Shaman tambourines of the northern Ob Ugrians (18th to early 21st centuries)

Автор: Baulo A.V.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: Ethnology

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Shaman tambourines of the northern Khanty and Mansi (18th to early 21st centuries) are described. Sources include publications by other specialists and the author's fi eld materials collected in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra and the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. A shaman performing rites with a tambourine is called koipyng-nyait. The process of making a tambourine is described. Information on 44 tambourines is summarized in a table with reference to shape, number of resonators, etc. The few available descriptions of rites are provided. A separate section concerns anthropomorphic images of patron spirits, carved on handles and beaters or represented as figurines inserted in tambourines. The Lyapin Mansi practiced a custom of providing tambourines with figurines of guards, koipyng-pupyg. Traditionally, after the tambourine's owner had died, the tambourine became a family patron spirit, whose image was supplied with specially sewn men's clothes. In my view, the northern Ob Ugrian shamanism was underdeveloped, as evidenced by the shaman's limited functions, absence of special attire, etc. The shamanic paraphernalia used by Khanty and Mansi are much scarcer than those associated with the cult of Mir-Susne-Khum. The main distribution areas of tambourines in the 20th to early 21st centuries are the basins of the Lyapin River (Mansi) and the Synya River (Khanty). Both belonged to the territory that, in the 18th–19th centuries, was the contact zone between Ob Ugrians and Nenets.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145147222

IDR: 145147222 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.3.99-109

Текст научной статьи Shaman tambourines of the northern Ob Ugrians (18th to early 21st centuries)

The term “shamanism” first appeared in the Russian sources no later than 1648. According to S.V. Bakhrushin, the identification of a special category of people possessing the gift of communicating with spirits from above— “knowledgeable shamans” or shaitanshchiki (‘servants of the shaitan’) (1935: 29, 30)—generally refers to the 17th century. In the early 18th century, mentioned in the sources are shamanchyki (‘shamans’), zhretsy (‘pagan priests’), and volshebniki (‘sorcerers’) (Novitsky, 1884: 48), and in the late 18th century, shamany (‘shamans’), volkhvy (‘soothsayers’), and vorozhei (‘fortune tellers’) (Zuev, 1947: 41). In the 18th to mid-19th centuries, references to shamanic tambourines were sporadic:

“…shamans are appointed… from those who frequently interpret dreams… however, this is not enough, because without any knowledge from previous sorcerers and without using a tambourine, he cannot embark upon such a fearful task for them” (Ibid.: 43); “During their rituals and sacrifices, male and female shamans appear wearing a special outfit, unique to them, with a tambourine in their hands” (Belyavsky, 1833: 115); “A shaman… needs a magic tambourine. Ordinary speech does not reach the ears of the gods; he must converse with them by singing and beating a tambourine” (Kastren, 1860: 187).

The shamanism of the Ob Ugrians is known to be a debated topic in ethnography. The scholars considering it underdeveloped include K. Karjalainen, V.N. Chernetsov, E.D. Prokofieva, and V.M. Kulemzin, who believed

that shamanism among the Mansi and Khanty had less pronounced forms than among other Siberian ethnic groups (Sokolova, 2009: 641). According to Z.P. Sokolova, the shamanism of the Ob Ugrians “developed in the same vein as among other peoples of Siberia (but was not more weakly developed), and it has lost a number of features or disappeared only under the influence of the early entry of Western Siberia into Russia, and Christianization” (Ibid.: 652–654).

The author of this article agrees with the point of view about underdeveloped shamanism among the northern Ob Ugrians. The figure of the shaman did not play a primary role among them, since their ritual practices had the character of home sanctuaries where the owner of the house acted as an intermediary between people and spirits in everyday life and during the ritual. A shaman had the task of communicating with spirits in critical (illness, loss, or natural disaster) or borderline (fortune telling at the birth of a child or at the coffin of the deceased) situations. According to the evidence of the 20th century, shamans or their attributes were observed mainly along the western and eastern periphery of the “Vogul” wedge, in the contact zones of the Ugrians and Samoyeds (the upper reaches of the Lyapin and Synya rivers; the Kazym River basin), which suggests the Nenets influence. However, scholars did not observe the full shaman’s outfit (headdress, robe, and footwear) among them. The main attribute of a shaman confirming his status among the northern Ob Ugrians was the tambourine.

This article examines the evidence only on the northern Mansi and Khanty, since first, their shamanism differs in many ways from that of the eastern Khanty, and second, specific features of the latter have been described in detail by Kulemzin (1976). The chronological framework of this work is the 18th to early 21st centuries. The geographical region extends from the Irtysh River’s mouth to the Gulf of Ob, and from the Urals to the right bank of the Ob in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra and Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug*.

Koipyng-nyait—shaman with a tambourine

In the Mansi and Khanty languages, koip means ‘tambourine’. Accordingly, the shamans who performed shamanic rituals with tambourines were called koipyng-nyait (‘a man with a tambourine’). Perhaps this was how

*This article mentions the settlements in the Berezovo (Yasunt, Shchekurya, Khoshlog, Khurumpaul, Lombovozh, Aneevo, Menkv-ya-paul, Tutleim) and Beloyarsky (Yuilsk) Districts of the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra, as well as the Shuryshkary (Tiltim, Vytvozhgort, Ovgort, Yamgort, Lorovy, Lokhpodgort) and Priuralsk (Zeleny Yar) Districts of the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug.

they differed from fortune tellers, who mainly used a saber, axe, knife, or sacred chest to communicate with spirits*.

Becoming a future shaman with a tambourine was not easy: “…not everyone becomes a shaman. Some people suddenly start to get sick. Puksikov got sick when he was about fifteen and was sick for about two years. Some people are sick up to three years. A man seems to be drunk; he walks on all fours, does not eat anything. Sergei ran away into the forest and could not be found for a long time. Finally, Mir susne khum [‘a man who watches over the world’, the youngest son of the supreme god Numi-Torum. – A.B. ] and oparishch [‘ancestors’ (Mansi) – A.B. ], pupykh [correctly pupyg ‘patron spirit’ (Mansi) – A.B. ] come to the man and tell him to start performing shaman’s rituals, beat the tambourine…” (from the diary of V.N. Chernetsov, 1931) (Istochniki…, 1987: 154); “When a man becomes a shaman, he gets sick. If he is to become koiupyng nyait , he is sick for a long time, does not recognize anyone, does not eat, does not drink, goes into the forest, and lives there nobody knows how. Then an oparishch , pupykh in the form of a totem, comes to him and tells him to make a tambourine and start performing shaman’s rituals” (Ibid.: 158).

Among various categories of shamans of the Ob Ugrians, Sokolova also mentioned koipyn nyait (‘shamans with a tambourine’) primarily among two groups, namely the Kazym and Synya Khanty. The main purpose of such shamans was to treat diseases (Sokolova, 2009: 644; 2016: 259–260, 492–494). On the Synya, shamans who perform rituals with tambourine are called kuipyn iki (‘a man with a tambourine’), or kuipyn sepan iki (‘man fortunetelling with a tambourine’) (Synskiye khanty, 2005: 175–176). According to informant E.G. Fedorova, from the upper Lozva River, the Mansi had four categories of shamans, including koipyn nyait or nyaityn oika (‘shaman with a tambourine’), and lylyng pupin nyait (‘shaman of a living (speaking) spirit’), who closely communicated with spirits, was the most powerful, and also had a tambourine. Only shamans with tambourines could cause harm (Fedorova, 1991: 166–167).

G.E. Soldatova distinguishes two categories among those engaged in shamanic activities: shamans proper and parashamans; they differ in their active or passive role in the ritual. The former perform actions: heal or cause harm, return hunting luck or take it away, etc. The latter focus on recognition: they predict, prophesy, or determine the cause of misfortune and the way to eliminate it. Ownership of a tambourine is typical of the first category (Soldatova, 2014: 78).

General information about shaman tambourines

S.I. Rudenko noted the uniformity of tambourines of the Ob Ugrians and Nenets people (1958: 296). I.N. Shukhov emphasized that the Kazym “tambourine and beater are somewhat different in shape and appearance from those of the Vakh, Obdorsk, and Samoyed shamans. The tambourine shape is almost perfectly round” (1916b: 31–32). According to Soldatova, organologically, all tambourines of the Synya Khanty belong to the same type. This has an oval shape, a U-shaped handle (solid or composite), a frame with small posts laid along it, and brackets with rings and bells, attached to the frame on the inside. No images are present on the tambourine; the beater is covered with fur (Synskiye khanty, 2005: 179).

A. Kannisto and V.N. Chernetsov recorded the Mansi names of tambourine parts—frame, membrane, resonators, handle, beater, etc. in great detail (Kannisto, 1958: 411; Istochniki…, 1987: 38). Among the Mansi, “a tambourine is made mainly of elk-skin, sometimes of deer-skin and even of dog-skin, stretched raw over a hoop two to three vershoks wide and up to an arshin or more in diameter; when dry, the raw skin tightly stretches over the hoop, then it is lightly sewn to the rim, to which rings, chains, bells, and various other sound-making objects are attached; from the inside, two sticks are inserted crosswise, with the help of which the tambourine is held in the hand…” (Gondatti, 1888: 12).

Rudenko wrote that the rim of tambourine was made of larch growing at a sanctuary. After cutting down a tree for this purpose, a silver coin was driven into its stump (1958: Fol. 281, 297). According to Chernetsov, among the Mansi, “the shaman makes a tambourine by himself. The frame is made of spruce growing in a sacred place near the family clan pupykh ” (Istochniki…, 1987: 156).

“On the upper Lozva and Sosva rivers, small posts [resonators – A.B. ] are fastened along the outer edge of the tambourine; on the Sosva, there are usually… 14 or 21 of them, but there can also be 13, 15, 17, or 19. These posts are called yur * ‘animal of the magic tambourine’. This is why a tambourine on the Sosva River is called ‘full drum occupied by seven yur -animals’” (Kannisto, 1958: 411).

A tambourine was also covered with skin of domestic deer (Shukhov, 1916b: 31), burbot (Shukhov, 1916a: 104;

-

*A Yur is a mythical beast often identified with a mammoth, etc., capable of causing landslides. On the Konda River, the yur was believed to be similar to a lizard. On the Northern Sosva River, it was represented as a fish; on the upper Lozva River, as a crayfish. The Voguls’ songs collected by B. Munkácsi mention a “living”, “crawling”, “toothy”, “winged”, “legged”, and “ironbodied” yur . One of the songs says that many winged yur animals fly to the sacred tree of the spirit; if the upper wind shakes the branches, many yur fly up (Mifologiya mansi, 2001: 67).

Baulo, 2017: 82), or bear (Sokolova, 2016: 558; Baulo, 2016b: 265). After the skin was dressed and before it was stretched onto the frame, a small round object with the size of a three- or five-kopeck coin was sometimes tied to the center of the membrane. This was done so that when the skin dried, there would remain some extra skin and the membrane would not burst. During the sacrifice, the membrane of the tambourine was sprinkled with the blood of the deer or horse. If repairs were needed, it was glued with cloth or fish skin.

The circumstances of manufacturing tambourines among the Synya Khanty in the late 20th century have been recorded. According to A.K. Kurtyamov from the village of Vytvozhgort, his father and uncle were shamans, and Afanasy himself was destined to become a shaman. To make a tambourine, one had to make a sacrifice at the sacred place in the basin of the Kempazh River— the area of residence of the Lyapin Mansi, who were the closest neighbors and often relatives of the Synya Khanty. During the ritual, they killed a white deer and took the skin with them. A spruce was cut down there. The stump of its trunk then lay for almost a year in a cult barn along with the dressed deerskin. Then, at the male sacred place in Vytvozhgort, during one day, Afanasy’s uncle made a tambourine from the brought stump of the tree and skin (the tambourine was supposed to be made by the father, but he was already seriously ill). During the work, those present were surprised by the fact that the hoop bent easily, without cracks. After the tambourine was made, another deer was sacrificed (Synskiye khanty, 2005: 162–163).

The author of this study has collected information on 44 tambourines (see Table ). The Table combines the data from collections by A. Ahlquist, A. Kannisto, I.N. Shukhov, V.N. Sokolova, I.N. Gemuev, A.M. Sagalaev, and A.V. Baulo, as well as exhibits from the collections of a number of Siberian museums, and presents some features of tambourines belonging to the northern Mansi (17 items) and Khanty (27 items) (Fig. 1). The shape of the tambourines is round (16 items) or oval (27 items). The handles are most often forked (26 items); 11 items have cross-shaped handles, of which eight are X-shaped; 5 handles are made in the form of the letter U; they are composite*. The handles of tambourines are usually abundantly wrapped with pieces of fabric: “The sorcerer and fortune teller are paid for their work. On the Upper Lozva, upon completion

Main features of shaman tambourines among the Northern Ob Ugrians

|

No. |

Location |

Owner |

Date |

Shape |

Handle |

Resonators |

Additional information |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Mansi |

|||||||

|

1 |

Rezimovo |

S. Pakin |

Late 19th century |

Round |

Forked |

14 |

Handle designates the spirit of the tambourine |

|

2 |

Vorsik-oyki sacred place |

T. Puzin |

1940–1950 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

14 |

– |

|

3 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

1940–1950 |

Oval |

ʺ |

14 |

Mask on the handle |

|

4 |

Yasunt |

I.K. Puzin |

1940–1950 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

21 |

Tambourine as a patron spirit, two shirts |

|

5 |

ʺ |

I. Nemdazin |

Late 19th century |

Round |

ʺ |

12 |

– |

|

6 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

First half of the 20th century |

ʺ |

ʺ |

16 |

– |

|

7 |

Shchekurya |

A.I. Sainakhov |

First quarter of the 20th century |

ʺ |

ʺ |

21 |

Tambourine as a patron spirit, five shirts. Resonator in the shape of a joint |

|

8 |

Saranpaul |

Mid 20th century |

ʺ |

ʺ |

14 |

– |

|

|

9 |

Lombovozh |

V. Albin |

1940–1950 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

Mask of the spirit of the tambourine on the beater |

|

|

10 |

ʺ |

P.E. Sheshkin |

First half of the 20th century |

Oval |

Y-shaped, composite |

16 |

Two masks of spirits carved on the handle |

|

11 |

Khanglasam-paul |

Puksikov |

Early 20th century |

Round |

Forked |

– |

|

|

12 |

Yasunt |

A. Tikhonov |

Early 20th century |

Oval |

ʺ |

– |

|

|

13 |

Upper reaches of the Northern Sosva River |

1960s |

ʺ |

14 |

– |

||

|

14 |

Shomy |

V.A. Adin |

Early 20th century |

ʺ |

Crossshaped |

21 |

Mask of a spirit carved on the handle |

|

15 |

Menkv-ya-paul |

Alkadyev |

Early 20th century |

ʺ |

ʺ |

15 |

Tambourine wrapped in a robe of brown color |

|

16 |

Khulimsunt |

T.I. Nomin |

1970s |

Round |

Crossshaped |

9 |

– |

|

17 |

Berezovsky District of the KhMAO– Yugra |

First quarter of the 20th century |

Oval |

Х-shaped |

14 |

– |

|

|

Khanty |

|||||||

|

18 |

Tutleim |

Novyukhov |

First half of the 20th century |

ʺ |

Forked |

14 |

“Dressed” in a large white shirt |

|

19 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

First quarter of the 20th century |

ʺ |

ʺ |

14 |

– |

|

20 |

ʺ |

ʺ |

First half of the 20th century |

ʺ |

Y-shaped, composite |

14 |

Repair of the membrane with pieces of fish skin |

|

21 |

Ishvary |

Togochev |

Early 20th century |

ʺ |

Х- shaped |

9 |

– |

|

22 |

Lorovy |

S.G. Eprin |

Early 20th century |

ʺ |

Arrow |

– |

|

|

23 |

Khanty-Muzhi |

N. Pastyrev |

Mid 20th century |

Round |

Forked |

27 |

– |

|

24 |

ʺ |

Early 20th century |

ʺ |

Х-shaped |

15 |

– |

|

|

25 |

Kazym River basin |

First third of the 20th century |

Oval |

ʺ |

27 |

– |

|

Table (end)

Patron spirits and guardian spirits of tambourines

The handle of tambourine is referred to as “ koipyng pupyg — the patron spirit of the magic tambourine. Its longer ends represent the legs of the patron spirit; the shorter ends, his head” (Kannisto, 1958: 411). The figure of the patron spirit is most clearly represented on the tambourine of the Khanty

Fig. 1 . Shamanic tambourines with forked ( a ), composite ( b ), cross-shaped ( c ), and X-shaped ( d ) handles. a – late 19th century, Mansi; b – second half of the 19th century, Khanty; c – early 20th century, Mansi; d – mid-20th century, Khanty.

man V. Ataman from the village of Zeleny Yar. The beater is tied to the sticks of the handle at the place where they intersect at the back. The upper part of the beater is covered with a piece of reindeer wool; the other end is egg-shaped. Thus, the crossed sticks and the beater form a semblance of an anthropomorphic figure wearing a hat and having a distinctively male feature—the genitals (Fig. 2).

“Among the lower Khanty, faces of seven spirits whom the shaman invoked during the shamanic ritual were sometimes carved on the …handle” (Rudenko, 1958: 296) (see also (Ivanov, 1970: 60)) (Fig. 3). “The handle is fork-shaped, with the image of a face in the fork. According to the shaman, this is St. Nicholas, who helps him with fortune-telling” (Shukhov, 1916b: 31–

-

32). Anthropomorphic masks on the handle have also been observed on the tambourines of the Lyapin Mansi (Gemuev, Sagalaev, 1986: 25; Gemuev, 1990: 102).

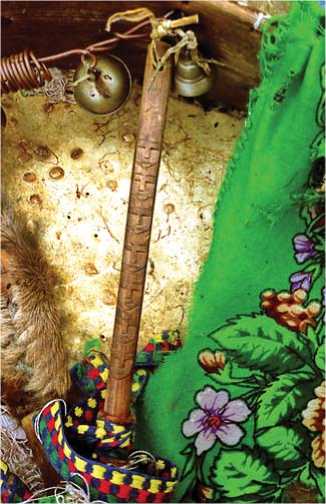

The tambourine’s beater has a narrow handle and wide striking surface covered with skin from a deer’s forehead. Some items have anthropomorphic masks carved on them, representing the patron spirit of the tambourine. Shukhov described a birch beater among the Kazym Khanty that “had an image of St. Nicholas on the handle” (1916b: 31– 32). The author of this study has observed masks on the handles of beaters among the Mansi Albins in the village of Lombovozh, the Khanty Artanzeevs in the village of Yamgort, and the Khanty Shiyanovs in the village of Lokhpodgort (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2 . The figure of the patron spirit of the tambourine, composed of a handle and beater. Sacred place of the Khanty in the Polui River basin.

Fig. 3 . Representations of seven spirits on the tambourine handle. The northern Khanty.

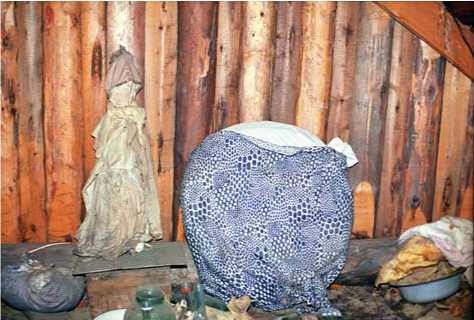

The Synya Khanty described a tradition of shaman patron spirits “living” inside the tambourine. The spirits formed a married couple and acted as shaman’s servants during the ritual. The first such tambourine was kept in the attic of a house in the village of Tiltim. It contained the figures of two spirits, husband and wife (Fig. 5, a ). Both were based on wooden anthropomorphic images. The male figurine was wearing several shirts and black coat buttoned with three buttons. A female figure wearing a white reindeer-fur coat was belted with a colorful kerchief. Under the coat, there were several shirts with coins of 5 kopecks from 1931, 10 kopecks from the 1930s, and a scrap of newspaper from 1942 inside. Traces of sacrificial blood were visible on some shirts. The second tambourine was kept in the village of Ovgort. It was wrapped in a man’s shirt with traces of the blood of a sacrificial deer. Figurines of a man ( kho ) wearing a white deerskin parka and a woman ( ne ) wearing a fur coat and scarves (Fig. 5, b ) were inside the tambourine. These were the spirits of the tambourine, husband and wife. The figures were made by the mother of the tambourine’s owner.

The Lyapin Mansi have another tradition: tambourines are “guarded” by koipyng-pupygs (‘tambourine spirits’), acting as protectors*. These are placed at the back wall

Fig. 4 . Beater with a mask of the patron spirit. The northern Khanty.

of the attic, next to the tambourine (Fig. 6). The figure of koiping-pupyg usually consists of seven votive arrows wrapped in cloth, with several shirts and robes placed over it. The head is represented by a cone-shaped hat

Fig. 6 . Koipyng-pupyg and shaman tambourine—family patron spirit. The Lyapin Mansi.

b

Fig. 5 . Tambourines with figures of patron spirits. The Synya Khanty.

made of cloth; the plume is made of seven tassels. The length of the figures is 50–75 cm.

Shamanic rituals with tambourine

Unfortunately, there are no detailed descriptions of rites with the tambourine, and not so many fragmentary reports from eyewitnesses. The most complete description of the shamanic rite was left by N.L. Gondatti: “During the performance, the shamans… have… in their hands a tambourine, which they occasionally strike with a special stick covered with skin of some animal… all rattles make loud noise with strong and fast movements made by the shamans during the invocation of gods. The tambourine itself, when struck, makes a distinct sharp sound, especially if it is held over the fire for some time beforehand; these sounds are pleasing to the gods… Most often, Mir susne khum is invoked… for his invocation, people most often use nights, when he makes his rounds around the earth; to do this, the fire is extinguished in the dwelling where the fortune-telling takes place; the shaman beats the tambourine several times and then everything falls silent and a deathly silence ensues, in the midst of which the sound of horses’ hooves can apparently be clearly heard, ending with a crack indicating the god’s entrance into the dwelling; after which everything stops and the shaman, often stretched out on the floor, begins to report what the god has told him… <…> Once, during a smallpox outbreak, one Ostyak’s entire family died, and finally he also fell ill. He called for the shaman, who began to beat the tambourine, whisper something to himself, and finally started to dance; he spun and whirled all night, and then announced that the Ostyak would die…” (1888: 11–16).

V.V. Bartenev, a revolutionary exiled to Obdorsk, was present at a shamanic session: “The shaman comes with an assistant who repeats his words, and with a penzyar (a tambourine made of reindeer skin, which is struck with a beater). The divination takes place in the following manner. After entering the chum, the shaman sits down next to his assistant, and all those present sit down as well. Then the tambourine is heated so that the skin stretches tighter: the sound becomes louder. The shaman begins to beat the tambourine, at first quietly and once in a while, then louder and more often, finally, with all his might. At times the beat weakens, and then these strange sounds intensify again, dully spreading across the tundra. At the same time, the shaman, and those present following him, shout in a drawn-out voice: ‘ko-o-o-o! ko-o-o-o!’ This is done to invoke the spirits. When the spirits flock to the shaman, he begins to question them and passes the answers on to those present” (1896: 87–88).

Feldsher L. Korikov described his trip to the village of Khurumpaul in December 1898 to see a sick Vogul. A small chest with a tambourine lying on it was in the yurt above the bunks. The sick man refused help and ordered a shaman to be called. A gray-haired old man entered, took the tambourine from the shelf, put on expensive brocade robe, and began healing. A sharp blow on the tambourine was heard; then more blows followed “accompanied by a trembling old man’s voice”. Finally, the sound of the tambourine died away. “Suddenly, a heavy sigh broke the grave silence. <…> At last, a quiet, distant, but impressive voice was heard. It was the shaman speaking. He finished communicating with Torm* and now announced the sacrifice required by the god” (Korikov, 2003: 59–62).

According to A. Kannisto, “on the Upper Lozva, the shaman uses a tambourine if someone falls ill. He sits in the room in front of the fireplace with burning fire, or in the chum near the hearth and warms the tambourine, singing a magic song ( pupyg kaisov )… Singing of the kai sov is accompanied by eating fly agarics…” (Kannisto, 1958: 432–433). One of the invocatory songs recorded by Kannisto also mentions actions with tambourine:

A tambourine filled with seven yurs , A tambourine filled with six yurs , They tune (rock).

Appointed by the spiritual patron for the dark night, Appointed by the Torum for the dark night They tune (rock).

A tambourine filled with seven inserted (heads) yurs

I hear, they tune,

A tambourine filled with six inserted (heads) yurs

I hear, they tune

(Mansiyskaya… poeziya, 2017: 35).

V.N. Chernetsov described a ritual associated with the Mansi idea of a person’s second soul, urt : “A man died. If someone he knew is in an open place or outside the house that night or the next night, the urt of the deceased attaches itself to that person in order to take him away with it. The person to whom the urt attached itself then feels unwell or heavy. In that case, a shaman is called… The shaman then takes the soul that attached itself to the living person. The shaman strikes a tambourine, rubs the tambourine against the person to whom the soul has attached itself, and then says: ‘Well, now it has shaken itself out’” (1959: 131).

M.N. Gogoleva, a resident of the village of Aneevo, said: “One shaman in the dark at night in his house hits arrowheads against each other, and another shaman beats a tambourine, and all in tune. And then he speaks coherently, the one who beats the tambourine; he is the main one. And then he says: don’t let the child out on the street or what to feed him” (Baulo, 2017: 82). Recalling how he performed a shamanic rite, informant P.F. Merov assumed a distinctive posture: a tambourine in his left hand skin side down, face raised up, gaze to the left not looking at the tambourine (Baulo, 2016b: 265).

The tambourine after the shaman’s death

The fate of a tambourine after the death of its owner was not clear. Rudenko wrote about the northern Khanty that “upon the death of fortune tellers, their tambourines were placed near the grave, and tambourines of shamans were hung on a special tree at the sanctuary. Tambourines were passed down by inheritance” (1958: 297). Among the Kazym Khanty, “upon the death of a shaman, the tambourine is pierced and kept in a barn at the sacrificial site” (Shukhov, 1916b: 32). Informant A.D. Tarlin said that when his grandfather, a shaman, died, “they heated the tambourine strongly over a fire and hit it. The skin burst. Then they took everything to the forest, and left it for the gods. If you do not tear it up and take it to the forest, there will be misfortunes in the family” (FMA, 1998, village of Yuilsk). After the death of A. Pyrysev from the village of Yamgort, his tambourine was buried in the forest along with other sacred objects (Synskiye khanty, 2005: 176). Among the Sosva Mansi, “when a tambourine breaks through, the skin is hung on a tree in the place where it broke” (Istochniki…, 1987: 156). Their informants also mentioned that the shaman is buried separately, and “the tambourine is then chopped into pieces… and everything is thrown there, into the grave” (Snigirev, 2013: 524).

Tambourines of the northern Ob Ugrians could have a different fate: after the death of a shaman, these received the status of a family patron spirit whose anthropomorphic appearance was emphasized by “dressing” the tambourine in men’s shirts. The author of this study first encountered this practice in 1999 in the village of Shchekurya among the Mansi. Here, in the attic of the house of A.P. Sainakhov, the tambourine of his grandfather A.I. Sainakhov (repressed in 1936) has survived, “dressed” in five specially sewn shirts with long sleeves (Fig. 6), and the owner was not even aware that a shaman tambourine was inside the clothes (Baulo, 2013: 186). In the attic of the house of I. Puzin in the village of Yasunt, his grandfather’s tambourine was also kept, “dressed” in two shirts, and was revered as a family patron spirit (Fig. 7, a ). In the village of Menkv-ya-paul, an old shaman tambourine of the Alkadyevs was in the attic, wrapped in a brown man’s robe (Gemuev, Baulo, 1999: 101).

A similar tradition of transforming a tambourine that has fallen out of use into a family patron spirit has also been recorded among the Khanty. The Novyukhovs’ tambourine in the village of Tutleim was “dressed” in a

b

а

Fig. 7 . Shamanic tambourines that became family patron spirits of the Mansi Puzins ( a ) and the Khanty Longortovs ( b ).

large white shirt. Judging by the coins of 1874, 1931, and 1946, preserved in pieces of cloth, it was used in the first half of the 20th century, after which it became a part of the family household gods (Baulo, 2016a: 282, fig. 451). Among the Synya Khanty in the village of Vytvozhgort, a white men’s shirt was put on the old tambourine of the Kurtyamovs, and a shirt made of brown woolen cloth with short sleeves was put on the tambourine of the Longortovs in the village of Tiltim; its lower part was tied with a cord—the figure was belted (Fig. 7, b ) (Ibid.: 288).

Conclusions

The topic of shamanism is one of the most neglected roday, largely because the older generation still remembers the years of persecution that the adherents of traditional cults had to endure. Nevertheless, judging by the published sources and stories of informants, in the second half of the 20th century, shamans continued to perform their functions in a number of villages inhabited by the northern Khanty and Mansi. These functions were primarily limited to fortune telling and healing; more rarely, to leading rituals at sanctuaries. The word “shamanism” has been simplified to a certain extent. Today, turning to a patron spirit for a person means “to shamanize”, sacred places are colloquially called “shamanic”, and people who perform some kind of rite are often considered to be shamans.

Special clothing of shamans and fortune tellers among the northern Ob Ugrians in the 20th to early 21st centuries has not been observed; caftans, robes, and hats were multifunctional. They may rather be called ritualistic— for shamanic rites, bear festivals, and dressing the patron spirits. Almost the only attribute of a shaman is the tambourine.

Notably, the total number of tambourines described by predecessors and encountered the author’s field works is not so large, amounting to 60–70 items. For example, the author of this article knows over 400 attributes of the cult of Mir-susne-khum —sacrificial covers, warrior belts, and helmets with the image of a galloping horseman. Modern data (20th to early 21st centuries) show the predominance of the attributes of the Heavenly Horseman in the religious and ritualistic realm over those of shamans and fortune tellers (even if we add cold weaponry used in fortune telling to tambourines). In fact, there are very few descriptions of shamanic rites with a tambourine.

The small number of tambourines and descriptions of rites with them tend to confirm the point of view on the underdeveloped shamanism among the northern Ob Ugrians, although the shamanic practices of these groups produced some original features.

-

1. Since the tambourine was understood as the shaman’s riding deer, some tambourines had small resonating posts made in the form of deer joints.

-

2. Figures of spirits of the tambourine, usually husband and wife, are made together with tambourines. Masks on the handle or beater also represent spirits. Among the Lyapin Mansi, tambourines are accompanied by the figures of koipyng-pupygs , their guards.

-

3. During animal sacrifice in the course of a shamanic rite, the membrane of the tambourine, as well as the clothes of the figures of his spirits, were sprinkled with deer or horse blood.

-

4. There are rare examples of using a tambourine after its owner’s death as a family patron spirit, which is confirmed by the clothing observed on it.

-

5. During shamanic rites and fortune telling, tambourines could be replaced by musical instruments ( sankvyltap , nars-yukh ) or sabers.

In the 20th to early 21st centuries, tambourines were common in the following main local areas: the Lyapin River basin for the Mansi, and the Synya River basin for the Khanty. The sources of these rivers are located close to each other, and in the 18th–19th centuries this territory was a contact zone of the Ob Ugrians and Nenets people. In general, we should speak about the influence of the Nenets traditions of making and using tambourines on the northern Khanty and Mansi.