Securing Drone Communications: A Vulnerability Analysis of MAVLink

Автор: Anuhya Murki, Mahati A. Kalale, Shriya Anil, P. Santhi Thilagam

Журнал: International Journal of Wireless and Microwave Technologies @ijwmt

Статья в выпуске: 6 Vol.15, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly being integrated into a wide range of industries and ap- plications, including but not limited to surveillance, logistics, environmental monitoring, infrastructure inspection, and disaster management. The growing deployment of UAVs in both civilian and defence sectors highlights their versatil- ity and operational efficiency. However, one of the core enablers of UAV functionality is their dependence on wireless communication systems and network protocols to facilitate control, telemetry, and coordination with ground control sta- tions or other UAVs. This reliance on open and often unsecured communication channels exposes UAVs to a variety of significant security threats. This paper focuses on performing a comprehensive vulnerability analysis of the MAVLink protocol, which is currently the most extensively adopted communication protocol for UAVs. We analyse key security weaknesses inherent in the MAVLink protocol’s design, as well as additional vulnerabilities that may arise from specific implementations of the protocol. These vulnerabilities can enable a wide range of potential attacks, including spoofing, message injection, replay attacks, and unauthorised access. In addition, we assess the effectiveness of existing security mechanisms that have been proposed or implemented, such as encryption techniques, authentication frameworks, and intrusion detection systems. By systematically highlighting these vulnerabilities and their real-world implications, this study aims to offer meaningful insights into improving MAVLink protocol security and fostering more resilient and secure UAV communication systems.

UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle), Drone Security, Mavlink, Communication Threats, Network Security

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15020080

IDR: 15020080 | DOI: 10.5815/ijwmt.2025.06.02

Текст научной статьи Securing Drone Communications: A Vulnerability Analysis of MAVLink

MAVLink (Micro Air Vehicle Link) is a lightweight, real-time messaging protocol that plays a crucial role in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) communication, enabling seamless interaction between drones and ground control stations. It is widely adopted due to its efficiency, simplicity, and compatibility with leading autopilot platforms such as PX4 and ArduPilot. MAVLink facilitates essential UAV functions, including telemetry exchange, remote command execution, mission management, and real-time monitoring, making it the de facto standard for UAV communication. However, despite its widespread use, MAVLink was not originally designed with security as a primary focus, leaving it vulnerable to a range of cyber threats. The protocol primarily operates over wireless links, which are inherently susceptible to attacks such as eavesdropping, message spoofing, unauthorised command injection, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. These vulnerabilities, if exploited, can severely impact UAV operations, leading to mission failure, loss of control, or compromised data integrity.

This paper focuses on identifying vulnerabilities within the MAVLink protocol and analysing how these weaknesses expose UAV communication systems to security threats. Instead of solely examining external threats, our approach in- vestigates the protocol-level design flaws that enable these attacks. Despite MAVLink’s efficiency and widespread adop- tion, its lack of built-in encryption and reliance on open wireless channels introduce potential risks, including message interception, unauthorised command execution, and telemetry manipulation. We review existing literature on security en- hancements, such as encryption schemes, authentication mechanisms, and intrusion detection systems (IDS), and assess their effectiveness in addressing MAVLink’s inherent vulnerabilities.

While several UAV communication protocols exist—such as STANAG 4586, UAVCAN, and DDS—this study focuses exclusively on MAVLink due to its widespread adoption in both academic and commercial UAV platforms, including PX4 and ArduPilot. MAVLink is the de facto standard for lightweight, real-time UAV communication, particularly in resource- constrained environments. In contrast, protocols like STANAG 4586 are primarily used in military-grade systems and are often proprietary or classified, limiting their accessibility for open research. Therefore, MAVLink presents a more practical and impactful target for vulnerability analysis in the context of civilian and research-grade UAV systems.

This structured classification and threat analysis aims to provide a clear framework for understanding and mitigating security risks in MAVLink-based UAV communication. The paper begins with an overview of the MAVLink protocol and its role in UAV operations, followed by a detailed examination of its security vulnerabilities and their classification. We then explore potential countermeasures—from cryptographic enhancements to network-level defences—and conclude by discussing future research directions to strengthen MAVLink security. By addressing these vulnerabilities at their root cause, we seek to enhance the resilience of MAVLink-enabled UAV operations against emerging cyber threats, ensuring safer and more reliable drone communication in critical applications.

While this study is grounded in technical analysis and literature, future work should incorporate perspectives from UAV developers, operators, and regulatory bodies to better understand operational constraints and real-world security practices. Such input would provide context-specific insights into MAVLink vulnerabilities and the feasibility of proposed mitigation strategies.

2. Literature Review

Recent studies have provided extensive insights into various aspects of drone security, addressing both general and communication-specific threats.

Mekdad et al. [1] provide a detailed examination of the software, hardware, sensor-based, and communication threats to drones, offering a comprehensive overview of drone security. The paper identifies critical communication-level threats in UAVs across the physical, network, and transport layers, emphasising vulnerabilities like data interception, DoS (Denial-of-Service) attacks, and protocol weaknesses (e.g., MAVLink’s lack of encryption). Adversaries exploit these flaws to disrupt control signals, intercept data, or hijack drones. Suggested solutions include implementing encryption protocols, intrusion detection systems (IDS), and secure routing mechanisms for ad hoc UAV networks. Enhancements like adopting MAVLink v2.0 with message signing, ensuring mutual authentication, and enabling redundant communi- cation channels are recommended to bolster security. However, resource constraints, latency sensitivity, and the need for standardisation remain key challenges in implementing these solutions effectively.

Similarly, Pandey et al. [2] present an in-depth survey of cyberattacks targeting drones, including position-altering threats, software vulnerabilities, and navigational risks. It also suggests various security measures, such as UAV-assisted security and fog computing. Meanwhile, Hassija et al. [3] explore security architectures for drones, highlighting the roles of machine learning (ML), software-defined networking (SDN), and fog computing.

In addition to these broader security concerns, several studies specifically address the threats related to drone commu- nication systems. Gupta et al. [4] examine the security challenges associated with drone routing and handovers, while also proposing protocols aimed at enhancing drone energy efficiency. Wang et al. [5] highlight communication security threats to UAVs, including physical-layer attacks like jamming, eavesdropping, and tampering, and protocol-level vulner- abilities in lightweight protocols like MAVLink, which lack robust encryption and authentication. These issues expose UAVs to DoS attacks, spoofing, and data theft. The paper also proposes solutions to handle these vulnerabilities, such as cryptography (e.g., AES encryption, digital signatures), physical-layer security (e.g., artificial noise to confuse attackers), and intrusion detection systems (IDS) based on anomaly detection. Sathaye et al. [6] provide a detailed account of the implementation and impact of GPS spoofing attacks on drones, along with strategies and countermeasures to mitigate such threats. Sorbelli et al. [7] focus on path deviation attacks within drone communications.

A particular area of interest in drone communication security is the MAVLink protocol, which has been the subject of multiple studies. Kwon et al. [8] highlight the vulnerabilities within MAVLink, while Glossner et al. [9] emphasise the absence of encryption in the MAVLink protocol. Gustafsson et al. [10] provide an overview of UAV protocols, identifying MAVLink as the most suitable option. Koubaˆa et al. [11] focus on MAVLink, discussing its protocol structure, message processing, operational modes, and the security threats associated with it. It details vulnerabilities like the lack of en- cryption and authentication, making the protocol susceptible to threats like eavesdropping, message modification, replay attacks, and DoS attacks. These can lead to compromised confidentiality, integrity, and availability of drone communica- tions. Proposed solutions include hardware-based methods like FPGA modules for encryption and software approaches such as using AES encryption, digital signatures, and message authentication codes (MAC). Emerging techniques like blockchain and intrusion detection systems (IDS) are also proposed to enhance data integrity and detect potential attacks. While these methods improve security, challenges like computational overhead and compatibility with existing systems remain critical barriers.

While there is significant research on drone security, our paper sets itself apart by focusing on identifying the core vulnerabilities within drone systems—both protocol-based and implementation-based. By targeting these vulnerabilities, we aim to better recognise potential mitigations and solutions. Additionally, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the MAVLink protocol, a widely used communication standard in drones, to examine its vulnerabilities. The paper also proposes practical, implementable solutions to address these vulnerabilities, offering actionable insights to enhance the security of drone networks.

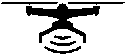

3. UAV Communication Architecture

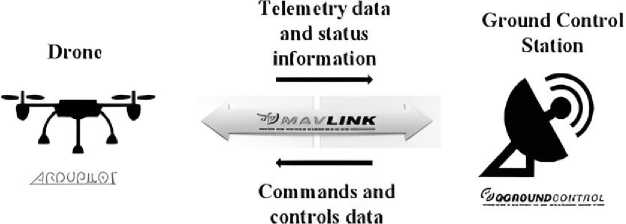

The architecture of a drone system, as shown in Fig.1, encompasses multiple interconnected components that enable its seamless operation, spanning the Ground Control Station (GCS) to the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) platform. The GCS serves as the command-and-control hub, where operators input flight plans, mission objectives, and real-time instructions. It communicates with the UAV platform through wireless links, enabling bidirectional data flow. Commands such as waypoint navigation, speed control, and mission-specific tasks are transmitted to the UAV, while telemetry data, including altitude, battery status, and position, are sent back to the GCS for monitoring. The GCS relies on user-friendly interfaces and often incorporates specialised software to process and visualise data.

UAV

UAV-UAV link

Global Navigation Satellite System

Fig. 1. UAV architecture [12]

The UAV platform is equipped with a variety of subsystems that execute the instructions from the GCS. Key compo- nents include the flight controller, which acts as the central processing unit, integrating inputs from the GCS, onboard sen- sors, and navigational tools such as GPS. The propulsion system, comprising motors and propellers, executes movement commands. Additional sensors like inertial measurement units (IMUs), cameras, and environmental detectors provide real-time situational awareness and data collection. Communication between the GCS and UAV platform is facilitated through standardised protocols, ensuring the reliable exchange of control and data signals.

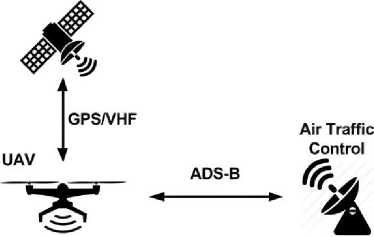

MAVLink (Micro Air Vehicle Link) plays a crucial role in enabling seamless communication between the GCS and UAV, as shown in Fig.2. MAVLink is a lightweight, message-based protocol that transmits telemetry, mission commands, and status updates between the drone and its operator. It supports both high-level mission management (e.g., setting waypoints and autonomous navigation) and low-level real-time control (e.g., adjusting flight parameters and executing emergency manoeuvres). The protocol ensures that data is exchanged efficiently over low-bandwidth links, making it ideal for UAV operations. Additionally, MAVLink’s compatibility with major autopilot platforms like PX4 and

ArduPilot allows for widespread adoption across different drone systems. By standardising communication between the GCS and UAV, MAVLink enhances the reliability and flexibility of drone operations, facilitating real-time decisionmaking and mission execution across various domains, including aerial surveillance, mapping, and autonomous navigation.

Fig. 2. Drone communication using MAVLink

-

3.1. MAVLink Protocol

-

3.2. MAVLink versions

MAVLink is a widely used lightweight binary serialisation protocol designed for unmanned vehicle systems, including drones. Its efficient design minimises communication overhead by transforming messages into compact byte sequences, making it significantly more resource-friendly than formats like XML or JSON. MAVLink’s lightweight nature also allows it to support a variety of transport layers and mediums, enhancing its versatility in UAV operations.

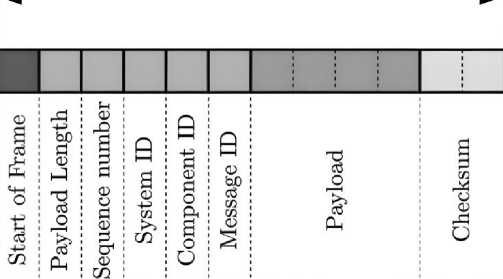

Each MAVLink message comprises two main components: the header, which contains metadata about the message (such as its type and routing information), and the payload, which carries the data being transmitted as shown in Fig.3. This modular structure enables MAVLink to facilitate UAV-GCS (Ground Control Station) communication efficiently, handling a range of tasks such as telemetry data exchange, mission commands, and flight control.

MAVLink Frame (8-263 bytes)

Fig 3. MAVLink protocol data frame structure

MAVLink has evolved from its original version (MAVLink 1) to a more advanced and secure version (MAVLink 2). In MAVLink 1, the header includes fields such as Message Length, Sequence Number, System ID, Component ID, and Message ID, allowing for basic UAV-to-GCS communication. MAVLink 2 extends this structure by introducing 24-bit Message IDs, Compatibility Flags (INC FLAGS) for protocol extensions, Incompatibility Flags (CMP FLAGS) for feature enforcement, and an optional 13-byte Signature for authentication, enhancing security and flexibility. This structured header ensures reliable, low-latency communication over bandwidth-constrained links.

MAVLink messages are categorised into different types based on their functionality. Heartbeat messages maintain the connection status between the UAV and the ground control station. System status messages provide information about on- board sensors, battery levels, and system health. GPS messages relay global positioning data, such as latitude, longitude, and altitude, enabling navigation. Command messages allow the GCS to control the UAV, issuing actions like TAKEOFF, LAND, or ARM/DISARM. Mission-related messages manage waypoints and flight plans, ensuring autonomous navi- gation. Additionally, sensor data messages provide telemetry from onboard instruments such as IMUs and barometers. These categorised messages facilitate seamless UAV operation, supporting both manual control and autonomous flight.

4. Vulnerabilities in MAVLink Protocol

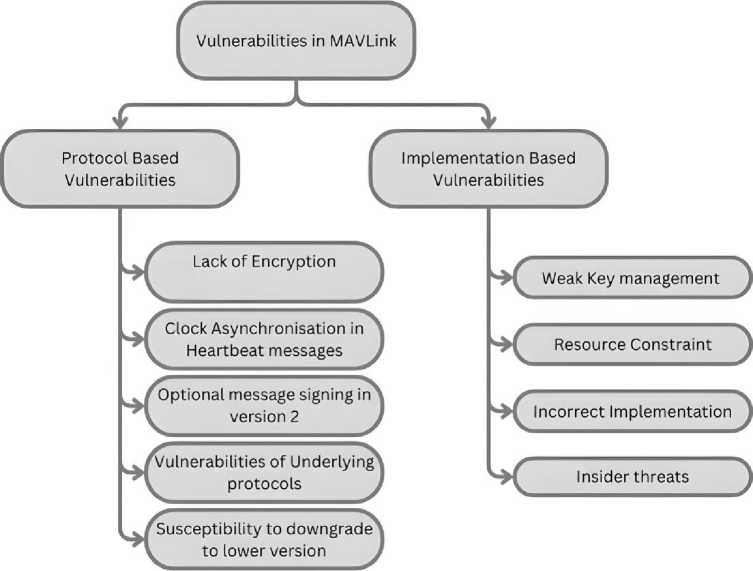

Addressing security threats in UAV communication requires a fundamental understanding of the vulnerabilities within the underlying protocol rather than merely deploying reactive defences against potential attacks. Many security threats arise due to inherent weaknesses in the communication protocol itself, while others emerge from the way the protocol is implemented in specific systems. Identifying and classifying these vulnerabilities provides a more effective approach to securing UAV communication, as it allows for targeted mitigation strategies that address the root causes of security risks.

In the case of MAVLink, some vulnerabilities stem from its design choices, such as the lack of built-in encryption in MAVLink v1, making it susceptible to message interception and spoofing. Other vulnerabilities arise from the way MAVLink is integrated into drone systems, such as improper key management or insecure wireless transmission methods. To systematically analyse these risks, we classify MAVLink vulnerabilities into two categories as shown in Fig.4: protocol-based vulnerabilities, which originate from the MAVLink specification itself, and implementation-based vulner- abilities, which result from how MAVLink is deployed in real-world UAV systems. By examining each category in detail, we aim to uncover the security gaps in MAVLink communication and propose effective countermeasures to enhance UAV security.

Fig. 4. Vulnerabilities in MAVLink protocol

-

4.1. Protocol-based vulnerabilities

-

4.1.1 Lack of Encryption

-

4.1.2 Clock asynchronisation in heartbeat messages

Protocol-based vulnerabilities arise due to inherent design choices and limitations within the MAVLink protocol itself, rather than specific implementation flaws. These vulnerabilities stem from the protocol’s focus on being lightweight and efficient, often at the expense of security features such as encryption, authentication, and integrity checks. Since MAVLink was originally designed for real-time UAV communication with minimal overhead, security mechanisms were either omitted or made optional to maintain performance, making it susceptible to various attacks.

MAVLink, by design, does not include encryption for its communication channels. This is primarily because it was de- veloped as a lightweight protocol optimised for low-latency and low-bandwidth communication, making it highly efficient for UAVs and other robotic systems. Encryption typically introduces computational overhead, which can be challenging for resource-constrained embedded systems like flight controllers and companion computers. Additionally, MAVLink was originally designed for environments where security was not a primary concern, assuming that communication links were inherently trusted. While MAVLink 2 introduced message signing to verify the authenticity of messages, it does not provide encryption. This means that while message tampering can be detected to some extent, the content of MAVLink messages remains unencrypted and exposed to anyone who can intercept the communication.

Eavesdropping : Since MAVLink messages are transmitted in plaintext, an adversary with access to the communication channel (e.g., an attacker using a software-defined radio or network sniffer) can intercept and read sensitive UAV data. This includes telemetry data, flight commands, sensor readings, and mission parameters. This is particularly dangerous in military, industrial, and surveillance applications where UAVs transmit sensitive information.

Command injection and spoofing : Because MAVLink messages are not encrypted or authenticated (apart from optional signing in MAVLink 2), attackers can inject malicious commands by spoofing MAVLink packets. For example, an attacker could send unauthorised commands to change flight paths, disable the UAV, or hijack its mission. Even with message signing in MAVLink 2, if the secret key is compromised or poorly managed, an attacker could forge legitimatelooking messages. Empirical studies have shown that command injection attacks on MAVLink v1 have a success rate of approximately 90-95%, with negligible latency impact. This high success rate underscores the critical need for encryption and authentication mechanisms in MAVLink-based systems.

MAVLink relies on timestamps for various message validation processes, including preventing replay attacks and maintaining message integrity. However, MAVLink-enabled devices often do not have access to a globally synchronised time source (such as GPS-based timestamps), leading to potential clock skew between different MAVLink nodes. In MAVLink, heartbeat messages are periodic status signals exchanged between components (e.g., Ground Control Station (GCS), autopilot, and companion computers). These messages typically contain timestamps to indicate the sender’s current time. However, if different components operate on unsynchronised clocks, their timestamps may drift apart, causing message validation failures or exploitation by attackers. MAVLink 2 uses timestamps within message signatures to prevent replay attacks, but if the timestamps are not strictly monotonic or properly managed, attackers can exploit clock discrepancies to either replay or discard valid messages.

Replay attacks : If a MAVLink node does not enforce strict timestamp validation, an attacker could capture a valid signed packet and replay it at a later time. The UAV or GCS may process old commands as if they were new, leading to unintended actions such as repeating mission-critical commands (e.g., returning to home, changing altitude) or providing old sensor data, misleading the operator and potentially causing poor decision-making.

Message discarding : If a receiver detects that an incoming MAVLink packet has a timestamp older than its last received packet, it may discard the packet, assuming it is outdated. A legitimate command or telemetry update may be unintentionally dropped, leading to operational disruptions. Critical data (e.g., battery status, obstacle detection) may be ignored, causing the UAV to operate on outdated information.

-

4.1.3 Optional message signing in MAVLink Version 2

-

4.1.4 Vulnerabilities of underlying protocols

MAVLink 2 introduced message signing to verify the authenticity of messages and prevent spoofing. However, sign- ing remains optional, meaning that not all MAVLink implementations enforce it. This allows attackers to exploit systems that either do not implement signing or fail to properly configure signature validation. Without a strict requirement for au- thentication, UAV communication remains vulnerable to unauthorised message injection and spoofing attacks. Even when signing is enabled, the current implementation presents several weaknesses. First, signatures are not encrypted, meaning they help verify authenticity but do not prevent eavesdropping. Attackers can still intercept communication, potentially gathering intelligence about drone operations. Furthermore, since message signing is optional, some implementations may still process unsigned packets, exposing them to injection attacks. Another weakness lies in signature truncation or removal—if a receiver does not strictly validate signatures, an attacker could remove or modify them, causing the system to accept potentially forged packets.

Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks : Without encryption and strict authentication, an attacker can intercept and modify MAVLink messages in real time. This allows them to alter telemetry data sent to the Ground Control Station (GCS) or modify commands sent to the UAV, causing operators to make incorrect decisions based on tampered data.

Despite its introduction in MAVLink 2, message signing remains optional and inconsistently adopted across platforms. This limited uptake is often due to resource constraints and a lack of standard enforcement policies. A potential mitigation strategy is to mandate signing for critical message types (e.g., command and telemetry) and enforce signature validation at both GCS and UAV endpoints, supported by secure key provisioning frameworks.

MAVLink operates over various underlying transport protocols, such as UDP, TCP, Wi-Fi, or serial links. While MAVLink itself is focused on lightweight messaging for UAV communication, it inherits the security weaknesses of these transport mechanisms. If an attacker exploits vulnerabilities in the underlying protocol, they can disrupt MAVLink communication, intercept messages, or launch denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, severely impacting UAV operations. For example, UDP is a connectionless protocol that does not perform error-checking or retransmission. While this reduces latency, it also leaves MAVLink traffic vulnerable to spoofing, injection, and flooding attacks. Similarly, if MAVLink is transmitted over Wi-Fi, it is susceptible to network-layer attacks such as packet sniffing, jamming, and deauthentication.

SYN flood attacks : If MAVLink is transmitted over TCP, an attacker can initiate a SYN flood attack, where they send a large number of half-open connection requests to the server (e.g., Ground Control Station or UAV). This exhausts system resources, preventing legitimate MAVLink commands from being processed, leading to loss of UAV control.

UDP flooding : Since UDP does not require a handshake, an attacker can flood the UAV or GCS with excessive MAVLink messages. This overloads the system, causing packet loss, delayed responses, or complete communication failure, potentially grounding the UAV. In simulated denial-of-service (DoS) scenarios using UDP flooding, UAV systems experienced 100% success in disrupting communication, with latency spikes of 2-5 seconds and temporary GCS unresponsiveness. These results highlight the ease with which attackers can exploit MAVLink’s reliance on insecure transport layers.

Wi-Fi deauthentication attacks : If MAVLink communication relies on Wi-Fi, an attacker can send deauthentication packets, forcing the UAV or GCS to disconnect from the network. This disrupts command and telemetry exchange, leading to loss of real-time monitoring or even a UAV crash if emergency control mechanisms are absent.

-

4.1.5 Susceptibility to downgrade to lower MAVLink version

-

4.2. Implementation-based vulnerabilities

-

4.2.1 Weak Key Management

MAVLink 2 was designed with backwards compatibility in mind, allowing it to communicate with systems that still use MAVLink 1. This ensures that older UAV components can still function without requiring a full system upgrade. However, this backwards compatibility introduces a security risk, as an attacker can force a UAV system to downgrade from MAVLink 2 to MAVLink 1, stripping away critical security features such as message signing. MAVLink 1 does not include any authentication or integrity protection, meaning it is fully vulnerable to spoofing, injection, and man-in- the-middle (MitM) attacks. By forcing a downgrade, attackers can bypass MAVLink 2’s optional security mechanisms, making UAV communication significantly more susceptible to attacks.

Spoofing and command injection : Once downgraded to MAVLink 1, the system will accept unsigned packets, making it easy for attackers to spoof legitimate messages. The UAV may receive unauthorised commands, such as changing flight paths, disabling security measures, or even forcing an emergency landing.

Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks : MAVLink 1 does not have message authentication or encryption, making it easy for an attacker to intercept and modify MAVLink packets in real time. A malicious actor could alter telemetry data being sent to the Ground Control Station (GCS), misleading the operator about the drone’s actual status.

While protocol-based vulnerabilities stem from the inherent design of MAVLink (e.g., lack of encryption or optional message signing), implementation-based vulnerabilities arise from how these features are configured, deployed, or en- forced in real-world systems. For example, although MAVLink 2 supports message signing, its security depends on correct key management and strict validation—factors that are implementation-specific.

Implementation-based vulnerabilities in MAVLink stem from how the protocol is integrated and configured within UAV systems rather than inherent flaws in the protocol itself. These vulnerabilities often arise due to misconfigurations, insecure deployment practices, or hardware limitations that prevent proper enforcement of security measures. Unlike protocol-based vulnerabilities, which affect all MAVLink implementations uniformly, implementation-based weaknesses vary across different systems, depending on factors such as developer decisions, security awareness, and resource availability. Poor implementation can lead to gaps in authentication, encryption, and access control, making UAV communication susceptible to external threats. Additionally, constraints in computational power, memory, or network bandwidth may result in security features being disabled or improperly executed, further exposing the system to attacks. Addressing these vulnerabilities requires strict adherence to security best practices, regular security audits, and careful design choices to ensure that MAVLink is deployed in a way that minimises risk without compromising performance.

Although MAVLink 2 introduces message signing at the protocol level, its effectiveness depends entirely on how the signing keys are managed and stored in practice. Weak key management is thus an implementation-level issue, even though it relates to a protocol feature. If a key is compromised, an attacker can forge valid MAVLink messages, rendering message authentication ineffective. Many UAV systems lack secure key storage mechanisms, especially on resource- constrained embedded devices, which may store keys in plaintext or easily accessible locations. Additionally, improper key distribution (e.g., using the same key across all devices indefinitely) increases the risk of compromise, as a single exposed key could be used to attack multiple UAVs. Without proper key rotation or renewal policies, an attacker who obtains a key can continue exploiting the system indefinitely.

A notable example of weak key management was observed in a study by Kwon et al. [8], where the shared symmetric key used for MAVLink message signing was stored in plaintext on the UAV’s onboard memory. This allowed attackers with physical or remote access to extract the key and forge valid MAVLink packets. Similarly, in open-source implementations like ArduPilot, early versions lacked secure key provisioning mechanisms, often relying on hardcoded or default keys across multiple devices. This practice significantly increases the risk of key compromise, especially in fleet deployments where a single exposed key can jeopardise all UAVs using the same configuration.

-

4.2.2 Resource Constraint

-

4.2.3 Incorrect implementation

In real-world UAV deployments, especially those involving small drones or swarms, resource constraints are a critical barrier to implementing robust security mechanisms. Many UAVs operate on microcontrollers with limited

RAM (e.g., 256 KB) and CPU frequencies below 100 MHz, which restrict their ability to perform cryptographic operations like AES- GCM or run machine learning-based intrusion detection systems. For instance, enabling message signing in MAVLink 2 requires additional memory for key storage and CPU cycles for signature generation and verification—resources that may already be fully utilised by flight control algorithms and sensor data processing. Moreover, power consumption is a major concern in battery-operated UAVs; adding encryption or IDS modules can reduce flight time by 5–10%, which is unacceptable in mission-critical applications. These constraints often force developers to disable or simplify security features, leaving UAVs vulnerable despite protocol-level support for protection.

Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks : An attacker can flood the UAV or Ground Control Station (GCS) with a high volume of MAVLink messages, exhausting CPU and memory resources. Thus, the system may become unresponsive, preventing legitimate commands from being processed, effectively grounding the UAV. Since many MAVLink implementations use low-power wireless links, an attacker could send excessive noise signals or bogus packets, overwhelming the radio module or communication buffer. This disrupts real-time UAV control, potentially leading to mission failure or crashes.

Message validation overload : If a system enforces message signing, verifying cryptographic signatures requires addi- tional CPU cycles. An attacker could send a flood of signed packets, forcing the system to spend excessive time verifying signatures, leading to delays in processing legitimate commands.

Table 1. Vulnerabilities and threats to MAVLink

|

Category |

Vulnerability |

Threats it Leads To |

Security Principle Violated (CIA) |

|

Protocol-Based |

Lack of Encryption |

Eavesdropping, data interception |

Confidentiality |

|

Clock asynchronisation in heartbeat messages |

Disrupted communication, desynchronisation attacks |

Availability, Integrity |

|

|

Optional message signing in Version 2 |

Message spoofing, Unauthorized command injection |

Integrity, Confidentiality |

|

|

Vulnerabilities of underlying protocols |

Exploitation of transport layer weaknesses (e.g., UDP attacks) |

Confidentiality, Integrity |

|

|

Susceptibility to downgrade to lower versions |

Downgrade attacks leading to the removal of security features |

Integrity, Confidentiality |

|

|

ImplementationBased |

Weak Key Management |

Compromised authentication, unauthorised access |

Confidentiality, Integrity |

|

Resource Constraint |

Security features disabled, making the system more vulnerable |

Availability, Integrity |

|

|

Incorrect implementation |

Unintended security flaws, making the system exploitable |

Integrity, Confidentiality |

|

|

Insider threats |

Malicious actions by authorised users, unauthorised access |

Confidentiality, Integrity |

Incorrect implementation occurs when developers fail to correctly integrate MAVLink security mechanisms due to misconfigurations, programming errors, or misunderstandings of the protocol’s security features. While MAVLink 2 provides optional message signing for authentication, its effectiveness depends on how well it is implemented in UAV systems. If developers improperly configure message validation, fail to enforce signing, or introduce software bugs in MAVLink parsing, it can create critical security gaps that attackers can exploit. These issues do not stem from the MAVLink specification itself but from how developers interpret and implement it. For instance, failing to enforce signature validation or accepting unsigned packets is not a protocol flaw but a misconfiguration in the deployment. Additionally, MAVLink is often used in custom-built UAV systems, where different developers may implement the protocol in slightly different ways. These inconsistencies can lead to systems accepting unauthorised messages, failing to detect security breaches, or crashing due to malformed packets.

Inconsistent security across MAVLink components : If different components (e.g., autopilot, GCS, companion computers) implement MAVLink security inconsistently, an attacker could exploit weaker components to inject commands or manipulate telemetry data. For example, if the GCS enforces message signing but the UAV does not, an attacker could send unauthenticated messages directly to the UAV, bypassing security measures.

Bypassing security features : If developers incorrectly implement message signature validation, an attacker may be able to send maliciously modified packets that bypass integrity checks. For example, a UAV may mistakenly accept an altered MAVLink packet, leading to false telemetry reports or erroneous system behaviour.

4.2.4 Insider threats

5. Empirical Evidence and Real-World Validation

6. Countermeasures and mitigation strategies

Insider threats occur when authorised individuals, such as UAV operators, engineers, or developers, intentionally or unintentionally compromise security. In the case of MAVLink, this can happen if an insider leaks, misuses, or improperly stores cryptographic signing keys, allowing an attacker to forge valid signed messages. Unlike external cyberattacks, insider threats are particularly dangerous because they originate from trusted individuals who already have access to critical systems and may bypass traditional security defences. MAVLink 2 relies on a shared symmetric key for message signing. If an insider exposes this key (e.g., through negligence, social engineering, or malicious intent), an attacker can sign and inject forged MAVLink packets, making them appear legitimate. Additionally, insiders with privileged access can intentionally disable security mechanisms, create backdoors, tamper with data or manipulate UAV operations for personal or financial gain.

While this study primarily focuses on theoretical and literature-based analysis of MAVLink vulnerabilities, several real-world experiments and simulations conducted by prior researchers substantiate the feasibility of the attacks discussed. Kwon et al. [8] conducted an empirical analysis of MAVLink vulnerabilities using a PX4-based UAV system and demonstrated successful command injection and telemetry spoofing attacks. Their experiments showed that MAVLink v1, lacking encryption and authentication, allowed attackers to hijack UAV control by injecting forged packets over a wireless link. Similarly, Sathaye et al. [6] validated GPS spoofing attacks in a controlled UAV environment, highlighting the ease with which UAVs can be misled using falsified location data.

To further contextualise these findings, Table 2. summarises key real-world attack scenarios and their outcomes as reported in the literature:

Table 2. Real-world MAVLink attack scenarios and outcomes

|

Attack Type |

Study Reference |

Outcome |

|

Command Injection |

Kwon et al. |

UAV accepted spoofed commands, enabling unauthorised flight path changes. |

|

Telemetry Spoofing |

Kwon et al. |

Ground station received falsified data, misleading operator decisions. |

|

GPS Spoofing |

Sathaye et al. |

UAV deviated from the mission path due to falsified GPS signals. |

|

Replay Attack |

Jeong et al. |

Replayed MAVLink packets caused repeated execution of critical commands. |

These studies validate the theoretical vulnerabilities outlined in this paper and demonstrate their practical exploitability in real-world UAV systems. The consistency between theoretical analysis and empirical outcomes reinforces the urgency of implementing robust security mechanisms in MAVLink-based communication.

Various security countermeasures and mitigation strategies have been proposed to address vulnerabilities in the MAVLink protocol. These approaches can be categorised based on their security objectives: confidentiality, integrity, availability, and authentication.

-

6.1. Cryptographic solutions

-

6.2. Authentication mechanisms

Encryption protocols: One major issue with MAVLink is the lack of built-in encryption, making it vulnerable to eaves- dropping and unauthorised message injection. To address this, encryption layers can be applied to protect communication confidentiality while ensuring efficient performance in resource-constrained UAVs.

A widely used method is AES-GCM (Advanced Encryption Standard in Galois/Counter Mode), which offers both encryption and authentication. Butcher et al. [13] demonstrated that AES-GCM increases security with only an 8-12% latency increase, making it a practical choice for real-time applications. The hardware-accelerated implementation of AES further reduces computational overhead.

An alternative is ChaCha20-Poly1305, a stream cypher designed for software efficiency. Unlike AES, which relies on block-based encryption, ChaCha20 is optimised for general-purpose processors and performs better in embedded UAV systems without dedicated cryptographic hardware. Research by Domin et al. [14] found that ChaCha20-Poly1305 offers superior performance in lightweight drone communication while maintaining strong security guarantees.

AES-GCM encryption introduces an estimated 8–12% increase in CPU load, while ChaCha20-Poly1305 offers similar security with only a 5–8% overhead, making it more suitable for embedded UAV systems [13, 14]. These tradeoffs are acceptable in most real-time UAV applications, given the significant security benefits.

AES-GCM and ChaCha20-Poly1305 offer strong encryption and authentication, their deployment in UAV systems is not without challenges. Many UAVs operate on microcontrollers or embedded processors with limited computational resources and power budgets. ChaCha20-Poly1305 is more suitable for software-only environments, but still requires careful tuning to avoid latency spikes during high-throughput telemetry or video streaming. Additionally, secure key exchange and storage mechanisms must be implemented, which adds further complexity to lightweight UAV firmware.

Enhanced Message Authentication: MAVLink 2 introduced optional message signing, but it remains optional, leaving many implementations vulnerable to message spoofing. To enhance authentication, BLAKE2 has been proposed as a more efficient alternative to SHA-256.

BLAKE2 provides security comparable to SHA-256 but with 30% lower computational overhead, making it suitable for UAVs with limited processing power [15]. Additionally, BLAKE2s generates shorter message signatures (16 bytes instead of 32), reducing bandwidth consumption. Another key advantage of BLAKE2 is its resistance to length extension attacks, which improves security over traditional cryptographic hashes. By integrating BLAKE2-based authentication, MAVLink messages can be protected against forgery and unauthorised modifications.

In comparative evaluations, BLAKE2 has demonstrated approximately 30% lower computational overhead than SHA- 256 while maintaining equivalent cryptographic strength. This makes it particularly suitable for UAVs with limited pro- cessing capabilities. Moreover, BLAKE2s produces shorter signatures (16 bytes), reducing bandwidth usage in MAVLink messages. However, its adoption requires firmware-level integration and consistent enforcement across all MAVLink nodes, which may be challenging in heterogeneous UAV fleets.

-

6.3. Blockchain-based security solutions

-

6.4. Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS)

-

6.4.1 Machine Learning-based detection

-

Blockchain technology provides tamper-resistant security mechanisms for UAV communications by creating an im- mutable log of commands and operations.

Secure Command Authentication prevents unauthorised command injection by recording critical UAV commands on a blockchain before execution. Bera et al. [16] demonstrated that this approach effectively prevents unauthorised control of drones.

Tamper-Evident logging ensures flight data remains immutable by storing logs in a blockchain-based database (e.g., DroneChainDB). Lee et al. [17] proposed DroneChainDB as a forensic tool for analysing UAV security breaches.

Decentralised authentication improves resilience against single-point failures by using blockchain for peer-to-peer authentication in multi-drone systems [18]. This ensures that UAVs can verify each other’s identity without relying on a central authority.

Smart contracts for Mission Authorisation automate security policies to enforce access control before executing UAV commands. Ferrag et al. [19] demonstrated how smart contracts validate mission rules, preventing unauthorised devia- tions.

Despite its promise, blockchain integration in UAV systems faces significant feasibility constraints. Blockchain frameworks typically require persistent storage, continuous connectivity, and consensus mechanisms—all of which are resource-intensive. UAVs with limited onboard memory and intermittent network access may struggle to maintain blockchain nodes or participate in consensus protocols. Moreover, the latency introduced by blockchain transaction validation can be incompatible with the real-time demands of UAV command and control. Lightweight or hybrid blockchain models (e.g., off-chain logging with periodic synchronisation) may offer a compromise, but their security guarantees are still under active research.

Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) monitor MAVLink traffic for anomalies, helping to detect cyberattacks before they compromise UAV operations.

Anomaly Detection involves learning normal MAVLink communication patterns and flagging deviations. Mitchell and Chen [20] developed a behavioural model that achieved 97% accuracy in detecting command injection attacks while maintaining a false positive rate below 3%.

Deep Learning Approaches, such as CNN-LSTM models, analyse temporal MAVLink patterns to detect subtle cyber- attacks that traditional rule-based systems miss. Sedjelmaci et al. [21] showed that a deep learning-based IDS achieved 94% accuracy in detecting zero-day attacks.

Federated Learning allows distributed UAV networks to train IDS models collaboratively without sharing raw data, improving privacy while enhancing attack detection [22].

Among IDS techniques, machine learning-based models such as CNN-LSTM have shown high detection accuracy (up to 94%) for zero-day attacks [21], while maintaining a false positive rate below 5%. However, these models require signif- icant training data and computational resources, which may not be feasible for all UAV platforms. Lightweight anomaly detection models, though less accurate, offer better real-time performance and lower energy consumption, making them more practical for deployment on embedded UAV systems.

6.4.2 Specification-based detection

7. Conclusion and Future Scope

Rule-based detection methods rely on predefined MAVLink message sequences to detect attacks.

Protocol state monitoring tracks MAVLink message sequences to identify unexpected behaviours. Kwon et al. demon- strated that protocol state monitoring effectively detects replay and injection attacks.

Semantic analysis verifies MAVLink commands against the current flight context to detect unsafe or malicious instructions. Kim et al. [23] developed a semantic verification system that identifies suspicious commands even when they appear to be syntactically valid.

A combination of encryption, authentication, blockchain-based logging, and intrusion detection can significantly en- hance the security of MAVLink-based UAV communication. Although AES-GCM and ChaCha20 provide encryption for confidentiality, BLAKE2-based authentication strengthens integrity and authenticity. Blockchain technology intro- duces tamper-proof security, and machine learning-based IDS improves real-time attack detection. By integrating these countermeasures, UAV systems can become more resilient to cyber threats while maintaining operational efficiency.

Specification-based IDS approaches, such as protocol state monitoring and semantic analysis, offer the advantage of low computational overhead and deterministic behaviour. For instance, Kwon et al. demonstrated that protocol state monitoring could detect replay and injection attacks with minimal resource usage. However, these methods may struggle to detect novel or obfuscated attack patterns, limiting their effectiveness in dynamic threat environments.

While various security solutions, such as blockchain-based authentication, intrusion detection systems (IDS), and machine learning-based anomaly detection, offer significant enhancements to MAVLink security, cryptographic solutions remain the most fundamental in securing UAV communication. Blockchain ensures tamper-proof logging, IDS detects anomalies in real time, and ML-based models improve adaptive threat detection. However, these solutions primarily mitigate attacks after they occur or improve security monitoring, whereas cryptographic methods proactively prevent security breaches at their root. The primary vulnerabilities in MAVLink, such as lack of encryption, weak authentication, message spoofing, and downgrade attacks, stem from inadequate cryptographic protections. Without strong encryption, robust authentication mechanisms, and secure key management, MAVLink communication remains inherently exposed to threats, regardless of additional detection-based measures.

Future research should focus on evaluating lightweight cryptographic schemes tailored for embedded UAV systems, developing standardised key management protocols, and designing adaptive intrusion detection models that balance ac- curacy and resource efficiency. Methodologies may include simulation-based testing using PX4 SITL, field trials with ArduPilot, and collaborative studies with UAV manufacturers to validate security frameworks under operational condi- tions.