Study on the global factories in the sociological literature

Автор: Sezenov Ivan I., Borisovich Andrey B.

Журнал: Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems @imcra

Статья в выпуске: 7 vol.8, 2025 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The topic of economic globalization has fascinated social scientists for several decades. In fields as diverse as anthro-pology and economics, theorists have debated whether trade liberalization, transnational capital flows and transnational production networks are good for development and civilization. Over the years, polemics have emerged on both sides of the platform. Neo-liberal economists assert that economic integration is a preeminent source of development and stabilization. Conversely, leftist intellectuals decry global integration as a process that halts development and lets wealthy nations and powerful corporations extract and appropriate resources and labor from poorer countries. While debates on global integration frequently involve discussion of nations, cultures, factories and households, it is possible to reframe these questions so that they focus more on individuals. Global integration is not merely participation in the world economic system— the act of sewing or assembling goods—instead, it can be thought of as the state of being globalized, both in terms of work-force participation and cognitive sense making, the process by which workers in glob-ally- integrated workspaces make sense of their roles within them. Furthermore, integration can be evaluated in terms of the quality of global economic information workers posses, the way they acquire it, and how this information is used. By considering globalization in such a light, we establish not just the mere ―fact‖ of integration, but also the ―de-gree‖ of integration that exists in a locality and the variety of responses to it.

Sociologic literature, global factories, sociological study

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/16010848

IDR: 16010848 | DOI: 10.56334/sei/8.7.24

Текст научной статьи Study on the global factories in the sociological literature

Sezenov Ivan I., Borisovich Andrey B. (2025). Study on the global factories in the sociological literature. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context ofModern Problems, 8(7), 204-223; doi:10.56352/sei/8.7.24.

4 the CC BY license .

Thus, taking global integration to be rooted both in experience and cognition, this paper examines how garment workers in the globally- integrated Kenyan apparel industry make sense of their lives and their work. I have selected Kenya’s 38,000 garment workers as the focus of my study because of the complex transnational network they are enmeshed in via their work. Since the passage of the U.S African Growth and Opportunity Act in 2000 (AGOA), Kenya has metamorphosed from a fledgling producer of domestic apparels to the third largest garment exporter in Sub Saharan Africa. $266 million dollars of Kenyan apparel were shipped to the United States in 2005, constituting 59% of Kenya’s exports for the year (EPZA 2005). By outperforming other export industries, apparel manufacture in Kenya has become a preeminent source of regional and global economic integration.

Integration into the global economy has also made the Kenyan apparel industry extremely volatile.

Since the World Trade Organization’s apparel quota regime expired on January 1st, 2005, American buyers who source in Kenya have begun patronizing low cost producers in South and East Asia. Thus far, the consolidation of garment manufacture to Asia has led to the closing of seven garment factories in Kenya. However, the reconfiguration of the garment industry has the potential to cause even more damage over time. The expiration of MFA quota provisions is often compared to the tsunami of 2004, because it will potentially deprive more than half a million workers in the “global periphery” of their basic livelihoods (Barboza 2005).

Considering the complex transnational linkages that garment manufacture has created in Kenya, as well as the global economic processes that now appear to be threatening its existence, this project investigates what economic integration means from the vantage point of workers. Specifically, I seek to understand how Kenyan apparel workers understand and interpret their position in global production systems, what factors influence their processes of sensemaking, and how this knowledge gets accrued, transferred and assimilated by workers inside and outside the factory setting. Here, sensemaking refers to the process of “constructing, filtering, framing and creating fac-ticity”—or, developing new understandings of self, environment and society based on experience and learning (Turner 1987, Weick 1995: 14).

Discussion of global factories in the sociological literature

By exploring the experiences of Kenyan apparel workers, my inquiry contributes to an important body of research concerning global factory work. Since the rise of export processing zones in the late 1970’s, many scholars have written on globalized factories as they relate to development, female wage work, workers rights and labor organizing. Through discussion of workplace harassment, the feminization of poverty and changing modes of household reproduction, research on global factories has enlivened debates on globalization and expanded notions of development to include both economic and social indices (Zohir and Paul-Majumder 1994, Dani 1997, Sharmin Absar 2001. Ward et al. 2004, Ross 1997, Rothstein and Blim 1992, Collins 2003).Despite its thorough treatment of women, labor and globalization, the literature on global factories does not explore the processes of sensemaking which take place among overseas workers. Most scholarship on global factories discusses the macro- processes of manufacture without exploring the micro-processes inherent within: particularly, the ways that workers produce their self- concepts and make sense of their embeddedness in volatile, exploitative and globally-integrated production processes. This is true even of ethnographic work on the garment and apparel industry. Generally, the majority of anthropological studies on garment work limit their discussion of these subjects to the topics of social reproduction, household production and labor insurgency (Fernandez Kelly 1983, Igelsias Pierto 1985, Carvey 1998).

The best treatment of worker subjectivities and sensemaking in globalized workplaces can be found in the anthropological writings of Chung Yuan Kay (1994), Margaret Tally (2003) and Pun Ngai (2005), which focus on the topic of export manufacture in East Asia. Chung Yuan Kay’s “Conflict and Compliance: The Workplace Politics of a DiskDrive Factory in Singapore” expands the frame of traditional factory research by examining the discourses on work that exist among Singaporean factory workers. Here, the author’s analysis centers on worker’s “personal stores of knowledge” and their everyday acts of resistance. She concludes that women workers resist and contest managerial control through “verbal subterfuge,” shop floor collusion, and other [subtle] acts of insubordination (Kay 1994: 217). The sum of these parts is factory consciousness, which Kay characterizes as redrawing of “the limits of control at the point of production,” and denying management some “power to be” (Kay 1994: 223).

Pun Ngai’s (2005) Made In China also theorizes about the female “worker-subject.” Tracking female migrant workers on the shop floor, in factory dormitories, and in the center city as they shop for goods, Ngai concludes that women’s experiences are multi-sited and multilayered, consisting of both “domination and resistance, dream and desire and hope and anxiety” (Ngai 2005: 163). Her analysis points out that workers experience their employment in globally integrated companies in subjective and oftentimes contradictory terms. Within the lives of the workers that

Ngai follows, we see an interwoven tapestry of frustration and fulfillment that is constantly battled with and negotiated.

Last within this group, Margaret Tally’s “The Illness of Global Capitalism,” explores the way in which frustration is embodied among female customer service workers. Premising her study on the fact that “workers bodies have not been actively theorized in studies of labor,” Tally observes that female workers’ bodies are commodities in production processes as well as vessels for instrumental and physical pain (Tally 2003: 4). Consequently, although Tally’s work does not perform discourses analysis per se, it examines a subject that my research is deeply invested in: namely, the way that work influences women’s senses of self, their “persons” and their daily lives.

Yet, while these authors make significant contributions to our understanding of worker subjectivities, they overlook a topic that is central to this study—namely, the topic of how workers acquire global economic information and how they incorporate it into their lives as workers. Within the field of research pertaining to globally-integrated industries, the only literature that shares my interest in this topic is research on transnational advocacy networks, or TANs (Featherstone 2002, Feldman 1997, Streeten 1997, Keck and Sikkink 1998, 2001). In “Transnational Advocacy Networks in International and Regional Politics,” anthropologists Keck and Sikkink (1998) develop a political process model that describes the way that knowledge is created and transferred between actors in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Here, the authors conclude that information is a resource that players in the South give activists in the North so that they can raise awareness about their struggles and further their advocacy initiatives (Keck and Sikkink 1998).

Though insightful, the limitation of this TAN analysis is that it revolves around a circumscribed set of partic-ipants—namely, globally integrated workers and foreign activists. Although there is a history of transnational activism in Kenyan EPZs, I cannot limit my analysis to this class of interactions alone, nor can I presume that information is important to workers solely because of its potential as an advocacy tool (Keck and Sikkink 1998). Given Keck and Sikkink’s limiting definitions, my research expands the conceptual frame of TAN research by examining the role of global economic information in workers’ own processes of sensemaking, and by looking at all of the points where social networks, knowledge, consciousness and experience intersect— not just the points which involve Northern activists.

Beyond social movement network theory, this paper also benefits from research in organizational and social psychology. In Gender Symbolism and Organizational Cultures, Gherardi (1995) argues that workers’ identities and discourses on employment are mediated by their position in gender binaries and social hierarchies. Similarly, Stanley Harris (1994) asserts that workers make sense of their jobs through “schemata,” or subjective knowledge systems based on past experience (Harris 1994: 308). Harris identifies three types of schemata that are relevant to workers’ self conceptions: self-in-organization schema,” “person-in- organization schema, and “organizational schema (Harris 1994: 318). These schemata are both reflexive and subjective: workers’ impressions are shaped by the way they deconstruct the organizational world around them. Since my investigation centers on one case study, I will not make broad claims regarding how workers in the Southern Hemisphere perceive global production and economic globalization. Nevertheless, my project will make noteworthy contributions to sociological theory and research. I hope to illuminate topics that have not been fully explored in the literature. In addition, my research will enrich existing studies on the Sub Saharan apparel industry by introducing qualitative analysis and bringing research on Kenyan garment industry up to date with the post-MFA period (Gibbon 2003, 2004, 2005; Gibbs 2005, McCormick 2001, McCormick, Kinyanjui and Ongile 1997).

Finally, I anticipate that my project will enhance global factory research by broadening its focus to include, rather than exclude, analysis of men’s experiences. Contrary to traditional suppositions, men are not absent from garment firms, nor are they managers or solely supervisors; instead, they range in scope from machine operators and pressmen to washers and packers, who work in departments alongside women. In making sense of workers’ embeddedness in global production networks, it is important to examine workers of both genders and to consider their lives on the shop floor as well as outside the firm. Although this approach breaks from the precedent of the literature,1 it allows me to analyze the ways that gender and social location affect workers’ experience of global integration.

Background on the Kenyan export apparel industry

The rise of garment manufacture in Kenya can be traced to the passage of the U.S. Trade and Development Act of 2000, better known as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Before the advent of AGOA, only two dozen EPZ firms were operational in Kenya and apparel was manufactured solely for domestic consumption. Today, however, Kenya has 74 EPZ firms – with more

-

1 Although its findings do not engage my own research,

Salzinger’s (2004) Genders in Production is a refreshing exception to this trend.

Thanks to AGOA’s provisions concerning duty-free and quota-free apparel export privileges for beneficiary countries, apparel manufacture has become a critical industry in Kenya and one of the nation’s largest employers. EPZ garment firms employ upwards of 1,200 workers each and are some of the largest formal employers of women in the country. Of the 37,723 Kenyans that work in EPZs in Nairobi, Mombasa and Athi River, an estimated 80 percent are female garment workers (EPZA 2005). Export processing zones are also a preeminent source of foreign investment in Kenya, albeit portfolio investment. The primary buyers of Kenyan apparel are American retailers like Wal-Mart, Target, Sears and Match point, among which Wal-Mart is the largest customer. In addition, a wide range of brand marketers source their garments from Kenya. These include Jor-dache, U.S. Polo, Joe Boxer and Dickies (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003b).

Within the literature on global production networks, Kenya’s apparel industry can be classified as a buyer-driven commodity chain (Gereffi 1994). This term denotes information regarding both industry structure and industry control. In regards to structure, the Kenyan garment industry is a buyer driven commodity chain because it is “highly competitive and globally decentralized factory system with low entry barriers” (Gereffi 1994, Gereffi 2001: 3). Meanwhile, in terms of industry control, the Kenyan garment industry is buyer-driven because retailers, fashion designers and branded manufacturers are the lead agents of production.

For theorists like Gereffi (1994), economic development and industrial upgrading occur on buyer-driven commodity chains when suppliers wrest control from their buyers and assume larger and more diversified roles in produc-tion—which is to say, greater levels of horizontal integration. This paradigm aptly describes the range of conflict that actors in the Kenyan apparel industry have faced since the growth of the industry in 2000. For officials at the Kenyan Export Processing Zone Authority, conflict has revolved around the struggle to realize national development goals vis a vis an industry known for portfolio investment, labor-exploitation, and destabilizing competition.

Meanwhile, among workers, conflict has consisted of the struggle for sustenance vis a vis employment that lacks regularity and stability, both in terms of work hours and future prospects. Finally, among factory owners, the struggle has been to adapt to global economic pressures and buyer demands whilst maintaining a labor regime and a regulatory environment that is designed to ensure profit. Thus, the struggle for development (and alternately profit) vis a vis Kenya’s labor-intensive garment industry has been a struggle for value chain governance amongst various actors2 Nonetheless, the struggle for export-led development in Kenya has also been a struggle for sustainability at the industry level. As an AGOA beneficiary, Kenya faces competition from African countries that also benefit from U.S. trade concessions: namely Lesotho, Swaziland, Madagascar, Botswana, Namibia, Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Mauritius (AGOA info 2006).3 As a recent entrant into export apparel industry, however, Kenya also competes with better- established garment manufacturers in East Asia, South Asia and Latin America. Competition with these countries has been particularly stiff in wake of the WTO’s recent deregulation of the apparel market. When compared to Kenya, buyers to the Chinese market benefit from the comparative value of Chinese labor, the convenience of locally- produced threads and textiles, and the availability of full package manufacturers, or garment firms that source their own raw materials and assist their buyers on issues related to fashion design (Bair and Gereffi 2003).

Unlike its competitors in China, full package garment manufacture and raw material production do not occur in Kenya. Instead, manufacturers in the Kenyan industry import their thread, yarn and textiles from East Asia and sew them locally. Not only does this arrangement prevent capital from accruing locally, it jeopardizes manufacturers because it relies on Kenya’s continued recognition as a Less Developed Country under AGOA. Under the LDC Beneficiary Clause, Kenya is exempt from stipulations that require AGOA garments to be made from African or American textile. When the LDC Beneficiary Program expires in September 2007, Kenyan manufacturers will be forced to source costly local fabrics, a shift which analysts predict will be the death knell of the industry (Kathuri 2005).

The precariousness of investment in the Kenyan garment industry is a constant source of anxiety for policymakers, and as a result, policies on apparel work are constantly being reformulated by the government. In 2004 and 2005 the Value Added Tax was briefly levied in 2004 in order to generate government revenue, but after a flurry of threats, the VAT on textile imports was dropped (Akumu 2004). Then, in the aftermath of the failed tax levy, parliamentarians fielded proposals to expand the EPZ sector at large and extend the ten year tax holidays for EPZ investors by another five years -- a move that would absolve companies of their duty to pay corporate tax and VAT for the entire duration of AGOA (Anyanzwa 2004). Officials at the Kenyan Export Processing Zone Authority

-

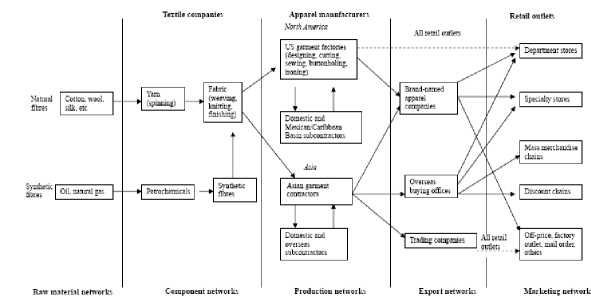

2 See Appendix A for a graphical depiction of a global apparel chain

(EPZA), Kenyan Ministry of Planning and Development and Kenyan Association of Manufacturers have also begun planning an initiative that would create an indigenous cotton industry (Ndurya 2006). This project responds to global commodity chain theory concerning the importance of horizontal integration to development (Gereffi 1994).

Outside the sphere of macroeconomic policy, however, the Kenyan government takes a largely laissez-faire approach to managing the export sector. Kenya’s export apparel industry is primarily foreign- owned and heavily privatized. Of the 41 Export Processing Zones that exist in Kenya, 14% are Kenyan owned, 28% are jointly owned, and 58% are owned exclusively by foreigners (U.S. Department of State 2006). Similarly, only one EPZ in Ken-ya—the Athi River EPZ in AthiRiver, Kenya—is publicly managed (U.S. Department of State 2006).

Private investment, however, is just one facet of Kenya’s institutionalized laissez faire philosophy. The government agencies that oversee export manufacture in Kenya also take a laissez faire approach to labor regulation. The best evidence of this disposition can be found in the government’s handling of a 2003 EPZ strike that saw garment country-wide workers walk off their jobs and protest conditions (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003a.). Although stakeholders organized forums between workers and employers within the first weeks of the strike, negotiations broke down following pressure from factory owners (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003a). Rather than address worker’s grievances, the Minister of Labor opted to declare their work stoppage illegal and give factory managers permission to dismiss them all (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003b).

The short term consequences of this authorization were disastrous. On February 3, 2003, more than 9,200 EPZ workers were dismissed from their jobs abruptly and without receipt of their terminal benefits (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003b). Retrenched workers were forced to reapply for their jobs while labor organizers were blacklisted from EPZ work entirely. The government also implemented a detrimental salary plan that changed workers’ status from casual to permanent but reduced real wages considerably (Wasonga 2006). Consequently, the only real achievement of the 2003 strike was winning union recognition, and even the reach of this victory was limited due to concerns among investors that unions would increase their costs prohibitively.5 In the end, the only EPZ that came to have Unions was the publicly managed export processing zone in Athi River.

The failure of the labor movement was not due to a lack of awareness on the part of the government, however. The problems of low wage, forced and unpaid overtime, sexual harassment, verbal harassment, unpaid maternity leave and occupational hazards that are endemic to the Kenyan garment industry are well known by Ministers and government officials. While conducting interviews at the EPZA Headquarters in Athi River, an official told me: “If only wages could be higher... things are really tough for workers.” Thus, the government’s suppression of the EPZ workers movement demonstrates the extent to which “investors’ rights” are valued over workers’ rights.

Despite the government’s stony disposition towards workers, export processing zones have been a target of advocacy for several non- governmental organizations (NGOs) in Kenya. Throughout the strike of 2003, a nongovernmental organization called the Kenya Human Rights Commission lobbied alongside workers for improved working conditions. These efforts garnered the solidarity of international labor organizations like the Clean Clothes Campaign. The CCC issued an urgent appeal on its website urging its supporters to write letters to Wal-Mart, Target, and the Kenyan Ministry of Labour (Kenya Human Rights Commission 2003a). Representatives from the Clean Clothes Campaign also traveled to Kenya in April 2003 to assess EPZs conditions for themselves.

In the years following the unsuccessful strike in the EPZs, the Kenya Human Rights Commission has involved EPZ workers in rallies concerning workers rights in the sectors of garments, agriculture, and horticulture, invited workers to one-day seminars on workers rights, and published literature on EPZ conditions using grants from the Clean Clothes Campaign and Oxfam (Ouma 2005). In addition, the Tailors and Textiles Workers Union continues to try and register EPZ workers outside of Athi River, albeit unsuccessfully and rather half heartedly (Wasonga 2006).

RESEARCH METHODS AND DESCRIPTION OF DATA

The findings of this project are based on three months of qualitative fieldwork in Kenya. Between June and August 2005, I completed 50 formal, in-depth interviews with garment workers using the snowball sampling method.6 My respondent pool was diverse in terms of place of work, job title, current employment status, length of time on the job, prior work history, educational background and marital status. My respondent pool was also unique due to its sex makeup. While women are traditionally the subjects of research on apparels, my project consciously broke from this mold. I interviewed a roughly proportional group of female and male workers, under the premise that members of both sexes are intrinsic to the garment production process in Kenya, and that both hold valuable perspectives and subjectivities.

All of my interviews with workers were 60 minutes to 2 hours in duration. Interviews were conducted in discreet cafes at a distance from EPZ firms or in workers’ actual homes. Since Kiswahili and English are both national languages in Kenya, most of my interviews took place comfortably in English. On several occasions, however, interviews were done in Kiswahili with help from a bilingual translator.

Interviews generally began with discussion of the tasks that workers perform on the job, the dynamics of employer - employee relations, and workers’ perspectives on working conditions and pay. Here, I was particularly interested in resolving how low-level employees interact with managers, and whether this class of interactions is conducive to information-transfers. Workers were also asked to give their perspectives on the Kenyan labor movement and relay any direct experiences that they have had with human rights activism or labor organizing. This helped me get a sense of some of the alternative information networks that workers are enmeshed in.

After establishing this baseline profile, workers were also asked about their knowledge of the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the end markets for their goods, the retail value of the goods they produce, export-oriented growth models, the geographical location of other EPZs and other garment industries, and their level of familiarity with terms such as “sweat-shops,” “globali-zation” and “multinational corporations.” These questions were designed to glean the type of socioeconomic information workers possess about the global garment industry and the importance of this information to their own selfconceptions.

My final subset of interview questions dealt with the ways in which workers get economic information. Here, I asked my interviewees to describe their levels of contact with local labor activists, unions, local NGOs and international workers rights organizations, and the types of information they gain from them. I also asked workers about their level of viewer ship of local and international newspapers, television programs (emphasis on TV news), and radio. Finally, I asked workers to describe the primary places they obtain information about trade, human rights and the global apparel industry – giving names of places and people where possible.

In addition to interviewing workers, I spent eight hours a week conducting ethnographic participant/observer research in select field sites. A considerable amount of these observations occurred during meetings of the EPZ Workers Association, a grassroots organization led by five former garment workers. I also reported to actual Export Processing Zones each day, interviewing laid-off workers in the mornings and afternoons and interacting with presently employed workers during their lunch hours. Finally, I spent a significant amount of time in the slum communities where workers lived, visiting members of the Export Processing Zone Association in their homes and occasionally conducting interviews. Consequently, although my fieldwork was less extensive than my interview research, it offered me insights on lives of workers outside the factory setting. While my respondents had work experience in a variety of EPZ factories (including factories in Mombasa), the majority of workers I spoke to hailed from a cluster of garment firms in Nairobi and Athi River. Given their centrality to the commentary that follows, these workplaces are described below. Included is information concerning factory location, factory ownership, basic wage rates for permanent workers, factory policies towards Unions, and its reputation among workers in my sample.

FINDINGS ON SENSEMAKING AMONG EPZ WORKERS

My research on Kenyan EPZs indicates that garment workers build their perceptions of EPZ work and global garment manufacture through their positions in production and shop floor hierarchies, their interactions with other EPZ workers within gendered social networks, and their viewership of newsmedia both in the workplace and in the home. As one might expect, these processes of sensemaking are not circumscribed into absolute binaries such as “at home” and “at work.” For instance, sensemaking on gendered social networks occurs both inside and outside the factory and involves a combination of current garments workers, former workers, and family members and friends. My study also reveals that the information which flows down these channels is rich and varied. Workers learn the names of apparel buyers, the cost of finished garments, the geographic reach of apparel manufacture, the volatility of global production chains and trends in global competition. In addition, workers learn about working conditions in other Kenyan factories, forms of resistance that are available to workers, and prospects for the industry at large. Thus, workers perceptions of self and work are bifurcated into the categories “global” and “local.”

Sensemaking on the Shop Floor

As the source of workers’ integration into the global economy, EPZ factory floors play host to an intricate web of production relationships and interactions and are preeminent sites of knowledge acquisition among garment workers. While working laboring on the shop floor, workers learn about the end consumer markets for their goods, the geographical reach of EPZ garment manufacture, and the working conditions facing workers in other countries. Given the patterns in my data, this learning on the part of workers is a function of their company’s organizational structure, its corporate ideology, managerial style, and the ethnicities of its staff persons.

Managerial style has a large impact on learning among workers because supervisors frequently address workers and reprimand them over matters relating to target, production quality, and compulsory overtime. Here, the eth- nicity of supervisors also plays a part in worker learning. Most of the upper level management working in Kenyan garment firms migrated to Kenya from Asian countries with burgeoning garment industries of their own. As a result, many expatriate supervisors juxtapose Kenyan workers with garment workers from East Asia when chastising Kenyans about the shortcomings in their production. These discourses convey a great deal of information to Kenyan workers regarding the geographic reach of EPZ garment manufacture, and workers often internalize the information they acquire through these interactions.

I observed another case of sensemaking-through-reprimand while talking to a Right Choice Pressman named George. When asked about garment manufacture outside of Kenya, George told me: “Supervisors always tell us that Kenya is being paid a lot of money compared to China, Bangladesh, and other African countries. In Africa, we are the highest paid.” Thus, workers at Right Choice acquire much of their knowledge about global garment manufacture while being reprimanded for their ‘poor’ work-ethic, given their ‘high’ compensation.

Variants of this phenomenon take place at other factories as well. At Quality-Tex, a machinist named Jennifer told me that she learned about garment manufacture in Bangladesh because her factory was run by Bangladeshis who compared Kenyan workers to those from their home country.8 Similarly at Pride of Kenya, a male machinist told me he knew about garment manufacture in China, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh because of encounters with managers from those countries. At Pyramid, a female checker also told me she had heard about Bangladeshi EPZs through a line master who confided he had been a machinist in Bangladesh and that there were constantly problems with the power supply.

Although reprimand and managerial discourse are rich sources of global economic information for workers, they are better at conveying some types of information than others. Managerial reprimand always expands workers’ sense of the geography of EPZ manufacture – i.e. garment manufacture in Madagascar, China, Morocco, Sri Lankan, Bangladesh and Uganda. However, more detailed description of foreign industries are often contested. As a worker at Sri Lankan Star informed me:

Despite workers’ skepticism towards narratives that boast of prosperous overseas garment production, these discourses do not distort the realities of global apparel manufacture as much as they disclose truths about garment manufacture under the WTO Multifiber Agreement. Much of the decentralization that exists in the apparel industry is a function of the quotas on apparel export that the WTO enforced prior to January 1, 2005. Under the quota system, garment industry has not been prefaced on perfect competition. Instead, it has been an industry organized around comparative advantage in terms of labor costs and market access.

The fact that these narratives are factual does not mean they are innocuous speech acts, however. To the contrary, narratives on global garment manufacture are often used to silence workers who have job- related grievances – be it concerns about late payment or forced overtime. Narratives on global garment manufacture also allow factory managers to pass their anxieties and insecurities about global integration down to their workers. This mechanism is evident in managerial assertions that garment firms will leave Kenya due to VAT levies and increased competition with China. Given the testimonies of the workers I spoke to, comments like these pervade the shop floor throughout the year, but particularly when there are urgent shipments and lulls in production.

Sensemaking via Institutional Frameworks

Sensemaking through reprimand and casual interaction is not the only form of shop-floor sensemaking that occurs at Kenyan garment factories. Several garment firms in Kenya also have institutional frameworks for disseminating global economic information between management and workers. At Sri Lankan Star, the only Thika Road EPZ with such a system, this infrastructure assumes two forms. First, the management of Sri Lankan Star maintains a bulletin board with current news articles on garment manufacture in Kenya, China, Bangladesh and elsewhere. As a machinist named Catherine told me, information pertaining to garments in China is routinely posted in the company bulletin board.

Secondly, Sri Lankan Star has a workers’ representative program which brings workers and managers together for bimonthly meetings concerning production, external competition, and general industry news. Management meetings are used by the management of Sri Lankan Star to explicitly relay economic information from the Office of the Director down to the supervisors, and then on to the workers’ representatives, who are situated in indi- vidual departments and production lines. According to a machinist I interviewed named Martin, all 2,000 of Sri Lankan Star’s workers are briefed on an issue two hours after the management meeting has taken place.

While Sri Lankan Star’s methods of information transfer are unique among Export Processing Zone firms, they are consistent with an overall corporate culture. Across the board, the management of Sri Lankan Star takes steps to ensure that its workers are personally invested in the fate of the company. These measures include paying workers a salary approximately ten percent greater than other EPZ firms, paying workers when the factory is closed because orders are scarce, and treating the workers more fairly.

Sri Lankan Star’s organizational culture has palpable effects on its workers’ processes of sensemaking. Martin, a Sri Lankan Star machinist who serves as a workers’ representative, had a highly sophisticated understanding of EPZ workers position in global production chains. During our interview, Martin discussed the Multifiber Agreement, the implications of WTO quota expiry for Kenya garment workers, and the production capabilities of garment manufacturers in China, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Although Martin’s knowledge of the global garment industry very nearly exceeded my own, all of his knowledge on these subjects came from the meetings he attended as a workers’ representative, and from his visits to the company bulletin board. For him, the television and news served as only secondary sources for information related to EPZs, although he accessed these newsmedia primarily while at the company.

This trend was true for the other Sri Lankan Star workers I interviewed, several of whom were women. All of the Sri Lankan Star workers I spoke to were at least vaguely familiar with garment manufacture in China, and most of them were also knowledgeable about China and Kenya’s competition for orders. During our interview, a Garment Checker named Mary described China’s tax system and gave me detailed descriptions of China’s investorfriendly labor regime. Meanwhile, a machinist named Catherine commented on the subject: “In China there are a lot of orders, but there is not a lot of order in our companies.”

All of the Sri Lankan Star workers I spoke to were at least vaguely familiar with garment manufacture in China, and most of them were also knowledgeable about China and Kenya’s competition for orders. During our interview, a Garment Checker named Mary described China’s tax system and gave me detailed descriptions of China’s investor-friendly labor regime. Meanwhile, a machinist named Catherine commented on the subject: “In China there are a lot of orders, but here there is not a lot of order in our companies”.

While Sri Lankan Star’s is a unique company, its information infrastructure is not singular within Kenyan EPZs. Pyramid Apparels (Thika Road), Pride of Kenya (Indus- trial Area), Bombay Apparels (Industrial Area) and Safari Wear (Athi River) all have workers’ representatives, and Safari Wear has a bulletin board dedicated to EPZ news articles. Like Sri Lankan Star, Safari Wear also benefits from a generally positive reputation among workers. When asked to describe Safari Wear’s working conditions, one worker offered the following information: “There is a big cafeteria for workers to eat, clean facilities, etc. Everything is under control. The human resource manger doesn’t let Wahindi supervisors abuse workers. On-site childcare services are also provided for workers in need.”

Safari Wear’s favorable conditions can be partially attributed to the presence of the Tailors and Textile Workers Union. As one of the Kenya’s few unionized garment factories, workers at Safari Wear are uniquely endowed with the ability to voice their grievances management via their shop stewards. As one Safari Wear worker informed me, “the union at Safari Wear is very strong. Shop stewards are permitted to leave their posts any time during the day to assist workers.” Workers from African Apparel Experts also praised the role of shop stewards at their companies. Generally, when it comes to handling of grievances and the treatment of workers, the culture of unionized factories and non-unionized factories is very different.

Despite the importance of factory culture, some aspects of sensemaking are standard across Kenyan EPZ firms. One such thing is the centrality of “knowledge-rich” departments like the Finishing Department to shop floor learning. Factory Finishing Departments can be described as “knowledge-rich” because they are a storehouse for information related to apparel sales and apparel trade. Workers in Finishing Departments label all completed garments with company tags and price tags, wrap them in plastic and package them in shipping crates that clearly state the destination of the goods and the company which they belong to. As a result, the Finishing Department can be described as the nexus of sensemaking related to garment commodity chains and their end-consumer markets. Every worker I interviewed cited the Finishing Department when discussing how they acquire their knowledge about garment prices, apparel markets and clothing buyers. Privileged economic information like the names of buyers, the destination of shipments, and the prices of goods travel from the Finishing Department to the rest of the factory via its workers who actively disseminate the information to others. For example, when I asked Jennifer from Quality Tex how she knew the prices of garments made there, she responded: “I have a friend. Also, there was a time that I worked there, in Finishing.” Many workers attributed Finishing Workers’ candidness on these subjects to the Department’s particular labor regime. During an interview, a Pyramid Apparels worker named Grace said the following about workers in the De- partment:

“People in Finishing have the most stressful jobs at the company so you often hear them complaining. They say things like: ‘The management is underpaying us and overworking us! We give them a lot of production and they just pay us peanuts. Yet one piece is costing this amount! That is a lot of pounds!’ Now you see? Other people from other departments, we hear about it.” Grace’s diagram of intra-firm information flows was corroborated by other workers. At Pyramid Apparels, a Pressman named Daniel had the following to say about the Finishing Department, had the following to say about his department:

“Workers in Finishing usually sit down and calculate the profits of the firm. Whenever we get new orders, we multiply the price of each garments by the number of garments we are packing and share this information with others. Therefore workers have their own details, even if they do not visit the Finishing Department themselves.” As another Pressman put it, “Normally, you have to share information that is affecting you. For example, if something happens in production, machine operators have to come and tell us before we ask them. So workers in Finishing also tell other workers before they ask.

Workers also obtain economic information from Finishing Departments by being temporarily relocated there during high-volume production. At Right Choice Garments and Quality Tex, almost all of the workers I spoke to reported being shuffled between different sections of their factory over the course of their careers. Workers are often shuffled from department to department when labor shortages emerge – in some cases transferred from Cutting to Pressing or Production to Finishing.10 Although such experiences left workers feeling objectified, they also helped the workers to augment their knowledge of the global economy: Right Choice employees Alice and Rose got first hand knowledge about the price and buyers of their garments while being stationed temporarily in the Finishing Department. This trend suggests the extent to which Kenyans are simultaneously embedded in mass production processes and transformed into moveable inputs of production themselves.

A final point of continuity in my analysis of Kenyan factory floors is the tendency of information pertaining to EPZ work to accrue along mundane spaces like assembly lines. Within an assembly line, following a strategic “intervention or “insertion” of data, information travels from person to person in the same way that garments travel between machinists on the assembly line. The best evidence for this phenomenon can be found at Right Choice. Workers at Right Choice Garments routinely carry out wildcat strikes when their payments are delayed and these strikes are strategically coordinated via the assembly line. As a machinist named Alice reported: “When strikes take place, announcements are placed in the toilet. When I go to the restroom and see it, I will come back and tell my workmates in Finishing. They will pass the message to the table next to them, and so on, until the message travels across the department and reaches the Packing people. Meanwhile, the same thing is happening on the Production Line. Once someone sees the message, they will pass it up to the next person and the next and the next person. Now, you see that the whole factory is aware, all the workers are aware of what is going on.”

A machinist named Rose corroborated this report, saying: “if you will be found outside, but not the toilet, you will be asked what are you discussing about. So you keep yourself in the toilets whereby nobody can see you. You discuss there, you come back, you don’t work.”

These comments reveal the weaknesses of EPZ management control. Since EPZ firms are hierarchical organizations, management and workers have different toilets— in spite of the fact that this conflicts with the image of the unified corporation that they wish to project. In addition, the production arrangements created by EPZ firms to maximize their efficiency also produce opportunities for discreet communication between workers. Although the movement of goods down assembly lines is unidirectional, the movement of workers is two- directional. All machinists on the assembly line have helpers who carry pieces from their table to the table in front of them, generating a constant stream of back and forth movement. As Alice indicates, garments are not the only things that travel between workers on these trips—information travels as well.

This account also demonstrates the importance of "hidden spaces" to EPZ factory workers: spaces such as factory bathrooms, outdoor grounds, etc. Right Choice Garments is not the only factory where toilets and bathrooms are used to strategically disseminate information to workers. At Blue Nile Garments in Industrial Area, workers use both the toilets and the factory grounds to disseminate information among one another. As one worker reported: “Men hold parliament in the toilet. At parliament you can discuss or announce your intention to strike. At the same time, women at the toilet are discussing issues in their own parliament. Strikes are later coordinated during lunch, or when workers are going home. Here you will find twenty people standing together, discussing together. We manage by physically moving away from the company and our supervisors.”

Like information exchanges that take place in toilets and assembly lines, these practices subvert managerial control and transform public space into private space. In addition, they are acts which exploit the hierarchical organization of EPZ companies. According to my respondents, supervisors are kept separate from workers to such an extent that they have their own eating spaces for lunch and their own toilets. In the end, this separation is precisely what allows workers to covertly organize themselves. This finding supports Chung Yuen Kay’s observation that factory workers create “private spheres” within the workplaces where they adopt patterns of behavior that are otherwise forbidden in their companies (Kay 1994: 212).

Nevertheless, my investigation has also demonstrates that variation exists between firms. While workers at Sri Lankan Star learn about garment production in China directly from their management, workers at other factories learn about it through antagonism and abuse. Similarly, while workers at Right Choice and Blue Nile use their assembly lines to organize wildcat strikes, workers at Sri Lankan Star and the unionized factories in Athi River such incidences are unheard. Thus, sense making among garment workers is ultimately shaped by the dynamics inside their factories.

EPZ firms also breed their own unique systems of knowledge, which can be defined as internally-regulated understandings of the local garment industry and the global reach of apparel manufacture. The existence of firm-specific knowledge systems does not suggest that workers from a given factory have identical understandings, as this assertion ignores the other networks of production and social relation that workers are enmeshed in. However, it implies that workers’ economic perspectives are generally influenced by the particularities of their firms, which include the ethnicity of managers, managerial styles, and information infrastructure and factory environment.

Sensemaking via Social Networks

Information on global garment manufacture also accrues to workers along intra-firm and inter-firm social networks. This form of learning can be differentiated from shop-floor learning because it occurs primarily outside of the firm due to managerial restrictions. According to my respondents, sensemaking via social networks occurs at four distinct times: during their one hour lunch break just outside the gates of their factories, during their walk to work in the morning, during their walk home in the evening, and on weekends – particularly on Sundays where EPZ factories are typically closed.

The first aspect of the social networks specified here is that these networks are usually homogenous in terms of sex composition. Male EPZ workers interact along exclusively male social networks and female EPZ workers have exclusively female networks as well. There was ample evidence of in my qualitative data. For instance, when I asked my male interviewees who they had befriended at their companies, their unequivocal response was “men.” The same was true when I asked male workers who they knew at other EPZ factories and who they worked alongside in their own companies.

Meanwhile, female workers made corresponding state- ments about the gender make up of their social networks. Seemingly, the gendered character of social networks is partially due to the distinctly gendered divisions of labor that exist in EPZ garment firms. Female workers are primarily found in the Production Department where they work as machinists, helpers, checkers and Quality Control personnel on assembly lines. Men, on the other hand, are clustered in the Cutting, Washing and Finishing Departments, and to a lesser extent in Production as “special machinists” and “pressmen.” Even here, however, men and women are spatially segregated. Male machinists and pressman in the Production Department are clustered together in isolation from female checkers and clerks, and Female helpers who work in the male-dominated Cutting and Finishing Departments have different tasks than the men there.

Since men and women occupy different spaces in production, these divisions influence the composition of their social networks. As a worker from Right Choice reported: “Most of my friends are women because those are the people I am working with. We are far away from men. In fact, we don’t even know them, we just see them working. We can’t know what they discuss.”

In addition to gender composition, a second striking feature of sensemaking in social networks is the type of information that workers obtain along them. Unlike sensemaking on the shop floor where workers interpret and process information relating to global garment manufacture, social networks offer workers information pertaining to local as well as global garment production. Here, the content which is exchanged is also specific to the gender character of the networks.

Women informed me that lunchtime, walks to and from work and Sunday visits with friends gave them an opportunity to talk about their jobs with others—particularly issues concerning target, wage, overtime, harassment and treatment of women and balancing of work and family. Using this data, female workers built profiles of their own garment factories and garment factories in other parts of Kenya and spread this information to others—oftentimes as advice for job seekers. Thus, female workers constantly compare EPZ factories with others. As one worker reported: “I have some friends who work at Sri Lankan Star, and on Sundays when we meet and we discuss our jobs. Sri Lankan Stars pays workers well. If you go for a leave, you are paid. When there is a shortage of the job, you are paid while you stay at home.”

Sense making on male social networks conveys both local and global economic information. Groups of male workers discuss issues like international competition, EPZ investment, and government policy in addition to production and factory conditions. As one worker reported, male discussions of EPZ work allow them to “weigh the local apparel industry against the foreign apparel industry.” Through sense making on social networks, men locate themselves on the global production chain and analyze the strengths and weaknesses of their position.

Sensemaking via Newsmedia

Information concerning EPZ work also flows to workers through media sources. Workers learn about global apparel trade and some of the current events that are facing the factory through television, radio and print news. Among my interviewees, workers used newsmedia to learn about WTO Multifiber quota system, the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the rising incidence of capital flight from Kenya, the recent intensification of competition with China, and the potential for the wholesale collapse of the Kenyan garment industry. However, the men I spoke to acquired more of their knowledge about EPZs from newsmedia than women. This is seemingly the result of the division of labor that exists in Kenyan society and most EPZ households.

Whereas Kenyan men are responsible for wage work alone, female workforce participants are responsible for both wage work and household labor. This means that women leave their eight to twelve hour workdays to go home and complete the tasks of cooking, cleaning and childcare. Meanwhile, men are free to spend their time engaging in leisure activities such as watching TV. For example, when I asked a Pyramid Pressman how often he watched the news, he informed me that he watched the news daily despite the fact he did not own a TV – a routine he managed by leaving his wife to do chores while he visited the neighbors:

“Of course, men watch news more than women… You know, a woman cannot abandon cooking or preparing things for tomorrow. But men, sometimes we ignore and we go to our neighbors if we don’t have a TV and we watch there. They [women] want to sleep early and wake up early so in the case of news, unless we tell them if they have interest, assuming that the women have interest in what is happening, But those are educated. They want to know.”

Women’s access to news media is also mediated by their male spouses and relatives. For example, when asked whether workers at Right Choice follow the news, a clerk named Lucy responded: “If your husband is well-off he can buy you a TV. If he is not well-off, then you won’t have one. As for newspapers, I get them from my husband as well. He finishes reading the paper, I go through the headlines.

Since access to newsmedia correlates strongly with the quality of information workers possess about the global garment industry; and since access to newsmedia correlates strongly to the gender of workers, workers’ knowledge of the global apparel industry fundamentally correlates to their gender. Male workers, the primary consumers of newsmedia sources in the EPZs, are generally much better acquainted with the uncertainties currently facing the garment industry. During our conversations, male workers often discussed garment production and global competition using sophisticated economic concepts such as quotas, raw materials sourcing, and full-package manufacturing. This information was pulled directly from the Business Section of the newspaper and passed down along male social networks. A Pressman from Pyramid described this process as follows:

“With the news, many people can be in a position to just watch the news, but if you don’t get from the news you can get it from a newspaper. This is normally what we do. You come with a newspaper and you hide it here, and when you are in the toilet you read it. If not in the toilet, then at lunch time you go through it and you share. You must be educated about the things that are affecting you.” Women’s perceptions of global competition and global garment manufacture draw upon information they acquire on the shop floor and on social networks. Female workers do not discuss volatility in the EPZs in terms of competition with China, international trade policy or vertical integration. Instead, they talk about volatility in terms of sexual harassment, cyclical employment, factory closures and tax. Therefore, although women’s vocabularies on EPZs are limited by their lack of access to newsmedia, their perspectives are rich with insights on the local industry.

Acquiring knowledge vis a vis institutions

Although a variety of worker-centered organizations exist in Kenyan, my research suggest that they play only a limited role in worker sensemaking. Of my fifty respondents, only five workers reported ever having contact with a workers’ rights organization or human rights body. In addition, only one worker had heard the word sweatshop used to describe EPZ work, and this was based on her participation in a Clean Clothes Campaign Labor Panel following the 2003 EPZ Strike. Given the history of the EPZ labor movement in Kenya, this is a surprising finding. The invisibility of civil society actors and the absence of internationalist discourses on labor three years after the EPZ country-wide strike hint at the failure of transnational advocacy networks to take root at the grassroots level. In addition, it suggests a complementary failure on the part of Kenyan civil society organizations to impart information concerning the global labour exploitation and to incorporate workers into the historically significant anti-sweatshop movement.

In the case of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the meager influence that human rights groups have had on EPZ workers’ understandings of their work can be attributed to the limited resources the organizations possess. Take the Kenya Human Rights Commission as an example. Although the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC) has made a concerted attempt to raise awareness around export processing zone workers, the reach of its impact has been severely limited. The bulk of the KHRC’s activities for EPZ workers have been Sunday seminars involving just one or two dozen persons. As far as numbers are concerned, the only exception to this model is the case of rallies; however, such events are not educational and links are rarely maintained.

Despite its rather limited reach, KHRC’s seminars on EPZs have helped garment workers develop sophisticated understanding of global garment manufacture, corporate greed and worldwide labor exploitation.

Curiously, the Clothing and Textile Workers Union (COTU) suffers from the opposite problem. While reaches a lot of workers, it does little to help them understand their position in the global production processes. Union officials in the Ruaraka area specialize in labor rights education. Thus, with few exceptions, they do not spread information about international labor issues to Kenyan area workers. Among the fifty workers I interviewed in Athi River, Mombasa and Nairobi, discussions of garments and labor on an international scope simply did not occur within the Union. Union members were unfamiliar with words like sweatshop and globalization, and knew nothing about labor movement in other countries.

Finally, although several worker-initiated organizations exist, they play a more supportive role in the personal lives of workers, be it emotional support, financial support, or spiritual support. Interestingly, these institutions, a Fellowship and Prayer group, a bereavement fund, and a Round-Robin Group, all originated from Right Choice Garments. Overall, I was impressed with the activeness of workers’ organizations at Right Choice, especially given its harsh work environment. Nonetheless, these organizations do not appear to play a meaningful role in sensemaking among workers.

Factory cultures, collective action and job satisfaction among workers

Although social movement theory predicts that the dissemination of information inspires protest and collective action among workers, this relationship was not present in my data (Keck and Sikkink 1998). Female workers who possessed only small amounts of global economic information were oftentimes more critical of EPZ conditions than male workers who possessed a great deal of global economic information comparatively. As workers learn more about their roles in global production chains, many become paralyzed with anxiety.

Some EPZ companies disseminate economic information to workers for this expressed purpose. Managers at Sri Lankan provide workers with information on global competition, apparel quotas and prospective job losses in an attempt to make them work hard and stay dedicated. According to Martin from Sri Lankan Star: “managers tell workers that if they strive for excellence, then there may be some destiny for the company. It might just be that the company resists the temptation of the quota system.”

This fits into a larger analysis of managerial control in Export Processing Zones. Consistent with Burawoy’s analysis, two factory regimes seem to be in place in Kenyan EPZs; namely a despotic regime and a hegemonic regime (Burawoy 1985). Under hegemonic factory regimes, workers are subjected to less repression and harassment and global economic information is actively disseminated to them. Conversely, under despotic factory regimes, workers are severely repressed and global economic information is monopolized by factory management and disclosed selectively. Thus, hegemonic and despotic factory regimes are really a composite of two variables—managerial style and information infrastructure. Global economic information is constantly being manipulated by the management of EPZ firms. When managers selectively disclose information about the aptitude of foreign workers or the strengths of Asian EPZs, they induces workers’ anxieties and “put them in their place” vis a vis the global garment supply chain. This strategy of control is actively pursued at the despotic EPZ companies. However, this is only a limited strategy. As a machinist from Right Choice reports:

In this situation, the workers’ strike took persisted because of the immediacy of workers’ sustenance needs. The only issue that brings about intermittent strikes in the EPZs today is the issue of stalled payment. Since workers cannot pay rent, buy food or support their families without their paychecks, striking is justified in these cases even though it puts workers’ jobs at risks. At companies where conditions are miserable put payment is prompt, collective action does not occur. This decision not to protest should not be mistaken for job satisfaction, however. Instead, it is an example of workers placing their immediate needs ahead of other considerations.

This negotiation between immediate and long-term need also explains why they endure conditions and hours that are patently unfavorable. Practically everyone I spoke to in the EPZs viewed their jobs in a cost-benefit or utilitari- an framework. At times this was explicit, such as in the comments of Anne, for example, a machinist from Sri Lankan Star. When asked to describe her job, Anne responded: “Ok, now about my job, you can analyze it in two ways. You have the benefits and you have the costs. You liking for that job, and what you don’t like in that job. What would you like to hear first? The benefits or the costs?”

This discourse on cost and benefit appeared in subtler form in many of my other interviews. The workers I spoke to often talked about how their jobs were unpleasant but necessary for their survival, and used phrases such as “daily bread,” and “no alternative,” repeatedly to describe their EPZ employment. Particularly poignant narratives on EPZ work exist among retrenched EPZ workers. One man who had been laid off for two years offered the following comments on EPZ work:

“You know, employment opportunities in Kenya are very low and in the EPZs, you find companies that can carry more than 1,200 workers. If you go to EPZs, you can get hired as a helper, etc.. and you can train yourself inside to be a machine operator and then go somewhere else, you can get a job. That is why so many people come to the EPZs. Many people who are machinists now first got jobs as helpers. As for why

I’m still willing to work in the EPZs, why I’m still looking for a job there -- you know, currently I have no alternative. You know I cannot stay idle.. and because I have an experience as an operator, I have to come and look for ways that I can get inside and get some money for some months.”

Finally, the frequent incidence of strikes at Right Choice makes another point concerning hegemonic and despotic factory regimes. Factories with despotic regimes are less stable than their hegemonic counterparts. This firm-level variation shows the importance of managerial regimes and factory information infrastructure to workers’ participation in collective action. At factories where workers obtain their information through clandestine channels like “Parliaments,” indigenous structures facilitate collective action. Alternately, at companies where information is disseminated to workers on bulletin boards, managerial meetings and announcements, workers lack structures that help them collectively organize.

Having identified the sites where sensemaking occurs among workers, a second question emerges—how do workers interpret and make sense of their position in global production chains? The central finding of my research is two dominant interpretations of labor and work exist. The first interpretation, which seems to predominate among female workers, is that export processing zone garment factories are highly exploitative and undesirable places of work. Meanwhile, the second interpretation, which alternately predominates among male workers, is that EPZ garment factories are volatile and chal- lenging, yet desirable places of work. It is important to consider the differences between these two discourses.

I would tell them that there are a lot of problems” (Catherine, machinist at Sri Lankan Star). “I can advise them to not even come to the EPZ” (Joyce, Machinist at Sri Lankan Star).

“I’ll tell him that there is a lot of work and very little we are being paid” (Mary, Machinist at Sri Lankan Star).

“EPZs are a place where there are no rights of work. They contribute to more sickness than benefit you can get in that very factory as a worker. I can rate it as a second Nyayo torture chamber, where workers are just there, but they work as slaves.” (Grace, machinist at Pyramid [w/translator]).

Female workers in the EPZs also regard on-the-job mistreatment as a local problem pertaining mostly to Kenyans. Although this is not an accurate perception of global garment manufacture per se, it is a perception that is consistent with the ways that knowledge is produced among women workers. My interview data suggest that women acquire much of their information on garment manufacture from gendered social networks where issues like payment, production, working conditions and family are central topics of discussion. Just as these knowledge networks have an inward focus, women’s discourses on work emphasize the effects of garment manufacture on women’s lives. In addition, though shop floors play a secondary role in women’s learning, it seems that the information that women learn here is subsumed by their feelings of harassment when facing managerial reprimand.

An entirely different interpretation of EPZ work exists among my male interviewees. Here, discussions of work emphasize the redeeming qualities of EPZ jobs. When asked to describe his job, Martin from Sri Lankan Star said, “It’s fine, I like it.” Other men claim that EPZ work is “sometimes good, sometimes bad,” and most refuse to state outright that EPZ workers’ rights were not respected.

When I asked a Quality Control personnel named Peter how he felt about the workers’ rights, he responded: “Yes (laughs)… Well… it will take time. It will take some time before rights are recognized.”

Men’s determination to speak positively about their EPZ makes their narratives on EPZ work highly contradictory. For instance, when I asked Daniel from Pyramid Apparels to describe his EPZ factory and EPZ work, he answered:

“My job is only a problem when it comes to target. So I tell others that EPZs are good places to work, it’s only that we have to pump in change. So that these people may be concerned about the needs of workers. Because these investors, they just want to be rich and they forget the workers. But it’s a good place. My factory is good, but they don’t know how to handle workers. They handle workers carelessly.”

Faced with the same question, a pressman from Pyramid responded: “To that person who does not know what an EPZ is, I can tell them it is good sometimes and it is bad. Like when you enter inside, you are being harassed, there is low pay, sometimes delayed pay, you can tell all that to that person who doesn’t know EPZ.” Here, contradiction exists because the respondent begins by qualifying EPZ conditions as both good and bad, but proceeds to list only negative features.

Among my male interviewees, only a handful criticized EPZ work in explicit terms. One such worker was George, a Pressman from Right Choice. When asked to explain what export processing zones are, George answered: “EPZs are BAD. They are not places I can advise others to go. As Kenyans, we just succumb to such work because of the economy and because of the shortage of jobs in the country. But, if it is in a real sense, the EPZs are not a place where there is humanity, where there are good relationship of work, there is nothing to do with anything that can uplift the human standard.” Given the uniqueness of his comments, it is important to note that much of George’s open disdain was partially attributed to the fact that he lost his job at Right Choice one day prior to our interview, and that his wage as a casual there was only 3,999 Kenyan shillings per month, or approximately $55 USD. This is an extremely meager wage, even for EPZs work.

Interestingly, the fact that women and men obtain their information on garment manufacturing from different sources does not completely explain the variation that exists between their two perspectives. Given their methods of sensemaking, men’s perspectives on work are counterintuitive because their discussions of EPZ work exclude talk of labor exploitation, despite the fact that their study of global garment manufacture lends itself to this very analysis. Conversely, while women’s observations of their work heavily center on mass labor exploitation, most female workers lack the knowledge of global garment production that their male counterparts have. Based on the types of knowledge that men’s and women’s sensemaking provide them, one would assume their perspectives would be reversed.

The contradictions inherent in these interpretations of EPZ work are best explained in terms of schema analysis. According to business management theorists, sensemaking does not have to be accurate, but must be “plausible” based on one’s own schemata - or mental codifications of experience (Doughtery and Symthe 2004). This is true for my respondents: self-in-organization schema, person-in organization schema, and organizational schema all help justify male and female interpretations of their workspaces.

For instance, when talking about themselves in the context of their factories, female workers make statements concerning the harassment, fatigue and frustration they experience in the workplace. As workers, they see themselves as vulnerable and exploited. Female workers also make a similar set of classifications when discussing their managers and supervisors. These classifications, which Harris calls “person-in- organization schemata,” consist of a variety of negative statements concerning supervisors’ heavyhanded treatment of workers, and their propensity to harass them sexually. Thus, when it comes to making sense of the organization as a whole, women simply layer their self-in- organization schema and person-in-organization schema on top of one another other to generate an organizational “world-view.”

Men’s interpretations are based on an opposite set of selfin- organization and person-in-organization schema.

Rather than complaining about conditions, men speak of their work as something that wins them daily bread for their families – making them hard workers, providers, and heroes in the context of their organizations. Similar person-in-organization schemata are used to describe management. Unlike female workers, male workers depict their supervisors as hardworking men who are under constant duress from management. Given that these schemata serve as the building blocks for men’s perceptions of EPZs as organizations, it is understandable why men often view EPZs as reasonable places to work.

Performances of gender and gendered understanding of work.

Cognitive schemata do not fully explain workers’ discourses on Export Processing Zones. Workers’ discourses on export work are also linked to aspects of social performance. Men’s contradictory statements regarding EPZ work illustrate this phenomenon. Their discourses on work uphold socially accepted conceptions of masculinity characterized by bravado, euphemisms masking the true strain of the job, as well as paternalistic viewpoints on women’s economic roles. This last case appears primarily among the male spouses on EPZ workers, who often tell their wives that they should opt out of EPZ work and return home. Statements like these construct a fantasy of male breadwinning that ignore the push factors which send married women out of their homes and into global factories in the first place. As Fernandez-Kelly observes in her study of Mexican apparel workers, “women are hardly supplemental wage earners “the size and distribution of their households, as well as the weak employment status of the men in their families, are precipitant factors which explain the entrance of women into the industrial labor force” (Fernandez Kelly 1983: 57-58).

Cognitive schemata do not fully explain workers’ discourses on export processing zones, however. Workers discourses on their jobs garment work are also linked to aspects of social performance. In my data, I detected gender performance in a number of places, particularly in men’s contradictory statements regarding EPZ work. Men’s discourses on work uphold socially accepted conceptions of masculinity are characterized by bravado, euphemisms masking the true strain of the job, and paternalistic viewpoints on women’s economic roles.

This last case appears primarily among the male spouses on EPZ workers, who often tell their wives that they should opt out of EPZ work and return home. Statements like these construct a fantasy of male breadwinning that ignores the push factors which sent married women out of their homes and into global factories in the first place. As Fernandez Kelly observers in her study of Mexican apparel workers, “women are hardly supplemental wage earners. “the size and distribution of their households, as well as the weak employment status of the men in their families, are precipitant factors which explain the entrance of women into the industrial labor force” (Fernandez Kelly 1983: 57-58).

In addition to being counterfactual, men’s narratives on EPZ work and are counterintuitive because women are usually presumed to be the passive and submissive participants of global production. As Pietro attests: “In the maquiladoras they hire women because men created more problems for them. We women are more easily managed. By contrast, a male worker wouldn’t stand for it – he’s more aggressive. Men organize themselves, and if they don’t get what they want, they walk off the job, which really inconveniences concessions” (Pierto 1985: 31). In my study, this relationship is reversed at the most rudimentary level of discourse. Whereas men tend to qualify their ill- treatment in the EPZs, women are aggressive and articulate when discussing their grievances.

Nonetheless, in terms of gender performance, passivity serves male workers well. Claiming to be indifferent to EPZ conditions allows men to perform their masculinity and reject portrayals of EPZ workers as exploited and helpless persons. Consequently, although men’s per- formances do not address the powerlessness or working conditions that they experience daily, they deemphasize and abstract them in an manner that protect their public presentations of self. This finding on discourse and gender performance is supported by the social- psychology literature. As Ezzamel and Willmott state, “identity must be continually reconstituted. Human beings are engaged in a process of constructing, sustaining and restoring a sense of self identity as a continuous reality in the face of circumstances that either confirm or pose a challenge to its narrative” (Ezzamel and Willmott, 1998: 364).

When it comes to understanding global production systems and transferring their knowledge, Kenyan workers rely on schema that betray the reality of gender separation which exists in society. Gender relations, gendered social networks, and gendered divisions of labor affect every step of sensemaking that workers in Kenya undertake. Men’s knowledge of global garment manufacture is derived from the gendered divisions of labor in Kenyan society ranging from garment factories, where men work in information-rich departments such as Finishing Department, to gendered division of labor in their homes, which leave men able to watch TV and pursue leisure activities in the evenings, and including gendered social networks, whereby men discuss news and current events with other men.

Societal gender relations also affect how workers use and process knowledge. While data concerning local and global garment manufacture are available to both men and women, each gender concerns themselves with different spectrums of information. Male workers seek out information on global garment manufacture because it helps them evaluate the future prospects of their jobs and the garment industry more broadly. Meanwhile, female workers seek out information pertaining to local garment manufacture, because it helps them build profiles that can inform their future employment options. This relates to schemata and discourses on work as well – men are presumably more tolerant of factory conditions because they see their fate, and to an extent, their self esteem as dependent on their employment in the factories. Conversely, women workers can be critical of factory conditions because gender roles in society allow them be more non-committal labor market participants.

Imagining Embeddedness: responses to global integration among epz workers