Sovereign court of Vasily III: historical and genealogical research

Автор: Korzinin Aleksandr L., Bashnin Nikita V.

Журнал: Вестник ВолГУ. Серия: История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения @hfrir-jvolsu

Рубрика: История России

Статья в выпуске: 4 (46), 2017 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The research is focused on the issues concerning personal and genealogical composition of the Sovereign court during the great reign of Vasily the Third (1505-1533). The relevance of the research is connected with the small number of works devoted to Vasily Ivanovich's reign (in particular, monographs by A.A. Zimin and A.I. Filyushkin), and with that fact that such institute of the organization of the upper class and middle class of the Russian society as the Sovereign court is insufficiently studied. On the basis of the earlier developed methodology of allocating the servant landowners who constitued the capital court, and the reconstruction of the court nobility in the first third of the 16th century, the authors for the first time analyze th e genealogical structure of the Vasily III court. It is proved that the core of the Vasily Ivanovich's court was formed by those surnames, which had already been known under his father Ivan III. However some changes are also revealed. There was a limited access to the court nobility for little-known and lowborn surnames, so the composition of the court became more aristocratic. This was partly due to strengthening of princely aristocracy represented by the Gediminovich prince's sons of Northeast Russia, as well as princes of the Lithuanian origin. The greatest number of departures on service to the capital took place from Lithuania and passed against the background of Russian struggle for Smolensk. Another understudied aspect of the court concerns Pskov accession to Moscow and the formation of Pskov service corporation. This article attempts to restore the composition of the first Pskov landowners, to determine the initial land accessory (mainly from the Novgorod land) and to trace their gradual inclusion in the capital court during the first half of the 16th century. A section about Vasily the Third's clerks concludes the publication. The composition of the grand-ducal office is studied, its comparison with the clerks of Ivan III is carried out, and a conclusion is made about a significant increase in the prestige of the clerk's service and the beginning of the folding of the dynasties of departmental employees. As an illustration, monograms and signatures of the famous clerks of Vasily III are given. The authors analyze the reasons of the substitution of monograms for signatures which was reflected in office-work of the end of the 15th - first third of the 16th century. A.L. Korzinin analyzed personal and genealogical structure of the Sovereign court in the first third of the 16th century. N.V. Basnin studied the change in traditions of the paperwork (signing, monograms, clerks' signatures) in the context of the history of state institutions.

Ivan iii vasilyevich, vasily iii ivanovich, sovereign court, genealogy, clerks, clerks' monograms, иван iii васильевич, василий iii иванович

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/14972239

IDR: 14972239 | УДК: 94(470)“08/16” | DOI: 10.15688/jvolsu4.2017.4.8

Текст научной статьи Sovereign court of Vasily III: historical and genealogical research

DOI:

Цитирование. Корзинин А. Л., Башнин Н. В. Государев двор Василия III: историко-генеалогическое исследование // Вестник Волгоградского государственного университета. Серия 4, История. Регионоведение. Международные отношения. – 2017. – Т. 22, № 4. – С. 77–90. (На англ.). – DOI:

The composition of the Sovereign court during the great reign of Vasily Ivanovich (1505– 1533) didn’t receive a proper coverage in historiography in contrast to the court of his father Ivan III and his son Ivan the Terrible. After the publication of A.A. Zimin’s book dedicated to the political development of the Russian state in the first third of XVIth century, and the popular- science monograph about Vasily III, written by A.I. Filyushkin [72; 20], Sovereign court as an association of service class people “by country” who took part in country government, did not become an object of a special research. There are separate works about Pskov accession to Moscow, the struggle of Russia for West-Russian lands in the first third of XVIth century, marriage policy of Vasily III, the composition of Boyar Duma and palace ranks [32; 31; 34; 35; 30]. In the meantime genealogical analysis of the composition and study of the evolution of the Grand Duke’s court in 1505–1533 will make it possible to understand better those changes that has affected various layers of the nobility after the reign of Ivan III, reveal the transformation of the most important sociopolitical institute of organization of the upper class of the Russian state, investigate the prerequisites of the court reforms during boyar government and at the beginning of the Ivan the Terrible reign.

The comparison of the personal composition of the court of Ivan III with the Sovereign Court of Vasily III, executed on the basis of the earlier reconstruction of the composition of the yard boyar children and senior officials [27, p. 363– 414], demonstrates that from the titled nobility at court of Vasily Ivanovich there were princes Volkonskiye, (descendants of the Chernihiv princes), Vadbalskiye and Dyabrinskiye (the Belozersk Ryurik dynasty), Drutskiye (of the Lithuanian origin), Trubetskoy (a branch of Gediminovichy), Ohljabininy, Troekurovy and Shhetininy (the Yaroslavl Ryurik dynasty), Pozharskiye and Hripunovy-Ryapolovskiye (the Starodub Ryurik dynasty), and from the Ryazan untitled nobility – Apraksiny i Verderevskie. Ryazan boyars (Izmailov’s, Bulgakov-Denisiev’s, etc.) moved to the grand-ducal service already at the end of the XVth – beginning of the XVIth century much earlier than Ryazan’s accession to Moscow happened [26, p. 144]. Glinskiye’s princes moved away from Lithuania to Russia in 1508 and with them to Moscow arrived princes Ivan Ozeretsky, Dmitry and Vasily Zhizhemskiye, Semyon Alexandrov, Mikhail Gagin, the prince Andrey Drutsky, the prince Ivan Kozlowski etc [71, p. 72–73].

M.E. Morozova, developing A.A. Zimin’s observations, believes that Vasiliy III wedding on the princess E. V. Glinskaja in 1526 promoted departure of the local nobility from Lithuania to the Moscow yard. Already in July 1526, Prince F.M. Mstislavsky (who came from the Grand Duke of Lithuania Gedimin) arrived in Russia. The grand duke Vasily III brought Mstislavsky closer to himself and gave Anastasia, the daughter of Prince Peter and tsar’s sister Evdokia, in marriage to Mstislavsky [70, p. 127–128; 34, p. 220–221]. After 1505 we find on service such untitled families as Alexandrovs, Kobyakovs (came from Ryazan), Nagie, Sobakins, Sergeevs, Levashevs, Hidyrshchikovs (from Tver), Polevye (conducted a genealogy from the Smolensk princes), Nevezhins (from Nester), Neledinsky, Matveyevs, Prokudins, Sukins, Turgenevs, Chemodanovs, Yuryevs (a branch of a family of Andrey Kobyla). It is known from the genealogical lists of the end of the 17th century about transitions to the service from Poland to Vasily III of Alyabyevs, princes of Glinsky and Drutsky (in 1508), Zhizhemsky and Kozlovsky (in 1508), Zaborovsky, princes Korkodinovs (in 1514), Krekshins (in 1514), princes of Mstislav and Raevsky (in 1526) [7, p. 9; 8, p. 168; 10, p. 206; 11, p. 6, 14, 102; 12, p. 116, 161; 13, p. 114], from “German” Alexandrov-Protopovs and Shusherins [8, p. 166; 9, p. 230], from Crimea Rostopchiny [8, p. 184], from the Great Horde Dashkovs [12, p. 96]. Apparently, the majority of departures were from Poland. Transitions of the Lithuanian nobility into Russian citizenship increased in connection with the struggle of Moscow for the West-Russian lands. Conquest of Smolensk in 1514 caused entry of a significant number of local boyars on the Moscow service [31, p. 234–243, 264–287]. Many of Lithuanian origin surnames (Bryansk and Smolensk boyars), appeared in Russia as a result of departures, were later recorded in the Dvorovaja Tetrad of the 1550s as “Dvorovaja Lithuanian”. They were considered as a personnel pool in service of the court [68, p. 141, 143, 144–146, 150–153, 155–158, 164, 187, 206–208; 27, p. 162]. Only a few of the former Smolensk boyars, taking into account special merits before the Moscow sovereign could eventually get through to the capital court. The most striking example is the history of the noble family of the Pivovs who were after 1514 taken to the Yaroslavl district and subsequently made a brilliant career during the oprichnina [25, p. 59–61; 31, p. 219, 242; 29].

Stopped their services (for a while, or forever) the representatives of surnames who approved themselves during the reign of Ivan III. Of the well-known families should be called following names: Basenkovy (this could be probably connected with that fact that Fedor Basjonok fell from grace in 1463), Novosil’cevy, Starkovy, Patrikeevs princes (because of that fact that they fell from grace in January 1499), Sogorskie, Solncevyh-Zasekiny and Shahovskie, Tulupovy, and also Belkiny (the Alexei Khvost family branch), Osokiny (from Fominsky princes), Shapkiny (branch Vsevolozhey), and also from the second-rate noble surnames should be called Aksent’evy, Bestuzhevy, Vasil’chikovy, Dubroviny, Zinov’ evy, Kalitiny, Kozlovy, Kocherginy, Kuleshiny, Kushelevy, Malechkiny, Perfushkovy, Pikiny, Rodionovy, Tolmachevy, Toporkovy, Shhulepnikovy.

Sovereign court in 1505–1533 numbered at least 860 people and the yard of Ivan III included about 840 domestics (“dvorovye”) [27, p. 363– 413]. During the reign of Ivan Vasilyevich under the conditions of personnel shortage, the need of solution of acute foreign policy and domestic issues, many birthless names got into the court. Attrition of not well-born persons, rejection of domestics (“dvorovyh”), unsuitable because of service-local (“mestnicheskij”) status, construction of a clear hierarchical structure of the court remained at the discretion of the successors of Ivan III [26, p. 147]. Indeed, if we consider the court of Vasily III, then it is possible to find about 3 times fewer persons with unclear social status than in his father’s sovereign court 2. In fact, apparently, the personnel housecleaning of the service landowners was carried out [17]. As a result, the court of Basil III became a privileged institution, the access to which for not well-born people was almost tightly closed.

The Sovereign court of the first third of XVI century had constant composition, there was created the backbone of the court, presented by the surnames that had already served to Ivan III. As a rule of thumb that the overwhelming majority of descendants from noble families, known for their service successes at the court of Ivan Vasilyevich, continued their careers in his son times. From the titled nobility we are talking about the princes of Yaroslavl (Alabyshevy, Alenkiny, Deevy, Zasekiny, Kubenskie, Kurbskie, Penkovye, Prozorovskie, Sickie, Ushatye, Shestunovy, Juhotskie), princes of Belozersk (Andomskie, Kemskie, Uhtomskie, Sheleshpal’skie), princes of Suzdal (Barbashiny, Gorbatye, Nogtevy, Shujskie), princes Gediminovichi (Bel’skie, Hovanskie, Shhenjatevy), princes of Rostov (Bujnosovy, Goleniny, Temkiny, Janovy, Hoholkovy), princes of Starodub (Gundorovy, Krivoborskie,

L’jalovskie, Paleckie, Romodanovskie, Rjapolovskie), princes Obolensky (Kashiny, Lykovy, Nagie, Peninskie, Shhepiny, Shherbatovy, Repniny, Striginy, Telepnevy Trostenskie, Tureniny), princes of Lithuania (Babichevy, Nesvickie (Nesvizhskie)), princes of Smolensk (Vjazemskie, Kropotkiny, Porhovskie), princes of Chernigov, who were on the position of servicemen (Beljovskie, Vorotynskie, Mezeckie, Mosal’skie, Odoevskie), princes of Tver (Dorogobuzhskie, Mikulinskie, Teljatevskie, Chernjatinskie, Holmskie), princes of Ryazan (Pronskie) and also princes of Yelets, Nozdrovatye, Meshherskie. Of untitled births, these are people, who left Italy and the Crimea (Aminevy, Angelovy, Larevy, Laskirevy, Trahaniotovy and Hovriny), last names from Andrey Kobyla (Bezzubcevy, Zahar’iny, Kolychevy, Obrazcovy, Hludenevy, Sheremetevy), last names from Netsha (Belogo, Mamonovy), from Fyodor Bjakont (Pleshheevy, Beklemishevy, Ignat’evy), from Ratsha (Buturliny, Zhulebiny, Davydovy, Danilovy, Zamyckie, Kologrivovy, Kuricyny, Pushkiny, Tovarkovy, Chebotovy, Cheljadniny, Chulkovy, Sliznevy), from Redega (Elizarovy, Zajcevy, Kokoshkiny, Oshheriny, Habarovy), from the Smolensk princes (Vsevolozh-Zabolockie, Bokeevy, Eropkiny, Karpovy), from the Fominsk princes (Rzhevskie, Satiny, Traviny), births connected with Tver (Alfer’evy i Nashhokiny, Borisovy, Izmajlovy, Korobovy, Sakmyshevy), with Ryazan (Glebovy, Denis’evy i Bulgakovy, Korob’iny, Sidorovy, Tutyhiny), and also Bartenevy, Bezobrazovy, Boltiny, Valuevy (from Okatij), Vladykiny, Voksheriny, Volynskie, Solovcovy, Voroncovy (ot Protasija), Vysheslavcevy, Gavrilovy, Gireevy, Golohvastovy, Dashkovy, Dedevshiny, Drovniny-Afanas’evy, Stanishhevy (Djatlovy, Kucheckie, Lazarevy), Zagrjazhskie, Zacheslomskie, Zvorykiny, Zezevitovy, Ivanovy, Karamyshevy, Kajsarovy, Kartmazovy, Kvashniny (from Nester), Kikiny, Kiselevy, Kitaevy-Novosil’cevy, Klement’evy (from Oblagini), Konstantinovy, Korsakovy, Koteniny, Krenevy, Kuz’ miny, Kutuzovy, Liharevy, Mamyrevy, Mansurovy, Melikovy, Mizinovy, Miloslavskie, Moklokovy, Morozovy (Tushiny Sheiny), Naumovy, Nikiforovy, Oznobishiny, Olad’iny (from Aleksandr Monastyr’), Oleniny, Osininy (from Prince Dmitry Galitsky), Otjaevy and Hvostovy (from Alexei

Khvost), Osor’iny, Petrovy, Peshkovy and Saburovy (from Dmitry Zerno), Pisarevy, Pisemskie, Plemjannikovy, Povadiny, Pogozhie, Priklonskie, Protas’evy, Putjatiny, Stupishiny, Sukovy, Surminy, Tatishhevy, Trofimovy, Tjutchevy, Ul’janiny-Davydovy, Uskogo, Ushakovy, Fedorovy, Hlopovy, Homjakovy, Chelishhevy, Cheljustkiny, Shashebal’ cevy, Shepjakovy, Jazykovy.

The idea of the composition of the Sovereign of the court of Vasily III can be extended by analyzing the following events. In January 1510, as a result of a bloodless march Pskov was annexed to the Grand Duchy of Moscow. The Novgorod experience of creating a manorial (“pomestnaja”) system and a service corporation was widespread to the Pskov district. But as against from Novgorod on Pskov region (“Pskovshhina”) the lands were not granted to the first-class Moscow nobility who took part in the decisive campaign and later headed the local administration [28]. Data on the circle of persons, who became the first landowners in the vicinity of Pskov, is difficult to obtain. Land descriptions were carried out in the Pskov district (“uyezd”) in 1510, 1550/1551, 1556–1559, 1562–1563 [6, p. 108–109; 24, p. 16, 40, 49, 51–53, 62, 100], but cadasters for these years, unfortunately, were lost. The payment book of Pskov and its suburbs that was drawn up by scribes G.I. Meshchaninov-Morozov and I.V. Drovnin in 1585–1587 and also scribal description of a number of the Pskov land districts (Gdovskij, Kobyl’skij, Izborskij, Ostrovskij, Voronachskij, Vyborgskij, Dubkovskij), which was made in 1585, have survived [65; 60]. The retrospective method allows for scribal books of the 1580th to reconstruct the composition of the Pskov district (“uyezd”) landlords of the 1540– 1550th. The early layer of Pskov landowners was noted in the books as the first holders of lands. In addition to scribal descriptions information about Pskov landowners in the 1530–1550th can be extracted from a variety of official documents: embassy book with the Teutonic Order in Prussia of 1516–1520s (there names of Pskov police officers and courier with letters are given), Radziwill’s archive (there are the names of the Pskov governors and boyar children on the pages of reports), the One Thousand Book (“The Tysiachnaia Kniga”) of 1550 (here are placed the names of court and city boyar children from Pskov and its suburbs), Pskov desjatni of 1556, boyar list of 1577, commemoration books (“synodics”) for “murdered into warfares” Russian warriors, the list of Russian captives etc [66, p. 6, 24, 32, 34, 40, 79, 82, 83, 122–123, 135, 158–159, 177, 181, 193, 226, 235, 245; 54, no. 46; 68, p. 98–101; 44, p. 184–185; 67, p. 202; 4, p. 157; 27, p. 220– 222]. Return thanks to fragmentarily preserved sources, it is possible to restore the names of about a hundred Pskov district landowners of the first half of the XVIth century. A careful analysis of the information from the cadasters of the Novgorod district of the first half of the XVIth century [38; 39; 40; 41; 42; 43; 45; 46; 47; 48; 49; 50; 51; 62] showed that among the first Pskov landowners there were mainly natives of all the Novgorod fifths (“pyatina”) (Novgorodians themselves, as well as their children and close relatives), but the majority were settlers from the Shelonskaja fifth (“pyatina”), which came very close to the borders of the Pskov district (“uyezd”) 3. The observations confirm the unique information of the handwritten tale “The Conquest of Pskov”, which, according to the observations of N.N. Maslennikova, arose shortly after 1510 under the pen of a contemporary or participant of those events [32, p. 98]. It says that on January 28, 1510 Vasily III brought Pskov posadniks, boyars with their wives and children, from the defeated Pskov and their lands were given to the manorial distribution, “and the boyar children were left by the great prince in Pskov for a year living with Pskov governors (“namestniki”) Grigory Fedorovich and Ivan Ondreevich, and one thousand of Novgorod landowners” [32, p. 193– 194; 5, p. 298–299]. Pskov chronicles also preserved information about leaving in the city “one thousand of boyar children and 500 of Novgorod harquebuses (“pischalnik”)” by the sovereign [52, p. 96; 53, p. 298–299]. It does not follow from these brief records that the Moscow ruler gave Pskov lands those who took part in Pskov accession, but the presence of Novgorodians in the campaign against Pskov should not be ruled out. Firstly the Grand Duke moved from Moscow to Novgorod the Great, and from there on January 20 in 1510 with his entourage drove out “to his ancestral lands to Pskov” [32, p. 191]. Of all the high-ranking participants of the Pskov “accession” (Princes I.M. Repney-Obolensky, P.V. Veliky Shestunov,

A.V. Rostovsky, G.F. Davydov, I.A. Chesednin, D.V. Khovrin, D.V. Shcheny, I.V. Khabar, I.A. Zhulebina, M.K. Bezzubtseva, A.V. Saburov, P.Ya. And M.Yu. Zakharyin, princes ML Glinsky, I.I. Kholmsky, M.D. Shchenyatev, K.F. Ushatoy, F.Yu. Prozorovsky, I.A. Buinos-Rostovsky) we find no one among the Pskov landowners. Only in the cadaster of 1585 in the Kamenskaya Guba of Gdovskij district (Uyezd) recorded a small estate of the size of 65 quarters of land, which formerly belonged to Prince I.M. Glinsky, first cousin at one remove of Mikhail Lvovich Glinsky. By 1585, the estate was in the possession of A.I. Elagin, it was previously owned by P.P. Zabolotsky, and before him, I.M. Glinsky owned it [60]. Probably, Prince I.M. Glinsky was granted with an estate after his father, boyar Prince M.V. Glinsky, who distinguished himself in military service in Pskov land during the early part of the Livonian War, or, more likely, received it for his own services in the Northwest [18, p. 27; 55, p. 17; 56, p. 303, 322]. In view of relative ease of Pskov accession to Moscow and the use of already existing Novgorod experience in the development of new territories there was no need for generous distributions of the Pskov lands to the Moscow nobility. As for the Novgorod settlers, their transition to the Pskov service corporation was evidently accompanied by the loss of estates in the Novgorod district.

For example, a “tysyachnik” from the Shelonskaya fifth (Pyatina) D.A. Volokhov in 1551 was transferred to an estate in the Pskov district and as a result his possessions in the Lositsky, Bystreevsky and Belsky churchyards (pogost’’s) of the Shelonskaya fifth (Pyatina) (38 obezh (obzha) of land) were signed away to the Tsar [51, p. 69–70]. Consequently, the service as part of Pskov service town, upwards 1510, was closely connected with the land assignment of the boyar children in Pskov Uyezd. The social status of the Pskov landowners in the first third of the XVIth century was not high and was noticeably inferior to that of the Novgorod boyar children. Pskovians later Novgorodians were included in the composition of the Grand Duke’s court. There is nothing known about Pskov landowners service at court before 1550s. The first experience of large-scale involvement of Pskovians for an allRussian military event outside their area of residence took place in November 1549 during the campaign of Ivan IV to Kazan (the position of assembly of Pskov warriors was Pereyaslavl) [57, p. 365–366]. By the middle of the XVI the local landowners were divided into courtyards (“dvorovye”) (higher rank) and gorodovye service people (less noble landowners). As a result of the Thousand reform of 1550 part of the courtyard (“dvorovye”) and some families of the city boyar children of Pskov lands (for example, the Khvostovs) were made into a new rank of elected nobles and incorporated into the structure of the capital court [27, p. 220–222, 228–229].

The lower level of the Sovereign court of Vasily III was represented by the clerks. In connection with the expansion of the country’s territory, the increase and complexity of the functions of the state machine their number has increased from approximately 62 to 89 clerks [62, p. 266–268; 27, p. 387–388, 411–414]. The composition of the Chancellery has changed markedly in comparison with the reign of Ivan III. From the previous clerks there was only one fourth: V. Artemiev, I.V. Voksherin, M.V. Gorin, E. Davydov, V.V. Dolmatov, A.L. Zhertsev, V. Zhuk, D.K. Mamyrev, N.S. and T.S. Moklokovs, A.I. Nikitin, B. Paiusov, S.L. Plemyannikov, K.V. Putilov, E. Sukov, I.I. Teleshev. Some of the clerks of Ivan III took root and left their sons and relatives in the clerks: F.G. Borodaty (a relative of S.V. Borodaty), G.Z. Gnilievsky (son of Z.M. Gavinsky), A.F. Kuritsyn (son F.V. Kuritsyn), A.S. Moklokov (brother of T.S. Moklokov). Gradually, the hereditary service of clerks was gaining momentum with whole “dynasties”, which speaks of the growing prestige of service in the Grand Duke’s Chancellery. For the first time an appointment to clerks obtained V.S. and I.V. Argamakovs, M.F. and I.M. Karacharovs, T.G., I.T. and D.G. Klobukovs, A.V. and I.P. Kurtsevs, F.M. and Yu.F. Lelechins, V.M., O.M., I.M. Mishurins, S.L. and V.S. Plemyannikovs, S.N. and G.N. Plemyannikovs, I.M. and M.M. Rakovs. On clerk service were enlisted V.M. Priklonsky, D.K. Miloslavsky, V.N. Tarakanov, E.I. Tsiplyatev [62, p. 278, 290–292; 19, p. 374–377]. According to the observations of A.Yu. Savosichev, out of the 52 clerks of Vasily III, whose social background can be deduced, the majority of clerks (37 persons) came from the nobility, 8 persons were from hereditary “departmental people” (“prikaznye”), 6 from “democraticsocial groups”, one came from a merchant family. In comparison with the rule of

Ivan III, the number of hereditary “departmental people” (“prikaznye”) increased almost three-fold. However, as in the end of the XVth and the beginning of the XVIth century, representatives of provincial service families mainly served as clerks [62, p. 293].

A special issue, recently provoked by the lively interest of specialists, is connected with clerk’s monograms. This source-study plot was considered in the works of Yu.G. Alekseev, L.V. Moshkova and A.L. Gryaznov [3, p. 181–264, 300–315; 37; 21; 22]. In light of recent researchs, it became obvious that the names of the clerks are encoded in monograms and therefore they cannot be considered as abstract graphic signs. According to L.V. Moshkova and A.L. Gryaznov, the monograms performed several functions: 1) personification (evident not for everyone) of an anonymous princely signature; 2) additional protection of the document against forgery; 3) hidden communication between clerks [21, p. 24].

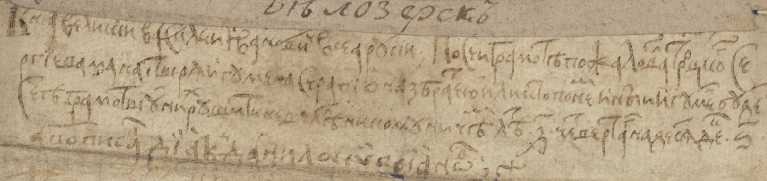

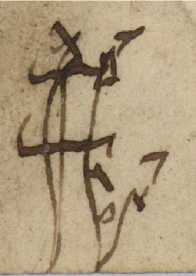

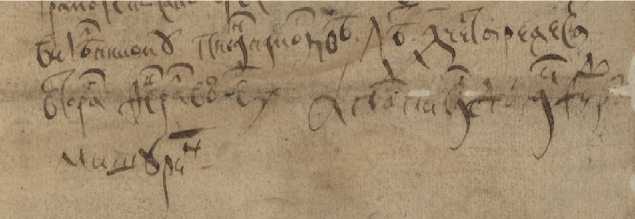

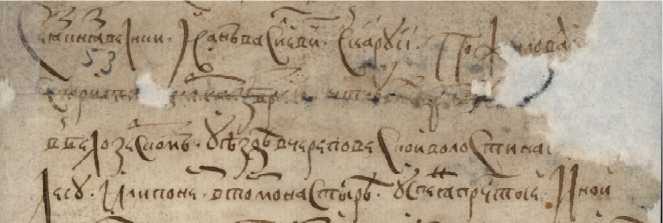

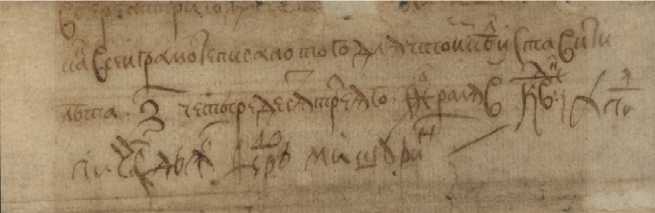

During the great reign of Ivan III, took place the formation and development of state records management and under Vasily III this process was further developed. Here should be noted some significant changes that took place at that time. According to L.V. Moshkova’s observations of the act material of the XVth – first third of the XVIth century, “seals disappear with an appearance of signatures” [36, p. 13], which obviously simplified and accelerated the drafting of a document. Another innovation was the following: the clerks monograms gradually disappeared, and they were replaced by personal clerks signatures. A.L. Gryaznov believes that this innovation appeared already under Ivan III [22, p. 68] 4. Innovation was gradually introduced into the clerical duty in the late XVth – first third of the XVIth century. New clerks who were taken to the service did not leave their monograms on the acts, but subscribed, whereas the old clerks used the usual way of identifying themselves. For example, on a number of the documents of prince Yuri Ivanovich Dmitrovsky, Grand Prince Ivan III, prince Ivan Molodoy, there is a monogram of the clerk Vasily Dolmatov [21, p. 18–19]. He continued his service in the clerks of the Grand Duke Vasily III. The charter of Ivan III to the Trinity-Sergius monastery, issued in 1486, was confirmed by Vasily III and signed by the Grand Duke’s clerk Danil Kipriyanov in 1531 (Fig. 1) [59]. As against of Kipriyanov, Fyodor Ostafiev, son of Sytin, the clerk of Prince Yury Ivanovich Dmitrovsky, used his monogram during the whole of his service in the late XVth – early XVIth centuries, which is now deciphered (Fig. 2) [21, p. 16–17; 1, p. 80; 2, p. 12]. Mikula Alexandrovich Voronin, the clerk of prince Ivan Borisovich Ruzsky, and then, after his death

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

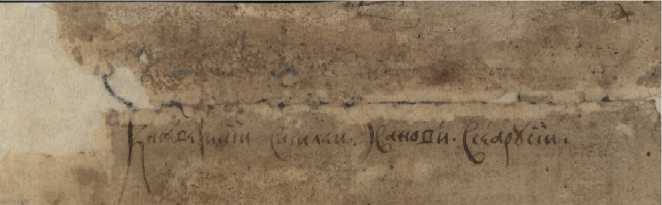

in 1503, the clerk of prince Fedor Borisovich Volotsky, also at the end of the XVth – beginning of XVIth centuries used a monogram (Fig. 3) [69; 21, p. 15–16].

Ivan Tsypla – the clerk of the Grand Duke Ivan III. His monogram occurs more than 10 times in Belozerskie acts. Return thanks to the fact that he left his signature on the charter to the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, the monogram is now deciphered [21, p. 11–12]. The son of this clerk, Tsiplyatev Elizar Ivanov’s son (1492–1546/ 47), used another method of certifying acts – he put his signature [23] 5. Consequently the change of generations in this clerks birth has coincided with the change in the records management tradition.

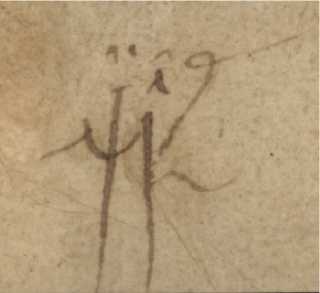

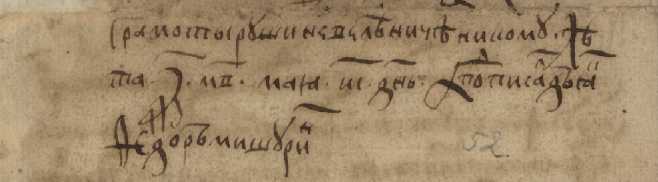

The clerk of Vasily III Fedor Mishurin is not exactly unknown [33; 63]. Let’s give some variants of his signature. In 1521, a letter was issued on the non-borrowing of chief-rent (obrok) from the mowing of the Savior-Prilutsk Monastery, which was confirmed on behalf of Ivan IV by Fedor Mishurin on February 5, 1534 (Fig. 4) [14]. In 1529, on behalf of the Grand Duke Ivan Vasilyevich, a charter was drawn up for the possession of the Assumption Voronin poustinia in the Cherepovets Volost (Fig. 5) [15]. At the same time on the back of the document is the signature of the Grand Duke Vasily Ivanovich (Fig. 6). Whether this certificate is genuine or it is a result of the activity of F.M. Mishurin, who subscribed to it on May 18, 1534, remains to be

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

seen (Fig. 7). In 1531 Vasily III released the Pechersky Ascension Monastery from the collection of duties from the monastic estate in the Nizhny Novgorod and Suzdal districts (uyezds) for 3 years. The document about this was confirmed on behalf of Ivan IV on February 22, 1535 by F. M. Mishurin (Fig. 8) [16].

If in the middle of XV century to determine the person of the clerk and, accordingly, his authority, it was necessary to know the various monograms [22, p. 69], then at the end of the XVth– first third of the XVIth century, in connection with the increase in document circulation, bureaucratization of management, the increase in the number of the departmental machinery, it was necessary to replace the old method of clerk identification on his personal signature. This was one of the consequences of the process of depersonalization and unification of records management.

Historical-genealogical analysis of the personal composition of Vasily III court showed that the core of the Sovereign court of the first third of the XVIth century was represented by those aristocratic surnames, who served to Ivan III. Of the new births in the capital were mostly immigrants from Lithuania. Their depatures took place against the backdrop of the Russian war for Smolensk and did not cease after 1514. The court of Vasily Ivanovich turned into a closed institute, access to which for not of noble birth people was significantly limited. One of the important sources for replenishing the lower level of the court with new people was the service in clerks. During the reign of Vasily III, a trend that was clearly manifested at the end of the XVth century, when the sons of the clerks were enlisted in the ranks of the boyar children of the Moscow court, was fixed.

NOTES

1 The work was prepared with the financial support of the grant of the President of the Russian Federation MK-99.2017.6.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

-

2 It is difficult to establish the origin of S.A. Volzhin, K. Gubcov, A. Ergol’skij, Ja. Ivashencev, Ja. Idolov, A. Kudrin, B. Kuchukov, L. Laptev, N. Neupokoev, P. Osjutin, I. Pirjutin, V. Polukarpov, U. Rykachev, I. Rjazanov, Ju. Sakulin, F.G. Svin’in, A. Semichev, D. Sobaka, G. Sokurov, I.Ja. Hohlov, A. Churin, P.S. Jakovcov from all household servants (“dvorovye”) of Vasily III.

-

3 The authors cordially thank M.M. Bentsianov, who kindly provided information on the land belonging to the Pskov settlers.

-

4 The authors cordially thank A.L. Gryaznov, who kindly provided information about clerks monograms.

-

5 His signature as witness (“posluch”) in 1507 аvailable at: OR RGB [Department of Manuscripts of the Russian State Library]. F. 303. Inv. 1.Unit. 244. L. 1. URL: manuscript=244.

Список литературы Sovereign court of Vasily III: historical and genealogical research

- Akty Russkogo gosydarstva. 1505-1526 . Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1975. 436 p.

- Akty Troitskogo Kalyazina monastyrya XVI v. . Moscow; Saint Petersburg, Alyans-Arheo Publ., 2007. 248 p.

- Alekseev Yu.G. U kormila Rossiyskogo gosudarstva. Ocherk razvitiya apparata upravlenija XIV-XV vv. . Saint Petersburg, St. Petersburg State University Publ., 1998. 347 p.

- Antonov A.V., ed. Pamyatniki istorii russkogo sluzhilogo sosloviya . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2011. 558 p.

- Antonov A.V., Krom M.M. Spiski russkikh plennykh v Litve pervoy poloviny XVI veka . Arkhiv russkoy istorii . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2002, iss. 7, рp. 149-196.

- Arakcheev V.A. Srednevekovyy Pskov. Vlast, obshchestvo, povsednevnaya zhizn v XV-XVII vekakh . Pskov, Pskovskaya oblastnaya Tip., 2004. 357 p.

- Arakcheev V.A. Vlast i «zemlYa». Pravitelstvennaja politika v otnoshenii tyaglyh sosloviy v Rossii vtoroy poloviny XVI -nachala XVII veka . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2014. 512 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 1999, vol. 1. 432 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Saint Petersburg, Dmitrii Bulanin Publ., 1999, vol. 2. 364 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2001, vol. 3. 304 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2004. vol. 4. 866 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2004, vol. 5. 512 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Pistsovye knigi Novgorodskoy zemli . Moscow, Pamyatniki istoricheskoy mysli Publ., 2009, vol. 6. 382 p.

- Baranov K.V., ed. Katalog pistsovykh opisaniy Russkogo gosudarstva serediny XV -nachala XVII veka . Moscow, Drevlehranilishe Publ., 2015. 124 p.

- Bentsianov M.M. «Lishnie lyudi»: rotatsiya sostava Gosudareva dvora v Russkom gosudarstve v kontse XV -seredine XVI v. . Drevnyaya Rus. Voprosy medievistiki , 2017, no. 1 (67), pp. 35-48.

- Bychkova M.E. Rodoslovie knyazey Glinskikh . Istoricheskaya genealogiya , 1994, no. 3, рp. 25-27.

- Chechenkov P.V. Mezhpokolennaya kommunikatsiya: rodovaya pamyat nizhegorodskogo dvoryanstva XVII veka . Aktualnye problemy sotsialnoy kommunikacii: materialy vtoroy Mezhdunarodnoy nauchno-prakticheskoy konferentsii . Nizhniy Novgorod, Nizhegorodskiy gosudarstvennyy tekhnicheskiy universitet im. R.E. Alekseeva, 2011, pp. 374-377.

- Filyushkin A.I. Vasily III. Moscow, Molodaya gvardiya Publ., 2010. 346 p.

- Gnevushev A.M., ed. Pistsovaya kniga Vodskoy pyatiny 1540 g. . Novgorod, Tip. Novgorodskaya uchenaya arkhivnaya komissiya, 1917. 304 p.

- Grjaznov A.L. Dyacheskie monogrammy na aktakh iz fondov GKE . Vestnik "Aljans-Arheo" . Moscow; Saint Petersburg, 2017, iss. 18, pp. 31-84.

- Grjaznov A.L., Moshkova L.V. Principy chteniya dyacheskih monogramm na aktah XV -nachala XVI v. . Vestnik Vestnik "Aljans-Arheo" . Moscow; Saint Petersburg, 2017, iss. 19, pp. 3-24.

- Kobrin V.B. Oprichnina. Genealogiya. Antroponimika. Izbrannye trudy . Moscow, Rossiskiy gosudarstvennyy gumanitarnyy universitet Publ., 2008. 369 p.

- Korzinin A.L. Gosudarev dvor Ivana III . Drevnyaya Rus: vo vremeni, v lichnostyakh, v ideyakh. Almanakh. Vyp. 7 (K 60-letiyu professora A. Yu. Dvornichenko) . Saint Petersburg, 2017, pp. 134-150.

- Korzinin A.L. Gosudarev dvor Russkogo gosudarstva v dooprichnyy period (1550-1565 gg.) . Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Alyans-Arkheo Publ., 2017. 672 p.

- Korzinin A.L. Knyazheskaya aristokratiya pod Novgorodom v kontse XV -nachale XVI v. Prichiny utraty znatyu Novgorodskikh zemel . Trudy kafedry Istorii Rossii s drevneyshikh vremen do XX veka . Saint Petersburg, 2006, vol. 1, pp. 388-410.

- Korzinin A.L. Pivov Roman Mikhaylovich. Bolshaya Rossiyskaya entsiklopediya . Moscow, Bolshaya Rossiyskaya entsiklopediya Publ., 2014, vol. 26, pp. 169-170.

- Korzinin A.L., Shtykov N.V. Sostav Boyarskoy dumy i dvortsovykh chinov v knyazhenie Vasiliya III . Bylye gody , vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 330-341.

- Krom M.M. Mezh Rusyu i Litvoy. Pogranichnye zemli v sisteme russko-litovskikh otnosheniy kontsa XV -pervoy treti XVI v. . Moscow, Kvadriga Publ., 2010. 320 p.

- Krom M.M., ed. Radzivillovskie akty iz sobraniya Rossiyskoy natsionalnoy biblioteki. Pervaya polovina XVI v. . Pamyatniki istorii Vostochnoy Evropy . Moscow; Warsaw, 2002, vol. 6. 267 p.

- Kupchaya gramota na pokupku dereven I.D. Bobrovym u brata V.D. Bobrova. 1507 g. . Otdel rukopisey Rossiskoy gosydarstvennoy biblioteki , F. 303, Inv. 1, no. 244, p. 1.

- Maslennikova N.N. Prisoedinenie Pskova k Russkomu tsentralizovannomu gosudarstvu . Leningrad, Leningradskiy gosudarstvennyy universistet Publ., 1955. 196 p.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoy Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 79/3, p. 9.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 105, pр. 168, 166, 184.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 106. p. 230.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 108, p. 206.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 109, pр. 6, 14, 102.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 112, L. 96, рp. 116, 161.

- Materialy dlya rodosloviy. Nachalo XX veka . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 131, Inv. 1, no. 113, p. 114.

- Mazurov A.B. Rod dyakov Mishurinykh v XVI v. . Rossiyskaya istoriya , 2013, no. 5, pp. 105-110.

- Morozova L.E. Brachnaya politika Vasiliya III . Drevnyaya Rus: vo vremeni, v lichnostyakh, v ideyakh. Almanakh. Vyp. 7 (K 60-letiyu professora A. Yu. Dvornichenko) . Saint Petersburg, 2017, pp. 200-224.

- Morozova L.E. K voprosu ob obstoyatelstvakh zhenitby Vasiliya III na Solomonii Saburovoy . Vestnik Leningradskogo universiteta im. A. S. Pushkina , 2014, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 156-167.

- Moshkova L.V. Gramoty XV -pervoy treti XVI v. iz f. 281 RGADA: paleograficheskie zametki (Statya pervaya) . Vestnik "Aljans-Arheo" . Moscow; Saint Petersburg, 2016, iss. 17, pp. 40-89.

- Moshkova L.V. Rukoprikladstva na gramotakh XV -pervoy treti XVI v. (predvaritelnye nablyudeniya) . Otechestvennye arkhivy , 2015, no. 4, pp. 12-19.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. Bezobrazova i komp., 1859. vol. 1. 461 p.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. Bezobrazova i komp, 1862, vol. 2. 890 p.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. Bezobrazova i komp, 1868. vol. 3. 960 p.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. ministerstva Vnutrennih del, 1886, vol. 4. 584 p.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. Senata, 1905, vol. 5. 696 p.

- Novgorodskie pistsovye knigi . Saint Petersburg, Tip. Senata, 1910, vol. 6. 1074 p.

- Pistsovaya (platezhnaya) kniga Pskovskogo uezda 1585 g. Kopiya XVIII v. . Rossiyskiy gosydarstvennyy arkhiv drevnikh aktov . F. 1209, Inv. 1, Book 827.

- Pistsovaya (platezhnaya) kniga Pskovskogo uezda 1585 g. Kopiya XVIII v. . Rossiyskiy gosydarstvennyy arkhiv drevnikh aktov , F. 1209, Inv. 1, Book. 827, p. 81 reverse.

- Pistsovaya kniga pomestnykh zemel poloviny Vodskoy pyatiny: pisma G.M. Valueva 1538/39 g. . Rossiyskiy gosydarstvennyy arkhiv drevnikh aktov , F. 1209, Inv. 3, no. 17145, pp. 1-207.

- Pistsovaya kniga Vodskoy pyatiny: pisma S.I. Klushina i S. Ryazanova 1538/39 g. . Rossiyskiy gosydarstvennyy arkhiv drevnikh aktov , F. 137, no. 5.

- Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisey . Moscow, Yazyki russkoy kultury Publ., 2003, vol. 5, iss. 1. 256 p.

- Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisey . Moscow, Yazyki russkoy kultury Publ., 2000, vol. 5, iss. 2. 368 p.

- Razryadnaya kniga 1475-1605 gg. . Moscow, Institut istorii Akademii nauk SSSR Publ., 1981, vol. 2, no. 1. 219 p.

- Razryadnaya kniga 1475-1605 gg. . Moscow, Institut istorii Akademii nauk SSSR Publ., 1980, vol. 2, no. 2. 440 p.

- Razryadnaya kniga 1475-1605 gg. . Moscow, Nauka Publ., 1977, vol. 1, no. 2. 612 p.

- Savosichev A.Yu. Dyak Fedor Mishurin: Sudba prikaznogo byurokrata XVI v. . Vestnik RUDN. Seriya Istoriya Rossii , 2009, no. 3, pp. 76-87.

- Savosichev A.Yu. Dyaki i podyachie XIV-pervoy treti XVI vv.: proiskhozhdenie i sotsialnye svyazi. Opyt prosopograficheskogo issledovaniya . Orel, Orlovskiy gosudarstvennyy universitet Publ., 2013. 519 p.

- Sbornik Moskovskogo arkhiva Ministerstva yustitsii . Moscow, Tip. A. Snegirevoy, 1915, iss. 5. 520 p.

- Sbornik Russkogo istoricheskogo obshchestva . Saint Petersburg, Tip. F. Eleonskogo i K., 1887, vol. 53. 252 p.

- Stanislavskiy A.L. Trudy po istorii gosudareva dvora v Rossii XVI-XVII vekov . Мosсow, Rossiyskiy gosudarstvennyy gumanitarnyy universitet Publ., 2004. 506 p.

- Zhalovannaya gramota kn. I. B. Ruzskogo Simonovu monastyrju 1495 g. . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk , F. 41, no. 38.

- Zhalovannaya gramota velikogo knyazya Ivana Vasilyevicha Troice-Sergievu monastyru. 17 avgusta 1486 g. . Rossiyskiy gosydarstvennyy arkhiv drevnikh aktov , F. 281, no. 864.

- Zhalovannaya gramota velikogo knyazya Vasiliya Ivanovicha na Vologdu. 18 fevralya 1521 g. . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoy Akademii nauk , F. 41, no. 48.

- Zhalovannaya gramota velikogo knyazya Vasiliya Ivanovicha Pecherskomu Nigegorodskomu monastyru. 19 sentebrya 1531 g. . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk . F. 41, no. 54.

- Zhalovannaya gramota velikogo knyazya Vasiliya Ivanovicha Uspenskoy Voroninoy pustyni. 20 yanvarya 1529 g. . Arkhiv Sankt-Peterburgskogo instituta istorii Rossiyskoi Akademii nauk . F. 41, no. 53.

- Zimin A.A. Formirovanie boyarskoy aristokratii v Rossii vo vtoroy polovine XV -pervoy treti XVI v. . Мoscow, Nauka Publ., 1988. 356 p.

- Zimin A.A. Novoe o vosstanii Mihaila Glinskogo v 1508 g. . Sovetskie arkhivy , 1970, no. 5, pp. 68-73.

- Zimin A.A. Rossiya na poroge Novogo vremeni (Ocherki politicheskoy istorii Rossii pervoy treti XVI v.) . Moscow, Mysl Publ., 1972. 452 p.

- Zimin A.A., ed. Tysyachnaya kniga 1550 g. i Dvorovaya tetrad 50-kh godov XVI v. . Мosсow; Leningrad, Academiya nauk SSSR Publ., 1950. 454 p.