Sociocultural and socio-psychological factors of entrepreneurial potential in the Russian Arctic

Автор: Anton M. Maksimov, Anna V. Ukhanova, Tatiana S. Smak

Журнал: Arctic and North @arctic-and-north

Рубрика: Northern and arctic societies

Статья в выпуске: 33, 2018 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article discusses the theoretical problems of the entrepreneurial potential of the population on value orientations dependence, understood as the behavioral imperatives of a particular culture. The text of the article considers entrepreneurship primarily as a socio-psychological and sociocultural phenom-enon. Entrepreneurship as a socio-psychological phenomenon is considered in the context of theories of behavioral economics, but as a sociocultural - based on the research tradition established by M. Weber. The authors postulate a thesis on the determining nature of the influence of the value system that domi-nates in a particular society on the level of entrepreneurial potential. The authors briefly set out the main approaches to the measurement of values in the social sciences, in particular, the approaches of M. Rokeach, R. Inglehart, G. Hofstede and S. Schwartz. The situation with the development of entrepreneur-ship in the regions of the Russian Arctic is presented in general terms, the specific problems that businesses face in the Arctic zone of the Russia are shown. The uniqueness of the Russian Arctic as a cultural macro-region is emphasized, on the basis of that a hypothesis is put forward about the special sociocultural condi-tions for the development of Arctic entrepreneurship compared to other territories of the country, mani-fested primarily in a specific system of values. Authors propose a synthesis of the methodologies M. Rokeach, R. Inglehart and S. Schwartz for a comprehensive study of the Russian Arctic' inhabitants value system.

Entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial potential, value orientations, behavioral economics, the Russian Arctic

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/148318510

IDR: 148318510 | УДК: [316.334.23:334.722](985)(045) | DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.157

Текст научной статьи Sociocultural and socio-psychological factors of entrepreneurial potential in the Russian Arctic

In the Message of the President of the Russian Federation to the Federal Assembly on March 1, 2018, small business is listed as one of the four large-scale reserves for the country's economic growth. The report emphasizes the need to increase the availability of business lending, reduce administrative pressure, form their digital platforms, simplify tax reporting, provide small businesses with professional staff, and create a favorable environment for start-ups. As part of the state program of the Russian Federation “Economic Development and Innovation Economy”, more than 15 billion rubles were allocated for the implementation of these and other entrepreneurship development projects in 2018. It confirms the fact that state authorities consider small businesses

∗ For citation:

significant for high rates of economic growth in the country.

Nevertheless, despite the regularly set ambitious objectives and the efforts made to develop small business, the small contribution of small business to the creation of gross domestic product remains a distinctive feature of the Russian economy. According to Rosstat, the share of total value added to small enterprises in the country's GDP in 2015 was 13.8%. However, in the period from 2004 to 2015, this indicator showed no significant changes, being in the range from 11.9 to 15.1%1. Cfr, in the European Union (EU) as of the beginning of 2014, the contribution of small business to the EU countries' GDP was 57% [1, Slesareva E.A., Terskaya G.A.].

Speaking about the contribution of small business to the economy of Russia, it is necessary to remember that the Russian Federation is a complex mix of regions significantly differentiated regarding socio-economic development, geographical location, natural and climatic features, and cultural characteristics. Thus, the number of small enterprises per 10,000 people in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation in 2016 differed by more than 17 times (from 26 in the Republic of Dagestan to 444 in St. Petersburg)2. From this point of view, research that concentrates its attention on the small business development in the regional aspect, considering the natural-geographical, economic and socio-cultural features of the territory, is becoming highly relevant.

Entrepreneurship in the Russian Arctic

If we turn to the consideration of the main areas of regional research in recent years, we should note a significant increase in interest in the development of Russian macroregions, in particular, the Far East and the Arctic. In many ways, these trends are associated with close attention of the federal center to these territories. But if in the Far East a new round of development has already been launched and the first results have been obtained (as of 2017, the FEFD accounts for a quarter of all foreign investments of Russia; it has 13 priority development areas and a significant excess of the average Russian growth rates of industrial, rural economic production, and con-struction3, then the Arctic we only feel the positive moments of the pioneering and re-constructive development of its vast territories.

A unique role in these processes, undoubtedly, should belong to a small business. Thus, in the work of researchers of the Arkhangelsk Scientific Center of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the quantitative and qualitative development of small and medium-sized businesses in the Russian Arctic is considered one of the most important indicators for assessing the effectiveness of regional socio-economic policy [2, Provorova A. et al., p. 61]. In the opinion of one of the leading Russian northern experts — A.N. Pilyasov, the dialectic of the Arctic develop- ment determines the responsibility of entrepreneurship for maintaining the territories in the long term and its rapprochement with social entrepreneurship. The first is explained by the fact that during periods of changes (falling prices for the main product, economic sanctions) there is a collapse or at least a loss of stability of large resource corporations that form the basis of the Arctic economy, and then the era of "super-organizations" is replaced by the era of entrepreneurship. The large social role of the Arctic entrepreneurship is to overcome the “collective insecurity” resulting from the fact of survival in areas with adverse conditions. Entrepreneurs here support a certain level of people's life: they deliver goods and provide essential services, create public utility infrastructure, provide transportation services, etc. All this makes A.N. Pilyasov distinguish the Arctic entrepreneurship in a separate category. At the same time, the author notes the weak attention of both government officials and representatives of public organizations, and scientists to this phenomenon [3, Pilyasov A.N., Zamyatina N.Yu.].

Speaking of Arctic entrepreneurship, it is necessary to note its underdevelopment compared with the average Russian level, as evidenced by official statistics. So, in the regions whose territories are even partly related to the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation (from now on - the Russian Arctic), the birth rate of organizations is lower than the Russian one by an average of 25%4, and the number of small enterprises per 10,000 population and the proportion of people employed in small enterprises - by almost 30%5. To understand the causes of this phenomenon, it is necessary to identify the main factors influencing the development of small business in the subjects of the Russian Arctic.

The results of a study of the Russian sector of small and medium enterprises, presented in the 2015 Report, show that the critical problems of its development are:

-

• instability of legislation in the field of tax and financial regulation;

-

• limited access to sources of financing activities: the high cost of financial resources, the lack of long-term investment funds, stringent requirements for the borrower, long periods for consideration of applications;

-

• preservation of administrative barriers;

-

• limited product sales markets: the inability to compete with large enterprises and state-owned companies in certain sectors of the economy, problems of access to government order and procurement of natural monopolies and companies with state participation, issues of access to foreign markets6.

These problems are more or less relevant to the entire territory of the Russian Federation and do not explain regional differences in the development of the small business sector. From this point of view, local conditions and features of the Arctic regions are of particular interest. Generalization and systematization of the aspects of leading economists from the Northwestern [4, Vit-yazeva V.A.; 5, Zhideleva V.V .; 6, Pilyasov A.N.; 7, Lazhentsev V.N.] makes it possible to single out the following factors hindering the development of small business in the Russian Arctic:

-

• low transport accessibility and remoteness of the Arctic regions: a significant lag of the Russian Arctic from the foreign Arctic territories both in the speed of cargo delivery and in the density of the road network. It negatively affects the competitiveness of enterprises and increases the share of the transport component in the cost of production (up to 60% of the final product's value) [8, Shpak A.V.];

-

• high prices for heating and electricity. The heating season in the Arctic is 2–3 months longer than in the cities of the central and southern part of the country7. A similar situation is observed with electricity tariffs: as of July 1, 2018, the highest fares in Russia were recorded in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug — 8.2 rubles per kWh. Also, higher than in the country as a whole, the cost of electricity in the Republics of Komi and Sakha (Yakutia), the Arkhangelsk Region and the Nenets Autonomous District8;

-

• the need to keep northern guarantees and compensations for employees that significantly increase labor costs in the cost of production.

The system of factors determining the development of small business in the Arctic regions would be incomplete if it included only a set of objective conditions and prerequisites (economic, climatic, institutional, etc.). Changes in the second half of the 20th century, the vector of research on financial decisions led to the development of a new direction in economic science - behavioral economics and, as a result, the change of the “rational person” model to the “alternative person” model. If the former assumed that economic entities were rational in their basis and aimed at maximizing utility and profit, then the latter was seeking an explanation for the economic behavior of an individual not in changing the external conditions of his activity, but primarily in the person himself, his inner world [9 Zhuravleva G.P. et al., p. 21-22].

Entrepreneurial potential in the light of behavioral economics

The foundations of behavioral economics were laid by famous psychologists D. Kahneman and A. Tversky. In the best-known article “Perspective Theory: Decision Analysis under Risk Conditions” [10, Kahneman D., Tversky A.], the authors made conclusions, unexpected for classical economic theory, about different reactions of people to winning and losing one and the same the same amount of money, as well as considering when assessing the likelihood of certain events, misconceptions and stereotypes existing in society. This contradicted the concept of rational behavior prevailing at that time but emphasized the need for a deeper study of the human factor in the economic behavior of people, including their entrepreneurial activity.American scientists D. McClelland and D. Atkinson [11, McClelland D., Atkinson J.] developed a theory of motivation to achieve success in various activities. According to her, people motivated to succeed are more resolute, bold, mobilize all their forces and resources to achieve their goals, strive to achieve success and get approval. Another type of people — motivated to avoid failures — are often insecure of themselves and their strengths, critics fear, do not believe in achieving success. It is obvious that such people, even if they create the most favorable external conditions for them, will not engage in business activities.

The theory of transgression of the Polish economist Kozeletsky Yu. deserves special attention [12, Kozeletsky Yu.]. Transgression is the human desire to systematically overcome existing results and achievements. Transgression is directly related to the presence of a person's hubristic motivation — a persistent human desire to reinforce and increase self-esteem, self-affirmation and rivalry. It is easy to assume that the higher the person’s gourmet motivation, the greater his chance of becoming a successful entrepreneur. This thesis is confirmed by research and other scientists: both domestic and foreign. In particular, the famous psychologist Druzhinin V.N. notes that entrepreneurs are characterized by a high need for self-realization and self-affirmation9, and the Austrian-American economist, political scientist and sociologist J. Schumpeter singles out the need for power and the desire for success achieved in the struggle against rivals as the main motives for entrepreneurial activity [13, Schumpeter J.].

Among the other, most important personal characteristics of both potential and existing entrepreneurs are:

-

• ability to bear risk [14, Knight F.H.];

-

• ability to make innovations [13, Schumpeter J.];

-

• high level of internality [15, Rotter J.].

It is necessary to mention the studies of V. Zombart [16, Zombart V.], who introduced the term “entrepreneurial spirit” — a complex concept that includes risk readiness, spiritual freedom, the wealth of ideas, will and perseverance, the ability to connect people for joint work. Somewhat later, G. Pinchot [17, Pinchot G., pp. 28–48] introduces the concept of “enterprise”, i.e., the synthesis of quality, skills, abilities of a person, allowing him to find and use the best combination of resources for the production, sale of goods, works and services, to accept non-standard. But rational solutions even in the face of uncertainty, create conditions for the development of innovations and shape them, make changes, take the acceptable risk and justify it.

Socio-psychological and socio-cultural background of entrepreneurship

The qualities attributed to entrepreneurs reflect not only and not so much the peculiarities of their temperament and/or intellect, but their relation to the world around them, social institutions, cultural traditions, and collective life goals and values. In social psychology, this kind of attitude is traditionally described regarding attitude (attribution), disposition, and value orientation.

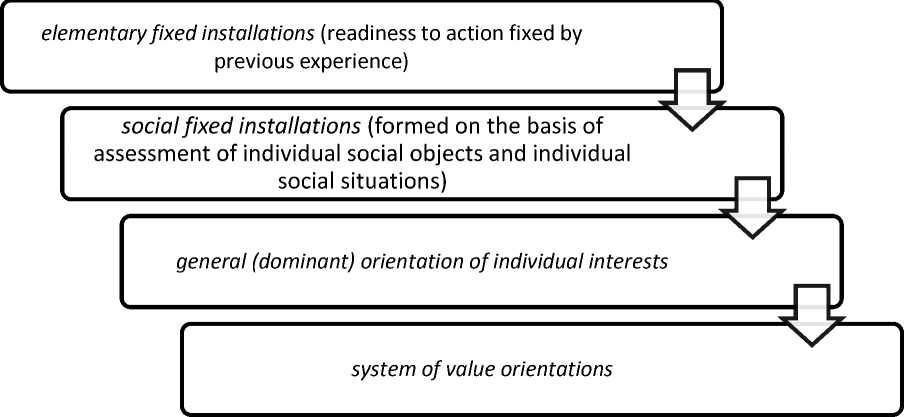

Although these categories differ from each other regarding meaning, however, to date there is an idea of their close relationship [18, Alishev B.S., pp. 46–47]. So, e.g., V.A. Yadov with colleagues believe that attitudes and values differ only by the degree of generalization, being levels of a holistic system of dispositions [19, Samoregulyaciya, pp. 35–37]. Schematically, its hierarchical structure can be represented as follows:

Fig. 1. The hierarchical structure of the individual's dispositions (V.A. Yadov).

In this hierarchy, dispositions of the highest level reflect a predisposition to identify with one or another area of social (including professional) activity (“general orientation of the interests of the individual”) and significant goals of life activity and means of achieving them (“value orientations”) [ 19, Samoregulyaciya, p. 36].

Entrepreneurship in its subjective dimension is a multiple cognitive-behavioral complex, and the principles of the entrepreneur's life activity are the product of a long process of socialization in a specific cultural environment. Consequently, entrepreneurial qualities, the propensity for entrepreneurial activity is nothing but the result of the interiorization of particular values that circulate in the sociocultural context in which the individual integrates. It means that hypothetically, ceteris paribus, related to the level of development of economic institutions, it is differences in culture that will determine differences in the entrepreneurial activity and potential in various countries or culturally different regions of the same state.

One of the first who attempted to justify the relationship between the cultural environment (in particular, value systems expressed in specific religious doctrines) and the peculiarities of economic behavior, including business, was M. Weber. In particular, it was he who substantiated the thesis that the work ethic of Protestantism promoted greater “economic rationalism” and, as a result, a higher level of development of entrepreneurship in countries with a predominantly Calvinist population [20, Weber M., pp. 67–69, 204–206].

An expert in the field of cross-cultural research, RD Lewis, in his book “Business cultures in world business”, proves that culture is a collective programming of the thinking of a group of people, expressed in sustainable values, beliefs and communication patterns that directly affect hu- man behavior, including economic" [21, Lewis R.D.].Among the studies of domestic scientists, the work of N.I. Lapin “Ways of Russia: Socio-Cultural Transformations” [22, Lapin N.I.]. The author identifies two types of society in which either traditional or liberal values dominate. In a community of the second type, priority is given to freedom and opportunities for the realization of innovations, which is a necessary condition for the development of entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial potential in the context of value research

Bulgarian researchers I.G. Garvanov and M.Z. Garvanov propose to classify approaches to the measurement of values into structural-energetic and structurally informative [23, Garvanova M.Z., Garvanov I.G., p. 16]. In the first case, each value is not assessed on its own, but in relation to other values, that is, as a unit of a hierarchically built value system. At the same time, the hierarchy of values is considered as the result of quantitative ratios between the intensity of attachment to individual values. The authors relate the approach of M. Rokeach and R. Inglehart to the class of structural-energetic theories [23, Garzanova M.Z., Garvanov I.G., p. 5–7]. In the second case, theories unite a group that postulates the dominance of specific semantically related values in a culture of a society, representing one of the poles of value dichotomies (collectivism and individualism, openness to innovations and conservatism, etc.). Among these theories, the authors relate the approaches of G. Hofstede and S. Schwartz [23, Garvanova M.Z., Garvanov I.G., pp. 8– 15]. Let us briefly highlight the specifics of each of the listed theories of values.

According to M. Rokeach, values are firm beliefs about unusual behaviors or ultimate goals in life. His method, therefore, involves the division of values into two classes: terminal, reflecting the target attitudes of individuals (what they want to achieve), and instrumental, through which the idea of approved means of making life goals is expressed [24, Rokeach M.]. In total, they were allocated 18 terminal and 18 instrumental values, covering various aspects of human activity10. According to M. Rokeach, the ranking of these values by respondents reflects the structure of the value systems of individuals. Inglehart R., as one of the initiators of the international project World Values Survey, is a leading figure in the study of values and beliefs. He points to the dialectical connection between the cultural and mental characteristics of national and regional communities and their economic institutions. One of his hypotheses is connected with the idea that intergener-ational changes in value systems (from traditionalist to modern and postmodern), due to socioeconomic changes affect the dynamics of changes in everyday economic practices [25, Inglehart R.]. Inglehart R. named an essential value scales and highlighted the scale of "traditional values -secular-rational values" and the scale of "values of survival (survival values) - values of selfexpression (self-expression values)" [26, Inglehart R., Welzel K., p. 80]. Inglehart R. and his colleagues consider the cultural imperatives of specific societies and agree that they are located be- tween the poles of these scales of values, reflecting the degree of adherence of the majority of their members to one or another (traditionalist or modernist/postmodernist) value systems. At the same time, the values on these two scales are logically linked and, as a rule, correlated. The results of empirical studies show that in countries where economic development is high, and the population does not regularly face threats of survival, a more liberal political regime is observed, more opportunities for self-realization, and people demonstrate a confidence in the future and a tendency to “development strategies” (promotion strategies); in countries that are characterized by economic stagnation or backwardness, the opposite situation is observed [27, Welzel C., Ingle-hart R., pp. 48–50]. At the same time R. Inglehart and K. Veltsel clarify that in industrial societies there is a shift primarily from traditional values to secular-rational, while the “value of survival” remains in priority, and during the transition to a post-industrial economy in all societies the value of “value of self-expression” is enhanced, while maintaining commitment to secular-rational value orientations [26, Inglehart R., Welzel K., pp. 46–54].

Based on the concept of R. Inglehart, V. Magun and M. Rudnev showed on the mothers of 43 European countries that in their population it is possible to distinguish peculiar "value classes". Using the LCA (latent class analysis) procedure, they revealed that the leading dichotomy explaining the value differentiation among the population of a single country is a commitment to the power hierarchy/commitment to social autonomy. This dichotomy integrates almost all the value indicators that R. Inglehart used to identify differences in two basic parameters — traditional-ism/secularity and values of survival/self-expression [28, Magun V.S., Rudnev M.G., pp. 13, 17].

For most countries, V. Magun and M. Rudnev identified three clusters (“classes”) of dividends. One of them united people with high levels of orientation toward submission and low indicators of orientation toward social autonomy (personal independence). The other is represented by individuals who tend to question the vertical dominance in society and the regulation of their own lives by the authorities but are not willing to actively participate in joint social actions (they could be designated as passive individualists). Finally, the third cluster is the direct opposite of the first one. Thus, researchers substantiate the idea of in-country value heterogeneity, as a result of which it is better to argue that cross-country value differences lie in the difference in proportions of individual population groups — carriers of alternative value systems [28, Magun V.S., Rudnev M.G., pp. 14-17].

The regression analysis conducted by V. Magun and M. Rudnev shows that there is a stable relationship between the probability of a respondent entering the third “class”. Parameters like the level of education of individuals and the status of their parents (leadership / non-governing position) increase, as well as countries with high GNP per capita and the countries of Northern and Western Europe [28, Magun V.S., Rudnev M.G., pp. 20–23]. In light of the topic discussed in this article, these data indicate that in countries where autonomy and independence are more common, conditions for the development of small and medium-sized businesses are more favorable, and the share of entrepreneurs among the population is higher. At the same time, in some stud- ies, the values of autonomy and the personal characteristics derived from them are indicated as being inherent to entrepreneurs to a greater degree than to representatives of other segments of the population [29, Zhuravleva N.A., pp. 144–159; 30, Kosharnaya G.B., pp. 134–135; 31, Kuzevanova A.L., p. 216]. All this serves a weighty argument in favor of a direct connection between specific value orientations and entrepreneurial potential in a given society. Hofstede G., interpreting culture as “collective programming of consciousness that distinguishes members of one group or type of people from others” [32, Hofstede G., p. 10], based on the data of cross-country comparative studies of cultural differences, developed a six-dimensional system of value coordinates determining standards and behavior patterns in a particular society. Aspects (measurements) of culture in this system are indicated to them through a set of its dichotomous characteristics: “distance of power (greater/lesser)”, “avoidance of uncertainty (greater/lesser)”, “individu-alism/collectivism”, “masculinity/femininity”, “long-term/short-term temporary orientation”, “self-indulgence/restraint” [See 32, Hofstede G., pp. 21–33]. Among these dichotomies, we can distinguish those that determine the qualitative differences in the mentality of the entrepreneurial class in comparison with other groups of the population. So, based on what was designated above as attitudes that distinguish an entrepreneur, commitment to the values of individualism, a reduced tendency to avoid uncertainty, manifested in readiness for commercial risk, and long-term temporal orientation as sociocultural characteristics of a particular society is a factor determining its entrepreneurial potential.

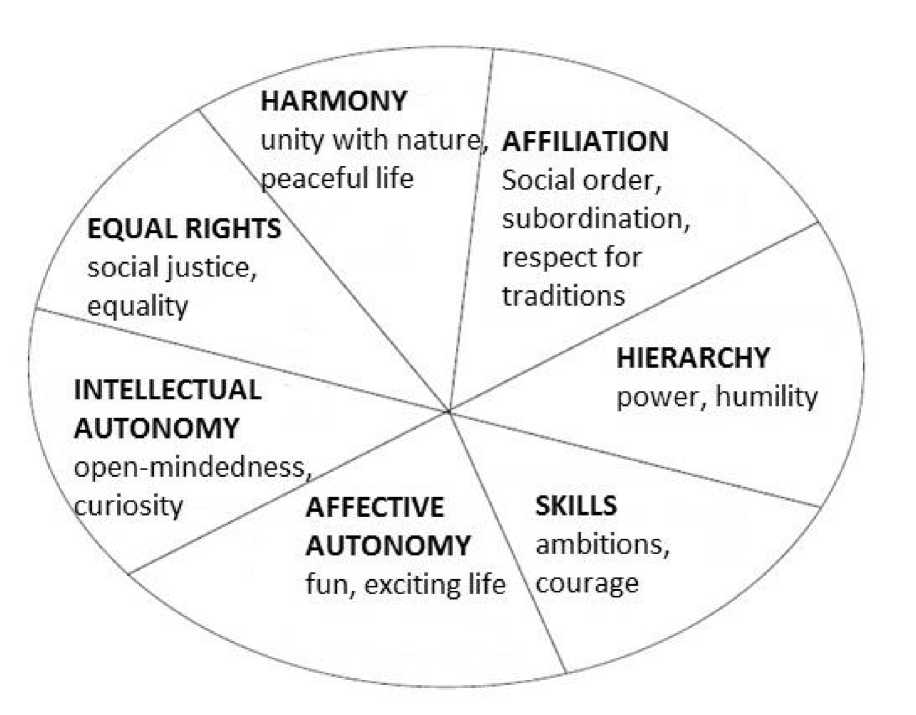

In the center for S. Schwartz, as well as R. Inglehart, is the relationship of normative value prescriptions that mediate and support specific models of social relations, and the level of socioeconomic development of territories (countries, regions). At the core of his approach is the selection of basic culturally determined value orientations prevailing in a particular society, which reflect the way in which the resolution of the fundamental problems of controlling human behavior is organized in this society. Among these problems, S. Schwartz identifies 1) the definition of the nature of the relationship and the boundaries between the individual and the group; 2) ensuring the reproducibility of social order; 3) regulation of the use of human and natural resources. The scientist a priori introduces for each fundamental problem two polar variants of the cultural “answer” (in the form of a particular basic value orientation), which are Weber ideal types, while the real situation is one or another intermediate variant. The recipe for solving the first problem lies in the choice of a position by society between alternative values, designated by Sh. Schwarz as autonomy and belonging. The solution of the second problem implies a greater or lesser commitment to either the value of equality or the value of the hierarchy. Finally, the answer to the third problem lies within the cultural dichotomy, which is expressed through the opposition of the values of “harmony” and “mastery” [33, Schwartz S., p. 39–41]. In a generalized form, the concept of S. Schwartz is presented in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. The model of the relationship of value orientations at the societal level (level of cultural integrity).

According to S. Schwarz, the prevalence of cultural values and values of “autonomy and equality” in society stimulates economic development, in turn, “membership and hierarchy” restrain it, suppressing individual initiative and creativity. Thus, determining the correlation of values of various types in the sociocultural space of the Russian Arctic will provide an idea of the prospects for individual economic programs and projects, especially innovative ones. Their success requires not only a sufficient amount of human capital but also the propensity local business to risk, its creativity, independence from the state, etc.

At the same time, S. Schwartz emphasizes that at the individual level in comparison with the societal level, the value systems are organized following other principles. In one case, we are dealing with a motivational and value system that coordinates the priority life goals of individuals and means of goal achievement that are acceptable from their point of view, which is conceptually close to the designs of M. Rokeach. In another case, we are talking about normative cultural and value orientations, reflecting the dominant, institutionally supported collective ideas of correct and deviant behavior that have coercive force for an individual. In this regard, between culturally prescribed (cultural approved ideals) and personal values (personal value priorities) in the case when they simultaneously regulate the same sphere of social practices, contrary to expectation, some disagreement may well be observed [34, Schwartz S.H., pp. 50–51].

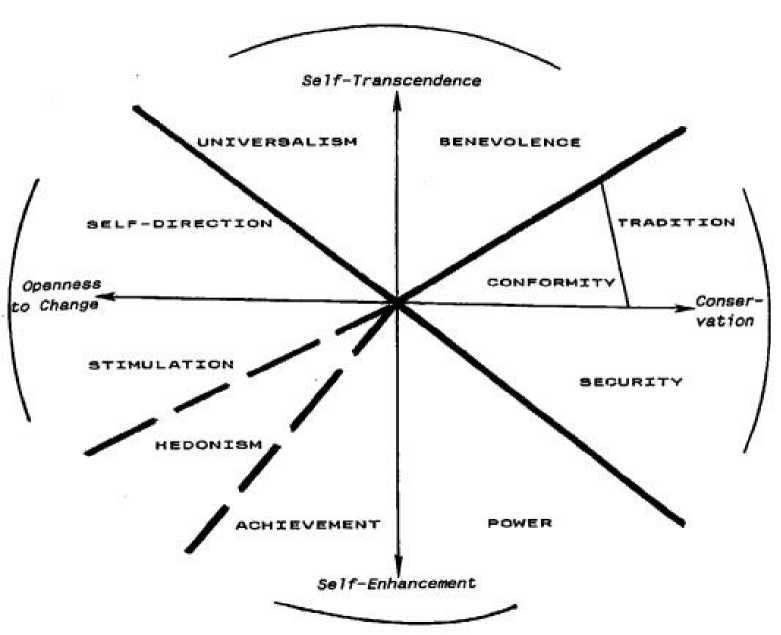

Fig. 3. The model of the relationship of value orientations in the motivational and value structure of the individual 11.

Fig. 3 shows the S. Schwartz's model, logically connecting the elements of the motivational and value structure of the personality. It presents integral indicators of value orientations, each of which aggregates a series of indicators reflecting the personal values of individuals. This model seems to be more convenient concerning analyzing the relationship between individual values, motives, and attitudes, on the one hand, and entrepreneurial activity/entrepreneurial potential, on the other. Thus, an orientation towards achievement, independence (self-direction), striving for novelty and an active, saturated life (what Schwartz calls “stimulation” [35, Schwartz S.H., pp. 7–8]) are associated with social mental features of a person inclined to entrepreneurship [36, Predprinimatelskaya kultura ..., pp. 51–53; 31, Kuzevanova A.L., p. 216; 37, Muravyova O.I. et al., p. 109]. The above-mentioned Russian sociologists V.S. Magun and M.G. Rudnev developed the ideas of S. Schwartz and modified the concept of value classes proposed by them earlier. They expanded the number of (latent) value classes to five, placing them in a two-dimensional system of value coordinates of S. Schwartz. At the same time, a “class” clearly manifested itself, possessing many valuable orientations of a potential entrepreneur [38, Magun V., Rudnev M., Schmidt P., pp. 192–199].

Methodological synthesis for the study of socio-cultural conditionality of business potential in the Russian Arctic

No doubt, in such a large country like Russia, one can single out separate macro-regions that are distinguished by their historically established socio-cultural characteristics. In turn, these features become an essential factor in structuring the routine social practices of the local population, incl. various forms of its economic behavior. The mediating link in this process is the system of value orientations, which determine the long-term attitudes, motivation and life goals of individuals. Among them is a set of specific attitudes, motives, and goals. They form the propensity of people for entrepreneurship (the socio-psychological component of entrepreneurial potential). In our opinion, the hypothesis about the direct influence of the value system specific to the residents of a particular macroregion on their entrepreneurial potential is very productive, but it requires both a methodological substantiation and careful verification. We have shown above that the enrichment of the Weberian tradition with the innovative ideas of behavioral economics allows us to form a new theoretical and methodological foundation for research in the field of economic sociology, in particular, the sociocultural and socio-psychological prerequisites of the dynamics of entrepreneurial activity. We also uncovered the possibilities of approaches to the measurement of value orientations prevailing in a particular society, to study how the cultural environment favors the development of the population’s propensity for entrepreneurship.

The project “Value and Cognitive Factors of Entrepreneurial Behavior of the Population of the Arctic Territories of Russia” was completed by the authors of this article with the support of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. It was planned to make a series of empirical studies in some subjects of the Russian Federation attributed to the Arctic zone. The research methodology is based on the concepts of M. Rokeach, S. Schwartz and R. Inglehart considered in the article.

Turning to the concept of terminal and instrumental values, M. Rokeach allows, on the one hand, to fix the prevailing personality traits of Russians with high levels of entrepreneurial potential (engaged in business, having business experience, planning to open a business), on the other, to link specific values with cultural values orientations that S. Schwartz uses to describe cross-cultural differences (see Table 1).

Table 1

The ratio of values according to M. Rokeach and value orientations according to S. Schwartz 12

|

Terminal and instrumental values (M. Rokeach)13 |

Value orientations at the societal level (S. Schwartz) |

|

Peaceful life The beauty of nature and art |

Harmony |

12 The table is based on the materials presented in the article: Schwartz S . Kul'turnye cennostnye orien-tacii: priroda i sledstviya nacional'nyh razlichij . [Cultural value orientations: the nature and consequences of national differences]. Psihologiya . Zhurnal Vysshej shkoly ehkonomiki. 2008. T.5. No 2. p. 44. [In Russian]

13 Specific values are borrowed from the Rokych test adapted to Russian realities, which was proposed in the book: Samoregulyaciya i prognozirovanie social'nogo povedeniya lichnosti: Dispozicionnaya koncepciya .[Self-regulation and prediction of a person’s social behavior: Dispositional concept]. 2nd extended ed. M .: TsSPiM, 2013. pp. 262-264. [In Russian]. Most of the formulations of these values have analogs in the original method of M. Rokich. In those cases when there were no values in the adapted test borrowed by S. Schwartz from the original method of M. Rokich, these values were indicated in formulations representing a direct translation from English of the original formulations.

|

Inner harmony |

|

|

Life wisdom Good manners (politeness) Performance Accuracy Tolerance Self control Family security National security |

Affiliation |

|

Financially secure life Sense of duty |

Hierarchy |

|

Capability Ambitiousness Public acceptance Independence Courage (in defending one’s opinion, views) |

Skills |

|

Active life Pleasures Cheerfulness |

Affective autonomy |

|

Open-mindness Freedom Creativity |

Intellectual autonomy |

|

Sensitiveness Honesty A responsibility Equality Happiness for others |

Equality |

Both the cultural value orientations of S. Schwarz and most of M. Rokeach's list of values (with rare exceptions such as Salvation in a specific Christian interpretation) can be considered universal, which is confirmed by the data of cross-cultural analysis on materials from more than 70 countries [33, Schwartz S.]. The same is true of the substantive classification of basic values (value groups) according to R. Inglehart, supported by the results of a comparative study of values in 78 countries [26, Inglehart R., Welzel K., p. 81]. Allocation of two dimensions in culturally determined value systems — “traditional values - secular-rational values” and “values of survival — values of self-expression” — makes it possible to characterize the value component of the culture of almost any complex organized community. Inter-country (inter-regional) differences in values will be expressed in the position relative to the two poles for each measurement of values in the twodimensional system of value coordinates (R. Inglehart) and / or in a specific combination of cultural value orientations, which makes it possible to classify the studied country (region) one of the seven clusters of cultures (S. Schwartz).

At the same time, the individual indicators used in the considered methods for calculating the integral value indices require adaptation to the sociocultural features of modern Russian society. Thus, among the ten key variables are used in the framework of the World Values Survey project [26, Inglehart R., Welzel K., pp. 82–83]. Such pilot surveys in the regions of the Russian Arctic (the Arkhangelsk Region and the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Okrug) showed a weak correlation with most other variables from the corresponding block. In particular, attitudes toward abortions on local material demonstrate a less intimate connection with respect for authority, national pride, and even religiosity than is supposed by the results of the World Values Survey research, which can be explained by greater tolerance for abortion in our country, incl. among the “traditionalists”. As a result, the issue of abortions, which among other things reflects gender inequality in traditional societies, has been replaced by another one that directly fixes gender inequality through the strict distribution of the social roles of men and women.

Methodological difficulties arise in the measurement of the particular index of materialistic - postmaterialistic values as a component of the index of survival-self-preservation values. According to the original method for calculating the index of "materialism - post-materialism" measurements were used for four groups of variables. Two of them characterized “materialism” — values of stable economic growth and social order, and the other two “post-materialism” — values of “green” (humanitarian and environmentalism) and libertarian values [39, Andreenkova AV, p. 75– 76, 80–81]. In the case of some variables that measure postmaterialistic values, we received a rather high percentage of those who found it difficult to answer, which seems to indicate both the abstractness of the relevant formulations and the marginality of environmentalist and libertarian discourses in Russia. Also, semantically the “green values” correspond to the values of “Harmony” (according to S. Schwartz) and can be fixed with the help of the corresponding indicators mentioned in Table 1, and the libertarian values can be reduced to the terminal value of freedom.

Similarly, “materialistic” values can be measured by their equivalents — the value of material well-being (at the expense of its versatility, it can compensate for distortions made by the economic situation while fixing people's attitudes towards policies to stimulate economic growth or combat inflation) and national security value.

Finally, it should be noted that in their research program, the authors deliberately abandoned the appeal to the approach of G. Hofstede, because his methodology was initially focused on solving specific problems of intercountry research of organizational culture in transnational corporations and was applied to IBM employees. Of course, they cannot represent all the population of a country. However, due to the pioneering nature of Hofstede's works, and the popularity of his approach to social psychology and sociology of management, we could not fail to mention the strengths of his methodology in this article.

Conclusion

This article offers a methodological substantiation of studying the phenomenon of entrepreneurship as a sociocultural and socio-psychological phenomenon. Generalization of interpretations of entrepreneurship that exist in the half-century-old scientific tradition, and also referring to the achievements of theories of behavioral economics, the authors interpret the nature of entrepreneurship as a form of economic behavior due to fixed attitudes (social attitudes) and some fundamental values and dominant cultural value orientations. These attitudes, values, and orien- tations, being widely spread in various communities (countries, regions), are the essential noneconomic factor stimulating entrepreneurial activity.

The article provides a critical analysis of the most popular methods of measuring values in terms of the possibilities of identifying statistically significant relationships between value variables and variables of entrepreneurial potential (first of all, the modus of business valuation, propensity for entrepreneurship and real entrepreneurial activity). A variant of the methodological synthesis based on the approaches of M. Rokeach, S. Schwartz and R. Inglehart was proposed.

The importance of the Russian Arctic and its special socio-cultural space in the designated research context is explained by the comparatively weak study of its constituent territories for the specificity of cultural and socio-psychological determinants of economic, incl. entrepreneurial, population behavior. In the further studies, the authors plan to fill this lacuna in scientific knowledge.

Acknowledgments and funding

The article is a part of a research project supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) No. 18-310-00167 mol_a “Value and Cognitive Factors of Entrepreneurial Behavior of the Population of the Russian Arctic Territories”.

Список литературы Sociocultural and socio-psychological factors of entrepreneurial potential in the Russian Arctic

- Slesareva E.A., Terskaya G.A. Gosudarstvennaya podderzhka malogo biznesa: zarubezhnyy opyt [State support of small business: foreign experience]. Biznes i obshchestvo [Business and society], 2015, no. 1, p. 5.

- Provorova A.A., Gubina O.V., Smirennikova E.V., Karmakulova A.V., Voronina L.V. Metodicheskiy in-strumentariy otsenki effektivnosti realizatsii gosudarstvennoy sotsial'no-ekonomicheskoy politiki razvitiya regionov Rossii [Methodological Tools for Assessing the Effectiveness of Implementation of the State Social and Economic Development Policy of Russia's Regions]. Ekonomicheskie i sotsial'nye peremeny: fakty, tendentsii, prognoz, 2015, no. 3 (39), pp. 56–70.

- Pilyasov A.N., Zamyatina N.Yu. Arkticheskoe predprinimatel'stvo: usloviya i vozmozhnosti razvitiya razvitiya [Arctic entrepreneurship: conditions and opportunities for development]. Arktika: ekologi-ya i ekonomika [Arctic: Ecology and Economy], 2016, no. 4, pp. 4–15.

- Vityazeva V.A. Sotsial'no-ekonomicheskoe razvitie Rossiyskogo i zarubezhnogo Severa [Social and economic development of the Russian and foreign North]. Syktyvkar: SyktGU Publ., 2007. 292 p. (In Russ.)

- Zhideleva V.V. Formirovanie rynochnogo mekhanizma sotsial'no-ustoychivogo razvitiya severnykh regionov [Formation of the market mechanism of social sustainable development of the northern regions]: dis. … dok. ekon. nauk. Moscow, 1997, 282 p. (In Russ.)

- Pilyasov A.N. I poslednie stanut pervymi: Severnaya periferiya na puti k ekonomike znaniya [And the last will be the first: The northern periphery on the way to the knowledge economy]. Moscow: Knizhnyy dom «LIBROKOM» Publ., 2009, 544 p. (In Russ.)

- Sever kak ob"ekt kompleksnykh regional'nykh issledovaniy [North as an object of complex regional studies]. Ed. by V.N. Lazhentsev. Syktyvkar, 2005, 512 p. (In Russ.)

- Shpak A.V. Problemy i perspektivy formirovaniya transportno-logisticheskikh sistem na Severe [Prob-lems and prospects for the formation of transport and logistics systems in the North]. Natsional'nye interesy: prioritety i bezopasnost' [National interests: priorities and security], 2010, no. 32, pp. 72–76.

- Povedencheskaya ekonomika: sovremennaya paradigma ekonomicheskogo razvitiya: monografiya [Behavioral economics: the modern paradigm of economic development]. Ed. by G.P. Zhuravleva,

- N.V. Manokhina, V.V. Smagina. Moscow; Tambov: Izdatel'skiy dom TGU im. G.R. Derzhavina Publ., 2016, 340 p. (In Russ.)

- Kahneman D., Tversky A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Making under Risk. Econometrics, 1979, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 263–291.

- McClelland D., Atkinson J., Clark R., Lowell E. The Achievement Motive. Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1953. 384 p.

- Kozeletskiy Yu. Psikhologicheskaya teoriya resheniy [The psychological theory of decisions]. Mos-cow: Progress Publ., 1979, 504 p. (In Russ.)

- Schumpeter Y. Teoriya ekonomicheskogo razvitiya. Kapitalizm, sotsializm i demokratiya [The theory of economic development. Capitalism, socialism and democracy]. Moscow: EKSMO Publ., 2007, 864 p. (In Russ.)

- Knight F.H. Risk, neopredelennost’ i pribyl' [Risk, uncertainty and profit]. Moscow: Delo Publ., 2003, 360 p. (In Russ.)

- Rotter J. Generalized expectation for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 1966, no. 80 (608), pp. 1–27.

- Zombart V. Sotsiologiya [Sociology]. SPb: MYSL'' Publ., 2003, 133 p. (In Russ.)

- Pinchot G. Intrapreneuring: why you don’t have to leave the corporation to become an entrepre-neur. New York: Harper and Row, 1985, 368 p.

- Alishev B.S. Fundamental'nye sotsial'nye ustanovki i ikh sootnoshenie sootnoshenie [Fundamental social attitudes and their relationship]. Uchenye zapiski Kazanskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Gumanitarnye nauki [Proceedings of Kazan University. Humanities Series], 2007, vol. 149, ch. 1, pp. 46–60.

- Samoregulyatsiya i prognozirovanie sotsial'nogo povedeniya lichnosti: Dispozitsionnaya kontseptsi-ya. 2-e rasshirennoe izd [Self-regulation and prediction of social behavior of the individual: Disposi-tional concept]. Moscow: CSP&M Publ., 2013, 376 p. (In Russ.)

- Veber M. Protestantskaya etika i dukh kapitalizma [Protestant ethics and the spirit of capitalism Moscow: Progress, 1990, 808 p. (In Russ.)

- L'yuis R.D. Delovye kul'tury v mezhdunarodnom biznese: ot stolknoveniya k vzaimoponimaniyu [Cul-tures in international business: from collision to understanding]. Moskva: Delo Publ, 2001, 448 p. (In Russ.)

- Lapin N.I. Puti Rossii: sotsiokul'turnye transformatsii [The Ways of Russia: Sociocultural transfor-mations]. Moskva: IF RAN Publ., 2000, 191 p. (In Russ.)

- Garvanova M. Z., Garvanov I. G. Issledovanie tsennostey v sovremennoy psikhologii [The study of values in modern psychology]. Sovremennaya psikhologiya: materialy III Mezhdunar. nauch. konf. (g. Kazan', oktyabr' 2014 g.). Kazan': Buk Publ., 2014, pp. 5–20. (In Russ.)

- Rokeach M. The nature of human values. New York: Free Press, 1973, 438 p.

- Inglehart R. Postmodern: menyayushchiesya tsennosti i izmenyayushchiesya obshchestva [Post-modern: changing values and changing societies]. POLIS. Politicheskie issledovaniya [POLIS. Political Studies], 1997, no. 4, pp. 6–32. Inglehart R., Veltsel K. Modernizatsiya, kul'turnye izmeneniya i dem-okratiya: Posledovatel'nost' chelovecheskogo razvitiya razvitiya [Modernization, cultural change and democracy: The sequence of human development]. Moscow: Novoe izdatel'stvo Publ., 2011, 464 p.

- Welzel C., Inglehart R. Agency, Values, and Well-Being: A Human Development Model. Social Indica-tors Research, 2010, no. 97, pp. 43–63.

- Magun V.S., Rudnev M.G. Tsennostnaya geterogennost' naseleniya evropeyskikh stran: tipologiya po pokazatelyam R. Inglkharta [The value heterogeneity of the European countries population: the ty-pology by R. Inglehart's indicators]. Vestnik obshchestvennogo mneniya. Dannye. Analiz. Diskussii [Newsletter of public opinion. Data. Analysis. Discussions], 2012, no. 3–4, pp. 12–24.

- Zhuravleva N.A. Dinamika tsennostnykh orientatsiy lichnosti v rossiyskom obshchestve [Dynamics of the person' value orientations in the Russian society]. Moscow: Publishing house of the Psychology institute of RAS, 2006, 335 p. (In Russ.)

- Kosharnaya G.B. Vliyanie tsennostey otechestvennogo predprinimatel'stva na integratsionnye protsessy v obshchestve [Influence of the domestic business' values on integration processes in a society]. Vlast' [The Authority], 2016, no. 9, pp. 133–137.

- Kuzevanova A.L. Tsennosti rossiyskoy biznes-deyatel'nosti: opyt sotsiologicheskogo analiza [Values of Russian business activity: the experience of sociological analysis]. Gumanitarnye i sotsial'nye nauki [Humanities and Social Sciences], 2010, no. 5, pp. 207–217.

- Hofstede G. Model' Hofstede v kontekste: parametry kolichestvennoy kharakteristiki kul'tur [Hof-stede model in the context: the parameters of the quantitative characteristics of cultures]. Yazyk, kommunikatsiya i sotsial'naya sreda [Language, communication and social environment], 2014, no. 12, pp. 9–49.

- Shvarts Sh. Kul'turnye tsennostnye orientatsii: priroda i sledstviya natsional'nykh razlichiy [Cultural value orientations: the nature and consequences of national differences]. Psikhologiya. Zhurnal Vysshey shkoly ekonomiki [Psychology. Journal of Higher School of Economics], 2008, Vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 37–67.

- Schwartz S.H. Cultural value differences: Some implications for work. Applied Psychology: An In-ternational Review, 1999, no. 48, pp. 23–47.

- Schwartz S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in experimental social psychology, New York: Academic Press, 1992, vol. 25, pp. 1–65.

- Predprinimatel'skaya kul'tura molodezhi v munitsipal'nom obrazovanii: otsenka, upravlenie i razvitie [Entrepreneurial culture of youth in the municipality: evaluation, management and development] / Ed. by E.L. Andreeva. Ekaterinburg: Institute of Economics, Ural Branch of RAS Publ., 2017, 117 p. (In Russ.)

- Murav'eva O.I., Matsuta V.V., Erlykova Yu.N. Tsennostnye orientatsii predprinimateley malykh i krupnykh gorodov [Value orientations of entrepreneurs of small and large cities]. Sibirskiy psikho-logicheskiy zhurnal [Siberian psychological journal], 2013, no. 48, pp. 102–110.

- Magun V., Rudnev M., Schmidt P. Within-and Between-Country Value Diversity in Europe: A Typo-logical Approach. European Sociological Review, 2016, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 189–202.

- Andreenkova A.V. Materialisticheskie / postmaterialisticheskie tsennosti v Rossii [Materialistic / postmaterialistic values in Russia]. Sotsiologicheskie issledovaniya [Sociological studies], 1994, no. 11, pp. 73–81.