Social Representations in the Cultural Field: A Sociological Approach to the Power Disputes in the Appropriation and Social Legitimation of Cultural Goods in Mariana (Minas Gerais, Brazil)

Автор: Annelizi Fermino, Thiago Duarte Pimentel

Журнал: Современные проблемы сервиса и туризма @spst

Рубрика: Региональные проблемы развития туристского сервиса

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.18, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

This article investigates the power struggles inherent in the social representations of cultural heritage within the context of Mariana, Minas Gerais, focusing on their appropriation and legitimation processes. Grounded in Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of fields and Serge Moscovici’s Social Representations Theory (SRT), the study examines how competing representations among heritage preservation agents operate within a field of forces. Findings reveal that the institutional (official) perspective – which dictates heritage listing criteria – is predominantly shaped by the hegemonic representations dominating this subfield. The research adopts a multiple case study approach, analyzing agents engaged in Mariana’s heritage preservation through: a) Questionnaires and semi-structured interviews; b) Systematic non-participant observation; c) Documentary analysis (newspaper archives, municipal records). Key outcomes include: 1) The contextual dynamics of social representation (SR) production; 2) The typology of representations and their hierarchical positioning among agents; 3) The contestation and legitimization of SRs within the subfield. The study demonstrates that a representation’s dominance correlates with its degree of social dissemination and institutional validation. The most socially legitimized SRs emerge as "victors" in the ideological struggle to define heritage. Consequently, the research underscores how economic and cultural capital underpin both the construction of heritage representations and their legitimation mechanisms.

Cultural heritage, social representations, field and legitimation

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/140309806

IDR: 140309806 | УДК: 338.48 | DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15531307

Текст научной статьи Social Representations in the Cultural Field: A Sociological Approach to the Power Disputes in the Appropriation and Social Legitimation of Cultural Goods in Mariana (Minas Gerais, Brazil)

To view a copy of this license, visit

Society is experienced in various ways by each social actor. This heterogeneity of social life is linked to the plurality of groups that, unequally positioned in social space, engage in diverse dynamics of information appropriation, circulation, and acquisition. These dynamics manifest in distinct worldviews and forms of interaction observable in objects and social relations. Although cultural heritage is a common good of public interest, it is no exception. Living with heritage assets is shaped by varied identities, knowledge, and uses shared among groups. In this context, while some individuals feel represented by these assets, others perceive themselves as those who do not value or engage with them. Given this process, in which existing inequality among groups shapes varied modes of experience, we aim to contextualize the diversity of conceptions and interactions that constitute each social representation of cultural heritage.

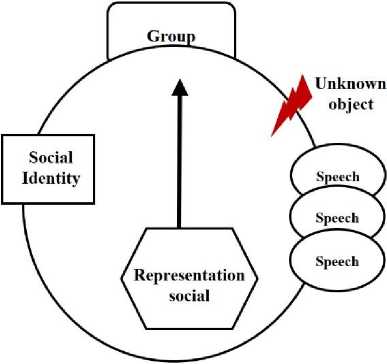

From the perspective of the Theory of Social Representations (TSR), this context offers a chance to comprehend the various forms of perception and value attribution concerning heritage assets. As elaborated by Serge Moscovici (1961), social representation can be understood as a system of classification and expression where objects are assigned and categorized based on a process of interpreting reality (Reis; Bellini, 2011). This form of knowledge (social representation) involves assimilating the unknown, leading to its integration within worldviews and positioning. Through social representations, one can identify how social agents manage conflicts, build relationships, and form opinions.

In a context of diverse identifications and social and cultural demands, we consider that the influence exerted by one’s position in social space lends greater credibility to certain social representations over others. This article aims to understand how various social representations of cultural heritage are positioned within social space and how a specific social representation can become hegemonic at the expense of other representations. To develop this approach, we draw on Pierre Bourdieu's concept of field to analyse the diversity of representations within a hierarchical social space. Through the lens of TSR, we identify these representations, while the concept of field helps us comprehend how different groups produce social representations of cultural heritage.

The research was empirically conducted through a multiple case study of all the main social agents of the cultural heritage subfield in Mariana (MG). The historic city was chosen as the locus of the study because it was the first capital of the state of Minas Gerais and has a wide range of recognized and protected heritage assets. It stands out in the preservation ranking of the ICMS Cultural Heritage.

The research, of a mixed quantitative-qualitative nature, focused on identifying and analysing the SRs of the following groups: municipal administration, residents, tourism agents, and the Municipal Council of Cultural Heritage (COMPAT). The criterion for selecting and sampling these groups was their involvement in activities related to heritage preservation. Data collection involved the use of questionnaires, interviews, simple observation, and research in newspaper databases and the municipality's official sites. Data analysis was supported by the content analysis technique, allowing for the identification of the axes and themes that constitute these SRs.

The main results show 4 types of SR, type "a" common to the official spokespersons of the municipal administration, type "b" which conceives of heritage from life stories, type "c" in which critical stance prevails on how preservation is carried out and its real scope, and type "d" which emphasizes the economic potential of cultural tourism. We also found that the best positioned agents in this space are those who are traditional residents involved with culture and possess historical knowledge about these assets. Such results lead us to infer that the disputes occurring between the SRs of type "a" and "c", therefore, take place in the institutional sphere between participants from the munici- pal administration and COMPAT and that in this context the legitimacy of the SR is attributed to the agents who value culture the most.

This article is organized into the following parts: the theoretical approach, where we explain the main concepts of TSR and field theory and how they are articulated; the description of the methodology, where we detail the means by which we conducted the research; the data analyses, which are grouped into general characteristics of the production context, types of SR identified, positions occupied in the subfield, and disputes and legitimation involved; and finally, we present considerations about the results of the analysis.

2. The Theory of Social Representations: main approaches and concepts

The Social Representation Theory was first outlined by social psychologist Serge Moscovici in his publication La Psychanalyse, son image et son public (1961). In this work, he analyses the social representation of psychoanalysis. By examining how non-scientific knowledge is produced, he formulated social representations as a classificatory and denotative system that organizes everyday experiences by framing them within a worldview.

The concept of social representation (SR) builds upon and extends Durkheim's idea of collective representation. According to Moscovici, Durkheim's collective representations cannot adequately account for the diverse ways of organizing thought found in everyday interactions, as they pertain to broader forms of organization, such as science, ideology, and myth—where collective functioning subordinates the variable elements to a stable social and/or institutional structure. Recognizing the variety of ways to understand the same object, Moscovici posits that social sharing emerges from collectivities that, by virtue of belonging to a particular social context (shared references and information sources), develop specific representations. Thus, SR serves as an analytical category rooted in the bilaterality of its configuration process (psychosocial), where various forms of knowledge about the same object are linked to the cognitive dimension, through which this knowledge is processed, and its social sharing among groups.

TSR is a concept regarding rationality and the intellectual aspect of common sense. From this perspective, cognitive phenomena are always empirical, as they can be identified in language, discourse, documents, practices, and other material forms. The construction of representations occurs "through observations, analyses of those observations, and notions and languages that are appropriated from various sources, in both the sciences and philosophies, drawing conclusions that impose themselves." (Moscovici, 1978, p. 45). The objects of these representations are situated within active and dynamic contexts emerging from the flow of information, which exist for each social group or subject based on the means available for their understanding. These representations result from the combinatory capacity of fragmented elements of diverse types of knowledge acquired by social subjects when framing objects (events, concepts, people) in their daily lives. Representations function by providing groups with notions, observations, opinions, and other elements related to behaviour; they instill meaning into behaviour that, due to its shared nature, impacts social relations. Another characteristic of representation is its ability to modify elements of the environment in which it exists, as its functioning influences how the world is perceived or ought to be understood. The dynamic of familiarizing what is strange – that which lies outside the typical universe of a group – alters the universe while maintaining its status as the known universe (Moscovici, 1978). The conditions of production and the manner in which SRs are integrated into relationships and operate in social reality characterize this knowledge as practical.

The first step involves identifying the presence of nuclear and peripheral elements in the SR structures as outlined by Abric (2001). This framework demonstrates how every representation is organized around central cores, which are responsible for structuring and directing individuals' actions in relation to the represented object, and peripheral elements that are conditional, practical, and essential for adapting the representations to everyday experiences.

A second set refers to the development of a methodological procedure capable of accessing the "totality of phenomena" involving the SR, as noted by Jodelet (Galli, 2014, p. 13). By integrating procedures from ethnography, history, social psychology, and sociology to identify SRs, Jodelet connected communication, cultural models of behaviour, and the real and symbolic practices surrounding the operation of SRs (Galli, 2014).

These are the main contributions to TSR. The approach to heritage representations was based on Moscovici's theoretical framework, which helps us understand the characteristics, functions, and essential concepts of a social representation. However, it is worth noting that we integrated Jodelet's categories of analysis to identify the representations.

2.1 Central elements of TSR: objectification, anchoring and themata

The elaboration of a social representation is part of the cognitive functioning organization of the social group in response to coexistence demands. Two processes are fundamental to the elaboration of a social representation: objectification and anchoring. In the first, assimilation and naturalization of the object occur, as objectification organizes all the meanings and information we acquire about an object. Thus, ideas are no longer seen as products of intellectual activity, but as reflections of external realities. The perceived is replaced by the known, reducing the gap between the knowledge produced by science and reality (Moscovici, 1978). Anchoring, on the other hand, corresponds to the process of social rooting, where the notion developed through objectification is classified according to the values and interests of the groups.

Each social agent maintains a stock of elements and meanings acquired through communication. Through the process of objectification, links are established between this stock and the objects present in reality. This connection is made through a selection that reflects a physiological need to reduce the continuous flow of elements associated with the object. The purpose of this selection is to create an orientation amid the variety of information. Moscovici explains that to objectify is "to reabsorb an excess of meanings by materializing them (thus adopting a certain distance from them); it is also to transplant to the level of observation what was only inference or symbol" (Moscovici, 1978, p.111). Objectification is an image-forming process in which the abstract is transformed into something concrete. It operates by making a conceptual scheme tangible, thereby allowing an image to have a material counterpart.

Objectification occurs through three operations: the first is the perception of the object and a consequent decontextualization of the original information; the second is the formation of a figurative nucleus, which consists of the figurative structuring of a concept;

and finally, its naturalization occurs, a procedure in which a meaning loses its intellectual exteriority and begins to directly designate a certain reality (Spink, 1993). These stages can be observed in Fig. 1.

Selecting the element and decontextualizing it from its original context

Forming a figurative core

Naturalization of the figurative core elements

Fig. 1 – Stages of objectificatio n1

The information, which is not equally accessible to everyone, is unevenly distributed and appropriated by different social groups, resulting in a fragmented or distorted understanding of the original information. The formation of a figurative core involves the psychological process of establishing coherence between the object and the referential framework of the social subject. From this figurative core, the naturalization of conceptual schemes emerges, a process in which concepts are assimilated according to the subjects' understanding, conveying the impression that discussions about the world are not merely intellectual constructs but are part of reality. Abric (2001) argues that all reality is represented since the process of objectification creates the sensation of reality, and thus, there is no objective reality a priori.

The anchoring process continues the social insertion of this object through its classification, ensuring that each representational reality is socially configured. The object is positioned within a scale of interests and values of social groups, taking root in the established relationships (Moscovici, 1978). As a result, the developed notion transforms into an instrument that society can use as a guide for perceptions and judgments of reality. This social incorporation of the representation's contents is achieved through a network of shared meanings in the social sphere.

Social representation is connected to the position (social place) individuals hold in society and to the situation (state) they find themselves in, thereby incorporating the social aspect. The social dimension of representations is formed through the act of communicating (interacting), which is mediated by cultural background and the specific forms of understanding that each individual carries with them—codes, values, ideologies, and symbols (Sêga, 2000). This relationship between cognition and social attributes means that cognitive impasses extend from life in society, while social attributes emerge as products of cognitive constructions and perceptions of reality. Every social representation is a process through which the connection between the world and objects is established. The Fig. 2 below illustrates this process of elaboration.

Fig. 2 – Schematic representation of the sociogenesis of social representation s2

This cycle represents the social dynamic involved in forming a new representation. When a group encounters an unfamiliar event or object, it initially responds by objectifying the abstract, meaning it selects the abstract elements or ideas that emerge in its context and organizes them into a concrete image. This process enables the group to access and understand the object, thus transforming it into part of their reality. This first stage concludes with the anchoring process, which involves taking this figure and integrating it into the subject's social experience. During this contextualization, the image is classified and incorporated into the group's collective knowledge.

Another issue Moscovici considers is the relationship between social representations (SRs) and structure. SRs are formed from preexisting thoughts associated with beliefs, values, traditions, and images, which in turn are historically structured in society. Thus, Moscovici (2004) argued that social representation as a system of prescription is not limited to its content. Although representations function in everyday life, they also store preconceived and pre-ordained (structured) situations that are communicated across generations and classes.

The concept of themata, on the other hand, was further developed to analyze representations in which objects are based on systems and collections of languages, whose meaning presents linguistic traces, sets of discourses, and other indications of historical backgrounds3. Therefore, the discourses, beliefs, and representations come from other discourses and other social representations and are derived from something already preexisting, so there are themes that endure as image-concept or as primary conceptions in the collective memory (Moscovici, 2004). The themata refers to the process of thematiza-tion of the discourse, that is, the stabilization of a meaning (theme) as a major reference and capable of inducing images or ways of being. Moscovici points out that this circumstance may be an explanation for the fact that some SRs become dominant while others are circumscribed to the micro-social domain of groups. However, despite having been studied by different researchers (to name a few) the concept of themata – as a form of indicator of stabilization of certain representations in the long term, at the macro-social level - is still recent and lacks methodological developments (cite authors), as well as empirical studies for further verification.

This study attempts to fill this gap by using Pierre Bourdieu's concept of field to provide a framework regarding the hierarchization and legitimization of SRs among social groups upwardly and over time. In the next section, we will address Bourdieu's concept of field and some of its analytical possibilities with TSR to further explore such a relationship.

2.2 . The concept of social field and a sociological approach to SR

Over the last three decades, researchers have articulated TSR and field theory in their analyses. These approaches address the dual challenge proposed by both Moscovici and Bourdieu: “on the one hand, to oppose the determinist objectivisms (which were already fashionable in the 1960s and 1970s in the social sciences); and, corollarily, to oppose the interactionisms without measure, in which relativisms and subjectivisms of various shades end up annulling the role of the instances of the social (society, institutions, groups, classes)."(Abdalla; Domingos-Sobri-nho; Campos, 2018 – emphasis in original).

These combinatorial studies are motivated by conceptual approximation. Both authors proposed overcoming the dichotomy of subjectivity and objectivity in the individualsociety relationship and developed a theory concerned with the symbolic dimension in the construction of social reality (Lima; Campos, 2015). Other approximations can be drawn. Moscovici and Bourdieu are contemporaries who lived and worked in Paris and defended the "autonomy and distinctiveness of their respective disciplines" (Jesuíno, 2018, p.45), which indicates that the dialogue between these two theories is possible and interesting.

In our analysis, we begin with the understanding that representations of heritage, as well as other cultural objects, are organized within a context of power dynamics and social hierarchy that influences the processes of legitimation and other aspects of social sharing. This impact of structure (power and hierarchy) on social representations can be understood through the relational logic that Bourdieu attributes to the concept of structure. According to the author, structure represents an articulation between objective structures (independent of agents) and social structures that emerge from social genesis (practices, behaviours, knowledge, and perceptions), allowing for a social space that encompasses agents from their respective perspectives. In this regard, representations are constructed from a specific viewpoint determined by the objective position that agents occupy within the social space (Bourdieu, 1996).

The concept of the social field is the category we use to frame the SRs concerning cultural heritage within the social space, thereby broadening our understanding of its social context of production. Fields are spaces of objective relations governed by their own logic, formulated by the specific needs that each field presents, and they operate in a relatively autonomous manner within the social cosmos. Their structure is defined by the state of power relations among agents (players), which configures itself as a field of force, constraining the agents that compose it to act according to their positions. This structure provides a matrix of perceptions, appreciations, and actions that preserves the characteristics and specific needs of the field. Bourdieu states that: "In fact, and cautiously, we can compare the field to a game (jeu) although, unlike the latter, the field is not the product of a deliberate act of creation, and follows rules or, better, regularities that are neither explicit nor codified. So we have what is at stake (en-jeux), which for the most part is the product of competition between players" (Bourdieu; Wac-quant, 2005, p. 151 – emphasis not original).

Based on the laws and distinct properties of a field, the dispute over specific objects and interests is organized by the agents (pretenders x dominants). The agents are prepared for the dispute to the extent that they are socially informed (habitus)—this comprises the ingrained practical sense of how to act in various situations, enabling the recognition of the laws governing this game. Since "the habitus makes it possible to establish an intelligible and necessary relationship between certain practices and a situation, whose meaning is produced by it on the basis of categories of perception and appreciation; these in turn are produced by an objectively observable condition" (Bourdieu, 2007, p.96). The functioning of each microcosm corresponds to the dynamics among agents to exert the forces of reproduction, domination, and transformation, as belonging to a field means being capable of producing some effect within it (Bourdieu; Wacquant, 2005). Each field is constituted by objects in dispute and specific interests, resulting in a variety of field types, which operate according to these interests.

Objective structures exert a shaping influence on agents, as they are integrated by the agents to form an acquired system of preferences (Bourdieu, 1996). Within this system, the position held – configured through objective relations and determined by the distribution of capitals – establishes what is dominant. However, the authority (power) provided by the occupied position is potential, as the accumulation of capitals according to the field's rules can lead to changes in power and position. The strategies that occupants employ, whether consciously or unconsciously, to maintain or enhance their standings characterize the field as a realm of potential and active forces (disputes). These strategies depend on the positions of the agents within the field, as their perception is shaped by the socially informed objective structures (Bourdieu; Wacquant, 2005).

From the perspective of the social field, society is structured in a hierarchical system of positions determined by the economic, cultural, and symbolic relations maintained by agents (capitals). The valorization of a specific capital is directly related to its particular field, as it relies on that field's limits and rules. The types of capitals are: economic – which corresponds to the accumulation of goods and wealth, such as income and material possessions that the agent has; social – referring to the social effects of relationships, that is, the ability to mobilize and obtain resources, favours, and reciprocity from their group and the position they occupy in the social hierarchy; cultural – connected to learning and education, it pertains to success in schooling, acquired knowledge, recognition through diplomas, and cultural goods the agent possesses, such as books and types of leisure activities (theatre, cinema, arts, soccer, etc.); symbolic -expressing the recognition of authority, prestige, and status. For Bourdieu, symbolic capital represents a transformation of objective reality – that is, the goods, titles, and schooling possessed – through perception and appreciation (Bourdieu, 1986).

Capitals are related in that they are capacities for appropriating the instruments of material and cultural production and for symbolically appropriating those instruments. In each specific field, capitals are recognized according to its rules of operation, which prioritize the status of a given capital over others. Capitals are also responsible for configuring positions in the social hierarchy.

The ordering among the positions is related to the specific properties that constitute each field. This means that the attribution of value to capitals can differ between fields. Therefore, another characteristic of the field is the struggle by agents to preserve or subvert the legitimation of a group's objects of interest. Through these disputes over the distribution and valorization of capital, the dynamics of structure reproduction and resistance to domination are articulated (Bourdieu, 1983).

Reading the social context of SR production through the field category allows for the inclusion of relational effects in the representations, which arise from interactions and exist independently of consciousness. This is essential since the concept of group presented by TSR does not reflect evidence of conflict. While the SR is developed within the symbolic context of its associated group, "the group's interest in dominating the object is not directly and explicitly inscribed in a context of conflict with other groups; there is no reference to the notion of struggles or forces" (Lima; Campos, 2015, p.73).

By conceptualizing SR concerning cultural heritage as an object within a field, we recognize that producers are influenced by objective structures that shape their preferences, and that their practices serve as a structuring force within this field. We believe the SR of an object (symbolic force) exists within a network of forces entangled in a complex relationship of intra- and inter-group influences, as noted by Lima and Campos (2015), delineating the positions of each group and defining conflicts. Thus, in examining the subfield of cultural heritage, we identify conflicts, legitimations, and other characteristics of the social space where these social representations are developed.

3. Methodology

The research is of a mixed nature (quantitative and qualitative) and consists of a comparative study of multiple social groups and their social representations (SR) related to cultural heritage in Mariana. This study is conducted in three phases: (1) documentary research using secondary data, (2) a preliminary quantitative survey of social groups based on their relationship with the studied object, and (3) a qualitative study of the specific groups identified and their SR.

In the first phase – documentary research – efforts were made to gather documents related to the studied area, the city of Mariana (MG), to provide a general background in which the groups and research object are situated, along with both official and unofficial data concerning its cultural heritage. The historic city of Mariana, located in the state of Minas Gerais, has a heritage spanning 322 years and boasts a considerable collection of preserved cultural assets. During this phase, we utilized secondary sources, including the database of the Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN), the State Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage of Minas Gerais (IEPHA), Mariana City Hall, and the Mariana City Council websites to collect information about the city, as well as newspaper reports to identify existing conflicts and disputes related to its heritage.

Additionally, we utilized systematic nonparticipant observation, recording data in a field diary. The purpose was to gather preliminary data regarding daily interactions with heritage assets, usage patterns, and potential conflicts, which informed the creation of the questionnaire and the selection of appropriate locations for its implementation. The observation occurred in June 2016 and involved circulating, observing, and engaging with passersby and workers in the historic centre, as well as collecting materials related to heritage promotion available in the area.

The second stage – a preliminary quantitative survey of social groups – was conducted using a questionnaire to collect information about the population's involvement with the heritage, applied in August 2016. The questionnaire was of a mixed type, and the sampling method used was non-probabilistic (based on accessibility or convenience). The sample consisted of 100 participants, including 36 males aged 27 to 68 and 64 females aged 18 to 75. The squares Claúdio Manoel and Gomes Freire, located in the historic centre, were selected as the locations to approach passers-by. The questions aimed to gather data on interaction methods, heritage identification, and opinions regarding the heritage and its preservation. With the data collected in this phase, it was possible to identify and characterize four social groups involved with the cultural heritage object in Mariana: (1) Public Administration, (2) Residents, (3) Tourism agents, and (4) Municipal Council of Cultural Heritage – COMPAT.

From that point onward, we moved to the third stage of the research – qualitative analysis – conducted through semi-structured interviews held in October 2016, featuring 15 participants. The selection of interviewees involved choosing representatives from the municipal administration who hold positions of responsibility for cultural heritage, members of COMPAT, and individuals suggested by the interviewees themselves as notable or significant for the interviews. The semi-structured framework was developed based on the theoretical and methodological model proposed by Jodelet (1993), focusing on identifying Who knows and the source of their knowledge, What they know and how they acquired it, and What they are knowledgeable about and the implications of that knowledge. According to the author, these questions are essential for identifying a social representation.

Following data collection, the treatment of the information from the questionnaire involved developing an interpretative criterion where we organized and systematized the proportion of monuments known to the population. We identified the frequency and forms of interaction with the heritage, the extent of information disclosure and access to the heritage, opinions about the heritage, and what respondents deemed important to preserve. For the interviews, we employed thematic content analysis (Bardin, 1970), structured around the aforementioned theoretical categories derived from Jodelet (1993): (1) Who speaks, (2) What is said, (3) To whom, (4) Where, (5) When, and (6) About what. In this step, we also identified the interviewees with the letters A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, L, M, N, and O to maintain their anonymity and associate each type of SR with the respective agents' positions within the Cultural Heritage subfield.

Based on the SR analysis categories – specifically conditions of production and forms of circulation, processes of elaboration, states of representation, and the epistemological status outlined by Jodelet – we identify the social representations and then proceed to analyze the aforementioned subcategories: (1) Who says, (2) What is said, (3) To whom, (4) Where, (5) When, and (6) About what. These categories facilitate an analysis of social representations that conceptualizes them as an organization of mental content through cognitive processes that emerge within the contexts and conditions in which they are socially produced and communicated.

To understand social representation within the social logic, as a product of agents situated in a social space of contested interests, power, and social hierarchization, we utilize the concept of field as a category to heuristically comprehend the structure of the social space where relations and conceptions regarding cultural heritage take place. By identifying the significant capitals within the field, we socially position the agents that produce the identified social representations and illustrate the dynamics of social legitimation involved.

From these categories, we conduct an analysis and interpretation of the data regarding the proposed problem, which involves the existence of various understandings of cultural heritage and the hierarchization implied among these social representations.

4. Analysis4.1 Locus and Object of study 4.1.1 General characteristics of the context of SR in Mariana

The city of Mariana plays a significant role in the historical formation of the state of Minas Gerais. Located in the central region of Minas Gerais, this historical municipality celebrated its 322nd anniversary on July 16, 2018, and developed around the earliest gold discoveries. Mariana served as the first capital of Minas Gerais and emerged as an important religious centre, hosting the inaugural seat of the Minas bishopric in 1745. Its significance in Brazilian history, combined with the well-preserved state of its historical and cultural sites, led to the designation of its urban historic centre as a national monument by the National Institute for Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) in 1938 and as a national monument in 1945.

Besides the rich architectural and urban-istic set that the city currently possesses, it also stands out for its position in the preservation ranking of the ICMS Cultural Heritage. It is among the top in the preservation ranking of Minas Gerais, occupying the first place for some consecutive years. This position indicates that the municipality executes a preservation policy for cultural assets that presents a good preservation index of its collection and that meets the required requirements, such as the maintenance of a cultural heritage council and of heritage education projects for the constant integration and awareness of the residents with the valorization of this heritage. Its position in this ranking also results in it receiving the biggest share of the ICMS Cultural Heritag e4.

-

4.1.2 The Cultural Heritage Subfield

Every space is hierarchized and reflects the social hierarchies and differences influenced by naturalization—resulting from enduring social inscriptions in reality. The same applies to the domain of culture. Like any social universe, the position of the agents within the structure relies on the possession and volume of the capitals that distinguish and rank their interests and knowledge. Depending on the capitals possessed, an agent is endowed with the capacity to mobilize what is necessary for accessing goods and services. In each field, the appropriation and both material and symbolic possession of goods represent a means of exercising and affirming domination (Bourdieu, 2013).

In this sense, when conducting the preliminary survey of the main SR related to heritage, a wide list was observed – a priori not hierarchized – of what the different audiences understood as heritage. The cultural assets known by the population are churches and the assets located around churches. The most cited were: Catedral Basílica de Nossa Sen-hora de Assunção (Cathedral Church); Praça

Cláudio Manoel (Cathedral Square); São Pedro dos Clérigos Church; Nossa Senhora do Carmo Church; São Francisco de Assis Church; Ar-quidiocesan Museum of Sacred Art (Cathedral Museum); João Pinheiro Square (Minas Gerais Square). Both the museum and the squares mentioned were treated by the respondents as related to the churches, composing a kind of se t5.

On the other hand, there were monuments that, despite being official, were hardly mentioned: Igreja das Mercês, Casa de Câmara e Cadeia, Casa Alphonsus Guimarães, and Morro Santo Antônio (archaeological patrimony). The Municipal Library, located in the historic centre, and the Church of Nossa Sen-hora Aparecida, located in the Cabanas neighbourhood, were referenced as heritage sites, although they are not. This inclusion may suggest a tendency to label a church as a heritage site, possibly indicating a challenge in discerning which of the various buildings and houses in the historic centre qualify as heritage sites. These assets were identified by 62% of the participants, while another 30% referred generically to the heritage assets they claimed to know, and 8% stated they were unaware of any heritage assets.

The appropriation of cultural heritage is one of the forms of domination within the cultural sphere. However, it is clear that heritage also embodies a social dynamic with specific values and relationships, thereby organizing itself as a microcosm that connects with and is embedded within the broader cultural landscape. By defining cultural heritage as a subfield, we can view it as a realm of power, allowing us to delineate the values and capitals that underpin it and to uncover the struggles, interests, and relationships that the involved agents strive to maintain or alter.

Another characteristic of coexistence with heritage is religious practice. Attending masses and events at churches is the most common activity among participants. Visiting monuments is noted as a sporadic practice, occurring at intervals of years and motivated by occasions such as receiving visitors or relocating to another city. Only 14% indicated they have never visited a monument. However, indirect interactions play a central role in engaging with heritage. A total of 86% visit the historic centre weekly to daily, with 52% being daily visitors. These other forms of interaction are primarily motivated by working in the area, conducting routine activities for commercial purposes such as shopping in stores, markets, and participating in financial activities at lotteries and banks, as well as engaging in leisure activities. The various activities that are part of the population's routine bring them closer, at least spatially, to heritage assets.

Concerning the disclosure of information about heritage assets, 48% of the participants indicated that issues exist. The lack of access to information was linked to the necessity for the city government to enhance the dissemination of this information, the undervaluation of heritage, and the absence of a personal habit of researching and staying informed. In terms of monument accessibility, 64% of the interviewees responded positively. Those who claim not to have any knowledge about the availability of information and access constitute 10% of respondents.

Access to and the level of knowledge influence the appropriation of heritage assets that are also reflected in the physical space. This contributes to visualizing preferences and the ways in which goods and services are appropriated in the field, allowing for the projection of established structures. In this manner, the social representations of cultural heritage, expressed through images, opinions, and attitudes as they are formed within social spaces, become embedded in naturalized social inscriptions, both in bodies and in societal order, which are evident in movements, body expressions (poses), and postures practiced within the space.

The relationship with tourism, its economic value, the lack of disclosure and investment, the lack of awareness among the population, the connections with culture, leisure, beauty, and significance, are notions associated with the social representations of cultural heritage. This heritage serves as the basis for tourism attraction to Mariana, making the relationship considered positive for promoting tourism (benefits) and negative due to its underdevelopment. The economic value of heritage is conveyed through the belief in the direct impact of preservation on the municipality's economy. In this context, there is an expectation that enhancements in preservation can elevate tourism to a major economic activity within the municipality.

The field entails a competition for cultural legitimacy, actively seeking distinctions that define its uniqueness and attributing these distinctions to a group, all while being imbued with legitimacy. The recognition and valuation of heritage as a crucial asset worthy of preservation by various social groups should be viewed as part of a dynamic process of dispute and negotiation among agents from different social groups, functioning as a generator of meaning. In the production of social representations (SRs), the groups that create the social representation of a specific object assign characteristics to it based on their association with a particular social context. Consequently, several consensus-driven visions of reality emerge, unique to each group (Jodelet, 1989). This phenomenon occurs because social representations are not formed in a social vacuum; rather, they are embedded within the social landscape created by agents through cooperation and conflict (BOURDIEU, 1996). Thus, this subfield facilitates the inclusion of social agents within a contested context where, depending on the valued capitals in the operational logic of the field, some agents possess greater capability to impose their worldviews than others.

The main reason for the complaints was the lack of publicity. Participants believe that increased publicity would attract more tourists to the city, and they also attribute this lack of awareness to the community itself, which contributes to the issues surrounding the appreciation of the heritage. In the questionnaires, culture was hardly mentioned; however, those who did refer to it highlighted the historical and cultural significance of these assets, as they attest to the city’s history and origins and showcase the people who are part of that history. Other comments emphasized the beauty of the preserved assets and the recreational and touring activities that the heritage offers. Overall, whether explicitly or implicitly, participants affirm that heritage is important.

These notions are reflected in the various ways of understanding that emerge from the different experiences social groups encounter. Finally, based on the characteristics of the context regarding the production of the SR about heritage, it is necessary to present what, in the opinion of the participants, should be preserved to become heritage. Many indicated that nothing remains, which was justified by the sufficiency of the existing heritage or the youth of the neighbourhoods. For these individuals, there seems to be a connection between what is old and heritage, implying that since the neighbourhoods are perceived as recent, there is nothing to preserve. They also tend to view cultural heritage as something already identified, established, and complete. Some expressed uncertainty about whether anything should be preserved because they could not recall anything at the moment or were simply unaware of the heritage.

In the discussion about what the interviewees consider heritage, the preservation of Mariana as a whole was mentioned to enhance the visibility of the town and its districts, as well as to underscore its status as the first capital of Minas Gerais. However, the historic core of Mariana, along with that of five out of the nine districts (Camargos, Furquim, Monsenhor Horta, Padre Viegas, and Santa Rita Durão), is already protected, which suggests that these interviewees are unaware of this protection for these urban areas. The churches, particularly the older ones, were also identified as assets that should be preserved; however, they included churches that are already listed and currently closed for restoration. In this instance, we observe that the meaning of preservation has become an action aimed at increasing care and attention toward these assets. This further indicates that the concepts of "tombamento" (listing a site as protected cultural heritage) and preservation may not be linked in people's understanding of heritage. The idea of preservation encompasses a broader scope than the status of the object (heritage asset) itself; preservation directly serves as a synonym for care.

Other objects and locations mentioned included: the cross at São Judas Tadeu Square, the chapel in the Santo Antônio district, the Lapa Cave (part of the Antônio Pereira district in Ouro Preto), a large house in Padre Viegas, a gold mine in the Santo Antônio district, the House of Culture, the Railway Station (designated as municipal heritage), the square belonging to the Diogo Vasconcelos municipality (near Mariana), the square in the Chácara district, and the old sidewalk in the Passagem district, which is currently being replaced with asphalt. UNIPAC was also suggested due to its educational function. Among these items, we observed that: the mention of already listed assets indicates a lack of awareness that they are already protected; the sites and assets that do not belong to Mariana were likely suggested because of the daily influx of residents from neighbouring towns into Mariana; and there is a notion that heritage serves as a place for living and leisure, which is why some squares and courts should be transformed into heritage sites.

In general, these ideas, beliefs, and explanations are present in the social representations of Mariana's cultural heritage. Among the cultural assets that are recognized and acknowledged by the interviewees, we observed that the most well-known churches and squares are those located in more prominent areas, such as the São Pedro dos Clérigos Church situated at the top of Dom Silvério Street on São Pedro Hill, which is visible from many locations in the city. This is also true for the "Praça e Igreja da Sé," "Praça Minas Gerais," and the "Duas Igrejas," which are found on two of the main streets in the centre. This suggests that visibility (location), daily life (passing through these spaces), and social practices (masses, weddings, and leisure activities) are likely the primary factors contributing to the knowledge constructed about the heritage. Participants who claimed to know nothing or who stated they had never visited any monument are not very representative among the respondents. This indicates that it is unlikely to live in Mariana and remain unaware, at some level, of the cultural assets regarded as heritage.

4.2 . Social Representations of the Heritage in Mariana

Social representations (SRs) are guides for interpreting aspects of reality present in the references, practices, and relations maintained with a given object. This practical function motivates the formation of an SR. In this sense, the first action of this stage of the analysis consisted of mapping values, types of interactions, and opinions about cultural heritage to identify some characteristics of the context in which these representations are produced.

Most of the views used in constructing this mapping are based on the perspective of the walker, that is, those who pass by the heritage properties while commuting to work, relaxing in the squares, or shopping. The position of a walker and the resulting observations in relation to these assets seem to be the primary source for building knowledge about heritage among the population in Mariana. For instance, there is recognition that certain churches, squares, and museums are heritage sites, even while there is limited or no understanding of these assets. This also brings forth another aspect of coexistence with heritage, which is its naturalization. This is one effect of the representations that, by familiarizing the heritage – an initially unknown and distant object – adds a new shared reference without altering the subjects' perception of the broader context.

There are various meanings, opinions, and perspectives on heritage due to differing subjective and social filters – such as emotions, values, channels of information (media and scientific), and social conditions – through which individuals develop their representations. Recognizing this diversity, we aimed to identify the Social Representation (SR) and examine the social position in the dynamics of valuing representations of cultural heritage. To achieve this, we interviewed residents, tourism agents, members of municipal administration, and individuals involved in preservation policy. Using the categories established by Jodelet – conditions of production and forms of circulation; processes of elaboration and states of representation; epistemological status—we identified four types of representations.

-

a. The first aligns with the official discourse (IPHAN and IEPHA) regarding cultural heritage, its significance, and the actions for its preservation. This type of shared understanding is typical among those involved in implementing preservation policies, such as interviewees A and B, who hold appointed positions linked to the Secretariat of Culture, Tourism, and Heritage. They believe that the effectiveness of municipal policies can be measured by the results seen in the ICMS Cultural Heritage. They use formal terminology and language to discuss heritage. They are knowledgeable about Mariana's history, and this understanding is tied to their educational and cultural background.

-

b. The second representation is based on a conception of heritage that is connected to the meaning of life, as well as the processes and moments in each interviewee's personal history. This representation is common

among residents who engage in cultural production activities and those involved in civil representation, such as participants D, E, F, G, and H. Individuals who hold this type of social representation are generally dedicated to producing and sustaining culture in a context where cultural expressions are perceived to be changing and fading away. Consequently, they believe that their activities contribute to heritage by fostering a sense of belonging among other residents. Heritage is seen as a product of culture and local history.

-

c. The third conception also views heritage as a product of local culture and history. They define cultural assets in terms of the institutions of protection (both material and immaterial), yet they adopt a more critical stance regarding the policies enacted as they relativize the position held by the ICMS Cultural Heritage in relation to the appropriation of cultural assets by the local population. They highlight issues with the structure of the Secretariat of Culture, Tourism and Heritage and the lack of a specialized technical team responsible for heritage-related matters. They provide a contemporary perspective on the history of Mariana. Consequently, this representation incorporates the social problems arising from the influx of people drawn to work in the mining companies. This type of representation was noted in interviewees C, O, and P, who are also members of the Municipal Heritage Council.

-

d. The fourth type of representation shares a common interest in the development of tourism in Mariana. In this regard, several characteristics emerge, such as the belief that heritage serves an economic function, the view of heritage as a tourist product, the need to promote this tourist attraction, and the concern for the future following the dam failure. Knowledge about heritage within this group ranges from medium to high. They acknowledge that cultural assets encompass both material and immaterial aspects. Some interviewees link heritage with culture. This group consists of individuals directly involved in tourism development activities in the munici-

- pality, along with some local residents. This representation was identified in I, J, L, M, and N.

The types of representations identified indicate that the characteristics resulting from professional occupation, the institutions they represent, and their identity as residents are aspects that shape the various forms of social representation of cultural heritage in Mariana. Another characteristic observed in the identified representations was the presence of thematic axes that direct the production of perspectives regarding the heritage. These correspond to:

-

a) Definition of heritage by material and immaterial goods;

-

b) Inherent relationship between

heritage and tourism;

c) Understanding that heritage is culture;

d) Relationship with mining.

4.3 Characteristics of the Cultural Heritage subfield: positions, disputes and legitimacy

The existence of these axes does not imply a symmetry between them. On the contrary, it is noted that some are stronger than others, meaning they are found in a greater number of social representations. Nevertheless, they indicate the presence of themes or elements that form transversal bases in the creation of these representations. These axes correspond to what Moscovici (2004) referred to as themata, in that they are structuring elements of discourse and demonstrate a certain stabilization of meaning over time.

We can observe that these axes respectively relate to the comprehensiveness of the scientific and formal knowledge about heritage (IPHAN and constitutional definition - art. 216), the interests and concerns regarding economic diversification and investment in the tourism sector, and the cultural integration of individuals. In other words, they are shaped by elements that combine the economic, cultural, and social contexts in which the representations developed. This development occurs because social representation is influenced by the needs, interests, and desires of the group from which it originates.

The position within a given social space is structured by the volume of capital that individuals possess, which includes economic, cultural, symbolic, and social types. This capital is unequally distributed, as cultural and material goods are appropriated based on each agent's circumstances, ensuring distinctions between positions. The starting point for identifying which representation is legitimized and which disputes are present was the positioning of the interviewees, defined by the volume of capital through salary range, education, relationships maintained, and recognized prestige, in the subfield of Cultural Heritage.

The proportion of capital held by the agents shapes access to the goods and services within a specific field. The mode of appropriation occurs through the alignment between the capital available to the agent, which determines their position, and the requirements and regulations that govern this field in relation to a shared interest, in this case, cultural heritage. Thus, by identifying how capital is distributed among the interviewees, who possess varying levels of resources and competencies, we can understand how this subfield is organized. Concerning the capitals that position the agents, we found that:

^ Economic capital - there is a trend that those most involved with the estate (level of interaction and knowledge) are located in the salary range of 3 minimum wages or more (10 out of 15 respondents);

^ Cultural capital - the embedded type has more weight in shaping knowledge about cultural heritage than the institutional type;

^ Social capital - has a greater capacity to mobilize resources in relation to heritage those in the traditional resident condition;

^ Symbolic capital - Traditional residents involved with maintaining the local culture have greater status, since they are recognized as holders of this knowledge.

The best-positioned agents in this subfield are agents A, D, F, and P, who possess the strongest social and symbolic capital as members of the traditional resident group and also have greater knowledge about the heritage assets (incorporated and institutional cultural capital). Despite their influence and capacity for mobilization regarding cultural heritage, only agents A and P engage directly in municipal preservation policy. Agents D and F are producers and promoters of culture but show no interest in this type of political action. The representation of interviewees D and F informs personal initiative practices aimed at producing materials that impart knowledge, foster belonging, and preserve cultural manifestations. They believe that this movement should remain separate from municipal policy, particularly as interviewee F questions the reliance on investments in cultural manifestations. Thus, despite D and F's considerable mobilization capacity, they prefer that their practices continue independently of politics.

For Bourdieu, dispute is inherent to the relationships among the strengths of agents within the field. These four agents embody two modes of action for valuing heritage: one involves engagement in the implementation of specific policies, while the other pertains to the defense of personal and non-institutional actions aimed at preserving local culture. However, a more direct form of dispute can be identified in the SR of these agents. Three representations are manifested in this group (types A, B, and C), with the types "A" of agent A and "C" of agent P conflicting at the institutional level, as they belong to entities responsible for municipal preservation actions (municipal administration and COMPAT).

The type "C" representation suggests that the current management of the Secretariat lacks an adequate structure to address interests related to cultural heritage. The absence of specialized professionals to form a technical team within the Secretariat and the establishment of a specific secretariat for heritage are argued as essential for developing a more effective preservation policy that can encourage broader participation from the community. In contrast, the type "A" representation asserts the effectiveness of heritage preservation based on the quantity of preserved assets and the outcomes of the ICMS Cultural Heritage. In local politics, the crucial issue is the maintenance of existing practices – the types of professionals involved, the organization of the sector, and how efficiency is assessed – elements that the type "A" representation supports and that the type "C" representation critiques, calling into question the organization of the sector and challenging the evaluation of effectiveness based on the results reflected in the state preservation ranking.

Despite the differences and disputes, we found that the three types of SRs presented by the four primary agents in the subfield possess social legitimacy. The subjects embodying these SRs are acknowledged in the community as holders of knowledge and/or guardians of heritage assets. We identified that these SRs share a common appreciation for culture and historical knowledge, relating heritage to cultural identity. These aspects render culture a socially valued element within this subfield. This forms the basis of the SRs for the participants from the entities responsible for heritage preservation actions in the municipality (members of COMPAT, those in the Secretariat's heritage sector, the Chamber's heritage sector, and IPHAN's office) who are best positioned within this social space.

In summary, we verified that those who hold representations rooted in cultural knowledge, acquired through incorporated cultural capital, and who possess the social capital of traditional dwellers are the ones with greater power to configure and act regarding heritage. However, the assumption of positions of responsibility and institutionalized action is not contested by this influential group (those with type "B"). We also discovered that disputes at the institutional level relate to performance and efficiency evaluations by ICMS, which impact the reorganization and expansion of the heritage sector within the Secretariat of Culture, Heritage and Tourism. Finally, culturally grounded knowledge and perspectives are the most valued and recognized components in representations of heritage. Consequently, the belief in the economic role that heritage plays (or could play) in tourism – a characteristic identified in the context of the production of the SRs – is more prevalent among those seen as not appropriating or valuing heritage.

5. Conclusion

The objective of this article was to analyze the power disputes between social representations regarding the appropriation and social legitimation of cultural heritage in Mar-iana/MG. To do so, we problematized the empirical reality of Mariana/MG, which has an abundance of this type of asset and an asymmetric dynamic regarding its appropriation, use, participation, and definition of what type of assets should be considered heritage and by whom.

The physical presence of the listed material assets and the central location of some heritage assets make this heritage a part of the daily lives of Mariana's residents. Through the perceptions, viewpoints, information, and opinions that shape the context of SR production, we find that people generally recognize and appreciate certain assets as heritage. However, this acknowledgment is often accompanied by a lack of understanding about the history and details of these assets, as well as confusion between what needs to be documented and what has already been formally preserved. Overall, heritage is deemed important and linked to tourism, given that it serves as the main attraction. These perceptions are shaped more by sensory experiences tied to the presence of heritage in everyday life than by information and knowledge from official sources.

The abstract concepts such as “tom-bamento,” preservation, and cultural heritage are transformed into concrete images associated with how people come to know and access this heritage. Thus, the presence of heritage assets is understood in various ways, depending on the social experiences of individuals through which the heritage is recognized and placed on a scale of value and judgment. Analyzing the characteristics of the social context of social representations regarding heritage, along with the four identified social representations, we observe that two perspectives underpin these representations: the economic and the cultural. The economic perspective lacks institutional and social legitimacy and is found in the views of those who have no direct connection to heritage preservation. Nevertheless, it is widely circulated among residents to justify the relevance and benefits of preservation. In contrast, the cultural perspective aligns more closely with the language and discourse of heritage protection agencies, its adoption correlating with a certain level of education and encapsulating the aspect deemed legitimate regarding modes of appropriation and understanding.

In relation to the four types of representations identified among those who maintain proximity to the heritage, types "a," "b," and "c" correspond to approaches rooted in culture and, consequently, in the level of cultural capital held by their representatives. Despite the social differences arising from professional occupations, the institutions they represent, and their identity as residents—fac-tors that reflect in the formation of these rep-resentations—these three types possess cultural capital that enables them to understand the definitions and official policies regarding cultural assets, as well as to have a profound knowledge of the history of Mariana, thereby attributing significance to heritage in the formation of cultural identity. This grants them social legitimacy. Type "d," on the other hand, combines economic and cultural foundations in the valuation of heritage. Its representatives emphasize the importance of the culture represented by the heritage while simultaneously highlighting the centrality of heritage for the economic development of the municipality. They believe that as tourism grows, the population will become more aware of and appreciate the heritage.

According to Moscovici, "Everything that prompts our actions, fulfills a function, and positions us in social relations adheres to a dominant representation; that is, the one with a higher degree of anchorage and, consequently, of legitimization and sharing within the social environment" (1978, p. 272). Therefore, in the context of cultural heritage preservation, the economic perspective holds more sharing power and has greater popularity, while the cultural perspective is regarded as legitimate, meaning it carries recognition value (status).

Concerning the positioning of agents in the subfield, the SRs elaborated based on the culture transmitted through education and access to cultural goods and services add legitimacy to the agents, thereby contributing to the maintenance of their position. In practice, this results in the perception that most residents do not value the heritage. This viewpoint is commonly held among the participants of this research and was expressed regardless of the type of relationship with preservation (either indirect or direct).

To conclude, we would like to emphasize one of the theoretical limitations of this research: the understanding of the field’s functioning based on the identified representations. Field theory cannot be reduced to the concept of a field. In structuralist constructivism, both field and habitus are interrelated, as social genesis is shaped by objective structures that are independent of the agents’ wills, in addition to perception and action schemes (Lima; Campos, 2015). However, the use of this concept was the chosen method to address the dissertation's objectives and the timeline for its completion. Integrating the concept of field with TSR enabled the introduction of issues related to inequalities in access to goods and services, which hierarchize and impact the dynamics of subject legitimacy and their representations.

This issue could have been further developed by introducing the concept of habitus and understanding its operation within this subfield. To achieve this, we must pause at the distinction between the concepts of social representation (SR) and habitus. This is a delicate distinction, as both concepts prescribe behaviours and actions that function automatically. However, what appears automatic in representation is the convergence between interpreting the situation and the content of the representation (Lima; Campos, 2018). By concentrating on conflicts between groups, we limit ourselves to understanding representations merely as integral symbolic forces. According to Bourdieu (1996), representations manifest as forms of knowledge residing within each habitus (practical sense) that directs what agents do, know, and perceive in various situations. Incorporating this concept would enable us to analyze the influence of the acquired preference system on the construction of SR, thereby understanding the process through which representations express objective structures. Nevertheless, through our reading, we were able to consider how representations are embedded in the dynamics of valuation arising from the competing interests between social groups. This enabled us to examine the functioning of these representations and the socially valued elements in the various ways of interpreting heritage.