Stakeholders’ Attitude on the Use of ICT Tools for Sustainable Propagation of Indigenous Knowledge in Tanzania: A Case of Traditional Medical Knowledge of Medicinal Plants

Автор: Irene Evarist Beebwa, Janeth Marwa, Musa Chacha, Mussa Ally Dida

Журнал: International Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science @ijitcs

Статья в выпуске: 11 Vol. 11, 2019 года.

Бесплатный доступ

Most local communities in Tanzania depend on herbal remedies as the primary source of health care and such knowledge have been stored in the minds of the elderly who pass it on orally to young generations. However, the method is not reliable, as there is a likelihood of gradual loss of such knowledge as the elderly become older and incapacitated. It is at the backdrop of such a scenario that this study investigated the stakeholder’s attitude towards the use of information and communication technology tools in preserving traditional medical knowledge in Tanzania. The study also investigated the existing approaches for managing both traditional medical practitioners, herbaria activities and the difficulties. Both quantitative and qualitative data were employed and the study covered Arusha, Kagera and Dar es Salaam regions where 60 ethnobotanical researchers and 156 traditional medical practitioners were involved. The collected data was analyzed using R and Tableau software. The study indicated that 75% of traditional medical practitioners use story-telling for preserving traditional medical knowledge; 86.53% of practitioners indicated that much of the knowledge has disappeared over generations. More than half (69.87%) of practitioners were aware of the existence of technological devices for accessing the internet and 80.5% of researchers and practitioners believed that Information and Communication Technology tools have benefits in the practice of traditional medicine. From the findings, the study came up with the ICT model solution that can help in documenting, preserving and disseminating traditional medical knowledge and integrate the management of stakeholders in Tanzania.

Traditional medical knowledge, Traditional medicine, Extinction, Indigenous knowledge, ICT, Web-mobile, Digital systems

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/15017085

IDR: 15017085 | DOI: 10.5815/ijitcs.2019.11.04

Текст научной статьи Stakeholders’ Attitude on the Use of ICT Tools for Sustainable Propagation of Indigenous Knowledge in Tanzania: A Case of Traditional Medical Knowledge of Medicinal Plants

Published Online November 2019 in MECS DOI: 10.5815/ijitcs.2019.11.04

Indigenous people are uniquely identified by the practices of their cultural heritage in different aspects of social life that encompass food preparation and preservation, arts, crafts, clothing, housing, agricultural methods, use traditional medicine (TRM). [1,2]. The skills and practices of TRM methods of healing, formulation process, dosage and local beliefs used in maintaining health, are collectively referred to as traditional medical knowledge (TMK).

Since antiquity, TRM has been used by many people to treat and prevent both human and animal diseases [3]. Indeed traditional medical practices have been an important component in the healthcare system in Tanzania [4]. Previous studies reports that the practice of TRM is largely attributed to cultural, accessibility and affordability preferences [5,6] and has gained its preeminence in the provision of primary healthcare for local communities around the world thus reports from World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that 80% of the population in Latin America, Asia and Africa directly or indirectly depend on herbal remedies [7–9]. Furthermore, twenty five to thirty percent (25- 30%) of the current modern drugs are directly or indirectly derived from the traditionally known and used medicines that include Phytomedicine or medicinal plants [10–12]. Moreover, TRM can be exploited for possible commercialization by local communities [13].

Traditionally, TMK has been preserved orally by elderly senior members of the community [1,14]. However, such preservation approach does not guarantee sustainable, successful and perpetual management of such a knowledge. This is because such knowledge can easily be lost completely in case the individual with it gets incapacitated or dies. Indeed, existing literature show that, there has been a gradual extinction of TMK in local communities as a result of death and aging of knowledge holders and lack of interest to learn by the younger generation [15].

The government of Tanzania recognizes the use of TRM and practitioners under the Traditional and Alternative Medicines Act of 2002 and it established the Traditional and Alternative Health Practice Council (TAHPC) with the mandate and responsibility of regulating the use of TRM and traditional medical practitioners (TMPs) [17]. Additionally, the government established the Institute of traditional medicine (ITM) under Muhimbili University College to collaborate with traditional healers for improving TRM and possible innovation of modern drugs [18].

Furthermore, The National Herbarium of Tanzania was also established to work on collecting the flora of Tanzania including medicinal plants species [19]. However, these initiatives have not been implemented with the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tools. For instance the registration of stakeholders such as TMPs and the process of capturing and preserving TMK about medicinal plants in the herbaria are done by the use of papers or spreadsheets where management and handling of such data is still challenging.

Various studies have demonstrated that the use of tools for managing TMK is vital in the process of capturing, preserving and disseminating of indigenous knowledge [20–23]. Additionally, ICT tools can be deployed to manage TMPs and practices of medicinal plants [24].

In this study, qualitative and quantitative methods were used to identify and asses the existing approaches used to preserve TMK, the attitude, perception and readiness of stakeholders toward the use of ICT tools in managing TMK, stakeholders and the herbaria in Tanzania. The study also proposes a solution for managing TMK in relation to its stakeholders.

This paper is organized into eight parts. From section two to six are related works, material and methods, results, discussion and the designed solution. These sections describe how previous studies intended to document TMK with the use of ICT and their drawbacks, how the study was undertaken, visualization of the findings, the interpretation and the modelled solution respectively. The last two sections describe the drawn conclusion and the constraints of the study.

-

II. Related Works

The overgrowth and advancement of technology has led to need and urgency of digitization of various contexts of social life including traditional practices. Digitization is vital in the process of documenting and preserving TMK. It can optimize and reduce the risk of vanishing of such knowledge while improving its accessibility to stakeholders [25].

Global studies have reported that there are initiatives done by some countries towards protecting TMK from either loss or bio-piracy. A study was conducted to develop a tool for managing the biodiversity in Tanzania i.e. biodiversity information management tool (BIMT). However, the tool captures the available flora while excluding TK [28]. The established bodies in Tanzania for managing indigenous knowledge such as ITM, NHT, and TAHPC, rely on the use of papers and electronic text documents to manage TMPs and their knowledge.

In India, traditional knowledge (TK) digital library (TKDL) is used to protect the bio-piracy of TMK which is linked to patent examiner globally [29]. However, TKDL does not provide integration of traditional practitioner management within the system.

The study was conducted by Hidaya et al [2] which showed that TMK is disappearing in Indonesia. To address the issue, a model for mobile application to document TK in Indonesia was developed. Though, the study was based on the situational requirement of TK in Indonesia.

Traditional Chinese Medicine Integrated Database (TCMID) was developed in China to integrate the relationship between phytomedicine and the relevant diseases they treat but TCMID is based on the association between herb and disease rather TMK sources and its preservation [30].

Nakata et al [14] conducted a study in Australia, and the findings indicated that a software tool can simplify the process of capturing and disseminating indigenous knowledge to the communities and the general public. However, the study was specifically on astronomical indigenous knowledge rather than medicinal plants.

Indeed proposed solutions are essential in preserving indigenous knowledge. Nevertheless, more of these proposed solutions are more localized in which are developed depending on the requirement of each particular country or community. [2,31].

-

III. Materials and Methods

-

A. Study area

The study was carried out in Arusha, Kagera and Dar es Salaam regions in Tanzania in the period of February to April 2019. Arusha and Kagera have been well known among the regions where its local communities make the use of TRM in their health care [5,32,33]. Also, the existence of herbaria and institutions affiliated to TRM in Arusha and Dar es Salaam necessitated the inclusion of these regions in the study. For instance, there are two herbaria in Dar es Salaam, one at the Institute of TRM and the other at University of Dar es salaam (UDSM). The national herbarium of Tanzania (NHT) is located in Arusha at the Tropical Pesticide Research Institute (TPRI).

-

B. Data collection Methods

Both qualitative and quantitative approaches were employed to collect data from TMPs, researchers, curators and TAHPC officers to determine and assess the current methods for maintaining TMK and the attitude and perception of ICT in the practice of TRM by the stakeholders were also assessed. In addition, the study was carried out to investigate the existing systems for managing TMPs, herbaria and their drawbacks.

Qualitative data : A face to face interview using interview guide was conducted among 8 participants involving 2 curators from each of ITM, NHT and UDSM herbaria and 2 officers from Traditional and Alternative Health Practice Council (TAHPC).

Quantitative data : A survey was administered to two categories of respondents’ that included traditional medical practitioners (TMPs) and researchers or surveyors in the field of TRM Simple random sampling techniques were used to obtain the number of respondents where 60 of them were researchers or surveyors and 156 were traditional medical practitioners making a total of 216 respondents.

TMPs from Meru and Arusha rural districts and those from Kyerwa and Karagwe of Kagera region were interviewed through structured questionnaires. Researchers who were involved in the study were from ITM, UDSM and TPRI. Google form and open data kit (ODK) were used to capture the data from respondents.

-

C. Data analysis

Data preprocessing was conducted prior to the analysis to make it consistent where Open Refine and Google sheet tools were used. OpenRefine is a powerful and easy tool that processes data cleaning, reshapes and intelligently batch edits both unstructured and messy data [34]. Data analysis for quantitative data were performed using R and Tableau software. Both data visualization and descriptive statistics methods for R were used to visualize the data. R is known for its effectiveness in data handling and it has a collection of intermediate tools used for data analysis [35]. The use of tableau was also influenced by its interactive features and ability to provide dynamic results [36].

-

IV. Results

-

A. Overview of the current approaches for managing TMPs in Tanzania

In Tanzania, the current approaches for managing TMPs is centralized at the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDEC) through TAHPC. The council is currently having 22,102 registered TPMs and the registration is done through the use of forms that are filled manually by the applicants and submitted to the council for official approval. Upon approval, the council fills all the data into MS. Excel for storing such information from applicants. This kind of approach encounters some challenges that include;

Time-consuming : The registration process takes about 120 days or more after the submission of application due to postage and payment procedures leading to delay of the registration process.

Difficult to retrieve information : The use of spreadsheet and manual forms for managing TMPs poses a challenge on efficient and fast data retrieval. Manually sought data lead to inaccuracy of information and makes it harder to offer and track licenses after expiration.

-

B. A Summary of the present approaches for managing herbaria in Tanzania

Collecting and curating botanical species including those with medicinal purposes is among the activities carried out by the herbaria. The study found out that both herbaria at NHT, IMT and UDSM have almost similar methods of collecting and preserving medicinal plant species. Traditionally, after plant species have been collected, they are dried and preserved on the papers. Both NHT and ITM are trying to digitize information on plant species from the papers. The following are the summary of how each herbarium works and the challenges encountered;

NHT : The national herbarium of Tanzania make use of papers, MS excel, botanical research and herbarium management system (BRAHMS) for keeping medicinal species records.

ITM : The herbarium at the Institute of Traditional Medicine uses papers and MS Excel. ITM possesses over 10,000 plant species and less than 50 of them are documented on both papers and MS excel.

UDSM : The herbarium of the University of Dar es salaam is largely using papers. Although in 1996, MS access database was deployed to document collected plant species. However, the database has never been updated with new species since its launch.

The study observed that most of the data in the herbarium is stored mostly on papers and therefore remain inaccessible to many people, Curators also face difficulties in organizing and retrieving specific plant species information when required and some files holding certain information about medicinal plant species unreadable with time.

Furthermore, the study revealed that the NHT system has difficulties with BRAHMS software where most of the requirements are not relevant to the country’s demands. For instance, the system can’t be updated on changes in the location name of a certain plant species and is only accessible to staffs at the hosting institution. BRAHMS was specifically developed for keeping records of botanical species that are scientifically identified and not for indigenous knowledge preservation. Quantitative results.

-

C. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Out of 216 respondents, 156 were traditional medical practitioners (TMPs) and 60 were researchers. Table 1 and 2 shows the socio-demographic details of each respondent category.

From Table 1, the number of female respondents were slightly higher (50.64%) than men. The majorities (61%) of TMPs are holding primary school education while only one practitioner is holding university education and the majority (78 %) are aged between 35 and above 60.

Furthermore, the majority of researchers are male (75%) and 91.67% of all researchers have university education while 8.33% have a vocational college education (Table 2). Most researchers (43.33) were between 18 and 34 years of age.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for TMPs

|

Demographic features |

Respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Gender |

Male Female |

77 79 |

49.36 50.64 |

|

under 18 |

4 |

2.56 |

|

|

18-34 |

30 |

19.23 |

|

|

Age (in |

35-44 |

52 |

33.33 |

|

years) |

45-60 |

40 |

25.64 |

|

61 and above |

30 |

19.23 |

|

|

Non formal education |

34 |

21.79 |

|

|

Primary education |

96 |

61.54 |

|

|

Education |

Secondary education |

19 |

12.18 |

|

Vocational college |

16 |

3.85 |

|

|

University |

1 |

0.64 |

|

Table 2. Demographic characteristics for researchers

|

Demographic features |

Respon dents |

Percentage (%) |

|

|

Male |

45 |

75 |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

15 |

25 |

|

18-34 |

26 |

43.33 |

|

|

35-44 |

18 |

30 |

|

|

45-60 |

14 |

23.33 |

|

|

61+ |

2 |

3.33 |

|

|

University |

55 |

91.67 |

|

|

Education |

Vocational college |

5 |

8.33 |

-

D. Existing preservation methods for TMK in Tanzania .

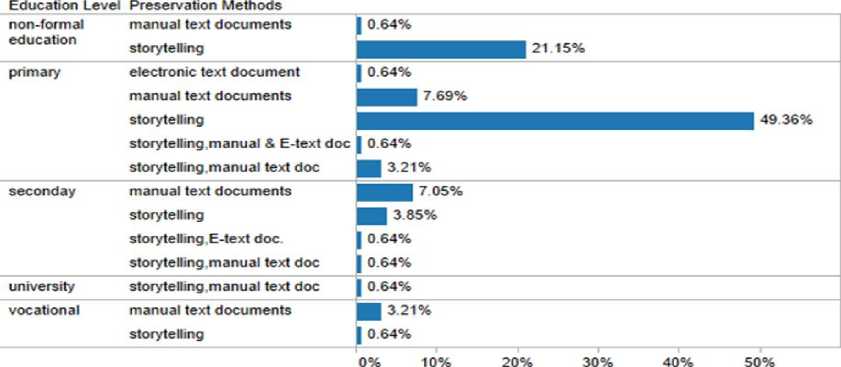

Fig. 1 indicate preservation methods used by TMP and the relevant education levels. The majority Seventy five percent (75%) of all TMPs respondents were using storytelling as the main method for preserving and sharing their knowledge. Other methods such as manual and electronic text documents were found to be used by 15.59% and 0.64% of knowledge keepers respectively. Some TMPs (8.77%) were using both storytelling, manual and electronic text documents simultaneously.

Preservation methods of ТМКш Tanzania

% of Total Number of Respondents

% of Total Number of Respondents for each Preservation Methods broken down by Education Level.

Fig.1. TMK preservation methods used by TMPs with relevant education levels in Tanzania

-

E. Sustainability of the existing methods for TMK preservation in Tanzania

Sustainability of the methods currently used by TMPs in preserving TMK related information are indicated in table 3. All respondents who were practicing storytelling (48.08%) indicated that it was not sustainable in the management of TMK.

Table 3. Sustainability of TMK preservation methods

|

Preservation methods |

Is the preservation methods used sustainable for all generations? |

||||

|

strongly agree |

slightly agree |

neutral |

Strongly disagree |

Slightly disagree |

|

|

e-text doc. |

0.64% |

||||

|

manual text doc. |

1.28% |

4.97% |

3.21% |

0.64% |

4.49% |

|

Storytelling |

7.05% |

16% |

3.85% |

12.18% |

35.90% |

|

Storytelling, e-text doc |

0.64% |

||||

|

Storytelling, manual text doc., e-text doc |

0.64% |

||||

|

Storytelling, manual txt doc. |

0.64% |

0.64% |

1.28% |

0.64% |

1.28% |

-

F. Extinction of TMK in Tanzania

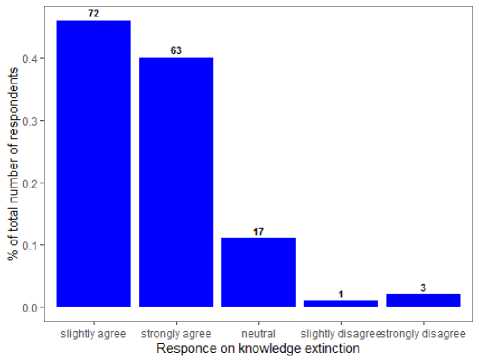

Fig. 2 indicate the opinions collected from the TMPs on the loss of TMK in the local communities in Tanzania. Eighty six percent (86%) of all the TMPs indicated that there has been a gradual extinction of TMK under the passage of generations.

Fig.2. Respondents’ opinions on TMK extinction

-

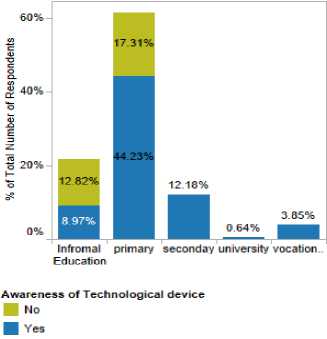

G. Respondents awareness of the existence of technological device and internet usage

A survey was also conducted for TMPs to assess the awareness of technological devices such as mobile phones, computers and tablets. Fig. 3 indicate that, 69.87% of all TMPs were aware of the existence of technological devices for accessing internet. More than half (12.82%) of the total respondents (21.79%) with informal education, were unaware of technological devices while respondents with formal were aware of existing technological devices. These findings indicate that there is a relationship between education level and technological awareness Table 4 indicates internet usage for TMPs and researchers. It was also revealed that all researchers (100%) were able to access internet, while 41.67% of all TMPs access internet either daily, weekly or several times a day or week and 58.33% have never accessed the internet.

Fig.3. TMPs Opinions on the awareness of existence of technological devices

Table 4. Internet accessibility by TMPs and researchers

|

Respondents Category |

Internet accessibility |

Respondents |

Percentage (%) |

|

never |

91 |

58.33 |

|

|

everyday |

28 |

17.95 |

|

|

Practitioners |

several times a week |

14 |

8.97 |

|

several times a day |

6 |

3.85 |

|

|

once per month or less |

12 |

7.69 |

|

|

once per week |

5 |

3.21 |

|

|

everyday |

24 |

40 |

|

|

Researchers |

several times a week |

16 |

26.67 |

|

several times a day |

18 |

30 |

|

|

once per week |

2 |

3.33 |

% of Total Number of Respondents

Respondents category Practitioners

I Researchers

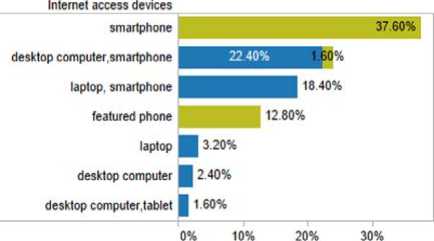

Fig.4. Type of devices used by respondents to access the internet

-

H. Devices used for internet access by TMPs and researchers

Fig 4. Indicates the type of devices used by TMPs and researchers who were able to access the internet from Table 5. The majorities (62.4%) were accessing the internet using either desktop computers, laptop computers, smartphone, tablet or combination of both devices.

-

I. TRM stakeholder’s ICT attitude

From Table.5, respondents in both category i.e. TMPs and researchers gave their opinions on their attitude for using technology as an alternative method in maintaining their knowledge. The majorities (80.55%) of all respondents reported that there are benefits in the use of ICT in managing TMK.

Table 5. Respondent’s ICT attitude in TRM practices

|

Respon-dents |

Percen-tage (%) |

|

|

There are benefits using ICT tools in the practice of traditional medicine |

174 |

80.5 |

|

There is a need for developing a digital system for TMK management in Tanzania |

161 |

74.5 |

|

Automation of TMPs registration and management is crucial |

114 |

73.34 |

|

Integrating herbaria activities under common digital system in can maintain data accessibility and consistency |

52 |

86.6 |

A good number of TMPs and researchers respondents (74.54%) were positive and ready over the use and development of a digital repository in Tanzania to manage TMK.

About 93.34% of ethnobotanical researchers and TMPs indicated the need for incorporating a module for automating TMPs registration while 86.6% of all the researchers were positive on the idea of integrating the herbaria activities within a single digital repository in Tanzania.

Table 6. Respondents’ opinions on the expectation toward the use of digital systems

|

1 Respondents expectation from digital systems |

Respondent s (Researcher s and TMPs) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Optimize TMK extinction |

178 |

82.41 |

|

Improve TMK dissemination |

149 |

68.98 |

|

Improve TMPs Registration |

171 |

79.16 |

|

Improve TMK preservation |

167 |

77.31 |

J. TMK stakeholders’ expectation from the practice of digital systems

Out of the 216 TMK stakeholders who responded, 82.41% believe that the extinction of TMK will be optimized if digital systems will be implemented and used (Table 6). More than half of all respondents (68.98%)

expect improvement on dissemination and accessibility of TMK while 77.31% anticipate enhancement of the process of documentation and preservation. Moreover, 79.16% of respondents believed that there will be an improvement in TMPs registration and management.

-

V. Discussion

This study revealed that TMPs in Tanzania rely on the use of word of mouth (storytelling) as the major method of preserving TMK. It was also observed that there is an association between educational level and the methods used to preserve TMK. Respondents with primary and non-formal education seem to be using storytelling as the main method for preserving and transferring their knowledge while those with secondary education level and above, use storytelling together with either manual or electronic text documents. Previous studies had also indicated storytelling as the main method of preserving TMK by indigenous people [37,38].

The study also found out that, storytelling which was the main means of preserving indigenous knowledge, was not sustainable in maintaining cultural heritage. This is in line with previous studies that had indicated that storytelling doesn’t guarantee successful documentation of TMK [1,39,40].The greater number of TMPs (86.53%) indicated that they are experiencing gradual loss of TMK over generations. Some knowledge about medicinal plants has been totally lost due to ageing and death of the generation that owned the knowledge. Studies have also reported complete loss of TMK caused by aging and deaths of those who owned the knowledge [39,41].

The study found out that there is massive increase in the use of technological devices i.e. smartphones, computers and the internet in Tanzania [42]. According to Tanzania Communication Regulatory Authority (TCRA) report of 2017, 42% of the population of Tanzania were able to access internet [43,44] which correlates to the findings in Table 3 of this study. All researcher respondents (100%) were able to access internet. Greater number of TMPs are also aware of the existence of technological devices such as mobile phones, computers and tablets. These findings imply that it will be possible to implement and access web-mobile application for managing TMK among stakeholders in Tanzania.

Indeed, traditional medical practitioners are helping Tanzanian societies, however, according to the government policy, their services are to be regulated to ensure health safety of the people. TAHPC rely on the use of papers and spreadsheets in the whole process of TMPs authorization. Apparently, the existing system is facing challenges when granting official license and approval. Herbaria which is working on preserving botanical plant species e.g. including those with medicinal purpose, for further reference and study. The process is manual, making the generated information difficult to access by the intended people.

It was found that development of a digital repository for TMK in Tanzania is desirable. A number of stakeholders of TRM i.e. ethnobotanical researchers and TMPs, indicated their need and readiness to use digital systems in implementing traditional medical practices in Tanzania such as automation of TMP registration and integration herbaria activities. Additionally, respondents believed that development and deployment of digital systems will be beneficial for maintaining their cultural practices. Previous studies also argued that ICT can play a potential role in the process of capturing documenting, storing and retrieving of TMK [15].

More respondents had a number of expectations towards the use of digital systems such as the improvement of TMPs registration done by TAHPC, TMK accessibility, and minimization of TMK extinction. Previous study on digitization of TMK reported that ICT has advantage and it can be adopted to protect countries’ cultural heritage and TMK can be best preserved through digitization [23,45,46].

-

VI. The Designed Solution

-

A. A Conceptual framework

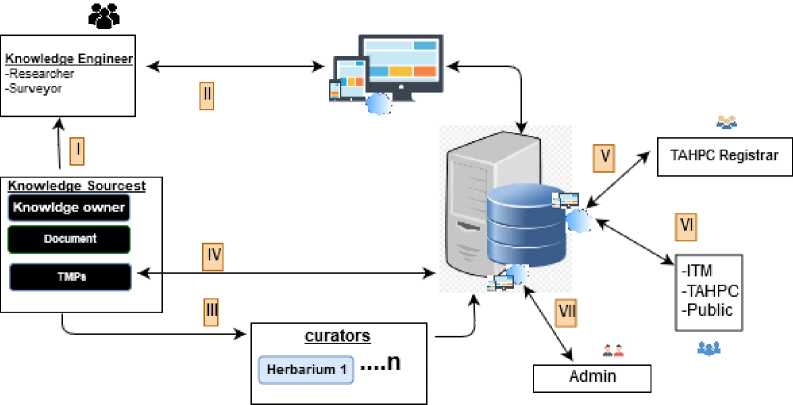

Based on the findings, an ICT model for the solution of TMK management, stakeholders and herbaria activities in Tanzania was developed as shown in Fig. 5. The model is an architectural framework which demonstrates the process of TMK documentation, management of TMPs and integration of herbaria activities under a single database server described in seven parts.

Fig.5. A Conceptual framework for TMK and its stakeholder’s management in Tanzania

Part I : is the interaction between knowledge sources and the knowledge engineers. Knowledge engineers capture TMK data from knowledge sources.

Part II : is the interaction between TMK engineers with the database server. Knowledge engineer submit the collected data from knowledge sources to the database server through the application server.

Part III: is the interaction between curators, knowledge sources and the database server. Curator from the herbarium in Tanzania, receives data about TMK from knowledge sources and submit it to the database server. In addition, curators approve all uploaded data after scientific identification to be available to the public.

Part IV : is the interaction between traditional medical practitioners with the system. TMPs request and apply for registration through the application serve, view registration status and add TMK data

Part V : is the interaction between the TAHPC registrars and the system. The registrar interact with the systems to register and approve TMPs.

Part VI : is the interaction between TMK stakeholders and the system, where they will be able to view TMK available in the public domain and share feedback to the system.

Part VII: is the interaction between the systems administrator with the database server through the application server. The administrator control and manage all activities on web-mobile application and the database server

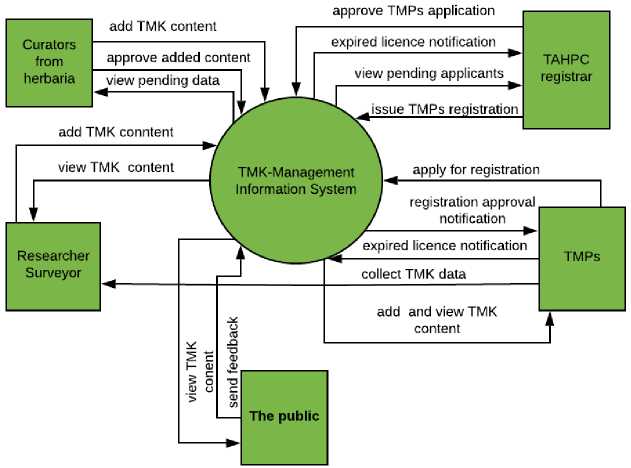

Fig.6. A Context Diagram for a Proposed Solution for TMK Management and its Stakeholders in Tanzania

-

B. Data flow for the proposed and designed solution

In engineering, a data flow diagram (Level 0) is a tool that illustrates the flow of data for the system through the interaction with external entities [47]. It is sometimes referred to as a context diagram and well understandable by both technical and nontechnical stakeholders. Fig.6 below depicts the interaction between the TMK management information system (TMK-MIS) and the external entities. TMK-MIS presents an overview of how information flow between TMK-MIS and its external entities i.e. TMPs, researchers, curators, TAHPC registrar, the public and other stakeholders.

-

VII. Conclusion

Herein, we show the current approaches used by TMPs to manage TMK, participant’s opinions on the awareness of technological devices for accessing the internet, internet accessibility and attitude on ICT and TRM practices in Tanzania. We also examined the usefulness of digital systems in documenting TMK to make it available and more accessible for all generations. In fact, suitable innovation for healthcare system can be derived from TMK if preserved.

The findings also show that there is a challenge in -vanishing of TMK of indigenous people and the whole community. TMPs and researchers who participated in the study indicated that valuable herb remedies knowledge that could be used over generations for primary health care has been lost due to inability of current approaches in perpetually holding such knowledge.

Considering the eagerness and positive attitude of stakeholders, internet accessibility and the relevant technological devices used, a web-mobile application can be the way forward for TMK management and its stakeholders in Tanzania.

-

VIII. Limitations of the Study

Only traditional medical practitioners who were practicing medicinal plants and ethnobotanical researchers were interviewed and only TMK that are in the public domain were used as the case study.

Acknowledgement

I would like to render my sincere gratitude to Dr. David Nyakundi, Dr. Elaine O. Nsoesie and Mr. Chrian Mkombozi Marciale for their tireless supports and advice to accomplish this work. I also wish to thank ITM, NHT, TPRI and the herbarium of the University of Dar es Salaam for their cooperation during data collection. This study was fully funded by the African development bank (AfDB).

Список литературы Stakeholders’ Attitude on the Use of ICT Tools for Sustainable Propagation of Indigenous Knowledge in Tanzania: A Case of Traditional Medical Knowledge of Medicinal Plants

- Anyaoku EN, Nwafor-Orizu OE, Eneh EA. Collection and Preservation of Traditional Medical Knowledge: Roles for Medical Libraries in Nigeria. J Libr Inf Sci. 2015;3(1):33–43.

- Hidayat E, Sensuse DI, Sucahyo YG, Noprisson H. Development of Mobile Application for Documenting Traditional Knowledge in Indonesia. 2016;

- Yuan H, Ma Q, Ye L, Piao G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules. 2016;21(5).

- MoHCDEC. THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA The National Health Policy 2017 Sixth Draft Version For External Consultations with Ministries, Departments and Agencies. 2017;(October). Available from: http://www.tzdpg.or.tz/fileadmin/documents/dpg_internal/dpg_working_groups _clusters/cluster_2/health/JAHSR_2017/8.The_Nat_Health_Policy_2017_6th__24_October__2017.pdf

- Stanifer JW, Patel UD, Karia F, Thielman N, Maro V, Shimbi D, et al. The determinants of traditional medicine use in northern Tanzania: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):1–17.

- Wassie SM, Aragie LL, Taye BW, Mekonnen LB. Knowledge, Attitude, and Utilization of Traditional Medicine among the Communities of Merawi Town, Northwest Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med. 2015;2015:1–7.

- Haouari E, Makaou SE, Jnah M, Haddaouy A. A survey of medicinal plants used by herbalists in Taza (Northern Morocco) to manage various ailments. J Mater Environ Sci J Mater Environ Sci. 2018;9(6):1875–88.

- Mahomoodally MF. Traditional medicines in Africa: An appraisal of ten potent African medicinal plants. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013(June).

- WIPO. Intellectual Property and Traditional medical knowledge. 2016;(134):1–4.

- Kayombo E, Mahunnah R, Uiso F. Prospects and Challenges of Medicinal Plants Conservation and Traditional Medicine in Tanzania Edmund. 2013;1(3):1–8.

- Shakya AK. Medicinal plants : Future source of new drugs. Int J Herb Med. 2016;4(4):59–64.

- WHOAFRO. Health Monitor. 2012;2016.

- Abbott R. Documenting Traditional Medical Knowledge. World Intellect Prop Organ [Internet]. 2014;(March):48. Available from: http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/tk/en/resources/pdf/medical_tk.pdf

- Nakata M, Hamacher D, Warren J, Byrne A, Pagnucco M, Harley R, et al. Using Modern Technologies to Capture and Share Indigenous Astronomical Knowledge. Aust Acad Res Libr. 2014;45(2):101–10.

- Du Y, Guo L, Xue D. TKDL: A new tool in protecting and managing traditional knowledge of China. Proc - 2013 6th Int Conf Intell Networks Intell Syst ICINIS 2013. 2013;204–7.

- Vissers J, Bosch F Van Den, Bogaerts A, Cocquyt C, Degreef J, Diagre D, et al. Scientific user requirements for a herbarium data portal. 2017;57:37–57.

- URT. the Traditional and Alternatne Medicines Act, 2002. 2002;

- MUHAS. Institute of Traditional Medicine [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.muhas.ac.tz/index.php/academics/muhas-institutes/110-itm

- JSTOR. National Herbarium of Tanzania [Internet]. 2018. Available from: Hearing

- Adebayo JO. Documentation and Dissemination of Indigenous Knowledge By Library Personnel in Selected Research Institutes in Nigeria. 2017;

- Cueva M, Kuhnley R, Revels LJ, Cueva K, Dignan M, Lanier AP. Bridging storytelling traditions with digital technology. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(SUPPL.1).

- Rao NS. ICT Applications in Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. 2016;3(1):27–9.

- Sharma AK. Indigenous Knowledge Communication in the 21 St Century. 2014;128–35.

- Kasilo OM, Trapsida J-M. Regulation of Traditional Medicine in the WHO African Region. African Heal Monit. 2013;(14):25–31.

- Koumpouros Y, Birbas K, Kapodestrian N. 7 (2013),i. 2013;7.

- Hunter J. The role of information technologies in indigenous knowledge management. Aust Acad Res Libr. 2005;36(2):109–24.

- Ghosh P, Palbag S. TKDL : AN ANSWER TO BIOPIRACY IN INDIA. 2017;5(11).

- AIMS. Tanzania Biodiversity Information Management Tool (BIMT): access data delineating areas of high biodiversity conservation priority in Tanzania. 2016; Available from: http://aims.fao.org/activity/blog/tanzania-biodiversity-information-management-tool-bimt-access-data-delineating-areas

- Nadkarni A, Rajam S. Capitalising the Benefits of Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) in Favour of Indigenous Communities. NUJS L Rev. 2016;9:183–216.

- Xue R, Fang Z, Zhang M, Yi Z, Wen C, Shi T. TCMID : traditional Chinese medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. 2013;41(November 2012):1089–95.

- Mangare CF, Li J. A Survey on Indigenous Knowledge Systems Databases for African Traditional Medicines. 2018;(May):9–15.

- Moshi MJ, Otieno DF, Mbabazi PK, Weisheit A. Ethnomedicine of the Kagera Region, north western Tanzania. Part 2: The medicinal plants used in Katoro Ward, Bukoba District. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6(1):19.

- York N, Garden B. Plants Used in Traditional Medicine by Hayas of the Kagera Region , Tanzania Author ( s ): S . C . Chhabra and R . L . A . Mahunnah Published by : Springer on behalf of New York Botanical Garden Press Stable URL : http://www.jstor.org/stable/4255597 . PLA. 2014;48(2):121–9.

- Zhuang H, Vedvyas I, Dole R. Tutorial: OpenRefine. 2011;

- Venables WN, Smith DM. An Introduction to R. 2019;0.

- Sood A, Sinha N, Dewjee S, Zhao W. Tableau Tutorial User Documentation. 2018; Available from: https://casci.umd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tableau-Tutorial.pdf

- Slade J, Yoong P. the Types of Indigenous Knowledge To Be Retained for Young New Zealand Based Samoans : a Samoan Grandparents ’ Perspective. 2014;

- Chiwanza K, Musingafi MCC, Mupa P. Challenges in Preserving Indigenous Knowledge Systems : Learning From Past Experiences. 2013;3(2):19–26.

- Owiny SA, Mehta K, Maretzki AN. The use of social media technologies to create, preserve, and disseminate indigenous knowledge and skills to communities in East Africa. Int J Commun. 2014;8(1):234–47.

- Devi S, Thapa N. Preservation of the Traditional Knowledge of Tribal Population in India. 2015 4th Int Symp Emerg Trends Technol Libr Inf Serv. 2015;99–103.

- Dlamini PN. Use of Information and Communication Technologies Tools to Capture, Store, and Disseminate Indigenous Knowledge. 2017;(1995):225–47. Available from: http://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-5225-0833-5.ch010

- Mwammenywa IA, Kaijage SF. Towards Enhancing Access of HIV/AIDS Healthcare Information in Tanzania: Is a Mobile Application Platform a Way Forward? Int J Inf Technol Comput Sci. 2018;10(7):31–8.

- Obulutsa G. Tanzania internet users hit 23 million; 82 percent go online via phones: regulator [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-tanzania-telecoms/tanzania-internet-users-hit-23-million-82-percent-go-online-via-phones-regulator-idUSKCN1G715F

- TCRA. Tanzania Internet Users [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.tanzaniainvest.com/telecoms/tanzania-mobile-phone-subscribers-records-steady-growth-of-25-in-2015

- Plockey FD. The Role of Ghana Public Libraries in the Digitization of Indigenous Knowledge : Issues and Prospects. J Pan African Stud [Internet]. 2014;6(10):20–36. Available from: http://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol6no10/6.10-4-Plockey.pdf

- Sraku-Lartey M, Acquah SB, Samar SB, Djagbletey GD. Digitization of indigenous knowledge on forest foods and medicines. IFLA J. 2017;43(2):187–97.

- Fallis A. Building management tools/approaches for building tools/system modeling tools. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53(9):1689–99.