The central choirs singers’ social status, everyday life and moral customs in the Russian state of 16th-17th centuries

Бесплатный доступ

The article continues the study of the social status and related features of the life and activity of the professional Tsar’s and patriarchal choirs’ singers. According to the author, the totality of the installed data (activities, principles of recruitment, types of salary and salary system, legal status) indicated that the Tsar’s and patriarch’s choristers were included in the category of service class people (“sluzhilye lyudi”). Retiring from the choir, they often entered or transferred to such positions or ranks in the state apparatus, such as duma or department diaki, boyar’s children. The obtained data on the peculiarities of every day life and morals, behavior in home life and society allow to specify the social status of these masters.

Mоscow state, service class people, tsar's singing diaki, patriarch's singers, social identification, life and manners, customs

Короткий адрес: https://sciup.org/147233406

IDR: 147233406 | УДК: 783(470.5) | DOI: 10.14529/ssh200212

Текст научной статьи The central choirs singers’ social status, everyday life and moral customs in the Russian state of 16th-17th centuries

The study of the most important professional characteristics of the Tsar’s and patriarchal choirs’ singers (activities, principles of recruitment, salary system, legal status) showed that they belonged to the category of service class people [14; 15]. Thus, the obtained data allowed to clarify the social status of these masters of church singing art, which researchers often refer to the category of clergy. Here we will continue to consider their status and related moral ideas and customs, behavior in home life and society. Some of these phenomena were studied in relation to the entire population of Russia in the 16th—17th centuries [ex.: 10; 11], but in relation to this category of service class people, they were not specifically considered [17].

Most of the time singers of the main Russian choirs of that era were likely to spend serving. In the Tsar’s and the patriarchal courts there were special singers’ “chambers”, where they spent their spare time. The best-preserved documents of the patriarchal decrees depict everyday life of singers in the following way. For diaki and podiaki in the patriarchal choir there were separate rooms, which were called in different ways during the 17th century. The sources mention: “the chamber where the major podiaki live“ (1626), “the chamber where the singing diaki live” (1650), “the chamber in the patriarchal choir where the podiaki live” (1667), “the singing diaki’s cell” (1667), “the podiaki’s rear cell” (1670) etc. [12, v.1, p. 950; 19, № 28, fol. 442; № 60, fol. 298; № 73, fol. 344; 20, № 43, fol. 119]. Near the singers’ chambers there was “a storeroom” and “a closet”, where chant books were kept [19, № 122, fol. 319) 1. The interior of the chambers was modest.

From time to time new benches, tables, candles, icons, micaceous “window frames” and other things were bought for the place [19, № 28, fol. 442; № 92, fol. 388; № 93, fol. 102, 200; № 147, fol. 387; etc.]. Repairs of stoves, doors, bars (bolts) took place as well [19, № 60, fol. 298; № 75, fol. 396; № 81, fol. 356; № 92, fol. 388]. In their chambers singers had a rest and worked. Here they also quite often got “food and drinks” and wrote chant versions for choir. For teaching young podiaki to read and write and the art of chant, apparently, there was another room used, for example, in the 1620-s — “in the basement under the vestry” (12, v. 1, p. 923]. The order in the singers’ chambers was maintained by caretaker or at the end of the 17th century — by a “keleinik” (helper in cell) [19, № 28, fol. 42; № 36, fol. 42; № 38, fol. 34; № 137, fol. 94].

Quite often young singers were accepted in choirs being very young2. Before coming of age and marriage they lived in their father’s family. If chanters were recruited from remote locations far away from the capital, then they were sometimes given a permission to visit their relatives. Thus, in March 1664 the diak of the Tsar’s choir Semen Sidorov was permitted to go to Suzdal “to visit his relatives”; Tsar’s chanter Nikita Nesterov in February 1666 went to “Shatsk to his relatives”. Both of them were given money for the trip (3 and 5 roubles) [27, v. 23, p. 466, 699]. In January 1673 two Tsar’s choir stanitsas of young diaki from Novgorod were permitted to visit their relatives in Veliky (Great) Novgorod [27, v. 23, p. 112].

Support and care on the part of singers about their immediate families were a common practice, and the authorities regarded it with favour. In 1661 the widowed sister of Tsar’s singing diak Andrey Anisimov at request of her brother was given 7 quarters of rye; podiak Afanasy Klimov in July 1671, “at the wedding of his sister”, by order of the patriarch was given a quarter of malt, half-quarter of flour; in December 1673 three young the Tsar’s diaki from Novgorod were given kindiak (a kind of silk cloth) “from Persian goods” for their mothers; in 1678 chanter Ignaty Minin was given 10 roubles by the Tsar “for his sister as the marriage portion”, for Ivan Yudin’s sister — various fabrics and 2 moroccos [20, № 22, fol. 314; 23, № 331, fol. 62; 25, fol. 57; 27, v. 21, p. 1001; v. 23, p. 190]. After the death of krestovy diak Prokofy Nikitin, his son Ivan in 1680—81 was admitted to replace his father in his position, for him “to maintain his mother and brothers” [22, № 21101, fol. 1—5]. Here the salary of a diak is a main means of support of his immediate relatives. The singing diak Zakhary Glomozdinsky’s brother Stepan was learning the craft at the master of Golden Palace at his brother’s expense [4, p. 42]. In case of death of any singer’s relative the singers asked for monetary aid for the funeral rites, and sometimes for the funeral repast. In October 1665 a diak of the Tsar’s choir Nikita Nesterov was given 10 roubles for the funeral of his father; podiaki Avraam Pavlov, Matvey Yakovlev, Matvey Tashlykov and others in the 1670—80-s were given 1—2 roubles each by the patriarch for funerals of their mothers [19, № 92, fol. 318; № 102, fol. 293; № 108, fol. 285; 23, № 1073, fol. 49]. The Tsaritsa’s krestovy diak Yakov Korsakov in October 1680 was given 10 roubles for the funeral repast of his brother, who while alive had a noble title of groom [22, № 19714, fol. 1].

Singers, who were joining the main Russian choirs from remote locations and towns, and those who already had their own families, after the audition and acceptance to the service moved their families to Moscow right away. In September 1652 the patriarchal singing diak Nester Ivanov left for Veliky Novgorod “to take his wife with him”; from the treasury he was given 5 roubles for the trip [19, № 34, fol. 223]. The Tsar’s singing diak Andrey Nizhegorodets in January 1691 went to Nizhny Novgorod “to take his wife and children”; he was given about 4 roubles for the trip and for the carriages [28, p. 294].

Young diaki and podiaki were getting married, as a rule, when they reached the age of 15—16 years. Many of them could not cover the considerable expenses on wedding and had to resort to the support from the treasury and count on payments. Thus, the Tsar’s krestovy diak Ivan Vasiliev in October 1639 was given cloth for his wedding kaftan [23, № 295, fol. 19]. In October 1652 patriarch Nikon gave 5 roubles to podiak Matvey Kuzmin for the wedding “because of his poverty” [19, № 34, fol. 225]. But then all singers who were getting married began to be given that amount of money; since the second half of the 1660-s it decreased to 3 roubles, but the singers were also given flour, cereals, malt and sturgeon [19, № 34, fol. 233; № 43, fol. 237; № 54, fol. 116; № 64, fol. 261, 275, etc.; № 140, fol. 326, 349; 20, № 22, fol. 37, 52, 240; etc.]. Wedding feasts of the Tsar’s singing diaki were celebrated, apparently, in a bigger way than weddings of the patriarchal singers. For example, the Tsar’s choir diak Andrey Anisimov for his wedding in January 1668 was given 2 buckets of wine, a hog carcass, 2 geese and 2 piggies; Ignaty Minin in January 1675 was given 10 roubles for his wedding [27, v. 21, p.1378—1379; v. 23, p. 369].

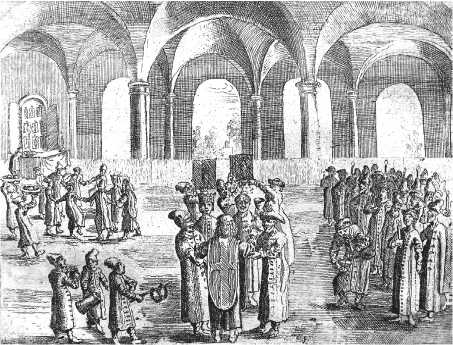

Performing a wedding ceremony. 17th century engraving [13, p. 215]

Evidently, a singer had to announce his will to marry in a petition addressed to the Tsar or the patriarch and to ask for permission. In 1674 the Tsar’s diak Nikifor Simonov wrote, that he “persuaded” a daughter of Gos-tinaya sotnia’s (a privileged corporation of merchants) tradesman I. Khokhlikov from Yaroslavl to marry him. She lived in Moscow at her uncle’s place, was visiting her mother and step-father in Kadashevskaya sloboda, but was not registered as one having some “Tsar’s profession”. The diak asked permission to marry her: the time came after the engagement [9, p. 244—245].

Sometimes the court was trying to find a wife for a Tsar’s diak, and the Tsar took part in that, too. Agrafena was proposed to Luka Alekseev as a wife. As a little girl in 1653—54 she was brought from Poland by her father, “a Hebrew foreigner”, and after being converted to the Ortodox faith she lived at the Tsaritsa’s court [9, p. 245]. By the Tsar’s “decree” diak of Aptekarsky (Pharmacy) prikaz Zot Popov in January 1673 “married off” his singing diak Dmitry Tveritin and on behalf of the Tsar presented the fiancé with a silver ladle [27, v. 23, p. 113].

The birth of children in chanters’ families was celebrated as a joyful event. In November 1671 podiak Pavel Ivanov in connection with the fact, that “his wife gave birth to a child”, was given fifty copecks by the patriarch; in 1672 the diak of the Tsar’s choir Savva Arkhipov was given a bucket of wine “for his son’s christening”, and the Tsar’s singer Feodor Rostovets on a similar occasion — 2 buckets of wine; in January 1674 the Tsar’s krestovy diak Peotr Pokrovets “for his daughter’s christening” was given 2 buckets of wine, 3 buckets of mead, 5 buckets of beer, 2 geese, 2 ducks, a turkey-hen and 2 chickens [19, № 75, fol. 287; 27, v. 21, p. 1595, 1697].

The upbringing of children took place in the family; sons were usually prepared for public service. The head of the family always was a highly educated man. His profession required good knowledge of divine service books and mastering the most complex systems of writing of the Old Russian chant works. Quite often, as was mentioned above, a singing diak or podiak acted as a writer-scribe, draftsman (petitions, explanatory notes, protégé cases) etc. Since the 1680-s of the 17th century young singers began to be taught foreign languages. Under the patriarchal decree of June, 17, 1681 in the yard of the Book Printing Prikaz Manuil Mendilinsky, “a Greek”, taught podiaki and other students “the bookish variant of the Greek language”, and students “without kith or kin” were given 3 “dengi” (1,5 copecks) per day [19, № 102, fol. 89—90]. In 1680—90-s singers were mastering oratory. For many years they were taught feast “orations” by one of the outstanding representatives of the Russian intellectuals of the 17th century, the editor of the Printing House Karion Istomin [19, №108, fol. 190; № 111, fol. 162; № 127, fol. 185; № 137, fol. 213; etc.].

In this way, professional chanters of the main choirs of the medieval Russia were quite educated people1. Their children could easily learn the basics of literacy from them, especially their sons, who often were in the track of their fathers2. The most talented youths in the second half of the 17th century had the possibility to continue their education. Podiak Afanasy Saveliev’s son Osip became well-known in the court of the patriarch owing to his greeting speeches which were delivered by him every year from 1677 to 1680 on Christmas and Easter [19, № 89, fol. 296; № 92, fol. 248, 249; etc.]. In 1681 he was sent to school of the Book Printing House to study “the high sciences”, “the Greek and Slavonic book writing”, and since 1685 he improved his knowledge in Kitai Gorod school of Likhud brothers [19, № 115, fol. 245, 250, 262; № 137, fol. 213 etc.]. The patriarchal singing diak Semen Nizhegorodets’s son Nikolai has a similar story. By 1692 he had learned “Hellenic and Greek languages”, could translate “into Slavonic language, and from Slavonic into Helleniс and Greek” [31, p. 34]. Signatures in lists of salaries, which due to this or that reason were given to the singers’ sons instead of their fathers, also testify that the youths were educated. That fact allowed them to take public service. Thus, in 1684 after the death of the Tsar’s singing diak Luka Alekseev his widow asked the Tsar to accept her son as a minor diak of Masterskaya palata (a department responsible for the Tsar’s garments) [25, fol. 18—19].

Daughters in families were, first of all, meant for married life 3. Marriage was a great event in a family. Sometimes on behalf of the Tsar or the patriarch payments were given to be used as “marriage property”. In 1633 the daughter of krestovy diak Mikhail Ustinov, girl Varvara was given 10 arshins of damask for letnik (a light women’s garment with long and wide sleeves) and 5 arshins of bagrets (precious scarlet fabric) for opashen’ (a garment with arm length or longer sleeves, wide at the top and narrowing towards the end); bagrets for opashen’ was also given in July 1644 to the Tsar’s singer Semen Samokhvalov’ daughter [23, № 88, fol.

127; № 299, fol. 82]. Parents tried to marry off their daughters to men “of the same social position” or representatives of classes related to singers. For example, the Tsar’s choir diak Pavel Agapitov’s daughter became a wife of the same choir’s singer Savva Arkhipov. Pavel’s widow handed over the yard to the young [22, № 17440, fol. 8]. The patriarchal singing diak Vasily Kononov’s daughter married the priest of the Church of Exaltation of the Cross, situated behind the Sretenskie Vorota (Gates) [19, № 134, 91—92].

The financial state of professional singers serving in the main Russia’s choirs was far from being equal. As far as we know, the art of chant attracted both manor or shop owners and the taxable inhabitants of the medieval town (“posadskie tyagletsy”). The singers had different salaries; some of them for a long time worked without getting salaries [14; 15].

Of course, the main means of living for most families was salary, fixed for singers on service (money, bread, meat, cloth, etc.). Often on some occasion singers were given monetary payments. The available documents of the second half of the 17th century mention occasional distribution of food products to singers — peas of different sorts [27, v. 21, 1134—1135, 1588 etc.] 4, wine (from 3 buckets to one quarter), honey (from 3 poods and less, “instead of wine”), chicken and fish (sturgeon, salmon) [19, № 140, fol. 329 etc.; 27, v. 21, 1185—1186, 1595—1596, 1600, 1710]. Apart from whole sets of garments, which were regularly given to singers from the treasury, as we can judge by the documents of the first half of the 17th century, members of their family could also be given separate pieces of clothing at the expense of the treasury. From time to time wives of the Tsar’s chanters and krestovye diaki were given 5 arshins each of bagrets for opashen’, 10 arshins of damask for letnik, more rarely — taffeta for “holiday telogreya” (quilted jacket, similar to fur coat) or a fur coat; daughters were given, as a rule, bagrets for opashni, sometimes instead of their father’s annual payment with cloth [23, № 88, fol. 90; № 94, fol. 43; № 281, fol. 345; № 284, fol. 164; № 292, fol. 56; № 296, fol. 193, 253; № 300, fol. 78—79; etc.].

The specified articles of woman’s clothing demonstrate how the female part of families of the Russian singers of the late Middle Ages dressed like. The picture is supplemented by the description of the Tsaritsa’s choir diak Leonty Sushinsky’ s wife costume (the 1690-s). When going on a visit with her husband, the diak’s wife put on treukh (fur cap with two ear flaps and a back flap), “threaded (with pearls), with sable fur”, in the value of 15 roubles; kokoshink (woman’s headdress in old Russia) “gilded, with pearls”, in the value of 7 roubles; a shawl, “embroidered in gold”, in the value of 1 rouble [4, p. 157]. By the way, the annual monetary salary of Sushinsky was equal to 20 roubles at that time.

The documents describe the clothes of the Tsar’s singers in particular (often with the indication of the cost and fabrics used for sewing and measurements). In whole the variety of garments was determined by: designation — casual, hodil’noe (everyday), prihozhee

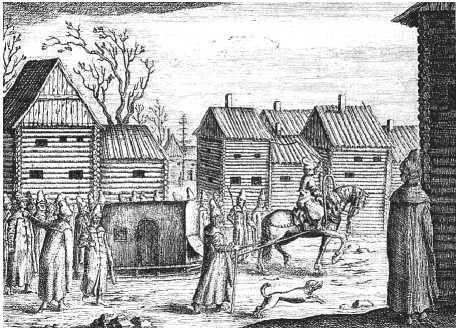

Clothing of wealthy residents of Muscovy. 17 th century engraving [13, p. 175]

(to be worn when on duty), holiday, “proezhee” (for traveling), service, as well as outwear and underwear; the time of year — warm, cold; the place of a singer in the choir.

In the early 17th century young diaki were usually given odnoryadkas (more rarely kaftans), which were made of many-coloured English cloth or lundysh [another type of English cloth] with laces of black silk with “semi-silver” tassels (or silver buttons). Trimming was made of velvet. The garments were supplemented with a semi-gilded girdle, a hat with fox fur [23, № 203, fol. 115—119; № 204, fol. 504—505]. Singers of the main stanitsas wore more modest odnoryadkas as everyday home clothes. In the court they appeared in “prihodnye” (for service) kaftans: in the second half of the century each of them was supplemented by 2 outwear and 2 underwear kaftans. An outer kaftan was made of English сloth or “stamed” (light woolen cloth) “with hare lining”, with beaver fur trimming and “silk buttons”; the second kaftan was made of “carmazin” cloth “with squirrel lining”, with scarlet taffeta trimming or “what fitted well”, with silk “laces” and silver buttons. The first of the underwear kaftans was made of taffeta or obyar’ (thick silk fabric) with lining of kindiak and taffeta trimming, it was edged with gilded or silver lace; the second kaftan was made of kindiak with lining of krashenina (homespun coarse cloth), with kindiak trimming and buttons wrapped in silk “on a silver lace”. Those everyday kaftans were supplemented with a hat with a crown made of red cloth and trimmed with sable fur [22, № 24211, fol. 1; №24788, fol. 1; № 24803, fol. 1; № 25067, fol. 1; 23, № 384, fol. 65, 123—124] 1. Holiday kaftan was made of ‘stamed’ or “carmazin” cloth with arctic fox fur underneath, beaver fur trimming and gilded silver buttons. Sometimes it was edged with a silk lace. “Dark red” or scarlet trousers, a velvet hat with sable fur and mittens with beaver fur were given to the holiday kaftan [22, № 24363, fol. 1; № 24761, fol. 1; № 24809, fol. 1; etc.]. In September 1679 the senior choir singer Pavel Afanasiev was given a sash «just like the one “ryndas” (Tsar’s bodyguards) wear»; later such sashes were given to ordinary singers as well [22, № 18497, fol. 9]. During the trips the singers wore dolomans and emurluks; in winter they were given warm kaftans, fur coats, zipuns and mittens [22, № 3369, fol. 1—2; № 18497, fol. 9; № 24594, fol. 1; № 24626, fol. 1; 23, № 384, fol. 51; etc.]. Singers, who had no salary, received money for blouses, “trousers” and boots [23, № 1076, fol. 269; etc.].

It should be specifically emphasized that clothes of the singers of the patriarchal choir almost did not differ from the clothes of the Tsar’s singers. Maybe they were slightly more modest. A kindiak kaftan, for example, was trimmed with krashenina, a lining of sackcloth, buttons “on a lace” (“with silk laces”). The patriarchal singing diaki also wore odnoryadkas with gilded silver buttons, semi-kaftans, “proezhie warm kaftan”, dolo-mans, fur coats, woolen cloth or velvet hats with sable or marten fur, etc.; from time to time they were also given money for boots [19, № 38, fol. 150, 165, 549 etc.; № 73, fol. 234, 268, 361; etc.; 20, № 20, fol. 138—139, 145, 189; № 43, fol. 96, 124, 129 etc.).

It is common knowledge that in the medieval society with its developed system of symbols, corporate belonging of a person was expressed through clothes as well, which was changed in case of transition into another social position. The garment descriptions of the main choirs’ singers in Old Russia, available in documents, depict typical clothes of town residents — service class people.

Despite the fact that the service of singers brought their families all necessary things for support of a certain standard of living, quite often there were situations, when diaki and podiaki had to ask the authorities for help and incur debts. In 1654—55 eleven Tsar’s chanters and four krestovye diaki were given 30 roubles each “as an aid” [22, № 5496, fol. 1]. In April and November 1661 as well as in January and June 1663 all singers of the patriarchal choir “due to the rise in prices for bread and other products” which came as a result of the fall in exchange of copper coins (which resulted in “copper riot”), were given financial aid in the value of half of the salary and more; in January 1664 “due to their poverty” the singers were given 2,5 roubles each with silver [19, № 51, fol. 145—148, 472; № 54, fol. 117—119, 124, 353]. But, perhaps, the most terrible disaster for a family was fire. In August 1664 the diak of the Tsar’s choir Kozma Rodionov was given 5 roubles “in connection with the fire destruction”; in September 1668 diakivictims of a fire from the same choir Nikita Kazanets and Feodor Prokofiev were given 20 and 10 roubles “for the yard building” [27, v. 23, p. 524, 1104]. In 1675 the misfortune overtook the Tsar’s chanter Evdokim Evstratov, who became a victim of a fire and lost all his property. In his petition to the Tsar he also wrote, that “the cellar is also burnt down and collapsed, and everything was taken away, and now I, holop of yours, live on the wasteland, and suffer from rain and snow and frost, and, my Tsar, I have no money to rebuild my home”. Therefore he asked to give him money instead of the annual amount of cloth, which was due to him for three years [25, fol. 75—76]. Families of the patriarchal singers, who had suffered from “fire destruction” in the same year, were given flour and cereals [20, № 29, fol. 306, 307, 365]. The fire, which wrapped Kitai-gorod and Bely gorod (districts of Moscow) on July, 26, 1699

caused damage to almost all chanters of the patriarchal choir. In this connection by decree of the patriarch the diaki were given 1 rouble each, podiaki — 50 copecks each, and diak Gavrila Rodionov and podiak Peotr Nikitin, who had lost everything, 10 roubles each [19, № 173, fol. 297—299]. But singers and their families needed help and assistance not only because of fires. In March 1674 the Tsar’s singing diak Vladimir Golutvin asked to give him cloth for odnoryadka, as he was “robbed by thieves” [27, v. 23, p. 724].

Sometimes singers of both choirs resorted to loans. After the death of the Tsar’s choir diak Kozma Rodionov it was ordered to question his mother Tatiana on August, 18, 1669 if there was any “outstanding debt” of her son. According to Tatiana, her son “lent” money “for various home needs after the fire” and did not have enough time to pay off 26 roubles. The Tsar ordered to discharge the debt [27, v. 23, p. 73—74]. The Tsar’s singers often lent money in such significant amounts that could not repay them. In December 1669 in Tainy Prikaz Aleksey Nikiforov was given 60 roubles “to pay the debts”; in February 1670, the same prikaz paid 200 roubles of “bondage debt” for Osip Golchin to Chudov monastery [27, v. 23, p. 1248, 1268]. The patriarchal singing diaki and podiaki were given money on “loan bonds”, as a rule, in the patriarchal Treasury Kazenny Prikaz. The amounts did not exceed 2—3 salaries and were paid annually from their salary [19, № 64, fol. 298—300; № 67, fol. 387; № 69, fol. 267].

The richest singing diaki lent money (or goods) on security, not always making profit of it. In 1665 Pavel Ostafiev had litigation with gardener M. Shaposhnikov, who had lent 50 roubles from him with a liability to cede his yard with all its buildings in case of nonpayment; by the Tsar’s decree after the sale of the yard the singer was given back only 40 roubles. The singing diak Aleksey Davydov, who lent 65 roubles to a widow from Kadashevskaya sloboda on security of her yard, in 1689 tried to return his money, but failed: it turned out, that the widow had previously pledged her yard to some foreigner for 63 roubles. At the lawsuit of the senior choir singer Fedot Ukhtomsky in 1698 a resident of Kadashevskaya sloboda, who had previously lent from him goods in the value of 108 roubles and barley to the amount of 50 roubles, became his slave for 11 years and 2 weeks; in the same year Denis Kondratov filed a complaint against his brother-in-law, a podiak of Bolshaya Kazna (Prikaz of Big Treasury), who had lent 5,5 roubles from his wife and did not want to give the money back [9, p. 216—217].

Dwelling upon the everyday life of the Russian medieval professional musicians, one cannot but mention their homes as well. The singers’ yards were situated in different districts of Moscow, and in most part — not far away from the Kremlin. In Kitai gorod they lived in Vvedenskaya Mostovaya and Spasskaya streets, near the Moskvoretskie gates and the Varvarskie gates, near Muchnoy Ryad behind the Neglinnenskie gates, near the churches of Saviour of Smolensk and Nikola Mokry, etc. In Bely Gorod — in Znamenskaya, Nikitinskaya, Novaya, Bolshaya Mostovaya, Tverskaya streets, in old Vagankov, in Aptekarsky alley and alley of the church of Dionisyus, near the churches of Dmitry Solunsky in Arbat street, the church of the Intercession, the church of Nikola behind the Kamenny bridge, of St. Savva Stratilat and other. Some singers lived in Zemlyanoy Gorod (behind the Smolenskie gates in Povarskaya street) and in Zamoskvorechye (Ordynskaya street), and also in Moscow settlements or near them (Konyushaya, Ikonnaya, Barashskaya, Semenovskaya, Bronnaya, Novomeschanskaya, Patriarshaya). In the second half of the 17th century there was a localisation in the settling of the patriarchal singers, who established their own “slobodka” (small settlement), whereas the Tsar’s singers were still settling down in different districts of the capital.

Usually for the diaki of the Tsar’s choir the public yards were intended, which were under the supervision of Tainy, or less often, of Kazenny prikaz. There were several ways to acquire those yards. First of all, they could be bought from serving people, including the former singers and krestovye diaki, if they had been built at their expense. For example, in 1656 in Aptekarsky alley a yard for Danila Lazarev was acquired from a former krestovy diak for 70 roubles, and from a stoker of Aptekarskiy prikaz — a yard for Luka Alekseev; in 1657 Tikhon Artemiev owned a yard by the church of Nikola Mokry, which was bought by the Treasury for 110 roubles; in 1664 a yard was acquired for Efim Feofanov behind the Nikitinskie gates, on Kozye swamp, by the church of Spyridon the Miracle-Worker; in the 1670-s the treasury bought “a yard structure” by the Moskvoretskie gates for Nikita Kazanets “from his brother”, a Tsar’s dining room stoker for 180 roubles, for Feodor Prokofiev from a translator of Tainy prikaz for 200 roubles, the yard of the former Tsar’s chanter Petr Matveev for 110 roubles, etc. [22, № 17440, fol. 8, 9; 25, fol. 85, 90—91; 27, v. 23, p. 252].

Moscow streets and yards. 17th century engraving [13, p. 212]

Sometimes the treasury money for construction or acquisition of yards was given to singers. In 1665 Nikita Nesterov was given 200 roubles in Tainy prikaz “for the construction of the yard”, and Kozma Rodionov — 60 roubles; Savva Krutitsky, who built his yard in 1678 in Znamenskaya street, was given 15 roubles; in October 1691 Ivan Grigoriev was given 50 roubles for the acquisition of a yard of Master prikaz [22, № 17440, fol. 4; 25, fol. 101; 27, v. 23, p. 595, 683]. And finally, when necessary, Tainy prikaz at its own expense built houses for the Tsar’s singers. Thus, in 1674 between Smolenskaya and Nikitinskaya streets, on the former yard of sokolnik (court hunter) I. Stukolov the yards for five diaki were built; wooden logs and “iron supplies” for the construction of the yards for the ten newly accepted diaki from Novgorod were bought in November 1675 [22, № 17440, fol. 3; 27, v. 23, p. 1387).

As far as in most cases the Tsar’s singers and their families lived in yards, which had been acquired or built at the expense of the treasury, the yards were came into their possession conditionally. After retirement from the choir this or that chanter forfeited the right to that lodging. In 1657 a yard behind the Neglinnenskie gates near Muchnoy Ryad, which had previously belonged to Ivan Konyukhovsky, was handed over to Elisey Gavrilov. But soon the yard of a retired person Vasily Aristov in Tverskaya street near Zhitny Ryad caught Elisey’s fancy, and by January 1659 he acquired the right to own that yard [22, № 17440, fol. 8; № 6310, fol. 1—2]. In the 1660—70-s Danila Lazarev’s yard, acquired by the Treasury, was passed on to Prokofy Nikitin; the yard of Nikita Larionov by the church of Nikola Mokry — to Fedor Rostovets, whose town residence behind the Borovitsky bridge by Liebyazhy yard was given to Ivan Lvov by Tainy Prikaz; Kozma Rodioniv’s yard, for which two thirds of the cost was paid by the Treasury, was given to Dmitry Rostovets, while Kozma’s mother got 31,8 roubles; in the big yard of the former krestovy diak Feodor Koverin three young singing diaki were settled [22, № 17440, fol. 2, 9—11; 25, fol. 90; 27, v. 23, p. 1328]. Yards of other serving people were also given to singers. For example, in the 1660-s one of the yards of okolnichy I.B. Khitrovo was taken for Ivan Agafonov “at the expense of the Tsar”, and only after the singer’s death the yard was given back to its previous owner [24, v. 21, p. 282—283]. In 1677 Vladimir Golutvinets was given a yard of the former court church ecclesiarch in Znamenskaya street [22, № 17440, fol. 4].

Some singers of the Tsar’s choir built or acquired yards at their own expense. Thus, Samoilo Ivanov and Denis Perfiriev in the 1670-s jointly owned a yard, but after its destruction in fire they built separate lodgings at their expenses [22, № 17440, fol. 3; 27, v. 21, p. 378]. In a similar way Feodor Rostovets built a lodging after a fire; and Dmitry Tveritin acquired a ready-made yard for 76 roubles from a podiak of Chelobitny Prikaz behind the Prechistenskie gates by the church of St. Prophet Elijah [22, № 17440, fol. 6, 10]. The Tsar’s singers also lived in yards, which had come to their possession from their relatives. In the 1650-s Peotr Pokrovets lived in the yard of the deceased grandfather of his wife by the Vsesviatskie gates in Nikitinskaya street, but on a taxed land [22, № 17440, fol. 7; 25, fol. 91]. In 1678 Artemy Romanov acquired a yard by Moiseevskie hospices between Tverskaya and Nikitinskaya streets, which had been bought by his father for 70 roubles from a priest [22, № 17440, fol. 6].

As far as the yards of the patriarchal choir’s singers are concerned, they were acquired in different ways. In the first half of the 17th century they could be found in various districts of Moscow [26, p.108, 110, 152 etc.], but then in documents there appears a reference to a special patriarchal “Singers’ small settlement” (“Singer’s street”) in Kitai Gorod behind Vetoshny Ryad. For example, in July 1671 “working people” and carpenters were paid for digging a well here and made a framework for it; in November 1676 a singing diak Evstafy Pavlov also hired people to dig a well and carpenters, who after a fire cleaned out the old “burnt” well, made a framework and paved the ground around it [19, № 73, fol. 322—323; № 89, fol. 332]. At that time the patriarchal singers, who lived outside the Singers’ settlement, were settling down there. Thus, in November 1677 podiak Ivan Ushakov was given 1 rouble “to move his belongings from his house” [19, № 92, fol. 318]. The settlement was growing bigger. By the decree of the patriarch in September 1688 “a yard place in Kitai Gorod, adjacent to Vetoshny Ryad and the town residence of the metropolitan of Novgorod and to the yards of the most holy patriarch’s singing diaki and podiaki” was acquired from royal carver B.A. Golitsyn for 1000 roubles for the construction of yards for his “home” singers. And soon, on November, 22, another decree was published. That decree ordered to build in the singers’ residential area “the stone palaty (chambers) with inner porches and basements, and every yard must have stone gates with arches, and everything must be done according to the drawing” — all in all 33 yards. It was ordered to buy various supplies and hire people. Masons were paid for the construction of each “palata” 35 and 20 roubles, which points at different sizes of the houses [19, № 129, fol. 315, 379—95]. In January 1690 the patriarch went to see the finished buildings “to distribute those palaty among the chanters and podiaki, to define a lodging for them” [19, № 134, fol. 165]. Throughout the 1690-s the singers were occasionally given money to finish building “the stone palaty” with doors, benches, floors, ovens, etc.; money was also given for the construction of “the rest” yards [19, № 134; fol. 239—240, 246; № 137, fol. 317, 333, 386; etc.]. According to the 1695 inventory of Kitai Gorod in Pevcheskaya street there were yards of almost all of the singers of the patriarchal choir, a few yards of the Tsar’s krestovye and singing diaki, some citizens [8, p. 9—10, 18—19]. “The chambers” of the latter were being gradually bought out by the patriarch. In December 1699 he ordered to acquire “a yard and a chamber building” on his land, which belonged to a sexton of the church of Twelve Apostles, for his podiaki or other serving people to live from that day on in those “chambers” [19, № 173, fol. 316]. Separate yards of the patriarchal singers were situated in Bely Gorod as well [19, № 137, fol. 297].

It should be mentioned that for singers of both main Russian choirs the choice of land where their lodgings were situated was of great importance. As a rule, the singers’ yards were exempted from taxes (“whitewashed”); sometimes it was stipulated that they were “on the white land” or “on white spots”. In the 1638 description of Moscow such indications are made in relation to the yard “in Old Vagankov” of krestovy diak Ivan Semionov and to the yards of podiak Kuzma Andreev and the patriarchal singing diak Grigory Potapov near Barashskaya sloboda and surrounded by the yards of taxed tradespeople [26, p. 32, 227]. However, some singers due to this or that reason owned yards on taxed lands, and for a long period paid duties to the Treasury. Sometimes lodgings were situated on the church lands, but the clergymen sought their removal displacement. In May 1629 the Tsar ordered the Tsaritsa’s krestovye diaki to transfer land for yards wherever they could find it [1, p. 103]. In October 1655 podiak Fedor Trofimov was given 2 roubles from the patriarch’s treasury for “the yard displacement ” from the land of the Cathedral of the Annunciation “to the land of duke Yury” [19, № 38, fol. 548]. In rare instances the singers lived in monastery town residences. The Tsaritsa’s krestovy diak (then the Tsar’s singer) Grigory Korsakov, for example, in the beginning of the 1680-s lived in the town residence of the St. Simon monastery in the Kremlin and the monastery was paid 6 roubles annually from the Treasury for his “housing” [6, v. 11, p. 57].

The sizes of the singers’ yards were different, and quite often they were growing bigger as they became more remote from the centre or depended on the social position of the yard owners. In the first half of the 17th century the yard of the patriarchal choir diak Neustroy Sharapov near the cemetery by the Varvarskie gates, was almost 10 sazhens (1 sazhen = 2,13 meters) long, 5 sazhens wide; the yard of Ivan Danilov, a diak of the same choir, situated in Kitai Gorod — 5,5 long and 3 sazhens wide; podiak Boris Ivanov’ yard by the church of the Resurrection in Uspensky ravine — about 14 sazhens wide and more than 15 sazhens long, etc. [12, v. 2, p. 28, 32, 74 etc].

Residential yard. Residential yard.

17 th century miniature

The “yard buildings” were also different. In the 1670-s the Tsar’s singing diak Ivan Novgorodets owned a yard behind the Smolenskie gates in Povarskaya street. There was a stone palata, bars on three windows, “iron doors”; before the palata — an inner porch, underneath — a basement; ground-floor buildings; a house with a porch; a stable with 4 stalls in it, above it — a drier; a well “with a framework”; an orchard with 24 apple trees, 2 pear-trees and redcurrant bushes — the length of the yard was 19 sazhens, width — 18 sazhens; a fence with 19 bays [27, v. 21, p. 205]. In the yard of krestovy diak Luka Alekseev who died in 1684 there was a chamber on a wooden log foundation, in the upper inner porch — “a closet”, above the inner porch — an attic, two cellars, “a barn”, a cellar “for utensils”, etc. [22, № 21198, fol. 3].

As we can see, while Russian professional singers were serving their families were provided with everything necessary. That is why the loss of working places or death of singers for many families resulted in significant changes in their material status.

The reasons for singers’ dismissal were usually a loss of voice, advanced age or some offence. Sometimes former singers, whose families’ welfare fully depended on their salary, applied to their previous working place for help. Some of them succeeded in getting a place in the new quality. At the end of the 1650-s a retired podiak Savva Semenov became a teacher of young podiaki. A former podiak Aleksandr Isakov, who had learned to write books from the Chudov monastery’s elder Evfimy, in 1693 was taken on as a book scribe. A salary was fixed for both of them [19, № 47, fol. 21, 319; № 147, fol. 111]. Quite often retired singers of the central Russian choirs were sent to the local bishops’ choirs. In March 1658 Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich ordered to send his singing diak Venedikt Grach “from Moscow to live in Smolensk with his wife and children”, where he was to become a singer of the archbishop of Smolensk [30, p. 10]. By the order of the same Tsar in September 1659 Vasily Aristov, Semen Sidorov and Afanasy Suzdalets with their families were sent to Astrakhan to the choir of the archbishop of Astrakhan and Tersk [6, v. 4, p. 250]. The diaki, who had been accepted to the Tsar’s or the patriarchal choirs from remote towns, after their retirement could return there at their will. For example, in 1682 it happened to Mikhail Konstantinov, Matvey Kulikovsky, Ilya Grabovsky and others, who were “dismissed” and were let go “from Moscow” [23, № 124, fol. 30, 31].

Many families of singers found themselves in a particularly difficult situation after the death of their providers. Singers often died young, while being in the staff of choirs. They also suffered from epidemics together with other residents of the capital. During the terrible plague epidemic of the summer-autumn 1654, when the most part of the Moscow population died out, many singers died (Ivan Konyukhovsky, Bogdan Zlatoustovsky, Kondraty Andreev, Grigory Panfilov and others) [6, v. 3, p. 509]. The patriarchal choir then was reduced in half; among the deceased in the September staff list there were singing diak Yakov Makarov, po-diakons Nefed Grigoriev and Timofey Eremeev, podiaki Grigory Potapov, Kozma Tveritin, Mikhail Vasiliev, Stepan Ulyanov and others [19, № 38, fol. 8—14].

A widow of a Tsar’s singer or krestovy diak “with little children” was usually given those salaries, which the deceased person had not been given while alive. In 1636 the widows of Kanon Fedorov and Vasily Nikitin were given 5 arshins of cloth, which their husbands had earned at consecration of the new court church; in 1640 the annual amount of cloth in the value of 5 roubles was given to Tatiana, Dmitry Markelov’s widow; in January 1679 krestovy diak’s widow Fekla was given 17,2 roubles instead of the annual and Communion cloth for 2 years; Nikolay Sobolevsky’s widow Aksinya in June 1688 was given 15 roubles of her husband’s monetary salary and cloth in the value of 3 roubles “for her not to die of starvation and not to come to ruin”; etc. [22, № 2992, fol. 5—6; № 18430, fol. 1—10; 23, № 292, fol. 1, 8; etc.; 25, fol. 6]. Up to 10 roubles were also added “for the funeral”. Some families, who, probably, had just arrived from a remote town and had no time to earn money, occasionally received aid after the death of the provider. Thus, in February 1674 Maksim Sibirets’s widow Akulina “with children” was given 5 quarters of rye and oats from the Tsar’s “stone granaries”, then 10 roubles, and in 1676 every month she was given “every day food” [27, v. 21, p. 220, 1703; v. 23, p. 250]. As a rule, widows of the patriarchal diaki and podiaki were given 1—2 roubles for their husbands’ funeral and some part of the husband’s annual salary, which he had not been given [19, № 67, fol. 379; № 73, fol. 275; № 75, fol. 12; № 81, fol. 276; № 99, fol. 265; etc.; 20, № 29, fol. 450]. Families in the most disastrous situation were given 0,5—1,0 roubles “of charity” from the treasury “because of their poverty” [19, № 134, fol. 238; № 147, fol. 314; № 152, fol. 253; № 173, fol. 300; etc.]. In rare cases they were rendered a longterm aid. For example, in October 1674 the patriarch ordered to give singing diak Dmitry Yaroslavets’s widow 6 quarters of rye and oats a year from his granaries “until she gets married”; in 1676—1680 podiak Ivan Mikhailov’s widow Aksiniya with children was given a half of her husband’s salary [19, № 89, fol. 84; № 92, fol. 19; № 93, fol. 83; 20, № 29, fol. 265, 418].

Thus, the documents let us reconstruct in detail the everyday life of musicians and their families of the medieval Russia (especially for the 17th century). Dwelling upon the singers’ morality is a much more difficult task: the sources tend not to mention the obvious positive aspect of singers’ actions but reveal those negative deeds, which were leading to investigations or even court trials. The dominating morals, which now may seem coarse to us, were also quite typical of the Middle Ages.

Describing everyday life of the Tsar’s and the patriarchal singers, we have touched upon some aspects, which depict the morals of the environment under consideration (taking care of immediate relatives, the will to educate sons, etc.). Particular observations in that relation can be extracted from references in the sources to everyday customs and traditions.

Having access to the chambers of the church’s head, the Tsar’s and the patriarchal choirs’ singers on important, from their point of view, moments of their lives tried to receive the blessing of the patriarch. For example, after the wedding the newlywed singer visited the patriarch “with wedding vegetables” or “with the wedding honey cake”, and the patriarch blessed him, as a rule, with the icon of the Mother of God in a framework [12, v. 1, p. 1008, 1017, 1020 etc.; 19, № 85, fol. 15; № 93, fol. 89, 100; etc.]. The same was done by singers on their name days. In 1657—58 Ivan Kazanets, Grigory Kirikov, Ivan Shusherin and others visited the patriarch “with the name-day cake”. Apart from the blessing, the latter gave each of them 0,5 roubles; but in the following years people celebrating their name day, just like the newlyweds, were blessed by the icons of the Mother of God “on paint” or “on gold” [19, № 41, fol. 257; № 43, fol. 229, 236; № 70, fol. 3, 4; etc.; 20, № 20, fol. 4, 15; etc.].

Sometimes in connection with a disease some singers made an oath to visit this or that monastery, and the authorities did not put obstacles in their way. In July 1682 the Tsar’s singing diak Andrey Novgorodets was permitted to go to the Tikhvinsky monastery in Novgorod “for he vowed to pray”. Voyvodes in Tver,

Torzhok and Novgorod were ordered to give him 3 carriages (out and return), 5 escorts and to let him pass “without detention” [18, № 2412, fol. 1—2]. In February 1692 the Tsar’s singer Kuzma Grigoriev, who had given an oath to visit a monastery in the Ukraine “due to his disease”, asked, in order not “to anger God”, to give him his salary and money for the road. Having received the money, “the traveling permission” and carriages, he made a pilgrimage [18, № 4364, fol. 1].

The dominating morality brightly manifested itself during home parties. In the late 1650-s “about ten people or more” came to visit the Tsar’s singing diak Danila Lazarev, among the guests there was a sotnik (a military rank in Russian Strelets Troops) and two court hunters. The guests came from the court stoker with some girl called Anyutka. During the interrogation Anyutka told that she had seen the court hunters before at Acsyutka’s, that for some time she had lived at a singer’s, whose place was visited twice by serving people Grigory Yushkov and Ignaty Uvarov, that later she left to live in the yard of the latter [18, № 4891, fol. 1]. Among other things in this story the singing diak’s circle of contacts (guests) is noteworthy. When seeing each other out of service, the singers sometimes thought of quite noble deeds. In 1682 Luka Andreev, while staying at Ivan Vlasov’s place in Novomeschanskaya sloboda, said, that in St. Simon’s monastery the archimandrite wanted to make monks of two singers, and “the latter did not want to”. Both the Tsar’s singing diaki decided to “take away” their Ukrainian colleagues and shelter them in the yard of Ivan Vlasov, and they did that [6, v. 10, p. 206].

Not always staying on a visit ended well. Thus when the Tsar’s choir diak Leonty Sushinsky with his wife was visiting I. F. Volosheninov, a famous teacher of “comedy art”, in Meschanskaya sloboda a fight with mutual insulting burst out between the friends. At the “interrogation” Sushinsky’s wife blamed Volosheni-nov’s wife for “starting to abuse and dishonour her, for beating, mutilating and robbing her”, and tearing away of her headgears (treukh, kokoshnik and the flaw). As for Volosheninov’s wife, she said that the singer with his wife came in late, stayed for long and “began to beat and mutilate her in her own house, and that her husband on that day was forced to run, and that Leonty broke all the windows in her house, and took away the Polish cherry leather jacket” [4, p. 157].

Generally, singers and members of their families were quite often involved in quarrels and fights that were considered common events in the life of medieval community. Here are some examples.

As a result of a quarrel between two podiaki in 1639 Boris Davydov, who had “broken” Ivan Gavri-ilov’s arm, paid half of the salary — 2 roubles — to his colleague “for treatment”; in September 1698 the patriarch ordered to deduct 10 roubles from podiak Ivan Ivanov’s salary in favour of Grigory Andreev for “Ivan had beaten and mutilated him, Grigory” [19, № 12, fol. 9, 11 etc.; № 173, fol. 14]. In July 1684 Moscow “tradeswoman” Maria Fedorova said in her petition to the Tsar, that the Tsar’s singing diak Pavel Alekseev “had bothered” her and her son and had accused them of “abusing and dishonouring and beating his wife” and “dishonouring” him, by which he wanted to “bring her losses for nothing”; she asked to interrogate the singer and ask whether he was present at the fight between the women and whether he could call any witnesses’ names [18, № 2954, fol. 1]. We know that for dishonouring of a singer one had to pay a heavy fine in the singer’s favour. Probably, Pavel Alekseev decided to take the chance. It took several years to consider the case of bourgeois Foma Mikhailov’s claim against the Tsar’s choir diak Yakov Borzakovsky, who mutilated Mikhailov’s daughter Uliyana [18, № 2995, fol. 175—192]. In May 1691 singing diak Ivan Polyakov was called to Sysknoy prikaz [responsible for searching of fugitives] to be “interrogated on murder” of a K. Oborin [25, fol. 101].

Documents mention many other offences connected with the singers of the main Russian choirs. Here we can find liability breach, unsettled debts and even sometimes thefts. In the spring of 1659 the Tsar’s chanter Danila Kazanets filed a petition, saying that singing diak Kozma Ermolaev “had taken with him” his underwear dress and he had nothing to “wear under his odnoryadka” [22, № 6384, fol. 1]. In 1689 ther was a trial “about two finger rings” between gardener Y. Patokin and the above-mentioned tradeswoman Maria Fedorova. One finger ring was given to Patokin, and the second one appeared to be in possession of “the Greek” Ivan Andreev, who lived in Tsar’s singer Larion Komov’s “house”. In case of further investigation the singer made a written promise “to bring” the Greek to Posolsky (Ambassador) prikaz, but failed to do that, therefore the gardener asked to recover 20 roubles from him [18, № 3965, fol. 1]. In April 1695 “a foreign tradesman from Holland” filed a petition, saying that in September 1694 the Tsar’s singing diak Grigory Korsakov had borrowed 10 roubles from him till Christmas, and wrote a “warrant”, but did not give the money back. An order was issued “to find and interrogate him” [18, № 4602, fol. 1].

The morality of singers and their family members were getting revealed during family relationships crises. Thus, on March, 8, 1697 the singing diak Ivan Podvin-sky’s wife in the presence of witnesses gave a “note” to her husband, that “after talking” to him “in amicable way”, she asked him to ask the patriarch humbly for divorce, and as the patriarch would tell, either “to admit monastiс vows” or “live in freeness”. She also said, that she had taken 200 roubles from her husband for taking the veil and “for subsistence” and her dress, therefore from that moment on she had nothing to do with the singer and “his yard and his belongings” [21, № 17055, fol. 1]. Quite often a divorce for a woman ended in going to the convent, while her ex-husband had the right to remarry. A third marriage was considered as a serious delinquency. For example, the patriarchal singing diak Vasily Moiseev by March 1680 had been retired from the choir for that [19, № 99, fol. 12].

Dismissal was not the only punishment for singers’ delinquencies; they were also “exiled” to subordination in remote monasteries. In 1661—62 a diak of the patriarchal choir Nester Ivanov for “a shabby act” was exiled to the Kirillo-Belozersky monastery, and his garments and “other household stuff” was kept in the Patriarchal prikaz (but when the diak was back in one year, all his belongings “had rotten down”) [22, № 8455, fol. 5]. In the Spaso-Prilutsky monastery in 1668 from time to time 3 altyns were given to “the Moscow singer, the one exiled” [24, №7528, fol. 74]. In August 1697 the Tsar’s choir diaki Nikita Ryazantsev and Spiridon Ivanov returned after confinement in monastery [9, p. 219].

Though it occurred more rarely, the Moscow singers were involved in political cases. In January—February 1525 as a result of the investigation concerning Maximus the Greek, also known as Maksim Grek and boyar’s son I. N. Bersen Beklemishev, who were condemning the grand duke’s ruling methods, Fedor Zhareny, krestovy diak of the All-Russian metropolitan was put on trial for delivering “evil” speeches “as if he was mad”; upon decision of the duke, the metropolitan and the whole Cathedral, he was punished with “torgovaya kazn’ (a kind of punishment) — he was beaten with whip and his tongue was cut off” [2, p. 143—145; 16, p. 222].

Podiak Fedor Trofimov, the author of philippic orations about patriarch Nikon and church reforms being carried out by him, in January 1661 was exiled to Toboslk with his wife and children. His life ended when he “was committed to the flames for impertinent speeches against the Tsar” [3, p. 103—104 etc.; 5, p. 86—87]. Evidently, the Tsaritsa’s krestovye diaki Michael and Martyn Protopopovs were exiled in March 1666 to monasteries with an order “to be present at the church singing and to carry out all kinds of work and to be kept under heavy supervision” for being supporters of “the schism” [7, p. 409]. After the conviction of retired patriarch Nikon the Tsar ordered the head of the Streltsy to keep Ivan Shusherin under guard for being “Nikon’s podiak”. After 3 years of imprisonment, Shusherin “had gone through lots of evil” and was sent back to Veliky Novgorod, where he was born [27, v. 21, p. 1363; 32, p. 61]. In September—October 1689 after the investigation concerning the case of Tsarevna Sofya and streletski conspiracy her krestovy diak Anton Muromtsev was sentenced to exile [29, p. 89].

Thus, the examined records allow us to conclude that the Tsar’s and the patriarchal chanters’ everyday life and moral customs were not much different from the Russian serving class people’ life of the 16th—17th centuries. These documents provide additional features to the social portrait of the medieval Russian professional musicians.

Список литературы The central choirs singers’ social status, everyday life and moral customs in the Russian state of 16th-17th centuries

- Acty istoricheskie, sobrannye i izdannye Arkhe-ograficheskoy Komissiey [Historical Acts collected and published by the Archaeographical commission], v. 3. St. Petersburg, 1841.

- Acty, sobranii v bibliotecakh i arkhivakh Rossiyskoy imperii Arkheograficheskoy Expeditsiey Imperatorskoy Academii Nauk [Historical Acts Collected by the Archaeo-graphical Expedition of the Academy of Sciences in the Libraries and Archives of the Russian Empire], v. 1. St. Petersburg, 1836.

- Belokurov S. A. Yuriy Krizhanich v Rossii [Yuri Krizhanich in Russia]. Moscow, 1902.

- Bogoyavlensky S. K. Moskovskaya Meshchanskaya sloboda v XVII v. [Moscow Meshchanskaya Sloboda in the 17th century]. Nauchnoye naslediye [Scientific heritage]. Moscow, 1980.

- Breshchinsky D. N. Zhitie Korniliya Vygovskogo [The Life of Cornelius Vygovsky]. Drevnerusskaya knizhnost' [Old Russian book]. Leningrad, 1985, pp. 86—87.

- Dopolneniya k actam istoricheskim, sobrannie i izdan-nie Arkheograficheskoy Komissiey Imperatorskoy Academii Nauk [Additions to historical acts collected and published by the Archaeographical commission.], v. 1. St. Petersburg, 1846; v. 3. St. Petersburg, 1848; v. 4. St. Petersburg, 1851; v. 10. St. Petersburg, 1867; v. 11. St. Petersburg, 1869.

- Zabelin I. E. Domashniy byt russkogo naroda v XVI—XVII vv. [Household life of the Russian people in the 16th—17th centuries], v. 2. Moscow, 1901.

- Zertsalov A. N. Moskovskiy Kitay-gorod v XVII v. [Moscow China Town in the 17th century]. Chteniya v Ob-shchestve istorii i drevnostey rossiyskikh [Readings in the Society of Russian History and Antiquities], book 2. Moscow, 1893.

- Izvekov N. D. Moskovskie kremlevskie dvortsovye tserkvi i sluzhashchie pri nikh litsa v XVII v. [Moscow Kremlin palace churches and persons who serve them in the 17th century.]. Moscow, 1906.

- Leont'yev A. K. Nravy i obychai [Morals and customs]. Ocherki russkoy kul'tury XVI v. [Sketches of Russian culture of the 16th century], book 2. Moscow, 1877, pp. 33—75.

- Leont'yev A. K. Byt i nravy [Life and manners]. Ocherki russkoy kul 'tury XVII v. [Sketches of Russian culture of the 17th century], book 2. Moscow, 1879, pp. 5—29.

- Materialy dlya istorii, arkheologii i statistiki goroda Moscvy, sobrannie i izdannie rukovodstvom Ivana Zabelina [Materials for the history, archaeology and statistics of Moscow, collected and published by I. Zabelin.], v. 1. Moscow, 1884; v. 2. Moscow, 1891.

- Oleariy A. Opisanie puteshestviya v Moskoviyu i cherez Moskoviyu v Persiyu i obratno [Description of a trip to Muscovy and through Muscovy to Persia and back]. St. Petersburg, 1906.

- Parfentjev N. P. The singers of the central choirs of the Russian state of 16th—17th centuries as the "sluzhi-lye lyudi" of the tsar's and the patriarch's courts. Vestnik Uzhno-Ural'skogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya: Sotsial'no-gumanitarnye nauki [Bulletin of the South Ural State Universiti. Series: Social Sciences and the Humanities], 2019, v. 19, № 3, pp. 94-104.

- Parfentjev N. P. Professionalnye muzykanty Ros-siyskogo gosudarstva XVI—XVII vekov. Gosudarevy pevchie diaki i patriarshie pevchie diaki i podiaki [Professional Russian musicians of the 16th—17th centuries. The Tsar's singing diaki and the patriarch's singing diaki and podiaki]. Chelyabinsk, 1991.

- Polnoe sobranie russkikh letopisey [The complete collection of Russian chronicles], v. 24. Petrograd, 1921.

- Razumovsky D.V. Gosudarevy pevchie djyaki i pa-triarshie pevchie djyaki i podjyaki [The Tsar's singing diaki and the patriarch's singing diaki and podiaki]. St. Petersburg, 1895.

- RGADA [Russian State Archives of Ancient Acts, Moscow]. F. 159. Inv. 2.

- RGADA. F. 235. Inv. 2.

- RGADA. F. 236. Inv. 1.

- RGADA. F. 236. Inv. 2.

- RGADA. F. 396. Inv. 1.

- RGADA. F. 396. Inv. 2.

- RGB. F. 178. № 7528.

- RGB. F. 380. № 6.3.

- Rospisnoy spisok Moskvy 1638 g. [List of Moscow 1638]. Publ. I. S. Belyaev. Moscow, 1911.

- Russkaya istoricheskaya biblioteca [State Public Historical Library of Russia], v. 21. St. Petersburg, 1907; v. 23. St. Petersburg, 1904.

- Sbornik vypisok iz arkhivnykh bumag o Petre Velikom [Collection of excerpts from archival papers on Peter the Great]. Publ. G.V. Esipov, v.1. Moscow, 1872.

- Ustryalov N. Istoriya tsarstvovaniya Petra Velikogo [History of the reign of Peter the Great], v. 2. St. Petersburg, 1858.

- Chteniya v imperatorskom Obshchestve istorii i drevnostey rossiyskikh pri Moskovskom universitete [Readings in the Imperial Society of Russian History and Antiquities at Moscow University], book 1, section 2. Moscow, 1902.

- Chteniya v imperatorskom Obshchestve istorii i drevnostey rossiyskikh pri Moskovskom universitete [Readings in the Imperial Society of Russian History and Antiquities at Moscow University], book 1, section 2. Moscow, 1908.

- Shusherin I. Izvestiye o rozhdenii i vospitanii i o zhizni svyateyshego Nikona patriarkha Moskovskogo i vseya Rossii [The news of the birth and upbringing and the life of His Holiness Patriarch Nikon of Moscow and All Russia]. Moscow, 1890.