Textiles from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site (based on materials from 2012–2016 excavations)

Автор: Novikov A.V., Senyurina Y.A.

Журнал: Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia @journal-aeae-en

Рубрика: The metal ages and medieval period

Статья в выпуске: 3 т.52, 2024 года.

Бесплатный доступ

The article describes 366 samples of clothing (some of them attributable), collected in 2012–2016 from cultural layers of the 15th to middle 18th centuries at the Ust-Voikary hillfort site in the subarctic zone of Western Siberia. We provide technological characteristics: size, state of preservation, color, properties of threads and fibers, interlacing system, technological errors, cut, and traces of repair. Both animal and plant fibers are present, and plain and twill weaving are attested. Ethnographic and zoological data provide information on the textile technologies used by residents of the polar zone of Western Siberia, and allow us to compare them with those known from other sites. We conclude that types of textiles for clothing remained virtually the same from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Fabrics, mostly woolen, were imported.

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/145147221

IDR: 145147221 | DOI: 10.17746/1563-0110.2024.52.3.091-098

Текст научной статьи Textiles from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site (based on materials from 2012–2016 excavations)

Textiles, as a source, have a rich capacity in archaeological research, since their study reveals both the features of the finished textile product and the technology of its manufacture, and also social and economic factors that influenced the choice of textile fabric or product, as well as the aesthetic and value preferences of a specific society and various forms of cultural contacts.

The entire process of textile production can be divided into several stages: selection and processing of raw materials, formation of yarn and production of threads, creation of woven fabrics using various tools, and dyeing (which can be done at any stage). Additional information on the manufacturing technology of textile items can be provided by historical and ethnographic sources, and analysis of archaeozoological and archaeobotanical evidence, as well as tools for creating textile products discovered at archaeological sites.

By now, a significant collection of samples of ancient textiles from archaeological sites of the late 15th– 19th centuries in Northwestern Siberia has been accumulated. These finds have been studied and described only partially. Textile evidence obtained during archaeological research in 2012–2016 at the Ust-Voikary hillfort site was presented at conferences (Novikov, Senurina, 2016; Novikov, Mukhyarova, Senurina, 2015). This study provides the first full analysis of textile materials from Ust-Voikary.

Description of the collection of woven materials

The study of the Ust-Voikary hillfort site has a long history (Garkusha, 2020). Archaeological works at the site were carried out from 2003 to 2008 under the supervision of A.G. Brusnitsyna and N.V. Fedorova; and from 2012 to 2016 under the supervision of A.V. Novikov. The studies have revealed that the site was a multilayered settlement, which developed from the late 13th to the 19th centuries. These time boundaries were established from the dendrochronological data (Gurskaya, 2008; Garkusha, 2022).

Scholars identify the Ust-Voikary hillfort site with Fort Voikary (Brusnitsyna, 2003; Arkheologicheskaya karta…, 2011: 84, 92; Garkusha, 2020: 142). The first mention of Fort Voikary, going back to 1594, is associated with a campaign by the Koda Ostyak servicemen to the lower reaches of the Ob River, to the outskirts of the town of Voi-kar, whence they brought back several captives (Perevalova, 2004: 39). G.F. Miller mentioned the Ostyak town of Voi-karra: “This town stands on the left bank of the Ob River”, and “the Ostyaks still live there; but the Samoyeds often come there, too” (1787: 205). The ethnic composition of the settlement’s inhabitants has not been definitively established. However, taking into account the ethnic history of the region, this population can be tentatively considered Ugro-Samoyed with a Komi-Zyryan component (Martynova, 2005; Perevalova, 2004: 231–233).

Permafrost ensured good preservation of items made of organic materials at the site. During the excavations, an assemblage of textile materials and items required for fabric handling (thimbles, needle cases, needles, cutting boards, and a spindle-type tool) was collected. The fabrics discussed in this study were discovered during the examination of cultural layers dated to the mid-15th to mid-18th centuries (Garkusha, 2023) at the Ust-Voikary hillfort site in 2012–2016.

Textile fragments were found both in the interdwelling space and inside the buildings. In total, 366 fabric samples were studied, which is 96 % of the textile materials (the collection also included fragments of felt, ropes, and threads; knitted items were absent). The technological study of the textiles included visual examination, analysis of the samples and their structure by the methods of materials science, a search for technological parallels, and reconstruction of the manufacturing methods.

The studied samples were of different shades of brown, red, or green. However, note that during the time when the samples were in soil, their color (differently for different materials) could have been changed significantly by biochemical factors. Some brown samples might originally have been dyed red, and green samples could well have been blue. The chemical composition of the fabric dyes was not determined; but in some cases, colored fibers were detected using optical microscopy.

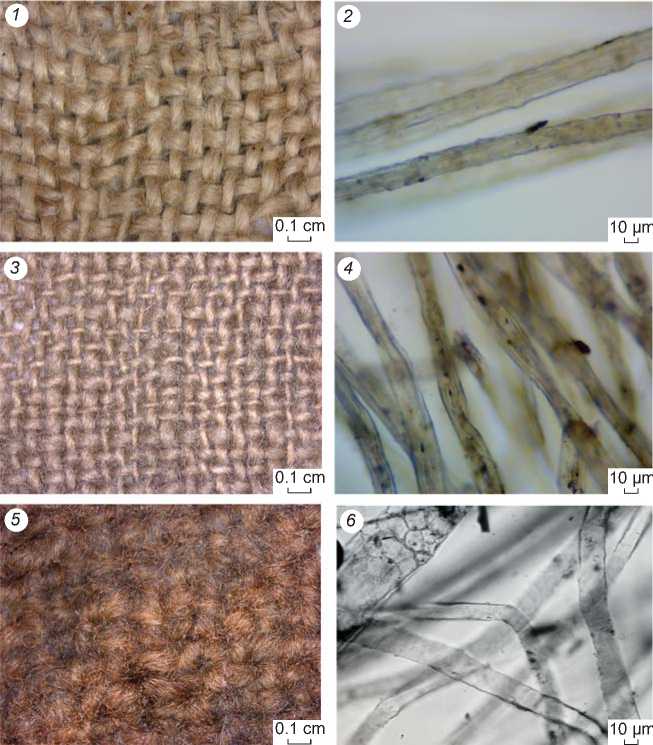

According to the type of raw material, the fabrics from the collection can be divided into two groups: those made of raw materials of plant origin—bast and cotton fibers (Fig. 1, 1–4 ); and those made of raw materials of animal origin—wool (Fig. 1, 5 , 6 ). Fabrics from plant fibers included only two samples; all the rest were made of wool.

In terms of structure, the discovered fabrics can be classified as plain weave and twill weave. Plain weave is typical for fabrics from plant fibers. Woolen fabrics are distributed depending on the type of weave as follows: plain weave fabrics – 331 samples; twill weave – 21 samples; indeterminate – 14 samples.

The major part of the textile collection is plain-weave fabrics. It is one of the basic weaves with the repeat pattern limited to only two threads and two passes: each warp and weft thread alternately passes over one thread of another system and under the next thread; odd and even threads are opposite at each pass (Ierusalimskaya, 2005: 34). Woolen fabrics of plain weave include woolen cloth and broadcloth. In woolen cloth, unidirectional twist threads (Z/Z or S/S) are used in the warp and weft; there is no underlay. In broadcloth, multidirectional twist threads (Z/S or S/Z) are used in the warp and weft.

Woolen twill fabrics in the textile collection from Ust-Voikary include only a small number of samples. Twill weave, like plain weave, is considered basic. Diagonal lines are formed on the surface of twill textile by a special order of alternated warp and weft threads: the first warp thread overlaps the first weft thread; the second warp thread overlaps the second weft thread, etc. (Ibid.: 38). In the Ust-Voikary fabrics, the twill repeat pattern is 2 warp threads to 2 weft threads (2/2 twill). Twill wool fabrics are included in the wool twill group; they have unidirectional twist threads (Z/Z or S/S) in the warp and weft; only two samples have threads of opposite twist (Z/S or S/Z).

Woolen fabrics of plain and twill weave of the 15th–18th centuries are known in Northwestern Siberia from the evidence of the following sites: the Chastukhinsky Uriy and Ust-Balyk cemeteries, the Endyr-1 fortified settlement, and the Endyr-1 and Endyr-2 cemeteries, as well as the Mangazeya, Berezovo, and Staroturukhansk fortified settlements (Glushkova, 2002: 45–55; Katalog…, 2013: 24–34, 55–57, 60; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: 76–77, 228; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, Kurbatov, 2011: 182).

In the fabrics from Ust-Voikary, it was often impossible to determine the weft and warp threads owing to the absence of edges and a number of other features. A large number of technological errors have been observed

Fig. 1 . Microphotographs of textiles. The Ust-Voikary hillfort site.

1 – fabric made from plant fibers (bast fibers); 2 – bast fibers (×400); 3 – fabric made from plant fibers (cotton fibers); 4 – cotton fibers (×400); 5 – woolen fabric; 6 – wool fibers (×400).

during the study of archaeological textiles from Ust-Voikary. In 23 % of samples dating back to the late 15th – 17th centuries, there are identical weaving errors, which in some cases may reflect specific features of looms. During manual feeding of threads, errors may occur in any weft row resulting from incorrect thread grip: when working with one shed, they are possible only in the row where manual feeding takes place, and in the presence of heddle thread loops, errors may occur because of failure in threading warp threads into thread loops (Glushkova, 2002: 107–109, 125; Orfinskaya, Mikhailov, 2020: 53).

Two types of textile errors were observed in the textile evidence

0.1 cm

0.1 cm

0.1 cm

10 μm

10 μm

from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site: doubled warp or weft threads throughout the entire row; and overlapping of threads of one system with two or three threads of another system. The former error can be considered a technological error in weaving caused by unfastened warp threads, or a broken weft thread (Glushkova, 2002: 46; Orfinskaya, Mikhailov, 2020: 53). The second error may be associated with manufacturing fabric on a vertical or horizontal loom in which warp threads were not rigidly fixed with special devices (Glushkova, 2002: 46). Identical weaving errors may indicate that the textiles were made in a single production-center.

No weaving tools or devices were found at Ust-Voikary, which suggests the absence of manufacture of threads and fabrics in this region. However, it is noteworthy that the evidence studied comes from only a part of the site. Tools associated with textile production, such as needles and thimbles, have been discovered, which suggests that the locals sewed and repaired their clothing themselves.

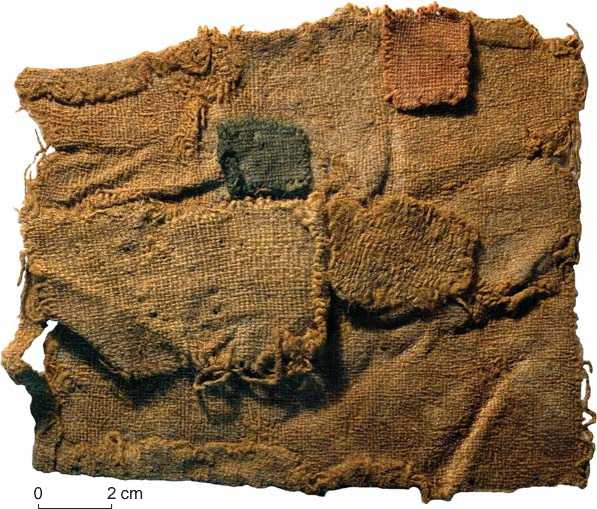

The analysis of clothing fragments from the collection has shown that the edges of the items were sometimes left unprocessed or were folded with a fold height of 0.5– 0.7 mm; a double fold with a closed edge was made. Items with unfolded edges or with small folds (aimed at saving the fabric) were possibly made directly at the Ust-Voikary site. The items that had standard processing of textiles could have been brought from other areas where there were no problems with the fabrics. The great number of patches on the items also indicates careful treatment of fabrics (Fig. 2). All patches, square or rectangular, were sewn on the inside of the outfit.

Discussion

In the evidence from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site, textiles appear mainly in fragments. Only 65 samples show traces of sewing, and can be associated with fragments of sewn products. Only one item—a cotton scarf—is suitable for complete identification. Therefore, despite the large number of woven samples, it is not yet possible to reconstruct specific varieties of clothing.

Some textile materials were found in buildings, and can be synchronized with wooden structures. The evidence found in the inter-dwelling space was considered as textiles used by the dwellers from the mid-15th to mid-18th century.

Fig. 2. Fragment of textile item with patches. The Ust-Voikary hillfort site.

Forty nine samples of textile were found in the 17th-century dwellings. The technological features of three samples have not been identified. Fabric is divided into the following groups: 1st – thin cloth; 2nd – thin woolen twill with unidirectional Z-twist threads (errors in the fabric); 3rd – thin woolen fabric with unidirectional Z-twist threads; 4th – medium cloth; 5th – medium woolen fabric with S-twist threads; 6th – medium woolen fabric with Z-twist; and 7th – thick cloth. Samples of fabric produced with weaving errors constitute 26.5 % of fabric fragments that were found in the 17th century buildings.

Nine fragments of fabric were found in the 18-century buildings. They can be classified as follows: 1st – thin broadcloth; 2nd – medium woolen cloth with unidirectional Z-twist threads; 3rd – medium woolen cloth with unidirectional S-twist threads; 4th – medium woolen twill with unidirectional Z-twist threads; and

Forty-eight samples of textiles were attributed to the 15th century. One of these was identified as thick woolen twill; one sample was not identified, and the rest belonged to the woolen-cloth group. Twill textile was made with errors in the weaving pattern. The errors were not systematic, which suggests manual feeding of threads in a possible attempt to reproduce the weave of the fabric threads not typical for that particular production area. Plain-weave fabrics are divided into following groups: 1st – thick woolen cloth with unidirectional S-twist threads; 2nd – medium woolen cloth; thick broadcloth, and 3rd – medium broadcloth. There are no thin fabrics. Samples of fabric created with technological errors amount to 39.5 %.

There are 80 samples of fabric attributed to the 16th century, of which the technological features of six samples have not been identified. Thin fabrics are present (7 samples), including: 1) thin broadcloth; 2) thin woolen fabric with S-twist threads (1 sample with weaving errors), and 3) thin woolen fabric with Z-twist. Medium fabrics (37 samples) are divided into the following groups: 1st – medium woolen twill with unidirectional Z-twist threads; 2nd – medium twill with unidirectional S-twist threads (presence of errors in the fabric); 3rd – fabric made of raw materials of plant origin. Thick fabrics are classified as follows: 1st – thick woolen twill with unidirectional Z-twist threads; 2nd – thick fabric with unidirectional S-twist threads; 3rd – thick broadcloth. Fabric samples made with technological errors make up 25 %, which is 14 % less than among the 15th-century fabric samples found in the dwellings.

5th – thick woolen twill with unidirectional Z-twist threads. There are no fabrics with technological errors.

Fabrics made from plant fibers, dating back to the 16th century, were represented in the collection by two samples. Samples of plain weave fabrics dominate among the materials of the late 15th–17th centuries. Samples of twill-weave fabrics are dated mainly to the early 18th century. The number of technological errors in the fabrics becomes noticeably reduced by the 16th century, and no errors have been found in the fabrics of the early 18th century. Textile materials from the layers of the late 15th–mid-18th centuries demonstrate that the population living in this area used mainly woolen fabrics of plain weave.

To study the problems of raw material supply for the manufacture of fabrics by the inhabitants of the Ust-Voikary hillfort site, we should use different sources. According to archaeozoological studies, a single astragal found at the site belonged to Capra et Ovis* . Probably, the inhabitants of the settlement did not breed small ruminants. Ethnographic evidence contains information that “the following domestic animals appear in greater or lesser quantities among the ethnic population. Dogs, horses, cows, sheep and deer are found in greater or lesser quantities. However, sheep… are very rare. They are kept by those Ostyaks who have the opportunity to keep cows in their households” (Dunin-Gorkavich, 1996: Vol. 3, pp. 116–117). Dogs were of great importance to the indigenous population of Western Siberia in all places. As A.A. Dunin-Gorkavich noted in his diaries, which are kept in the archives of the Tobolsk State Historical and Architectural Museum-Reserve, “for a reindeer herder, they are shepherds of reindeer herds; for a hunter, they are indispensable companions in the trade both as trackers and as working animal pulling a sled with provisions behind; in a household, they are a workforce which the indigenous person uses when he needs to transport water, firewood, hay, luggage, etc. As a result, the indigenous people treat dogs with care, and the Ostyaks have developed precise concepts about the features that determine the merits of a dog” (Novikov, 1999). However, it is important to emphasize that despite the diversity of dog functions in the traditional culture of the indigenous population of Northwestern Siberia, none of the scholars has mentioned the use of dog wool as raw material for weaving. Ethnographers have not mentioned processing of wool materials and spinning of wool as a traditional occupation of the Khanty and Mansi in Northwestern Siberia. On the contrary, it is asserted that “the above-mentioned peoples do not spin on their own and do not have their own native material, that is wool, for such yarn” (Sirelius, 1907: 41). U.D. Sirelius wrote that “the Sosva Voguls make their ribbons from yarn obtained from stockings that they buy from the Zyryans” (Ibid.).

Thus, specialized animal-breeding for producing woolen yarn was not typical for the indigenous population inhabiting the northern part of Western Siberia. Sheep and goats were kept in very small numbers, and usually in Russian towns. It can be argued that the traditional economy of the indigenous population in the north of the region did not have a material base for the mass production of woolen fabrics. Such fabrics had been known in this area since the Bronze Age (Glushkova, 2002: 64); yet, since there was no raw material for their production, it may be assumed that most of these fabrics were imported.

Paleobotanical studies of cultural deposits at Ust-Voikary has shown that plant communities in the area of the site were typical of the northern taiga subzone. The Ust-Voikary population used local plant resources only for construction, as well as medicinal and food purposes (Zhilich et al., 2016, 2023), but they cannot be considered raw materials for fabric manufacturing. Thus, there is every reason to believe that the Ust-Voikary dwellers did not have their own animal or plant fibers for manufacturing fabrics. Moreover, no tools for manufacturing woven fabrics were found during archaeological works at the site.

According to ethnographic descriptions from the 17th–19th centuries, the Khanty people used grass, reeds, and nettles in their everyday life. “Mats and small round rugs are made from unscutched sedge. Insoles are made from couch grass and are inserted into winter footwear. Carpets are woven from reeds. Threads are spun from nettle and canvas is woven” (Dunin-Gorkavich, 1996: Vol. 3, p. 92). Women “weave canvases from nettle fiber, sew shirts, embroider with colored woolen threads, and the rich can embroider with silk threads. They weave mats for beds from grass” (Opisaniye Tobolskogo namestnichestva, 1982: 167). Sirelius recorded the use of nettle, hemp, and flax by the Khanty and Mansi. Nettle “is not widespread throughout the entire area where these peoples live. Along the Ob and Irtysh within the Ostyak lands, it occurs in the north almost up to Berezovo or approximately up to 65 degrees of north latitude; and then it gradually starts to be encountered less frequently, until finally it disappears entirely… In the area of the sources of the Vakh, it should not be found either. People say that previously it was not found even at the mouth of this river and that it first appeared there only when the Russians began to cross the river on horseback on the ice. The growth of nettle is the most abundant along the Irtysh, Demyanka, Konda and Salym” (Sirelius, 1906: 18). Sirelius observed that “hemp is currently known everywhere and is an object of trade, but earlier it was probably found only on the Konda… Flax is less widespread, but recently it began to be cultivated on the Konda” (Ibid.).

Historical and ethnographic studies mention traditions of making fabrics and clothing in Northwestern Siberia among both the indigenous and incoming (Russian) population, as well as significant import of textiles (Klein, 1925, 1926; Bakhrushin, 1952; Boyarshinova, 1960; Bogordaeva, 2006; Vilkov, 1967; Lukina, 1985; Prytkova, 1952, 1953, 1961a, b; 1970a, b; 1971; Sokolova, 2009; Syazi, 2000; Fedorova, 1978, 1993, 1995; Fekhner, 1956, 1975, 1977, 1982). Their own technologies for fabric manufacture among the indigenous population of Northwestern Siberia probably started to spread in the 18th–19th centuries, under the influence of traditions of the population arriving from the Eastern European regions. Before that time, the appearance of fabrics from both plant and animal fibers among the indigenous population of the region could only derive from imports. Incidentally, the remoteness of the northern regions of Western Siberia from political and economic centers, and the lack of convenient communication routes with them, did not hamper active trade with the European part of the Russian Empire.

In this regard, information from of the customs books of Siberian towns is of great interest. According to the published data, linen, silk, and woolen fabrics were imported to the north of Western Siberia. For example, linen fabrics, making up 41 % of the total amount of textile goods, were imported to the area of Berezovo. The share of woolen fabrics was ca 47 %, and silk fabrics 11 %. Most likely, goods of poor quality were imported for sale to the indigenous population of the northern territories. For example, in 1687/88, the customs book recorded that “forty-six used shirts [costing] four rubles and twenty altyns, and thirteen used kaftans [costing] five rubles and two grivnas” were imported to Berezovo (Tamozhenniye knigi…, 2004: 77).

As noted above, fabrics (even woolen) in the collection from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site were made with a large number of errors. Taking this into account, it can be assumed that owing to the lack of raw materials and necessary equipment, the local population did not make textiles, but used imported fabrics (or ready-made clothing).

Conclusions

The textile collection from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site consists of plain-weave woolen fabrics, twill woolen fabrics, woolen fabrics with uncertain technological features, linen fabrics made of raw materials of plant origin, felt, ropes, and threads. The absence of knitted items in this collection is noteworthy, even though items knitted with a single needle have been known in Northwestern Siberia since the 17th century. Socks, stockings, and mittens knitted with a single needle are a part of archaeological collections from the Russian sites such as Berezovo and Mangazeya fortified settlements (Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, 2008: 227, 229; Vizgalov, Parkhimovich, Kurbatov, 2011: 184, 188). This may have been caused by the absence of a tradition of knitting clothes among the indigenous inhabitants of the northern regions.

Although items made of organic raw materials have been very well preserved in permafrost, textiles made of plant fibers were found in very small quantities at Ust-Voikary; most likely these were very rare. A small number of samples are thin woolen fabrics of uniform density. Owing to the high cost resulting from the remoteness and inaccessibility of the area, fabrics made of plant fibers and thin woolen fabrics were not thrown away but were carefully preserved.

A significant part of the collection consists of fabric samples made of medium and thick threads. Fragments of woolen fabrics are especially numerous, amounting to about 300 specimens, or 80 % of the total number of finds. Thick and medium woolen fabrics were widespread for obvious reasons. The population of the northern regions of Western Siberia needed warm and windproof clothing made of thick textiles with lining, and multidirectional Z- and S-twist threads provided good density. The absence of whole items among the evidence from the site can be considered a sign of the careful treatment of fabrics. Most likely, the clothes were repeatedly re-sewn until they wore out, and then the remains of the fabric were used for patches. The special attitude to fabrics, and the absence of tools for spinning and weaving among the evidence from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site, demonstrate that textiles were not made on site but were imported.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out under Project FWZG-2022-0005 “Research of Archaeological and Ethnographic Sites in Siberia of the Period of the Russian State” of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the SB RAS.

The authors express their gratitude to O.V. Orfinskaya, Senior Researcher at the Center for Egyptological Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, for her help in the analysis of textiles from the Ust-Voikary hillfort site.