the district, which was in the beginning of its development similar to that of the suburbs located near railways and which lived through its heyday in the pre-war period, changed in subsequent years due to the growth of Moscow: traditional dacha areas became urban residential areas. So far, only Kraskovo retains the official status of dacha settlement, but it has already been greatly modified due to the construction of multi-storey residential buildings there. The northern part of the district can be considered a promising area for the emergence of a modern type of suburban settlements – single family house settlements; but this process is hampered by adverse environmental conditions.

Figure 5 shows that the system of dacha settlements distribution in Odintsovsky District is formed by a large number of dacha settlements of various types, which are widely

Figure 5. Structure of dacha settlements distribution in Odintsovsky District

spread throughout the territory. This causes conflicts connected with the growing high-rise development within traditional dacha areas, and also due to the emergence of new SFHS’s that violate the traditional suburban way of life. A promising process in the system of dacha settlements distribution in the district may be the emergence of new and relatively inexpensive SFHS’s, the in location of which, unlike that of more expensive SFHS’s, is more clearly focused on the accessibility of the railways of the Belarus direction.

The present study conducted on the example of key districts of the suburbs nearest to Moscow shows that dacha settlements distribution of the Moscow Oblast is a type of Russian suburbanization that differs from its classical analog by the seasonality of suburban housing. Dacha suburbanization factors contribute to the heterogeneity of this process, promote the formation of different types of dacha settlements and different prospects, even in areas with common basic characteristics.

Lyuberetsky and Odintsovsky districts of the Moscow Oblast are noteworthy in this regard, because they both are the closest suburbs of the capital and have railroads that were left since the pre-revolutionary period and now serve as an impetus to dacha development. However, in Lyuberetsky District, the prevalence of economic-technological factors, i.e. the development of industry and associated transport infrastructure led to the degradation of dacha development and to gradual absorption of dacha areas by the city. Here the system of dacha settlement distribution, thriving in the pre-war period, has been gradually fading away since the 1960s due to the inclusion of dacha areas in the territory of Moscow and due to their large-scale high-rise development. The pressure from the capital continues, aided by the development of modern high-speed transport; however, dacha settlements are still preserved in the form of several dozen local old dacha settlements scattered in the northern part of the district, where the influence of Moscow is not so great.

Socio-environmental factors such as a unique natural environment and recreational appeal prevail in the dacha settlement distribution in Odintsovsky District. The vast territory of the district has more than five hundred suburban settlements of various types, among which the prestigious SFHS’s play a “dacha-forming” role for the surrounding dacha areas. Due to this fact, the dacha settlements of lower level are under pressure not only from the multi-storey city development, but also from the newly emerging SFHS’s. Currently, a quite clear zoning of SFHS’s, DNPs and GNPs is observed, which indicates their evolution, but the future of dacha settlement distribution depends on the mass character and localization of single family housing construction.

In the theoretical aspect, this work can be used to analyze the issues of suburban settlement and suburbanization in Russian socio-economic conditions based on the suburban settlement factors.

The practical significance of the work is determined by its empirical and applied aspects. The empirical aspect is related to the identification of specific factors determining dacha suburbanization in Russia on the example of the Moscow region. In the applied aspect, the work can be used for developing an algorithm of the universal model for simulating the development of suburban territories.

Список литературы Russian specifics of dacha suburbanization process: case study of the Moscow region

- Aksel'rod K.I. Podmoskovnaya dacha v sovetskoi kul'ture (na primere poselkov tvorcheskoi i nauchno-tekhnicheskoi intelligentsii): dis.. kand. arkhitektury . Moscow: NIITAG RAASN, 2002.

- Zhurenkov K. Dachnyi renessans . Kommersant”.ru. Available at: http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2539155

- Letyagin L.N. Usadebnyi metalandshaft Rossii. /Russkaya usad'ba, 2004, no. 10, pp. 9-18.

- Makhrova A.G. Osobennosti stadial'nogo razvitiya Moskovskoi aglomeratsii . Vestnik MGU. Ser. 5 Geografiya , 2014, no. 4, pp. 10-16.

- Nefedova T.G., Makhrova A.G. Rossiiskie dachi v raznom masshtabe prostranstva i vremeni . Demoskop Weekly , 2015, no. 657-658. Available at: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2015/0657/tema07.php

- Nefedova T.G., Savchuk I.G. Vtoroe zagorodnoe zhil'e gorozhan v Rossii i Ukraine: evolyutsiya dach i trendy ikh sovremennykh izmenenii . Izvestiya RAN. Ser. Geograficheskaya , 2014, no. 4, pp. 39-49.

- Rusanov A.V. Evolyutsiya dachnogo rasseleniya Podmoskov'ya kak element rossiiskoi suburbanizatsii . Problemy regional'noi ekologii , 2014, no. 6, pp. 127-134.

- Treivish A.I. Dachnaya mobil'nost', dachnyi mentalitet i dachevedenie . Demoskop Weekly , 2015, no. 655-656. Available at: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2015/0655/tema07.php

- Toporina V.A. Tipologiya dvoryanskikh usadebno-parkovykh kompleksov tsentral'noi Rossii po razmeshcheniyu v landshafte . Ekologiya urbanizirovannykh territorii , 2011, no. 1, pp. 60-65.

- Sayanov A.A. Kontseptsiya landshaftno-ekologicheskogo proektirovaniya kottedzhnykh poselkov . Ekologiya urbanizirovannykh territorii , 2013, no. 4, pp. 65-69.

- Shapovalov S.S. Tipologicheskoe raznoobrazie dachnykh poselenii kak faktor formirovaniya prigorodnoi zony . Arkhitektura i sovremennye informatsionnye tekhnologii: Mezhdunarodnyi elektronnyi nauchno-obrazovatel'nyi zhurnal , 2010, no. 3 (12). Available at: http://www.marhi.ru/AMIT/2010/3kvart10/shestopalov/abstract1.php

- Ebner M.H. Creating Chicago's North Shore. A Suburban History. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1988. 368 p.

- Gerold J., Drescher A.W., Holmer R. Kleingärten zur Armutsminderung -Schrebergärten in Cagayan de Oro. Südostasien, 2005, no. 21 (4), pp. 76-77.

- Hiltunen Mervi Johanna, Rehunen Antti. Second Home Mobility in Finland: Patterns, Practices and Relations of Leisure Oriented Mobile Lifestyle. Fennia 192, 2014, no. 1, pp. 1-22.

- Lovell S. Summerfolk: A History of the Dacha, 1710-2000. Cornell University Press, 2003. 275 p

- Więcław-Michniewska J. Krakowskie suburbia i ich społeczność. IGiGP UJ, Kraków, 2006.

- Iz istorii administrativno-territorial'nogo deleniya Moskvy . Sait Glavnogo arkhivnogo upravleniya g. Moskvy . Available at: http://mosarchiv.mos.ru/uslugi/spravochniki_po_fondam/Putevoditel-1/prilozhenie.htm

- Karta ekologicheskoi obstanovki raionov Podmoskov'ya . Available at: http://www.zemer.ru/ekologiya-podmoskovya.php

- Chislennost' naseleniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii po munitsipal'nym obrazovaniyam . Sait Federal'noi sluzhby gosudarstvennoi statistiki . Available at:http://www.gks.ru/wps/wcm/connect/rosstat_main/rosstat/ru/statistics/publications/catalog/afc8ea004d56a39ab251f2bafc3a6fce

- Ekologiya Moskvy i Podmoskov'ya . Available at: http://www. ecoanaliz.ru/cat-ecomoscow.html

- Informatsionnyi portal “Severnyi dachnik” . Available at: http://sotok.net/