Specificity of socio-economic processes in the Hungarian microregion

Автор: Krsz Katalin

Журнал: Региональная экономика. Юг России @re-volsu

Рубрика: Фундаментальные исследования пространственной экономики

Статья в выпуске: 4 т.9, 2021 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The Kunhegyesi District is the most disadvantaged district in the Northern Great Plain Region of Hungary. The aim of this study, which serves as a basis for a social comparative analysis of the District’s settlements in the future, is to understand the demographic processes. Population in the District has been steadily decreasing since 2011 besides lower income levels, poorer health indicators and a higher proportion of premature mortality. Two out of three children are disadvantaged, while the vast majorityof young people drops out of secondaryschool without any qualification. The higher-than-average proportion of Roma population alone does not explain worsening economic output, economic performance has nothing to do with ethnic origin. Reasons are rather to be found in the deterioration of social mobility of the past two decades. Similarly to areas with a higher proportion of Roma population, the District also undergoes an exodus of non- Roma, resulting in ghettoization, thereby further diminishing chances of social mobility. Thanks to social inclusion and recovery programs, as well as the commitment of local Roma stakeholders, promising changes are coming true with an increase in qualification and employment levels and a decrease in the number of disadvantaged children, question is whether development is sustainable in the long run, and also, whether the District has a potential to independently self- sustain social development.

Demography, social inclusion, disadvantage, social services, child poverty, social support, economic development, roma, social mobility

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/149139604

IDR: 149139604 | УДК: 332.02 | DOI: 10.15688/re.volsu.2021.4.10

Текст научной статьи Specificity of socio-economic processes in the Hungarian microregion

DOI:

Social issues stemming from the specificity of rural life are richly featured in academic literature (see e.g. [Molnár, Bodási, 2016; Ritter, 2018]). Social issues are either the main cause, or the consequence of disadvantaged situation, and therefore hinder the potential for economic development of the affected regions (see e.g. [Jedynak, Káposzta, Kinal, 2017; Ritter, 2017]). Understanding the nature of social issues, unfolding and addressing them are a prerequisite for regional development, according to academic sources (see [Kirby, 2006; Ritter, 2014]).

Hungary, bordered by Austria on the West, followed clockwise by Slovakia on the North, Ukraine on the Northeast, Romania on the East, Serbia and Croatia on the South, and Slovenia on the Southwest, is located in the Carpathian Basin in Central Europe. Spanning across 93,030 square kilometres, Hungary is a medium sized European Union member state with 9.8 million inhabitants. For administrational and statistical purposes, Hungary is officially divided into 7 statistical regions, which are subdivided into 19 counties (megye, in Hungarian) and 174 districts (járás, in Hungarian), 6–18 districts per county, based on Act No. XCIII of 2012 on the classification of districts, and Act XCII of 1999 amending Act XXI of 1996 on the Regions. Districts consist of a varying number settlements, each governed by a municipality, headed by a directly elected mayor and a body of local representatives.

The Kunhegyesi District of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, is the most disadvantaged district of the North Great Plain Region. Current study scrutinises the social and demographic processes in the district. The study shall be followed by further primary and secondary research on the availability and accessibility of social services, institutions and infrastructure, so that the compiled results can serve as basis for a comparative analysis of the local administrative units (i.e. settlements) located in the district, with a focus on tendencies of social development and social inclusion.

This study is primarily focused on people living in poverty, including Roma communities, members of the largest ethnic minority of Hungary, and secondarily on other vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, women, and children. Findings shall contribute to a more comprehensive research in which chances for social inclusion vs. risks of impoverishment are estimated and compared amongst the settlements of the district, and weighed against other settlements in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County. Understanding the fluidity of social mobility is rather subjective and varies from one community to the other, from one household to the other, as well as from on individual to the other, not to mention the variability over time, in a constantly volatile environment. It is nevertheless possible to calculate social mobility prospects by use of absolute and relative mobility calculations [Huszár, Záhonyi, 2018], and, considering the critiques of the methodology [Harcsa, 2018], shall be further tuned with results of a primary survey. The comprehensive research shall be based on the following data and information:

Demographic processes in Kunhegyesi District: population structure, with special attention to changes in the number of poor people living on the periphery of settlements, slums or segregated areas, among them primarily, but not exclusively ethnic Roma; changes over time in income and wealth, employment and education attainment levels; data and trends regarding children and child poverty, academic performance, and proportion of disadvantaged and at-risk children; claims for extraordinary subsidies and social support; health data on mortality and preventable early deaths; and, correlation, if any, between socio-economic situation and the ethnic composition of the population – all of which are the subject matter of the current study;

– Police and law enforcement statistics on petty theft, violent crimes, crime against property, domestic violence, child abuse, drug abuse;

– Number, value and effectivity of drawn and/ or implemented EU funded projects for the promotion of social inclusion of the 2014–20 budgetary period, as well as subjective perceivability thereof at community and individual levels;

– Availability and accessibility of social care facilities and personnel; availability and accessibility of public services and infrastructure.

The available infrastructure, as well as the lack of public services shall be mapped graphically, along with the population’s perceived accessibility to them. The findings of the research shall allow the revelation of shortages and lack of accessibility to local and regional public services, with a focus on people living in poverty, Roma communities, the elderly, women, and children, and thereby may contribute to defining future development goals more precisely for decision-makers.

The current study is therefore an initial socialdemographic analysis preceding a more comprehensive research, which aims to compare chances for social mobility among the settlements of Kunhegyesi District.

Methodology

Kunhegyesi District (hereinafter referred to as the District, unless otherwise indicated), which consists of seven settlements, is the most disadvantaged district of the Northern Great Plain Region and ranks fifth among the poorest in the whole of Hungary. Three out of seven settlements are affected by significant unemployment, while two of its settlements, Tiszabő and Tiszabura, target localities of a number of EU funded and domestic development programs, NGOs and religious charity organisations, produce some of the most extreme economic and social data in the whole county. Despite the amount of development funds and hence some favourable tendencies, the region seems unable to leverage a meaningful and self-sustaining development [Havasi, 2015].

In the current study, secondary economic data with regards to composition and demographic trends of the local population, income levels and wealth, education, employment and health are analysed, along with data on children, academic performance, child poverty, proportion of disadvantaged and at-risk children, data on claims for extraordinary subsidies and social support, such as social subsidies, firewood support, job-seekers’ allowances, child protection support, housing allowance, etc. The change over time in the number of local or nearby job vacancies, including those offered by recently founded social enterprises and cooperatives for economic development, some of which were state-financed, will also be an important indicator. Finally, data on children and child poverty will be analysed.

Based on Act No. 125 of 2003 on Equal Opportunities and the Promotion of Equal Treatment, all settlements are obliged to dispose of a Local Equal Opportunities Programme (hereinafter referred to as HEP, after its Hungarian abbreviation). The HEPs are prepared by the competent local officials and adopted by the local council, to be renewed every five years and revised biannually, in which all data regarding equal opportunities, vulnerable groups and local particularities are collected and analysed, social deficiencies and possible causes are identified and, based on them, an action plan is implemented. The HEPs, of which a secondary research and analysis is carried out, are the most important and reliable source of information on social issues and shortages of public services, even though the subjective evaluation of the authors may somewhat distort emphases.

Besides an analysis of the deficiencies in public services identified in the HEPs of all the localities in the District, in order to find out what could contribute to fostering favourable social tendencies other that external financial resources, an online survey was conducted with the mayors of the municipalities of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County in the first quarter of 2020, which focussed on a variety of topics, including shortages of and lack of accessibility to public services, from the estimated number of Roma and people in poverty, to housing, to how the development funds of the 2013–2020 budgetary period have been leveraged, etc. Sixty-four replies were submitted out of the seventy-eight in the county, and five out of the seven in the district. Based on the replies, as well as interviews with local decision makers, the following findings were made.

Furthermore, the contents of the minutes taken at the regular County Social Forums organised by the Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County Municipality four times since 2018 October until their temporary suspension due to the pandemic, provide a closer and more pragmatic insight into which issues to address. The Forum is a meeting place for local stakeholders, civil society leaders for vulnerable communities, minority self-government representatives and social workers where they can exchange views and harmonise goals along the key guideline of the Hungarian National Social Inclusion Strategy 2011– 2030, that is “Nothing about Us without Us”. The Forum also facilitated the creation and meetings of the County Working Groups for the target groups.

Results

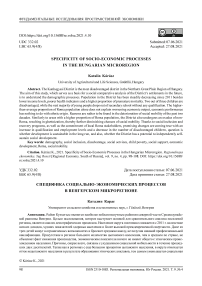

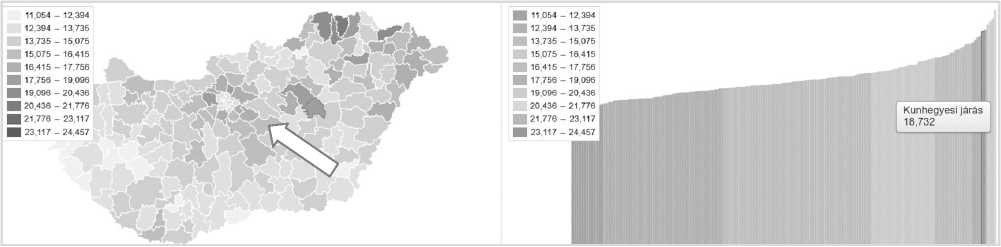

The Kunhegyesi District is located in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County in the North Great Plain

Region (NUTS2) of Hungary (see Figure 1), and lies East of River Tisza and South of Lake Tisza in the historical and geographic region of Nagykunság. It is the most disadvantaged district of the North Great Plain Region. Within its territory of 465 km2 it comprises seven settlements with a total population of 20,074 as of 2018, among them two towns, Kunhegyes with 7,660 inhabitants, and Abádszalók (4,129), as well as five villages, Tiszabura (2,929), Tiszabő (2,117), Tiszaroff (1,535), Tiszagyenda (958), and Tomajmonostora (746) [TeIR, 2018]. The district capital, Kunhegyes, lies in the Southernmost corner of the District and is located at 10 to 23 km from the rest of the settlements.

The Kunhegyesi District is the most disadvantaged district in the Northern Great Plain Region. The District is to be developed with complex programmes based on Government Decree No. 290/2014 (November 26) on the Classification of Beneficiary Districts. The majority of settlements, five out of seven, are entitled to be beneficiaries of economic, social and infrastructural developments, based on Government Decree No. 105/2015 (April 23) on the Classification of Beneficiary Settlements and the Conditionality of Benefits.

The population of Kunhegyesi District have been steadily decreasing since 2011. As indicated before, two settlements of the District, Tiszabő and Tiszabura are among the poorest settlements of Hungary according to statistical data. The annual average net per capita income in the Kunhegyesi District was 628,695 HUF (see Table 1), which makes it the poorest district of the nine in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County.

Fig. 1. The location of Kunhegyesi District in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County in the North Great Plain Region in Hungary

Note. Source. Own edition.

Table 1

Average Annual Net Per Capita Income in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, 2018 (HUF)

|

District of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County |

Annual Net Per Capita Income (HUF) |

|

Szolnoki District |

1,109,526 |

|

Jászberényi District |

1,062,913 |

|

Törökszentmiklósi District |

873,218 |

|

Mezőtúri District |

858,698 |

|

Karcagi District |

823,765 |

|

Jászapáti District |

811,034 |

|

Kunszentmártoni District |

805,885 |

|

Tiszafüredi District |

798,111 |

|

Kunhegyesi District |

628,695 |

Note. Source. Own edition based on TeIR data, 2020.

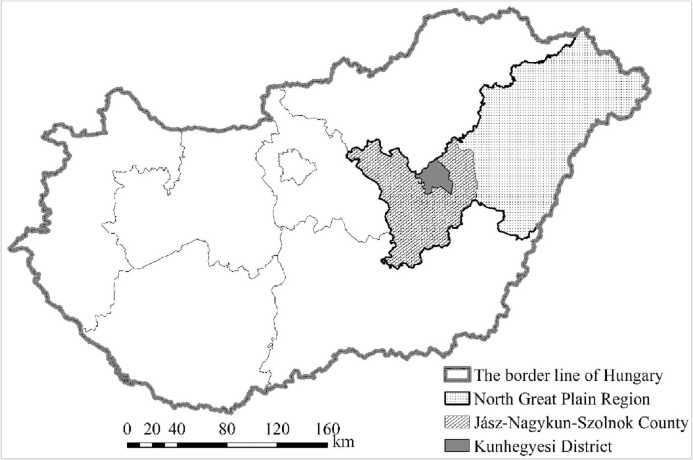

The decreasing population count is due both to a negative reproduction rate, and a constant negative migration balance, that is the difference between the number of new settlers versus the number of movers, year after year (see Figure 2).

What makes the population of Kunhegyesi District want to leave in search of a better living? The county social inclusion forums have revealed that the number of children per household is higher than average, the number of children removed from their families is high [Szurovec, 2019], job opportunities in the primary labour market are scarce, education levels are lower, drug abuse is severely widespread, and the number of domestic violence reports is higher than average, most probably aggravated by the lockdowns as a result of the pandemic. It is also important to examine and understand the age structure of the society of the District.

The proportion of minors aged 0–2 years steadily grew between 2012 and 2017 and has somewhat decreased since, and showed a figure of 4.1% in 2018. The number of toddlers per accessible day care service is 15. However, only 52 toddlers were enrolled while day care capacity for available for 55 (TeIR), which means that capacities currently exceed the demand for day care. Should the demand significantly increase in the future, for example because more young mothers have access to employment and would wish to seek day care for their children, capacity will not be sufficient. Day care for children aged 0–2 years not only ensures regular nutritious alimentation but also encourages parents to seek training or employment during the day. The EU funded Regional and Urban Development Programme (TOP) made possible the establishment or expansion of four day care centres in Kunhegyes, Tiszabő, Tiszabura and Tomajmonostora.

The number of children aged 3–5 years enrolled in compulsory kindergarten care was 959 in 2018. The lowest figure, 743, was in 2015, which follows the 2012 lowest of the toddlers. The kindergarten capacity somewhat exceeds the total number of children, so all children have access to the compulsory kindergarten service. The proportion of disadvantaged children is 67.65%, the highest in the North Great Plain Region (KSH, TeIR).

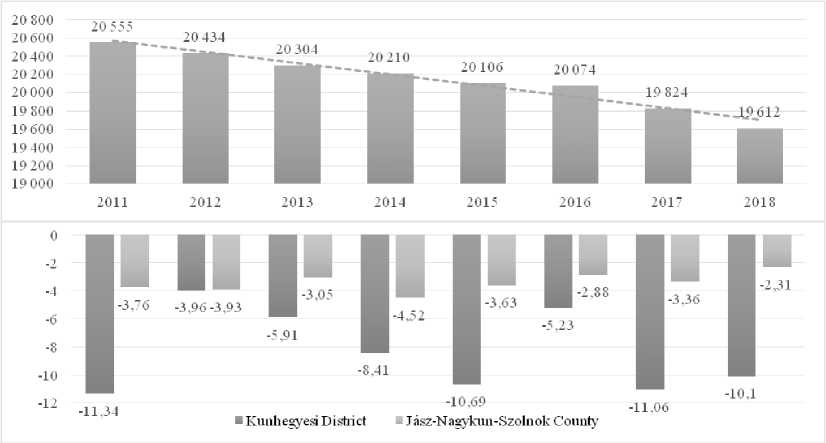

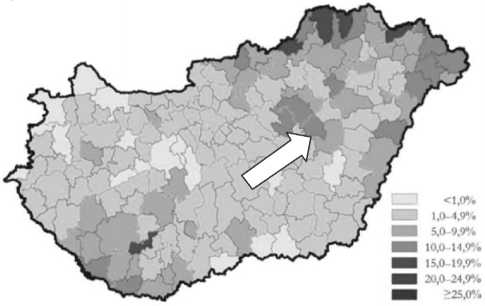

There are 11 primary schools in the District. The number of children enrolled in primary schools was 2,025 in 2018. The proportion of disadvantaged children is 66.81%, an alarming nearly five times the national average and more than twice the county and the regional average. The total proportion of children aged 0–14 compared to the whole population is significantly higher than that of the county, regional or national figures. Actually, this proportion is the highest in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County as well as the Northern Great Plain Region, while it is it is one of the highest countrywide, only exceeded by the three poorest districts of Northern Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County (see Figure 3).

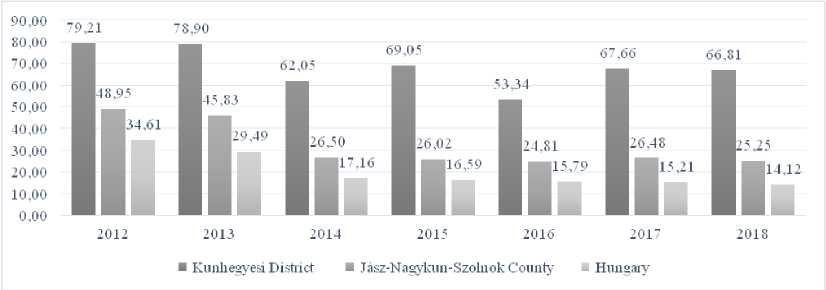

The proportion of children of 0–14 years is significantly higher than the county, regional or national average (see Figure 4). It is worth mentioning that Tiszabх ranks number one in this respect amongst all the 3,155 settlements of Hungary. Out of the 175 districts of Hungary, the Kunhegyesi District is the fourth in this

Fig. 2. Population (persons) and migration balance (permille, ‰) of Kunhegyesi District, 2011–2018 Note. Source . Own edition based on TeIR data, 2020.

Fig. 3. Proportion of disadvantaged primary school aged children (percent, %) of Kunhegyesi District, 2011–2018 Note. Source . Own edition based on KSH and TeIR data, 2021.

Fig. 4. Proportion of children of 0–14 years to the total permanent population in Kunhegyesi District, 2018 (percent, %) Note. Source. Own edition based on KSH and TeIR data, 2021.

respect, only overtaken by three districts in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County along Hungary’s Northeast border line. Consequently, the proportion of the elderly is significantly lower than the national average and the lowest in the Northern Great Plain Region.

This means that the District has a fairly young population, which could as well be good news and a reason for hopes if it weren’t for one of the lowest life expectancy data countywide, the very lowest number of taxpayers per active population, the aforementioned high proportion of disadvantaged children, one of the poorest health conditions, as well as one of the lowest net per capita income besides a steadily decreasing population count.

What are the possible reasons behind the declining social and economic tendencies of the District, which makes it the poorest performing district in many aspects county-wise and regionally?

We cannot ignore the fact that the average education attainment level is also significantly lower than the national average. The number of young people is secondary education is steadily decreasing, that is, their number has decreased by 5,000 in the recent decade. A mere 17% of teenagers aged 15– 17 years attend secondary education, of which the main cause, according to the unanimous opinion of the social inclusion forum members, is the lowering of compulsory schooling age from 18 to 16 based on Act on National Public Education of 2011. As we have seem, the high proportion of children in the total population, therefore, is not a very informative data on social status in itself. However, when related to the proportion of disadvantaged and at-risk children, as well as children with special educational needs, children with impaired socialisation skills, and children removed from their family and lodged at orphanages, it provides a much more refined picture on the fact that some, if not most, of these children are being born in far less than ideal circumstances [Domonkos, 2010]. Even though it has been declared unconstitutional to remove children from their families on the motive of poverty, and it is proven that providing help to poor families to ensure appropriate circumstances for their children costs a fraction of what bringing up children in orphanages cost [Szurovec, 2019; Sofovic, Kragulj, Pop, 2012], the number of removed children because of poverty has been rising again in recent years. It is now more understandable why its inhabitants are tending to leave the district.

Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County stretches along the north of the Hungarian Great Plains where rural farmyards and homesteads are still trying to survive despite their systematic downsizing since the 1950’s. Pejorative connotation of the word peasant or farmer (paraszt or tanyasi, in Hungarian) dates back to postWorld War 2 political ideology and regional development programming [Enyedi, Tamási, 2001]. Even though countryside life is living its renaissance (see e.g. [Gonda, Péli, Nagyné, 2020]), coupled with a rediscovery of nature, an endeavour for green energy and self-sustainability for highly trained professionals and well-to-do explorers, who wish to fulfil their obligations for work by moving their home office (see in more details e.g. [Ritter, 2017]), in order for the region to become attractive for newcomers it is indispensable to improve the availability and accessibility of public services and infrastructures.

The county forum accommodated the discussion on several occasions whether there is a correlation between the proportion of ethnic Roma and the worrying socio-economic issues. Despite the sensitivity of the topic, the members openly discussed pros and cons. It was established that even though communities with a higher proportion of Roma tend to be poorer with multiple social issues, ethnic origins have nothing to do with socio-economic performance.

Examining official data, it is obvious that the proportion of self-identified Roma in Kunhegyesi District is the highest in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County. Unfortunately, the last official data, 17.93%, dates back to the 2011 census, when propensity to identify as a member of the Roma minority was already much higher than it had been during the preceding census in 2001, thanks to the Idetartozunk! (We belong here!) – Census 2011 civil campaign led by Jenх Setйt Roma civil rights activist and sponsored by the Open Society Foundation – Diverse Hungary Programme , in which Roma interviewers and influencers encouraged the Roma population to identify themselves as Roma

[Idetartozunk Egyesület ... , 2019]. As a result, the official population of Roma rose from 190 thousand in 2001 to more than 310 thousand in 2011. Still, rough expert estimates are well around at least the double of this figure [Matkovich, 2011].

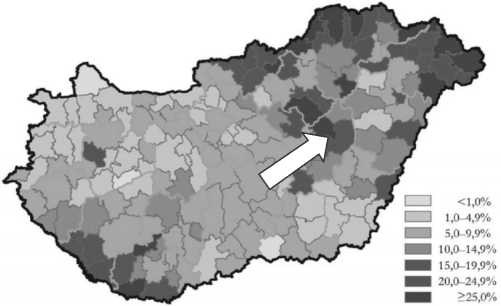

It is presumed that the data on the number of Roma people is closest to reality in the publication of the Faculty of Socio-Geography and Regional Development of the University of Debrecen (DE, after its Hungarian abbreviation), which aggregated the number of Roma population based on the so-called Gypsy Coordination Committee survey method of 1984–1987, the CIKOBI survey, after its Hungarian abbreviation, and updated to 2010–2013. The new results were based on surveying local councils and minority self-governments, besides available statistical data (see in more details in [Pénzes, Tátrai, Pásztor, 2018]). Figure 5 shows the difference in the proportion of Roma in 1984–1987, compared to their proportion in 2010–2013, according to which beyond official data and self-identification, people identified as Roma by their environment based on their lifestyle, anthropological features and the nature of cohabitation, were also taken into consideration. It is obvious that Kunhegyesi District is among the highest proportion districts of Hungary, besides some others in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg and Baranya Counties.

As concluded above, ethnicity and the higher-than-average proportion of Roma is not the root cause of deteriorating economic performance. The Hungarian society used to be considered one of the most open societies during and after the political transition period of 1989–1990, with relatively well permeable social strata. Sorry to say, researches of the 2000’s have found that fluidity and permeability of the society has become rather sticky, ranking last among the neighbouring countries as regards social

Fig. 5. District-level proportion of Roma in the 1984–87 CIKOBI survey compared to the 2010–2013 DE survey Note. Source. Own edition based on: [Pénzes, Tátrai, Pásztor, 2018].

mobility [Bukodi, Paskov, Nolan, 2017], which means that once you are born poor, Hungary provides the worst chances for you to make a change in your fate in Central-Eastern Europe. Not only have the income and wealth inequalities grown in the recent decade, but also the social structures have become ever more polarised, and despite government efforts to decrease poverty by introducing the so-called work-based society and the life-long support system, the equal opportunities indicators have worsened in all respects [Huszár, Záhonyi, 2018].

The settlement structure of the Northern Great Plain Region, with rural settlement at relatively large distances from each other, may also contribute to a more difficult social mobility. Also, some patterns and traditions inherited over generations in Roma communities, the cultural backgrounds, the traditional notion of the family and gender roles might play a part in the negative tendencies in social mobility. While two generations ago the Roma population mostly tended to live in the countryside, in the recent three decades a lot of Roma moved to the larger worker-magnet cities in search for jobs, primarily the capital city of Budapest. Nevertheless, their proportions are sill the highest in rural areas in smaller settlements. In some of these localities, like in Kunhegyes District, the local society is likely to experience irreversible processes: it is obvious that the proportion of Roma became the highest in those districts where their proportions had already been higher during the CIKOBI survey of 1984–1987. The Kunhegyesi District is among the most densely populated districts when it comes to Roma, according to a variety of researches in the past decades (Table 2).

Similarly to other districts with a higher proportion of Roma population, besides a decresing total population count, the Kunhegyesi District is constantly losing a larger proportion of its non-Roma population. At the same time, the remaining non-Roma population is ageing, has a lower fertility rate and a higher first child bearing age on average, alongside a gradually growing Roma population with higher fertility rate and a lower first child bearing age. This results in a slow transformation of once diverse local communities turning into Roma majority or purely Roma communities, such as Tiszabő, Tiszabura or Tiszaroff in Kunhegyes District, which rarely bring along blossoming prosperity, but are rather likely to become slums, some of which are hotbeds for further issues, that require huge effort to turn wrong tendencies. The loss of diversity and the impossibility of integration therefore also contribute to the diminishing chances for social mobility.

The rate of young unemployed under the age of 25 is also a record high at 20.68%. The highest average proportion of ethnic Roma and people living in poverty in the District hence means that intersectionality is also predominant here, that is when race, class, gender, age, disability and/or other characteristics “intersect” with one another and overlap, thereby making the individual exposed to oppression on multiple bases. The proportion of population with maximum 8 years of primary school education is the highest in Kunhegyesi District among the all the districts, with its alarming 35% high, which is again a serious obstacle for social mobility, it is to substantially decrease with the help of future development programs and campaigns.

Of these, 25.43% do not dispose of a regular income. Furthermore, the more than half of households are without anyone employed (50.26%) [TeIR, 2018]. This depressingly high figure reflects the low average qualification levels, which further decrease the chances of employment – a vicious

Table 2

Districts with the highest proportion of Roma in Hungary, at the time of the different researches, %

|

№ |

CIKOBI, 1984–1987 |

DE, 2010–2013 |

Census, 1990 |

Census, 2011 |

||||

|

District |

% |

District |

% |

District |

% |

District |

% |

|

|

1 |

Edelényi |

17.2 |

Encsi |

39.0 |

Encsi |

11.1 |

Encsi |

23.2 |

|

2 |

Ózdi |

17.0 |

Ózdi |

37.8 |

Kunhegyesi |

10.0 |

Szikszói |

19.6 |

|

3 |

Encsi |

16.6 |

Sellyei |

35.1 |

Záhonyi |

9.3 |

Edelényi |

18.1 |

|

4 |

Cigándi |

15.1 |

Hevesi |

34.7 |

Vásárosnaményi |

9.2 |

Kunhegyesi |

17.9 |

|

5 |

Sásdi |

15.0 |

Edelényi |

33.7 |

Edelényi |

9.0 |

Cigándi |

16.5 |

|

6 |

Sellyei |

14.9 |

Bátonyterenyei |

32.5 |

Nyírbátori |

8.3 |

Sellyei |

16.1 |

|

7 |

Fehérgyarmati |

13.3 |

Cigándi |

32.4 |

Ózdi |

8.0 |

Hevesi |

14.8 |

|

8 |

Kunhegyesi |

13.3 |

Mezőcsáti |

30.3 |

Fehérgyarmati |

7.5 |

Gönci |

14.0 |

|

9 |

Mátészalkai |

13.3 |

Nyírbátori |

29.0 |

Gönci |

7.4 |

Szécsényi |

13.7 |

|

10 |

Szécsényi |

13.2 |

Sásdi |

27.9 |

Szerencsi |

7.3 |

Vásárosnaményi |

13.3 |

Note. Source: [Pénzes, Tátrai, Pásztor, 2018].

circle. The people in this stratum are those whose prospects are far the worst; they have a minimal chance to find a job, and experience shows that their living conditions are likely to predestine their descendants to struggle with very similar social issues, even though the region still provides job opportunities mainly in the traditional agricultural sector [Ritter, 2008]. It is important to examine what are their chances for a qualification and/or employment in low prestige workplaces. There are state-funded social inclusion programmes, such as that of the Maltese Charity Service in two settlements of the District, Tiszabő and Tiszabura, where, based on their so-called diagnose-based inclusion strategy, a social development programme is conducted with economic recovery initiatives and a constant personal presence of mentors [Kiss et al., 2013]. Intermediate results are promising while it is already obvious that small but tangible changes require full personal commitment and huge resources. Some have managed to find work in constructions, others undertake seasonal agricultural work in order to receive some irregular income. At the same time we should not ignore the fact that the outflow of workforce from the agriculture, due to automatization and the rapidly ageing traditional workforce, also contributes to regional inequalities [Ritter, 2008].

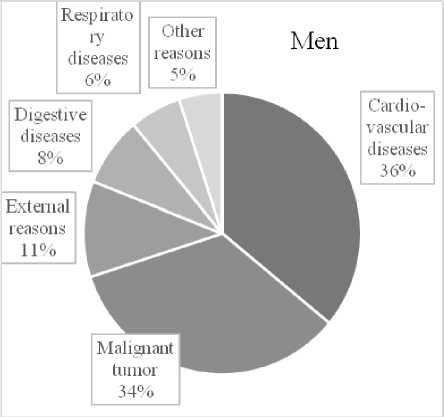

Life expectancy is also the lowest in Kunhegyes District, similarly to other disadvantaged districts, while the number of preventable early deaths is the highest, both among men and women.

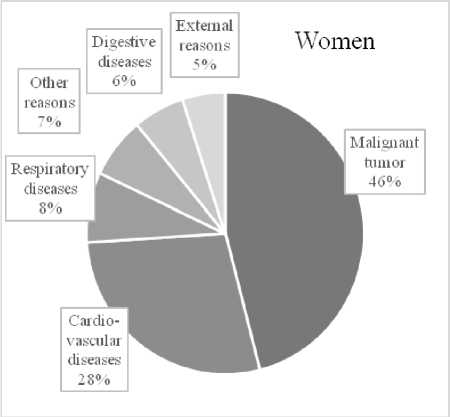

The poorest health indicators are produced by the Kunhegyesi District, closely followed by Jászapáti District. Most frequent causes of death include primarily cardio-vascular diseases, which is one of the most common cause of early preventable deaths. Vascular deficiency is to blame for consequential diseases such as high blood pressure, ischaemic heart diseases, including acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), as well as cerebro-vascular diseases and stroke.

Vascular diseases are a consequence of a number of factors and habits of lifestyles, such as hypertension, diabetes, lipodystrophy, obesity, distress, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle (Fig. 6).

The examination of the clusters of people entitled to various support and benefits is indispensable in order get an insight into the general condition of the population of Kunhegyesi District. In 2018, 451 persons were entitled to social assistance, 221 to in-home support, 600 to social catering. 4,242 persons participated in family support service programmes, 580 in child welfare services. 67 persons were entitled to day-care services for the elderly, absorbing 73.6% of capacities, while 70 were entitled to elderly home accommodation, absorbing 97.2% of capacities [TeIR, 2018].

We can see that subsidies for the elderly are usually followed by a busy life, while the regular child protection allowance is offered to families where per capita income does not exceed the level specified in Act XXXI of 1997 on Child Protection and Adoption Service. The entitlement for regular child protection allowance also entitles for free or discounted social catering for children, including catering during holiday, in-kind assistance or other allowances determined by law. Although numbers are decreasing year on year, 3,163 persons on average were entitled to such

Fig. 6. Early preventable death structure of men and women in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, 2013–2017, % Note. Source . Own edition based on [NEKIR, 2019].

allowance in 2019, which makes up 16% of the total population, with outstanding data in Tiszabura (1,096) and Tiszabő (917 persons).

The family support service provides help with social and mental health issues, and aims to provide help with life skills as well as to help prevent causes that might lead to social and cohabitation crises. This number is rather high in Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, while it is outstandingly high in Kunhegyesi District. Another indicative data is the number of minors looked after by the child welfare services, aiming to provide special personal service for the preservation of physical and mental health of children, their containment within their families, the prevention of their vulnerability, or helping to establish adequate circumstances for the reception of a child after birth or after removal. The most important activities of the child welfare services include counselling, disclosure of information, assistance in official procedures, operation of a reporting system on vulnerability, as well as organisation of holiday programmes.

Conclusions

Current study analysed the Kunhegyesi District of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County from the point of view of demography and examined the changes and trends in composition population, along with employment data and socio-economic performance. The area embraced by River Tisza and Route 44 has been a problem child with serious issues for decades. If it were not for domestic and European Union funding, capital injection and priority development programmes that offer some minimal catching up or at least a slowdown in social degradation, the local population would have no prospects for a brighter future. Local communities are in desperate need for committed professionals who are at their disposal 0– 24. The development pilot programme of the Maltese Charity Service titled Presence has undertaken to achieve results in economic and social development in two settlements of the Kunhegyesi District, Tiszabő and Tiszabura, in active cooperation with local Roma stakeholders, Roma mayors, civil society activists, and minority self-government representatives. Some promising changes have started, such as the number of disadvantaged and at-risk children has decreased, while the number of employed and skilled people has increased. The question is, to what extent these changes are sustainable, and whether there are prospects for self-sustaining local development. I am hoping to find further answers in the future researches.

Список литературы Specificity of socio-economic processes in the Hungarian microregion

- Bukodi E., Paskov M., Nolan B., 2017. Intergenerational Class Mobility in Europe: A New Account and an Old Story. INET Oxford Working Papers, no. 03. Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School. URL: https://academic.oup.com/sf/article-abstract/98/3/941/5477829?redirectedFrom= fulltext.

- Domokos V., 2010. Szegény- és cigánytelepek, városi szegregátumok területi elhelyezkedésének és infrastrukturális állapotának elemzése különbözõ közoktatási, egészségügyi, településfejlesztési adatforrások egybevetésével. Budapest, ECOTREND Bt. URL: https://tamogatoweb.hu/index.php/irasaink1/644-szegregaciotol-a-felzarkozasig-ii-resz.

- Enyedi Gy., Tamási P., 2001. Szegénység Magyarországon. INFO-Társadalomtudomány, no. 54, pp. 3-6. URL: http://real-j.mtak.hu/5374/3/InfoTarsadalomtudomany_054.pdf.

- Gonda V.J., Péli L., Nagyné M.M., 2020. Generációváltás problematikája a tanyasi életformában – fiatalok az élet peremén (a) vagy az, elveszett paradicsomban.

- Studia Mundi – Economica, no. 7 (4), pp. 47-59. DOI: 10.18531/Studia.Mundi.2020.07.01.26-36. URL: http://studia.mundi.gtk.szie.hu/generaciovaltasproblematikaja-tanyasi-eletformaban-fiatalok-azelet-peremen-avagy-az-elveszett.

- Harcsa I., 2018. Vita, hozzászólás: Módszertani tanulságok a társadalmi percepciók mérése kapcsán. Reflexiók Huszár Ákos és Záhonyi Márta, A szubjektív mobilitás változása Magyarországon” címû írásához. Demográfia, no. 61 (1), pp. 91-98. DOI: 10.21543/Dem.61.1.4. URL: http://demografia.hu/kiadvanyokonline/index.php/demografia/article/view/2746

- Havasi É., 2015. A magyarországi létminimum-számítás korszakai nemzetközi összehasonlításban. Statisztikai Szemle, 93/10. URL: https://www.ksh.hu/statszemle_archive/2015/2015_10/2015_10_885.pdf.

- Huszár Á., Záhonyi M., 2018. A szubjektív mobilitás változása Magyarországon. Demográfia, no. 61 (1), pp. 5-27. DOI: 10.21543/Dem.61.1.1. URL: http://www.demografia.hu/kiadvanyokonline/index.php/demografia/article/view/2743.

- Idetartozunk Egyesület (We Belong Here Association), 2019. A kezdetek: 2011. Az identitáspolitika. URL: https://idetartozunk.org/kik-vagyunk.

- Jedynak W., Káposzta J., Kinal J. (Szerk.), 2017. Changes As a Social Process. Rzeszów, University of Rzeszów. URL: http://www.kulturawsieci.pl/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Jedynak-Kaposzta-Kin al-Changes-as-a-social-process.pdf.

- Kirby P., 2006. Vulnerability and Violence: The Impact of Globalisation. Pluto Press, University of Michigan, pp. 130-145.

- Kiss D., Lantos Sz., Marozsán Cs., Németh N., 2013. Jelenlét – A roma integrációt szolgáló fejlesztések megalapozása, szociális munka kirekesztett közösségekben, szegregátumokban. Budapest, Magyar Máltai Szeretetszolgálat. URL: https://jelenlet.maltai.hu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Jelenl%c3%a9t-tanulm%c3%a1ny.pdf.

- Molnár M., Bogárdi T., 2016. Investigating Provincial Hungary: Social Recovery or Recession?

- Jedynak W., Kinal J., eds. Society – Modernity – Change: Selected Issues from Central Europe. Krakow, University of Rzeszów, pp. 93-104.

- Matkovich I., 2011. Népszámlálási kampány romákkal – Fontosabb az eredménynél. Magyar Narancs, no. 42 (10.20). URL: https://magyarnarancs.hu/belpol/nepszamlalasi_kampany_romakkal_-_fontosabb_ az_eredmenynel-77142.

- NEKIR, 2019. Népegészségügyi Elemzési Központ Információs Rendszer. Budapest, Nemzeti Népegészségügyi Központ. URL: http://www.jnszm.hu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/11/45_2019_11_15_kh_mell_egeszseg_2018_tajek.pdf.

- Pénzes J., Tátrai P., Pásztor I., 2018. A roma népesség területi megoszlásának változása Magyarországon az elmúlt évtizedekben. Területi Statisztika, no. 58 (1), pp. 3-26. DOI: 10.15196/TS580101. URL: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/terstat/2018/01/ts580101.pdf.

- Ritter K., 2014. Possibilities of Local Economic Development (LED) in Lagging Rural Areas. Acta Carolus Robertus, no. 4 (1), pp. 101-108. URL: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ags/hukruc/171185.html.

- Ritter K., 2008. A helyi fejlesztés esélyei – agrárfoglalkoztatási válság és területi egyenlõtlenségek Magyarországon. Területi Statisztika, no. 48 (5), pp. 554-572. URL: https://matarka.hu/cikk_list.php?fusz=39925.

- Ritter K., 2017. Analysis of Local Economic Development Capacity in Hungarian Rural Settlements. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae Economics and Business, no. 5, pp. 57-70. DOI: 10.1515/auseb-2017-0004. URL: https://www.sciendo.com/article/10.1515/auseb-2017-0004.

- Ritter K., 2018. Special Features and Problems of Rural Society in Hungary. Studia Mundi – Economica, no. 1, pp. 98-112. DOI: 10.18531/Studia.Mundi.2018.05.01.98-112. URL: http://studia.mundi.gtk.szie.hu/special-features-and-problems-ruralsociety-hungary.

- Sofovic B., Kragulj J., Pop D., 2012. Preventing the Separation of Children from Their Families in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Raynor C., ed. Review of Hope and Homes for Children ACTIVE Family Support Programme in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2003–2010. URL: https://www.hopeandhomes.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/12/BiH-Active-Family-Support-Report_final_LowR.pdf.

- Szur ovec I ., 201 9. Olc sóbb l enne s egíten i a családoknak, mégis inkább elveszik tőlük a gyerekeket. URL: https://index.hu/belfold/2019/05/06/allami_gon dozas_gyerek_kiemeles_tamogatas/.

- TeIR, 2018. URL: https://www.teir.hu/helyzet-ter-kep/kivalasztott-mutatok.html?xteiralk=htk&xids=1057, 1058,1061,1062,1071,1072,1073,1074,1075,1076,1077,1078&xtertip=J&xterkod=164.